1. Overview

Suriname, officially the Republic of Suriname, is a country located on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north, French Guiana to the east, Guyana to the west, and Brazil to the south. With an area of approximately 63 K mile2 (163.82 K km2), it is the smallest sovereign state in South America. Paramaribo is the country's capital and largest city, home to roughly half of its population of approximately 618,000 people. Suriname's society is one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse in the world, a legacy of Dutch colonization which brought peoples from Africa, India, Java (Indonesia), and China, alongside the indigenous populations.

Historically, Suriname was inhabited by various indigenous groups before European colonization began in the 16th century. The Dutch consolidated control by the late 17th century, establishing a profitable plantation economy based on sugar, coffee, and cocoa, fueled by the brutal institution of African slavery. Following the abolition of slavery in 1863, indentured laborers were brought from Asia. Suriname gained independence from the Netherlands on November 25, 1975. The post-independence period was marked by political instability, including a military coup in 1980 led by Dési Bouterse, a civil war, and significant human rights concerns. The 21st century has seen efforts towards democratic consolidation and economic development, though challenges related to governance, social equity, and reliance on natural resource extraction (primarily gold, bauxite, and oil) persist. Over 90% of Suriname's land area is covered by rainforest, contributing to its status as a carbon-negative country and highlighting the importance of environmental conservation and sustainable development for the welfare of its people and the protection of its rich biodiversity. The country's political system is a constitutional republic and representative democracy. Dutch is the official language, reflecting its colonial heritage, though Sranan Tongo, an English-based creole, and numerous other languages are widely spoken.

2. Etymology

The name Suriname is believed to derive from an indigenous Taino (Arawak) group called the SurinenSurinenUncoded languages, who inhabited the region at the time of European contact. The suffix -ame, common in Surinamese river and place names such as the Coppename River, may originate from aimariver or creek mouthArapaho or eimariver or creek mouthArapaho in Lokono, an Arawak language spoken in the country.

The earliest European records provide variations of "Suriname" as the name of the Suriname River, upon which colonies were eventually established. Lawrence Kemys, in his "Relation of the Second Voyage to Guiana" (1596), mentioned passing a river called "ShurinamaShurinamaEnglish". In 1598, a fleet of three Dutch ships visiting the Wild Coast noted passing the river "SurinamoSurinamoDutch". By 1617, a Dutch notary spelled the name of the river, where a Dutch trading post had existed three years prior, as "SurrenantSurrenantDutch".

British settlers, who founded the first European colony at Marshall's Creek along the Suriname River in 1630, spelled the name "SurinamSurinamEnglish". This spelling remained the standard in English for a long period. The Dutch navigator David Pietersz. de Vries wrote of traveling up the "SernameSernameDutch" river in 1634 until he encountered the English colony. The terminal vowel persisted in future Dutch spellings and pronunciations. A 1640 Spanish manuscript titled "General Description of All His Majesty's Dominions in America" referred to the river as SoronamaSoronamaSpanish. In 1653, instructions for a British fleet sailing to meet Lord Willoughby in Barbados, then the seat of English colonial government in the region, again used the spelling "SurinamSurinamEnglish". A 1663 royal charter stated the region around the river was "called Serrinam also Surrinam".

As a result of the "SurrinamSurrinamEnglish" spelling, 19th-century British sources proposed the folk etymology "SurryhamSurryhamEnglish", claiming it was the name given to the Suriname River by Lord Willoughby in the 1660s in honor of the Duke of Norfolk and Earl of Surrey when an English colony was established under a grant from King Charles II. This folk etymology was repeated in later English-language sources.

When the territory was taken over by the Dutch, it became part of a group of colonies known as Dutch Guiana. The official English spelling of the country's name was changed from "Surinam" to "Suriname" in January 1978. However, "Surinam" can still be found in English, for instance, in the name of Surinam Airways and the Surinam toad. The older English name is reflected in the English pronunciation. In Dutch, the official language of Suriname, the pronunciation has the main stress on the third syllable and a terminal schwa sound.

3. History

The history of Suriname is characterized by the presence of indigenous cultures, European colonization, a plantation economy reliant on enslaved labor, subsequent waves of indentured servitude, and a complex journey to independence followed by periods of political upheaval and efforts towards democratic consolidation.

3.1. Pre-colonial period

Indigenous settlement in the area now known as Suriname dates back as early as 3,000 BC. The earliest inhabitants were various indigenous peoples, whose societies and cultures were intricately adapted to the diverse ecosystems of the region. Among the largest tribes were the Arawak (or Lokono), a nomadic coastal tribe that sustained themselves through hunting and fishing. They were among the first known inhabitants of the area.

Later, the Carib (or Kali'na) migrated to the region and, using their superior sailing ships, conquered the Arawak in many areas. The Carib established settlements, such as Galibi (Kupali Yumïtree of the forefathersGalibi Carib) at the mouth of the Marowijne River. While the larger Arawak and Carib tribes predominantly lived along the coast and savannas, smaller indigenous groups inhabited the inland rainforests. These included peoples such as the Akurio, Trió, Warao, and Wayana. These communities developed distinct languages, social structures, and spiritual beliefs, living in relative isolation until the arrival of Europeans. The pre-colonial period was marked by inter-tribal relations, trade, and occasional conflict, shaping the human landscape of the Guianas long before European intervention.

3.2. Colonial period

Beginning in the 16th century, European powers, including Spain, France, and England, explored the Guiana coast. Alonzo de Ojeda and Juan de la Cosa, sailing for Spain, charted parts of the coast around 1499. In the 17th century, Dutch and English settlers established the first significant European plantation colonies along the fertile river plains. The earliest documented colony in Guiana was an English settlement named Marshall's Creek along the Suriname River, founded around 1630. This was followed by another short-lived English colony, Surinam, from 1650 to 1667.

Persistent disputes arose between the Dutch and the English for control of this territory. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch captured Surinam. In the Treaty of Breda (1667), the Dutch decided to keep the nascent plantation colony of Surinam, while in return, the English retained New Amsterdam (the main city of the former colony of New Netherland in North America), which they renamed New York.

In 1683, the Society of Suriname was founded by the city of Amsterdam, the Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck family, and the Dutch West India Company. This society was chartered to manage and defend the colony. The colonial economy became heavily reliant on African slaves to cultivate, harvest, and process commodity crops such as coffee, cocoa, sugar cane, and cotton on plantations along the rivers. The treatment of enslaved people by planters was notoriously brutal, even by the standards of the time. Historian C. R. Boxer wrote that "man's inhumanity to man just about reached its limits in Surinam." This extreme brutality led many enslaved Africans to escape the plantations.

With the help of indigenous South Americans living in the adjoining rainforests, these runaway slaves, known as Maroons (Dutch: Marrons; French: Nèg'Marrons), established new, unique, and resilient communities in the interior. The Maroons gradually developed several independent tribes through a process of ethnogenesis, as they comprised individuals from various African ethnicities. These tribes include the Saramaka, Paramaka, Ndyuka (or Aukan), Kwinti, Aluku (or Boni), and Matawai. The Maroons often raided plantations to recruit new members, capture women, and acquire weapons, food, and supplies, sometimes resulting in the death of planters and their families. Colonists built defenses, and mounted armed campaigns against the Maroons, who generally evaded capture by retreating into the rainforest, which they knew intimately. To end hostilities, in the 18th century, the European colonial authorities signed several peace treaties with different Maroon tribes, granting them sovereign status and trade rights in their inland territories, effectively acknowledging their autonomy.

In November 1795, the Society of Suriname was nationalized by the Batavian Republic. From then on, the Batavian Republic and its legal successors (the Kingdom of Holland and the Kingdom of the Netherlands) governed the territory as a national colony, barring two periods of British occupation: between 1799 and 1802, and between 1804 and 1816.

3.3. Abolition of slavery and labor migration

The Netherlands abolished slavery in Suriname on July 1, 1863. However, the system involved a gradual process that required formerly enslaved people to work on plantations for a 10-year transition period for minimal pay, which was presented as partial compensation for their former enslavers. This transition period expired in 1873. Following full emancipation, most freedmen largely abandoned the plantations where they had toiled for generations, preferring to move to the capital city, Paramaribo. Some were able to purchase the plantations they had worked on, particularly in the districts of Para and Coronie, and their descendants continue to live on these lands. In some instances, plantation owners, to evade debts owed to the formerly enslaved workers for the ten years of labor post-1863, paid them with property rights to parts of the plantation.

As a plantation colony, Suriname's economy was heavily dependent on labor-intensive commodity crops. The abolition of slavery created a severe labor shortage. To address this, the Dutch colonial government recruited and transported contract or indentured laborers from various parts of the world. Large numbers came from British India (modern-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh), through an arrangement with the British. Another significant group of indentured laborers came from the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), primarily from the island of Java. Additionally, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, smaller numbers of laborers, mostly men, were recruited from China and the Middle East.

This complex history of colonization, enslavement, and large-scale labor migration resulted in Suriname becoming one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse countries in the world, a characteristic that profoundly shapes its society, politics, and cultural expressions today. The conditions faced by indentured laborers were often harsh, and their arrival introduced new social dynamics and cultural influences that continue to define Suriname.

3.4. Path to independence

During World War II, on November 23, 1941, under an agreement with the Dutch government-in-exile, the United States sent approximately 2,000 soldiers to Suriname to protect the bauxite mines, which were crucial for the Allied war effort in producing aluminum for aircraft. In 1942, the Dutch government-in-exile began to review the future relationship between the Netherlands and its colonies in the post-war period.

In 1954, Suriname became a constituent country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, alongside the Netherlands Antilles and the Netherlands itself. Under this arrangement, known as the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Suriname gained autonomy in internal affairs, while the Netherlands retained control over defense and foreign policy. This marked a significant step towards self-governance.

In 1973, the local government, led by the National Party of Suriname (NPS), whose membership was largely Creole (ethnically African or mixed African-European), initiated negotiations with the Dutch government for full independence. This move towards independence was, in part, supported by the then left-wing Dutch government led by Prime Minister Joop den Uyl. After a period of negotiations, Suriname was granted full independence on November 25, 1975. Unlike Indonesia's earlier war for independence from the Netherlands, Suriname's path to sovereignty was achieved through peaceful political processes. However, the prospect of independence also led to concerns among some segments of the population, resulting in significant emigration to the Netherlands. For the first decade following independence, a large part of Suriname's economy was sustained by foreign aid provided by the Dutch government.

3.5. Post-independence and military rule

Suriname became independent on November 25, 1975, with Johan Ferrier, the former governor, as its first President and Henck Arron, leader of the National Party of Suriname (NPS), as Prime Minister. The years leading up to and immediately following independence saw nearly one-third of the population emigrate to the Netherlands, concerned about the new country's future. Surinamese politics soon became characterized by ethnic polarization and corruption, with the NPS accused of using Dutch aid money for partisan purposes and electoral fraud in the 1977 elections.

On February 25, 1980, a military coup led by a group of 16 sergeants, prominently featuring Dési Bouterse, overthrew Arron's government. This event ushered in a period of military rule and political instability. Opponents of the military regime attempted several counter-coups in April 1980, August 1980, March 1981, and March 1982, all of which failed. One leader of a counter-attempt, Wilfred Hawker, was summarily executed after capture.

A particularly dark chapter was the December murders on December 7-9, 1982, when 15 prominent citizens-journalists, lawyers, and union leaders who had criticized the military dictatorship-were arrested, taken to Fort Zeelandia in Paramaribo, and executed by Bouterse's regime. This event led to international condemnation and the suspension of development aid from the Netherlands and the United States, severely impacting Suriname's economy.

From 1986, the country was embroiled in the Surinamese Interior War, a brutal civil conflict between the national army and Maroons led by Ronnie Brunswijk, Bouterse's former bodyguard, who formed the "Jungle Commando". The war caused significant loss of life, displacement (with over 10,000 Surinamese, mostly Maroons, fleeing to French Guiana), and further devastation to the economy and social fabric. Human rights abuses were widespread during this period.

Under domestic and international pressure, national elections were held in 1987, and a new constitution was adopted, though Bouterse remained head of the army. Dissatisfied with the civilian government, Bouterse dismissed the ministers in 1990 via telephone, an event popularly known as the "Telephone Coup." His direct power began to wane after the 1991 elections, which brought Ronald Venetiaan to the presidency. Efforts were made to restore democratic institutions and end the Interior War, with a peace accord signed in 1992. However, the legacy of military rule, human rights violations, and economic hardship cast a long shadow over Suriname.

3.6. 21st century

The 21st century in Suriname has been marked by continued efforts toward democratic consolidation, significant economic challenges, and the enduring political influence of figures from its turbulent past. In 1999, Dési Bouterse was convicted in absentia in the Netherlands for drug trafficking. Despite this, he returned to power democratically, being elected President of Suriname by the National Assembly in July 2010 and re-elected in 2015. His presidency was controversial, particularly due to an amnesty law passed in 2012 that sought to shield him and others from prosecution for their roles in the December murders. However, in November 2019, a Surinamese court convicted Bouterse for his part in the 1982 killings and sentenced him to 20 years in prison. He remained in office during the appeal process.

The 2020 general election resulted in a victory for an opposition coalition, and Chan Santokhi of the Progressive Reform Party (VHP) was elected President. His inauguration took place on July 16, 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Santokhi's government faced significant economic difficulties, including high national debt inherited from the previous administration and the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic.

In February 2023, Paramaribo witnessed significant protests against the rising cost of living, inflation, and austerity measures implemented by the Santokhi government. Some protesters stormed the National Assembly building, demanding the government's resignation. The government condemned the violence but acknowledged the economic hardships faced by the population.

Dési Bouterse died on December 24, 2023, while a fugitive following his conviction for the December murders. His death marked the end of an era for a figure who had dominated Surinamese politics for over four decades, leaving a complex legacy of authoritarian rule, human rights abuses, and popular support among certain segments of the population. The nation continues to grapple with issues of economic stability, social justice, strengthening democratic institutions, and addressing the legacies of past conflicts and human rights violations.

4. Geography

Suriname is characterized by its extensive rainforest cover, numerous rivers, and a relatively narrow coastal plain where most of its population resides. The country's geography plays a significant role in its biodiversity, resource distribution, and settlement patterns.

4.1. Topography and borders

Suriname is the smallest independent country in South America, with a total area of approximately 63 K mile2 (163.82 K km2). Situated on the Guiana Shield, it lies mostly between latitudes 1° and 6°N, and longitudes 54° and 58°W. The country can be divided into two main geographic regions. The northern, lowland coastal area, roughly above a line from Albina through Paranam to Wageningen, has been cultivated and is where the majority of the population lives. This region features fertile plains and swampy areas. The southern part, constituting about 80% of Suriname's land surface, consists of dense tropical rainforest and sparsely inhabited savanna along the border with Brazil.

The two main mountain ranges are the Bakhuys Mountains and the Van Asch Van Wijck Mountains. Julianatop is the highest mountain in the country at 4.2 K ft (1.29 K m) above sea level. Other notable mountains include Tafelberg (3.4 K ft (1.03 K m)), Mount Kasikasima (2356 ft (718 m)), Goliathberg (1175 ft (358 m)), and Voltzberg (787 ft (240 m)).

Suriname is crisscrossed by numerous rivers, many of which flow northward to the Atlantic Ocean. Major rivers include the Suriname River (after which the country is named), the Marowijne River (forming the border with French Guiana), the Courantyne River (forming the border with Guyana), the Coppename River, and the Saramacca River. The Brokopondo Reservoir, created by the Afobaka Dam on the Suriname River, is one of the largest artificial lakes in the world.

Suriname is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north, French Guiana to the east, Guyana to the west, and Brazil to the south. Suriname has longstanding territorial disputes with both Guyana and French Guiana. The dispute with Guyana concerns the Tigri Area (known in Guyana as the New River Triangle), a jungle area of about 6.0 K mile2 (15.60 K km2) between the Upper Corentyne (or New River) and the Coeroeni and Kutari rivers, which Suriname claims as its own based on the historical interpretation of the Courantyne River's main source. The border with French Guiana along the Marowijne River (Maroni) is also disputed in its southern section, concerning which tributary constitutes the main headwater. A portion of the disputed maritime boundary with Guyana was arbitrated by the Permanent Court of Arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on September 20, 2007, which largely favored Guyana's claims but also granted Suriname a significant portion of the contested area. From Suriname's perspective, which exercises de facto control over established areas, these border regions remain points of contention.

4.2. Climate

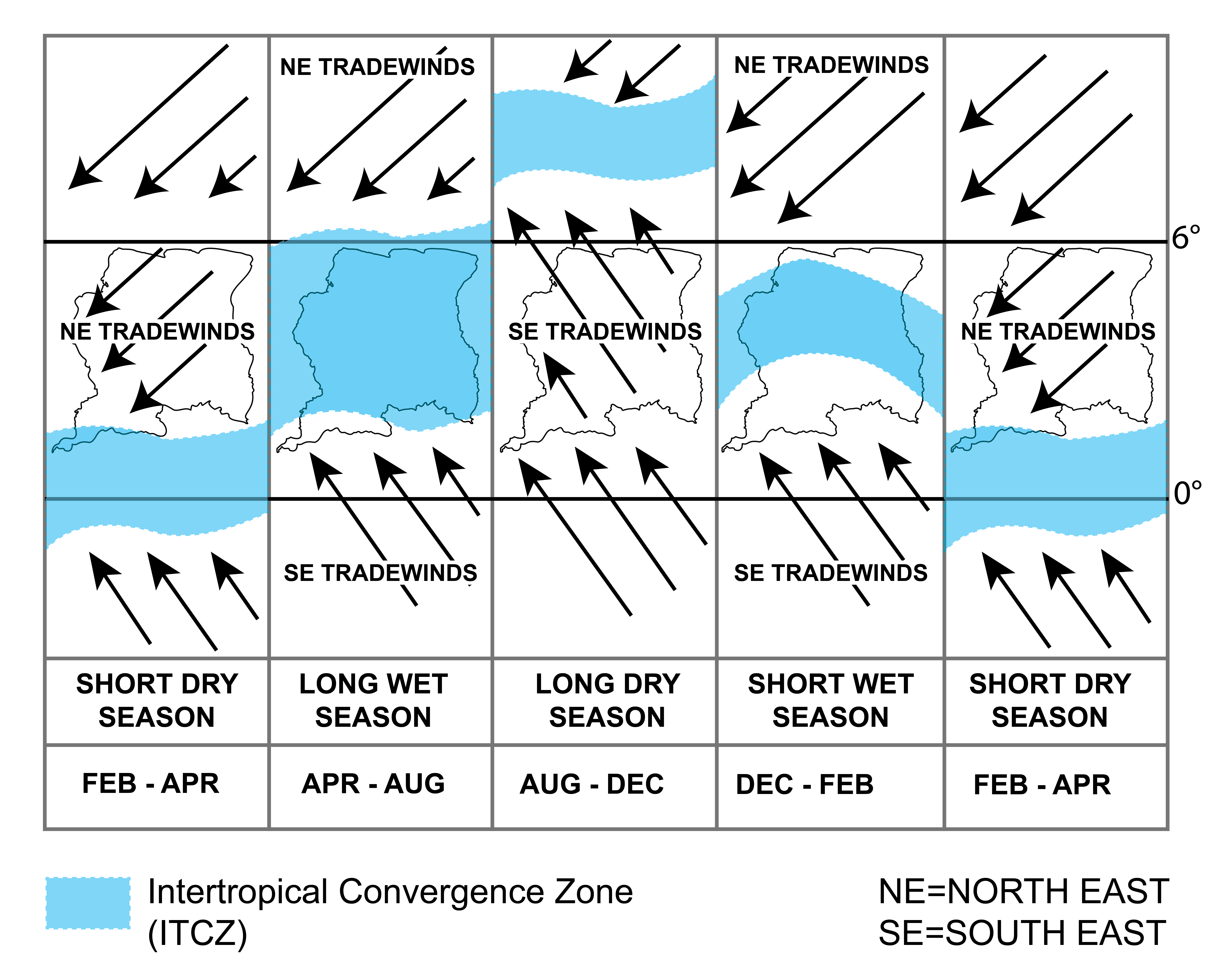

Lying two to five degrees north of the equator, Suriname has a hot and wet tropical climate, with temperatures that do not vary significantly throughout the year. The average relative humidity is high, generally between 80% and 90%. The average daily temperature ranges from 84.2 °F (29 °C) to 93.2 °F (34 °C). Due to the high humidity, the perceived temperature can often feel up to 11 °F (6 °C) hotter than the recorded air temperature.

The year in Suriname is characterized by two wet seasons and two dry seasons. The main wet season typically runs from April to August, and a shorter wet season occurs from November to February. The main dry season is from August to November, with a shorter dry season from February to April. Annual rainfall varies, with the coastal region receiving around 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm) and the interior up to 0.1 K in (3.00 K mm).

Climate change is an emerging concern, with potential impacts including rising temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns, and more extreme weather events, which could affect agriculture, biodiversity, and coastal communities. Despite being a relatively poor country with limited contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions, Suriname's extensive forest cover has allowed it to maintain a carbon-negative economy since at least 2014, absorbing more carbon dioxide than it emits.

4.3. Biodiversity and conservation

Suriname boasts exceptional biodiversity due to its vast, largely untouched rainforests, varied habitats, and tropical climate. Over 90% of the country is covered by forest, the highest proportion of forest cover of any nation in the world. This extensive forest is part of the larger Amazon rainforest ecosystem and the Guiana Shield, one of the world's most biodiverse regions.

The country's flora is incredibly rich, with thousands of plant species, including numerous types of trees, orchids, and medicinal plants. Snakewood (Brosimum guianense) is a notable native tree, prized for its dense, patterned wood, which is sometimes illegally exported. The fauna is equally diverse, encompassing hundreds of species of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Iconic Amazonian species found in Suriname include jaguars, tapirs, giant otters, harpy eagles, anacondas, and caimans. The country is also home to numerous primate species, colorful birds like macaws and toucans, and a vast array of insects. The blue poison dart frog (Dendrobates tinctorius "azureus") is endemic to the southern Sipaliwini region. Coastal areas, particularly near Galibi, are important nesting grounds for several species of sea turtles, including the leatherback sea turtle.

In October 2013, an expedition of international scientists researching ecosystems in Suriname's Upper Palumeu River Watershed cataloged 1,378 species, discovering 60 that were potentially new to science, including six frog species, one snake species, and eleven fish species.

Suriname has made significant efforts towards environmental conservation. The Central Suriname Nature Reserve, established in 1998, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site covering 6.2 K mile2 (16.00 K km2) of primary tropical forest. It is one of the largest protected areas in South America and is recognized for its pristine condition and high biodiversity. Other major national parks and protected areas include the Galibi Nature Reserve, Brownsberg Nature Park, Eilerts de Haan Nature Park, and the Sipaliwani Nature Reserve. In total, about 16% of Suriname's land area consists of national parks and other protected areas.

Indigenous communities, such as the Trio and Wayana, are increasingly active in conservation. In 2015, they presented a declaration for an indigenous conservation corridor spanning 28 K mile2 (72.00 K km2) in southern Suriname, an area vital for climate resilience and freshwater security. Suriname's commitment to conservation is also reflected in its participation in international initiatives like REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation). The country's vast forests play a crucial role in its carbon-negative status, contributing significantly to global climate change mitigation efforts. However, threats to biodiversity persist from gold mining (especially illegal small-scale operations that use mercury), logging, and agricultural expansion, necessitating ongoing vigilance and sustainable resource management practices.

5. Politics

Suriname is a constitutional republic and representative democracy based on the Constitution of 1987. The political system involves a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, though its history has seen periods of military intervention that disrupted democratic governance. The system aims to balance the representation of Suriname's diverse ethnic population.

5.1. Government

The legislative branch of government is the National Assembly (De Nationale AssembléeDe Nationale Assemblée (DNA)Dutch), a 51-member unicameral parliament. Members are elected for a five-year term through a system of proportional representation from the country's electoral districts. The National Assembly's functions include passing laws, approving the national budget, and electing the President and Vice President.

The executive branch is led by the President, who is the head of state and head of government. The President is elected for a five-year term by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly. If no candidate achieves this majority after two rounds of voting, a United People's Assembly (Verenigde VolksvergaderingUnited People's AssemblyDutch) is convened, consisting of all National Assembly members plus regional and municipal representatives elected in the most recent national election. This larger body then elects the President by a simple majority. The President appoints a cabinet of ministers, typically around sixteen, to manage various government departments. The Vice President is elected concurrently with the President by the National Assembly or People's Assembly and assists the President, also serving as Prime Minister in chairing the Council of Ministers. There is no constitutional provision for the removal or replacement of the president, except in the case of resignation.

The judiciary is headed by the High Court of Justice (Hof van JustitieCourt of JusticeDutch), which is the supreme court. This court supervises the magistrate courts. Members of the High Court are appointed for life by the President in consultation with the National Assembly, the State Advisory Council, and the National Order of Private Attorneys. The judiciary is constitutionally independent, though its effectiveness can be influenced by political and economic pressures. The establishment of a Constitutional Court (Constitutioneel HofConstitutional CourtDutch) to review the constitutionality of laws has been a long-discussed reform, with the court officially installed in 2020.

Historically, Surinamese politics has been characterized by coalition governments formed by various ethnic-based political parties. The stability of these coalitions and the overall governance have been challenged by periods of military rule (notably in the 1980s) and economic difficulties. Efforts to strengthen democratic institutions, combat corruption, and ensure human rights are ongoing themes in Surinamese politics.

5.2. Administrative divisions

Suriname is divided into ten administrative districts (districtendistrictsDutch). Each district is headed by a District Commissioner (districtscommissarisdistrict commissionerDutch), who is appointed and can be dismissed by the President. The districts vary widely in size and population density, with the coastal districts being much more populous than the vast, sparsely inhabited Sipaliwini district in the interior.

The ten districts of Suriname are:

| # | District | Capital | Area (km2) | Area (%) | Population (2012 census) | Population (%) | Pop. dens. (inhabitants/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brokopondo | Brokopondo | 7,364 | 4.5 | 15,909 | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| 2 | Commewijne | Nieuw-Amsterdam | 2,353 | 1.4 | 31,420 | 5.8 | 13.4 |

| 3 | Coronie | Totness | 3,902 | 2.4 | 3,391 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 4 | Marowijne | Albina | 4,627 | 2.8 | 18,294 | 3.4 | 4.0 |

| 5 | Nickerie | Nieuw Nickerie | 5,353 | 3.3 | 34,233 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

| 6 | Para | Onverwacht | 5,393 | 3.3 | 24,700 | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| 7 | Paramaribo | Paramaribo | 182 | 0.1 | 240,924 | 44.5 | 1323.8 |

| 8 | Saramacca | Groningen | 3,636 | 2.2 | 17,480 | 3.2 | 4.8 |

| 9 | Sipaliwini | None (administration centered in Paramaribo) | 130,567 | 79.7 | 37,065 | 6.8 | 0.3 |

| 10 | Wanica | Lelydorp | 443 | 0.3 | 118,222 | 21.8 | 266.9 |

| SURINAME | Paramaribo | 163,820 | 100.0 | 541,638 | 100.0 | 3.3 |

The districts are further subdivided into 62 resorts (ressortenresortsDutch). Resorts serve as a secondary administrative level, particularly for electoral and statistical purposes, and their councils play a role in local governance and community development.

5.3. Foreign relations

Suriname's foreign policy is shaped by its history, geographic location, economic needs, and commitment to regional and international cooperation. It maintains diplomatic relations with numerous countries and is a member of several international and regional organizations.

A cornerstone of Suriname's foreign relations has historically been its "special relationship" with the Netherlands, its former colonial ruler. This relationship has encompassed significant development aid, cultural ties, and a large Surinamese diaspora in the Netherlands. However, relations were severely strained during the military rule of Dési Bouterse, particularly after the December murders in 1982 and Bouterse's subsequent conviction for drug trafficking in the Netherlands in 1999. Aid was suspended, and diplomatic contacts were limited. Relations improved following the return to democratic governance and particularly after Chan Santokhi became president in 2020, with both countries expressing a desire to normalize and strengthen ties.

The United States is another important partner. Relations have generally been positive since 1991, with cooperation in areas such as security through the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI), health via the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and military funding from the U.S. Department of Defense.

Suriname is an active member of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), playing a role in regional integration, trade, and functional cooperation. It also participates in the Organization of American States (OAS), and the United Nations (UN) and its specialized agencies. Suriname has been a member of The Forum of Small States (FOSS) since its founding in 1992. As a country with significant Muslim and Hindu populations, Suriname is also a member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

Relations with the European Union (EU) are conducted bilaterally and through regional frameworks like EU-CELAC and EU-CARIFORUM dialogues. Suriname is a party to the Cotonou Agreement (now succeeded by the Samoa Agreement), which governs relations between the EU and the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States.

In recent years, Suriname has intensified South-South cooperation. It has deepened ties with China, which has funded and undertaken large-scale infrastructure projects, including port rehabilitation and road construction. Brazil, its southern neighbor, is a key partner in areas such as education, health, agriculture, and energy. Relations with Indonesia are also significant, given the large Javanese-Surinamese population; cultural exchanges and economic cooperation are areas of focus, and a sister city agreement exists between Yogyakarta and the Commewijne District.

Suriname also maintains bilateral relations with neighboring Guyana and French Guiana, though these are sometimes complicated by unresolved territorial disputes. Cooperation on issues like cross-border crime, environmental protection, and economic development is pursued.

The country generally advocates for multilateralism, sustainable development, respect for international law, and the particular vulnerabilities of small developing states. Its foreign policy aims to attract investment, secure development assistance, and promote peace and stability, with an increasing emphasis on partnerships that support human rights and democratic values.

5.4. Military

The Armed Forces of Suriname, known as the Nationaal LegerNational ArmyDutch (NL), are responsible for the defense of the nation's territory, sovereignty, and constitutional order. The NL consists of three branches: the Army, the Air Force, and the Navy (including a Coast Guard component). The President of the Republic is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces (Opperbevelhebber van de StrijdkrachtenSupreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed ForcesDutch). The President is assisted by the Minister of Defence. Beneath the President and Minister of Defence is the Commander of the Armed Forces (Bevelhebber van de StrijdkrachtenCommander of the Armed ForcesDutch), to whom the military branches and regional military commands report.

The origins of the Surinamese military lie in the Royal Netherlands Army's Troepenmacht in SurinameForces in SurinameDutch (TRIS), which was responsible for the defense of Suriname during the colonial era. Upon independence in 1975, this force was transformed into the Surinaamse KrijgsmachtSurinamese Armed ForcesDutch (SKM). Following the 1980 military coup, the SKM was rebranded as the Nationaal Leger (NL).

The Surinamese military has played a significant and often controversial role in the country's post-independence history. It was the main actor in the 1980 coup and the subsequent military dictatorship under Dési Bouterse. During the 1980s, the military was also heavily involved in the Surinamese Interior War (1986-1992) against the Jungle Commando led by Ronnie Brunswijk. This period was marked by serious human rights abuses committed by military forces.

After the return to democratic rule in the late 1980s and early 1990s, efforts were made to depoliticize the military and subject it to civilian control. The military's current functions include border security, disaster relief, assistance to civil authorities, and participation in international peacekeeping operations (e.g., a contingent served in Haiti). The NL is relatively small, with an estimated total active personnel of around 2,000-2,500. It has received training and material support from countries such as the Netherlands, the United States, Brazil, and more recently, China and India. In 1965, during the Dutch colonial era, the Coronie site in Suriname was used by the Dutch and Americans for multiple Nike Apache sounding rocket launches.

Challenges for the military include limited resources, modernization needs, and combating illegal activities such as illicit gold mining and drug trafficking, particularly in the vast and difficult-to-patrol interior regions. The military's role in upholding democratic principles and human rights remains a critical aspect of its ongoing development.

6. Economy

Suriname's economy has historically been reliant on the export of natural resources, particularly bauxite, gold, and oil. Agriculture and fisheries also contribute, but the economy is vulnerable to fluctuations in global commodity prices. Efforts towards diversification and sustainable development are ongoing, alongside challenges of managing debt and promoting social equity.

6.1. Main sectors

The mining sector has long been the backbone of Suriname's economy. Bauxite was historically dominant, with mining operations primarily run by Alcoa subsidiary Suralco. For decades, alumina (processed bauxite) accounted for a large share of GDP and export earnings. However, Alcoa ceased its bauxite operations in Suriname in 2015 due to depleted high-grade reserves and other economic factors, marking the end of a significant era.

Gold has since become the leading mineral export. Both large-scale industrial mining (e.g., Rosebel mine, formerly operated by Iamgold and now by Zijin Mining, and Merian mine, operated by Newmont) and extensive, often informal and illegal, small-scale gold mining (SSGM) operations contribute significantly to production. Gold exports constitute a substantial portion of total export earnings (often 60-80%) and contribute significantly to GDP (around 8.5% in 2021). The gold production in 2015 was reported at 30 metric tonnes. Small-scale mining, while economically important for many, raises serious concerns about deforestation, mercury pollution, and labor practices.

Oil is another key sector. The state-owned oil company, Staatsolie, is responsible for exploration, drilling, refining, and marketing of petroleum products. Onshore production has been ongoing for decades, and recent offshore discoveries have generated considerable optimism for future production growth, potentially transforming the economy. In 2022, Staatsolie reported revenues of 840.00 M USD and contributed 320.00 M USD to the state treasury. In 2023, revenues were 722.00 M USD with a contribution of 335.00 M USD to the treasury. The oil sector contributes around 10% to GDP.

The agricultural sector remains important, particularly for domestic food supply and some exports. Key agricultural products include rice (especially in the Nickerie district), bananas, palm kernels, coconuts, peanuts, citrus fruits, and various vegetables. The fishing industry, particularly shrimp harvesting, also contributes to exports. Forestry and timber production are other components, though sustainable practices are crucial given Suriname's vast rainforest cover.

Tourism, especially ecotourism focused on the country's rainforests and cultural heritage, is an emerging sector with significant potential for growth.

6.2. Trade and investment

Suriname's economy is highly dependent on international trade. Major export products include gold, oil, alumina (historically), lumber, shrimp, fish, rice, and bananas. Key export destinations in 2012 included the United States (26.1%), Belgium (17.6%), the United Arab Emirates (12.1%), Canada (10.4%), Guyana (6.5%), France (5.6%), and Barbados (4.7%). More recent data indicates Switzerland and China have also become significant export markets, especially for gold.

Major import products include capital equipment, petroleum products (for domestic consumption beyond local refining capacity), foodstuffs, cotton, and consumer goods. In 2012, primary import suppliers were the United States (25.8%), the Netherlands (15.8%), China (9.8%), the UAE (7.9%), Antigua and Barbuda (7.3%), Netherlands Antilles (5.4%), and Japan (4.2%).

The investment climate in Suriname has faced challenges due to political instability in the past, bureaucratic hurdles, and concerns about governance. Attracting foreign direct investment, particularly in sectors beyond mining, is a key government priority. The long time required to register a new business (reportedly 694 days in some past analyses) has been cited as a deterrent to investment.

6.3. Economic challenges and outlook

Suriname has faced significant economic challenges, including high inflation, fiscal deficits, substantial public debt, and a strong reliance on volatile commodity prices. The cessation of Alcoa's bauxite operations in 2015 dealt a blow to the economy. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated economic difficulties, leading to a sharp contraction in GDP and increased poverty.

Past governments have struggled with fiscal discipline. For example, the Wijdenbosch government in the late 1990s ended a structural adjustment program, leading to falling tax revenues, frozen Dutch development funds, and high inflation due to monetary expansion to cover fiscal deficits (estimated at 11% of GDP in 1999).

Current economic data (based on EN source's 2010 estimates, which are dated but provide a snapshot):

- GDP (2010 est.): 4.79 B USD

- Annual growth rate real GDP (2010 est.): 3.5%

- Per capita GDP (2010 est.): 9.90 K USD

- Inflation (2007): 6.4%

The economic outlook is heavily tied to the development of offshore oil reserves, which could provide a significant boost to government revenues and foreign exchange earnings. However, managing this potential wealth sustainably, ensuring equitable distribution of benefits, avoiding the "Dutch disease," and promoting diversification remain critical challenges. Addressing fiscal imbalances, strengthening governance, improving the business climate, and investing in human capital are essential for achieving sustainable economic growth and enhancing social equity. The high cost of living and inflation led to significant social protests in February 2023, underscoring the urgent need for effective economic management that addresses the welfare of the population, especially vulnerable groups.

7. Demographics

Suriname's population is relatively small but remarkably diverse, a direct consequence of its colonial history involving the forced migration of enslaved Africans and the subsequent recruitment of indentured laborers from Asia, alongside its indigenous inhabitants. Most of the population lives in the narrow northern coastal plain, particularly in and around the capital, Paramaribo.

7.1. Ethnic groups

Suriname is characterized by its multicultural society, with no single ethnic group forming a majority. The ethnic composition, according to 2012 census data and more recent estimates, is as follows:

{| class="wikitable"

! Ethnic group !! Approximate Percentage

|-

| Indo-Surinamese (descendants of indentured laborers from British India, primarily from regions like Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Bengal) || 27.4%

|-

| Maroons (descendants of escaped African slaves who formed independent communities in the interior; major groups include Ndyuka/Aucans, Saramaccans, Paramaccans, Kwinti, [[Aluku people|Aluku]/Boni, and Matawai) || 21.7%

|-

| Creoles (people of mixed African and European, primarily Dutch, descent) || 15.7%

|-

| Javanese (descendants of indentured laborers from the island of Java, then part of the Dutch East Indies) || 13.7%

|-

| Mixed heritage (individuals identifying with multiple ethnic backgrounds) || 13.4%

|-

| Indigenous Peoples (Amerindians; main groups include Akurio, Arawak/Lokono, Kalina/Caribs, Tiriyó, and Wayana, living mainly in Paramaribo, Wanica, Para, Marowijne, and Sipaliwini districts) || 3.8%

|-

| Chinese (descendants of 19th-century indentured workers and more recent migrants) || 1.5%

|-

| Europeans (primarily descendants of Dutch 19th-century immigrant farmers known as "Boeroes", and other European groups like the Portuguese; many left after independence) || 0.3%

|-

| Other (including Lebanese, primarily Maronites; Jews of Sephardic and Ashkenazi origin, historically centered in Jodensavanne; and recent migrants like Brazilians and Haitians, many involved in gold mining, often without legal status) || 2.5%

|}

Inter-ethnic relations are generally peaceful, though ethnic identity often plays a role in politics and social organization. The cultural contributions of each group are integral to Suriname's national identity.

7.2. Languages

[[File:194d9866ea4_8f8e19cc.jpg|width=2112px|height=2816px|thumb|left|upright|A butcher in the Central Market in Paramaribo, with signs written in Dutch, the official language.]]

[[File:194d986728f_86f636a8.jpg|width=5344px|height=3008px|thumb|right|A poetry sign in Sranan Tongo located in Rotterdam, Netherlands, reflecting the linguistic heritage of the Surinamese diaspora.]]

Suriname has a rich linguistic landscape with roughly 14 local languages spoken, but Dutch is the sole official language. It is used in education, government, business, and the media. Over 60% of the population speak Dutch as a native language, and many others speak it as a second language. In 2004, Suriname became an associate member of the Dutch Language Union (Taalunie). Suriname is the only sovereign nation outside Europe where Dutch is the official and prevailing language spoken by a majority. Surinamese Dutch is recognized as a distinct national dialect.

Sranan Tongo, an English-based creole language, is the most widely used vernacular language in daily life and commerce, serving as a lingua franca among different ethnic groups. It is often used interchangeably with Dutch, depending on the social context, with Dutch generally considered the prestige dialect.

Sarnami Hindustani (a koiné language based on Bhojpuri and Awadhi) is the third-most used language, spoken primarily by the Indo-Surinamese community.

The six Maroon languages are also English-based creoles and include Saramaccan, Ndyuka (Aukan), Aluku, Paramaccan, Matawai, and Kwinti. Aluku, Paramaccan, and Kwinti are largely mutually intelligible with Ndyuka, as is Matawai with Saramaccan.

Surinamese-Javanese is spoken by descendants of Javanese indentured laborers.

Amerindian languages include Akurio, Arawak-Lokono, Carib-Kari'nja, Sikiana-Kashuyana, Tiro-Tiriyó, Waiwai, Warao, and Wayana.

Chinese languages such as Hakka, Cantonese, and Hokkien are spoken by descendants of Chinese indentured laborers, while Mandarin is common among recent Chinese immigrants.

Near the borders with neighboring countries, languages such as English, Guyanese Creole, Portuguese, Spanish, French, and French Guianese Creole are also spoken due to migration. This linguistic diversity reflects the complex history and multicultural makeup of Suriname.

7.3. Religion

[[File:194d98656d9_a9a11f2e.jpg|width=5472px|height=3648px|thumb|left|The Neveh Shalom Synagogue (left) and the Keizerstraat Mosque (right) standing adjacently in Paramaribo, a symbol of religious tolerance and coexistence.]]

[[File:194d98666fe_dd903c2f.jpg|width=4032px|height=2268px|thumb|right|The Arya Diwaker Hindu temple in Paramaribo, a prominent center for the Hindu community.]]

Suriname's religious landscape is as diverse as its ethnic makeup, characterized by a high degree of religious freedom and interfaith harmony. Religious tolerance is a notable feature of Surinamese society. A famous example of this is the close proximity of the Neveh Shalom Synagogue and the Keizerstraat Mosque in Paramaribo, which are located next to each other and have been known to share facilities.

[[File:194d9866139_8d579df4.jpg|width=800px|height=627px|thumb|left|The Church of the Sacred Heart (Heilig Hartkerk) in Paramaribo, an example of Christian religious architecture.]]

Based on the 2012 census and 2020 estimates, the religious composition is approximately as follows:

{| class="wikitable"

! Religion !! Approximate Percentage (2012/2020 data)

|-

| Christianity (Total) || ~48.4% - 52.3%

|-

| Protestant (including Pentecostalism 11.18%, Moravian Church 11.16%, Reformed 0.7%, and other denominations 4.4%) || ~25.6% - 26.7%

|-

| Catholic || ~21.6%

|-

| Other Christian || ~1.2%

|-

| Hinduism (primarily among the Indo-Surinamese population) || ~18.8% - 22.3%

|-

| Islam (largely among Javanese and some Indo-Surinamese) || ~13.9% - 14.3%

|-

| Folk Religions (Total) || ~1.8% - 5.6%

|-

| Winti (an Afro-Surinamese religion, practiced mainly by those of Maroon ancestry) || ~1.8%

|-

| Kejawèn (Javanism, a syncretic faith among some Javanese Surinamese) || ~0.8%

|-

| Indigenous folk traditions || (Often incorporated into larger religions)

|-

| No Religion / Unaffiliated || ~5.4% - 7.5%

|-

| Other Religions (including Buddhism, Judaism) || ~2.1%

|-

| Not Stated || ~3.2%

|}

Suriname has one of the largest proportional Hindu and Muslim populations in the Americas. Various religious festivals are celebrated as national holidays, reflecting the country's multicultural and multi-religious heritage.

7.4. Major cities

The vast majority of Suriname's population, about 90%, lives in the capital, Paramaribo, or along the narrow coastal plain. Paramaribo is the dominant urban center, accounting for nearly half of the country's total population and most of its urban residents. Many other significant population centers are effectively part of Paramaribo's metropolitan area or are located along the coast.

{| class="wikitable"

! Rank !! City !! District !! Population (Approx. census/est.) !! Image

|-

| 1 || Paramaribo || Paramaribo || 223,757 || [[File:19530e4c6a7_d4edc8cb.JPG|width=3264px|height=2448px|100px|Waterfront of Paramaribo]]

|-

| 2 || Lelydorp || Wanica || 18,223 || [[File:1950f916193_e566bfd4.jpg|width=4000px|height=3000px|100px|Street in Lelydorp]]

|-

| 3 || Nieuw Nickerie || Nickerie || 13,143 || [[File:1952a3c1352_8238e763.jpg|width=3456px|height=2304px|100px|Water tower in Nieuw Nickerie]]

|-

| 4 || Moengo || Marowijne || 7,074 || [[File:1951cd37f9d_fa8614e5.jpg|width=700px|height=460px|100px|Bauxite factory in Moengo]]

|-

| 5 || Nieuw Amsterdam || Commewijne || 4,935 ||

|-

| 6 || Mariënburg || Commewijne || 4,427 ||

|-

| 7 || Wageningen || Nickerie || 4,145 ||

|-

| 8 || Albina || Marowijne || 3,985 ||

|-

| 9 || Groningen || Saramacca || 3,216 ||

|-

| 10 || Brownsweg || Brokopondo || 2,696 ||

|}

The interior of the country, largely covered by rainforest, is very sparsely populated, primarily by Maroon and Indigenous communities living in small villages along the rivers.

7.5. Emigration and diaspora

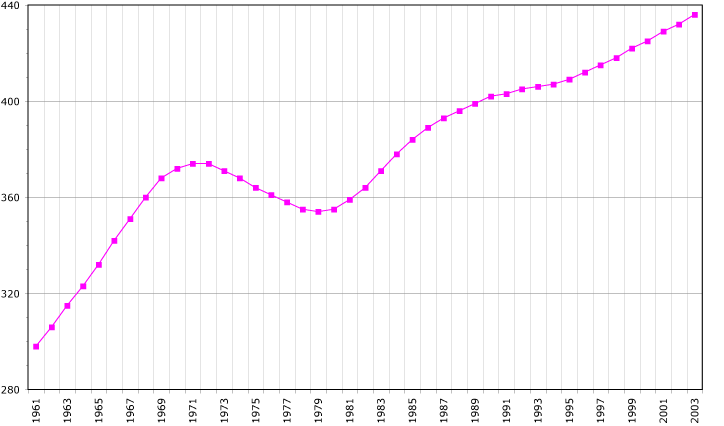

Emigration has significantly shaped Suriname's demographic profile. A major wave of emigration occurred in the years leading up to and immediately following independence in 1975, with many Surinamese choosing Dutch citizenship and moving to the Netherlands. This was driven by concerns about the new country's political and economic future. Migration continued during the period of military rule in the 1980s and for largely economic reasons throughout the 1990s.

As of 2013, the Surinamese community in the Netherlands numbered approximately 350,300 individuals (including children and grandchildren of Suriname migrants born in the Netherlands). This is a substantial diaspora relative to Suriname's own population of around 566,000 at that time. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in the late 2010s, around 272,600 people born in Suriname lived in other countries. The largest Surinamese diaspora communities are in:

- The Netherlands (approximately 192,000)

- France (approximately 25,000, mostly in neighboring French Guiana)

- The United States (approximately 15,000)

- Guyana (approximately 5,000)

- Aruba (approximately 1,500)

- Canada (approximately 1,000)

This emigration has led to a "brain drain" in some sectors but has also resulted in significant remittance flows back to Suriname and strong transnational cultural and economic ties, particularly with the Netherlands. The Surinamese diaspora plays an active role in the cultural and political life of both their host countries and Suriname.

8. Culture

Surinamese culture is a vibrant tapestry woven from the diverse traditions of its many ethnic groups, including Indigenous, African (Creole and Maroon), Indian (Hindustani), Javanese, Chinese, European (primarily Dutch), Lebanese and Jewish influences. This multicultural heritage is expressed in its languages, religions, festivals, cuisine, music, and arts, creating a unique cultural blend that is distinctly Surinamese.

[[File:194d9867bd0_25e30eaf.png|width=1510px|height=932px|thumb|left|Ketikoti (Emancipation Day) celebrations in Paramaribo, a significant cultural event commemorating the abolition of slavery.]]

[[File:194d9868514_84f8667b.PNG|width=1318px|height=899px|thumb|right|A Lion dance performance during Chinese New Year celebrations in Suriname, showcasing the cultural contributions of the Chinese-Surinamese community.]]

8.1. National holidays and festivals

Suriname celebrates a variety of national holidays that reflect its ethnic and religious diversity. These events are important expressions of cultural identity and social cohesion.

Secular National Holidays:

- January 1: New Year's Day

- May 1: Labour Day

- July 1: Ketikoti ({{lang|nl|Keti Koti|Broken Chains}}; Emancipation Day) - Commemorates the abolition of slavery in 1863. It is a major cultural event, especially for Afro-Surinamese communities, featuring traditional dress, music, food, and remembrance ceremonies.

- August 9: Indigenous People's Day - Celebrates the cultures and rights of Suriname's indigenous populations.

- October 10: Day of the Maroons - Honors the history, culture, and autonomy of the Maroon communities.

- November 25: Independence Day - Marks Suriname's independence from the Netherlands in 1975, celebrated with parades, official ceremonies, and cultural performances.

- December 25: Christmas Day

- December 26: Boxing Day

Religious Holidays (official public holidays, dates may vary based on lunar or religious calendars):

- Chinese New Year (January/February)

- Phagwah (Hindu festival of colors, March)

- Good Friday (Christian, March/April)

- Easter (Christian, March/April)

- Easter Monday (Christian, March/April)

- Diwali (Hindu festival of lights, October/November)

- Eid al-Fitr (Islamic festival marking the end of Ramadan, varies)

- Eid al-Adha (Islamic festival of sacrifice, varies)

- Satu Suro/Islamic New Year (Javanese/Islamic, varies)

Additionally, there are Arrival Days that commemorate the arrival of various immigrant groups, such as Indian Arrival Day, Javanese Arrival Day, and Chinese Arrival Day. These are important cultural observances for the respective communities, though not all are official public holidays for the entire nation.

New Year's Eve ({{lang|nl|Oud jaar|Old year}} or {{lang|srn|Owru Yari|Old year}}) is celebrated enthusiastically, often with loud displays of fireworks, especially long strings of firecrackers called {{lang|srn|pagara|pagara}} that are detonated at midnight to drive away evil spirits and welcome the new year.

[[File:194d98696b3_6cf65a0e.jpg|width=640px|height=480px|thumb|center|A pagara (long ribbon of firecrackers) being set off, a traditional part of New Year's Eve celebrations in Suriname.]]

8.2. Cuisine

[[File:1951840656d_2f73dbc9.JPG|width=640px|height=480px|thumb|left|Pom, a popular Surinamese oven dish often served at celebrations, typically made with chicken and tayer root.]]

Surinamese cuisine is a rich and eclectic fusion, reflecting the country's diverse ethnic makeup. It uniquely blends ingredients and cooking techniques from Indian (Hindustani/South Asian), African (West African influences brought by enslaved people, evolving into Creole and Maroon cuisines), Javanese (Indonesian), Chinese, Dutch, Jewish, Portuguese, and Indigenous culinary traditions. Each group has contributed distinct dishes and flavors, resulting in a vibrant national gastronomy.

Common staples include rice, root vegetables like cassava (manioc) and taro (locally known as {{lang|srn|tayer|tayer}}), and bread. Popular dishes showcase this fusion:

- Roti: A flatbread usually served with curried chicken, potatoes, and long beans; an influence from the Indo-Surinamese community.

- Nasi goreng and Bami goreng: Indonesian-style fried rice and fried noodles, adapted by the Javanese-Surinamese community.

- Pom: A festive oven dish of Creole origin, typically made with grated tayer root, chicken (or other meat/fish), citrus juice, and spices. It is often considered Suriname's national dish.

- {{lang|srn|Moksi Alesi|Mixed Rice}}: A Creole one-pot rice dish cooked with salted meat or fish, chicken, peas or beans, and coconut milk.

- {{lang|srn|Snesi Foroe|Chinese Chicken}}: Chinese-style chicken dishes.

- {{lang|srn|Moksi Meti|Mixed Meat}}: A dish featuring a variety of roasted or braised meats, often with Chinese or Creole influences.

- {{lang|srn|Losi Foroe|Braised Chicken}}: Braised chicken, often with vegetables.

- Peanut soup ({{lang|srn|Pindasoep|Peanut soup}})

- Bakkeljauw (salted codfish): Used in various preparations, often fried with onions, tomatoes, and peppers.

Vegetables like long beans ({{lang|srn|kousenband|kousenband}}), okra, and eggplant ({{lang|nl|antroewa|antroewa}}, {{lang|nl|bilambi|bilambi}}) are widely used. The fiery Madame Jeanette pepper is a staple for adding heat to dishes. Surinamese cuisine is known for its bold, complex flavors, achieved through the use of fresh herbs, spices, and a variety of condiments. Street food is also popular, with vendors offering items like roasted meats, fried snacks (e.g., {{lang|nl|bara|bara}}, {{lang|nl|phulauri|phulauri}}), and fresh fruit juices.

8.3. Music and performing arts

[[File:194d9868e48_31fcce80.png|width=1280px|height=704px|thumb|A performance at the Moengo Festival of Theatre and Dance in 2017, showcasing contemporary and traditional arts.]]

Surinamese music and performing arts are as diverse as its population, incorporating influences from African, European, Indian, Javanese, and Indigenous traditions.

Kaseko is perhaps the most well-known Surinamese music genre. The name may derive from the French phrase "{{lang|fr|casser le corps|break the body}}", referring to its energetic dance style. Kaseko is a fusion of various popular and folk styles, characterized by call-and-response vocals, complex rhythms played on percussion instruments like the {{lang|srn|skratji|large bass drum}} and snare drums, and melodies carried by wind instruments such as saxophones, trumpets, and occasionally trombones. It shares similarities with other Creole folk styles from the region, like {{lang|srn|kawina|kawina}}.

Baithak Gana is a traditional Indo-Surinamese musical form, typically performed by a small ensemble with vocals, harmonium, dholak (drum), and dhantal (percussion instrument). It is popular at social gatherings and religious ceremonies within the Hindustani community.

Other influential musical traditions include Javanese gamelan music, Chinese festival music, and various forms of religious music from Christian, Hindu, and Islamic traditions. Contemporary Surinamese artists often blend these traditional sounds with modern genres like reggae, dancehall, pop, and hip-hop.

Performing arts include traditional dances from different ethnic groups, storytelling, and theatre. The Moengo Festival of Theatre & Dance is a notable event that promotes contemporary and traditional arts. The biennial SuriPop (Suriname Popular Song Festival) is a major national music event that has launched the careers of many Surinamese artists. These cultural expressions are vital for maintaining community identity and fostering inter-cultural understanding.

8.4. Sports

[[File:194d9869a99_bcda71c1.jpg|width=2592px|height=1944px|thumb|left|The André Kamperveen Stadium in Paramaribo, a major venue for football and other sports.]]

[[File:194d986a3c1_f3d089e5.jpg|width=4080px|height=2296px|thumb|right|The Franklin Essed Stadium, another important sports facility in Suriname.]]

Sports play an important role in Surinamese society, with association football (soccer) being the most popular. Basketball and volleyball also have significant followings. The Suriname Olympic Committee is the national governing body for sports. Mind sports such as chess, draughts, bridge, and the local card game troefcall are also popular.

Suriname has a remarkable legacy in football, despite many talented players born in Suriname or of Surinamese descent choosing to represent the Netherlands national team. Famous examples include Gerald Vanenburg, Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard, Edgar Davids, Clarence Seedorf, Patrick Kluivert, Aron Winter, Georginio Wijnaldum, Virgil van Dijk, and Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink. In 1999, Humphrey Mijnals, who played for both Suriname and the Netherlands, was elected Surinamese footballer of the century. André Kamperveen, who captained Suriname in the 1940s and was the first Surinamese to play professionally in the Netherlands, is another legendary figure; the national stadium is named in his honor. The Suriname national team participated in its first CONCACAF Gold Cup in 2021.

[[File:194d986ac3f_5de7f40e.jpg|width=4000px|height=2129px|thumb|The Purcy R. Olivieira Sports Center, contributing to the development of various sports in Suriname.]]

In swimming, Anthony Nesty is Suriname's only Olympic medalist, winning gold in the 100-meter butterfly at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul and bronze in the same event at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona.

In track and field, Letitia Vriesde is the most famous international athlete, winning a silver medal in the 800 metres at the 1995 World Championships in Athletics (the first medal by a South American female athlete in World Championship history) and a bronze at the 2001 World Championships in Athletics, along with several Pan American Games and Central American and Caribbean Games medals. Tommy Asinga won a bronze medal in the 800 metres at the 1991 Pan American Games.

Cricket is popular, influenced by its prevalence in the Netherlands and neighboring Guyana. The Surinaamse Cricket Bond is an associate member of the International Cricket Council (ICC). Iris Jharap, born in Paramaribo, played women's One Day International matches for the Netherlands.

In badminton, notable players include Virgil Soeroredjo, Mitchel Wongsodikromo, Sören Opti, and Crystal Leefmans, who have won medals at Caribbean, Central American, and South American games. Soeroredjo (2012) and Opti (2016) represented Suriname at the Olympics, following Oscar Brandon.

Suriname has a strong tradition in kickboxing and martial arts, with several world champions born in Suriname or of Surinamese descent, such as Ernesto Hoost, Remy Bonjasky, Gilbert Ballantine, Rayen Simson, Melvin Manhoef, Tyrone Spong, Andy Ristie, Jairzinho Rozenstruik, Regian Eersel, and Donovan Wisse.

The national korfball team participates in korfball, a sport of Dutch origin. Vinkensport (finch-singing contests) is also practiced. The Sports Hall of Fame Suriname was established in 2016 to honor the achievements of Surinamese athletes.

8.5. World Heritage Sites

Suriname is home to two sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, recognizing their outstanding universal value to humanity. These sites reflect both the country's rich cultural history and its exceptional natural biodiversity.

1. Historic Inner City of Paramaribo (Inscribed 2002):

[[File:1950ba071ca_f3fbda81.jpg|width=870px|height=495px|thumb|center|330px|The waterfront of the Historic Inner City of Paramaribo, showcasing its unique colonial architecture.]]

The historic inner city of Paramaribo, the capital of Suriname, is an exceptional example of the gradual fusion of European architecture and construction techniques with indigenous South American materials and crafts. Established by Dutch colonists in the 17th and 18th centuries, the city features a distinctive and highly characteristic street plan of Dutch origin. Its wooden buildings, many of which are timber-framed with brick foundations and shingle roofs, exhibit a unique architectural style that evolved from Dutch and other European influences, adapted to the tropical climate. Notable structures include the Presidential Palace, Fort Zeelandia, the Ministry of Finance building, various churches including the wooden St. Peter and Paul Cathedral (one of the largest wooden structures in the Western Hemisphere), synagogues, and numerous residential and commercial buildings that retain their historical integrity. The site stands as a testament to the multicultural society of Suriname and the early colonial history of the Guiana region.

2. Central Suriname Nature Reserve (Inscribed 2000):

[[File:194d986d4be_0851a915.jpg|width=1600px|height=1071px|thumb|center|330px|An aerial view of the vast, untouched rainforest within the Central Suriname Nature Reserve.]]

The Central Suriname Nature Reserve is one of the largest ({{cvt|1.6|M|ha}}) and most pristine protected areas of tropical rainforest in the world. It encompasses a vast expanse of the Guiana Shield's ecosystem, characterized by its exceptional biodiversity. The reserve protects the upper watershed of the Coppename River and includes a range of topographical features from lowlands to mountains, including the Tafelberg (Table Mountain), Julianatop, and the Voltzberg dome. Its ecosystems harbor a rich diversity of flora and fauna, many species of which are endemic to the Guiana Shield region and some that are threatened globally. The reserve is crucial for the conservation of Amazonian biodiversity, providing habitat for species such as the jaguar, giant otter, tapir, sloths, eight species of primates, and over 400 bird species. Its inscription as a World Heritage Site acknowledges its ecological integrity and importance for in-situ conservation.

These World Heritage Sites highlight Suriname's commitment to preserving both its cultural and natural heritage for future generations and for the global community.

9. Transportation

Transportation in Suriname is shaped by its geography, with a concentration of infrastructure along the coastal plain and reliance on river and air transport for accessing the sparsely populated interior. A unique feature is that Suriname is one of only two countries on the mainland South American continent that drive on the left.

[[File:194d986b15c_85f508c4.jpg|width=3840px|height=2160px|thumb|The Jules Wijdenbosch Bridge spanning the Suriname River, connecting Paramaribo to Meerzorg and facilitating road transport to the eastern parts of the country.]]

9.1. Road transport

Suriname, along with neighboring [[Guyana]], drives on the left-hand side of the road. This practice is a legacy of its colonial history; one explanation is that the Netherlands itself used left-hand traffic at the time of Suriname's early colonization and also introduced it in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Another is that parts of Suriname were initially colonized by the British. Although the Netherlands converted to right-hand traffic in the late 18th century, Suriname did not change. Many vehicles imported into Suriname are left-hand-drive (designed for right-hand traffic), alongside right-hand-drive vehicles.

As of 2003, Suriname had approximately {{cvt|4303|km}} of roads, of which about {{cvt|1119|km}} were paved. The primary road network connects the main coastal towns, including Paramaribo, Nieuw Nickerie, Albina, and Moengo, via the East-West Link. The Jules Wijdenbosch Bridge over the Suriname River and the Coppename Bridge are significant structures on this route. Roads into the interior are limited and often unpaved, making travel difficult, especially during the rainy season. Public transportation mainly consists of buses and privately-owned minibuses (known as "particulieren") that operate on fixed routes, particularly in and around Paramaribo.

9.2. Air transport

[[File:194d986b9fb_fdeae7a4.jpg|width=4000px|height=3000px|thumb|The Johan Adolf Pengel International Airport, Suriname's main gateway for international air travel.]]

Air transport is crucial for international travel and for accessing remote areas in the interior. Suriname has approximately 55 airports and airstrips, most ofwhich are small and unpaved, serving interior villages. Only six have paved runways.

The main international airport is Johan Adolf Pengel International Airport (IATA: PBM, ICAO: SMJP), located near Zanderij, about {{cvt|45|km}} south of Paramaribo. It supports large jet aircraft and is the hub for international flights.

Airlines with regular departures from or arrivals in Suriname include:

- Surinam Airways (SLM) - The national airline, serving destinations in the Caribbean, Europe (Amsterdam), Brazil, Guyana, and the United States (Miami).

- KLM (Netherlands)

- American Airlines (United States)

- Caribbean Airlines (Trinidad and Tobago)

- Gol Transportes Aéreos (Brazil)

- Copa Airlines (Panama)

- TUI fly (Netherlands)

- Fly All Ways (a Surinamese airline serving regional destinations)

- Gum Air and Blue Wing Airlines (domestic airlines providing services to the interior)

Other national companies with air operator certification provide charter services, agricultural crop-dusting, missionary aviation, and flight training.

9.3. Water transport

Rivers have historically been, and remain, vital transportation arteries, especially for accessing the interior of Suriname where road infrastructure is sparse. Most major settlements in the interior are located along rivers. Dugout canoes ({{lang|srn|korjaal|korjaals}}), often motorized, are a common mode of transport for local communities and for ecotourism. Larger vessels and ferries operate on some of the main rivers and for coastal transport.

International ferry services connect Suriname with its neighbors:

- A ferry service operates across the Courantyne River between Nieuw Nickerie (Suriname) and Springlands (Guyana).

- A ferry service operates across the Marowijne River between Albina (Suriname) and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni (French Guiana).

Paramaribo has the country's main seaport, handling most international maritime cargo.

10. Health

[[File:194d986c440_9edcc98b.jpg|width=716px|height=254px|thumb|The Academic Hospital Paramaribo (AZP), the largest hospital in Suriname, playing a crucial role in the nation's healthcare system.]]

Suriname's healthcare system comprises a mix of public and private providers, with the government playing a significant role in policy, regulation, and service delivery, particularly through regional hospitals and primary care clinics. Access to healthcare, especially for vulnerable populations in remote interior regions, remains a challenge.

According to the Global Burden of Disease Study (data for 2017):

- The age-standardized death rate for all causes was 793 per 100,000 population (969 for males, 641 for females). This was considerably higher than some developed Caribbean nations like Bermuda (424) but lower than Haiti (1219). In 1990, the death rate was 960 per 100,000.

- Life expectancy at birth in 2017 was 72 years (69 for males, 75 for females).

- The death rate for children under 5 years was 581 per 100,000, significantly higher than in more developed regional countries but lower than in Haiti.

The leading causes of age-standardized death rates in both 1990 and 2017 were cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes/chronic kidney disease, reflecting a pattern common in many developing countries undergoing epidemiological transition with an increasing burden of non-communicable diseases. Infectious diseases such as malaria and HIV/AIDS remain public health concerns, though progress has been made in their control.

The main hospital is the Academic Hospital Paramaribo (AZP), which is the largest hospital in Suriname with 465 beds and serves as a teaching hospital. Other hospitals include the Diakonessenhuis and 's Lands Hospitaal in Paramaribo, and regional hospitals in districts like Nickerie and Marowijne. Healthcare in the interior is largely provided by the Medical Mission ({{lang|nl|Medische Zending|Medical Mission}}), which operates clinics and provides primary care services to Maroon and Indigenous communities.

Government health policies aim to improve access to care, strengthen primary healthcare, combat communicable and non-communicable diseases, and improve maternal and child health. Challenges include funding constraints, a shortage of specialized medical personnel (leading to some reliance on foreign doctors), and the logistical difficulties of providing services in remote areas. The welfare of minorities and vulnerable groups in accessing quality healthcare is a key consideration from a social liberalism perspective.

11. Education

[[File:194d986c7f0_6026bc5f.JPG|width=2337px|height=2432px|thumb|left|The main building of the Anton de Kom University of Suriname, the country's primary institution for higher education.]]

[[File:194d986d05c_35335a68.jpg|width=1750px|height=1183px|thumb|right|School children in Bigi Poika, an indigenous village, in 2006, illustrating educational efforts in rural communities.]]

Education in Suriname is compulsory for children from age 6 to 12. The education system is largely modeled on the Dutch system and Dutch is the language of instruction. The nation had a net primary enrollment rate of 94% in 2004, and literacy rates are relatively high, particularly among men.

The structure of the education system generally includes:

- Primary Education:** Typically 6 years. At the end of primary school, students take an exam to determine placement in secondary education.

- Secondary Education:** This is divided into several tracks. Students may attend MULO ({{lang|nl|Meer Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs|More Advanced Primary Education}}), which is a form of general secondary education, or lower vocational schools (LBO - {{lang|nl|Lager Beroepsonderwijs|Lower Vocational Education}}). After MULO, students can proceed to higher secondary schools (e.g., VWO - {{lang|nl|Voorbereidend Wetenschappelijk Onderwijs|Pre-university Secondary Education}}; HAVO - {{lang|nl|Hoger Algemeen Voortgezet Onderwijs|Higher General Secondary Education}}) which prepare them for tertiary education or higher vocational training. There are 13 grades from elementary school through high school.

- Higher Education:** The main institution for higher education is the Anton de Kom University of Suriname (AdeKUS) in Paramaribo, which offers faculties in social sciences, medical sciences, technological sciences, humanities, and mathematics & physics. There are also several teacher training colleges, technical institutes, and other specialized post-secondary institutions.

Challenges in the education system include ensuring equitable access and quality, particularly for children in remote interior regions where resources may be scarce and qualified teachers difficult to retain. Dropout rates, especially at the secondary level, are a concern. Curricula sometimes face criticism for not being sufficiently adapted to the local Surinamese context or the needs of a diverse student population. Efforts to improve teacher training, update curricula, and invest in educational infrastructure are ongoing. From a social liberalism perspective, ensuring equal educational opportunities for all ethnic groups and socio-economic classes, including vulnerable and minority children, is crucial for democratic development and social progress.

12. Media

The media landscape in Suriname includes a variety of newspapers, radio stations, television broadcasters, and online news outlets. Dutch is the primary language of most mainstream media.

Newspapers:

Traditionally, De Ware Tijd has been the major daily newspaper. Since the 1990s, other prominent newspapers include Times of Suriname, De West, and Dagblad Suriname. These are all published primarily in Dutch.

Radio:

Suriname has approximately twenty-four radio stations, catering to diverse tastes and linguistic groups. Many also broadcast online.

Television:

There are around twelve television broadcasters. Some of the main channels include:

- Ampie's Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) (Ch. 4)

- RBN (Ch. 5)

- Rasonic TV (Ch. 7)

- STVS ({{lang|nl|Surinaamse Televisie Stichting|Surinamese Television Foundation}}) (Ch. 8) - the state-owned national broadcaster.

- Apintie Televisie (Ch. 10)

- ATV (Algemene Televisie Verzorging) (Ch. 12)

- Radika (Ch. 14)

- SCCN (Ch. 17)

- Pipel TV (Ch. 18)

- Trishul (Ch. 20)

- Garuda (Ch. 23)

- Sangeetmala (Ch. 26)

- SCTV (Ch. 45)

There are also channels such as Ch. 30, Ch. 31, Ch.32, Ch.38. mArt, a broadcaster based in Amsterdam founded by people from Suriname, is also listened to.

Online Media:

Several online news websites are popular, including Starnieuws, Suriname Herald, and GFC Nieuws, providing up-to-date news and information.

Cartoons:

Kondreman is a popular cartoon character and series in Suriname.

Press Freedom:

Press freedom is generally respected, but there have been concerns at times regarding political influence or pressure on journalists. In 2022, Suriname was ranked 52nd in the worldwide Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders. This represented a drop in ranking compared to the 2018-2021 period when it was ranked around 20th. Ensuring a free, independent, and diverse media is crucial for democratic accountability and the representation of various societal perspectives, including those of minority and vulnerable groups.

13. Tourism

Tourism in Suriname is a developing sector with significant potential, primarily centered on its vast, pristine rainforests, rich biodiversity, unique cultural heritage, and historical sites. The country offers a distinct experience compared to more mainstream Caribbean or South American destinations.