1. Early Life and Background

Elmer Rice's early life in New York City and his initial foray into the legal profession profoundly influenced his later career as a playwright, shaping his keen observations of society and his commitment to social commentary.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Elmer Rice was born Elmer Leopold Reizenstein on September 28, 1892, at 127 East 90th Street in New York City. His family background included a strong influence from his grandfather, a political activist who had participated in the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states. After the failure of these upheavals, his grandfather emigrated to the United States and became a businessman. In his retirement, he lived with the Rice family and developed a close bond with young Elmer, instilling in him liberal and pacifist political views. A staunch atheist, his grandfather also influenced Rice's feelings about religion, leading him to refuse Hebrew school or a bar mitzvah. In contrast, Rice's relationship with his father was distant, with his grandfather and Uncle Will, who also boarded with the family, providing the affection his father withheld.

Growing up in the city's tenements, Rice spent much of his youth engrossed in reading, often to his family's dismay. He later reflected that "Nothing in my life has been more helpful than the simple act of joining the library." Due to his father's worsening epilepsy, Rice had to support his family, which led him to leave high school prematurely. He took on various menial jobs before independently preparing for state examinations to earn his diploma and gain admission to law school. Despite his dislike for legal studies, often reading plays during class, Rice graduated from New York Law School in 1912.

1.2. Early Career

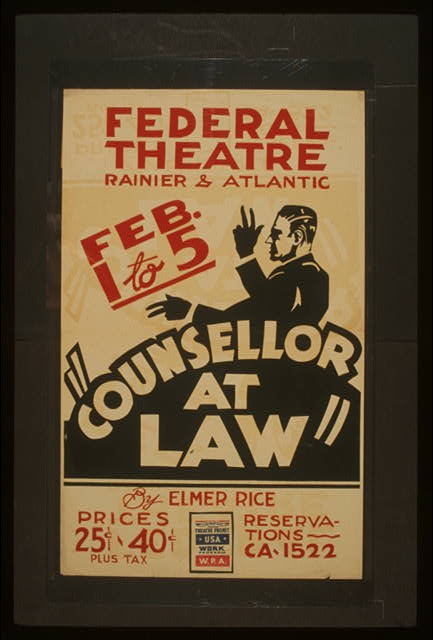

Rice embarked on a brief legal career after graduating from law school, but he left the profession in 1914. Despite his cynical outlook on lawyers, his two years in a law office provided him with rich material for several plays, most notably Counsellor-at-Law (1931), making courtroom dramas a specialty of his work.

Seeking a new livelihood, Rice decided to pursue full-time writing, a decision that quickly proved successful. His debut play, On Trial (1914), a melodramatic murder mystery co-authored with Frank Harris (not the biographer of Oscar Wilde), was a significant commercial hit. It ran for 365 performances in New York and was reportedly the first American drama to employ the innovative technique of reverse chronology, unfolding the story from its conclusion back to its beginning, a technique reminiscent of flashback in cinema. The play toured extensively across the United States with three separate companies and saw productions in numerous countries, including Argentina, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Mexico, Norway, Scotland, and South Africa. Rice earned 100.00 K USD from this first stage work, which he aptly titled "The Jackpot" in his memoirs, noting that none of his subsequent plays matched this financial success. On Trial was also adapted into a film three times, in 1917, 1928, and 1939.

During this period, Rice's attention also turned to political and social issues. World War I and Woodrow Wilson's conservatism solidified his criticism of the status quo. He had been converted to socialism in his teenage years through reading authors like George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, John Galsworthy, Maxim Gorky, Frank Norris, and Upton Sinclair. In the late 1910s, he frequented Greenwich Village, then a bohemian hub in New York City, befriending many socially conscious writers and activists, including the African-American poet James Weldon Johnson and illustrator Art Young.

2. Career and Major Works

Elmer Rice's career was marked by a prolific output of plays and other writings, characterized by his experimental spirit and his sharp social commentary, making him a significant figure in American theatre.

2.1. Playwriting

Rice's playwriting career spanned several decades, evolving through different styles and themes, consistently reflecting his engagement with contemporary society.

2.1.1. Early Successes

Following the commercial success of his debut, On Trial, Rice continued to explore diverse dramatic forms. While some of his subsequent early plays did not achieve the same distinction, he quickly established himself as an innovative voice in American theatre.

2.1.2. Expressionism and Realism

In 1923, Rice captivated audiences with his boldly expressionistic play, The Adding Machine, which he remarkably wrote in just 17 days. This satire critiqued the increasing regimentation of life in the machine age. The play follows the life, death, and bizarre afterlife of Mr. Zero, a dull bookkeeper who, as a mere cog in the corporate machine, murders his boss upon learning he is to be replaced by an adding machine. After his trial and execution, he enters the next life only to face similar issues, ultimately being deemed of minimal use even in heaven and sent back to Earth for recycling. Theatre critic Brooks Atkinson hailed it as "the most original and brilliant play any American had written up to that time... the harshest and most illuminating play about modern society [Broadway had ever seen]." Critics like Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woollcott were highly enthusiastic, with some hyperbolically comparing Rice to Henrik Ibsen. The play, directed by Philip Moeller, designed by Lee Simonson, and produced by the Theatre Guild, starred Dudley Digges (actor) and a young Edward G. Robinson. Ironically, despite its critical acclaim, the play earned its author no money. It was later adapted into an innovatively staged musical in 2007, enjoying a successful Off-Broadway run in 2008.

In 1924, Rice collaborated with Dorothy Parker on Close Harmony, a play loosely based on fellow Algonquin Round Table member Robert Benchley's marital problems. Despite good reviews, the play quickly closed.

Rice's second major hit and arguably his most enduring literary accomplishment was Street Scene (1929), originally titled Landscape with Figures. This play, later adapted into an opera by Kurt Weill, won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama for its realistic chronicle of life in the slums of New York. Atkinson described it as looking "like an improvisation" with "fifty characters casually strolling through it." The setting, based on the facade of a house at 25 West 65th Street, aimed to capture the "tone and humanity of a decaying brownstone." Despite being rejected by most producers and abandoned by director George Cukor during rehearsals as "un-stageable," Rice took over the direction himself, proving its stageworthiness. Like The Adding Machine, its break from conventional stage realism contributed to its appeal.

2.1.3. Later Plays

Rice's plays in the 1930s continued to explore social and legal themes. The Left Bank (1931) was a comedy about an expatriate's superficial attempt to escape American materialism in Paris. Counsellor-at-Law (1931) was a vigorous work that drew a realistic picture of the legal profession, based on Rice's own training, and remains one of his most frequently revived plays in regional theatres. During this decade, he also wrote two novels and had a lucrative period writing screenplays in Hollywood, though this time was marked by friction due to studio heads viewing him as one of "those Eastern Reds."

The Great Depression deeply influenced Rice, leading to the anti-capitalist play We, the People (1933). Rice described it as dealing with "the misfortunes of a typical skilled workman and his family, helplessly engulfed in the tide of national adversity." Despite an activist-minded cast and fifteen different sets designed by Aline Bernstein, the play failed amid what Rice called "agitated" reviews. A 1932 trip to the Soviet Union and Germany, where he heard Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels speak, provided material for subsequent plays. The Reichstag fire trial became an element in Judgement Day (1934), while conflicting American and Soviet ideologies formed the subject of the conversation-piece Between Two Worlds (1934).

After these plays, Rice returned to Broadway in 1937 to write and direct for the Playwrights' Company, which he helped establish alongside Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Sidney Howard, and Robert E. Sherwood. Of his later works, the most successful was the fantasy Dream Girl (1945), in which an overly imaginative girl encounters unexpected romance in reality. His final play was Cue for Passion (1958), a modern psycho-analytical variation of the Hamlet theme, featuring Diana Wynyard in a Gertrude-like role.

2.1.4. Stage Productions

Elmer Rice was a prolific playwright whose stage works include:

- A Defection from Grace with Frank Harris (1913, unpublished)

- The Seventh Commandment with Frank Harris (1913, unpublished)

- The Passing of Chow-Chow (1913, one act, published in 1925)

- On Trial (1914) with Frank Harris

- The Iron Cross (1917)

- The Home of the Free (1918)

- For the Defense (1919)

- It Is the Law (1922)

- The Adding Machine (1923)

- The Mongrel (1924) from a novel by Hermann Bahr

- Close Harmony (with Dorothy Parker, 1924)

- The Sidewalks of New York (1925, unpublished in 1925, published in 1934 as Three Plays Without Words)

- Is He Guilty? (1927)

- Wake Up, Jonathan with Hatcher Hughes (1928)

- The Gay White Way (1928)

- Cock Robin with Philip Barry (1929)

- Street Scene (1929, also directed)

- The Subway (1929)

- See Naples and Die (1930, also directed)

- The Left Bank (1931, also produced and directed)

- Counsellor-at-Law (1931, also produced and directed)

- The House in Blind Alley: A Play in Three Acts (1932)

- We, the People (1933, also produced and directed)

- Three Plays Without Words (1934, one act)

- Landscape with Figures

- Rus in Urbe

- Exterior

- The Home of the Free (1934, one act)

- Judgment Day (1934, also produced and directed)

- Two Plays (1935)

- Between Two Worlds (also produced and directed)

- Not for Children

- Black Sheep (1938, also produced and directed)

- American Landscape (1938, also directed)

- Two on an Island (1940, also directed)

- Flight to the West (1940, also directed)

- The Talley Method (1941, also produced and directed)

- A New Life (1944)

- Dream Girl (1946, also directed)

- The Grand Tour (1952, also directed)

- The Winner (1954, also directed)

- Cue for Passion (1959, also directed)

- Love Among the Ruins (1963)

- Court of Last Resort (1965)

2.2. Other Writings

Beyond his extensive work in theatre, Elmer Rice also contributed significantly to literature through his novels and non-fiction works, reflecting his diverse interests and critical perspectives.

2.2.1. Novels

Rice ventured into novel writing, often adapting his own plays or exploring themes relevant to his dramatic works. His novels include:

- On Trial (1915), a novelization of his successful play.

- Papa Looks for Something (unpublished, 1926).

- A Voyage to Purilia (1930), which was serialized in The New Yorker in 1929.

- Imperial City (1937).

- The Show Must Go On (1949).

2.2.2. Non-fiction and Autobiography

Rice was also a keen observer and critic of theatre and society, expressing his views through various non-fiction works and essays. His critical essays included "The Playwright as Director" (1929), "Organized Charity Turns Censor" (1931), "The Joys of Pessimism" (1931), "Sex in the Modern Theatre" (1932), "Theatre Alliance: A Cooperative Repertory Project" (1935), "The Supreme Freedom" (1949, pamphlet), "Conformity in the Arts" (1953, pamphlet), and "Entertainment in the Age of McCarthy" (1953). In his retirement, he authored The Living Theatre (1960), a controversial book on American drama, and his richly detailed autobiography, Minority Report (1964). He also contributed an essay titled "Author! Author!" to American Heritage in 1965.

2.2.3. Film Adaptations

Several of Elmer Rice's plays were adapted into films:

- 1917: On Trial

- 1922: For the Defense

- 1924: It Is the Law

- 1928: On Trial

- 1930: Oh Sailor Behave

- 1931: Street Scene

- 1933: Counsellor at Law

- 1939: On Trial

- 1948: Dream Girl

- 1969: The Adding Machine

2.3. Theatrical Activities

Elmer Rice's involvement in theatre extended beyond writing plays; he was also an active director, producer, and a key figure in establishing influential theatrical organizations.

2.3.1. Directing and Producing

Rice developed a strong interest in the practical aspects of theatre, often taking on the role of director for his own plays. He also became a theatre owner, acquiring the famed Belasco Theatre on Broadway. His hands-on approach to staging his works allowed him to maintain artistic control and realize his unique visions.

2.3.2. Founding of the Playwrights' Company

In 1937, Rice played a pivotal role in establishing the Playwrights' Company along with fellow notable playwrights Maxwell Anderson, S. N. Behrman, Sidney Howard, and Robert E. Sherwood. This collaborative venture aimed to provide a platform for playwrights to produce their own works with greater artistic independence, circumventing the commercial pressures of traditional Broadway producers.

2.3.3. Federal Theatre Project Involvement

Rice served as the first director of the New York office of the Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal program designed to employ theatre professionals during the Great Depression. However, he resigned from this position in 1936 to protest government censorship of the Project's "Living Newspaper" dramatization of Benito Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia. An outspoken defender of free speech, Rice left with a "blast of scorn" directed at the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration's attempts to control artistic expression, underscoring his unwavering commitment to artistic freedom and social conscience.

3. Philosophy and Social Activism

Elmer Rice was a deeply principled individual whose progressive political and social convictions were central to both his artistic output and his public life.

3.1. Political and Social Views

Rice was one of the more politically outspoken dramatists of his era. Influenced by early socialist thinkers, he adopted socialist leanings in his teens and maintained a critical perspective on the status quo. He was a pacifist and consistently expressed views against societal structures that he believed stifled human rights and perpetuated economic injustice. While he reluctantly supported the Communist Party candidate in the 1932 presidential election due to his dissatisfaction with both Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt's handling of the national crisis, he later became a supporter of Roosevelt in subsequent elections.

3.2. Activism and Public Stance

Rice actively championed civil liberties and free speech throughout his life. He was deeply involved with numerous organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Authors' League, the Dramatists Guild of America (where he was elected as the eighth president in 1939), and P.E.N. His principled resignation from the Federal Theatre Project in protest of censorship highlighted his unwavering commitment to artistic freedom. In the 1950s, he was also a vocal opponent of McCarthyism, speaking out against its repressive tactics and defending the rights of individuals against political persecution.

4. Personal Life

Beyond his public and professional roles, Elmer Rice's personal life was marked by family relationships and a profound appreciation for the arts.

4.1. Family and Relationships

Elmer Rice was married twice. In 1915, he married Hazel Levy, with whom he had two children, Margaret and Robert. After their divorce in 1942, he married actress Betty Field. They had three children together: John, Judy, and Paul. Field and Rice divorced in 1956.

4.2. Interests and Collections

Despite being born into a working-class family with no initial interest in the arts and primarily known for his dedication to theatre and politics, Rice developed a passionate appreciation for both Old Master and modern art. Over the years, he meticulously assembled an extensive art collection that included works by renowned artists such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Georges Rouault, Fernand Léger, André Derain, Paul Klee, and Amedeo Modigliani. He was a regular visitor to New York's museums, and in his autobiography, he recounted the powerful impact of Diego Velázquez's work during his first trip to Spain. In Mexico, he admired the art of Diego Rivera and the Mexican Muralists, artists whose political views he shared. Rice also maintained a close friendship with the Japanese-American modernist painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi.

5. Death

Elmer Rice resided for many years on a wooded estate in Stamford, Connecticut. He passed away on May 8, 1967, in Southampton, England, due to pneumonia following a heart attack. His obituaries widely acknowledged his long and respected career in theatre. Brooks Atkinson, in his history of Broadway, described Rice as "a plain, rather sober man with a reticent, unyielding personality...But when a social principle was at stake, he was more clear-headed than most people, and he was quietly invincible...He was one of Broadway's most eminent citizens."

6. Evaluation and Legacy

Elmer Rice left a complex and enduring legacy in American theatre and culture, marked by critical acclaim for his innovations and his unwavering commitment to social justice.

6.1. Critical Reception

Despite his significant commercial successes, Elmer Rice himself felt he had not achieved success as a writer in the way he wished to define it. While he earned a considerable amount of money, often by writing realistic dramas that were commercially viable, he felt this came at the cost of his more experimental vision. Plays like The Adding Machine and Street Scene, though critically acclaimed for their innovation, were anomalies in terms of financial return. His even more radical venture, The Sidewalks of New York (1925), an episodic play without words where "speech is indicated by gesture," was flatly rejected by the Theatre Guild. This reality-that Broadway was often not ready for the level of experimentation that truly inspired him-was a continuous source of frustration for Rice.

6.2. Criticism and Controversy

Rice's career was not without its share of controversies, particularly stemming from his outspoken political views and his critiques of societal norms. His book The Living Theatre (1960) sparked debate within the American drama community. His public stances against government censorship, as seen in his resignation from the Federal Theatre Project, and his opposition to McCarthyism, demonstrated his willingness to challenge authority and engage in public discourse, sometimes drawing criticism from those in power.

6.3. Influence and Impact

Elmer Rice's influence on American theatre is profound, primarily due to his pioneering use of dramatic techniques and his consistent integration of social commentary into his work. His play On Trial introduced the reverse chronology technique to the American stage, while The Adding Machine was a seminal work of American Expressionism, pushing the boundaries of theatrical form. Street Scene set a new standard for realism and naturalism, depicting urban life with unprecedented detail and a large, ensemble cast. Beyond his plays, Rice's active involvement in organizations like the Playwrights' Company and his principled stands against censorship and political repression underscored his enduring commitment to artistic freedom and social progress, influencing subsequent generations of playwrights and activists.

7. Archive

Elmer Rice's extensive papers were acquired by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin in 1968, a year after his death, with further additions made by family members over time. The collection, spanning over 100 boxes, provides a rich resource for researchers, including contracts, correspondence, manuscript drafts, notebooks, photographs, royalty statements, scripts, theatre programs, and more than 73 scrapbooks. The Ransom Center's library division also holds over 900 books from Rice's personal library, many of which contain his personal inscriptions or annotations.

8. Film Portrayal

Elmer Rice was portrayed by actor Jon Favreau in the 1994 film Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, which depicted the lives of members of the Algonquin Round Table.