1. Early Life and Background

Karl Ernst Haushofer was born in Munich, the capital of the Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire, on 27 August 1869. His early life was shaped by a family with a strong artistic and academic lineage, leading him towards a military career that would eventually transition into geographical research.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Haushofer completed his secondary education, graduating from the Humanistisches Gymnasium in Munich in 1887. Following graduation, he began his military career by enlisting as a one-year volunteer in the 1st Field Artillery Regiment "Prinzregent LuitpoldGerman" of the Bavarian Army. In 1888, he became an officer candidate within the same regiment. He underwent extensive military training, completing courses at the Bavarian War Academy (Kriegsschule), the Artillery Academy (Artillerieschule), and the Bavarian War Academy, which served as a gateway for senior officers.

1.2. Military Career Before WWI

After completing his academy training, Haushofer joined the General Staff in 1899, serving for two years. In 1901, he was promoted to Captain and spent three years commanding an artillery company. By 1903, he accepted a teaching position at the Bavarian War Academy, where he taught military history. In 1904, he was transferred to the Central Office of the General Staff. However, a later transfer to the staff of the Bavarian 3rd Division in Landau in 1907 was perceived by Haushofer as a punitive measure, leading him to abandon aspirations for further military advancement and instead focus on a career in geographical research.

In November 1908, Haushofer was dispatched to Tokyo, Japan, as a military attaché to study the Imperial Japanese Army and to serve as a military advisor for artillery instruction. He traveled with his wife, Martha Haushofer, via India and Southeast Asia, arriving in February 1909. During his posting, he was received by Emperor Meiji and developed acquaintances with many influential figures in Japanese politics and military circles. In the autumn of 1909, he and his wife embarked on a month-long journey to Korea and Manchuria, coinciding with railway construction projects in the region. Their return to Germany in June 1910, via Russia, came swiftly, but shortly thereafter, Haushofer suffered from a severe lung disease, necessitating a three-year leave from the army. His extensive travels throughout Asia during this period, particularly his time in Japan, profoundly influenced his later academic pursuits and the development of his geopolitical theories.

During World War I, Haushofer commanded a brigade on the Western Front. His experiences in the war, particularly the entry of the United States into the conflict, fueled bitter hatreds. He described America as a "deceitful, ravenous, hypocritical, shameless beast of prey," stating, "Americans are truly the only people on this world that I regard with a deep, instinctive hatred." Simultaneously, he developed a virulent strain of anti-Semitism, writing to his wife, Martha, of "Jewish treason against Volk, race and country." He repeated false slanders, alleging that Jews declined to fight for their country and were guilty of war profiteering. He concluded that the solution to Germany's ills required a powerful, charismatic leader, expressing his readiness for a "Caesar" and his willingness to serve as an instrument for such a figure.

2. Academic Activities and Geopolitical Theories

Upon retiring from the military as a Generalmajor (major general) in 1919, Karl Haushofer dedicated himself to academia, aiming to restore and regenerate Germany after its defeat in World War I. He firmly believed that Germany's lack of geographical knowledge and geopolitical awareness was a significant factor in its disadvantageous alignment of allies and enemies during the war.

2.1. Doctoral Studies and Early Academic Career

During his convalescence from 1911 to 1913, Haushofer pursued his Doctorate of Philosophy at Munich University. His doctoral thesis, titled Dai Nihon, Betrachtungen über Groß-Japans Wehrkraft, Weltstellung und Zukunft ("Reflections on Greater Japan's Military Strength, World Position and Future"), established him as a leading German expert on the Far East.

Following World War I, in 1919, Haushofer successfully defended his second dissertation, earning his Habilitation (a post-doctoral qualification) and becoming a Privatdozent (lecturer) in political geography at the University of Munich. In 1921, he was appointed professor of geography. He played a pivotal role in promoting geopolitical thought by founding the Institute of Geopolitics in Munich in 1922. By 1924, as a recognized leader of the German geopolitik school of thought, he established the monthly journal Zeitschrift für Geopolitik (ZfG), which he co-edited until its suspension near the end of World War II. Despite being made a full professor in 1933, he declined a formal position and salary to avoid affecting his military pension.

2.2. Development of Geopolitik

Haushofer's "Geopolitik" was a new discipline that combined fields such as geography, history, economics, demography, political science, and anthropology. While he struggled to plainly describe this "new science," its core principle viewed the state as an organism, whose character was shaped by its unique geography and history. Within this framework, he coined the term Lebensraum ("room to live") to describe the territory a healthy and expanding state needed to sustain its population. This concept was later adopted by Hitler and the Nazi Party in its most aggressive and militaristic interpretation, justifying crimes against peace and genocide.

Haushofer's geopolitical theories drew from a wide range of thinkers, including Oswald Spengler, Alexander Humboldt, Carl Ritter, Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellén, and Halford J. Mackinder. From these influences, his theories contributed five key ideas to German foreign policy during the interwar period:

- The organic state theory, viewing the state as a living entity that grows and adapts.

- Lebensraum, justifying territorial expansion as a biological necessity for national growth.

- Autarky, advocating economic self-sufficiency to reduce external dependencies.

- Pan-regionalism (Panideen), envisioning the world divided into large, self-sufficient spheres of influence, often modeled on the British Empire or the American Monroe Doctrine.

- The land power versus sea power dichotomy, emphasizing the strategic control of land-based empires.

His approach transformed descriptive political geography into a normative doctrine for national policy. While some of his ideas stemmed from earlier American and British geostrategy, German geopolitik adopted an essentialist outlook, oversimplifying complex issues and presenting itself as a panacea for the nation's post-World War I insecurity.

Haushofer leveraged his position at the University of Munich to disseminate his geopolitical ideas through magazine articles and books. His concept of Lebensraum gained wider popularity with the publication of Volk ohne Raum by Hans Grimm in 1926. He urged his students to "think in terms of continents" and emphasized "motion in international politics". While Hitler's speeches captivated the masses, Haushofer's works served to draw intellectuals into the National Socialist orbit.

Haushofer's geopolitik was essentially a consolidation of older ideas given a "scientific gloss." Lebensraum was a revised form of colonial imperialism; autarky was a new expression of tariff protectionism; and strategic control of key geographical territories mirrored earlier designs on choke points like the Suez Canal and Panama Canal, but with a focus on controlling landmasses. Pan-regions, influenced by the British Empire and the American Monroe Doctrine, envisioned a world divided into spheres of influence, promoting national and continental self-sufficiency. His view on frontiers was that they were fluid, determined by the will or needs of ethnic and racial groups, rather than fixed political borders or natural placements. The key reorientation in his work was a focus on land-based empire over naval imperialism.

Drawing upon the theories of American naval expert Alfred Thayer Mahan and British geographer Halford J. Mackinder (especially the Heartland Theory), German geopolitik incorporated older German ideas, notably from Friedrich Ratzel and his student Rudolf Kjellén. These included an anthropomorphized or organic conception of the state and the need for self-sufficiency through top-down societal organization. Karl Ritter was credited with first developing the organic state concept, later elaborated by Ratzel and adopted by Haushofer, who justified Lebensraum-even at the expense of other nations-as a biological necessity for state growth.

Ratzel's writings coincided with the growth of German industrialism after the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent search for markets that led to competition with Britain. Influenced by Mahan, Ratzel aspired for German naval reach, believing sea power to be self-sustaining. Haushofer, familiar with Ratzel through his father, integrated Ratzel's ideas on the division between sea and land powers into his theories, asserting that only a country possessing both could overcome this conflict. The Munich school, under Haushofer, specifically studied geography as it related to war and designs for empire, transforming previous geopolitical behavioral rules into dynamic normative doctrines for action on Lebensraum and world power.

In 1935, Haushofer defined geopolitik as "the duty to safeguard the right to the soil, to the land in the widest sense, not only the land within the frontiers of the Reich, but the right to the more extensive Volk and cultural lands." He viewed culture as the most conducive element for dynamic spatial expansion, guiding optimal areas for expansion and making it safe, unlike projected military or commercial power. He even considered urbanization a symptom of national decline, indicating decreasing soil mastery, birthrate, and effectiveness of centralized rule.

For Haushofer, a state's existence hinged on living space. He argued that Germany, with its high population density, compared to the much lower densities of old colonial powers, had a virtual mandate for expansion into resource-rich areas. Space was also seen as military protection against assaults from hostile neighbors. A buffer zone of territories or insignificant states along borders would serve to protect Germany. He asserted that the existence of small states signified political regression and disorder in the international system, suggesting they should be integrated into a vital German order. He cited Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, Denmark, Switzerland, Greece, and the "mutilated alliance" of Austria-Hungary as examples supporting his view that these states were too small for practical autonomy and would benefit from German protection and organization.

Haushofer's concept of autarky was rooted in a quasi-Malthusian idea that the earth would become saturated with people, unable to provide sufficient food, with no significant increases in productivity possible. His Munich school eventually expanded their conception of Lebensraum and autarky beyond the 1914 borders and "a place in the sun" to a New European Order, then a New Afro-European Order, and ultimately a Eurasian Order. This concept, known as a pan-region, drew inspiration from the American Monroe Doctrine and the idea of national and continental self-sufficiency. It was a forward-looking re-fashioning of the drive for colonies, not viewed as an economic necessity but more as a matter of prestige, putting pressure on older colonial powers. The fundamental motivating force was cultural and spiritual. Haushofer was a proponent of "Eurasianism", advocating a policy of German-Russian hegemony and alliance to offset the potentially dominating influence of an Anglo-American power structure in Europe. Beyond economic considerations, pan-regions were also a strategic concept, acknowledging Mackinder's Heartland Theory. Haushofer believed that if Germany controlled Eastern Europe and subsequently Russian territory, it could control a strategic area from which hostile seapower could be denied. An alliance with Italy and Japan would further augment German strategic control of Eurasia, with those states acting as naval arms protecting Germany's insular position.

3. Relationship with the Nazi Regime

Haushofer's relationship with the Nazi regime was complex and contentious. While he was never a member of the Nazi Party, his intellectual contributions provided a significant, albeit often distorted, foundation for Nazi ideology, particularly regarding expansionist policies.

3.1. Influence on Hitler and Nazi Ideology

Haushofer's direct contact with Rudolf Hess began in 1919, when Hess became his student. Through Hess, Haushofer met Adolf Hitler in 1921. After the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Hitler was imprisoned in Landsberg Prison, and Hess voluntarily joined him. Haushofer frequently visited them in prison, becoming a political and philosophical mentor. According to scholar Holger Herwig, Haushofer made the 62 mile (100 km) round trip from Munich to Landsberg every Wednesday between June and December 1924, offering "hours of intense personal mentoring" to Hess and Hitler, whom he called "young eagles." Joachim Fest, a prominent Hitler biographer, stated that Hess's most significant personal contribution to the creation of National Socialism was bringing Haushofer and Hitler together. Albrecht Haushofer, Karl's son, believed his father's credibility as a general and professor lent immense weight to his visits, significantly impacting the nascent Nazi movement.

Hitler reportedly "soaked up what Haushofer offered," becoming particularly interested in the concept of Lebensraum. Hitler adapted this theory to assert that a German nation without sufficient living space must pursue military expansion. However, Haushofer himself expressed concern that Hitler did not truly grasp the complex principles of geopolitics, seeing him as a "half-educated man" who lacked the correct perspective for understanding these concepts. Haushofer reportedly attempted to lecture Hitler on the fundamentals of geopolitics, but Hitler, suspicious of formally educated individuals, rejected these lessons. Haushofer later claimed that Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Foreign Minister, was the primary distorter of geopolitik in Hitler's mind.

From 1925 to 1931 and again from 1933 to 1939, Haushofer broadcast monthly radio lectures on the international political situation. These "Weltpolitischer MonatsberichtGerman" (World Political Monthly Reports) made him a household name in Germany. He was a founding member of the Deutsche Akademie, serving as its president from 1934 to 1937. He was a prolific writer, publishing hundreds of articles, reviews, commentaries, obituaries, and books, many focusing on Asian topics, and he ensured that many Nazi Party and military leaders received copies of his works. Under Hitler's regime, Haushofer became both wealthy and immensely influential. Through his teaching and writing, he provided Hitler and the Nazis with an intellectual legitimacy, giving them a political and philosophical vocabulary to justify their goals of war and terror. He was also instrumental in forging links between Japan and the Axis powers, aligning with the theories presented in his book Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean.

3.2. Position and Conflicts Under Nazism

Despite his significant influence, Haushofer was never a member of the Nazi Party and, at times, voiced disagreements with its policies. He came under suspicion due to his contacts with left-wing socialist figures within the Nazi movement, such as Gregor Strasser, and his consistent advocacy for a German-Russian alliance. This aligned with the National Bolshevism philosophy of a German-Russian revolutionary alliance, championed by figures like Ernst Niekisch, Julius Evola, Ernst Jünger, and Friedrich Hielscher. Although Haushofer outwardly professed loyalty to the Führer and occasionally made anti-Semitic remarks, his core emphasis was on space over race, believing in environmental rather than racial determinism. Crucially, he declined to actively associate himself with state-sponsored anti-Semitism, largely because his wife, Martha, was half-Jewish.

The complex nature of his position became even more strained after his patron, Rudolf Hess, flew to Scotland in May 1941 in a failed attempt to negotiate peace with the United Kingdom. Hess was purged from the Nazi Party, and the Haushofer family, with its close ties to Hess and Jewish background, came under renewed suspicion. Haushofer claimed that much of what he wrote after 1933 was distorted under duress, as he had to protect his wife, who, through Hess's influence, was awarded "honorary German" status under the Nuremberg Laws. His son and grandson were even imprisoned for two and a half months during this period.

In 1939, Haushofer also held a position within the "Volksdeutsche MittelstelleGerman" (Ethnic German Liaison Office), an SS-operated agency responsible for coordinating with ethnic Germans outside the Reich. This involvement illustrates the degree to which he navigated and, to some extent, cooperated with Nazi structures despite his personal moral conflicts.

After World War II, Haushofer denied that he had taught Hitler directly or that the Nazis perverted Hess's study of geopolitik. He claimed that Hitler and the Nazis only seized upon "half-developed ideas and catchwords" and that the Nazi party lacked any official organ truly receptive to geopolitik, leading to selective adoption and poor interpretation of his theories. He insisted that only Hess and Konstantin von Neurath, the German Minister of Foreign Affairs, possessed a proper understanding of geopolitik.

However, Father Edmund A. Walsh, a professor of geopolitics and dean at Georgetown University, who interviewed Haushofer after the Allied victory, disagreed with Haushofer's assessment. Walsh argued that Hitler's speeches, which declared small states had no right to exist, and the Nazi use of Haushofer's maps, language, and arguments, were sufficient to implicate Haushofer's geopolitical theories, even if somewhat distorted. Walsh found that new geopolitical elements, such as Lebensraum, space for depth of defense, appeals for natural frontiers, balancing land and sea power, and geographic analysis of military strategy, appeared in Mein Kampf after Hitler's imprisonment, indicating Haushofer's influence. Hans Frank, the governor general of wartime Poland, quoted Hitler as saying, "Landsberg was my university education at state expense."

Various unproven allegations have been presented about Haushofer's more obscure involvement with political extremism, including claims that he was a former student of the Greek-Russian mystic George Gurdjieff, that he created a Vril Society, or was a secret member of the Thule Society. Some theorists also claimed that Haushofer co-wrote or helped to write Mein Kampf, or even that he was Hess's father or that the two men were lovers. Scholar Holger Herwig dismisses these as "mythmaking" and "rumors." Haushofer himself denied assisting Hitler in writing Mein Kampf, stating he only learned of it once it was in print and never read it. Haushofer's influence on Nazi ideology was dramatized in the 1943 short documentary propaganda film, Plan for Destruction, which was nominated for an Academy Award.

4. Personal Life and Family

Karl Ernst Haushofer's private life was intertwined with the turbulent political events of his time, particularly through his marriage and family.

4.1. Family Background and Marriage

Haushofer came from a family with a strong academic and artistic heritage. His grandfather, Max Haushofer, was a painter and a professor at the Prague Art Academy. His father, Max Haushofer Jr., was a notable economist, politician, and author.

In 1896, Karl Haushofer married Martha Mayer-Doss (1877-1946). Martha's father was Jewish, and her family had converted from Judaism to Catholicism in the generation prior to her marriage. Together, Karl and Martha had two sons: Albrecht Haushofer and Heinz Haushofer (1906-1988). Martha's cousin was the jurist Max Ernst Mayer.

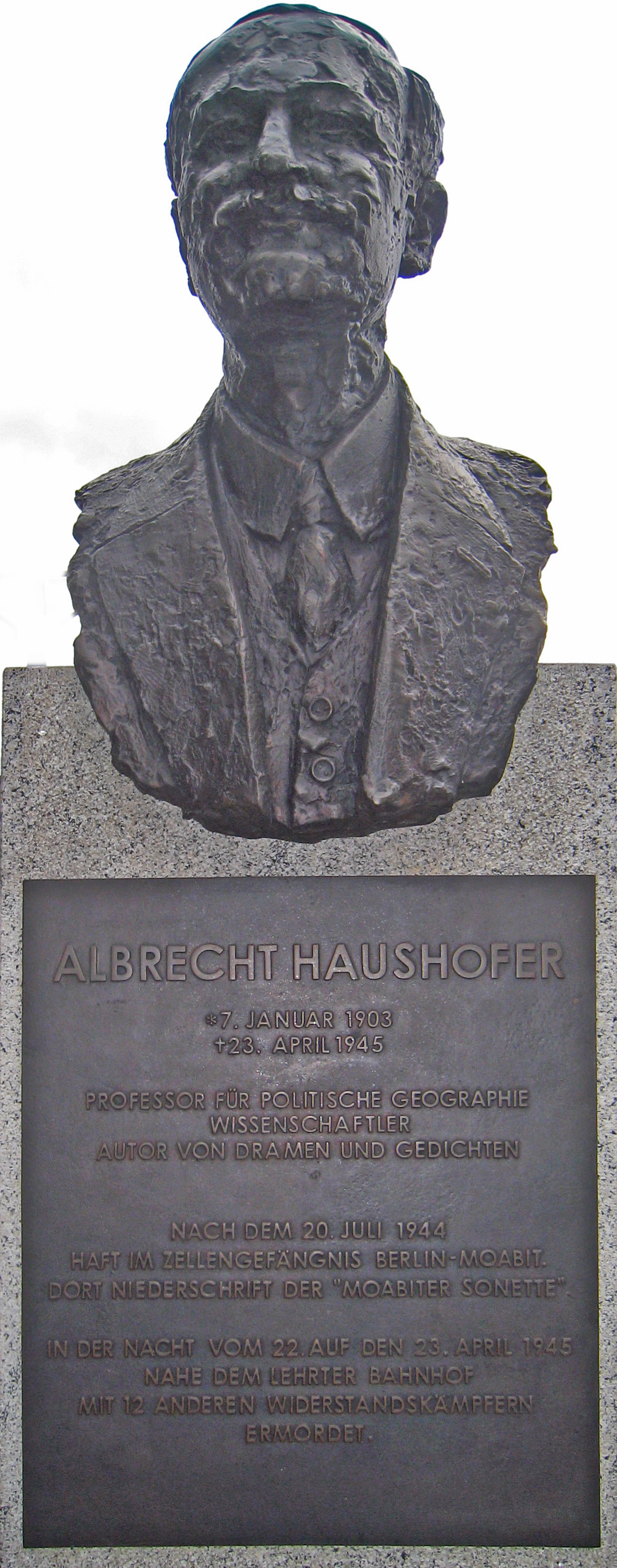

4.2. Son Albrecht and the July 20 Plot

The Nazi regime's discriminatory policies directly impacted Haushofer's family due to his wife's Jewish ancestry, leading to their categorization as Mischlinge under the Nuremberg Laws. Despite this, his elder son, Albrecht Haushofer, who was also a geographer and diplomat, exceptionally became a university professor through the influence of Rudolf Hess.

However, the family's precarious position worsened significantly when Albrecht Haushofer became involved in the 20 July plot to assassinate Hitler in 1944. Karl Haushofer himself was arrested on 28 July 1944 and imprisoned for a month at Dachau concentration camp before being released. Albrecht went into hiding but was ultimately arrested on 7 December 1944 and confined to Moabit Prison in Berlin. Karl wrote a personal letter to Hitler pleading for his son's mercy, though he never sent it. During the night of 22-23 April 1945, just days before the end of the war, Albrecht and other prisoners, including Klaus Bonhoeffer, were led out of the prison by an SS death squad and executed on the orders of Josef Goebbels. When his brother Heinz found his body, Albrecht was still clutching a sheaf of papers on which he had written dozens of poems in his final days, attempting to reconcile his life, his father's work, and the war. These eighty poems were later published as The Moabit Sonnets. In the thirty-eighth sonnet, titled "The Father," Albrecht tragically indicted his father for his role in inadvertently aiding the rise of Nazism:

"My father broke away the seal.

He did not see the rising breath of evil.

He let the demon soar into the world."

Karl Haushofer was profoundly devastated by Albrecht's death. Yet, even after the Nazis had murdered his beloved son and left Germany in ruins, he continued to attribute the destruction of his cherished Munich to "New York's finance Jews."

5. Later Life and Death

After Germany's defeat in World War II, Karl Haushofer faced scrutiny for his extensive influence on Nazi ideology and policy.

5.1. Post-War Interrogation

Haushofer was repeatedly arrested by American forces following the war. Beginning on 24 September 1945, he underwent informal interrogations conducted by Father Edmund A. Walsh on behalf of Robert H. Jackson, the chief prosecutor for the Nuremberg Trials. The purpose of these interrogations was to determine whether Haushofer should also face trial as a major war criminal.

Father Walsh ultimately concluded and reported to Jackson that Haushofer was both legally and morally complicit in Nazi war crimes. Walsh asserted that Haushofer and his associates were "basically as guilty as the better-known war criminals," citing "the role of geopolitics in corrupting education into a preparation for war." In his later memoir of the Nuremberg Trials, Walsh further alleged that "The tragedy of Karl Haushofer" was his participation in the "nationalizing" of academic scholarship and of turning Geopolitik into a weapon, thereby supplying "an allegedly scientific basis and justification for international brigandage." Despite Walsh's strong assessment of his guilt, Haushofer was not formally prosecuted at Nuremberg due to his advanced age, poor health, and the perceived difficulty in proving his direct involvement in specific war crimes.

5.2. Suicide

On the night of 10-11 March 1946, Karl Haushofer and his wife, Martha, committed suicide together in a secluded hollow on their Hartschimmelhof estate at Pähl/Ammersee, located in the American Zone of Occupied Germany. Both ingested arsenic, and Martha then hanged herself from a tree branch. Haushofer left a detailed map to help his son, Heinz, locate their bodies. In his suicide note, he explicitly stated his desire for oblivion: "no form of state or church funeral, no obituary, epitaph, or identification of my grave... I want to be forgotten and forgotten."

Father Walsh, who visited their graves, noted in his diary the profound tragedy of their isolated death, reflecting on the grim end of "the last of the geopoliticians."

6. Legacy and Reception

Karl Haushofer's legacy is marked by the enduring influence of his geopolitical ideas and the severe criticism linking them to the atrocities of Nazi Germany. As a central figure in the intellectual origins of Nazi ideology, Haushofer is often included in lists of Nazi ideologues.

6.1. Influence

Haushofer was a prominent advocate for a German-Russian alliance and Eurasianism, believing in a continental land power bloc that could offset the perceived dominance of Anglo-American naval power. His views significantly influenced the Nazi left-wing, particularly figures like Gregor Strasser, and resonated with elements of National Bolshevism and some leaders within the Communist Party of Germany. However, his relationship with Hitler became estranged after the start of the German-Soviet War, a conflict he had opposed from a geopolitical standpoint. In recent years, Haushofer's ideas have been cited as an influence on modern Neo-Eurasianism, notably associated with thinkers like Alexandr Dugin, particularly in the context of geopolitical events such as the Ukraine War.

His experience as a military attaché in Japan was pivotal, shaping his development as a geopolitician. Haushofer was largely pro-Japanese, viewing Japan as an Asian parallel to Germany in Europe. He authored numerous works on Japan's military strength, its aspirations for hegemony in Asia, and its economic development, including a book on Emperor Meiji. He advocated for a German-Soviet-Japanese alliance to establish a new world order based on continental blocs. Consequently, he opposed Japan's Northward Advance policies (towards Manchuria and beyond) and the Second Sino-Japanese War, instead advocating for a Southward Advance for Japan. He also engaged in covert activities with the Japanese military to promote this strategy, but these efforts ultimately failed. During his time in Japan, he learned Japanese, Korean, and Chinese. He traveled extensively across Asia, gaining deep knowledge of Hinduism and Buddhism scriptures, and showed a particular interest in the Aryan populations of North India and Iran, earning him a reputation as an authority on Asian mysticism.

Haushofer proposed that the world should be divided into several major blocs or "pan-regions," with countries like America, the Soviet Union, Japan, and Germany holding dominant positions within their respective regions to maintain global order. This approach, while appearing to advocate for a Balance of Power theory on a global scale, fundamentally placed Germany as the leader coordinating these blocs.

6.2. Criticism and Controversies

Haushofer's legacy is heavily criticized due to the direct link between his geopolitical theories and Nazi Germany's aggressive expansionist policies, including the atrocities of the Holocaust. He is often described as "Hitler's evil genius," a term notably used by Donald Hawley Norton, for providing an intellectual veneer to the Nazi regime's destructive ambitions.

Despite Haushofer's post-war claims that his theories were distorted by the Nazis and that he did not fully understand Hitler, his critics argue otherwise. Father Edmund A. Walsh, who interrogated him, disagreed with Haushofer's claims of intellectual distance, citing Hitler's public speeches that denied the right of small states to exist and the extensive use of Haushofer's maps, language, and arguments by the Nazis. Walsh argued that even if distorted, Haushofer's geopolitik provided ample justification for Nazi aggression.

The most damning criticism came from his own son, Albrecht Haushofer, whose final poems written before his execution condemned his father for unleashing the "demon" of Nazism. In "The Father," Albrecht wrote: "My father broke away the seal. He did not see the rising breath of evil. He let the demon soar into the world." This personal indictment highlights the profound moral and ethical implications of Karl Haushofer's intellectual legacy. Even after his son's murder by the Nazis and Germany's devastation, Karl Haushofer continued to blame "New York's finance Jews" for the destruction of Munich, revealing a persistent adherence to anti-Semitic conspiracy theories despite his personal circumstances.

Historians continue to debate the exact extent of Haushofer's direct influence on Hitler, with some, like Ian Kershaw, suggesting it was greater than Haushofer admitted, while others, like Joachim Fest, argue that Hitler's version of the ideas was distinctly his own. Nevertheless, the consensus remains that Haushofer's concepts provided a potent ideological framework that the Nazis effectively exploited to legitimize their expansionist agenda.

7. Works

- Der deutsche Anteil an der geographischen Erschließung Japans und des subjapanischen Erdraumes und deren Förderung durch Krieg und Wehrpolitik (German contribution to the geographical exploration of Japan and the sub-Japanese area and its promotion through war and military policy) (1913)

- Dai Nihon: Betrachtungen über Gross-Japans Wehrkraft, Weltstellung und Zukunft (Greater Japan: Reflections on Greater Japan's Military Strength, World Position, and Future) (1913)

- Das Japanische Reich in seiner geographischen Entwicklung (The Japanese Empire in its Geographical Development) (1921)

- Japan und die Japaner (Japan and the Japanese) (1923)

- Südostasiens Wiederaufstieg zur Selbstbestimmung (Southeast Asia's Resurgence to Self-Determination) (1923)

- Geopolitik des Pazifischen Ozeans: Studien über die Wechselbeziehungen zwischen Geographie und Geschichte (Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean: Studies on the Interrelations between Geography and History) (1924)

- Grenzen in ihrer geographischen und politischen Bedeutung (Borders in their Geographical and Political Significance) (1927)

- Bausteine zur Geopolitik (Building Blocks of Geopolitics) (1928)

- Japans Reichserneuerung von der Meiji-Ära bis heute (Japan's Reich Renewal from the Meiji Era to Today) (1930)

- Geopolitik der Pan-ideen (Geopolitics of Pan-Ideas) (1931)

- Jenseits der Großmächte (Beyond the Great Powers), edited by Karl Haushofer (1932)

- Der nationalsozialistische Gedanke in der Welt (The National Socialist Idea in the World) (1933)

- Japans Werdegang als Weltmacht und Empire (Japan's Development as a World Power and Empire) (1933)

- Mutsuhito - Kaiser von Japan (Mutsuhito - Emperor of Japan) (1933)

- Weltpolitik von heute (World Politics Today) (1934)

- Raumüberwindende Mächte (Powers Overcoming Space) (1934)

- Napoleon I. (1935)

- Kitchener (1935)

- Foch (1935)

- Die Großmächte vor und nach dem Weltkrieg (The Great Powers Before and After the World War), co-authored with Rudolf Kjellén, and co-edited with Hugo Hassinger and Erich Obst (1935)

- Weltmeere und Weltmächte (World Oceans and World Powers) (1937)

- Welt in Gärung. Zeitberichte deutsche Geopolitiker (World in Ferment. Contemporary Reports by German Geopoliticians), co-edited with Gustav Fochler-Hauke (1937)

- Deutsche Kulturpolitik im indopazifischen Raum (German Cultural Policy in the Indo-Pacific Region) (1939)

- Geopolitische Grundlagen (Geopolitical Foundations) (1939)

- Japan baut sein Reich (Japan Builds Its Empire) (1941)

- Das Werden des deutschen Volkes: Von der Vielfalt der Stämme zur Einheit der Nation (The Becoming of the German People: From the Diversity of Tribes to the Unity of the Nation) (1941)

- Der Kontinentalblock: Mitteleuropa, Eurasien, Japan (The Continental Bloc: Central Europe, Eurasia, Japan) (1941)

- Wehr-Geopolitik: Geographische Grundlagen einer Wehrkunde (Defense Geopolitics: Geographical Foundations of Military Science) (1941)

- Das Reich: Großdeutsches Werden im Abendland (The Reich: Greater German Becoming in the Occident) (1943)

- De la géopolitique (On Geopolitics) (1986)

- English Translation and Analysis of Major General Karl Ernst Haushofer's Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean: Studies on the Relationship between Geography and History (2002)

8. Honors

- Japan: Order of the Sacred Treasure, Second Class (1936)