1. Overview

Count István Széchenyi de Sárvár-Felsővidék (sárvár-felsővidéki gróf Széchenyi Istvánshar-var-FEL-sheh-vee-DAY-kee grohf SAY-chen-yee EESH-tvahnHungarian), born on September 21, 1791, and passing away on April 8, 1860, was a highly influential Hungarian politician, political theorist, and writer. Widely recognized as one of the most significant statesmen in Hungarian history, he is affectionately known within Hungary as "the Greatest Hungarian." Széchenyi dedicated his life to the modernization and national development of Hungary within the framework of the Habsburg monarchy. His vision emphasized gradual, careful reform, advocating for the abolition of feudal privileges and the development of crucial infrastructure, contrasting with more radical approaches of his contemporaries. His multifaceted contributions, ranging from cultural and academic institutions like the Hungarian Academy of Sciences to grand engineering projects such as the Chain Bridge and Danube river regulation, have left an indelible mark on the nation's progress and identity.

2. Family and Early Life

István Széchenyi's background was rooted in one of Hungary's most ancient and influential noble families, traditionally loyal to the House of Habsburg. His early life, military service, and extensive travels laid the groundwork for his future as a leading reformer.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Széchenyi was born in Vienna, the capital of the Austrian Empire, on September 21, 1791. He was the youngest of five children (two daughters and three sons) born to Count Ferenc Széchényi and Countess Juliána Festetics de Tolna. The Széchenyi family was deeply connected with other prominent noble houses, including the Liechtenstein, the House of Esterházy, and the House of Lobkowicz. His father, Ferenc Széchényi, was an enlightened aristocrat who made significant cultural contributions, founding the Hungarian National Museum and the Hungarian National Library. István Széchenyi spent his childhood both in Vienna and on the family's estate in Nagycenk, Hungary. Despite his Hungarian heritage, German was the primary language spoken in his household during his upbringing. He received a private education, which prepared him for a military career.

2.2. Military Service in the Napoleonic Wars

At the age of seventeen, after completing his private education, Széchenyi joined the Austrian army and actively participated in the Napoleonic Wars. He distinguished himself through courageous actions. At the Battle of Raab on June 14, 1809, he fought with valor. On July 19, he risked his life to deliver a crucial message across the Danube River to General Johann Gabriel Chasteler de Courcelles, facilitating the junction of two Austrian armies.

His military career also included a memorable ride through enemy lines on the night of October 16-17, 1813. This daring mission was to convey the wishes of the two emperors to Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher and Bernadotte, urging their participation in the Battle of Leipzig the following day at a specified time and location. In May 1815, he was transferred to Italy. At the Battle of Tolentino, he famously scattered Joachim Murat's bodyguards with a bold cavalry charge. He left military service in 1826 as a captain, after his application for promotion to major was declined, subsequently dedicating his attention to political affairs.

3. Political Career and Reform Activities

Upon leaving military service, István Széchenyi embarked on a transformative political career, driven by a profound commitment to modernize Hungary. His reformist vision aimed to address the nation's feudal anachronisms and propel it towards European standards of development.

3.1. European Travels and Early Influences

Between September 1815 and 1821, Széchenyi undertook extensive travels across Europe, visiting countries such as France, England, Italy, Greece, and the Levant. During these journeys, he meticulously studied the institutions and advancements of these nations. He also forged important personal connections that would prove valuable in his later endeavors. The rapid modernization, particularly the Industrial Revolution, in Britain profoundly fascinated him and significantly shaped his reformist ideas. He was also deeply impressed by engineering feats such as the Canal du Midi in France, which inspired him to envision similar improvements for navigation on Hungary's major rivers, the lower Danube and Tisza. These experiences instilled in him a keen awareness of the growing disparity between modern Europe and his native Hungary, fueling his determination to instigate comprehensive reforms.

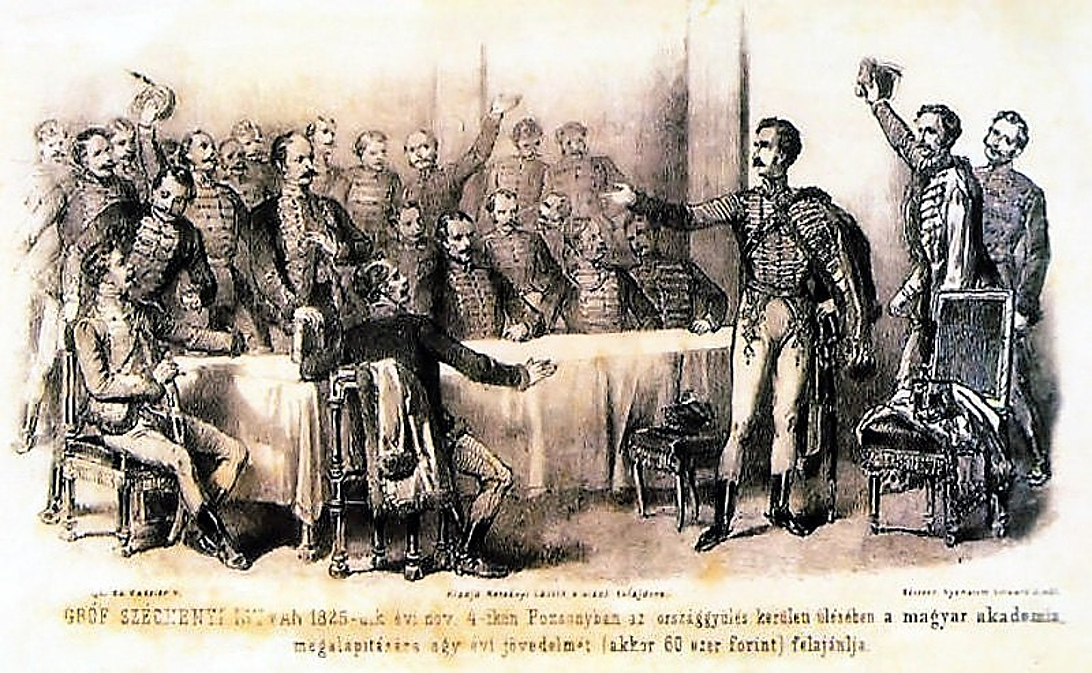

3.2. Founding of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

A pivotal moment in Széchenyi's reform activities occurred in 1825 when he passionately supported the proposal by Pál Nagy, the representative of Sopron county, to establish the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Demonstrating his unwavering commitment, Széchenyi donated his entire annual income for that year, a sum of 60.00 K HUF, towards the foundation and endowment of the Academy. His remarkable generosity inspired other wealthy nobles, who collectively contributed an additional 58.00 K HUF. This collective effort secured royal approval for the Academy's establishment. Széchenyi's primary motivation was to promote the use and development of the Hungarian language, which he saw as crucial for national identity and scholarship. He became the Academy's first Vice-President, with the Palatine serving as its President. In his inaugural address as Vice-President, Széchenyi articulated a broader vision, reminding his countrymen of their duty to support other nations theoretically under the "crown of St. Stephen" (including Croats, Czechs, and Slovaks) in their own pursuits of "sound nationalism." This initiative marked a significant milestone both in his personal journey and for the burgeoning reform movement in Hungary.

3.3. National Casino

In 1827, Széchenyi organized the Nemzeti Kaszinó, or National Casino. This institution served as an exclusive forum for the patriotic Hungarian nobility, providing a vital venue for political dialogue and the exchange of reformist ideas during a critical period of national awakening. The National Casino played a significant role in fostering intellectual discourse and consolidating support for the reform movement among the influential elite.

3.4. Key Writings and Political Thought

To disseminate his reformist ideas to a broader audience, Széchenyi published a series of influential political writings. His notable works include Hitel (Credit, 1830), Világ (World/Light, 1831), and Stádium (1833). These publications were primarily addressed to the Hungarian nobility, whom he criticized for their conservatism. Széchenyi passionately urged them to relinquish their feudal privileges, such as their exemption from taxation, and to instead embrace their role as the driving elite for Hungary's modernization. His writings were instrumental in articulating his vision for social and economic transformation, laying the theoretical groundwork for the reform era. Later in his life, he also authored Önismeret (Self-awareness), a book focusing on children, education, and pedagogy, and Ein Blick (One Look), a study analyzing Hungary's profound political challenges in the early 1850s.

3.5. Infrastructure and Transportation Development

Széchenyi placed significant emphasis on the development of transportation infrastructure, recognizing its crucial importance for economic growth and communication. In 1835, in collaboration with the Austrian shipping company Erste Donaudampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft (DDSG), he established the Óbuda Shipyard on Hajógyári Island in Hungary. This marked a significant milestone as it was the first industrial-scale steamship building company in the Habsburg Empire.

His comprehensive program included the regulation of the lower Danube River's water flow to enhance navigation. This ambitious project aimed to open the river to commercial shipping and trade, creating a continuous route from Buda to the Black Sea. By the early 1830s, Széchenyi became the leading figure of the Danube Navigation Committee, which successfully completed its work within ten years. Before these efforts, the Danube had been perilous for ships and an inefficient international trading route. Széchenyi was a pioneer in promoting the use of steamboats on the Danube, the Tisza, and Lake Balaton, thereby opening Hungary to increased trade and development. Recognizing the project's regional potential, he successfully lobbied in Vienna to secure Austrian financial and political support and was appointed high commissioner, overseeing the works for several years. During this period, he traveled to Constantinople and established important relations in the Balkan region.

Széchenyi also championed the development of Buda and Pest as the major political, economic, and cultural center of Hungary. He notably supported the construction of the Chain Bridge, the first permanent bridge connecting the two cities. Beyond its practical role in improving transportation, the Chain Bridge held profound symbolic significance, foreshadowing the later unification of Buda and Pest into Budapest, thereby connecting the cities rather than letting the river divide them.

3.6. Vision within the Habsburg Monarchy

István Széchenyi's strategic approach to reform was firmly rooted within the existing framework of the Habsburg monarchy. He was convinced that Hungary's initial development required a gradual economic, social, and cultural evolution. Consequently, he strongly opposed both undue radicalism and extreme nationalism. Széchenyi viewed nationalism as particularly perilous within the multi-ethnic Kingdom of Hungary, where various populations were already divided by ethnicity, language, and religion. His vision prioritized incremental progress and stability, believing that a harmonious relationship with the Habsburg dynasty was essential for Hungary's long-term prosperity and reform success.

4. Political Rivalry with Kossuth

The period leading up to the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was marked by a significant intellectual and political rivalry between István Széchenyi and Lajos Kossuth. Their differing ideologies and approaches to national reform became the subject of extensive public debate.

4.1. "Long Debate" of Reformers in the Press

From 1841 to 1848, Széchenyi and Kossuth engaged in a prominent publicistic debate, often referred to as the "Long Debate," through pamphlets and newspapers. In his 1841 pamphlet, Kelet Népe (People of the East), Széchenyi articulated his response to Kossuth's reform proposals. Széchenyi advocated for economic, political, and social reforms to proceed slowly and with extreme caution, primarily to avert the potentially disastrous interference of the Habsburg dynasty, which he feared would violently suppress any radical movements. He was acutely aware of the widespread appeal of Kossuth's ideas within Hungarian society but believed that Kossuth overlooked the crucial need to maintain a constructive relationship with the Habsburgs.

Kossuth, conversely, rejected the traditional role and primacy of the aristocracy, actively questioning established norms of social status. Unlike Széchenyi, Kossuth believed that in the process of social reform, it would be impossible to confine civil society to a passive role. He cautioned against attempts to exclude broader social movements from political life and championed democracy, advocating against the dominance of elites and the government. In 1885, Kossuth characterized Széchenyi as a liberal elitist aristocrat, while Széchenyi viewed Kossuth as a democrat. Széchenyi's political stance was largely isolationist, whereas Kossuth regarded strong relations and collaboration with international liberal and progressive movements as indispensable for achieving liberty.

4.2. Economic and Political Ideologies

Their ideological differences extended to economic policy. Széchenyi based his economic vision on the laissez-faire principles he observed in the British Empire. He sought to preserve Hungary's traditionally strong agricultural sector as the economy's main characteristic. In stark contrast, Kossuth supported protective tariffs to bolster Hungary's comparatively weak industrial sector. Kossuth envisioned the rapid industrialization of the country, while Széchenyi advocated for a more gradual, agriculture-focused economic development. These fundamental differences in economic and political philosophies underscored the deep divide between their respective approaches to Hungary's modernization.

5. Marriage and Family

In 1836, at the age of 45, István Széchenyi married Countess Crescencia von Seilern und Aspang in Buda. Together, they had three children:

- Júlia Széchenyi, who tragically died at the age of three months.

- Béla Széchenyi, who became known for his extensive travels and explorations. He ventured multiple times to countries in the East Indies, Japan, China, Java, Borneo, western Mongolia, and the frontiers of Tibet. In 1893, he published an account of his experiences, written in German.

- Ödön Széchenyi, who later became a pasha in the Turkish service.

6. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and Mental Health

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 marked a turning point in Széchenyi's life. The revolution's trajectory, which aimed for Hungary's complete break from Habsburg rule, ran contrary to his cautious approach and his vision for Hungary's future within the monarchy. In March 1848, despite his apprehensions about revolutionary disruption, he accepted the portfolio of Ways and Communications in the first responsible Magyar administration under Lajos Batthyány. However, the escalating political turmoil and the growing intensity of the revolution deeply affected him.

In early September 1848, Széchenyi's mental state deteriorated, leading to severe depression and a breakdown. His physician ordered him to the private asylum of Dr. Gustav Görgen in Oberdöbling, near Vienna, where he was admitted for treatment. With the devoted care of his wife, he gradually recovered enough to resume writing, producing works such as Önismeret and Ein Blick, which analyzed Hungary's deep political problems in the early 1850s. However, he never returned to active political life. His mental health struggles became a profound symbol of the psychological toll that the political upheavals of the time took on a deeply committed reformer. In 1859, a pamphlet criticizing the Habsburgs' absolutist rule in Hungary was published, and Széchenyi was threatened with charges of treason, further exacerbating his condition.

7. Death

Still suffering from chronic depression and facing the threat of charges for his critical writings against the Habsburg absolutist government, István Széchenyi committed suicide by a gunshot to his head on April 8, 1860, in Vienna. He was 68 years old. Notably, April 8 was the anniversary of the death of the Hungarian national hero Francis II Rákóczi, a century earlier.

His death was met with widespread national mourning throughout Hungary. The Hungarian Academy of Sciences officially entered a period of mourning, as did many prominent figures from leading political and cultural associations, including counts József Eötvös, János Arany, and Károly Szász. Even his political rival, Lajos Kossuth, paid tribute to him, declaring him "the greatest of the Magyars."

8. Writings

István Széchenyi was a prolific writer whose works were central to the Hungarian reform movement. His major published works include:

- Hitel (Credit, 1830)

- Világ (World/Light, 1831)

- Stádium (1833)

- Kelet Népe (People of the East, 1841)

- Önismeret (Self-awareness)

- Ein Blick (One Look)

Many of his numerous writings on political and economic subjects were translated into German to gain broader recognition across Europe. From 1884 to 1896, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences published a comprehensive nine-volume edition of his collected works in Pest.

9. Legacy and Honors

István Széchenyi's contributions have left a profound and lasting impact on Hungary, leading to widespread public, academic, and international recognition.

9.1. Public Recognition and Memorials

Széchenyi's enduring legacy is commemorated through numerous public memorials and honors across Hungary and beyond. On May 23, 1880, a significant statue dedicated to him was unveiled in Budapest. In the same year, another statue commemorating his achievements was unveiled in Sopron. In 1898, the iconic Chain Bridge over the Danube, which he strongly advocated for, was officially named Széchenyi Lánchíd ("Széchenyi Chain Bridge") in his honor.

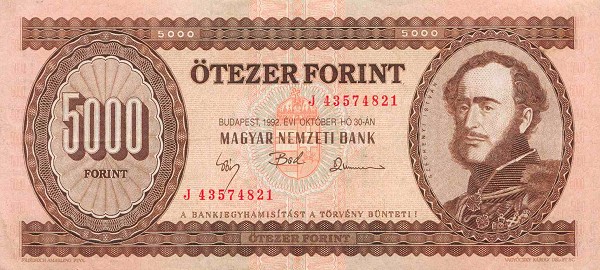

Since 1990, Széchenyi's portrait has been prominently featured on the 5.00 K HUF banknote, with a new design introduced in 1999.

His image has also graced several postage stamps issued by Hungary: on July 1, 1932, as part of the "Famous Hungarians" series; on May 3, 1966, featuring his portrait with the Chain Bridge in the background; and on April 8, 2016, with his face superimposed on the island of the Danube. Further, in 2002, a Hungarian made-for-TV movie titled A HídemberThe BridgemanHungarian (The Bridgeman) portrayed his life from 1820 to 1860. In space, 91024 Széchenyi, an asteroid discovered in 1998 by astronomers Krisztián Sárneczky and László L. Kiss at the Piszkéstető Station, was named in his memory.

9.2. Academic and International Recognition

Széchenyi's influence extends to academic and international spheres, fostering continued study and connections related to his work. In 2008, the István Széchenyi Chair in International Economics was privately endowed at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut, United States. This chair, established in collaboration with the Mathias Corvinus Collegium and Sapientia Hungarian University of Transilvania, oversees and develops three major academic programs aimed at strengthening relations with Central Eastern Europe, particularly Hungary: the Hungarian American Business Leaders (HABL), the Quinnipiac University executive MBA Trip in Hungary, and the Foreign Lecture Series.

9.3. Public Perception

István Széchenyi is highly regarded by the Hungarian public. In a survey conducted by Median and Elemér Hankiss at the end of 2007, the Hungarian public ranked him as the "greatest statesman of all time" among Hungarian historical figures, underscoring his enduring importance in the national consciousness.

9.4. Positive Impact and Contributions

Széchenyi's legacy is overwhelmingly positive, centered on his pivotal role in modernizing Hungary. He is credited with promoting national consciousness through initiatives like the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and fostering significant social and economic development through his advocacy for infrastructural projects, economic reforms, and the abolition of feudal privileges. His vision for a reformed Hungary, while cautious and gradual, laid essential foundations for the nation's progress and its integration into the modern European landscape.

9.5. Criticism and Controversies

Despite his revered status, Széchenyi's political decisions and ideologies have faced some historical scrutiny. His cautious approach and insistence on working within the Habsburg framework led to significant ideological clashes with more radical figures like Lajos Kossuth, who advocated for immediate and complete independence from Austrian rule. Széchenyi viewed Kossuth as a political agitator whose popularity could lead to disastrous conflicts with the Habsburgs. His fears were ultimately realized with the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, which spiraled into a struggle against Habsburg dominance and was brutally suppressed. This intense political turmoil and the deviation of the revolution from his gradualist vision profoundly impacted his mental health, leading to a nervous breakdown in September 1848 and his subsequent withdrawal from public life. Furthermore, his criticism of Habsburg absolutist rule in the late 1850s resulted in threats of treason charges, which contributed to his severe depression and ultimately, his suicide. These aspects highlight the immense personal and political pressures Széchenyi faced while navigating Hungary's path to modernization.