1. Overview

Cyprus is an island country situated in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, geographically in Western Asia but with strong cultural and geopolitical ties to Southeast Europe. It is the third largest and third most populous island in the Mediterranean. The island has a rich and complex history, having been settled by hunter-gatherers around 13,000 years ago and subsequently influenced by numerous civilizations, including Mycenaean Greeks, Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Romans, Byzantines, Lusignans, Venetians, and Ottomans, before becoming a British colony. Cyprus gained independence in 1960, establishing a bi-communal republic. However, inter-communal tensions and violence between the Greek Cypriot majority and the Turkish Cypriot minority led to a constitutional breakdown and, in 1974, a coup d'état instigated by the Greek military junta followed by a Turkish invasion. This resulted in the de facto partition of the island, with the northern third now administered by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), recognized only by Turkey. The division remains a central political and social issue, with ongoing UN-led efforts for reunification facing significant challenges. Cyprus joined the European Union in 2004, with EU law suspended in the northern part of the island. The country has an advanced, high-income economy, primarily based on services like tourism and finance, but has also faced economic challenges, including a financial crisis in 2012-2013. Recent discoveries of offshore natural gas reserves hold potential for economic development but also contribute to regional geopolitical complexities. The island's culture is a blend of Greek, Turkish, and broader Mediterranean influences, evident in its arts, music, cuisine, and social customs. Human rights issues, particularly those related to the division, such as missing persons, property rights, and freedom of movement, remain significant concerns.

2. Etymology

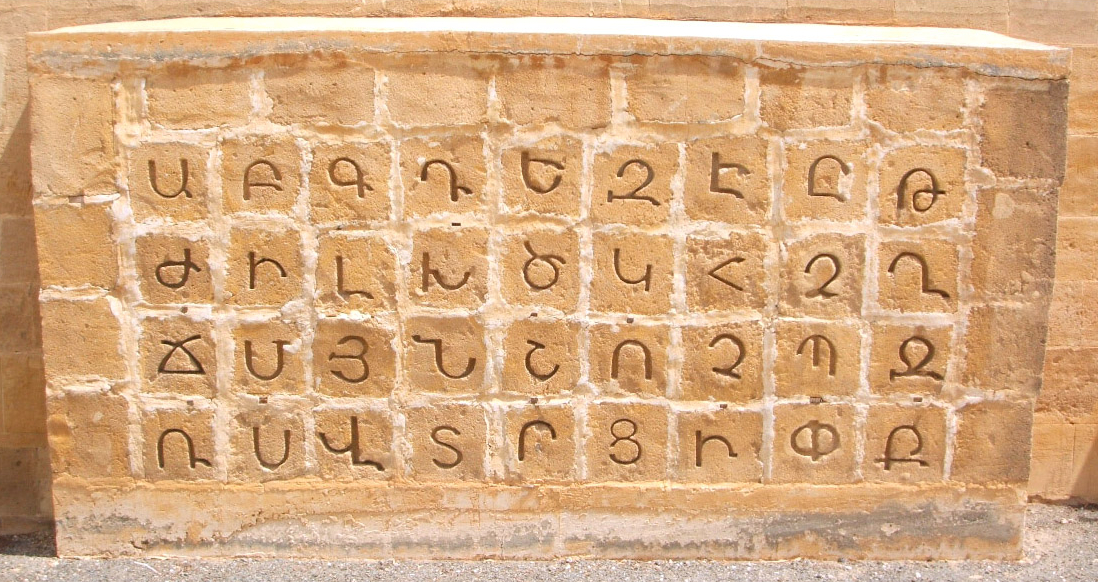

The earliest attested reference to 'Cyprus' is the 15th century BC Mycenaean Greek 𐀓𐀠𐀪𐀍ku-pi-ri-jogmy, meaning "Cypriot" (Greek: ΚύπριοςKypriosGreek, Ancient), written in Linear B syllabic script. The classical Greek form of the name is ΚύπροςKýprosGreek, Ancient.

The etymology of the name 'Cyprus' is unknown, though several theories exist. One suggestion is that it derives from the Greek word for the Mediterranean cypress tree (Cupressus sempervirens), κυπάρισσοςkypárissosGreek, Ancient. Another theory links it to the Greek name of the henna tree (Lawsonia alba), κύπροςkýprosGreek, Ancient.

[[File:Geology of Cyprus-SkiriotissaMine.jpg|thumb|A copper mine in Cyprus. In antiquity, Cyprus was a major source of copper, and its name is linked to the metal.}}

A prominent theory suggests a connection to an Eteocypriot word for copper. This is plausible given the large deposits of copper ore found on the island, which made Cyprus a major source of copper in antiquity. It has been proposed, for example, that the name has roots in the Sumerian word for copper (zubar) or for bronze (kubar).

Through extensive overseas trade, the island gave its name to the Classical Latin word for copper. The phrase aes Cyprium, meaning "metal of Cyprus", was later shortened to Cuprum, which is the root of the English word "copper" and the chemical symbol for copper (Cu).

The standard demonym relating to Cyprus or its people or culture is Cypriot. The terms Cypriote and Cyprian (the latter also becoming a personal name) are also used, though less frequently.

The state's official name in Greek literally translates to "Cypriot Republic" in English, but this translation is not officially used; "Republic of Cyprus" is the standard English rendering. In Turkish, the island is known as KıbrısKibrisTurkish.

3. History

Cyprus has a long and varied history, marked by its strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, which made it a crossroads for various civilizations and empires. From early prehistoric settlements to its modern-day division, the island has experienced significant political, social, and cultural transformations. Key periods include its ancient civilizations, rule by major empires, the medieval Crusader kingdoms, Ottoman and British colonial eras, and its turbulent path to independence and subsequent partition.

3.1. Prehistoric and ancient period

The earliest confirmed human activity on Cyprus dates back to around 13,000-12,000 years ago (11,000 to 10,000 BC), with hunter-gatherer sites like Aetokremnos on the south coast and Vretsia Roudias inland providing evidence of these first inhabitants. The arrival of humans coincided with the extinction of the island's native large mammals, such as the 30 in (75 cm) high Cypriot pygmy hippopotamus and the 3.3 ft (1 m) tall Cyprus dwarf elephant. Neolithic farming communities emerged by approximately 8500 BC. Water wells discovered in western Cyprus by archaeologists are believed to be among the oldest in the world, dated between 9,000 and 10,500 years old.

A significant Neolithic find is the burial of an eight-month-old cat with a human body, estimated to be 9,500 years old (7500 BC). This discovery predates ancient Egyptian civilization and significantly pushes back the date of the earliest known feline-human association. The well-preserved Neolithic village of Khirokitia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, dates to approximately 6800 BC.

During the Late Bronze Age, from around 1650 BC, Cyprus, known in contemporary texts wholly or partly as Alashiya, became increasingly connected to the wider Mediterranean world. This was driven by the trade in copper extracted from the Troodos Mountains, which spurred the development of urbanized settlements across the island. Records indicate that Cyprus at this time was ruled by "kings" who corresponded with leaders of other Mediterranean states, such as the pharaohs of the New Kingdom of Egypt, as documented in the Amarna letters. The first recorded name of a Cypriot king is Kushmeshusha, appearing on letters sent to Ugarit in the 13th century BC.

At the end of the Bronze Age, Cyprus experienced two waves of Mycenaean Greek settlement. The first consisted of Mycenaean Greek traders who began visiting around 1400 BC. A more substantial wave of Greek settlement is believed to have occurred following the Late Bronze Age collapse of Mycenaean Greece, from 1100 to 1050 BC. The island's predominantly Greek character dates from this period. Cyprus holds an important place in Greek mythology as the birthplace of Aphrodite and Adonis, and the home of King Cinyras, Teucer, and Pygmalion. Literary evidence also suggests an early Phoenician presence at Kition, which was under Tyrian rule at the beginning of the 10th century BC. Phoenician merchants, believed to come from Tyre, colonized the area and expanded Kition's political influence. After c. 850 BC, sanctuaries at the Kathari site were rebuilt and reused by the Phoenicians.

Cyprus's strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean made it a target for various empires. It was ruled by the Neo-Assyrian Empire for a century starting in 708 BC, followed by a brief period under Egyptian rule, and then Achaemenid Persian rule in 545 BC. The Cypriots, led by Onesilus, king of Salamis, joined other Greek cities in the Ionian Revolt (499 BC) against the Achaemenids. Although the revolt was suppressed, Cyprus maintained a high degree of autonomy and remained culturally inclined towards the Greek world. Throughout Persian rule, Cypriot kings continued to reign, enjoying special privileges and a semi-autonomous status, though they were considered vassal subjects of the Great King. Rebellions were typically crushed by Persian rulers from Asia Minor, rather than a permanently stationed Persian satrap on the island.

The island was conquered by Alexander the Great in 333 BC. The Cypriot navy aided Alexander during the siege of Tyre and was also sent to assist Admiral Amphoterus. Alexander had two Cypriot generals, Stasander and Stasanor, both from Soli, who later became satraps in his empire.

Following Alexander's death and the subsequent Wars of the Diadochi, Cyprus became part of the Hellenistic empire of Ptolemaic Egypt. During this period, the island was fully Hellenised. In 58 BC, Cyprus was acquired by the Roman Republic. It became the Roman province of Cyprus in 22 BC. While a small province, it possessed several notable religious sanctuaries and played a significant role in Eastern Mediterranean trade, particularly in the production and commerce of Cypriot copper. The Roman rule solidified after the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

3.2. Middle Ages

When the Roman Empire was divided in 286 AD, Cyprus became part of the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire, remaining under its rule for approximately 900 years. During this period, the Greek cultural orientation, prominent since antiquity, developed a strong Hellenistic-Christian character that continues to define the Greek Cypriot community.

Beginning in 649, Cyprus endured repeated attacks and raids launched by the Umayyad Caliphate. While many were quick incursions, others were large-scale attacks resulting in significant casualties and the destruction or plunder of wealth. The city of Salamis was destroyed and never rebuilt. Byzantine control remained stronger in the northern coastal regions, while Arab influence was more pronounced in the south. In 688, Emperor Justinian II and Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan signed a treaty establishing Cyprus as a condominium, whereby the island paid an equal amount of tribute to the Caliphate and tax to the Empire, remaining politically neutral to both but administered as an imperial province. No Byzantine churches from this period survive, and the island entered a period of impoverishment. Full Byzantine rule was restored in 965 when Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas achieved decisive victories on land and sea.

In 1156, Raynald of Châtillon and Thoros II of Armenia brutally sacked Cyprus over three weeks, plundering extensively and capturing leading citizens for ransom, leaving the island devastated for generations. Several Greek priests were mutilated and sent to Constantinople.

In 1185, Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus, a Byzantine imperial family member, seized control of Cyprus and declared it independent. During the Third Crusade in 1191, Richard I of England captured the island from Isaac, using it as a vital supply base relatively safe from Saracen attacks. A year later, Richard sold Cyprus to the Knights Templar. Following a bloody revolt, the Templars sold it to Guy of Lusignan. Guy's brother and successor, Aimery of Cyprus, was recognized as King of Cyprus by Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor.

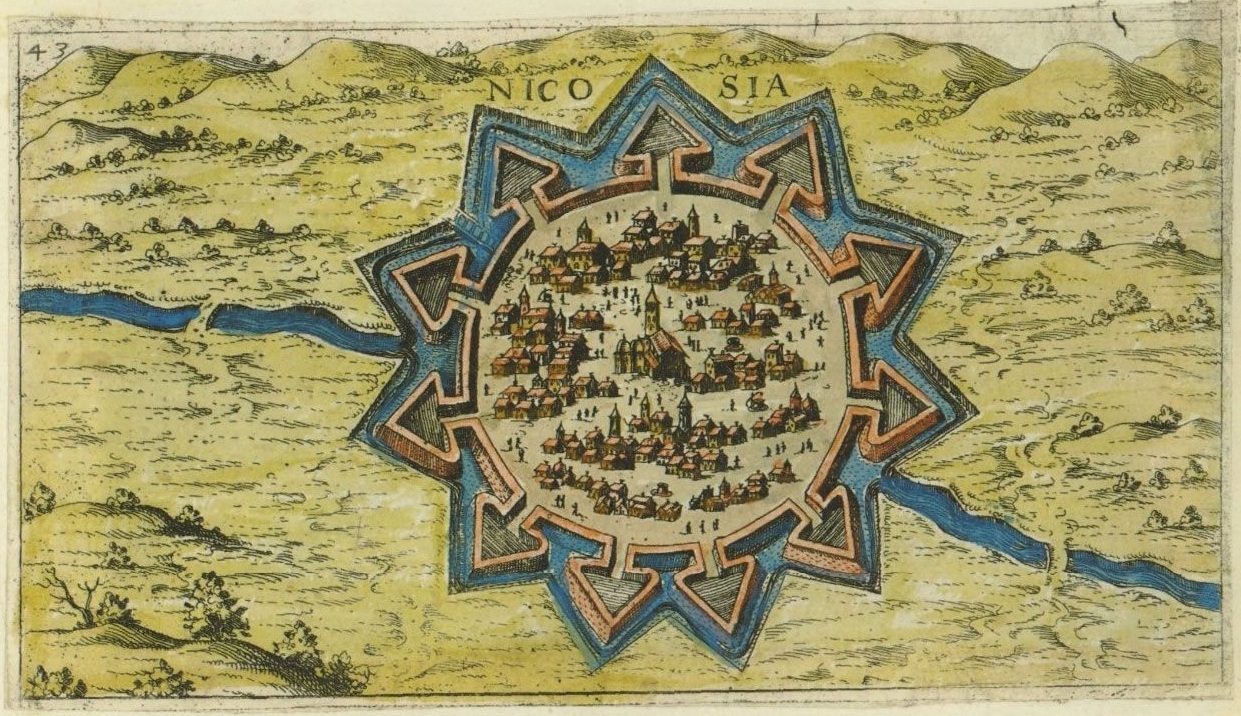

The Lusignan dynasty ruled Cyprus for nearly 300 years. After the death of James II of Cyprus, the last Lusignan king, in 1473, the Republic of Venice assumed control. The king's Venetian widow, Queen Catherine Cornaro, reigned as a figurehead until Venice formally annexed the Kingdom of Cyprus in 1489 following her abdication. The Venetians fortified Nicosia with the Walls of Nicosia and utilized the island as an important commercial hub. Throughout Venetian rule, the Ottoman Empire frequently raided Cyprus. In 1539, the Ottomans destroyed Limassol, prompting the Venetians to further fortify Famagusta and Kyrenia.

Although the French Lusignan aristocracy remained the dominant social class during the medieval period, the earlier assumption that Greeks were treated solely as serfs is no longer considered accurate by academics. It is now accepted that this era saw increasing numbers of Greek Cypriots elevated to the upper classes, a growing Greek middle class, and even intermarriage between the Lusignan royal household and Greeks, such as King John II of Cyprus who married Helena Palaiologina.

3.3. Ottoman Cyprus

In 1570, a full-scale Ottoman assault with 60,000 troops brought Cyprus under Ottoman control, despite stiff resistance from the inhabitants of Nicosia and Famagusta. Ottoman forces massacred many Greek and Armenian Christian inhabitants upon capturing the island. The previous Latin elite were destroyed, and a significant demographic shift occurred with the formation of a Muslim community. Soldiers who participated in the conquest settled on the island, and Turkish peasants and craftsmen were brought from Anatolia. This new community also included banished Anatolian tribes, "undesirable" individuals, members of various "troublesome" Muslim sects, and a number of new converts on the island.

The Ottomans abolished the feudal system and applied the millet system, under which non-Muslim peoples were governed by their own religious authorities. In a reversal from Latin rule, the head of the Church of Cyprus was invested as leader of the Greek Cypriot population, acting as a mediator between Christian Greek Cypriots and Ottoman authorities. This status enabled the Church of Cyprus to end the constant encroachments of the Roman Catholic Church. Ottoman rule varied from indifferent to oppressive, depending on the temperaments of sultans and local officials.

The ratio of Muslims to Christians fluctuated. In 1777-78, 47,000 Muslims constituted a majority over the island's 37,000 Christians. By 1872, the island's population had risen to 144,000, comprising 44,000 Muslims and 100,000 Christians. The Muslim population included numerous crypto-Christians, such as the Linobambaki, a crypto-Catholic community that arose due to religious persecution of Catholics by Ottoman authorities; this community would assimilate into the Turkish Cypriot community during British rule.

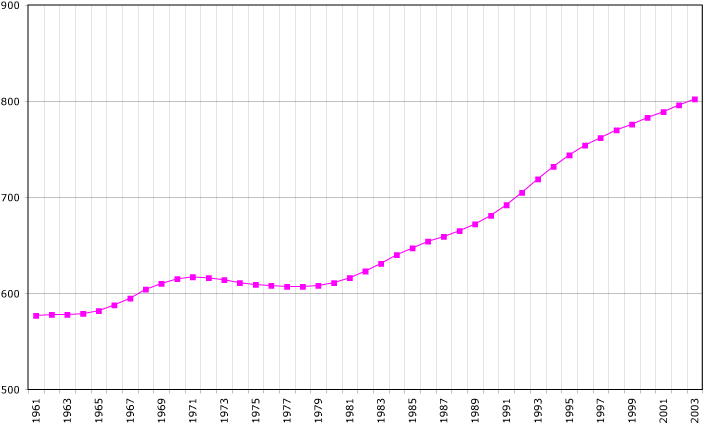

The Greek War of Independence in 1821 saw several Greek Cypriots leave to join Greek forces. In response, the Ottoman governor arrested and executed 486 prominent Greek Cypriots, including Archbishop Kyprianos of Cyprus and four other bishops. In 1828, Greece's first president, Ioannis Kapodistrias, called for Cyprus's union with Greece, and minor uprisings occurred. Centuries of Ottoman neglect, widespread poverty, and tax collectors fueled Greek nationalism. By the 20th century, the idea of enosis (union) with newly independent Greece was firmly rooted among Greek Cypriots. Ottoman misrule led to uprisings by both Greek and Turkish Cypriots, though none succeeded. During Ottoman rule, numeracy, school enrolment, and literacy rates were low, persisting for some time after Ottoman rule ended before rapidly increasing in the twentieth century.

3.4. British Cyprus

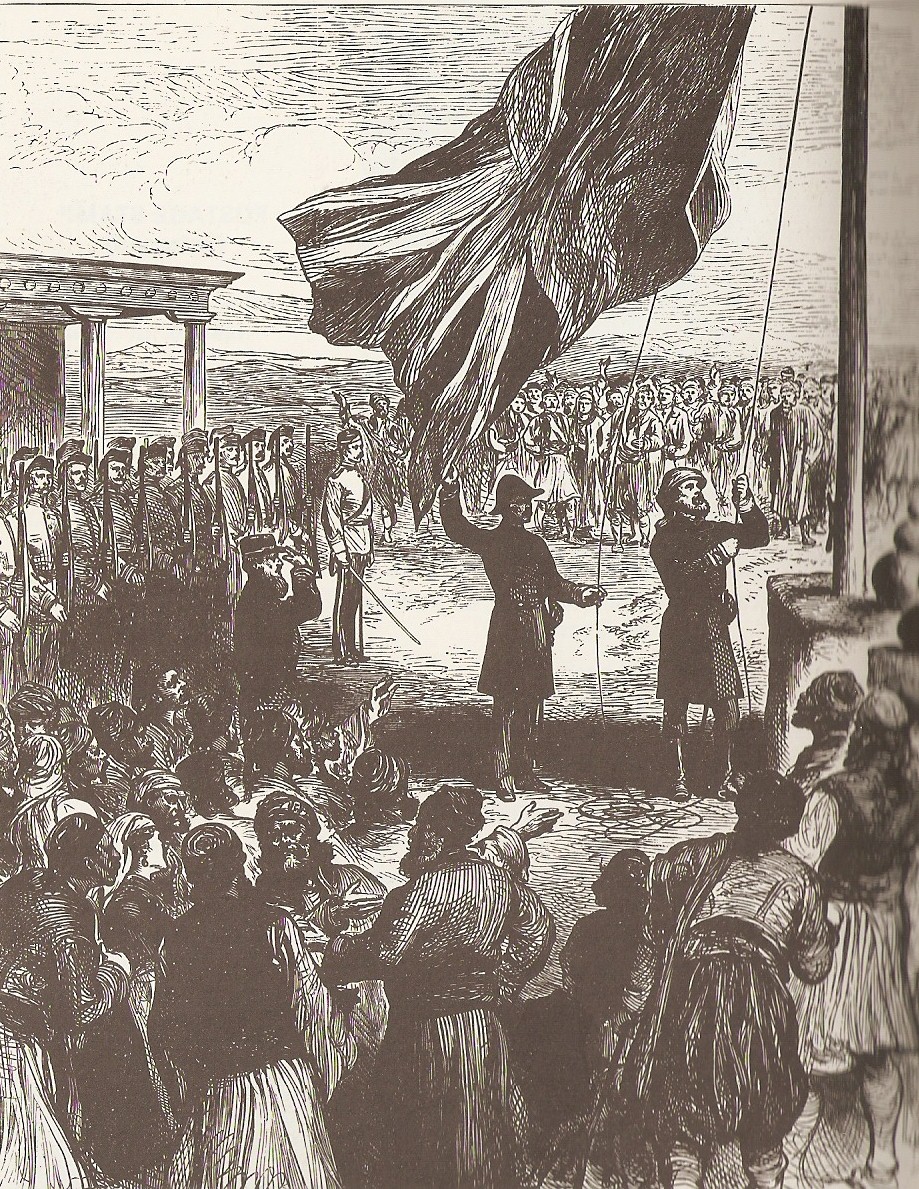

Following the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878) and the Congress of Berlin, Cyprus was leased to the British Empire, which de facto took over its administration in 1878. Sovereignty remained nominally Ottoman until 5 November 1914, when Britain formally annexed Cyprus, along with Egypt and Sudan, after the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in World War I. This was in exchange for guarantees that Britain would use the island as a base to protect the Ottoman Empire against possible Russian aggression.

The island served Britain as a key military base for its colonial routes. By 1906, with the completion of Famagusta harbor, Cyprus became a strategic naval outpost overlooking the Suez Canal, the crucial route to India, then Britain's most important overseas possession.

In October 1915, Britain offered Cyprus to Greece, ruled by King Constantine I of Greece, on the condition that Greece join the war on the side of the British and assist Serbia, fulfilling treaty obligations under the Greek-Serbian Alliance of 1913. This presented Greece with an opportunity to achieve enosis with Cyprus, but the Zaimis administration declined the British proposal.

In 1923, under the Treaty of Lausanne, the nascent Turkish republic relinquished any claim to Cyprus. In 1925, Cyprus was declared a British crown colony. During World War II, many Greek and Turkish Cypriots enlisted in the Cyprus Regiment.

The Greek Cypriot population hoped British administration would lead to enosis. This idea was historically part of the Megali Idea, a broader Greek political ambition to encompass territories with large Greek populations in the former Ottoman Empire. It was actively pursued by the Cypriot Orthodox Church, whose members were often educated in Greece. These religious officials, along with Greek military officers and professionals, later founded the guerrilla organization EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston, National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters). Greek Cypriots viewed the island as historically Greek and believed union with Greece was a natural right. In the 1950s, enosis became part of Greek national policy.

Initially, Turkish Cypriots favored continued British rule. However, they were alarmed by Greek Cypriot calls for enosis, viewing the union of the Cretan State with Greece (which led to the exodus of Cretan Turks) as a precedent to avoid. They adopted a pro-partition stance (taksim) in response to EOKA's militant activity. Turkish Cypriots saw themselves as a distinct ethnic group with a separate right to self-determination. In the 1950s, Turkish leader Adnan Menderes considered Cyprus an "extension of Anatolia," initially rejecting partition and favoring annexation of the whole island to Turkey. Realizing the Turkish Cypriot population (only 20%) made annexation unfeasible, Turkish national policy shifted to favor partition. The slogan "Partition or Death" was frequently used in Turkish Cypriot and Turkish protests.

In January 1950, the Church of Cyprus organized a referendum (supervised by clerics, without Turkish Cypriot participation), where 96% of participating Greek Cypriots voted for enosis. At the time, Greeks constituted 80.2% of the island's population (1946 census). The British administration proposed restricted autonomy under a constitution, but it was rejected. In 1955, EOKA was founded, seeking union with Greece through armed struggle. Simultaneously, the Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT), calling for taksim, was established by Turkish Cypriots. British officials reportedly tolerated TMT's creation, with the Secretary of State for the Colonies advising the Governor of Cyprus in July 1958 not to act against TMT despite its illegal actions, to avoid harming British relations with the Turkish government.

3.5. Independence and inter-communal violence

Cyprus was granted independence in 1960, following an armed campaign primarily led by the Greek Cypriot nationalist organization EOKA. The future of the island had become a point of contention between its two prominent ethnic communities: the Greek Cypriots, who constituted 77% of the population in 1960, and the Turkish Cypriots, who made up 18%. From the 19th century, the Greek Cypriot population pursued enosis (union with Greece), a policy that Greece itself adopted in the 1950s. Conversely, the Turkish Cypriot population initially favored continued British rule but later, with Turkey's backing, advocated for taksim (partition of the island and creation of a Turkish polity in the north).

Under the Zürich and London Agreement, Cyprus officially became independent on 16 August 1960. At the time, the total population was 573,566, comprising 442,138 (77.1%) Greeks, 104,320 (18.2%) Turks, and 27,108 (4.7%) others. The UK retained two Sovereign Base Areas, Akrotiri and Dhekelia. Government posts and public offices were allocated by ethnic quotas, granting the Turkish Cypriot minority a permanent veto, 30% representation in parliament and administration, and recognizing Greece, Turkey, and the UK as guarantor powers.

However, the power-sharing arrangements soon led to legal impasses and discontent on both sides. Nationalist militants resumed training, supported by Greece and Turkey respectively. The Greek Cypriot leadership, believing the rights granted to Turkish Cypriots under the 1960 constitution were excessive, formulated the Akritas plan. This plan aimed to reform the constitution in favor of Greek Cypriots, persuade the international community of the changes' correctness, and, if necessary, violently subjugate Turkish Cypriots who did not accept the plan. Tensions escalated when President Archbishop Makarios III proposed thirteen constitutional amendments, which were rejected by Turkey and opposed by Turkish Cypriots.

Intercommunal violence erupted on 21 December 1963 (an event known as Bloody Christmas), when two Turkish Cypriots were killed in an incident involving Greek Cypriot police. The ensuing violence resulted in the deaths of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots, the destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages, and the displacement of 25,000-30,000 Turkish Cypriots into enclaves. This crisis effectively ended Turkish Cypriot participation in the administration, with Turkish Cypriots claiming the government had lost its legitimacy. While some Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from traveling and accessing government buildings, some Turkish Cypriots willingly withdrew following calls from their own administration. The republic's structure was unilaterally changed by Makarios, and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with UNFICYP troops deployed.

In 1964, Turkey threatened to invade Cyprus in response to the ongoing Cypriot intercommunal violence, but this was averted by a strongly worded telegram from US President Lyndon B. Johnson on 5 June, warning that the US would not support Turkey in case of a Soviet invasion of Turkish territory. By this time, enosis was official Greek policy. Makarios and Greek Prime Minister Georgios Papandreou agreed enosis should be the ultimate aim, and King Constantine II of Greece wished Cyprus "a speedy union with the mother country." Greece dispatched 10,000 troops to Cyprus to counter a possible Turkish invasion. The 1963-64 crisis deepened the divide, leading to the displacement of Turkish Cypriots and the end of their representation in the republic.

3.6. 1974 coup d'état, invasion, and division

On 15 July 1974, the Greek military junta under Dimitrios Ioannides instigated a coup d'état in Cyprus, aiming to unite the island with Greece. The coup ousted President Makarios III and installed pro-enosis nationalist Nikos Sampson in his place.

In response to the coup, Turkey launched the Turkish invasion on 20 July 1974, citing its right to intervene under the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee to restore constitutional order. This justification has been rejected by the United Nations and the international community.

The Turkish air force bombed Greek positions, and hundreds of paratroopers were dropped between Nicosia and Kyrenia, where well-armed Turkish Cypriot enclaves had long been established. Off the Kyrenia coast, Turkish troop ships landed 6,000 men, tanks, trucks, and armored vehicles.

After a ceasefire was agreed upon three days later, Turkey had landed 30,000 troops and captured Kyrenia, the corridor linking Kyrenia to Nicosia, and the Turkish Cypriot quarter of Nicosia itself. The junta in Athens and the Sampson regime in Cyprus subsequently fell from power. In Nicosia, Glafkos Clerides temporarily assumed the presidency. However, following peace negotiations in Geneva, the Turkish government reinforced its Kyrenia bridgehead and launched a second invasion on 14 August. This second offensive resulted in the capture of Morphou, the Karpass Peninsula, Famagusta, and the Mesaoria plain.

International pressure led to another ceasefire. By then, 36% of the island had been taken over by Turkish forces, and over 150,000 Greek Cypriots had been evicted from their homes in the north. Concurrently, around 50,000 Turkish Cypriots were displaced to the north and settled in the properties of the displaced Greek Cypriots. The United States Congress imposed an arms embargo on Turkey in mid-1975 for using US-supplied equipment during the invasion.

The conflict resulted in 1,534 Greek Cypriots and 502 Turkish Cypriots being listed as missing from the fighting between 1963 and 1974.

The Republic of Cyprus holds de jure sovereignty over the entire island, including its territorial waters and exclusive economic zone, except for the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, which remain under UK control. However, the Republic of Cyprus is de facto partitioned. The area under its effective control, in the south and west, comprises about 59% of the island's area. The north, covering about 36% of the island, is administered by the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). A UN buffer zone covers another 4%. The international community considers the northern part of the island to be territory of the Republic of Cyprus occupied by Turkish forces. This occupation is viewed as illegal under international law and, since Cyprus joined the European Union, as an illegal occupation of EU territory.

3.7. Post-division

Following the restoration of constitutional order and the return of Archbishop Makarios III to Cyprus in December 1974, Turkish troops remained, occupying the northeastern portion of the island. In 1983, the Turkish Cypriot parliament, led by Turkish Cypriot leader Rauf Denktaş, proclaimed the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). This entity is recognized only by Turkey.

The events of the summer of 1974 continue to dominate the politics on the island and Greco-Turkish relations. Turkish settlers have been moved to the north with the encouragement of the Turkish and Turkish Cypriot states. The Republic of Cyprus considers their presence a violation of the Geneva Convention. Many Turkish settlers have since severed ties with Turkey, and their second generation considers Cyprus their homeland.

The Turkish invasion, subsequent occupation, and the TRNC's declaration of independence have been condemned by United Nations resolutions, which are reaffirmed by the Security Council annually. Human rights issues stemming from the division, such as the plight of missing persons from both communities and the unresolved property rights of displaced individuals, remain critical concerns. UNFICYP (United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus) has maintained a presence on the island since 1964, monitoring the ceasefire lines and working to maintain peace.

3.8. 21st century

Attempts to resolve the Cyprus dispute have continued into the 21st century. In 2004, the Annan Plan, drafted by then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, was put to a referendum in both Cypriot administrations. While 65% of Turkish Cypriots voted in support of the plan, 74% of Greek Cypriots voted against it, citing concerns that it disproportionately favored Turkish Cypriots and granted unreasonable influence to Turkey. In total, 66.7% of voters rejected the Annan Plan.

On 1 May 2004, Cyprus joined the European Union along with nine other countries. Cyprus was accepted into the EU as a whole, although EU legislation is suspended in Northern Cyprus pending a final settlement of the Cyprus problem.

Efforts have been made to enhance freedom of movement between the two sides. In April 2003, Northern Cyprus unilaterally eased checkpoint restrictions, permitting Cypriots to cross between the two sides for the first time in 30 years. In March 2008, a wall that had stood for decades at the boundary between the Republic of Cyprus and the UN buffer zone in Nicosia was demolished. This wall had cut across Ledra Street in the heart of the capital and was a strong symbol of the island's 32-year division. On 3 April 2008, Ledra Street was reopened in the presence of Greek and Turkish Cypriot officials.

Reunification talks were relaunched in 2015 but collapsed in 2017. The human rights implications of the division, including issues related to missing persons, property rights, and freedom of movement, continue to be significant.

In February 2019, the European Union warned that Cyprus was selling EU passports to Russian oligarchs, potentially allowing organized crime syndicates to infiltrate the EU. In 2020, leaked documents revealed a wider range of former and current officials from various countries who had bought Cypriot citizenship prior to a change in the law in July 2019. This "golden passport" scheme raised concerns about corruption and its social impact. The scheme was subsequently terminated.

Cyprus has also faced a financial crisis, particularly in 2012-2013, linked to the Greek debt crisis, which required an international bailout and imposed hardships on the population. Recent economic developments include the exploration of offshore natural gas reserves, which have potential economic benefits but also contribute to geopolitical tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly with Turkey regarding maritime disputes.

In November 2023, the Cyprus Confidential data leak, published by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, showed the country's financial network entertaining strong links with Russian oligarchs and high-ranking figures in the Kremlin, supporting the regime of Vladimir Putin. This again highlighted issues of governance and the social impact of such financial dealings.

In July 2024, on the 50th anniversary of the Turkish invasion, Turkish President Erdoğan rejected a United Nations-endorsed plan for a federal government and supported the idea of two separate states in Cyprus. Greek Cypriots immediately rejected Erdoğan's two-state proposal, calling it a "non-starter," underscoring the continued deep divisions and challenges to a lasting peace.

4. Geography

Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily and Sardinia, in terms of both area and population. It is also the world's 80th largest island by area and 51st largest by population. It is located in the eastern Mediterranean, south of Turkey, west of Syria and Lebanon, northwest of Israel and Palestine, and north of Egypt. Its capital and largest city is Nicosia.

4.1. Topography

The physical relief of Cyprus is dominated by two main mountain ranges and the central plain they encompass. The Troodos Mountains cover most of the southern and western portions of the island, accounting for roughly half its area. The highest point on Cyprus is Mount Olympus at 6.4 K ft (1.95 K m), located in the center of the Troodos range. This range is primarily composed of ophiolite, a section of ancient oceanic crust.

The smaller Kyrenia Range, a narrow limestone mountain chain, extends along the northern coastline. It occupies substantially less area, and its elevations are lower, reaching a maximum of 3.3 K ft (1.02 K m).

Between these two mountain ranges lies the central Mesaoria plain. This plain is drained by the Pedieos River, the longest river on the island, which flows through Nicosia. Other significant rivers include the Yialias and the Serakhis. Most rivers are seasonal, flowing mainly in the winter rainy season.

The coastline of Cyprus is varied, featuring rocky headlands, sandy beaches, and numerous coves. The Cape Greco area in the southeast is known for its sea caves. The island lies within the Anatolian Plate.

4.2. Climate

Cyprus has a subtropical climate of the Mediterranean and semi-arid type (in the northeastern part of the island), corresponding to Köppen climate classifications Csa and BSh. It experiences very mild winters, particularly on the coast, and warm to hot summers. Snowfall is generally confined to the Troodos Mountains in the central part of the island.

Rainfall occurs mainly in winter, with summers being generally dry. Cyprus has one of the warmest climates in the Mediterranean part of the European Union. The average annual temperature on the coast is around 75.2 °F (24 °C) during the day and 57.2 °F (14 °C) at night. Generally, summers last about eight months, beginning in April with average temperatures of 69.8 °F (21 °C) to 73.4 °F (23 °C) during the day and 51.8 °F (11 °C) to 55.4 °F (13 °C) at night. Summer ends in November with average temperatures of 71.6 °F (22 °C) to 73.4 °F (23 °C) during the day and 53.6 °F (12 °C) to 57.2 °F (14 °C) at night, although in the remaining four months, temperatures can sometimes exceed 68 °F (20 °C).

Coastal locations in Cyprus receive around 3,200 sunshine hours per year, ranging from an average of 5-6 hours of sunshine per day in December to an average of 12-13 hours in July. This is approximately double that of cities in the northern half of Europe.

4.3. Water supply

Cyprus faces a chronic shortage of water. The country relies heavily on rainfall to provide household water, but in the past 30 years, average yearly precipitation has decreased. Between 2001 and 2004, exceptionally heavy annual rainfall pushed water reserves up, with supply exceeding demand, allowing total storage in the island's reservoirs to rise to an all-time high by the start of 2005. However, since then, demand has increased annually due to local population growth, an influx of foreigners, and increasing numbers of tourists, while supply has fallen as a result of more frequent droughts.

Dams remain the principal source of water for both domestic and agricultural use. Cyprus has a total of 108 dams and reservoirs, with a total water storage capacity of about 432 M yd3 (330.00 M m3). Water desalination plants are gradually being constructed to deal with recent years of prolonged drought. The government has invested heavily in these plants, which have supplied almost 50 percent of domestic water since 2001. Efforts have also been made to raise public awareness about water conservation and encourage domestic users to take more responsibility for this increasingly scarce commodity.

Turkey has constructed a water pipeline under the Mediterranean Sea from Anamur on its southern coast to the northern coast of Cyprus, to supply Northern Cyprus with potable and irrigation water (see Northern Cyprus Water Supply Project).

4.4. Flora and fauna

Cyprus is home to a number of endemic species. Notable among these are the Cypriot mouse (Mus cypriacus), the golden oak (a species of oak tree), and the Cyprus cedar. The island also hosts the Cyprus Mediterranean forests ecoregion. The Cyprus mouflon, a wild sheep, is the national animal and is found in the Troodos Mountains. Birdlife is rich, particularly during migration seasons, as Cyprus lies on a major migratory route between Europe, Asia, and Africa. Sea turtles, including the green turtle and loggerhead turtle, nest on some of its beaches. The flora includes over 1,900 species and subspecies of flowering plants, of which around 140 are endemic.

5. Government and politics

The Republic of Cyprus is a presidential republic. The political system is framed by the 1960 Constitution, which established a power-sharing arrangement between the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities. However, following the inter-communal violence of 1963-64 and the de facto partition of the island in 1974, the government operates in the areas effectively controlled by the Republic, which is the southern two-thirds of the island. The human rights implications of the division significantly impact the political landscape.

5.1. Government structure

The head of state and government is the President, elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term. Executive power is exercised by the President and the Council of Ministers, which is appointed by the President.

Legislative power is vested in the House of Representatives (Vouli Antiprosopon). Members are elected for a five-year term. Under the 1960 Constitution, 56 seats are allocated to Greek Cypriots and 24 to Turkish Cypriots. However, since 1964, the Turkish Cypriot seats have remained vacant. Three additional observer seats represent the Armenian, Latin, and Maronite minorities. The judiciary is independent of both the executive and the legislature, headed by the Supreme Court.

The 1960 Constitution envisaged a complex system of checks and balances. The executive was to be led by a Greek Cypriot president and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president, each elected by their respective communities and possessing veto rights over certain legislation and executive decisions. This system broke down after the 1963-64 crisis.

The political environment is characterized by several major parties, including the conservative Democratic Rally (DISY), the communist Progressive Party of Working People (AKEL), the centrist Democratic Party (DIKO), and the social-democratic Movement for Social Democracy (EDEK).

In 2008, Dimitris Christofias of AKEL became the country's first communist head of state. Nicos Anastasiades of DISY served as president from 2013 to 2023. As of February 2023, Nikos Christodoulides, an independent supported by centrist parties, is the President of Cyprus.

5.2. Administrative divisions

The Republic of Cyprus is divided into six districts (επαρχίεςeparchiesGreek, Modern, singular επαρχίαeparchiaGreek, Modern; kazalarkazalarTurkish, singular kazakazaTurkish). These are:

- Nicosia (ΛευκωσίαLefkosiaGreek, Modern; LefkoşaTurkish)

- Famagusta (ΑμμόχωστοςAmmochostosGreek, Modern; GazimağusaTurkish)

- Kyrenia (ΚερύνειαKeryneiaGreek, Modern; GirneTurkish)

- Larnaca (ΛάρνακαLarnakaGreek, Modern; LarnakaTurkish)

- Limassol (ΛεμεσόςLemesosGreek, Modern; LimasolTurkish)

- Paphos (ΠάφοςPafosGreek, Modern; BafTurkish)

The island's division has practical implications for administration. The Kyrenia District, most of the Famagusta District, and parts of the Nicosia and Larnaca Districts are under the control of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The capital, Nicosia, is divided, with the northern part serving as the capital of the TRNC.

5.3. Exclaves and enclaves

Cyprus has four exclaves, all located within the territory of the British Sovereign Base Area of Dhekelia. The first two are the villages of Ormidhia and Xylotymvou. The third is the Dhekelia Power Station, which is divided by a British road into two parts. The northern part is the EAC refugee settlement. The southern part, although located by the sea, is also an exclave because it has no territorial waters of its own; these are UK waters.

The UN buffer zone (Green Line) runs up against Dhekelia and resumes from its eastern side off Ayios Nikolaos, connected to the rest of Dhekelia by a thin land corridor. In this sense, the buffer zone effectively turns the Paralimni area, on the southeast corner of the island, into a de facto, though not de jure, exclave. These unique territorial arrangements contribute to the complexities of the island's administration and the lives of its inhabitants.

5.4. Foreign relations

The Republic of Cyprus is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU) (since 2004), the Commonwealth of Nations, the Council of Europe, the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). It was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement but left upon joining the EU.

Cyprus's foreign policy is significantly shaped by the Cyprus dispute. The primary foreign policy objective is to achieve a just and viable solution to the division of the island, based on UN resolutions and EU principles. This includes the withdrawal of Turkish troops, the termination of the Turkish settlement policy, and the restoration of the human rights of all Cypriots, including refugees.

Key bilateral relationships include those with Greece, which is a close ally due to shared cultural and historical ties, and Turkey, with which relations are strained due to the ongoing occupation of Northern Cyprus. The United Kingdom, as a former colonial power and a guarantor power under the 1960 treaties, also plays a significant role. Cyprus maintains good relations with other EU member states, the United States, Russia, and countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

Cyprus is involved in regional cooperation initiatives in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly concerning energy security following the discovery of offshore natural gas reserves. These discoveries have also led to increased geopolitical tensions, especially maritime disputes with Turkey over Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) delimitations. The country actively participates in the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). Cyprus has long maintained good relations with NATO while not being a member, but in 2024 confirmed its intention to officially join the alliance.

5.5. Military

The Cypriot National Guard (Εθνική ΦρουράEthnikí FrouráGreek, Modern) is the main military institution of the Republic of Cyprus. It is a combined arms force with land, air, and naval elements. Its primary mission is the defense of the Republic's territory and sovereignty.

Historically, all male citizens were required to serve 24 months in the National Guard after their 17th birthday. In 2016, this period of compulsory military service was reduced to 14 months. Approximately 10,000 persons are trained annually in recruit centers. Depending on their awarded specialty, conscript recruits are then transferred to specialty training camps or operational units.

While the armed forces were mainly conscript-based until 2016, a large professional enlisted institution (ΣΥΟΠ - S контрактники (SYOP)) has since been adopted. This, combined with the reduction of conscript service, produces an approximate 3:1 ratio between conscript and professional enlisted personnel.

The military context of the island is heavily influenced by its division. Turkish military forces are stationed in Northern Cyprus. UNFICYP, the UN peacekeeping force, maintains a presence in the buffer zone separating the two parts of the island. Greece also maintains a military contingent in Cyprus (ELDYK) as per the Treaty of Alliance. The presence of foreign forces and the ongoing political situation contribute to a militarized environment, particularly along the Green Line.

5.6. Law, justice and human rights

The Cypriot legal system is primarily based on common law and equity, with influences from civil law in certain areas. The Constitution of Cyprus is the supreme law of the land. The judiciary is independent, with the Supreme Court of Cyprus at its apex.

The Cyprus Police (Αστυνομία ΚύπρουAstynomía KýprouGreek, Modern, Kıbrıs PolisiTurkish) is the national police service of the Republic and has been under the Ministry of Justice and Public Order since 1993.

Human rights are generally respected in the Republic of Cyprus. However, significant human rights issues persist, largely stemming from the island's division. These include:

- Freedom of movement:** Restrictions on movement between the northern and southern parts of the island affect all Cypriots, although some crossing points have opened since 2003.

- Missing persons:** The fate of hundreds of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots missing since the inter-communal violence of 1963-64 and the 1974 invasion remains a deeply painful issue for their families and a major human rights concern. The Committee on Missing Persons in Cyprus (CMP) continues its work to locate, identify, and return remains.

- Property rights:** The displacement of populations in 1974 resulted in widespread loss of property. The rights of displaced persons to their properties in both parts of the island are a contentious issue, with numerous cases brought before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

- Discrimination:** There are concerns about discrimination against minority groups and migrants.

- Human trafficking:** Cyprus has been identified as a destination and transit country for human trafficking, particularly for sexual exploitation and forced labor. The government has taken steps to combat trafficking, but challenges remain.

- Freedom of the press:** While generally free, there have been occasional concerns regarding pressure on journalists or media outlets.

The ECtHR has issued several judgments against Turkey concerning human rights violations in Cyprus stemming from the 1974 invasion and continued occupation, including violations of property rights, rights of displaced persons, and the rights of relatives of missing persons. In 2014, Turkey was ordered to pay significant compensation to Cyprus for the invasion, a judgment Ankara announced it would ignore. The destruction of Greek and Christian heritage in the north, including looting, deliberate destruction of churches, and alteration of historical site names, has also been documented and condemned by international bodies. Conversely, some Turkish Cypriot heritage sites in the south have also suffered neglect or damage.

6. Economy

Cyprus has an advanced, high-income economy with a strong service sector. The economy experienced significant growth in the decades following independence, particularly after aligning with the European Union. However, it has also faced challenges, including the impact of the island's division and the 2012-2013 financial crisis. Social aspects, such as the impact of economic policies on vulnerable groups and labor rights, are important considerations.

6.1. Economic structure and main industries

The Cypriot economy is predominantly service-based, with this sector contributing the largest share to the GDP and employment. Key industries include:

- Tourism:** Cyprus is a major tourist destination, attracting millions of visitors annually to its beaches, historical sites, and cultural attractions. Tourism is a vital source of foreign exchange and employment.

- Financial services:** The country has developed into an international financial center, offering services such as banking, insurance, and investment funds. Its favorable tax regime has attracted foreign businesses and investment, although this has also led to scrutiny regarding financial transparency and money laundering concerns.

- Shipping:** Cyprus has one of the largest ship registers in the world and a significant maritime industry, including ship management services.

- Real estate and construction:** These sectors have seen considerable activity, partly driven by tourism and foreign investment.

- Agriculture:** While its contribution to GDP has declined, agriculture remains important, producing citrus fruits, potatoes, grapes, olives, and dairy products like halloumi cheese.

- Manufacturing:** This sector is relatively small, focusing on food processing, textiles, footwear, and light industrial goods.

The government has actively sought to attract foreign investment through various incentives. Labor rights are generally protected, with trade unions playing an active role. Environmental impacts of economic activities, particularly tourism and construction, are an ongoing concern. The economy in the northern part of the island is significantly less developed and heavily reliant on Turkey for financial support.

6.2. Financial crisis and recovery

In 2012-2013, Cyprus faced a severe financial crisis. The causes were multifaceted, including the exposure of Cypriot banks to the Greek government-debt crisis, an over-leveraged local banking sector, and a domestic property bubble.

The crisis culminated in March 2013 when Cyprus requested an international bailout. An agreement was reached with the Eurogroup (comprising the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund - the "troika") for a 10.00 B EUR loan. The bailout package included controversial measures:

- The restructuring of the banking sector, including the winding down of Cyprus Popular Bank (Laiki Bank) and the recapitalization of Bank of Cyprus.

- A "bail-in" of bank depositors, where uninsured deposits (those over 100.00 K EUR) in the two largest banks faced a significant "haircut" (conversion into bank equity or write-down). This was an unprecedented measure in the Eurozone crisis and caused considerable social and economic disruption, particularly impacting many foreign depositors who had used Cyprus as an offshore financial center.

- Implementation of austerity measures, including cuts in public spending and structural reforms.

The crisis led to a deep recession, a sharp rise in unemployment, and capital controls to prevent bank runs. However, the Cypriot economy demonstrated resilience and began a recovery process aided by adherence to the bailout program, reforms, and a rebound in tourism. By the late 2010s, Cyprus had exited the bailout program and achieved robust economic growth, though challenges such as high private debt levels and non-performing loans in the banking sector remained. The crisis highlighted vulnerabilities in the Cypriot economic model and prompted efforts towards diversification and strengthening financial regulation.

6.3. Energy resources

Significant quantities of offshore natural gas have been discovered in Cyprus's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the Eastern Mediterranean since the 2010s. The most notable discovery is the Aphrodite gas field in Block 12, located about 109 mile (175 km) south of Limassol. Other exploration blocks have also shown promising results.

These discoveries hold substantial potential economic benefits for Cyprus, including revenue generation, enhanced energy security, and the possibility of becoming a regional energy hub. However, the development and exploitation of these resources are complex and fraught with geopolitical challenges.

Turkey, which does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus's EEZ agreements with its neighbors (Egypt, Lebanon, Israel) and disputes Cyprus's rights to explore for hydrocarbons, has conducted its own drilling activities in waters claimed by Cyprus. This has led to increased tensions in the region, with the EU and other international actors calling on Turkey to respect Cyprus's sovereign rights.

The monetization of the gas reserves involves various options, including pipelines to regional markets (such as Egypt or Europe), or the construction of a Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) plant in Cyprus. Each option presents technical, financial, and geopolitical hurdles. Cyprus is also working on energy interconnections, such as the EuroAsia Interconnector, a proposed undersea power cable to link the electricity grids of Israel, Cyprus, and Greece (Crete), aiming to end Cyprus's energy isolation from the European network.

The energy resources issue is intertwined with the Cyprus dispute, with discussions on how potential revenues might be shared in the event of a reunified island.

6.4. Infrastructure

Cyprus has a well-developed infrastructure, particularly in the government-controlled areas, supporting its economy and society. This includes modern transport networks, telecommunications, and energy facilities, although it remains the last EU member fully isolated from trans-European energy interconnections.

6.4.1. Transport

Cyprus has a modern road network, with vehicles driving on the left-hand side of the road, a legacy of British rule. A series of motorways connects major cities, running along the coast from Paphos to Ayia Napa, with two motorways extending inland to Nicosia (one from Limassol and one from Larnaca). Per capita private car ownership is high.

Public transport primarily consists of bus services, which have been improved and expanded in recent years with new networks implemented in major urban areas and intercity routes. There are no railways in Cyprus; a former government railway ceased operations in 1951.

The main international airports are Larnaca International Airport, which is the busiest, and Paphos International Airport. Nicosia International Airport has been defunct and located within the UN buffer zone since the 1974 Turkish invasion. In Northern Cyprus, Ercan International Airport operates flights, but all international flights must transit through Turkey due to the lack of international recognition of the TRNC.

Major ports are in Limassol and Larnaca, serving cargo, passenger, and cruise ship traffic. These ports are important for Cyprus's role as a transshipment and maritime services hub.

6.4.2. Communications

Telecommunications infrastructure in Cyprus is advanced. CYTA (Cyprus Telecommunications Authority), a state-owned corporation, has historically been the dominant provider of fixed-line telephony, mobile services, and internet access. However, the sector has been liberalized, leading to the emergence of private telecommunications companies such as epic (formerly MTN Cyprus), Cablenet, OTEnet Telecom, Omega Telecom, and PrimeTel. This competition has led to improved services and a variety of options for consumers.

Internet penetration is high, with widespread availability of broadband services, including fiber optic connections in many areas. Mobile telephony is ubiquitous, with extensive 4G and growing 5G coverage. In the areas not controlled by the Republic of Cyprus, mobile phone networks are administered by separate companies, primarily Turkcell and KKTC Telsim. Postal services are reliable and operated by Cyprus Post.

7. Demographics

Cyprus has a diverse demographic profile, shaped by its long history of settlement and migration, and significantly impacted by the political division of the island since 1974. The population comprises mainly Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots, along with several smaller ethnic and religious minority groups and a growing number of foreign residents.

7.1. Population composition

According to the 2021 census conducted by the Republic of Cyprus, the population in the government-controlled areas was 918,100. The CIA World Factbook (2001 estimate for the entire island) indicated Greek Cypriots comprised 77%, Turkish Cypriots 18%, and others 5%.

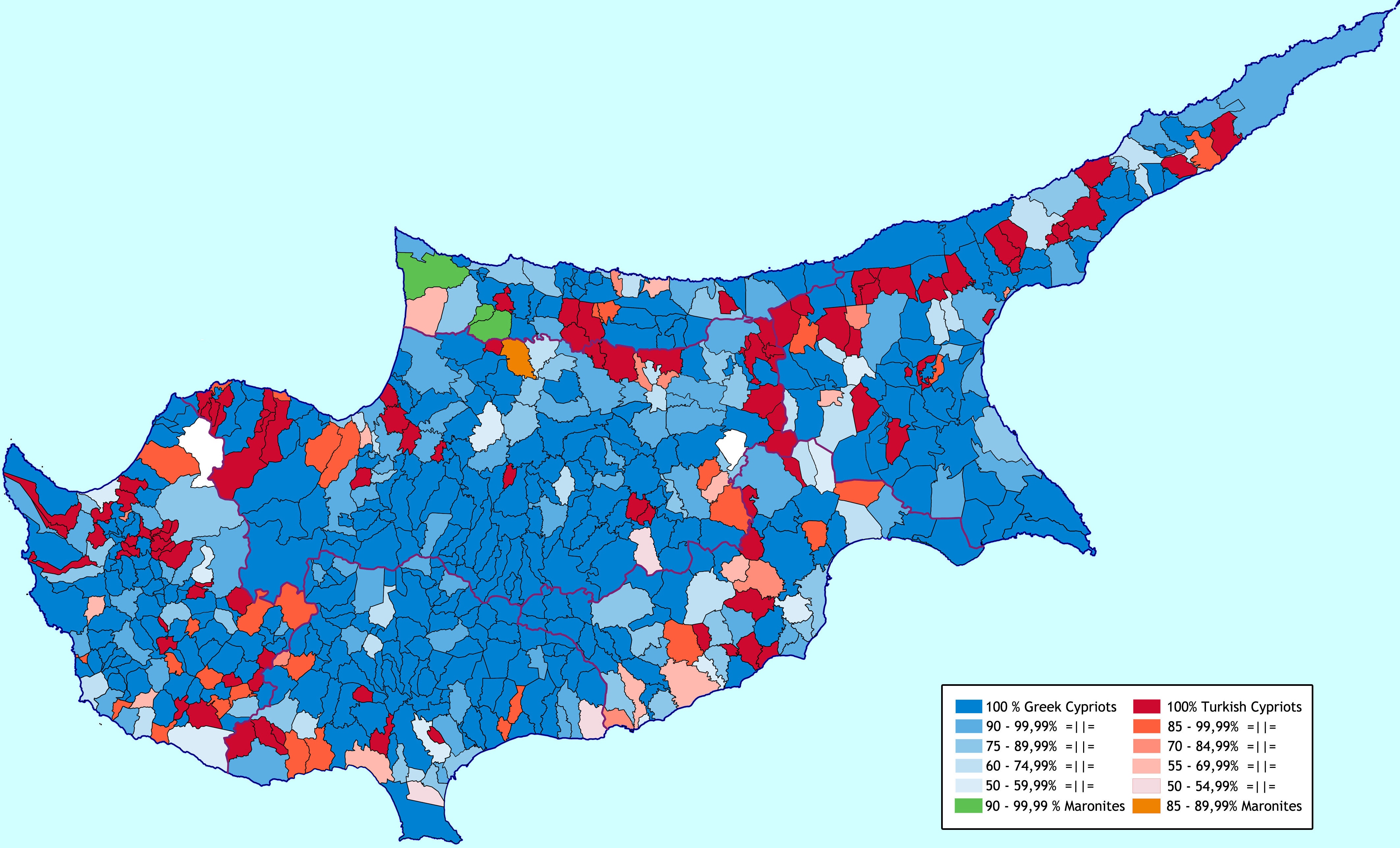

The 1960 census, covering the entire island, recorded a total population of 573,566, of whom 442,138 (77.1%) were Greeks, 104,320 (18.2%) Turks, and 27,108 (4.7%) others (including Armenians, Maronites, and Latins, who are constitutionally recognized minorities).

The 1974 division led to significant population displacement. Subsequent censuses by the Republic of Cyprus excluded the population in the northern areas. The demographic situation in Northern Cyprus is complex due to the influx of settlers from Turkey since 1974, a policy considered illegal by the Republic of Cyprus and the international community. Estimates of the number of these settlers vary, impacting the overall demographic picture of the north. The 2006 census conducted by Northern Cyprus recorded 256,644 people, with a significant portion born in Turkey or having Turkish parentage.

The Republic of Cyprus is also home to a substantial number of foreign residents, including many from other EU countries (notably Greece and the United Kingdom), Russia, and various Asian and Eastern European countries. There is also an issue of undocumented immigrants.

Y-DNA haplogroups found in Cyprus include J (most prevalent), E1b1b, R1 (including R1b), F, I, K, and A, reflecting a complex genetic history with influences from the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe.

The villages of Rizokarpaso (in Northern Cyprus), Potamia (in Nicosia district, government-controlled area), and Pyla (in Larnaca District, within the UN buffer zone) are notable as some of the few remaining settlements with a mixed Greek and Turkish Cypriot population.

| Nationality | Population (2011) |

|---|---|

| Greeks | 29,321 |

| British | 24,046 |

| Romanians | 23,706 |

| Bulgarians | 18,536 |

| Filipinos | 9,413 |

| Russians | 8,164 |

| Sri Lankans | 7,269 |

| Vietnamese | 7,028 |

| Syrians | 3,054 |

| Indians | 2,933 |

7.2. Major cities

The main urban centers in Cyprus are:

- Nicosia** (ΛευκωσίαLefkosiaGreek, Modern; LefkoşaTurkish): The capital and largest city. It is uniquely a divided capital, with the northern part serving as the capital of the TRNC and the southern part as the capital of the Republic of Cyprus. It is the administrative, financial, and cultural heart of the island. The Nicosia Metropolitan area, comprising seven municipalities, is the largest urban agglomeration with a population of approximately 255,309 (2021, government-controlled area).

- Limassol** (ΛεμεσόςLemesosGreek, Modern; LimasolTurkish): The second-largest city, a major port, and a hub for tourism, commerce, and offshore business. It has a vibrant cultural life and a significant expatriate community. Population (municipality): approximately 124,054 (2021).

- Larnaca** (ΛάρνακαLarnakaGreek, Modern; LarnakaTurkish): The third-largest city, home to the island's main international airport and another important port. It is known for its palm-lined seafront and historical sites. Population (municipality): approximately 68,194 (2021).

- Paphos** (ΠάφοςPafosGreek, Modern; BafTurkish): Located on the southwestern coast, Paphos is rich in archaeological sites (a UNESCO World Heritage site) and is a popular tourist destination. It also has an international airport. Population (municipality): approximately 37,297 (2021).

Other significant towns include Strovolos (a large suburb of Nicosia), Famagusta (ΑμμόχωστοςAmmochostosGreek, Modern; GazimağusaTurkish), historically a major port city now in Northern Cyprus and partly a ghost town (Varosha), and Kyrenia (ΚερύνειαKeryneiaGreek, Modern; GirneTurkish), a picturesque harbor town in Northern Cyprus. Population figures for towns in Northern Cyprus are based on TRNC statistics.

7.3. Cypriot diaspora

There is a significant diaspora of both Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots around the world. Large-scale emigration occurred at various points in history, particularly due to economic reasons, colonial rule, and especially after the political turmoil and division of 1974.

The largest Cypriot communities abroad are found in:

- United Kingdom**: Historically a major destination due to colonial ties, the UK hosts a very large Cypriot diaspora, estimated to be several hundred thousand, concentrated mainly in London (particularly in areas like Haringey, Enfield, and Palmers Green). They have established strong community organizations, schools, churches, and mosques.

- Australia**: Australia also has a substantial Cypriot community, primarily in Melbourne and Sydney, which grew significantly after World War II and the 1974 events.

- Canada**: Cypriot immigrants, mainly Greek Cypriots, have settled in cities like Toronto and Montreal.

- United States**: Smaller but notable Cypriot communities exist in the US, particularly in New York (Astoria, Queens) and other urban centers.

- Greece**: Due to close ethnic and cultural ties, many Greek Cypriots have moved to Greece for education, work, or to join family.

- Turkey**: Many Turkish Cypriots have emigrated to Turkey, especially after 1974, for economic and political reasons.

These diaspora communities maintain strong cultural, social, and often political connections to Cyprus, contributing to the island's economy through remittances and investment, and playing a role in advocating for Cypriot causes internationally.

8. Society

Cypriot society is characterized by a blend of Mediterranean traditions and modern European influences. The division of the island has profoundly impacted social structures and interactions, creating distinct yet interconnected communities. Social issues such as human rights, minority integration, and the impact of economic development on social cohesion are prominent.

8.1. Religion

The religious landscape of Cyprus is predominantly divided along ethnic lines. The majority of Greek Cypriots identify as Greek Orthodox Christians (approximately 78% according to Pew Research estimates), adhering to the autocephalous Church of Cyprus. The Church of Cyprus plays a significant historical and social role in the Greek Cypriot community. The first President of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios III, was a prominent religious and political figure.

Most Turkish Cypriots are adherents of Sunni Islam (approximately 20%). Religious practice among Turkish Cypriots varies, with a tradition of secularism influenced by Kemalism from Turkey, though there has been a reported increase in religiosity in recent decades. The Hala Sultan Tekke mosque, near Larnaca Salt Lake, is a highly revered pilgrimage site for Muslims. Other religions comprise about 1% of the population, and about 1% report no religion according to the same estimates.

According to the 2001 census conducted in the government-controlled areas, 94.8% of the population was Eastern Orthodox, 0.9% Armenian Apostolic and Maronite Catholic, 1.5% Roman Catholic, 1.0% Anglican, and 0.6% Muslim. The remaining 1.3% adhered to other religious denominations or did not state their religion. There is also a small Jewish community.

The constitutionally recognized religious groups in the Republic of Cyprus (besides the Church of Cyprus) are the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Maronite Catholic Church, and the Latin Catholic Church. These groups have special rights, including representation in the House of Representatives (as observers) and state funding for their cultural and educational institutions. Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed, though the division of the island has impacted access to religious sites for both communities.

8.2. Languages

Cyprus has two official languages: Greek and Turkish, as stipulated by the 1960 Constitution.

The everyday spoken language of Greek Cypriots is Cypriot Greek, a distinct dialect that differs significantly from Standard Modern Greek in phonology, morphology, syntax, and vocabulary, though they are largely mutually intelligible.

The everyday spoken language of Turkish Cypriots is Cypriot Turkish, a dialect of Turkish that also exhibits unique features influenced by local historical context and contact with Greek.

English is widely spoken, especially in business, tourism, and education. It was the sole official language during British colonial rule (until 1960) and continued to be used de facto in courts of law until 1989 and in legislation until 1996. English features prominently on road signs, public notices, and in advertisements. A high percentage of Cypriots (around 80% in 2010) are proficient in English as a second language.

Recognized minority languages in Cyprus are Armenian and Cypriot Maronite Arabic (also known as Sanna). The government supports these languages through education and cultural initiatives as part of its commitments under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

Russian is also widely spoken among the country's sizeable Russian-speaking community (including immigrants and expatriates from post-Soviet countries) and Pontic Greeks. It is often the third language used on signs in shops and restaurants, particularly in cities like Limassol and Paphos. Other European languages such as French and German are spoken by a smaller percentage of the population.

8.3. Education

Cyprus has a highly developed system of primary and secondary education, offering both public and private schooling. The quality of instruction is generally high, partly attributed to significant public expenditure on education (nearly 7% of GDP, among the highest in the EU).

State schools are generally considered to provide an education equivalent in quality to private-sector institutions. Education is compulsory from pre-primary (age 4 years and 8 months) through lower secondary school (Gymnasium, age 15). Upper secondary education includes Lyceums (general academic) and Technical/Vocational Schools.

For admission to public universities in Cyprus and Greece, students typically take centrally administered entrance examinations. While a state high-school diploma (Apolytirion) is mandatory for university attendance, its grades often account for only a portion of the admission criteria for Cypriot universities, with entrance exam scores being predominant.

Higher education has expanded significantly in recent decades. Cyprus has several public universities, including the University of Cyprus (founded in 1989), the Cyprus University of Technology, and the Open University of Cyprus. There are also numerous private universities and colleges offering a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate programs, attracting both local and international students.

Cypriots have a high rate of tertiary education attainment. In 2019, Cyprus had the highest percentage of citizens of working age with higher-level education in the EU (around 30%), and a very high percentage (around 47%) of its population aged 25-34 had completed tertiary education. Historically, a large majority of Cypriots pursued higher education abroad, primarily in Greece, the United Kingdom, Turkey (for Turkish Cypriots), and other European and North American countries. While this trend continues, the growth of local universities has provided more options domestically.

8.4. Health

Cyprus has a high standard of healthcare, with both public and private sector facilities available. Life expectancy is high, comparable to other developed European countries (around 80 years for males and 84 years for females as of recent estimates).

The public healthcare system was significantly reformed with the introduction of the General Healthcare System (GHS, known locally as GeSY - ΓεΣΥGreek, Modern) in 2019-2020. GeSY aims to provide universal health coverage to the entire population, funded through contributions from employees, employers, the state, and self-employed individuals. It covers a wide range of services, including primary care from personal doctors, specialist outpatient care, hospital care, pharmaceuticals, and laboratory tests.

Prior to GeSY, public healthcare was available at low or no cost to eligible individuals, but many opted for private healthcare due to perceived shorter waiting times and more personalized service. The private healthcare sector remains robust, with numerous private hospitals, clinics, and individual practitioners. Many Cypriots also have private health insurance.

Major public hospitals are located in Nicosia (Nicosia General Hospital, Makario Hospital for mothers and children), Limassol, Larnaca, Paphos, and Famagusta (the new Famagusta General Hospital is in Deryneia, serving the government-controlled part of the district).

Health indicators are generally good. Common health issues are similar to those in other developed nations, including cardiovascular diseases and cancers. The Ministry of Health oversees public health policies, disease prevention, and health promotion campaigns. Access to medical services is generally good across the government-controlled areas. Healthcare in Northern Cyprus is administered separately and faces different challenges, often relying on support from Turkey.

9. Culture

Cypriot culture is a rich tapestry woven from millennia of history and diverse influences, primarily Greek, but also incorporating elements from Anatolian, Levantine, and various European occupiers. While Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots share many cultural traits, distinct religious and linguistic traditions also shape their respective cultural expressions. The division of the island has, in some ways, accentuated these distinctions while also fostering a shared Cypriot identity that transcends the political divide for some.

9.1. Arts

The art history of Cyprus stretches back approximately 10,000 years, evidenced by Chalcolithic period carved figures discovered in villages like Khirokitia and Lempa. The island is renowned for numerous examples of high-quality religious icon painting from the Middle Ages, as well as many painted churches, particularly in the Troodos region (a UNESCO World Heritage site). Cypriot architecture was heavily influenced by French Gothic and Italian Renaissance architecture introduced during the Latin domination era (1191-1571).

A well-known traditional art form dating back at least to the 14th century is Lefkara lace (Lefkaritika), originating from the village of Pano Lefkara. Recognized as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO, Lefkara lace is characterized by distinct design patterns and an intricate, time-consuming production process. Another local art form from Lefkara is Cypriot Filigree (Trifourenio), a type of jewelry made with twisted silver threads.

Modern Cypriot art history begins with painter Vassilis Vryonides (1883-1958), who studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice. The two founding fathers of modern Cypriot art are often considered to be Adamantios Diamantis (1900-1994), who studied at London's Royal College of Art, and Christophoros Savva (1924-1968), who also studied in London at Saint Martin's School of Art. In 1960, Savva, with Welsh artist Glyn Hughes, founded Apophasis, the first independent cultural centre of the newly established Republic of Cyprus. Many Cypriot artists continue to train in England, Greece, or at local institutions like the Cyprus College of Art, University of Nicosia, and the Frederick Institute of Technology.

Figurative painting is prominent in Cypriot art, although conceptual art is promoted by institutions like the Nicosia Municipal Art Centre. Municipal art galleries exist in all main towns, supporting a lively commercial art scene.

Other notable Greek Cypriot artists include Panayiotis Kalorkoti, Nicos Nicolaides, Stass Paraskos, Telemachos Kanthos, and Chris Achilleos. Notable Turkish Cypriot artists include İsmet Güney (designer of the Cyprus flag), Ruzen Atakan, and Mutlu Çerkez.

9.2. Music

The traditional folk music of Cyprus shares elements with Greek, Turkish, and Arabic music, all having roots in Byzantine music. This includes Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot dances such as the tsifteteli (a belly dance) and various circle or line dances like syrtos, kalamatianos, and karsilamas. A form of musical poetry known as chattista (τσιαττιστά) is often performed at traditional feasts and celebrations, involving improvised rhyming verses.

Instruments commonly associated with Cypriot folk music include the violin (fkiolin), lute (laouto), the Cypriot flute (pithkiavlin, a type of fipple flute), oud (outi), kanonaki (a type of zither), and percussion instruments like the toumperleki (a goblet drum) and tamboutsia (frame drum).

Composers associated with traditional Cypriot music include Solon Michaelides, Marios Tokas, Evagoras Karageorgis, and Savvas Salides. Among contemporary musicians, the acclaimed pianist Cyprien Katsaris has Cypriot roots. Composer Andreas G. Orphanides and composer/artistic director Marios Joannou Elia are also notable.

Popular music in Cyprus is heavily influenced by the Greek Laïka (urban folk) and pop scenes. Artists like Anna Vissi, Evridiki, and Michalis Hatzigiannis (who also incorporates Éntekhno rock) have achieved international recognition. The Ayia Napa resort town became known for its urban music scene, supporting hip hop and R&B. In recent years, the reggae scene has grown, with Cypriot artists participating in festivals like Reggae Sunjam. Metal also has a following, with bands such as Armageddon, Blynd, Winter's Verge, and Methysos.

9.3. Literature

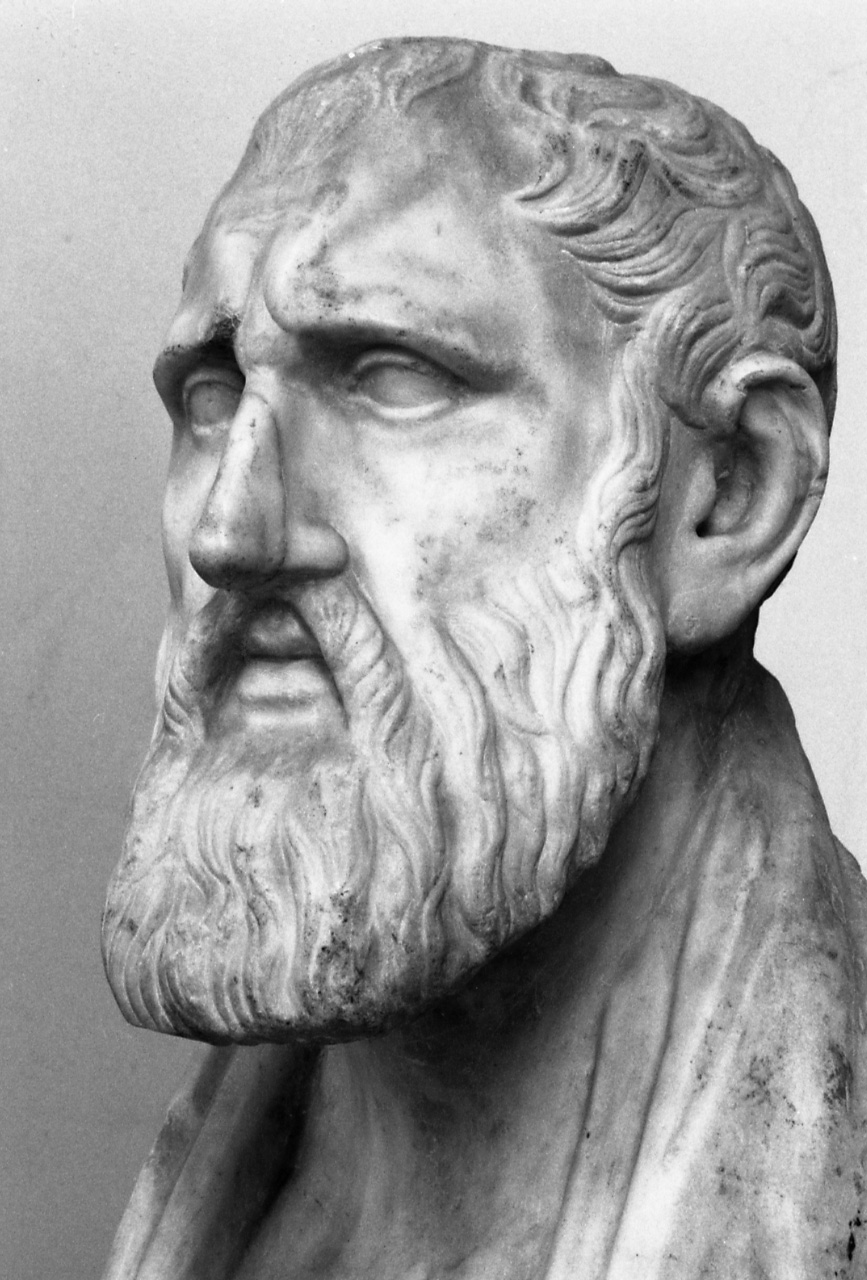

Literary production in Cyprus dates back to antiquity. The Cypria, an epic poem likely composed in the late 7th century BC and attributed to Stasinus, is one of the earliest examples of Greek and European poetry. The Cypriot philosopher Zeno of Citium (c. 334 - c. 262 BC) was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy in Athens.

Epic poetry, notably "acritic songs" (dealing with the exploits of frontier guards of the Byzantine Empire), flourished during the Middle Ages. Two important chronicles, one by Leontios Machairas (covering the period 1359-1432) and another by Georgios Boustronios (covering 1456-1489), document the entire Middle Ages up to the end of Frankish (Lusignan) rule. Poèmes d'amour (love poems) written in medieval Cypriot Greek date back to the 16th century, some of which are translations of works by Petrarch, Bembo, Ariosto, and G. Sannazzaro. Many Cypriot scholars, like Ioannis Kigalas (c. 1622-1687), fled Cyprus during troubled times and contributed to scholarship abroad, particularly in Italy. Hasan Hilmi Efendi, a Turkish Cypriot poet, was recognized by the Ottoman sultan Mahmud II and called the "sultan of poems."

Modern Greek Cypriot literary figures include the poet and writer Costas Montis, poet Kyriakos Charalambides, poet Michalis Pasiardis, writer Nicos Nicolaides, Stylianos Atteshlis (Daskalos), Altheides, Loukis Akritas, and Demetris Th. Gotsis. Dimitris Lipertis, Vasilis Michaelides, and Pavlos Liasides are notable folk poets who wrote primarily in the Cypriot Greek dialect.

Leading Turkish Cypriot writers include Osman Türkay (twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature), Özker Yaşın, Neriman Cahit, Urkiye Mine Balman, Mehmet Yaşın, and Neşe Yaşın.

There is an increasing presence of émigré Cypriot writers in world literature, as well as writings by second and third-generation Cypriots born or raised abroad, often writing in English. These include authors such as Michael Paraskos and Stephanos Stephanides.

Cyprus has also featured in foreign literature, most famously in William Shakespeare's play Othello, which is largely set on the island. British writer Lawrence Durrell lived in Cyprus from 1952 to 1956 and wrote the memoir Bitter Lemons about his experiences, which won the Duff Cooper Prize in 1957.

9.4. Mass media

The media landscape in Cyprus is diverse, with numerous outlets operating in both the government-controlled areas and in Northern Cyprus. Freedom of the press and freedom of speech are generally respected in the Republic of Cyprus, as guaranteed by law and supported by an independent judiciary and a functioning democratic system. However, challenges can arise, sometimes related to the island's division or political sensitivities.

In the 2015 Freedom of the Press report by Freedom House, both the Republic of Cyprus and Northern Cyprus were rated "free." Reporters Without Borders ranked the Republic of Cyprus 24th out of 180 countries in its 2015 World Press Freedom Index.

- Television:** The state-owned Cyprus Broadcasting Corporation (CyBC, or RIK in Greek) operates multiple television and radio channels, providing news, cultural programming, and entertainment. Private television channels in the Republic of Cyprus include ANT1 Cyprus, Plus TV, Mega Channel (Cyprus), Sigma TV, and Alpha Cyprus. In Northern Cyprus, BRT (Bayrak Radio Television Corporation) is the public broadcaster, with several private channels also operating.

- Radio:** Numerous public and private radio stations cater to diverse tastes, offering music, news, and talk shows in Greek, Turkish, and English.

- Newspapers and Print Media:** A variety of daily and weekly newspapers are published in Greek, Turkish, and English. Prominent Greek-language dailies include Phileleftheros, Politis, and Simerini. English-language newspapers include the Cyprus Mail and The Cyprus Weekly. Turkish-language newspapers are published in the north.

- Online Media:** Online news portals and digital media platforms have become increasingly important sources of information and commentary.

Most local arts and cultural programming is produced by CyBC and BRT, including documentaries, review programs, and drama series.

9.5. Cinema

The Cypriot film industry is relatively small but has been growing, with support from government initiatives and international co-productions. The most internationally renowned Cypriot director is Michael Cacoyannis (1922-2011), known for films like Zorba the Greek (1964), Stella (1955), and Electra (1962).

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, George Filis produced and directed films such as Gregoris Afxentiou, Etsi Prodothike i Kypros (Thus Cyprus Was Betrayed), and The Mega Document.

Cypriot film production received a boost with the establishment of the Cinema Advisory Committee in 1994. The government allocates an annual budget for filmmaking. Cypriot co-productions are also eligible for funding from the Council of Europe's Eurimages fund. Films that have received Eurimages funding include I Sphagi tou Kokora (The Slaughter of the Rooster, 1996), To Tama (The Vow, 1999), and O Dromos gia tin Ithaki (The Road to Ithaca, 2000).

Greek director Vassilis Mazomenos filmed the drama Guilt in Cyprus in 2009. The Cyprus International Film Festival is an annual event.

Few foreign films have been made entirely in Cyprus, but parts of films like John Wayne's The Longest Day (1962) were shot on the island. Other foreign productions filmed in Cyprus include Incense for the Damned (1970), The Beloved (1970), and Ghost in the Noonday Sun (1973).

9.6. Cuisine

Cypriot cuisine is a rich blend of Mediterranean, Greek, Turkish, and Middle Eastern culinary traditions, reflecting the island's history and geographical position.

During the medieval period, under the French Lusignan monarchs, an elaborate courtly cuisine developed, fusing French, Byzantine, and Middle Eastern influences. Lusignan kings imported Syrian cooks, and it's suggested that Cyprus was a key route for Middle Eastern recipes (like blancmange) to enter Western Europe, known as vyands de Chypre (foods of Cyprus). Over one hundred such recipes have been identified in medieval European cookbooks. A popular stew, malmonia (chicken or fish), became known in English as mawmeny. Cauliflower, associated with Cyprus since the early Middle Ages and called "Cyprus cabbage" or "Cyprus colewart" in Western Europe, was also traded extensively from the island.

Though much Lusignan food culture was lost after the Ottoman conquest in 1571, some dishes survive, including forms of tahini, hummus, zalatina (pork brawn), skordalia (garlic dip), and pickled wild songbirds called ambelopoulia (now illegal but historically exported in large quantities).

Halloumi (Hellim in Turkish) cheese is arguably Cyprus's most famous culinary export. While some claim Byzantine origins, its name is likely Arabic. The earliest written record associating it with Cyprus is from 1554. Halloumi is commonly served sliced, grilled, or fried as an appetizer or part of a meze.

A typical Cypriot meal often starts with meze, a large selection of small dishes, including dips like tahini, tzatziki, and taramosalata, olives, various cheeses, and grilled items.

Seafood is popular, with dishes featuring squid, octopus, red mullet, and sea bass.

Common vegetable preparations include potatoes in olive oil and parsley, pickled cauliflower and beets, asparagus, and taro (kolokasi). Salads with cucumber and tomato are ubiquitous.