1. Background and Early Life

Nader Shah's early life was shaped by poverty, hardship, and the turbulent political landscape of late Safavid Iran, experiences that forged his character and ambition.

1.1. Birth and upbringing

Nader Shah was born in the fortress of Dastgerd in the northern valleys of Khorasan, a province in northeastern Safavid Iran. While his exact birth date is debated, sources suggest either November 1688 or August 6, 1698. His father, Emam Qoli, was a humble herdsman who may have also worked as a coatmaker, and his family lived a nomadic lifestyle. Nader was a long-awaited son in his family.

At the age of 13, Nader's father died, forcing him to support himself and his mother. He earned a meager living by gathering firewood and transporting it to the market. Years later, after his triumphant conquest of Delhi, he led his army to his birthplace and addressed his generals, reflecting on his impoverished youth. He advised them, "You now see to what height it has pleased the Almighty to exalt me; from hence, learn not to despise men of low estate." Despite this reflection, Nader's early experiences did not foster a particular compassion for the poor; his focus remained primarily on his own advancement.

Legend recounts that around 1704, when Nader was about 17, a band of marauding Uzbeks invaded Khorasan, where he lived with his mother. Many peasants were killed, and Nader and his mother were among those taken into slavery. His mother died in captivity. Another account suggests Nader convinced Turkmen to help him, promising future assistance. He returned to Khorasan in 1708.

1.2. Early activities

At the age of 15, Nader enlisted as a musketeer for a local governor. He steadily rose through the ranks, eventually becoming the governor's trusted right-hand man. This early military experience laid the groundwork for his exceptional career as a commander.

2. Rise to Power

Nader Shah's ascent to power occurred amidst the severe decline of the Safavid dynasty and widespread chaos caused by internal rebellions and foreign invasions, which he skillfully exploited to establish his dominance.

2.1. Fall of the Safavid dynasty and Afghan invasion

Nader grew up during the final years of the Safavid dynasty, which had ruled Iran since 1502. Once a powerful empire under figures like Abbas the Great, the Safavid state was in serious decline by the early 18th century, governed by the weak Shah Soltan Hoseyn. When Soltan Hoseyn attempted to suppress a rebellion by the Ghilzai Afghans in Kandahar, his appointed governor, Gurgin Khan, was killed. Under their leader Mahmud Hotaki, the rebellious Afghans advanced westward, defeating the Safavid forces at the Battle of Gulnabad in 1722 and subsequently besieging the capital, Isfahan. The city, starved into submission, saw Soltan Hoseyn abdicate, handing power to Mahmud.

Amidst this turmoil, Soltan Hoseyn's son, Tahmasp II, declared himself Shah but found little support, eventually fleeing to the Qajar tribe for backing. Meanwhile, Iran's traditional rivals, the Ottomans and the Russians, capitalized on the country's instability to seize and partition Iranian territory. In 1722, Russia, under Peter the Great and aided by Caucasian regents, launched the Russo-Iranian War, capturing swathes of Iranian land in the North Caucasus, South Caucasus, and northern mainland Iran, including Dagestan (with Derbent), Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran, and Astrabad. Simultaneously, the Ottomans took Iranian territories in Georgia, Iranian Azerbaijan, and Armenia. These newly acquired Russian and Turkish possessions were formalized and divided between them in the Treaty of Constantinople (1724). During this period of anarchy, Nader initially submitted to the local Afghan governor of Mashhad, Malek Mahmud, but later rebelled, building his own small army. He refused to pledge allegiance to Mahmud Hotaki when the latter began minting coins in his own name.

2.2. Support for Tahmasp II and Regency

Tahmasp II and the Qajar leader Fath Ali Khan (an ancestor of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar) sought Nader's assistance to expel the Ghilzai Afghans from Khorasan. Nader agreed, quickly becoming a figure of national importance. When Nader discovered Fath Ali Khan's treacherous correspondence with Malek Mahmud, he exposed him to Tahmasp, who then executed Fath Ali Khan and appointed Nader as the chief of his army. Nader adopted the title Tahmasp Qoli (Servant of Tahmasp). In late 1726, Nader successfully recaptured Mashhad.

Rather than marching directly on Isfahan, Nader first defeated the Abdali Afghans near Herat in May 1729, with many Abdali Afghans subsequently joining his army. The new Ghilzai Afghan Shah, Ashraf, moved against Nader but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Damghan in September 1729 and again at Murchakhort in November. Ashraf fled, and Nader finally entered Isfahan, restoring Tahmasp II to the throne in December. The citizens' celebrations were short-lived, however, as Nader plundered the city to pay his army. Tahmasp appointed Nader governor over several eastern provinces, including his native Khorasan, and Tahmasp's sister was married to Nader's son. Nader pursued and defeated Ashraf, who was ultimately murdered by his own followers. In 1738, Nader Shah besieged and destroyed the last Hotaki stronghold at Kandahar, building a new city nearby named "Naderabad."

Relations between Nader and Tahmasp II deteriorated as the Shah grew jealous of his general's military successes. While Nader was campaigning in the east, Tahmasp attempted to assert his authority by launching a disastrous campaign to recapture Yerevan. This resulted in the loss of all of Nader's recent gains to the Ottomans, and Tahmasp signed a treaty ceding Georgia and Armenia in exchange for Tabriz. Furious at this setback, Nader saw an opportunity to remove Tahmasp from power. He publicly denounced the treaty and rallied popular support for a war against the Ottomans. In Isfahan, Nader intoxicated Tahmasp and then presented him to the courtiers, questioning if a man in such a state was fit to rule. In 1732, Nader forced Tahmasp to abdicate in favor of his infant son, Abbas III, with Nader assuming the powerful position of regent.

3. Founding of the Afsharid Dynasty and Rule

Nader Shah's transition from regent to sovereign marked a pivotal moment in Iranian history, ending the Safavid era and establishing his own dynasty, accompanied by significant changes in governance and religious policy.

3.1. Coronation and establishment of the dynasty

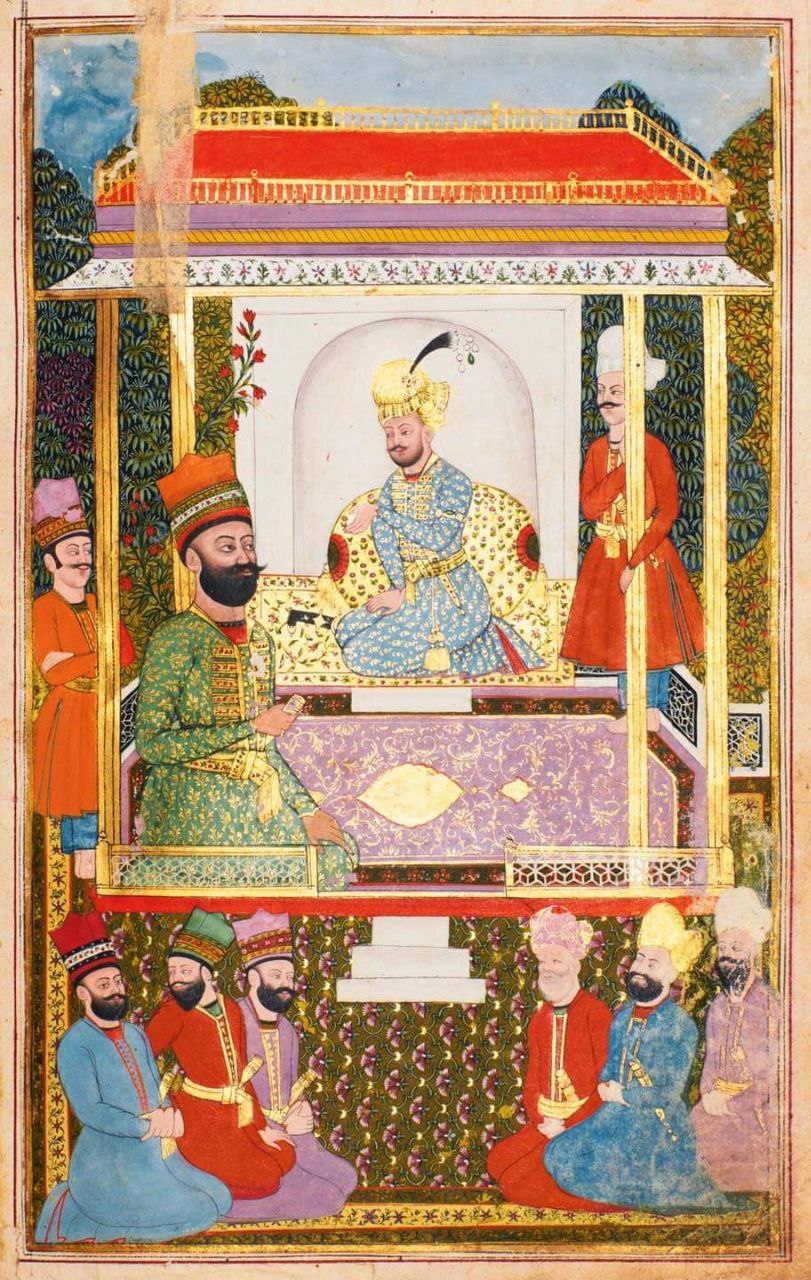

In January 1736, Nader convened a qoroltai (a grand meeting in the tradition of Genghis Khan and Timur) on the Mughan plains, a region specifically chosen for its size and abundant fodder. He suggested to his closest confidants, including Tahmasp Khan Jalayer and Hasan-Ali Beg Bestami, that he should be proclaimed the new king (shah) in place of the young Abbas III. While his intimates did not openly object, Hasan-Ali suggested that Nader should assemble all leading men of the state to receive their formal consent in a "signed and sealed document." Nader approved, and orders were dispatched to the military, clergy, and nobility across the nation to gather on the plains.

The summonses were sent out in November 1735, with attendees arriving from January 1736. During the qoroltai, everyone present agreed to Nader's proposal to become the new king. Many expressed enthusiastic support, while others, fearing Nader's wrath, silently acquiesced, unwilling to show support for the deposed Safavids. Nader was crowned Shah of Iran on March 8, 1736, a date chosen by his astrologers as particularly auspicious. The coronation took place in the presence of an "exceptionally large assembly" comprising military leaders, religious figures, nobility, and the Ottoman ambassador Ali Pasha.

As part of his ascension, Nader struck a deal with the notables and clergy: he would only assume the position of Shah if they agreed to certain conditions. These included refraining from cursing Omar and Uthman, avoiding self-flagellation during the Ashura festival, accepting Sunni practices as legitimate, and pledging obedience to Nader's children and relatives after his death, thereby establishing his own dynasty. These terms effectively signaled a realignment of Persia with Sunni Islam, and the notables accepted.

3.2. Religious policy

The Safavids had historically enforced Shia Islam as the state religion of Iran. While Nader may have been raised as a Shiite, he later replaced Shia law with a version more sympathetic and compatible with Sunni law, which he termed the "Ja'fari school." This move was partly to distance the state from radical Shia Islam, to appease his supporters, and to improve relations with other Sunni powers, particularly the Ottoman Empire. He believed that the Safavid emphasis on Shia Islam had intensified conflict with the Sunni Ottomans.

Nader's army was a diverse force, comprising a mix of Shia and Sunni Muslims, alongside a notable minority of Christians and Kurds, including his own Qizilbash, as well as Uzbeks, Afghans, Christian Georgians, and Armenians. He aimed for Iran to adopt a form of religion more acceptable to Sunni Muslims, proposing "Ja'fari" Islam, named in honor of the sixth Shia Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq. He banned Shia practices deemed offensive to Sunnis, such as the cursing of the first three caliphs of Islam.

Personally, Nader is said to have been indifferent towards religion. His French Jesuit personal physician reported that it was difficult to discern Nader's religious affiliation, with many close to him believing he had none. Nader hoped that "Ja'farism" would be recognized as a fifth school (madhhab) of Sunni Islam, allowing its adherents to undertake the hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, which was under Ottoman control. While the Ottomans refused to acknowledge Ja'farism as a fifth mazhab in subsequent peace negotiations, they did permit Iranian pilgrims to perform the hajj. Nader's interest in securing hajj rights for Iranians was partly motivated by the potential revenues from pilgrimage trade.

Another primary aim of his religious reforms was to further weaken the Safavids, as Shia Islam had been a major pillar of support for their dynasty. He ordered the strangulation of a Shia mullah who expressed support for the Safavids. Among his reforms was the introduction of the kolah-e Naderi, a distinctive hat with four peaks. These peaks symbolized either the first four caliphs of Islam or the four territories of Persia, India, Turkestan, and Khwarezm. Nader also diverted funds traditionally allocated to Shia mullahs, redirecting them to his army instead.

In 1741, Nader commissioned a translation of the Koran and the Gospels by eight Muslim scholars and three European and five Armenian priests. The project was overseen by Mīrzā Moḥammad Mahdī Khan Monšī, the court historiographer and author of the Tarikh-e-Jahangoshay-e-Naderi (History of Nader Shah's Wars). The completed translations were presented to Nader Shah in Qazvin in June 1741, though he was reportedly unimpressed.

4. Military Conquests

Nader Shah's military campaigns were extensive and strategically brilliant, enabling him to consolidate power, reclaim lost territories, and expand his empire across vast regions of Asia.

4.1. Consolidation of power and campaigns against Afghans

After his coronation, Nader focused on consolidating his power and eliminating remaining threats. He launched campaigns to unify Iran, suppressing internal rebellions that arose from various tribal groups and regional leaders. A key objective was to fully expel the Afghan forces that had destabilized Iran. Following his earlier victories against the Ghilzai and Abdali Afghans, he pursued them relentlessly, ultimately leading to the Siege of Kandahar in 1738, which destroyed the last Hotaki stronghold. His success in unifying Iran and driving out the Afghans solidified his control over the Persian realm.

4.2. Ottoman-Persian Wars

Nader Shah engaged in multiple military conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, Iran's traditional rival, aiming to reclaim territories lost during the Safavid decline. In the spring of 1730, Nader launched his first major offensive against the Ottomans, successfully regaining most of the territories they had seized. However, this campaign was interrupted by a rebellion of Abdali Afghans who besieged Mashhad, forcing Nader to suspend his western campaign to relieve his brother, Ebrahim. It took Nader fourteen months to suppress this uprising.

During Nader's absence, Tahmasp II's ill-fated campaign to recapture Yerevan resulted in the loss of Nader's recent gains to the Ottomans, and Tahmasp signed a treaty ceding Georgia and Armenia in exchange for Tabriz. Nader, infuriated by this setback, used it as a pretext to depose Tahmasp.

Resuming the 1730-1735 war, Nader planned to regain lost territories by capturing Ottoman Baghdad and using it as leverage. However, his army suffered a rare defeat at the hands of the Ottoman general Topal Osman Pasha near Baghdad in 1733, the only time Nader was ever routed in battle. Nader's troops, under Mohammad Khan Baloch, were defeated after hours of fighting. Facing widespread revolts in Iran, Nader quickly regrouped. He confronted Topal again with a larger force, defeating and killing him. He then besieged Baghdad and Ganja in the northern provinces, securing an alliance with Russia against the Ottomans. Nader achieved a significant victory over a superior Ottoman force at Baghavard, and by the summer of 1735, Iranian Armenia and Georgia were back under his control. In March 1735, he signed the Treaty of Ganja with the Russians, who agreed to withdraw all their troops from Iranian territory that had not been ceded back by the 1732 Treaty of Resht, thus reestablishing Iranian rule over the entire Caucasus and northern mainland Iran.

In 1743, Nader initiated another war against the Ottoman Empire. Despite commanding a massive army, this campaign saw less of his former military brilliance. The conflict concluded in 1746 with the signing of the Treaty of Kerden, in which the Ottomans agreed to allow Nader to occupy Najaf.

4.3. Invasion of India

After conquering Kandahar in 1738, Nader Shah turned his attention to the Mughal Empire of India. This once-powerful Muslim state in the east was in decline, plagued by disobedient nobles and expanding local opponents such as the Sikhs and Hindu Marathas. Its ruler, Muhammad Shah, was powerless to halt this disintegration. Nader, using the pretext of Afghan rebels taking refuge in India, crossed the border and invaded the militarily weak but immensely wealthy empire.

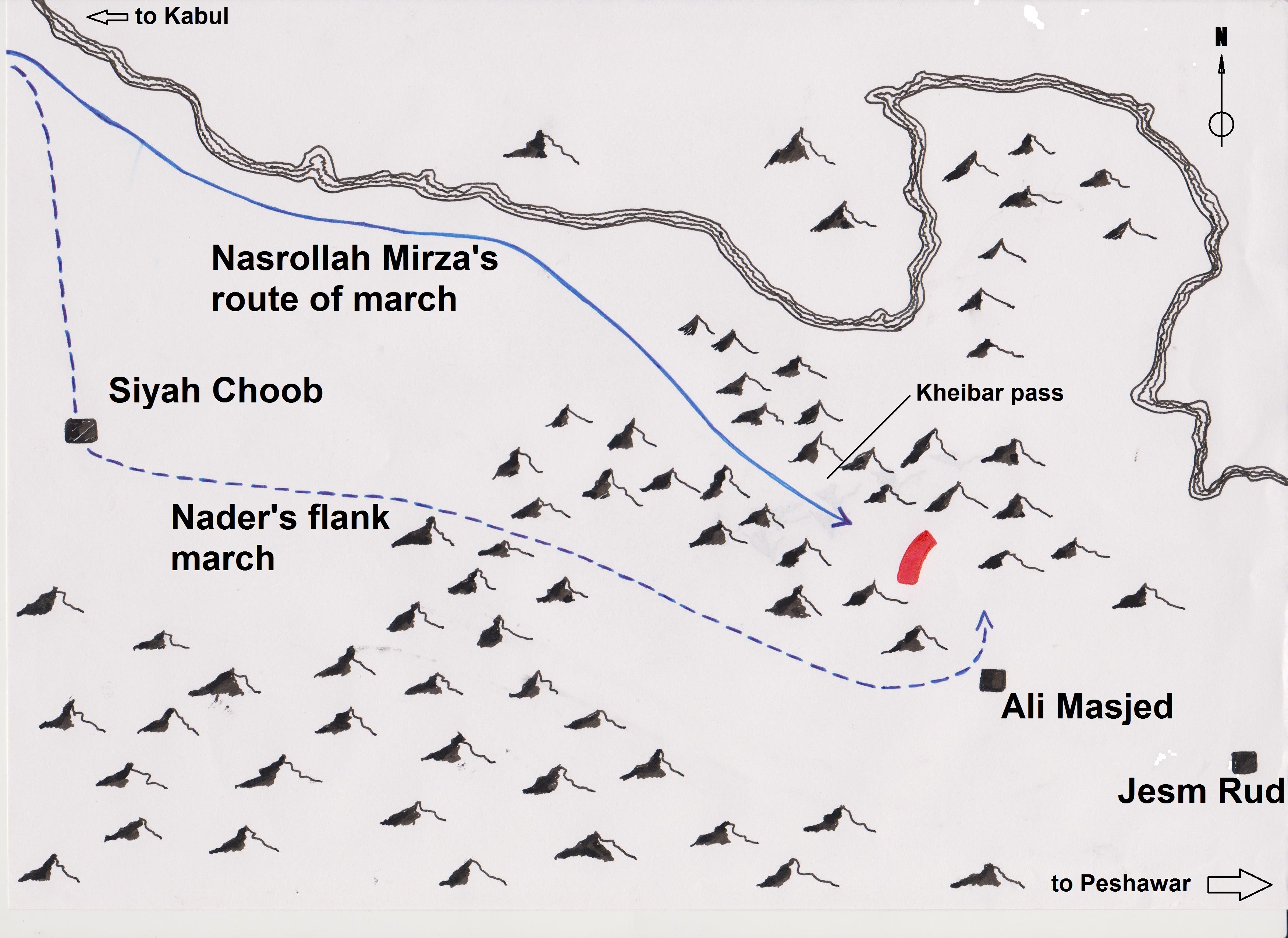

In a brilliant campaign against the governor of Peshawar, Nader led a small contingent of his forces through nearly impassable mountain passes, taking the enemy forces at the mouth of the Khyber Pass completely by surprise. He decisively defeated them despite being outnumbered two-to-one. This victory led to the capture of Ghazni, Kabul, Peshawar, Sindh, and Lahore. As he advanced into Mughal territories, he was loyally accompanied by his Georgian subject, Erekle II, the future king of eastern Georgia, who commanded a Georgian contingent within Nader's army. Following the defeat of Mughal forces, Nader continued deeper into India, crossing the Indus before the end of the year. News of the Iranian army's swift successes against the northern Mughal vassal states caused great alarm in Delhi, prompting Muhammad Shah to raise an army of some 300,000 men to confront Nader Shah.

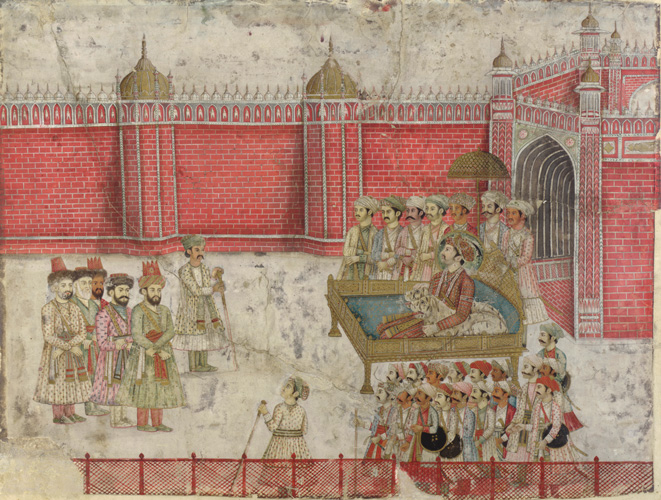

Despite being outnumbered by six to one, Nader Shah crushed the Mughal army in less than three hours at the Battle of Karnal on February 13, 1739. Following this spectacular victory, Nader captured Mohammad Shah and entered Delhi. A rumor then spread that Nader had been assassinated, leading some Indians to attack and kill Iranian troops; by midday, 900 Iranian soldiers had been killed. Enraged, Nader ordered his soldiers to sack the city. On March 22, 20,000 to 30,000 Indians were killed by Iranian troops, and as many as 10,000 women and children were taken as slaves, forcing Mohammad Shah to beg Nader for mercy.

Nader Shah agreed to withdraw, but Mohammad Shah paid a heavy price, surrendering the keys to his royal treasury and losing even the fabled Peacock Throne to the Iranian emperor. The Peacock Throne subsequently became a symbol of Iranian imperial might. It is estimated that Nader plundered treasures worth as much as 700.00 M INR. Among a trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also looted the Koh-i-Noor (meaning "Mountain of Light" in Persian) and Darya-ye Noor (meaning "Sea of Light") diamonds. The Iranian troops departed Delhi in early May 1739, but before leaving, Nader ceded back to Muhammad Shah all territories east of the Indus that he had overrun. The immense booty collected was loaded onto 700 elephants, 4,000 camels, and 12,000 horses.

Nader Shah's army left the area via the mountains in Northern Punjab. Learning of his route, the Sikhs gathered light cavalry bands and launched an attack to seize his plunder. The Sikhs fell upon Nader's army in the Chenab valley, capturing a large amount of the booty and freeing most of the slaves. The Persians, overloaded with the remaining plunder and overwhelmed by the terrible May heat, were unable to pursue the Sikhs. Traveling with an advance guard, Nader Shah stopped at Lahore, where he learned of his losses. He returned to his forces, accompanied by Governor Zakariya Khan. Upon learning about the Sikhs, he reportedly told Khan that these rebels would one day rule the land. Despite these losses, the remaining plunder from India was so vast that Nader was able to suspend taxation in Iran for three years following his return. Many historians believe Nader attacked the Mughal Empire to provide his country with a period of recovery after previous turmoil. His successful campaign and replenishment of funds allowed him to continue his wars against the Ottoman Empire and campaigns in the North Caucasus. Nader also secured one of the Mughal emperor's daughters, Jahan Afruz Banu Begum, as a bride for his youngest son.

4.4. Central Asian and Dagestan Campaigns

The Indian campaign marked the zenith of Nader's career. Afterward, his health declined significantly, and he became increasingly despotic. During Nader's absence, his son Reza Qoli Mirza had governed Iran. Reza had acted high-handedly and somewhat cruelly but maintained peace. Hearing rumors of his father's death, he had prepared to assume the crown, including ordering the murder of the former Shah Tahmasp and his family, including the nine-year-old Abbas III. Upon hearing this, Reza's wife, Tahmasp's sister, committed suicide. Nader was displeased with his son's actions and reprimanded him, but he took Reza on his expedition to conquer territory in Transoxiana.

In 1740, Nader conquered the Khanate of Khiva. After the Iranians forced the Uzbek Khanate of Bukhara to submit, Nader desired Reza to marry the khan's elder daughter, as she was a descendant of his hero Genghis Khan. However, Reza flatly refused, and Nader married the girl himself.

Regarding Central Asia, Nader considered Merv (present-day Bayramali, Turkmenistan) vital for his northeastern defenses. He also sought to establish the ruler of Bukhara as his vassal, emulating previous great conquerors of Mongol-Timurid descent. According to British scholar Peter Avery, Nader's attitude toward Bukhara was so irredentist that he "may even have thought that, if only the Ottoman power in the west could be contained, he might make Bukhara a base for conquests further afield in Central Asia." Nader dispatched numerous artisans to Merv in preparation for a potential conquest of distant Kashgaria. While such a campaign did not materialize, Nader frequently sent funds and engineers to Merv to restore its prosperity and rebuild its ill-fated dam, though Merv did not ultimately regain its former prosperity.

Nader then decided to punish Dagestan for the death of his brother Ebrahim Qoli in a campaign a few years earlier. In 1741, while Nader was traveling through the forests of Mazanderan en route to fight the Dagestanis, an assassin attempted to kill him, but Nader was only lightly wounded. He began to suspect his son was behind the attempt and confined him to Tehran. Nader's deteriorating health exacerbated his temper. Perhaps his illness contributed to Nader losing the initiative in his war against the Lezgin tribes of Dagestan. To his frustration, they resorted to guerrilla warfare, and the Iranians made little progress against them. Although Nader managed to take most of Dagestan during his campaign, the effective guerrilla tactics employed by the Lezgins, as well as the Avars and Laks, made the Iranian re-conquest of this North Caucasian region short-lived. Several years later, Nader was forced to withdraw.

During the same period, Nader accused his son of orchestrating the assassination attempt in Mazanderan. Reza Qoli vehemently protested his innocence, but Nader had him blinded as punishment, ordering his eyes to be brought to him on a platter. Once his orders were carried out, Nader instantly regretted his decision, crying out to his courtiers, "What is a father? What is a son?" Soon after, Nader began executing nobles who had witnessed his son's blinding.

In his final years, Nader became increasingly paranoid, ordering the assassination of large numbers of suspected enemies. For instance, following his orders, his soldiers executed 150 monks at Monastery of Saint Elijah after they refused to convert to Islam. With the wealth acquired from his conquests, Nader also began to establish an Iranian navy. He built ships in Bushehr using lumber from Mazandaran and purchased thirty ships in India. He successfully recaptured the island of Bahrain from the Arabs and, in 1743, conquered Oman and its capital, Muscat.

5. Domestic Policies and Administration

Nader Shah implemented various administrative and economic reforms aimed at strengthening the state and supporting his military endeavors, though these often came at a significant cost to the civilian population.

5.1. Economic and administrative reforms

Nader changed the Iranian coinage system, introducing silver coins called Naderi, which were equivalent in value to the Mughal rupee. He discontinued the traditional policy of paying soldiers based on land tenure, a system that had been common under the Safavids. Like the later Safavids, he engaged in tribal resettlement, notably transforming the Shahsevan, a nomadic group in Azerbaijan whose name means "shah lover," into a tribal confederacy tasked with defending Iran against the neighboring Ottomans and Russians. Furthermore, he increased the number of soldiers directly under his command, reducing the military control held by tribal and provincial leaders. While these reforms may have strengthened the country's central authority, they did little to alleviate Iran's suffering economy, which was heavily burdened by his continuous military campaigns. Despite the economic strain on the populace, Nader consistently paid his troops on time.

5.2. Military reforms

Nader Shah undertook significant military reforms aimed at creating a highly effective and loyal fighting force. He reorganized his army, implementing new strategies that emphasized speed, discipline, and the integration of diverse ethnic groups. He increased the size of the standing army under his direct command, thereby reducing the reliance on and power of tribal and provincial military contingents. His army was a formidable force, composed of various groups including his own Qizilbash, as well as Uzbeks, Afghans, Christian Georgians, and Armenians. Beyond land forces, Nader also initiated efforts to build an Iranian navy, constructing ships in Bushehr with timber from Mazandaran and purchasing additional vessels from India. These reforms were crucial to his widespread military successes, allowing him to launch and sustain campaigns across vast territories.

6. Personality and Ideology

Nader Shah's character was a complex blend of military genius, personal austerity, and increasing cruelty, which profoundly shaped his reign and legacy.

6.1. Military genius and leadership

Nader Shah is widely recognized for his extraordinary strategic brilliance and leadership qualities, earning him comparisons to some of history's greatest conquerors, such as Napoleon and Alexander the Great. He was described as "the last great Asiatic military conqueror." His military success was nearly unprecedented for Muslim Shahs of his era. He idolized previous Central Asian conquerors like Genghis Khan and Timur, emulating their military prowess.

Nader was undaunted in battle, often leading from the front lines and inspiring courage among his soldiers. He was known for his meticulous planning and foresight, neglecting no measure dictated by military strategy. His flank march at the Battle of Khyber Pass has been lauded as a "military masterpiece." He had a powerful, unusually loud voice, capable of issuing commands to his troops from a distance of about 100 yd. He was austere in his daily life, preferring plain garments and disdaining the lavish lifestyles of the Safavids. Unlike his predecessors, Soltan Hoseyn and Tahmasp II, he restrained himself from excessive indulgence in his harem and liquor, maintaining simple eating habits. He often carried fried peas in his pocket to satisfy hunger during demanding government affairs or campaigns.

Nader's strong character was evident in his refusal to boast of a proud genealogy, often speaking of his simple origins. He believed that a diamond's value lay in its splendor, not its origin. A story recounts that when he demanded the daughter of the defeated Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah for his son Nasrullah, and was told a royal lineage of seven generations was required, Nader retorted, "Tell him that Nasrullah is the son of Nader Shah, the son and grandson of the sword, and so on, not until the 7th, but until the 70th generation." He held great contempt for the weak Muhammad Shah, who was described by a contemporary chronicler as a "puppet ruler" always with his mistress and a glass in hand. Nader once asked a holy man if paradise included "war and victory over the enemy." When answered negatively, Nader replied, "How can there be any pleasure then?"

French orientalist Louis Bazin described Nader Shah as someone "born for the throne" despite his obscure background, endowed with "all the great qualities that make heroes." He noted Nader's strong, tall physique, gloomy expression, aquiline nose, and penetrating eyes with a sharp gaze. Bazin also highlighted Nader's "rude and loud" voice, which he could soften when personal interest required.

6.2. Cruelty and tyranny

As Nader Shah's health declined, his temper worsened, and he became increasingly cruel and paranoid, particularly driven by his desire to extort more tax money for his military campaigns. He began to imitate the cruelty of his hero, Timur, ruthlessly crushing new revolts and building towers from his victims' skulls.

His tyrannical tendencies were evident in several brutal acts. In 1740, he ordered the execution of his former liege, Tahmasp II, and Tahmasp's two young sons, including the nine-year-old Abbas III. In 1741, after an assassination attempt in Mazanderan, Nader suspected his eldest son, Reza Qoli Mirza, of being behind it. Despite Reza Qoli's angry protests of innocence, Nader had him blinded as punishment, ordering his eyes to be brought to him on a platter. Upon seeing his son's eyes, Nader instantly regretted his decision, crying out, "What is a father? What is a son?" Soon afterward, he began executing the nobles who had witnessed his son's blinding.

In his last years, Nader's paranoia intensified, leading him to order the assassination of large numbers of suspected enemies. For example, his soldiers executed 150 monks at the Monastery of Saint Elijah after they refused to convert to Islam. These extreme and horrific actions caused immense suffering among his subjects, ultimately leading to widespread fear and resentment. As French orientalist Louis Bazin noted, Nader was "adored, feared and cursed at the same time," and his "repulsive greed and unprecedented cruelties... ultimately led to his fall."

7. Assassination and Death

Nader Shah's reign of increasing tyranny and paranoia culminated in his assassination, a plot orchestrated by his own officers who feared for their lives.

In 1747, Nader set off for Khorasan to punish Kurdish rebels. Some of his officers and courtiers, fearing they were next to be executed, conspired against him. The conspirators included two of his relatives: Muhammad Quli Khan, the captain of the guards, and Salah Khan, the overseer of Nader's household.

Nader Shah was assassinated on June 20, 1747 (or June 19, 1747, in some accounts), at Quchan in Khorasan. He was surprised in his sleep by approximately fifteen conspirators and stabbed to death. Despite being caught off guard, Nader managed to kill two of his assassins before he died.

The most detailed account of Nader's assassination comes from Père Louis Bazin, Nader's physician at the time, who relied on the eyewitness testimony of Chuki, one of Nader's favorite concubines. According to Bazin's account, around fifteen conspirators prematurely arrived at the agreed meeting place, forcing their way into the royal tent. The noise woke Nader, who shouted, "Who goes there? Where is my sword? Bring me my weapons!" The assassins were initially terrified and tried to flee but were forced back into the tent by the two main conspirators. Nader Shah had not yet had time to dress when Muhammad Quli Khan struck him with a sword, felling him. Two or three others followed suit. The wounded monarch, covered in blood, weakly attempted to rise and pleaded, "Why do you want to kill me? Spare my life and all I have shall be yours!" While he was still pleading, Salah Khan rushed forward, severed his head with a sword, and dropped it into the hands of a waiting soldier. Thus perished "the wealthiest monarch on earth."

8. Legacy and Evaluation

Nader Shah's death plunged his vast empire into immediate chaos, leading to its rapid disintegration and a period of civil war, yet his military achievements and policies left a lasting, complex impact on the region.

8.1. Collapse of the empire and successors

Following Nader Shah's assassination, his vast empire quickly disintegrated, and Iran fell into a period of anarchy and civil war. He was succeeded by his nephew, Ali Qoli, who renamed himself Adel Shah ("righteous king") and was likely involved in the assassination plot. Adel Shah was deposed within a year. During the ensuing power struggles among Adel Shah, his brother Ibrahim Khan, and Nader's grandson Shah Rukh, almost all provincial governors declared independence, establishing their own states.

The Uzbek khanates of Bukhara and Khiva regained their independence, and Oman also broke away. The Ottoman Empire reclaimed lost territories in Western Armenia and Mesopotamia. In the far east, Ahmad Shah Durrani proclaimed independence, marking the foundation of modern Afghanistan. Iran finally lost Bahrain to the House of Khalifa during the Bani Utbah invasion of Bahrain in 1783.

In the Caucasus, Erekle II and Teimuraz II, whom Nader had appointed kings of Kakheti and Kartli respectively in 1744 for their loyal service, capitalized on the instability and declared de facto independence. Erekle II later unified the two as the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, becoming the first Georgian ruler in three centuries to preside over a politically unified eastern Georgia. He maintained its autonomy until the advent of the Iranian Qajar dynasty. The remaining Iranian territories in the Caucasus, including modern-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Dagestan, fragmented into various khanates, whose rulers maintained varying degrees of autonomy but remained nominal vassals to the Iranian king until the rise of the Zand dynasty and Qajars.

Ultimately, Karim Khan founded the Zand dynasty and became the ruler of Iran by 1760. Nader's grandson, Shahrokh Shah, was the last of his dynasty to rule, ultimately being deposed in 1796 by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, who crowned himself shah the same year, establishing the Qajar dynasty.

8.2. Historical impact and evaluation

Nader Shah's military achievements were truly remarkable, making him one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian history. His victories briefly established him as West Asia's most powerful sovereign, ruling what was arguably the most powerful empire in the world. He is often described as "the last great Asiatic military conqueror." His campaigns, particularly the invasion of India, significantly altered the political landscape of the Middle East and Central Asia. The Indian campaign, for instance, alerted the East India Company to the extreme weakness of the Mughal Empire, paving the way for eventual British expansion in India. Some historians suggest that without Nader's intervention, British rule in India "would have come later and in a different form, perhaps never at all - with important global effects."

However, Nader's legacy is complex and marked by contrasting historical perspectives. While his military genius is universally acknowledged, his reign was also characterized by immense cruelty and economic devastation. His continuous warfare, though successful in expanding the empire, ruined the Iranian economy, leading to widespread suffering and popular discontent. His increasing paranoia and brutal purges in his later years alienated his subjects and ultimately led to his assassination.

Despite the short-lived nature of his vast empire, Nader Shah's influence on the subsequent era was profound. The Durrani dynasty in Afghanistan and the later Qajar dynasty in Iran both emerged from the power vacuum and military structures he created. Figures like Joseph Stalin and Napoleon Bonaparte are said to have admired Nader Shah, with Napoleon reportedly considering himself the "new Nader." A Punjabi contemporary poet described Nader's rule as a time "when all of India trembled with horror," while a Kashmiri historian, Lateef, lauded him as "the horror of Asia, the pride and savior of his country, the restorer of her freedom and conqueror of India, who, having a simple origin, rose to such greatness that monarchs rarely have from birth."

8.3. Cultural impact

Nader Shah's influence extended to cultural and architectural developments, particularly in Mashhad, which served as his de facto capital. Despite his nomadic lifestyle and preference for military camps over fixed palaces, he undertook significant construction projects in Mashhad. He ordered the renovation of the 8th Imam Ali al-Ridha shrine, adding minarets and improving the surrounding bazaar. The modern city of Mashhad, now Iran's second-largest city, effectively began its substantial development during Nader Shah's period.

Furthermore, Nader initiated large-scale civil engineering projects, including the construction of dams (bandarb) across rivers and wetlands in Khorasan and Sistan, as well as other traditional infrastructure like qanats. Many of these projects continue to impact the region today. His conscious avoidance of the color green, associated with Shia Islam and the Safavid dynasty, in his flags and symbols also reflects his attempt to reshape the cultural and religious identity of the state away from the Safavid legacy. His reign, though brief and tumultuous, profoundly reshaped the historical narratives and political structures of Iran and its neighboring regions.