1. Overview

David Dean Rusk (February 9, 1909 - December 20, 1994) was an American statesman who served as the United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. His tenure was the second-longest in the position's history, after Cordell Hull. Rusk played a pivotal role in shaping U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War, particularly his strong advocacy for U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

Prior to his appointment as Secretary of State, Rusk held various significant government roles, including a key position in the United States Department of State during the post-World War II era, where he was involved in the division of the Korean Peninsula at the 38th parallel north. He also served as the president of the Rockefeller Foundation. Throughout his career, Rusk was known for his unwavering loyalty to the presidents he served and his firm anti-communist stance, which heavily influenced his diplomatic decisions. His policies, especially concerning Vietnam, generated significant controversy and criticism, shaping his public image and historical legacy.

2. Early Life and Education

David Dean Rusk's formative years and academic pursuits laid the foundation for his distinguished career in public service, marked by a strong work ethic and an early immersion in international affairs.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

David Dean Rusk was born on February 9, 1909, in rural Cherokee County, Georgia. His ancestors had emigrated from Northern Ireland around 1795. His father, Robert Hugh Rusk (1868-1944), had attended Davidson College and Louisville Theological Seminary before leaving the ministry to become a cotton farmer and schoolteacher. His mother, Elizabeth Frances Clotfelter, was of Swiss descent and also a schoolteacher. When Rusk was four years old, his family relocated to Atlanta, where his father worked for the U.S. Post Office. The family struggled with poverty, which instilled in Rusk a stern Calvinist work ethic and morality. This experience also fostered his sympathy for Black Americans.

Like most white Southerners of his time, Rusk's family were Democrats, and young Rusk admired President Woodrow Wilson, the first Southern president since the American Civil War. At the age of nine, Rusk attended a rally in Atlanta where President Wilson advocated for the United States to join the League of Nations. Growing up amidst the mythology of the "Lost Cause" prevalent in the South, Rusk embraced a militaristic cultural outlook. In a high-school essay, he wrote that "young men should prepare themselves for service in case our country ever got into trouble." At 12, he joined the ROTC, taking his training duties very seriously. This intense reverence for the military persisted throughout his career, often leading him to accept the advice of generals.

2.2. Studies and Scholarships

Rusk received his early education in Atlanta's public schools, graduating from Boys High School in 1925. He then spent two years working for an Atlanta lawyer to save money for college. He attended Davidson College, a Presbyterian school in North Carolina, where he applied his Calvinist work ethic to his studies. He was an active member of the national military honor society Scabbard and Blade, rising to the rank of cadet lieutenant colonel commanding the ROTC battalion. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1931.

After Davidson, Rusk was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford University in England, where he studied international relations, earning an MA in Politics, Philosophy, and Economics (PPE). During his time at Oxford, he immersed himself in English history, politics, and popular culture, forming lifelong friendships within the British elite. He also studied for one semester in Germany, where he witnessed the rise of Nazism, which profoundly shaped his views. His experiences during the early 1930s, particularly witnessing Japan's seizure of Manchuria and the Oxford Union debate in 1933 where the motion "this house will not fight for king and country" was passed, further shaped his views. He later reflected that "one cannot have lived through those years and not have some pretty strong feelings... that it was the failure of the governments of the world to prevent aggression that made the catastrophe of World War II inevitable." Rusk's journey from poverty to Oxford solidified his passionate belief in the "American Dream" and his deep patriotism, convinced that anyone, regardless of their background, could achieve success in America.

Rusk taught at Mills College in Oakland, California, from 1934 to 1949, with an interruption for his military service. He also earned an LL.B. degree from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law in 1940.

3. Military Service and Early Career

Rusk's military service during World War II and his initial roles in public service provided him with foundational experiences in foreign affairs, particularly concerning East Asia and post-war international policy.

3.1. World War II Service

Rusk served in the Army reserves during the 1930s and was called to active duty in December 1940 as a captain. He served as a staff officer in the China Burma India Theater of World War II. During the war, Rusk authorized an air drop of arms to the Viet Minh guerrillas in Vietnam, who were commanded by Ho Chi Minh, his future adversary. By the war's end, he had achieved the rank of colonel and was decorated with the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster.

3.2. State Department Career (1945-1953)

After the war, Rusk briefly worked for the United States Department of War in Washington, D.C. before joining the United States Department of State in February 1945, where he worked for the Office of United Nations Affairs.

3.2.1. Korean Peninsula Division and UN Relations

In August 1945, Rusk played a significant role in the drafting of "General Order No. 1," the surrender document for Japanese forces. Specifically, he and Colonel Charles H. Bonesteel III proposed the division of the Korean Peninsula into American and Soviet spheres of influence at the 38th parallel north. This proposal was accepted by the Soviet Union, leading to the de facto division of Korea.

In February 1946, Rusk officially moved to the State Department. Following Alger Hiss's departure in January 1947, Rusk succeeded him as the director of the Office of Special Political Affairs (later the UN Bureau), a position he held until 1949. During this period, he was instrumental in the establishment of the Marshall Plan and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), demonstrating his commitment to post-war international cooperation and containment of communism. In 1948, Rusk supported Secretary of State George C. Marshall in advising President Harry S. Truman against recognizing Israel, fearing it would harm relations with oil-rich Arab states like Saudi Arabia. However, Truman, influenced by his legal counsel Clark Clifford, decided to recognize Israel. Rusk, who admired Marshall's loyalty to the President's ultimate authority in foreign policy, supported Marshall's decision and often quoted Truman's remark: "The president makes the foreign policy." In 1949, he was appointed Deputy Undersecretary of State under Dean Acheson, who had replaced Marshall.

3.2.2. Assistant Secretary for Far Eastern Affairs

In 1950, Rusk was appointed Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs at his own request, believing he had the most expertise in Asian affairs. He played an influential part in the U.S. decision to intervene in the Korean War. He also contributed to Japan's post-war compensation for victorious countries, as evidenced by the Rusk documents, and signed the Japan-US Administrative Agreement in Tokyo in 1952. Rusk was known as a cautious diplomat who consistently sought international support for U.S. policies. While he favored supporting Asian nationalist movements, arguing that European imperialism was unsustainable in Asia, the Atlanticist Acheson prioritized closer relations with European powers, which often precluded American support for Asian nationalism. Rusk, despite his personal leanings, dutifully supported Acheson's policy.

3.2.3. Korean War and East Asian Policy

Rusk's role in the Korean War was significant. When the war broke out on June 25, 1950, Rusk, as Assistant Secretary for Far Eastern Affairs, was immediately informed by W. Bradley Connors and instructed the U.S. Ambassador to Korea, John J. Muccio, to verify reports of the invasion.

Regarding French Indochina, Rusk advocated for U.S. support of the French government against the Communist Viet Minh guerrillas. He argued that the Viet Minh were merely instruments of Soviet expansionism in Asia and that refusing to support the French would amount to appeasement. Under strong American pressure, France granted nominal independence to the State of Vietnam in February 1950 under Bảo Đại, which the U.S. recognized within days. However, it was widely known that the State of Vietnam remained effectively a French colony. In June 1950, Rusk testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, stating that the conflict was "a civil war that has been in effect captured by the [Soviet] Politburo and... turned into a tool of the Politburo. So it isn't a civil war in the usual sense. It is part of the international war... We have to look at in terms of which side we are on in this particular kind of struggle... Because Ho Chi Minh is tied with the Politburo, our policy is to support Bao Dai and the French in Indochina until we have time to help them establish a going concern."

In April 1951, President Truman dismissed General Douglas MacArthur as commander of American forces in Korea over the issue of expanding the war into China. In May 1951, Rusk gave a speech at a dinner sponsored by the China Institute in Washington, implying that the U.S. should unify Korea under Syngman Rhee and overthrow Mao Zedong in China. This speech, which Rusk had not submitted to the State Department in advance, attracted significant attention, with columnist Walter Lippmann accusing Rusk of advocating for unconditional surrender in the Korean War. For embarrassing Acheson, Rusk was forced to resign from his position and moved to the private sector.

3.3. President of the Rockefeller Foundation

After leaving the State Department, Rusk and his family moved to Scarsdale, New York. He served as a Rockefeller Foundation trustee from 1950 to 1961. In 1952, he succeeded Chester I. Barnard as president of the foundation. During his eight-year tenure, he oversaw the foundation's philanthropic and developmental programs, particularly those focused on health, education, and economic development in underdeveloped and impoverished nations. During this time, he also became a formal member of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) and the Bilderberg Group, further solidifying his influence in international affairs. His reputation as a leading expert in foreign affairs continued to grow during this period.

4. Secretary of State

Dean Rusk's extensive tenure as Secretary of State under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson was defined by his deep involvement in U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War, most notably his steadfast commitment to the Vietnam War.

4.1. Kennedy Administration

Rusk's appointment as Secretary of State marked a new chapter in his career, where he navigated complex diplomatic challenges and established a working relationship with President Kennedy.

4.1.1. Nomination and Appointment as Secretary of State

On December 12, 1960, President-elect John F. Kennedy nominated Rusk to be Secretary of State. Rusk was not Kennedy's initial choice; his first preference, J. William Fulbright, proved too controversial due to his support for segregation. Rusk was described by David Halberstam as "everybody's number two" choice. Kennedy's interest was piqued by an article Rusk had recently written in Foreign Affairs titled "The President," which advocated for the president to direct foreign policy with the Secretary of State serving as a mere advisor.

Despite Kennedy's insistence, Rusk was not particularly eager for the position, as the annual salary for Secretary of State was 25.00 K USD, significantly less than the 60.00 K USD he earned as director of the Rockefeller Foundation. However, Rusk ultimately accepted the role out of a strong sense of patriotism. Kennedy biographer Robert Dallek noted that Kennedy, aiming to control foreign policy from the White House, chose Rusk as an "acceptable last choice" who would be a "faceless, faithful bureaucrat" rather than a leader. Kennedy often addressed him as "Mr. Rusk" rather than Dean, indicating a more formal and distant relationship.

Rusk took charge of a department that, despite being half its previous size, still employed 23.00 K people, including 6.00 K Foreign Service officers, and maintained diplomatic relations with 98 countries.

4.1.2. Major Foreign Policy Initiatives (Cuban Missile Crisis, etc.)

Rusk's tenure began with a faith in using military action to combat communism. Despite private misgivings about the Bay of Pigs Invasion, he remained noncommittal during executive council meetings and never openly opposed it. Early in his term, he harbored doubts about U.S. intervention in Vietnam, but he later became a staunch supporter. He often allied with the equally hawkish Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in debates within the Cabinet and the National Security Council.

In March 1961, Rusk expressed considerable frustration over the Laotian Civil War, noting reports that both sides paused combat for a ten-day water festival. Drawing on his World War II experience, he doubted that bombing alone would stop the Pathet Lao, emphasizing that bombing was only effective with ground troops to hold or advance territory. In April 1961, when a proposal to send 100 more American military advisors to South Vietnam (bringing the total to 800) came before Kennedy, Rusk argued for its acceptance, even though it violated the 1954 Geneva Accords, which limited foreign military personnel to 700. He suggested that the International Control Commission should not be informed and advisors be "placed in varied locations to avoid attention." While Rusk favored a hawkish approach to Laos, Kennedy decided against it due to the lack of modern airfields and the risk of Chinese intervention. Rusk opened the Geneva conference on neutralizing Laos but predicted its failure to Kennedy.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, Rusk strongly supported diplomatic efforts. A review of Kennedy's audio recordings of the EXCOMM meetings by Sheldon Stern, Head of the JFK Library, suggests that Rusk's contributions likely averted a nuclear war.

Rusk also continued his interest from the Rockefeller Foundation in aiding developing nations and supported low tariffs to encourage world trade.

4.1.3. Relationship with President Kennedy

As Rusk recounted in his autobiography, As I Saw It, his relationship with President Kennedy was not particularly strong. Kennedy was often irritated by Rusk's reticence in advisory sessions and felt that the State Department was "like a bowl of jelly" and "never comes up with any new ideas." In 1963, Newsweek ran a cover story on National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy titled "Cool Head for the Cold War," asserting that Bundy was "the real Secretary of State" and that Rusk "was not known for his force and decisiveness." Special Counsel to the President Ted Sorensen believed Kennedy acted as his own Secretary of State and often expressed impatience with Rusk, feeling he was under-prepared for emergency meetings. Rusk repeatedly offered his resignation, but it was never accepted.

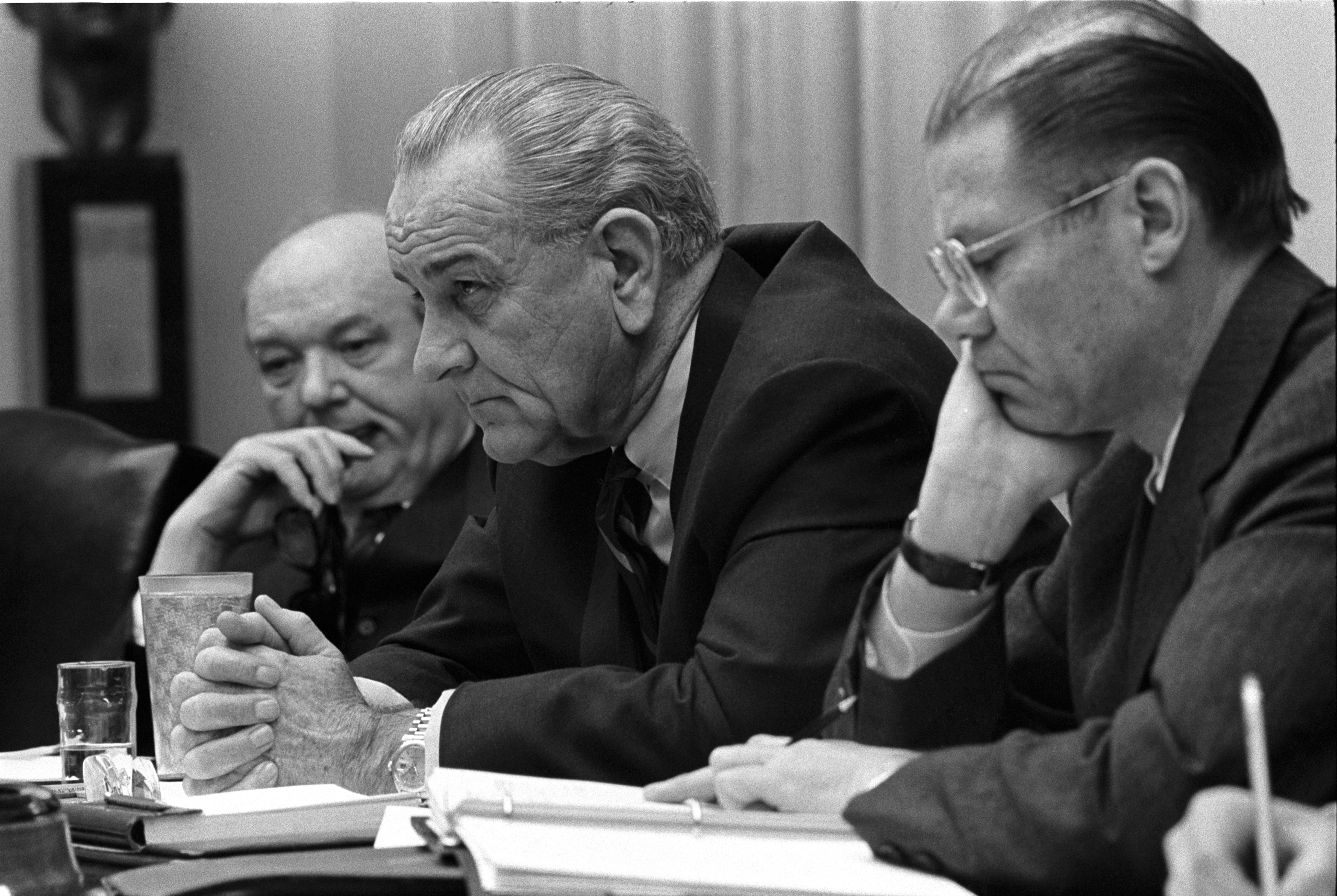

4.2. Johnson Administration

Rusk's role expanded significantly during President Johnson's administration, where he became a central figure in the Vietnam War policy and navigated various international incidents.

4.2.1. Vietnam War Policy

After Kennedy's assassination in November 1963, Rusk offered his resignation to the new President, Lyndon B. Johnson. However, Johnson, who appreciated Rusk's loyalty and steady demeanor, refused his resignation, and Rusk remained Secretary of State throughout Johnson's term. Rusk quickly became one of Johnson's favorite advisors.

Rusk became known as one of the Vietnam War's strongest supporters. In June 1964, Rusk met with Hervé Alphand, the French ambassador in Washington, to discuss a French plan for the neutralization of both Vietnams. Rusk was skeptical, telling Alphand: "To us, the defense of South Vietnam has the same significance as the defense of Berlin." He argued that the Berlin issue and the Vietnam War were part of the same global struggle against the Soviet Union, and the United States could not falter anywhere.

Just after the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964, Rusk supported the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. On August 29, 1964, during the presidential election campaign, Rusk called for bipartisan support for U.S. foreign policy and criticized Republican nominee Barry Goldwater for creating "mischief." In September, he stated that Goldwater's critiques "reflect a basic lack of understanding" of a U.S. President's handling of conflict.

On September 7, 1964, Rusk advised Johnson to exercise caution regarding military measures in Vietnam until diplomacy had been exhausted. However, he grew frustrated with the constant infighting among South Vietnam's junta of generals. After a failed coup against Nguyễn Khánh on September 14, Rusk messaged Ambassador Maxwell D. Taylor in Saigon, instructing him to "make it emphatically clear" to Khánh that Johnson was tired of the internal conflicts. Rusk emphasized that the U.S. had provided "massive assistance... in military equipment, economic resources, and personnel in order to subsidize continuing quarrels among South Vietnamese leaders." Reflecting Washington's general vexation with South Vietnam's political instability, Rusk argued to Johnson: "Somehow we must change the pace at which these people move, and I suspect that this can only be done with a pervasive intrusion of Americans into their affairs." Increasingly, the sentiment in Washington was that if South Vietnam could not defeat the Viet Cong guerrillas, the Americans would have to step in and win the war. On September 21, Rusk asserted that the U.S. would not be pushed out of the Gulf of Tonkin, and the continued presence of American forces would prevent it from becoming a "communist lake."

In September 1964, U.N. Secretary-General U Thant initiated a secret peace initiative in Burma, supported by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who pressured Ho Chi Minh to participate. U Thant reported to Rusk that Soviet pressure seemed effective, as China, North Vietnam's other arms supplier, could not match Soviet high-tech weaponry. However, Rusk did not press this information on Johnson, stating that participation in the talks would have signaled "the acceptance or the confirmation of aggression." The initiative ended when Khrushchev was ousted in October.

Following the Viet Cong attack on the American airbase at Bien Hoa on November 1, 1964, which killed four Americans, Rusk informed Ambassador Taylor that Johnson did not wish to act immediately due to the upcoming elections, but after the election, there would be "a more systematic campaign of military pressure on the North."

In May 1965, Rusk told Johnson that North Vietnam's "Four Points" peace terms were deceptive because the third point required "the imposition of the National Liberation Front on all South Vietnam." In June 1965, when General William Westmoreland requested 180.00 K troops for Vietnam, Rusk argued that the U.S. had to fight to maintain "the integrity of the U.S. commitment" worldwide. Despite some doubts about Westmoreland's assessment, Rusk warned the president in a rare memo that if South Vietnam were lost, "the Communist world would draw conclusions that would lead to our ruin and almost certainly to a catastrophic war." He also stated that the U.S. should have committed more heavily in 1961, believing that earlier troop deployment would have prevented current difficulties.

Rusk frequently clashed with his Undersecretary of State, George Ball, over Vietnam. When Ball argued that the South Vietnamese governing duo of Thieu and Ky were "clowns" unworthy of American support, Rusk retorted: "Don't give me that stuff. You don't understand that at the time of Korea we had to go out and dig up Syngman Rhee out of the bush where he was hiding. There was no government in Korea, either. We're going to get some breaks, and this thing is going to work." Rusk believed Ball's memos advocating for American withdrawal should be seen by as few people as possible and consistently argued against Ball in National Security Council meetings.

In 1964 and 1965, Rusk unsuccessfully requested British troops for Vietnam from Prime Minister Harold Wilson. Rusk, normally Anglophile, viewed the refusal as a "betrayal," reportedly telling the Times of London: "All we needed was just one regiment. The Black Watch would have done it. Just one regiment, but you wouldn't. Well, don't expect us to save you again. They can invade Sussex and we won't do a damn thing about it."

Shortly before his death, Ambassador to the UN Adlai Stevenson II mentioned in an interview the aborted peace terms in Rangoon in 1964, stating that U Thant was disappointed by Rusk's rejection. When questioned by Johnson, Rusk distinguished between "rejecting a proposal and not accepting it," claiming U Thant had missed the distinction.

In December 1965, when McNamara advised Johnson to pause the bombing of North Vietnam, Rusk estimated only a 1 in 20 chance that it would lead to peace talks. However, he supported the pause, arguing, "You must think about the morale of the American people if the other side keeps pushing. We must be able to say that all has been done." When Johnson announced the bombing pause on Christmas Day 1965, Rusk told the press, "We have put everything into the basket of peace except the surrender of South Vietnam." Some of the language in Rusk's peace offer, such as the demand that Hanoi publicly vow "to cease aggression" and the assertion that the bombing pause was "a step toward peace, although there has not been the slightest hint or suggestion from the other side as to what they would do if the bombing stopped," seemed designed to provoke rejection. On December 28, 1965, Rusk cabled Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in Saigon, presenting the bombing pause as a cynical public relations exercise: "The prospect of large-scale reinforcements in men and defense budget increases for the next eighteen-month period requires solid preparation of the American public. A crucial element will be a clear demonstration that we have explored fully every alternative but the aggressors has left us no choice." Rusk ordered Ambassador Henry A. Byroade in Rangoon to contact the North Vietnamese ambassador with an offer to extend the bombing pause if North Vietnam made "a serious contribution to peace." The offer was rejected, as North Vietnam refused peace talks until bombing ceased "unconditionally and for good," viewing the bombing as a violation of their sovereignty. In January 1966, Johnson ordered the Rolling Thunder bombing raids to resume.

In February 1966, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Fulbright, held televised hearings on the Vietnam War, featuring critics like George F. Kennan and General James M. Gavin. Rusk, serving as Johnson's principal spokesman on Vietnam, testified that the war was a morally justified struggle to halt "the steady extension of Communist power through force and threat." Historian Stanley Karnow described the hearings as compelling "political theater" as Fulbright and Rusk debated the war's merits.

By 1966, the Johnson administration was divided between "hawks" (like Rusk, Earle Wheeler, and Walt Whitman Rostow) and "doves" (like McNamara and W. Averell Harriman), with the latter favoring peace talks rather than withdrawal. Rusk equated withdrawal from Vietnam with "appeasement," though he sometimes advised Johnson to open peace talks to counter domestic criticism. On April 18, 1967, Rusk stated that the U.S. was prepared to "take steps to deescalate the conflict whenever we are assured that the north will take appropriate corresponding steps." In 1967, Rusk opposed Henry Kissinger's Operation Pennsylvania peace plan, remarking, "Eight months pregnant with peace and all of them hoping to win the Nobel Peace Prize." When Kissinger reported that North Vietnam would not begin peace talks without a bombing halt, Rusk advocated continuing the bombing, asking Johnson: "If the bombing isn't having that much effect, why do they want to stop the bombing so much?"

In October 1967, Rusk told Johnson he believed the March on the Pentagon was orchestrated by "the Communists" and pressed for an investigation. The subsequent investigation by various intelligence agencies found "no significant evidence that would prove Communist control or direction of the U.S. peace movement and its leaders," a report Rusk dismissed as "naive."

When Johnson first discussed not running for re-election in September 1967, Rusk opposed it, stating: "You must not go down. You are the Commander-in-chief, and we are in war. This would have a very serious effect on the country." By this time, many in the State Department were concerned by Rusk's drinking on the job, with William Bundy noting Rusk was like a "zombie" until he started to drink. McNamara was reportedly shocked to see Rusk drink an entire bottle of scotch in his office. However, Rusk's colleagues generally liked him, and none leaked their concerns to the media.

On January 5, 1968, Rusk sent notes to Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, seeking support to avoid recurrence of claimed bombing of Russian cargo ships in the Haiphong port. On February 9, Rusk was questioned by Senator William Fulbright regarding reports of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons introduction in South Vietnam.

The Tet Offensive in early 1968 shook Rusk and other Johnson administration members. During a news briefing, Rusk, typically courteous, snapped at a reporter asking how the administration was surprised: "Whose side are you on? Now, I'm the Secretary of State of the United States, and I'm on our side! None of your papers or your broadcasting apparatuses are worth a damn unless the United States succeeds. They are trivial compared to that question." Despite his anger at the media, he acknowledged public opinion was shifting against the war, recalling Georgians telling him: "Dean if you can't tell us when this war is going to end, well then maybe we just ought to chuck it." Rusk admitted, "The fact was that we could not, in any good faith, tell them." In March 1968, Rusk testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, chaired by Fulbright, who wore a necktie decorated with doves and olive branches. Though Rusk handled the questioning well, the televised hearings further damaged the Johnson administration's prestige. When Fulbright asked for a greater congressional say in the war, Rusk replied that Johnson would consult "appropriate members of Congress." When Senator Claiborne Pell questioned the war's worth, Rusk accused him of "moral myopia" regarding "the endless struggle for freedom."

On April 17, 1968, Rusk admitted the U.S. had taken "some lumps" propaganda-wise but urged persistence in finding a neutral location for peace talks. The next day, he added 10 sites to the initial five proposed, accusing Hanoi of engaging in a propaganda battle over neutral discussion areas.

Just before the Paris peace talks opened on May 13, 1968, Rusk advocated bombing North Vietnam north of the 20th parallel, a proposal strongly opposed by Defense Secretary Clark Clifford, who argued it would wreck the talks. Clifford persuaded a reluctant Johnson to adhere to his March 31 promise of no bombing north of the 20th parallel. Rusk continued his advocacy, telling Johnson on May 21, 1968: "We will not get a solution in Paris until we prove they can't win in the South." During a July 26, 1968, meeting, Rusk agreed with Richard Nixon's statement that bombing provided leverage in the Paris peace talks, saying: "If the North Vietnamese were not being bombed, they would have no incentive to do anything." When Nixon asked "Where was the war lost?", Rusk famously replied: "In the editorial rooms of this country."

In October 1968, Rusk opposed Johnson's consideration of a complete bombing halt to North Vietnam. On November 1, Rusk urged North Vietnam's long-term allies to pressure Hanoi to accelerate their involvement in the Paris peace talks.

4.2.2. Laos, Asian, and Middle Eastern Policy

Rusk continued to support aid to developing nations and low tariffs. In 1961, Rusk disapproved of the Indian invasion of Goa, which he viewed as an act of aggression against NATO ally Portugal, but was overruled by Kennedy, who sought to improve relations with India and noted Portugal's reliance on the U.S. for arms due to the Angolan rebellion. Regarding the West New Guinea dispute, Rusk favored supporting NATO ally the Netherlands against Indonesia, viewing Sukarno as pro-Chinese. Rusk accused Indonesia of aggression for attacking Dutch forces in New Guinea in 1962 and believed Sukarno violated the United Nations Charter, but Kennedy again overruled him. Kennedy prioritized improving relations with Indonesia, which he called "the most significant nation in Southeast Asia," fearing it might turn communist. Rusk later wrote he felt "queasy" about Kennedy's sacrifice of the Dutch to win over Indonesia and doubted the fairness of the "consultation" scheduled for 1969 to determine the territory's future.

In the Middle East, Rusk favored Saudi Arabia in the Arab Cold War against Nasser's Egypt, which was allied with the Soviet Union and sought a pan-Arab state. However, Rusk also argued to Kennedy and later Johnson that Nasser was a "spoiler" who played the Soviet Union against the U.S. for better bargains. Rusk noted that the U.S. had significant leverage over Egypt through the PL 480 law, which allowed the sale of surplus American agricultural production in local currency. Egypt, with its growing population and subsidized food prices, heavily relied on PL 480 food sales, a supply the Soviets could not match. Nasser promised to keep the Arab-Israeli dispute "in the icebox" in exchange for PL 480 sales. Rusk urged resisting congressional pressure to end PL 480 sales, arguing it would push Nasser closer to the Soviet Union and end the leverage maintaining peace between Egypt and Israel. When Nasser sent 70.00 K Egyptian troops into Yemen in September 1962 to support the republican government against Saudi-backed royalist guerrillas, Rusk approved increased arms sales to Saudi Arabia as indirect support for the royalists. On October 8, 1962, a "Food for Peace" deal was signed, committing the U.S. to sell 390.00 M USD worth of wheat to Egypt over three years. By 1962, Egypt imported 50% of its wheat from the U.S. through PL 480, amounting to 180.00 M USD annually, at a time when Egypt's foreign reserves were depleted by military spending.

In May 1963, angered by the quagmire in Yemen, Nasser ordered Egyptian Air Force squadrons to bomb towns in Saudi Arabia. With Egypt and Saudi Arabia on the brink of war, Kennedy, with Rusk's support, sided with Saudi Arabia, quietly dispatching U.S. Air Force squadrons and warning Nasser that an attack on Saudi Arabia would lead to war with Egypt. The warning had its effect. Despite tensions, Rusk continued to argue for maintaining PL 480 food sales to Egypt, believing it was crucial for U.S. leverage over Egypt and keeping the Arab-Israeli dispute "in the icebox."

4.2.3. Relationship with President Johnson

Rusk quickly became one of Johnson's favorite advisors. Just before the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Rusk and Johnson discussed Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who was seeking to be Johnson's running mate. Both agreed that Kennedy was "freakishly ambitious," with Rusk telling Johnson: "Mr. President, I just can't wrap my mind around that kind of ambition. I don't know how to understand it." Rusk's steadfastness, loyalty, and Southern background appealed to the Texas-born Johnson, leading to Rusk's increased visibility and influence during Johnson's presidency.

4.2.4. Major Diplomatic Incidents and Controversies (e.g., USS Liberty Incident)

Rusk drew the ire of supporters of Israel after he publicly stated his belief that the USS Liberty incident was a deliberate attack rather than an accident. He was outspoken: "Accordingly, there is every reason to believe that the USS Liberty was or should have been identified, or at least her nationality determined, prior to the attack. In these circumstances, the later military attack by Israeli aircraft on the USS Liberty is quite literally incomprehensible. As a minimum, the attack must be condemned as an act of military irresponsibility reflecting reckless disregard for human life. The subsequent attack by Israeli torpedo boats, substantially after the vessel was or should have been identified by Israeli military forces, manifests the same reckless disregard for human life. At the time of the attack, the USS Liberty was flying the American flag and its identification was clearly indicated in large white letters and numerals on its hull. It was broad daylight and the weather conditions were excellent. Experience demonstrates that both the flag and the identification number of the vessel were readily visible from the air. At a minimum, the attack must be condemned as an act of military recklessness reflecting wanton disregard for human life. The silhouette and conduct of the USS Liberty readily distinguished it from any vessel that could have been considered as hostile. The USS Liberty was peacefully engaged, posed no threat whatsoever to the torpedo boats, and obviously carried no armament affording it a combat capability. It could and should have been scrutinized visually at close range before torpedoes were fired." In 1990, he wrote: "I was never satisfied with the Israeli explanation. Their sustained attack to disable and sink Liberty precluded an assault by accident or by some trigger-happy local commander. Through diplomatic channels we refused to accept their explanations. I didn't believe them then, and I don't believe them to this day. The attack was outrageous." When an Israeli claim appeared in The Washington Post that they had inquired about U.S. ships in the area before the attack, Rusk telegraphed the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv, demanding "urgent confirmation." U.S. Ambassador to Israel Walworth Barbour confirmed Israel's story was false: "No request for info on U.S. ships operating off Sinai was made until after Liberty incident. Had Israelis made such an inquiry it would have been forwarded immediately to the chief of naval operations and other high naval commands and repeated to dept."

After President of France Charles de Gaulle withdrew France from the common NATO military command in February 1966 and ordered all American military forces to leave France, President Johnson asked Rusk to seek further clarification from President de Gaulle by asking whether the bodies of buried American soldiers must leave France as well. Rusk recorded in his autobiography that de Gaulle did not respond when asked, "Does your order include the bodies of American soldiers in France's cemeteries?"

On June 26, 1968, Rusk assured Berlin citizens that the United States, along with its NATO partners, was "determined" to secure Berlin's liberty and security, while criticizing East Germany's recent travel restrictions as violating "long standing agreements and practice." On September 30, Rusk met privately with Foreign Minister of Israel Abba Eban in New York City to discuss Middle East peace plans.

In the last days of the Johnson administration, the president wanted to nominate Rusk to the Supreme Court. Although Rusk had studied law, he did not have a law degree nor had he ever practiced law. Johnson argued that the Constitution did not require legal experience for Supreme Court service and claimed Senator Dick Russell would ensure his confirmation. However, Johnson failed to account for Senator James Eastland, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, who was a white supremacist and segregationist. Despite being a fellow Southerner, Eastland had not forgotten or forgiven Rusk for allowing his daughter to marry a Black man, and he announced he would block Rusk's nomination.

On January 2, 1969, Rusk met with five Jewish American leaders in his office to assure them that the U.S. had not changed its policy of recognizing Israel's sovereignty. One of the leaders, Irving Kane of the American-Israeli Public Affairs Committee, stated afterward that Rusk had successfully convinced him.

On December 1, 1968, citing the halt of bombing in North Vietnam, Rusk stated that the Soviet Union needed to come forward and contribute to advancing peace talks in Southeast Asia. On December 22, Rusk appeared on television to officially confirm the 82 surviving crew members of the USS Pueblo intelligence ship, speaking on behalf of the hospitalized President Johnson.

5. Retirement and Later Years

Rusk's post-government life included academic pursuits and reflections on his extensive career, marked by personal challenges and a reconciliation with his past.

5.1. Leaving Public Office and Return to Georgia

January 20, 1969, marked Rusk's last day as Secretary of State. Upon leaving the State Department, he delivered a brief valedictory: "Eight years ago, Mrs. Rusk and I came quietly. We wish now to leave quietly. Thank you very much." At a farewell dinner hosted by Anatoly Dobrynin, the longest-serving ambassador in Washington, Rusk told his host: "What's done cannot be undone." Dobrynin noted that Rusk driving away in a modest, barely working car seemed an apt symbolic end to the Johnson administration.

Upon his return to Georgia, Rusk suffered from a prolonged bout of depression and experienced psychosomatic illnesses, visiting doctors with complaints of chest and stomach pains that had no physical basis. Unable to work throughout 1969, he was supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, which paid him a salary as a "distinguished fellow."

5.2. Teaching Activities and Memoir

On July 27, 1969, Rusk voiced his support for the Richard Nixon administration's proposed anti-ballistic missile system, stating he would vote for it if he were a senator, with the understanding that further proposals would be reviewed if progress was made in Soviet Union peace talks. The same year, Rusk received both the Sylvanus Thayer Award and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, with Distinction.

Following his retirement, Rusk taught international law at the University of Georgia School of Law in Athens, Georgia from 1970 to 1984. Emotionally exhausted after eight years as Secretary of State, he narrowly survived a nervous breakdown in 1969. His appointment was initially challenged by Roy Harris, a university regent and Georgia campaign manager for George Wallace in 1968, who ostensibly argued, "We don't want the university to be a haven for broken-down politicians." In reality, Harris opposed Rusk due to his daughter's interracial marriage. However, Harris's vote was overruled, and Rusk's appointment proceeded. Rusk found the return to teaching emotionally satisfying, describing it as a "rejuvenation." Other professors remembered him as being like a "junior associate seeking tenure." Rusk later told his son that "the students I was privileged to teach helped rejuvenate my life and make a new start after those hard years in Washington."

In the 1970s, Rusk was a member of the Committee on the Present Danger, a hawkish group that opposed détente with the Soviet Union and was distrustful of nuclear arms control treaties. In 1973, Rusk eulogized Johnson when the former president lay in state.

In 1984, Rusk's son Richard, with whom he had not spoken since 1970 due to Richard's opposition to the Vietnam War, returned from Alaska to seek reconciliation. As part of this process, Rusk, who had become blind by then, agreed to dictate his memoirs to his son, which became the book As I Saw It.

In a review of As I Saw It, historian Warren Cohen noted that while the book downplayed the acrimony in Rusk's relations with McNamara and Bundy, it expressed considerable hostility towards Kennedy's closest advisor, his younger brother Robert, and U.N. Secretary-General U Thant. Rusk also expressed significant anger at the media's coverage of the Vietnam War, accusing anti-war journalists of "faking" stories and images. He spoke about what he called the "so-called freedom of the press," asserting that journalists from The New York Times and The Washington Post only wrote what their editors dictated, implying that true press freedom would have resulted in more positive war coverage. Despite his hawkish views on the Soviet Union, Rusk stated in his memoir that he never saw evidence of Soviet plans to invade Western Europe and "seriously doubted" they ever would. Cohen also observed that, in contrast to his years with Kennedy, Rusk was warmer and more protective towards Johnson, with whom he clearly had a better relationship.

Historian George C. Herring reviewed As I Saw It, finding it generally dull and uninformative regarding Rusk's time as Secretary of State, offering little new to historians. The most interesting and passionate parts, Herring noted, concerned Rusk's youth in the "Old South" and his conflict and reconciliation with his son Richard.

Rusk died of heart failure in Athens, Georgia, on December 20, 1994, at the age of 85. He and his wife are buried at the Oconee Hill Cemetery in Athens.

6. Assessment and Legacy

Dean Rusk's career is subject to varied historical assessments, acknowledging both his intellectual capabilities and his controversial policy decisions, particularly concerning the Vietnam War.

6.1. Historical Assessment

Historians generally agree that Rusk was a highly intelligent man, but also very shy and deeply immersed in the details and complexities of each case. This often made him reluctant to make decisive choices and hindered his ability to clearly explain government policies to the media. Jonathan Coleman notes that Rusk was deeply involved in the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, NATO, and the Vietnam War. He was typically cautious on most issues, with the notable exception of Vietnam. Coleman summarizes that Rusk "established only a distant relationship with President Kennedy but worked more closely with President Johnson. Both presidents appreciated his loyalty and his low-key style. Although an indefatigable worker, Rusk exhibited little talent as a manager of the Department of State."

Regarding Vietnam, historians concur that President Johnson heavily relied on the advice of Rusk, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy. Their consensus was that a communist takeover of all of Vietnam was unacceptable, and the only way to prevent it was to escalate America's commitment. Johnson adopted their conclusions, often rejecting dissenting views.

Rusk's son, Richard, reflected on his father's time as Secretary of State: "With this reticent, reserved, self-contained, emotionally bound-up father of mine from rural Georgia, how could the decision making have gone any differently? His taciturn qualities, which served him so well in negotiating with the Russians, ill-prepared him for the wrenching, introspective, soul-shattering journey that a true reappraisal of Vietnam policy would have involved. Although trained for high office, he was unprepared for such a journey, for admitting that thousands of American lives, and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, might have been lost in vain."

George Herring, writing in 1992, described Rusk as "a man utterly without pretense, a thoroughly decent individual, a man of stern countenance and unbending principles. He is a man with a passion for secrecy. He is a shy and reticent man, who as Secretary of State sipped scotch to loosen his tongue for press conferences. Stolid and normally laconic, he also has a keen, dry wit. He has often been described as the 'perfect number two,' a loyal subordinate who had strong-if unexpressed-reservations about the Bay of Pigs operation, but after its failure could defend it as though he had planned it."

Smith Simpson, summarizing the views of historians and political scientists, stated: "Here was a man who had much going for him but failed in crucial respects. A decent, intelligent, well-educated man of broad experience in world affairs who, early in life, evidenced qualities of leadership, seemed diffidently to hold back rather than to lead as secretary of state, seeming to behave, in important ways, like a sleeve-plucking follower of presidents rather than their wise and persuasive counselor."

6.2. Positive Contributions

Rusk's positive contributions include his unwavering dedication to public service and his steadfast loyalty to the presidents he served. His low-key style and commitment to the U.S. mission abroad were appreciated by both Kennedy and Johnson. He played a significant role in shaping U.S. foreign policy during a critical era of the Cold War, contributing to the development of key alliances and strategies for containing communism, such as his involvement in the establishment of NATO and his diplomatic efforts during the Cuban Missile Crisis, which are credited with helping to avert a nuclear war.

6.3. Criticisms and Controversies

Rusk's career was marked by significant criticisms and controversies, predominantly stemming from his role in the Vietnam War and certain aspects of his personal and public life.

6.3.2. Personal and Political Controversies

Beyond his policy decisions, Rusk faced personal and political controversies. In 1967, he considered resigning when it became known that his daughter, Peggy, planned to marry Guy Smith, a Black classmate from Stanford University. Rusk believed that as a Southerner working for a Southern president, such a marriage, if he did not resign or stop it, would bring immense criticism upon both him and the president. The Richmond News Leader publicly stated that the wedding was offensive and that "anything which diminishes [Rusk's] personal acceptability is an affair of state." However, after discussions with McNamara and President Johnson, he decided not to resign. A year after the wedding, when Rusk was invited to teach at the University of Georgia Law School, his appointment was denounced by Roy Harris, a university regent and ally of Alabama Governor George Wallace, ostensibly because "We don't want the university to be a haven for broken-down politicians," but in reality due to his opposition to Peggy Rusk's interracial marriage.

Rusk's relationship with the media also became contentious. He accused anti-war journalists of "faking" stories and images that portrayed the war negatively. He expressed frustration with what he called the "so-called freedom of the press," arguing that if there were true freedom, major newspapers would have presented the war more positively. During a news briefing at the height of the Tet Offensive, he famously snapped at a reporter: "Whose side are you on? Now, I'm the Secretary of State of the United States, and I'm on our side! None of your papers or your broadcasting apparatuses are worth a damn unless the United States succeeds. They are trivial compared to that question." He later attributed the war's public perception as being "lost... in the editorial rooms of this country."

Concerns about Rusk's drinking on the job also arose in the later years of the Johnson administration, though his colleagues kept these private due to their affection for him. Furthermore, his strong belief that the anti-war movement was controlled by "the Communists," despite intelligence investigations finding no significant evidence, highlighted his rigid anti-communist worldview. The opposition of Senator James Eastland, a white supremacist, to Rusk's potential Supreme Court nomination due to his daughter's marriage, further underscored the personal controversies that intersected with his public life.

7. Personal Life

Dean Rusk's private life was marked by his family relationships and personal experiences, which at times intersected with his public career.

7.1. Family Relationships

David Dean Rusk married Virginia Foisie (October 5, 1915 - February 24, 1996) on June 9, 1937. They had three children: David, Richard, and Peggy Rusk.

7.2. Relationships with Family

Rusk's strong support for the Vietnam War caused considerable strain within his family, particularly with his son Richard, who was opposed to the war. Despite his personal opposition, Richard enlisted in the Marine Corps and avoided anti-war demonstrations out of love for his father. This psychological strain contributed to Richard suffering a nervous breakdown and led to a break in their relationship that lasted for years. However, in 1984, Richard returned to Georgia from Alaska to seek reconciliation. As part of this process, Rusk, who had become blind, dictated his memoirs to Richard, resulting in the book As I Saw It.

Another significant aspect of Rusk's family life that drew public scrutiny was his daughter Peggy's interracial marriage to Guy Smith in 1967. This event caused considerable controversy, particularly in the South, and led Rusk to consider resigning from his position as Secretary of State to avoid imposing a "political burden on the president." The public reaction, including condemnation from some Southern media outlets, highlighted the societal tensions of the era. Despite the scrutiny, Rusk ultimately decided against resigning after consulting with his colleagues, and the marriage proceeded. The controversy resurfaced when Rusk returned to Georgia, with a university regent attempting to block his faculty appointment due to his daughter's marriage.

8. In Popular Culture

David Dean Rusk has been represented in popular culture, particularly in Marvel Comics. The comics feature a fictionalized version of Dean Rusk named "Dell Rusk," a corrupt politician who is later revealed to be an alter-ego of the supervillain Red Skull. This connection is foreshadowed by "Dell Rusk" being an anagram of "Red Skull." The character of Dell Rusk also appears in the video game Marvel: Avengers Alliance, where he is depicted as a member of the World Security Council that controls S.H.I.E.L.D.. In this iteration, Dell Rusk appears to be a distinct character rather than a disguise used by Red Skull.

Secretary Rusk has also been portrayed in several dramatizations of historical events:

- Actor Larry Gates portrayed Secretary Rusk in the 1974 ABC television docudrama The Missiles of October, which dramatized the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962.

- Actor Henry Strozier played Secretary Rusk in another dramatization of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the 2000 theatrical film Thirteen Days, directed by Roger Donaldson.

- Actor John Aylward played Secretary Rusk in the 2002 biographical television film Path to War, directed by John Frankenheimer.

9. Publications and Awards

David Dean Rusk authored significant written works, including his memoir, and received major honors for his public service.

His publications include:

- "U.S. Foreign Policy: A Discussion with Former Secretaries of State Dean Rusk, William P. Rogers, Cyrus R. Vance, and Alexander M. Haig, Jr." in International Studies Notes, Vol. 11, No. 1, Special Edition: The Secretaries of State, Fall 1984.

- Winds of Freedom-Selections from the Speeches and Statements of Secretary of State Dean Rusk, January 1961 - August 1962 (1963), co-authored with Ernest K. Lindley.

- As I Saw It: Dean Rusk as told to Richard Rusk (1990), his memoir dictated to his son.

Rusk received several notable awards and honors:

- Cecil Peace Prize in 1933.

- Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster for his military service during World War II.

- Sylvanus Thayer Award in 1969.

- Presidential Medal of Freedom, with Distinction, in 1969.

Several institutions and places have been named in his honor:

- Rusk Eating House, the first women's eating house at Davidson College, founded in 1977.

- The Dean Rusk International Studies Program at Davidson College.

- Dean Rusk Middle School in Canton, Georgia.

- Dean Rusk Hall on the campus of the University of Georgia.