1. Biography

Nikos Kazantzakis's life was marked by extensive travels, deep intellectual engagement, and a consistent pursuit of personal and spiritual freedom, which heavily influenced his literary output.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Nikos Kazantzakis was born on March 2, 1883 (February 18, 1883, Old Style) in Kandiye, which is now known as Heraklion, on the island of Crete. At the time of his birth, Crete was still under the rule of the Ottoman Empire and had not yet joined the modern Greek state, which had been established in 1832. His family originated from the village of Myrtia. His father, Michalis Kazantzakis, was a middle-class grain and wine merchant. Growing up in Ottoman-ruled Crete, Kazantzakis experienced the persecution of Christians, which shaped his early nationalist sentiments. In 1897, as the Greek rebellion against the Ottomans intensified on Crete, his family sought refuge and temporarily relocated to Naxos. He completed his secondary education in Crete.

1.2. Academic Pursuits and Early Literary Endeavors

From 1902 to 1906, Kazantzakis pursued legal studies at the University of Athens. In 1906, he completed his Juris Doctor thesis, titled Ο Φρειδερίκος Νίτσε εν τη φιλοσοφία του δικαίου και της πολιτείαςGreek, Modern ("Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Law and the State"), indicating an early interest in philosophy. During his university years, he also contributed columns to Athens newspapers and published his first works, including the essay Sick Times, the novel Serpent and Lily (1906), which he signed with the pen name Karma Nirvami, and the play Dawn (1907).

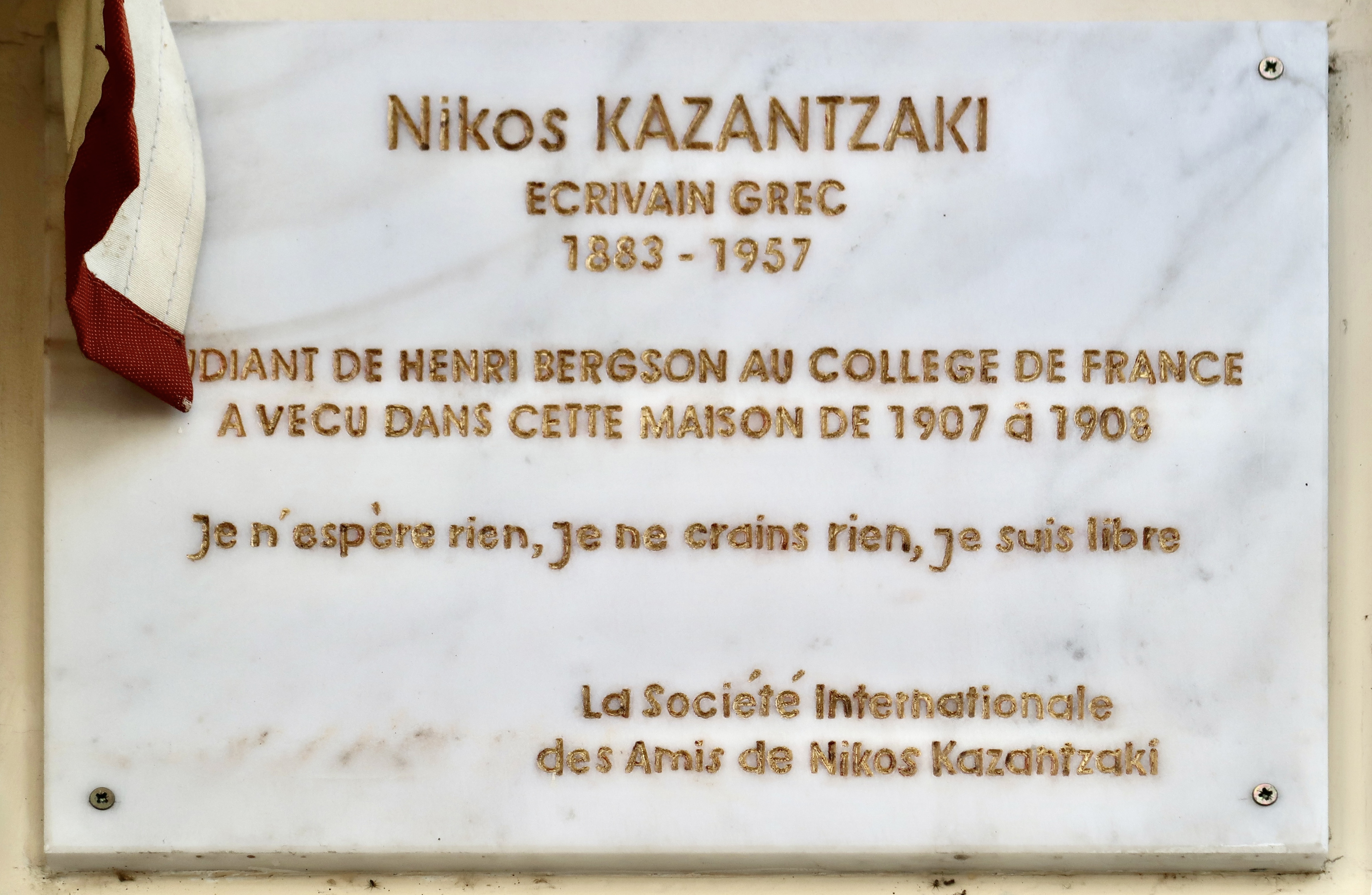

In 1907, Kazantzakis moved to Paris to study philosophy at the Sorbonne. There, he was profoundly influenced by the philosophies of Henri Bergson, particularly the idea that a true understanding of the world arises from a combination of intuition, personal experience, and rational thought. He was also deeply impacted by the works of Friedrich Nietzsche. In 1909, his doctoral dissertation at the Sorbonne was a reworked version of his 1906 thesis, titled Friedrich Nietzsche dans la philosophie du droit et de la cité ("Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Right and the State"). Upon his return to Greece, he began translating various philosophical works into Greek. In 1914, he met the acclaimed writer Angelos Sikelianos, and for two years, they embarked on travels through regions where Greek Orthodox Christian culture flourished, largely inspired by Sikelianos's fervent nationalism.

1.3. Marriages and Personal Life

In 1911, Kazantzakis married Galateia Alexiou, a fellow student and writer. Their marriage concluded in divorce in 1926. He met Eleni Samiou (Helen) in 1924, and their romantic relationship began in 1928, though they did not marry until 1945. Eleni Samiou played a crucial role in Kazantzakis's life and work, assisting him by typing drafts, accompanying him on his numerous travels, and managing his business affairs. They remained married until his death in 1957. Eleni Samiou passed away in 2004.

1.4. Extensive Travels and Ideological Evolution

Between 1922 and his death in 1957, Kazantzakis embarked on extensive journeys across the globe, which profoundly shaped his philosophical and ideological development. His travels included sojourns in Paris and Berlin (from 1922 to 1924), Italy, Russia (in 1925 and 1927), Spain (in 1932), and later Cyprus, Aegina, Egypt, Mount Sinai, Czechoslovakia, Nice (where he later acquired a villa in nearby Antibes), China, and Japan.

While in Berlin, amidst a volatile political climate, Kazantzakis encountered and became an admirer of communism and Vladimir Lenin. Although he never fully committed to being a communist, he visited the Soviet Union twice, in 1925 and 1927, staying with the Left Opposition politician and writer Victor Serge. However, witnessing the rise of Joseph Stalin and the realities of Soviet-style communism, particularly after the Lusakov affair, led to his disillusionment with the system. Around this period, his earlier nationalist convictions gradually gave way to a more universalist ideology. As a journalist, he conducted interviews with notable figures such as Spanish Prime Minister Miguel Primo de Rivera and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini in 1926. In 1922, he also spent time in Vienna, where he delved into the study of Buddhism. In 1935, he visited Japan and China, a journey that inspired his travelogue Japan, China (1938). These extensive travels exposed him to diverse philosophies, ideologies, and lifestyles, all of which deeply influenced him and his writings.

1.5. Political and Public Service

Kazantzakis engaged in public life on several occasions. In 1912, he volunteered for military service during the First Balkan War and served in the private office of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. In 1917, he ventured into a coal mining and logging business in his native Crete with a man named Giorgos Zorbas, an experience that later became the basis for his famous novel Zorba the Greek.

In 1919, he was appointed director of the Public Welfare Ministry by Prime Minister Venizelos. In this role, he successfully undertook the significant task of repatriating approximately 150,000 Greek refugees, including Pontic Greeks, from the Caucasus and Southern Russia following World War I. He resigned this position the following year after Venizelos's Liberal Party suffered an electoral defeat.

During World War II, specifically from 1941 to 1944, while Greece was under German occupation, Kazantzakis resided in Athens and Aegina. During this time, he collaborated with the philologist Ioannis Kakridis on a translation of Homer's Iliad. After the German forces withdrew from Greece in 1944, he returned to Athens and directly witnessed the devastating December Events, a period of intense civil conflict.

Motivated to re-enter politics, Kazantzakis became the leader of a small non-communist leftist party. In 1945, he was appointed Minister without Portfolio in the provisional government formed by Themistoklis Sophoulis. That same year, he was also a founding member of the Greek-Soviet friendship union. He resigned from his ministerial post the following year. In 1946, Kazantzakis assumed the role of head of the UNESCO Bureau of Translations, an organization dedicated to promoting the translation of literary works. However, he resigned in 1947 to dedicate himself fully to writing, a period during which he produced the majority of his most significant literary works.

1.6. Death and Burial

In late 1957, despite suffering from leukemia, Kazantzakis embarked on one final journey to China and Japan. According to one theory, while in China, he had to be vaccinated, possibly due to symptoms of smallpox and cholera. This vaccination is believed to have caused gangrene. At the expense of the Chinese government, he was transported first to Copenhagen and then to Freiburg, Germany, for treatment. Although the gangrene was cured, he contracted a severe form of Asian flu in China, which ultimately led to his death. During this final illness, he also had a meeting with Albert Schweitzer.

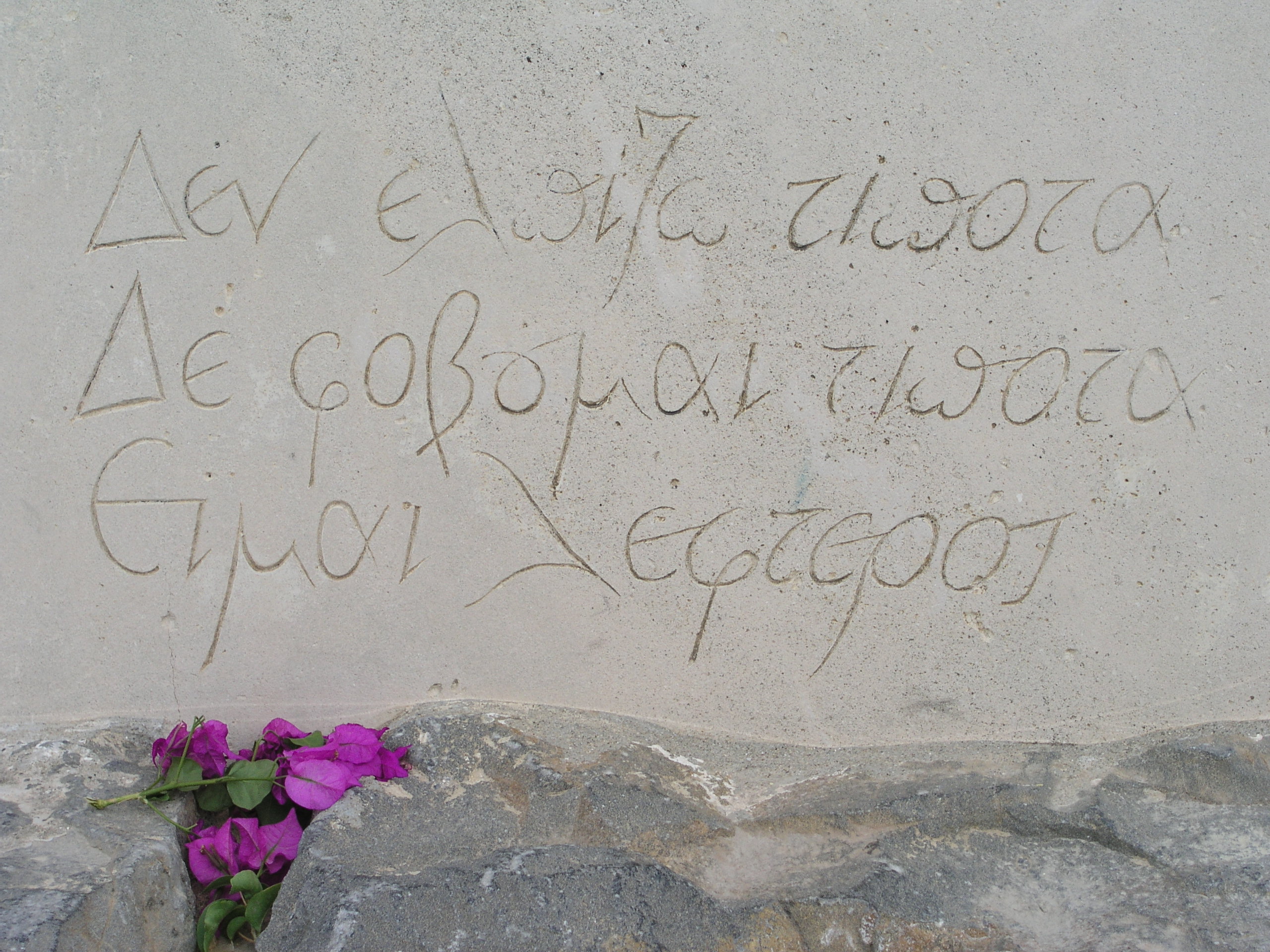

Nikos Kazantzakis died on October 26, 1957, in Freiburg, Germany, at the age of 74. His body was initially returned to Athens, but the Greek Orthodox Church there refused to grant him a burial ceremony due to his controversial works and views. Consequently, his remains were transported to his hometown of Heraklion, Crete. A ceremony was held at Agios Minas Cathedral, and he was interred at the highest point of the Walls of Heraklion, specifically the Martinengo Bastion, which offers a panoramic view of the mountains and the Cretan Sea. His tomb, reminiscent of an Egyptian-style mausoleum, bears a famously pithy epitaph that he had personally requested: "I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free." (Δεν ελπίζω τίποτα. Δε φοβούμαι τίποτα. Είμαι λέφτερος.Greek, Modern). This phrasing is believed to reflect a philosophical ideal of Cynicism that dates back to at least the second century CE.

2. Literary Works and Themes

Nikos Kazantzakis's literary output is characterized by its distinctive style, profound philosophical depth, and exploration of fundamental human struggles, drawing from a wide array of intellectual and cultural influences.

2.1. Characteristics and Core Themes

The overarching features and central themes of Kazantzakis's literature include his relentless exploration of human freedom, intense spiritual struggle, and pervasive existential themes. These were deeply shaped by his engagement with the philosophies of Henri Bergson and Friedrich Nietzsche, as well as his studies in Buddhism. He often depicted a dynamic interplay between rational thought and irrational human experience, a theme central to many of his characters and personal philosophies. Kazantzakis believed that a true understanding of the world emerged from the combination of intuition, personal experience, and reason, a concept he derived from Bergson.

His works frequently explore the unique geopolitical and spiritual position of Greece, a nation situated between the East and the West. Kazantzakis posited that Greece's special mission was to reconcile "Eastern instinct with Western reason," echoing the Bergsonian balance between logic and emotion. Furthermore, his post-World War II novels extensively delve into various aspects of Greek culture, including religion, nationalism, political beliefs, the impact of the Greek Civil War, gender roles, immigration, and general societal practices and beliefs. Rather than strictly adhering to plot-driven narratives, Kazantzakis's works often prioritized the flow and development of his philosophical ideas.

2.2. The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel

Kazantzakis began writing The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel in 1924, a monumental epic poem that took him fourteen years to complete and revise, finally publishing it in 1938. The poem continues the narrative of Homer's Odyssey, following the hero Odysseus on a final, transformative journey after the events of the original epic. Mirroring the structure of Homer's work, it is divided into 24 rhapsodies and comprises an impressive 33,333 lines.

Kazantzakis himself regarded this poem as his greatest literary achievement, believing it to be a culmination of his cumulative wisdom and experience. However, its critical reception was divided; some literary critics lauded it as an unprecedented epic, while many others viewed it as a "hybristic act," a divergence of opinion that persists among scholars today. A frequent criticism directed at The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel was its perceived over-reliance on flowery and metaphorical verse, a stylistic characteristic that also drew criticism in his works of fiction.

2.3. Novels

Many of Kazantzakis's most renowned novels were published between 1940 and 1961, gaining him international acclaim and often sparking significant cultural and religious discussions.

His first published novel was Serpent and Lily (Όφις και ΚρίνοGreek, Modern), released in 1906 under the pen name Karma Nirvami. In 1908, he serialized Broken Souls (Σπασμένες ΨυχέςGreek, Modern, Spasmenes Psyches) in O Numas magazine, though this work remains untranslated into English.

Zorba the Greek (Βίος και πολιτεία του Αλέξη ΖορμπάGreek, Modern, Víos kai politeía tou Aléxē Zorbá), published in 1946 (originally titled Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas), is one of his most celebrated works. It draws inspiration from Kazantzakis's own failed coal mining and logging venture in 1917 and his real-life associate, Giorgos Zorbas. The novel explores themes of freedom, sensuality, and the human spirit through its titular character.

Christ Recrucified (Ο Χριστός ξανασταυρώνεταιGreek, Modern, O Christós Xanastavrόnetai), published in 1948 (known as The Greek Passion in the United States), delves into profound questions of Christian morality and values. It explores the controversies between religious beliefs and their application in societal issues, often set against the backdrop of a traditional Greek village.

Captain Michalis (Ο Καπετάν ΜιχάληςGreek, Modern, O Kapetán Mikhális), published in 1953 and translated as Freedom or Death, is a historical novel set during the Cretan Revolt of 1889. This work, along with The Last Temptation of Christ, faced severe criticism from the Greek Orthodox Church.

The Last Temptation of Christ (Ο τελευταίος πειρασμόςGreek, Modern, O Teleftéos Pirasmós), published in 1955, remains his most controversial novel. It depicts Jesus Christ as a human figure grappling with doubts, fears, and temptations, leading to strong condemnations from both the Greek Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, which placed it on its Index of Forbidden Books.

Other notable novels include Saint Francis (Ο Φτωχούλης του ΘεούGreek, Modern, O Ftochoúlis tou Theoú), 1956, published in 1962 (titled God's Pauper: Saint Francis of Assisi in the UK), an imaginative biography of Francis of Assisi. Report to Greco (Αναφορά στον ΓκρέκοGreek, Modern, Anaforá ston Gkréko), published posthumously in 1961, is an autobiographical work reflecting on his intellectual and spiritual journey. He also wrote The Rock Garden (1936), originally in French, and Toda Raba (1930), also originally in French, which was influenced by his experiences in the Soviet Union. His works also include The Fratricides (1953) and children's novels such as Alexander the Great: A Novel (1940) and At the Palaces of Knossos: A Novel (1940). The novel The Ascent (Ο ΑνήφοροςGreek, Modern, O Aniforos), written in 1946, was first published in 2022 and has not yet been translated into English.

2.4. Plays and Other Writings

Kazantzakis explored a diverse range of genres beyond novels and epic poetry, including plays, travel books, philosophical essays, and memoirs.

His plays often delved into existential and philosophical themes. These include Comedy (1909), a one-act play with strong existential undertones, and The Master Builder (Ο ΠρωτομάστοραςGreek, Modern), which draws upon a popular Greek folkloric myth. His other theatrical works include Julian the Apostate, first staged in Paris in 1948, and Buddha (1983). He also authored plays such as Melissa, Kouros, Christopher Columbus, and Sodom and Gomorrah.

Kazantzakis was an avid traveler, and his journeys across continents resulted in several travelogues. These include Spain (1963), Japan, China (Ταξιδεύοντας. Ιαπωνία-ΚίναGreek, Modern), published in 1938 and documenting his experiences in Asia, England (1965), Journey to the Morea (1965), and Journeying: Travels in Italy, Egypt, Sinai, Jerusalem and Cyprus (1975). He also documented his experiences in Russia (1940). Some of his travel writings, such as Mediterranean Journey (Μεσογειακά ΤαξίδιαGreek, Modern), remain untranslated.

Among his significant non-fiction works is the philosophical essay The Saviours of God: Spiritual Exercises (ΑσκητικήGreek, Modern, Asketiki), originally published in 1922 as Asceticism, which outlines his spiritual philosophy. His doctoral dissertation, Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Right and the State, was published in English in 2007. His collected writings also include memoirs and various essays, such as Symposium (1922) and Drama and Contemporary Man: An Essay. A selection of his personal correspondence was published as The Suffering God: Selected Letters to Galatea and to Papastephanou and The Selected Letters of Nikos Kazantzakis.

He also authored short stories, notably "He Wants to Be Free - Kill Him!" (1963). While primarily known for his prose and epic poem, Kazantzakis also wrote poetry, including the collection Tertsines (1932-1937), published posthumously in 1960 and currently untranslated. He also wrote Christ (poetry). Additionally, he produced a History of Russian Literature (1930), originally written in French.

2.5. Language and Style: Use of Demotic Greek

During the period when Kazantzakis was writing his novels, poems, and plays, the majority of "serious" Greek literary works were composed in Katharevousa. This "pure" form of the Greek language was conceived to bridge Ancient Greek with Modern, Demotic Greek, with the intention of "purifying" Demotic Greek. However, the use of Demotic among writers gradually began to gain prominence around the turn of the 20th century, largely under the influence of the New Athenian School (or Palamian School).

Kazantzakis deliberately chose to write in Demotic Greek, a decision he explained in his letters to friends and correspondents. His primary aim was to capture the authentic spirit of the Greek people and ensure that his writing resonated with the common Greek citizen. He explicitly sought to demonstrate that the vernacular, spoken language of Greece was fully capable of producing high artistic and literary works, posing the question: "Why not show off all the possibilities of Demotic Greek?" Furthermore, Kazantzakis felt it was essential to record the vernacular of everyday people, including Greek peasants. He frequently endeavored to incorporate expressions, metaphors, and idioms he encountered during his travels throughout Greece into his writing, preserving them for posterity.

At the time, his choice of language sparked controversy. Some scholars and critics condemned his work precisely because it was not written in Katharevousa, while others praised him for his commitment to Demotic Greek. Despite his use of Demotic, several critics argued that Kazantzakis's writing was "too flowery, filled with obscure metaphors, and difficult to read." However, Kazantzakis scholar Peter Bien contended that the metaphors and language Kazantzakis employed were directly drawn from the peasants he met while traveling across Greece. Bien asserted that, in his effort to preserve the language of the people, Kazantzakis utilized their local metaphors and phrases to lend his narrative an air of authenticity and to prevent these expressions from being lost.

3. Philosophy and Ideology

Nikos Kazantzakis's intellectual framework was characterized by a relentless spiritual quest, an evolving political consciousness, and a critical engagement with societal norms.

3.1. Religious Beliefs and Relationship with the Greek Orthodox Church

While Nikos Kazantzakis was profoundly spiritual throughout his life, he frequently articulated his struggle with religious faith, particularly his Greek Orthodoxy. Baptized Greek Orthodox as a child, he developed a fascination with the lives of saints from a young age. As a young man, he undertook a month-long trip to Mount Athos, a significant monastic retreat and major spiritual center for Greek Orthodoxy.

Most critics and scholars of Kazantzakis agree that the profound struggle to find truth in religion and spirituality was central to many of his works. Novels such as The Last Temptation of Christ and Christ Recrucified are entirely dedicated to questioning Christian morals and values. As he traveled across Europe, he was influenced by various philosophers, cultures, and religions, including Buddhism, which led him to critically re-evaluate his traditional Christian beliefs. Although he never claimed to be an atheist, his public questioning and critiques often put him at odds with segments of the Greek Orthodox Church and many conservative literary critics.

Scholars theorize that Kazantzakis's difficult relationship with many members of the clergy and with more religiously conservative literary critics stemmed from his unconventional interpretations. In his book Broken Hallelujah: Nikos Kazantzakis and Christian Theology, author Darren Middleton proposes that, "Where the majority of Christian writers focus on God's immutability, Jesus' deity, and our salvation through God's grace, Kazantzakis emphasized divine mutability, Jesus' humanity, and God's own redemption through our effort." This highlights Kazantzakis's unique and often challenging interpretation of traditional Orthodox Christian beliefs.

Many Orthodox Church clergy members openly condemned Kazantzakis's work, and a campaign was initiated to excommunicate him. His famous reply to this condemnation was: "You gave me a curse, Holy fathers, I give you a blessing: may your conscience be as clear as mine and may you be as moral and religious as I" (Μου δώσατε μια κατάρα, Άγιοι πατέρες, σας δίνω κι εγώ μια ευχή: Σας εύχομαι να 'ναι η συνείδηση σας τόσο καθαρή, όσο είναι η δική μου και να 'στε τόσο ηθικοί και θρήσκοι όσο είμαι εγώGreek, Modern). While the excommunication attempt was ultimately rejected by the top leadership of the Orthodox Church, it became emblematic of the persistent disapproval his political and religious views received from many Christian authorities, especially after the Roman Catholic Church placed The Last Temptation of Christ on its Index of Forbidden Books.

Despite the controversies, modern scholarship tends to dismiss the notion that Kazantzakis was being sacrilegious or blasphemous with the content of his novels and beliefs. These scholars argue that, if anything, Kazantzakis acted in accordance with a long tradition of Christians who publicly wrestled with their faith, ultimately developing a stronger and more personal connection to God through their doubts. Furthermore, scholars like Darren J. N. Middleton contend that Kazantzakis's interpretation of the Christian faith predated the more modern, personalized interpretation of Christianity that has become popular in the years following his death.

3.2. Social and Political Views

Throughout his life, Nikos Kazantzakis consistently reiterated his conviction that "only socialism as the goal and democracy as the means" could provide an equitable solution to the "frightfully urgent problems of the age in which we are living." He saw a crucial need for socialist parties worldwide to set aside their internal disputes and unite, envisioning a future where the program of "socialist democracy" would prevail not only in Greece but across the civilized world. He defined socialism as a social system that "does not permit the exploitation of one person by another" and that "must guarantee every freedom."

Kazantzakis was often anathema to the right-wing in Greece, both before and after World War II. The right-wing frequently waged campaigns against his books, labeling him as "immoral" and a "Bolshevik troublemaker," and even accusing him of being a "Russian agent." Ironically, he was also viewed with distrust by both the Communist Party of Greece and the Soviet Union, which often dismissed him as a "bourgeois" thinker. However, upon his death in 1957, he received an unexpected honor from the Chinese Communist Party, which recognized him as a "great writer" and "devotee of peace."

Following World War II, Kazantzakis temporarily assumed the leadership of a minor Greek leftist party. In 1945, he was, among others, a founding member of the Greek-Soviet friendship union. His initial nationalist beliefs, prevalent in his early life, gradually evolved into a more universalist ideology as he traveled and experienced different political systems, leading him to critically examine social inequality and human exploitation.

4. Legacy and Recognition

Nikos Kazantzakis's enduring impact is reflected in his multiple international nominations for prestigious awards, the widespread adaptation of his works into film, and various commemorations dedicated to his memory.

4.1. Nobel Prize Nominations

Nikos Kazantzakis was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in nine different years, a testament to his significant literary standing. In 1946, The Society of Greek Writers formally recommended both Kazantzakis and Angelos Sikelianos for the prestigious award. His nominations were recorded in 1947 and 1950. In 1957, in a particularly close contest, he narrowly lost the prize to Albert Camus by a single vote. Camus himself later publicly acknowledged Kazantzakis's profound literary merit, stating that he deserved the honor "a hundred times more" than himself.

4.2. Film Adaptations

Kazantzakis's novels have been successfully adapted into cinema, bringing his narratives to a global audience and often stirring significant cultural and religious debate.

His novel Christ Recrucified was adapted into the film He Who Must Die (1957), directed by the blacklisted American filmmaker Jules Dassin in France.

Zorba the Greek was famously adapted into the acclaimed film Zorba the Greek (1964), directed by the Greek filmmaker Michael Cacoyannis. The film was a critical and commercial success, winning three Oscars in 1965. Anthony Quinn's iconic portrayal of the titular character, Zorba, contributed significantly to the novel's international popularity.

The Last Temptation of Christ was adapted into the controversial film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), directed by Martin Scorsese. The film's production faced initial cancellation due to its sensitive subject matter but was eventually completed after six years. Upon its release, it generated widespread controversy and significant protests from various Christian groups, particularly Catholic organizations, due to its depiction of Jesus as a human figure grappling with temptation.

In addition to these adaptations, a biographical film titled Kazantzakis (2017), directed by Yannis Smaragdis, was released, offering a cinematic portrayal of the author's life.

4.3. Commemorations

Various tributes and memorials have been dedicated to Nikos Kazantzakis, recognizing his enduring legacy in Greek and world literature. The 50th anniversary of his death in 2007 was selected as the main motif for a high-value euro collectors' coin: the €10 Greek Nikos Kazantzakis commemorative coin. His image is featured on the obverse of the coin, while the reverse displays the National Emblem of Greece alongside his signature.

In his hometown of Heraklion, Crete, a medallion honoring Kazantzakis is prominently displayed in the Venetian loggia. Additionally, a bust of the author stands as a tribute in Heraklion. The Nikos Kazantzakis Museum in Myrtia, Crete, is dedicated to his life and works, preserving his memory and promoting his literary contributions. The Historical Museum of Crete also features dedicated pages to Nikos Kazantzakis, providing insight into his life and historical context.

5. Bibliography

This section provides a categorized list of Nikos Kazantzakis's major works, primarily focusing on those translated into English.

5.1. Epic Poem

- The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel (ΟδύσσειαGreek, Modern, 1938)

- The Odyssey [Selections from], partial prose translation by Kimon Friar, 1953.

- The Odyssey, excerpt translated by Kimon Friar, 1954.

- "The Return of Odysseus", partial translation by Kimon Friar, 1955.

- The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, full verse-translation by Kimon Friar, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1958; London: Secker and Warburg, 1958.

- "Death, the Ant", from The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, Book XV, 829-63, trans. Kimon Friar, 1960.

- Odysseus: A Verse Tragedy, trans. Kostas Myrsiades, Boston: Somerset Hall Press, 2022.

5.2. Novels

- Serpent and Lily (Όφις και ΚρίνοGreek, Modern, 1906), trans. Theodora Vasils, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

- Zorba the Greek (Βίος και πολιτεία του Αλέξη ΖορμπάGreek, Modern, 1943), trans. Carl Wildman, London: John Lehmann, 1952; New York: Simon & Schuster, 1953; new trans. Peter Bien, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014.

- The Greek Passion (Ο Χριστός ξανασταυρώνεταιGreek, Modern, 1948), trans. Jonathan Griffin, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1954; published in the United Kingdom as Christ Recrucified, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1954.

- Freedom or Death (Ο Καπετάν ΜιχάληςGreek, Modern, 1950), trans. Jonathan Griffin, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1954; and in the United Kingdom Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1956.

- The Last Temptation (Ο τελευταίος πειρασμόςGreek, Modern, 1951), trans. Peter A. Bien, New York, Simon & Schuster, 1960.

- Saint Francis (Ο Φτωχούλης του ΘεούGreek, Modern, 1956), trans. Peter A. Bien, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1962; published in the United Kingdom as God's Pauper: Saint Francis of Assisi, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1962.

- The Rock Garden (originally French: Le Jardin des rochersFrench, 1936), trans. Richard Howard, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- The Fratricides (Οι ΑδελφοφάδεςGreek, Modern, 1953), trans. Athena Gianakas Dallas, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1964.

- Toda Raba (originally French, 1930), trans. Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1964.

- Report to Greco (Αναφορά στον ΓκρέκοGreek, Modern, 1957), trans. Peter A. Bien, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965.

- Alexander the Great: A Novel (for children) (1940), trans. Theodora Vasils, Athens (Ohio): Ohio University Press, 1982.

- At the Palaces of Knossos: A Novel (for children) (1940), trans. Themi and Theodora Vasilis, ed. Theodora Vasilis, London: Owen, 1988.

- Father Yanaros [from the novel The Fratricides], trans. Theodore Sampson, in Modern Greek Short Stories, vol. 1, ed. Kyr. Delopoulos, Athens: Kathimerini Publications, 1980.

5.3. Plays

- Comedy: A Tragedy in One Act (1909), trans. Kimon Friar, The Literary Review 18, No. 4 (Summer 1975).

- The Master Builder (Ο ΠρωτομάστοραςGreek, Modern, 1910), trans. Kohsuke Fukuda, 京緑社, 2022.

- Julian the Apostate (first staged in Paris, 1948).

- Three Plays: Melissa, Kouros, Christopher Columbus, trans. Athena Gianakas-Dallas, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969.

- Christopher Columbus, trans. Athena Gianakas-Dallas, Kentfield (CA): Allen Press, 1972.

- From Odysseus: A Drama, partial translation by M. Byron Raizis, The Literary Review 16, No. 3 (Spring 1973).

- Sodom and Gomorrah, A Play (1976), trans. Kimon Friar, The Literary Review 19, No. 2 (Winter 1976).

- Two plays: Sodom and Gomorrah and Comedy: A Tragedy in One Act, trans. Kimon Friar, Minneapolis: North Central Publishing Co., 1982.

- Buddha, trans. Kimon Friar and Athena Dallas-Damis, San Diego: Avant Books, 1983.

- Kapodistrias (1946, staged).

- Apostate Julius (1959, staged).

- Melissa (1962, staged).

5.4. Travel Books

- Spain (1926), trans. Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- Japan, China (Ταξιδεύοντας: Ιαπωνία-ΚίναGreek, Modern, 1938), trans. George C. Pappageotes, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

- England (1939), trans. Amy Mims, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965.

- Journey to the Morea (1937), trans. by F. A. Reed, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965.

- Journeying: Travels in Italy, Egypt, Sinai, Jerusalem and Cyprus (1926-1927), trans. Themi Vasils and Theodora Vasils, Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1975.

- Russia (1940), trans. A. Maskaleris and M. Antonakis, San Francisco: Creative Arts Books Co, 1989.

5.5. Short Stories

- "He Wants to Be Free - Kill Him!", trans. Athena G. Dallas, Greek Heritage 1, No. 1 (Winter 1963).

5.6. Poems

- Christ (poetry), trans. Kimon Friar, Journal of Hellenic Diaspora (JHD) 10, No. 4 (Winter 1983).

5.7. Memoirs, Essays, and Letters

- The Saviours of God: Spiritual Exercises (ΑσκητικήGreek, Modern, 1922), trans. Kimon Friar, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1960.

- Report to Greco (Αναφορά στον ΓκρέκοGreek, Modern, 1957), trans. Peter A. Bien, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1965.

- Symposium (ΣυμπόσιονGreek, Modern, 1922), trans. Theodora Vasils and Themi Vasils, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1974.

- Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Right and the State (doctoral dissertation), trans. O. Makridis, New York: State University of NY Press, 2007.

- From The Saviours of God: Spiritual Exercises, trans. Kimon Friar, The Charioteer, No. 1 (Summer 1960).

- The Suffering God: Selected Letters to Galatea and to Papastephanou, trans. Philip Ramp and Katerina Anghelaki Rooke, New Rochelle (NY): Caratzas Brothers, 1979.

- The Angels of Cyprus, trans. Amy Mims, in Cyprus '74: Aphrodite's Other Face, ed. Emmanuel C. Casdaglis, Athens: National Bank of Greece, 1976.

- Burn Me to Ashes: An Excerpt, trans. Kimon Friar, Greek Heritage 1, No. 2 (Spring 1964).

- Drama and Contemporary Man: An Essay, trans. Peter Bien, The Literary Review 19, No. 2 (Winter 1976).

- The Homeric G.B.S., The Shaw Review 18, No. 3 (Sept. 1975).

- Hymn (Allegorical), trans. M. Byron Raizis, Spirit 37, No. 3 (Fall 1970).

- Two Dreams, trans. Peter Mackridge, Omphalos 1, No. 2 (Summer 1972).

- The Selected Letters of Nikos Kazantzakis, ed. and tr. Peter Bien, Princeton Modern Greek Studies, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

- A Tiny Anthology of Kazantzakis: Remarks on the Drama, 1910-1957, compiled by Peter Bien, The Literary Review 18, No. 4 (Summer 1975).

- Nikos Kazantzakis Research: The Structure of Greek Nationalism and Literature and Philosophy as a Prescription, by Kohsuke Fukuda, Shoraisha, 2024.

- History of Russian Literature (Ιστορία της Ρωσικής ΛογοτεχνίαςGreek, Modern, 1930), partial translation (Preface - Chapter 10) by Kohsuke Fukuda, Eastern Christian Studies, 2022.

5.8. Translations by Kazantzakis

Nikos Kazantzakis translated several significant works from other languages into Modern Greek, demonstrating his breadth of literary and intellectual interests.

- Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche

- On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

- Iliad by Homer (translated with Ioannis Kakridis)

- Odyssey by Homer

5.9. Untranslated Works

Several of Nikos Kazantzakis's original works remain untranslated into English, reflecting the vastness of his complete oeuvre.

- Broken Souls (Σπασμένες ΨυχέςGreek, Modern, Spasmenes Psyches, 1908)

- Tertsines (1932-1937, first edition 1960)

- The Ascent (Ο ΑνήφοροςGreek, Modern, O Aniforos, 1946, first edition 2022)

- Mediterranean Journey (Μεσογειακά ΤαξίδιαGreek, Modern)