1. Overview

El Salvador, officially the Republic of El Salvador, is the smallest and most densely populated country in Central America. Situated on the Pacific coast of the isthmus, it is bordered by Guatemala to the northwest and Honduras to the northeast and east. The country's geography is characterized by volcanic mountain ranges, a central plateau, and a narrow coastal plain. Its capital and largest city is San Salvador.

Historically, the region was home to Mesoamerican civilizations such as the Maya, Lenca, and Pipil, whose major state was Cuzcatlán. Spanish conquest in the 16th century led to nearly three centuries of colonial rule, profoundly shaping the nation's culture and social structures, primarily based on the exploitation of indigenous labor for cash crops like cacao and indigo. El Salvador gained independence from Spain in 1821, initially as part of the First Mexican Empire and then the Federal Republic of Central America, before becoming a fully sovereign nation in 1841. The 19th and early 20th centuries were marked by political instability, the rise of a coffee-based export economy controlled by a powerful oligarchy, and increasing social stratification.

The 20th century witnessed prolonged periods of military dictatorship, severe political repression, and extreme socio-economic inequality, culminating in the brutal La Matanza massacre of 1932 and later the devastating Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992). This conflict, fought between the U.S.-backed military government and leftist guerrilla groups of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), resulted in an estimated 75,000 deaths and widespread human rights violations. The 1992 Chapultepec Peace Accords ended the war and ushered in an era of multiparty democracy.

Post-war El Salvador has faced significant challenges, including economic reconstruction, addressing deep-rooted social inequities, and combating high levels of crime, particularly gang violence perpetrated by groups like MS-13 and Barrio 18. The political landscape saw a shift from right-wing ARENA party dominance to the election of FMLN presidents, and more recently, the rise of Nayib Bukele and his Nuevas Ideas party. Bukele's administration, beginning in 2019, has implemented a controversial but popular crackdown on gangs, leading to a dramatic reduction in homicide rates but also raising serious concerns about human rights and the erosion of democratic institutions. Economically, El Salvador adopted the U.S. dollar in 2001 and, in a globally unique move, made Bitcoin legal tender in 2021. Remittances from Salvadorans living abroad, primarily in the United States, remain a crucial component of the national economy.

The country's culture is a blend of indigenous traditions and Spanish colonial influences, evident in its language, religion (predominantly Roman Catholic and Protestant), cuisine, and arts. El Salvador continues to grapple with issues of social justice, human rights, and the strengthening of its democratic framework amidst ongoing political and economic transformations.

2. Etymology

The name "El Salvador" is Spanish for "The Savior," a direct reference to Jesus Christ. Following the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century, the territory, particularly the area around the newly founded city of San Salvador (Holy Savior), was named in honor of Jesus. Pedro de Alvarado, a lieutenant of Hernán Cortés, is credited with naming the region.

Initially, the land was divided into provinces. The province of San Salvador, established after the conquest of the Pipil kingdom of Cuzcatlan, was one such division. From 1579, this also included the province of San Miguel (Saint Michael). Throughout the colonial era, San Salvador evolved from an alcaldía mayorgreat mayor's officeSpanish to an intendancy, and finally a province with a provincial council. The province of Izalco, later known as the mayor's office of Sonsonate, was another key jurisdiction.

In 1824, after independence from Spain and the brief incorporation into the First Mexican Empire, these jurisdictions were united to form the State of Salvador, which became part of the Federal Republic of Central America. After the dissolution of this federation in 1841, the country was commonly referred to as the Republic of Salvador (República del SalvadorRepublic of SalvadorSpanish).

In 1915, the Legislative Assembly passed a law officially stipulating that the country's name should be rendered in its definite form: El SalvadorThe SaviorSpanish, rather than simply SalvadorSaviorSpanish. This reaffirmed the religious origin of the name. Another law passed in 1958 further confirmed El SalvadorEl SalvadorSpanish as the official name of the republic.

3. History

The history of El Salvador spans from early human settlements through the rise and fall of indigenous civilizations, the profound impact of Spanish colonization, the struggles of nation-building in the 19th century, the political turmoil and dictatorships of the 20th century, a devastating civil war, and contemporary efforts towards democratic consolidation and social development.

3.1. Prehistoric and Pre-Columbian Era

During the Pleistocene epoch, the territory of present-day El Salvador was inhabited by various megafauna species, now extinct. Fossil evidence indicates the presence of creatures such as the giant ground sloth (Eremotherium), the rhinoceros-like Mixotoxodon, the elephant-relative gomphothere (Cuvieronius), the glyptodont Glyptotherium, the llama-like Hemiauchenia, and the horse Equus conversidens. Human presence in El Salvador likely dates back to the Paleoindian period, supported by the discovery of fluted stone points in western El Salvador.

Archaeological understanding of Pre-Columbian civilization in El Salvador is somewhat limited due to high population density hindering excavations and volcanic eruptions blanketing potential sites. This particularly affects knowledge of the Preclassic Period (roughly 2000 BC - 250 AD) and earlier.

Notable early settlements include Chalchuapa in western El Salvador, first settled around 1200 BC. It grew into a major urban center on the periphery of the Maya civilization during the Preclassic Period, heavily involved in trade networks dealing in ceramics, obsidian, cacao, and hematite. A significant volcanic eruption around 430 AD severely damaged Chalchuapa, and it never fully regained its former prominence. Another important site is Cara Sucia in the far west, which began as a small settlement around 800 BC. During the Late Classic period (600-900 AD), Cara Sucia emerged as a major urban settlement before its abrupt destruction in the 10th century.

The Pipil people, Nahua-speaking groups, migrated from Anahuac (central Mexico) beginning around 800 AD and occupied the central and western regions of El Salvador. They were the last major indigenous group to arrive in the area. The Pipil called their territory KuskatanThe Place of Precious Jewelspip, which was later Hispanicized to Cuzcatlan. This became the largest and most powerful indigenous domain in Salvadoran territory at the time of European contact. The term Cuzcatleco is still used to identify someone of Salvadoran heritage.

While the Pipil dominated the west and center, the eastern part of El Salvador was primarily inhabited by the Lenca. Lenca place names like Intipucá, Chirilagua, and Lolotique are common in this region. Archaeological sites such as Quelepa highlight Lenca cultural presence and connections with Mayan sites like Copán in Honduras.

Other Mayan sites in western El Salvador include Lake Güija and Joya de Cerén. Joya de Cerén, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is often called the "Pompeii of the Americas" because it was a Maya agricultural village remarkably preserved under layers of volcanic ash from an eruption of the Loma Caldera volcano around 600 AD. Cihuatán, another significant site, shows evidence of trade links with northern Nahua cultures, eastern Mayan and Lenca cultures, and indigenous cultures from Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The Tazumal archaeological site, with its Talud-tablero architectural style, particularly in structure B1-2, is associated with Nahua culture and their migration history.

3.2. Spanish Conquest and Colonial Period (1525-1821)

By 1521, the indigenous populations of Mesoamerica had already been significantly impacted by a smallpox epidemic spreading from Mexico, though its full force had not yet reached Cuzcatlán. The first known European visit to what is now Salvadoran territory was by Spanish admiral Andrés Niño in 1522. He landed in the Gulf of Fonseca at Meanguera island, naming it Petronila, and then explored Jiquilisco Bay at the mouth of the Lempa River. The Lenca people of eastern El Salvador were the first indigenous group to encounter the Spanish.

The conquest of Cuzcatlán began in June 1524, led by Pedro de Alvarado, one of Hernán Cortés's principal lieutenants, accompanied by his brother Gonzalo and allied indigenous forces from Mexico, primarily Tlaxcalans. The Spanish were initially disappointed by the lack of gold compared to Mexico or Guatemala. However, they soon recognized the agricultural richness of the volcanic soil, leading the Spanish Crown to grant land under the encomienda system, which effectively established forced labor for the indigenous population.

Alvarado's first incursion met fierce resistance from the Pipil warriors of Cuzcatlán. At Acajutla, the Pipil, equipped with cotton armor and long spears, engaged Alvarado's forces. The battle was bloody, and Alvarado himself was wounded, forcing a Spanish retreat to Guatemala. The Pipil warriors famously responded to Spanish demands for surrender and return of captured weaponry with, "If you want your weapons, come get them."

Subsequent expeditions in 1525 and 1528, led by Gonzalo de Alvarado and others, eventually brought the Pipil under Spanish control, aided by the devastating effects of the smallpox epidemic. In 1525, the city of San Salvador was established, though it was relocated twice before settling in its current location.

In eastern El Salvador, the Lenca people also mounted strong resistance. In 1526, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, another of Pedro Alvarado's relatives, founded the garrison town of San Miguel in Lenca territory. According to oral tradition, a Maya-Lenca princess named Antu Silan Ulap I organized a unified Lenca resistance, driving the Spanish out of San Miguel and destroying the garrison. For about ten years, the Lenca successfully prevented permanent Spanish settlement. Lempira, a notable Lenca chieftain who reportedly mocked the Spanish by wearing their captured clothes and using their weapons, continued the fight for several more years until he was killed in battle. After his death, Lenca resistance waned, and the Spanish re-established San Miguel in 1537.

During the colonial period, El Salvador was part of the Captaincy General of Guatemala, an administrative division of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, ruled from Mexico City. However, New Spain exercised little direct control over the daily affairs of the isthmus. The territory that would become El Salvador was administered primarily through the Intendancy of San Salvador, established in 1786, and the mayoralty of Sonsonate. The colonial economy was based on agriculture, initially focusing on cacao production, centered in Izalco, and balsam from the regions of La Libertad and Ahuachapán. Later, indigo plant cultivation for dye became the dominant cash crop. The socio-economic structure was characterized by a small Spanish elite controlling vast lands and indigenous labor, leading to significant social and economic disparities. Indigenous populations faced exploitation, disease, and cultural suppression, though forms of resistance, both overt and subtle, persisted throughout the colonial era.

3.3. Independence (1821)

By the early 19th century, a combination of internal and external factors fueled the desire for independence among Central American elites. Internally, local Creoles (Spaniards born in the Americas) sought greater political and economic control, free from Spanish interference. Externally, the success of the American Revolution and the French Revolution, coupled with the weakening of Spanish royal power due to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, provided both inspiration and opportunity.

In El Salvador, early calls for independence emerged with the 1811 Independence Movement. On November 5, 1811, priest José Matías Delgado rang the bells of the Iglesia La Merced in San Salvador, calling for insurrection. This uprising, along with another in 1814, was suppressed by Spanish authorities, and many leaders were arrested.

As unrest grew throughout the region, Spanish authorities in Guatemala eventually capitulated, signing the Act of Independence of Central America on September 15, 1821. This act declared independence from Spain for the entire Captaincy General of Guatemala, which included the territories that would become Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the Mexican state of Chiapas.

Shortly after, in early 1822, the authorities of the newly independent Central American provinces, meeting in Guatemala City, voted to join the First Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide. El Salvador, however, resisted this annexation, insisting on autonomy for the Central American countries. A Mexican military detachment marched to San Salvador and suppressed the dissent. When Iturbide's empire collapsed in March 1823, the Mexican forces withdrew.

The Central American provinces then seceded from Mexico and, in July 1823, formed the Federal Republic of Central America (initially called the United Provinces of Central America). Manuel José Arce, a Salvadoran, became its first president. This federation was plagued by internal divisions and conflicts between liberal and conservative factions. El Salvador, often a liberal stronghold, clashed frequently with conservative Guatemala. The federation ultimately dissolved in 1838-1841. El Salvador formally declared its full sovereignty on January 30, 1841, after the federation's collapse. Even after becoming a sovereign nation, El Salvador briefly attempted to revive regional unity, forming a short-lived union with Honduras and Nicaragua called the Greater Republic of Central America from 1896 to 1898, but this effort also failed.

3.4. 19th Century

The 19th century in El Salvador, following full independence in 1841, was characterized by significant political turmoil, efforts towards national stabilization, the profound economic and social impact of coffee cultivation, and the consolidation of an oligarchic political system.

The nation-building period was fraught with internal power struggles between liberal and conservative factions, often leading to instability and frequent changes in leadership. Efforts to establish a stable government were hampered by regional conflicts and interventions from neighboring Central American states, each vying for influence or fearing the dominance of others. Figures like Gerardo Barrios, a liberal president, attempted reforms and modernization but faced strong opposition.

Economically, the mid-19th century saw a pivotal shift. As the global market for indigo, previously a key export, declined due to the advent of synthetic dyes, El Salvador turned to coffee cultivation. The volcanic soil proved ideal for coffee, and by the late 19th century, coffee became the dominant cash crop, accounting for the vast majority of export earnings. This "coffee boom" brought significant wealth to the country but also had profound social consequences.

The expansion of coffee plantations led to the concentration of land into the hands of a small, powerful oligarchy-often referred to as the "Fourteen Families" (Catorce FamiliasFourteen FamiliesSpanish), though the actual number varied. This elite controlled not only the economy but also the political system. To facilitate coffee production, communal lands traditionally held by indigenous and peasant communities were often expropriated and privatized. Anti-vagrancy laws were enacted to ensure a compliant labor force for the coffee fincas (plantations), compelling displaced campesinos to work under often harsh conditions.

The development of infrastructure, such as railroads and port facilities (like Acajutla and La Libertad), was primarily geared towards supporting the coffee export economy. While this brought some modernization, the benefits were not widely shared, exacerbating existing social inequalities. The political system remained largely exclusionary, with the coffee oligarchy maintaining power through alliances with the military and control over electoral processes. Rural discontent simmered due to land dispossession and exploitative labor practices, laying the groundwork for social conflicts in the 20th century. The establishment of the National Guard in 1912 as a rural police force was, in part, a measure to protect the interests of the landed elite and suppress any rural unrest.

3.5. 20th Century

The 20th century in El Salvador was a period of profound and often violent transformations, characterized by persistent political instability, the dominance of military dictatorships, significant economic challenges tied to its reliance on coffee exports, and the intensification of social conflicts rooted in extreme inequality, eventually leading to a devastating civil war.

3.5.1. Military Dictatorships and Political Instability

The early 20th century began under the influence of figures like General Tomás Regalado, who took power by force in 1898 and ruled until 1903, reviving the practice of presidents designating their successors. Political stability was fragile, often punctuated by coups and authoritarian rule. The period from 1913 to 1927 was dominated by the Meléndez-Quiñónez dynasty.

The assassination of President Manuel Enrique Araujo in 1913 marked a period of underlying popular discontent. While Arturo Araujo (no relation to Manuel Enrique) won what was considered the country's first freely contested election in 1931, his government lasted only nine months. He faced widespread popular unrest due to unfulfilled promises of economic reform and land redistribution. In December 1931, a coup d'état organized by junior military officers brought General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, Araujo's vice president and minister of war, to power.

Martínez's rule (1931-1944) became one of the most repressive dictatorships in Salvadoran history. His regime was characterized by severe political repression, the suppression of dissent, and the brutal crushing of any opposition. Pro-democracy movements and social resistance, though often met with violence, persisted. Martínez himself was eventually ousted in May 1944 after a general strike.

However, his fall did not end military dominance. The subsequent decades saw a succession of military presidents and juntas, often coming to power through fraudulent elections or coups. Political instability remained chronic, with the military and the landed oligarchy working in tandem to maintain control and resist calls for social and economic reforms. The Christian Democratic Party (PDC) and the National Conciliation Party (PCN) emerged as significant political forces, with the PCN often representing military interests. Efforts by civilian politicians, like José Napoleón Duarte of the PDC, to gain power through democratic means were often thwarted, as seen in the widely disputed 1972 presidential election. This persistent denial of democratic avenues and the ongoing repression fueled growing social unrest and the rise of leftist movements.

3.5.2. La Matanza (1932 Peasant Uprising and Massacre)

In January 1932, a large-scale peasant uprising erupted in the western part of El Salvador, an event that would become a pivotal and traumatic moment in the nation's history. The revolt had deep roots in the socio-economic conditions of the time, particularly the dire poverty of rural peasants, many of whom were indigenous Pipil, and the concentration of land and wealth in the hands of the coffee oligarchy. The Great Depression had exacerbated these hardships, causing coffee prices to plummet and unemployment to soar.

Adding to the economic grievances was political disenfranchisement. The recently installed government of General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez had come to power through a coup in December 1931, and there was widespread discontent over the suppression of democratic freedoms, including the cancellation of the results of the 1932 legislative election.

Social activist and revolutionary leader Farabundo Martí, who had helped found the Communist Party of Central America, played a key role in organizing the uprising, though the extent of communist ideological influence among the largely indigenous peasantry is debated. The rebels, poorly armed primarily with machetes, were led by figures such as Martí and indigenous leader Feliciano Ama. They initially made gains, capturing several towns and cities in western El Salvador and killing an estimated 2,000 people, including landowners and local officials.

The government's response was swift and extraordinarily brutal. General Martínez unleashed the military, which carried out a systematic campaign of suppression that became known as La Matanza ("The Slaughter"). Estimates of the number of people killed by government forces vary widely, ranging from 10,000 to 40,000, with most historians citing figures around 30,000. The vast majority of the victims were Pipil peasants, targeted indiscriminately. Many of the rebellion's leaders, including Feliciano Ama and Farabundo Martí, were captured and executed.

La Matanza had a profound and lasting impact on Salvadoran society. It effectively crushed rural and indigenous organizing for decades and instilled a deep-seated fear of political mobilization. For the indigenous Pipil community, it was a devastating blow, leading to the further erosion of their culture and language as many survivors sought to hide their indigenous identity to avoid persecution. The massacre reinforced the power of the military and the oligarchy and created a legacy of social trauma and resentment that contributed to the political violence and civil war that would engulf the country later in the century.

3.5.3. Football War (1969)

The Football War, also known as the Hundred Hours' War, was a brief but impactful conflict fought between El Salvador and Honduras in July 1969. While the immediate trigger was a series of increasingly tense FIFA World Cup qualifying matches between the two nations, the underlying causes were much deeper, rooted in demographic pressures, land disputes, and economic issues.

El Salvador, the smallest and most densely populated country in Central America, had experienced significant emigration of its citizens to less densely populated Honduras for decades. Many land-poor Salvadorans had settled as squatters on unused or underused land in Honduras, leading to resentment among some Hondurans. By the late 1960s, an estimated 300,000 Salvadorans lived in Honduras.

In 1969, the Honduran government, under pressure from nationalist groups and landowners, began to enforce land reform laws that effectively targeted Salvadoran immigrants, leading to their displacement and expulsion. This created a refugee crisis in El Salvador and heightened tensions between the two countries.

The atmosphere was further inflamed by nationalistic media in both countries during the three-game World Cup qualifying series in June 1969. Riots and violence occurred after each match. Following El Salvador's victory in the decisive third match, diplomatic relations were severed.

On July 14, 1969, the Salvadoran military launched an invasion of Honduras. The Salvadoran army made initial advances, but the Honduran air force proved more effective, bombing Salvadoran airfields and oil facilities. The Organization of American States (OAS) quickly intervened, negotiating a ceasefire that took effect on July 20. Salvadoran troops withdrew in early August under OAS pressure.

The war, though lasting only about four days (or 100 hours), had significant consequences. Casualties numbered in the thousands, mostly civilians. An estimated 60,000 to 130,000 Salvadorans were forcibly expelled or fled from Honduras, exacerbating social and economic problems in El Salvador. Bilateral relations remained strained for over a decade, and commercial ties within the Central American Common Market (CACM) were severely disrupted, contributing to the CACM's decline. The Football War highlighted the deep-seated social and economic issues plaguing the region and contributed to the political instability that would later fuel civil wars in both El Salvador and its neighbors.

3.6. Salvadoran Civil War (1979-1992)

The Salvadoran Civil War was a devastating twelve-year conflict (1979-1992) fought between the military-led government of El Salvador and a coalition of five leftist guerrilla organizations known as the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). The war was rooted in decades of socio-economic inequality, political repression, and the failure of democratic processes.

The political and social roots of the conflict can be traced to the concentration of land and wealth in the hands of a small oligarchy, widespread poverty among the rural peasantry, and a long history of authoritarian military rule that violently suppressed dissent. The 1932 massacre known as La Matanza had crushed earlier peasant uprisings, but social tensions persisted. By the 1970s, various grassroots organizations, including student groups, labor unions, and peasant associations, were demanding reform. The government, often controlled by the military and backed by the oligarchy, responded with increased repression, including harassment, disappearances, and killings by security forces and paramilitary death squads.

The fraudulent 1972 and 1977 presidential elections, which denied victory to opposition candidates, further radicalized many Salvadorans, convincing them that armed struggle was the only path to change. The 1979 coup d'état by reform-minded officers initially offered hope for change, but the ensuing Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG) was unable to control right-wing violence or implement meaningful reforms, and repression continued.

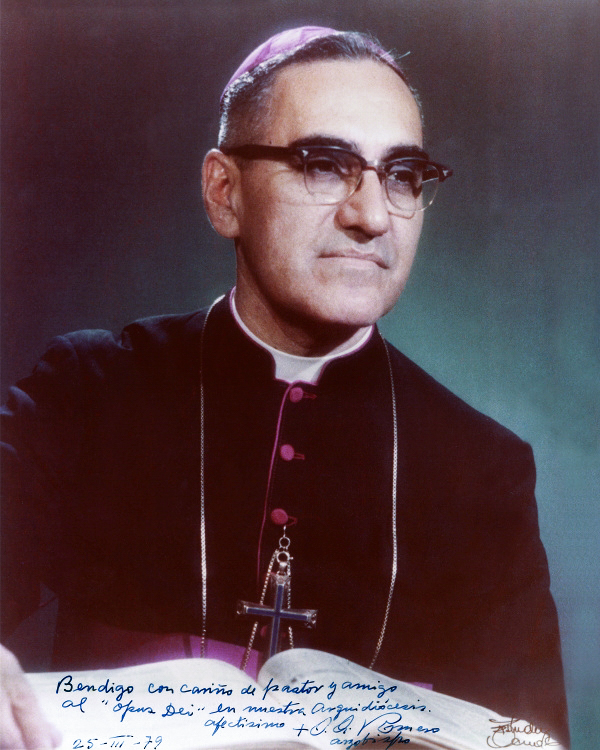

The assassination of Archbishop Óscar Romero on March 24, 1980, while he was celebrating Mass, became a pivotal moment. Romero had been an outspoken critic of government repression and an advocate for the poor. His murder, widely attributed to right-wing death squads, galvanized the opposition and is often considered the spark that ignited the full-scale civil war. In October 1980, various leftist guerrilla groups united to form the FMLN.

The main belligerents were the Salvadoran Armed Forces (FAES), heavily supported and funded by the United States (particularly under the Reagan administration, which viewed the conflict through a Cold War lens as a battle against communism), and the FMLN, which received some support from Cuba and Nicaragua.

The war was characterized by brutal tactics on both sides, but government forces and allied death squads were responsible for the vast majority of human rights violations. These included massacres of civilians, such as the infamous El Mozote massacre in December 1981, where the U.S.-trained Atlácatl Battalion killed hundreds of unarmed men, women, and children. Other notorious incidents included the El Calabozo massacre and the 1989 murder of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter at the Central American University "José Simeón Cañas". Forced disappearances, torture, and extrajudicial killings were widespread. The FMLN also committed human rights abuses, including assassinations and kidnappings, though on a smaller scale.

The conflict caused immense human suffering and societal devastation. An estimated 75,000 to 80,000 people, mostly civilians, were killed. Hundreds of thousands were displaced internally, and over a million Salvadorans fled the country as refugees, primarily to the United States. The economy was shattered, and social trust eroded.

International involvement was significant. The U.S. provided billions of dollars in military and economic aid to the Salvadoran government. Conversely, the FMLN received some support from Cuba, Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, and other leftist groups. The United Nations played an increasingly important role in mediating a peace settlement as the Cold War waned.

Negotiations between the government and the FMLN, facilitated by the UN, culminated in the signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords in Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City, on January 16, 1992. The accords addressed military reforms (including a significant reduction in the armed forces and the dissolution of notorious security units), the creation of a new civilian police force, judicial and electoral reforms, land reform, and the establishment of a Truth Commission to investigate serious acts of violence. The FMLN demobilized its forces and became a legal political party. The civil war formally ended, but its legacy of trauma, social division, and unresolved justice issues continued to affect El Salvador for decades.

3.7. Post-Civil War Era (1992-2019)

The signing of the Chapultepec Peace Accords in January 1992 marked the end of the 12-year civil war and initiated a period of significant transformation in El Salvador. The post-war era focused on democratic consolidation, economic reconstruction, and social integration, though it was also fraught with new challenges, particularly high crime rates and persistent inequality.

Key provisions of the peace accords included substantial military reforms: a significant reduction in the size of the armed forces, the dissolution of notorious security units like the National Police and National Guard, and the creation of a new National Civil Police (PNC) with both ex-military and ex-FMLN personnel. The FMLN transitioned from a guerrilla army into a legitimate political party. Judicial and electoral reforms aimed to strengthen democratic institutions. A Truth Commission was established to investigate wartime atrocities, and its 1993 report detailed widespread human rights violations, attributing the vast majority to state forces. However, a controversial amnesty law passed shortly after the report's release largely shielded perpetrators from prosecution, hindering efforts towards transitional justice and reconciliation.

Politically, the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA), a right-wing party, dominated the presidency from 1989 to 2009, with Alfredo Cristiani (who signed the peace accords), Armando Calderón Sol, Francisco Flores Pérez, and Antonio Saca successively holding office. During this period, El Salvador implemented neoliberal economic reforms, including privatization of state enterprises, trade liberalization (such as ratifying the CAFTA-DR with the United States), and, in 2001, the adoption of the U.S. dollar as its official currency, replacing the colón. These reforms aimed to stabilize the economy and attract foreign investment. While they brought some macroeconomic stability and improved access to international financial markets, benefits were not evenly distributed, and poverty and inequality remained significant problems.

The FMLN gradually gained political strength, becoming the main opposition party. In 2009, Mauricio Funes, a former journalist representing the FMLN, won the presidential election, marking the first time a leftist party had governed El Salvador. His administration focused on social programs and addressing alleged corruption from previous governments. He was succeeded in 2014 by another FMLN leader, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, a former guerrilla commander.

Despite democratic advances, the post-war period was plagued by high levels of crime and violence, largely attributed to the rise of powerful street gangs (maras) like MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha) and Barrio 18. Many gang members had been deported from the United States, bringing gang culture and criminal networks back to El Salvador. The country experienced some of the highest homicide rates in the world, undermining public security and economic development.

Economic reconstruction was slow, and many Salvadorans continued to emigrate, primarily to the United States, seeking economic opportunities and safety. Remittances from these migrants became a crucial part of the national economy.

Challenges during this era included strengthening state institutions, reducing corruption (several former presidents, including Flores and Saca, faced corruption charges), addressing the root causes of violence, and creating inclusive economic growth. While democratic institutions were established, issues of impunity for past human rights abuses and the fragility of the rule of law persisted. The period ended with growing public disillusionment with the traditional political parties (ARENA and FMLN), setting the stage for the rise of a new political figure, Nayib Bukele.

3.8. Nayib Bukele Government (2019-Present)

Nayib Bukele assumed the presidency of El Salvador on June 1, 2019, after winning the 2019 Salvadoran presidential election representing the Grand Alliance for National Unity (GANA) party. His victory marked a significant shift in Salvadoran politics, breaking the three-decade dominance of the two main parties, the right-wing ARENA and the left-wing FMLN. Bukele, a former mayor of San Salvador (initially with the FMLN, then independently), campaigned on an anti-corruption platform and a promise to tackle the country's rampant gang violence.

One of Bukele's most prominent and controversial policies has been his administration's aggressive crackdown on gangs, primarily MS-13 and Barrio 18. Following a significant spike in homicides in March 2022, his government declared a state of emergency, which has been repeatedly extended. This has allowed for the suspension of certain constitutional rights, leading to the mass arrest of tens of thousands of alleged gang members. The crackdown has resulted in a dramatic decrease in homicide rates, with El Salvador, once one of the world's deadliest countries, experiencing its lowest murder rates in decades. This has earned Bukele exceptionally high approval ratings domestically. However, the crackdown has drawn widespread criticism from national and international human rights organizations, citing arbitrary detentions, due process violations, inhumane prison conditions, and deaths in custody. Critics argue that these measures have led to a serious erosion of democratic institutions and civil liberties.

Economically, Bukele's government made international headlines in June 2021 when El Salvador became the first country in the world to adopt Bitcoin as legal tender, alongside the U.S. dollar. The government promoted Bitcoin as a way to reduce remittance costs, boost financial inclusion, and attract investment. The implementation included the creation of a digital wallet called "Chivo" and the installation of Bitcoin ATMs. The move was met with skepticism from international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank due to concerns about Bitcoin's volatility and potential risks for financial stability and consumer protection. The adoption has had mixed results, with limited widespread use among the general population and businesses.

Politically, Bukele's Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas) party, formed after he left GANA, achieved a supermajority in the 2021 legislative elections. This commanding control of the Legislative Assembly allowed his administration to pass laws with little opposition and make significant changes to the judiciary, including the controversial removal and replacement of Supreme Court magistrates and the Attorney General. In September 2021, the new Supreme Court ruled that Bukele could run for a second consecutive term in 2024, a move critics argued violated constitutional prohibitions on immediate re-election.

Bukele was granted a leave of absence in November 2023 to campaign for re-election, with Claudia Rodríguez de Guevara appointed as acting president, the first woman to hold the office in Salvadoran history. On February 4, 2024, Bukele won re-election by a landslide, securing over 80% of the vote in the 2024 Salvadoran general election. His Nuevas Ideas party also retained a dominant majority in the legislature. He was sworn in for his second five-year term on June 1, 2024.

The Bukele administration has been characterized by its effective use of social media for communication and its populist appeal. While supporters credit him with restoring security and challenging a corrupt political establishment, critics express deep concerns about his authoritarian tendencies, the concentration of power, a weakening of checks and balances, lack of transparency, and the long-term impact on human rights and democratic governance in El Salvador. International assessments of his governance are mixed, acknowledging the reduction in violence but cautioning against democratic backsliding.

4. Geography

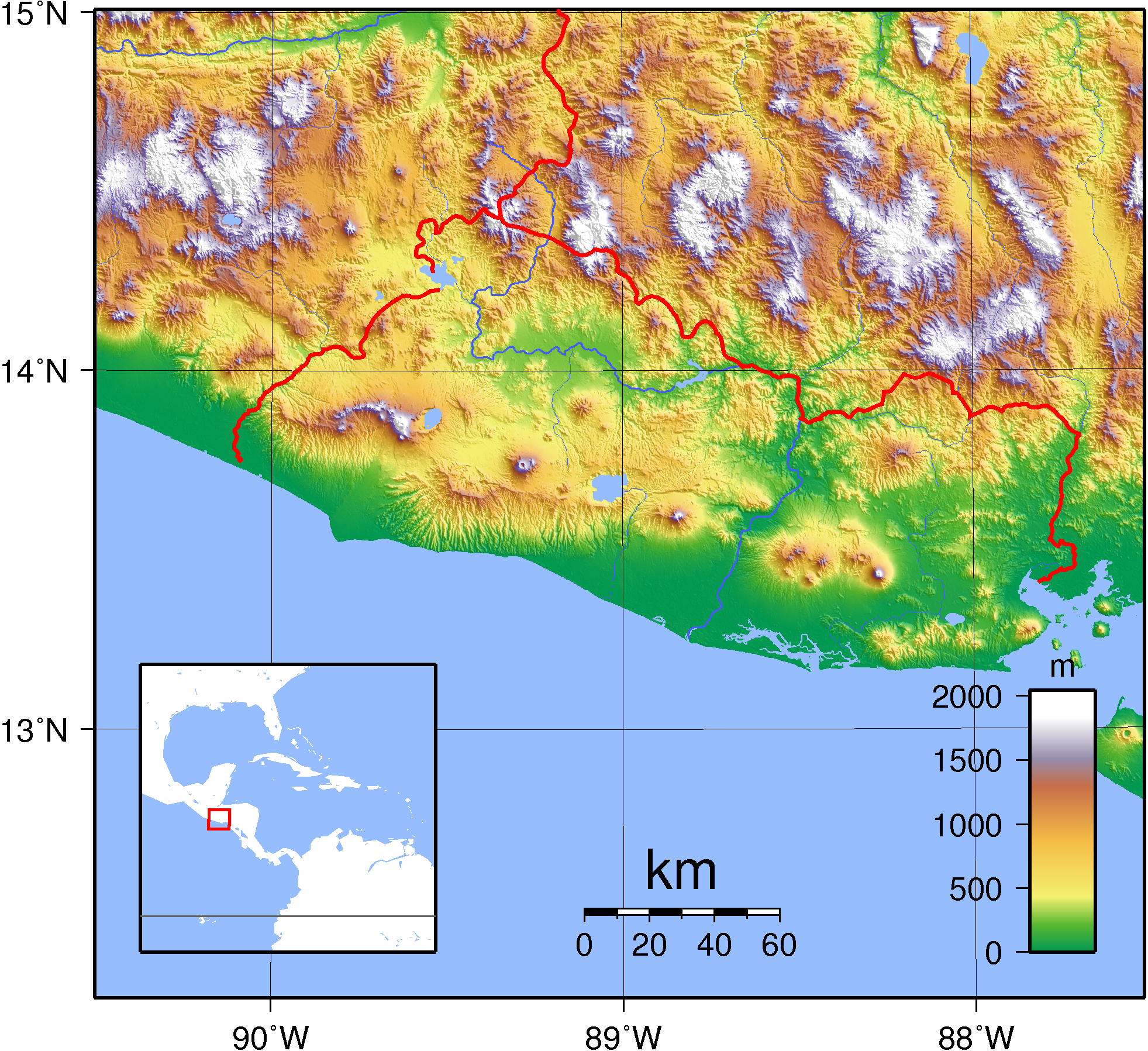

El Salvador is located in the isthmus of Central America. It has a total area of approximately 8.1 K mile2 (21.04 K km2), making it the smallest country in continental America. It is affectionately called Pulgarcito de America (the "Tom Thumb of the Americas") due to its size. The country stretches about 168 mile from west-northwest to east-southeast and 88 mile from north to south.

El Salvador is bordered by Guatemala to the northwest (a border of 126 mile) and Honduras to the northeast and east (a border of 213 mile). It is the only Central American country without a coastline on the Caribbean Sea; its 191 mile coastline is entirely on the Pacific Ocean.

The country's landscape is dominated by two parallel mountain ranges crossing it from west to east, with a central plateau between them, and a narrow coastal plain along the Pacific. These features divide El Salvador into two main physiographic regions: the interior highlands (comprising the mountain ranges and central plateau, covering 85% of the land) and the Pacific lowlands (the coastal plains).

El Salvador has a volcanic geography, situated on the Pacific Ring of Fire. It is home to over 20 volcanoes, many of which are active or potentially active, making it the Central American country with the second-highest number of volcanoes. Notable volcanoes include Santa Ana Volcano (Ilamatepec), the country's tallest volcano at 7.82 K ft above sea level, and San Miguel volcano (Chaparrastique), which is one of the most active. Izalco volcano was famously known as the "Lighthouse of the Pacific" due to its regular eruptions from the early 19th century to the mid-1950s.

The country has over 300 rivers. The most important is the Lempa River (Río Lempa), which originates in Guatemala, flows across the northern mountain range, along much of the central plateau, and then through the southern volcanic range to empty into the Pacific. It is El Salvador's only navigable river for commercial traffic and, along with its tributaries, drains about half of the country's area. Other significant rivers include the Goascorán River, Jiboa River, Torola River, Paz River, and Río Grande de San Miguel.

Several lakes are found in volcanic craters, the most important being Lake Ilopango (approximately 27 mile2 (70 km2)) and Lake Coatepeque (approximately 10 mile2 (26 km2)). Lake Güija, on the border with Guatemala, is El Salvador's largest natural lake (approximately 17 mile2 (44 km2)). Artificial lakes have been created by damming the Lempa River, the largest being the Cerrón Grande Reservoir (Embalse Cerrón Grande, approximately 52 mile2 (135 km2)). The total area of water within El Salvador's borders is 123.6 mile2.

The highest point in El Salvador is Cerro El Pital, at 8.96 K ft, located on the border with Honduras.

4.1. Climate

El Salvador has a tropical climate with pronounced wet and dry seasons. Temperatures vary primarily with elevation and show little seasonal change.

The rainy season, known locally as invierno (winter), extends from May to October. Almost all the annual rainfall occurs during this period. Yearly precipitation totals can be as high as 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm), particularly on southern-facing mountain slopes. Protected areas and the central plateau receive lesser, although still significant, amounts. Rainfall during this season generally originates from low-pressure systems over the Pacific Ocean and usually falls in heavy afternoon thunderstorms. While hurricanes occasionally form in the Pacific, they seldom directly affect El Salvador, with notable exceptions being Hurricane Mitch in 1998 (which formed in the Atlantic) and Hurricane Emily in 1973.

The dry season, known locally as verano (summer), lasts from November through April. During these months, northeast trade winds control weather patterns. Air flowing from the Caribbean loses most of its moisture while passing over the mountains in Honduras. By the time this air reaches El Salvador, it is typically dry, hot, and hazy.

Temperature variations are more dependent on altitude than on the season. The Pacific lowlands are the hottest region, with annual average temperatures ranging from 77 °F (25 °C) to 84.2 °F (29 °C). The central plateau, where the capital San Salvador is located, is more moderate, with an annual average temperature of around 73.4 °F (23 °C); absolute high temperatures can reach 100.4 °F (38 °C) and lows around 42.8 °F (6 °C). Mountainous areas are the coolest, with annual averages ranging from 53.6 °F (12 °C) to 73.4 °F (23 °C), and minimum temperatures occasionally approaching freezing at the highest elevations.

4.2. Natural Disasters

El Salvador's geographical location and geological characteristics make it highly vulnerable to various natural disasters, which have historically caused significant socio-economic damage and loss of life. These include earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, hurricanes, floods, and droughts.

4.2.1. Extreme Weather Events

El Salvador's position on the Pacific Ocean makes it susceptible to severe weather conditions. Heavy rainstorms, often leading to widespread flooding and landslides, are common, particularly during the wet season (May to October). Conversely, the country also experiences severe droughts, which can devastate agriculture. Both phenomena may be exacerbated by the El Niño and La Niña effects.

For example, in the summer of 2001, a severe drought destroyed approximately 80% of El Salvador's crops, leading to famine in rural areas. On October 4, 2005, severe rains associated with Hurricane Stan resulted in dangerous flooding and landslides, causing at least 50 deaths. Hurricane Mitch in 1998, although an Atlantic hurricane that made landfall in Honduras, caused extensive flooding and damage in El Salvador as well.

4.2.2. Earthquakes and Volcanic Activity

Situated along the Pacific Ring of Fire, El Salvador is subject to significant tectonic activity, resulting in frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The capital, San Salvador, has been destroyed or heavily damaged multiple times by earthquakes throughout its history, notably in 1756 and 1854, and suffered significant damage in tremors in 1919, 1982, and 1986.

More recent devastating earthquakes include:

- A magnitude 7.7 earthquake on January 13, 2001, which caused a massive landslide in the Las Colinas neighborhood of Santa Tecla, killing more than 800 people in total across the country.

- Another strong earthquake just a month later, on February 13, 2001 (magnitude 6.6), which killed 255 people and damaged about 20% of the nation's housing.

- A magnitude 5.7 earthquake in 1986 devastated San Salvador, resulting in approximately 1,500 deaths, 10,000 injuries, and 100,000 people left homeless.

El Salvador has over twenty volcanoes, with several being active. San Miguel (Chaparrastique) and Izalco have been active in recent years. Izalco famously erupted with such regularity from the early 19th century to the mid-1950s that it earned the nickname "Lighthouse of the Pacific," as its brilliant flares were visible to ships at sea. The Santa Ana Volcano (Ilamatepec) had a significant eruption on October 1, 2005, spewing ash, hot mud, and rocks that fell on nearby villages, causing two deaths. One of the most catastrophic volcanic events in the region's history was the eruption of the Ilopango volcano in the 5th century AD (around 431 AD or 535/536 AD according to different studies), which had a VEI of 6+. This massive eruption produced widespread pyroclastic flows, devastated Mayan cities, and had significant climatic and demographic impacts across the Maya realm and potentially globally.

4.3. Flora and Fauna

Despite its small size and high population density, El Salvador possesses a notable degree of biodiversity, though its ecosystems have been significantly impacted by human activity, particularly deforestation for agriculture. It is estimated that the country is home to approximately 500 species of birds, 1,000 species of butterflies, 400 species of orchids, 800 species of trees, and 800 species of marine fish.

Key terrestrial ecosystems in El Salvador include Central American montane forests, Sierra Madre de Chiapas moist forests, Central American dry forests, Central American pine-oak forests, and mangrove forests along the coast, such as the Gulf of Fonseca mangroves and Northern Dry Pacific Coast mangroves. The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.06/10, ranking it 136th globally out of 172 countries, indicating significant anthropogenic modification of its forests.

Several national parks and protected areas have been established to conserve biodiversity. The largest and one of the most important is El Imposible National Park, located in the Ahuachapán department. It is a critical habitat for many species, including pumas, ocelots, and numerous bird species. Other significant protected areas include Montecristo National Park (part of the Trifinio Fraternidad Transboundary Biosphere Reserve shared with Guatemala and Honduras), Walter Thilo Deininger Park, and various mangrove ecosystems along the Pacific coast.

El Salvador's marine ecosystems are also important. Of the eight species of sea turtles in the world, six nest on the coasts of Central America, and four are found on the Salvadoran coast: the leatherback sea turtle, the hawksbill sea turtle (critically endangered), the green sea turtle, and the olive ridley sea turtle. Conservation efforts are underway to protect these turtle populations and their nesting sites.

The government established the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MARN) in 1997 to address environmental issues and promote conservation. A general environmental framework law was approved in 1999. Non-governmental organizations like SalvaNATURA play a crucial role in managing protected areas and implementing conservation projects. Despite these efforts, challenges such as deforestation, habitat loss, pollution, and the impacts of climate change continue to threaten El Salvador's flora and fauna.

5. Government and Politics

El Salvador is a presidential representative democratic republic with a multi-party system. The 1983 Constitution is the supreme law of the land, establishing a government with three distinct branches: the executive, the legislative, and the judicial, ensuring a separation of powers. The country has faced significant political transformations, including a long civil war and a subsequent transition to democracy, with ongoing challenges related to institutional strength, human rights, and political polarization.

5.1. Political System

The President of El Salvador is both the head of state and head of government. The president is elected by direct universal suffrage for a single five-year term. Historically, immediate re-election was prohibited by the constitution, but a controversial 2021 Supreme Court ruling, made by judges appointed by President Nayib Bukele's allies, allowed for the possibility of consecutive terms, which Bukele pursued and won in 2024. The president appoints a Cabinet of Ministers and is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of El Salvador.

Legislative power is vested in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of El Salvador (Asamblea Legislativa). The number of deputies (diputados) has varied; as of recent changes, it consists of 60 members, elected by popular vote for three-year terms, with the possibility of re-election. The Assembly is responsible for passing laws, approving the national budget, ratifying treaties, and overseeing the executive branch.

The Judiciary is headed by the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de Justicia), which is composed of 15 magistrates, one of whom serves as its President. Supreme Court magistrates are elected by the Legislative Assembly for nine-year terms, staggered so that one-third are renewed every three years. The judiciary is constitutionally independent, but its autonomy has faced challenges, particularly with recent appointments and dismissals of judges that have raised concerns about the separation of powers.

The electoral system is managed by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo Electoral), which is responsible for organizing and overseeing elections. Voting is universal for citizens aged 18 and older.

5.2. Major Political Parties and Trends

For much of the post-civil war era, Salvadoran politics was dominated by two major parties:

- The Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA): A right-wing party founded during the civil war, ARENA held the presidency from 1989 to 2009. It generally advocates for conservative social policies and free-market economics.

- The Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN): Formed as a coalition of leftist guerrilla groups during the civil war, the FMLN became a legal political party after the 1992 peace accords. It held the presidency from 2009 to 2019. Its ideology has ranged from Marxist-Leninist roots to more social democratic positions.

The traditional two-party dominance was significantly disrupted by the rise of Nayib Bukele. After being expelled from the FMLN, Bukele won the 2019 presidential election under the banner of the Grand Alliance for National Unity (GANA), a smaller center-right party. He subsequently founded his own party, Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas).

- Nuevas Ideas (NI): Founded by Bukele, this party achieved a landslide victory in the 2021 legislative elections, securing a supermajority in the Legislative Assembly. It is characterized by its populist appeal and support for Bukele's agenda, particularly his security policies. It won an even larger majority in the 2024 elections.

Other smaller parties include GANA, the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), and the National Conciliation Party (PCN).

Recent political trends include a high level of popular support for President Bukele, largely due to the dramatic reduction in gang violence under his administration. However, this has been accompanied by significant concerns from domestic critics and international observers about democratic backsliding, the concentration of power in the executive branch, the weakening of checks andbalances, and the erosion of judicial independence and human rights. Key political debates revolve around security policies, economic strategies (including the adoption of Bitcoin), governance, and the state of democratic institutions. Voter turnout and public trust in traditional political institutions had declined prior to Bukele's rise, reflecting a desire for change.

5.3. Foreign Relations

El Salvador maintains diplomatic relations with many countries and is a member of numerous international organizations, including the United Nations (UN) and its specialized agencies, the Organization of American States (OAS), the Central American Integration System (SICA), and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). It actively participates in regional forums like the Central American Security Commission. El Salvador is also a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Historically, El Salvador's foreign policy has been significantly influenced by its relationship with the United States. The U.S. is a major trading partner, a key source of foreign investment, and home to a large Salvadoran diaspora whose remittances are vital to the Salvadoran economy. During the Cold War and the Salvadoran Civil War, the U.S. provided substantial military and economic aid to the Salvadoran government. Relations have generally remained close, though they have faced periods of strain, particularly concerning issues of migration, security cooperation, and, more recently, concerns from the U.S. government regarding democratic governance and human rights under the Bukele administration.

El Salvador has pursued regional integration efforts within Central America. It was a founding member of the Central American Common Market and participates in SICA, which is headquartered in San Salvador. Relations with neighboring countries, particularly Honduras and Guatemala, are crucial for trade, security, and migration management. Historical border disputes, such as the one with Honduras that contributed to the 1969 Football War, have largely been resolved through international adjudication.

The country has sought to diversify its diplomatic and economic ties. In 2018, El Salvador switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan (Republic of China) to the People's Republic of China, a move reflecting a broader trend in Central America and aimed at attracting Chinese investment and cooperation.

El Salvador has contributed to international peacekeeping efforts, having sent troops to UN missions. It is a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. In November 1950, El Salvador notably supported a Tibetan appeal to the UN General Assembly against the annexation of Tibet by China, though the plea was ultimately not taken up by the UN.

The country's foreign policy under President Bukele has sometimes been assertive and unconventional, particularly regarding its adoption of Bitcoin as legal tender, which drew varied reactions from the international community and financial institutions. Stances on international human rights and cooperation often reflect domestic priorities, with a strong emphasis on sovereignty. Challenges in foreign relations include managing migration issues, combating transnational crime, attracting sustainable foreign investment, and navigating complex geopolitical dynamics.

5.4. Military

The Armed Forces of El Salvador (Fuerza Armada de El Salvador - FAES) consist of three main branches: the Salvadoran Army (Ejército Salvadoreño), the Salvadoran Air Force (Fuerza Aérea Salvadoreña - FAS), and the Navy of El Salvador (Fuerza Naval de El Salvador - FNES). The President of El Salvador is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.

As of recent estimates, the total active personnel in the armed forces is around 25,000. The military's budget and equipment have varied over time, with significant U.S. aid during the civil war period. Major equipment includes armored vehicles, artillery, transport aircraft, helicopters, and patrol boats.

Historically, the Salvadoran military played a dominant role in the country's politics for much of the 20th century, with numerous military dictatorships. The Chapultepec Peace Accords of 1992, which ended the civil war, mandated significant reforms to the armed forces. These included a substantial reduction in size, the dissolution of certain intelligence and security units notorious for human rights abuses, a redefinition of its mission to focus on national defense and sovereignty, and its subordination to civilian authority. The accords also led to the creation of a new civilian police force.

In the post-civil war era, the military's primary roles have been national defense, participation in disaster relief operations, and, increasingly, supporting civilian law enforcement in combating crime and gang violence, particularly under the Bukele administration's security crackdown. This expanded domestic role for the military has raised concerns among some human rights organizations about the militarization of public security.

El Salvador has also participated in international peacekeeping operations, contributing troops to UN missions in various countries, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Lebanon. The country has a conscription law, but in practice, recruitment is often voluntary. The defense budget has seen fluctuations, often influenced by security challenges and government priorities.

5.5. Human Rights

The human rights situation in El Salvador has been a significant concern for decades, marked by periods of severe state-sponsored violence during the 20th century, particularly the civil war (1979-1992), and ongoing contemporary challenges.

During the civil war, both government forces and FMLN guerrillas committed human rights abuses, but the UN Truth Commission (1993) attributed the vast majority of violations, including massacres, extrajudicial killings, torture, and forced disappearances, to the state military and allied paramilitary groups. An amnesty law passed in 1993 has largely prevented prosecution for these wartime atrocities, leading to persistent impunity.

In the post-war era, while democratic institutions were established, human rights challenges have continued. Key areas of concern include:

- Women's Rights: El Salvador has one of the strictest abortion bans in the world, with no exceptions for rape, incest, or when the mother's life is at risk. This has led to the imprisonment of women for abortion-related offenses, sometimes for decades under charges of aggravated homicide, even in cases of obstetric emergencies or miscarriages. Gender-based violence, including femicide, remains a serious problem.

- LGBT Rights: Discrimination and violence against LGBT people are widespread. While homosexuality is legal, same-sex marriage is not recognized, and LGBT individuals often face societal prejudice, harassment, and violence, with limited legal protections.

- Freedom of the Press: While media outlets operate, there have been increasing concerns about restrictions on press freedom, including harassment and intimidation of journalists critical of the government, particularly under the Bukele administration. Access to public information has also been an issue.

- Access to Justice and Due Process: The justice system has historically been weak and subject to corruption and political influence. Impunity for crimes, both past and present, is a significant problem.

- Impact of Security Policies on Civil Liberties: The government's aggressive crackdown on gangs since March 2022, conducted under a prolonged state of emergency, has led to a dramatic decrease in homicides but has also resulted in widespread allegations of human rights violations. These include arbitrary detentions (tens of thousands arrested), violations of due process, overcrowding and inhumane conditions in prisons, deaths in state custody, and reports of torture. Human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have expressed grave concerns about the suspension of constitutional guarantees and the potential for mass wrongful imprisonment.

- Enforced Disappearances: Cases of enforced disappearances, though fewer than during the civil war, continue to be reported, sometimes linked to gang activity or, more recently, concerns related to the state of emergency detentions.

- Migrants' Rights: Salvadoran migrants, particularly those attempting to reach the United States, face significant human rights risks, including violence, extortion, and human trafficking.

Government efforts to address human rights concerns have been mixed. While some legal frameworks exist, implementation and enforcement are often weak. Civil society organizations and human rights defenders play a crucial role in documenting abuses and advocating for victims, but they too have faced pressure and harassment. The Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman (Procuraduría para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos - PDDH) is the national human rights institution, but its effectiveness has also been questioned at times due to political pressures or lack of resources.

5.6. Administrative Divisions

El Salvador is a unitary state divided into 14 departments (departamentosdepartmentsSpanish) for administrative purposes. Each department is headed by a governor appointed by the President of the Republic. The departments are:

# Ahuachapán (Capital: Ahuachapán)

# Santa Ana (Capital: Santa Ana)

# Sonsonate (Capital: Sonsonate)

# Chalatenanga (Capital: Chalatenango)

# La Libertad (Capital: Santa Tecla)

# San Salvador (Capital: San Salvador) - The national capital.

# Cuscatlán (Capital: Cojutepeque)

# La Paz (Capital: Zacatecoluca)

# Cabañas (Capital: Sensuntepeque)

# San Vicente (Capital: San Vicente)

# Usulután (Capital: Usulután)

# San Miguel (Capital: San Miguel)

# Morazán (Capital: San Francisco Gotera)

# La Unión (Capital: La Unión)

These 14 departments are further subdivided into municipalities (municipiosmunicipalitiesSpanish). Historically, there were 262 municipalities. However, in June 2023, the Legislative Assembly approved a law reducing the number of municipalities from 262 to 44, effective May 1, 2024. These new, larger municipalities are still contained within the existing 14 departments. Each municipality is governed by a municipal council (consejo municipal) headed by a mayor (alcalde), elected by popular vote. The municipalities are responsible for local services such as waste collection, local road maintenance, public markets, and parks.

The municipalities were historically further divided into cantones (cantons) in rural areas and barrios (neighborhoods) in urban areas, which served as smaller administrative or geographical units but generally lacked their own elected officials. Under the 2023 municipal reform, these former municipalities are now referred to as districts within the new, larger municipalities.

6. Economy

El Salvador's economy has traditionally been agricultural, heavily reliant on coffee exports. In recent decades, it has sought to diversify, with the services sector now contributing the largest share to its GDP. The country has faced significant economic challenges, including the impact of its civil war, natural disasters, high crime rates, and periods of economic instability. Key features of its economy include dollarization, a significant reliance on remittances, and the recent adoption of Bitcoin as legal tender. The perspective on its economy emphasizes social equity and sustainable development challenges.

6.1. Economic Structure and Trends

The Salvadoran economy is classified as a developing, lower-middle-income economy. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity was estimated at 57.95 B USD in 2021.

The sectoral composition of GDP is dominated by the services sector, accounting for approximately 64.1% (2008 est.). This includes retail, tourism, finance, and telecommunications. The industrial sector contributes around 24.7%, encompassing manufacturing (especially textiles and apparel, food processing), construction, and utilities. Agriculture represents about 11.2% of GDP (2010 est.), though it employs a larger share of the labor force, particularly in rural areas. Key agricultural products include coffee, sugar, corn, rice, beans, and shrimp.

Economic growth has fluctuated. After the 1992 peace accords, the country implemented neoliberal reforms, including privatization and trade liberalization, leading to moderate growth. The adoption of the U.S. dollar in 2001 aimed to bring macroeconomic stability. GDP growth averaged 3.2% annually after 1996, with a peak of 4.7% in 2007. However, the economy has been vulnerable to external shocks, such as global recessions and fluctuations in commodity prices. Recent years have seen modest growth, with some recovery post-COVID-19 pandemic.

Inflation has generally been low and stable since dollarization. Unemployment and underemployment remain persistent challenges, contributing to emigration. Income inequality, while having seen some reduction, is still a concern. The country has faced fiscal pressures, and government debt has been a subject of attention from international financial institutions.

6.2. Major Industries

- Agriculture: Historically central to the economy, traditional cash crops like coffee and sugar remain important exports. Coffee, once the backbone of the economy, has faced challenges from price volatility, climate change, and crop diseases. The sector also includes subsistence farming of corn, beans, and sorghum.

- Manufacturing: The apparel industry (maquila) is a significant component, producing clothing for export, primarily to the United States, benefiting from trade agreements like CAFTA-DR. Food processing is another key manufacturing sub-sector. Other industries include beverages, chemicals, and textiles.

- Services: This is the largest and most dynamic sector.

- Tourism: Growing in importance, with attractions including beaches (especially for surfing), volcanoes, archaeological sites, and colonial towns.

- Finance: The banking system is relatively developed.

- Retail and Commerce: A major source of employment.

- Call centers and Business Process Outsourcing (BPO): An emerging area.

Development challenges across these industries include improving productivity, diversifying export markets, enhancing infrastructure, addressing security concerns that affect investment, and promoting sustainable practices.

6.3. Currency

El Salvador's official currency history has seen significant shifts.

The Salvadoran colón (SVC) was the official currency of El Salvador from 1892 until 2001. It was named after Christopher Columbus (Cristóbal ColónChristopher ColumbusSpanish).

In January 2001, El Salvador adopted the United States dollar (USD) as its official currency under the Monetary Integration Law. The colón was allowed to co-circulate with the dollar at a fixed exchange rate of 8.75 colones per dollar, but the dollar quickly became the dominant currency, and colones are no longer in circulation, though prices can sometimes still be quoted in colones for reference. The main objectives of dollarization were to achieve macroeconomic stability, reduce inflation, lower interest rates, and encourage foreign investment by eliminating exchange rate risk. While it brought stability in some areas, the impact on long-term growth and competitiveness has been debated.

In a groundbreaking and controversial move, El Salvador became the first country in the world to adopt Bitcoin (BTC) as legal tender on September 7, 2021. The Bitcoin Law, championed by President Nayib Bukele, mandated that Bitcoin be accepted as a form of payment by all businesses, alongside the U.S. dollar. The government launched a digital wallet called "Chivo" and offered a $30 Bitcoin bonus to citizens who downloaded it. The stated goals included facilitating remittances, promoting financial inclusion for the unbanked population, and attracting foreign investment. The adoption has faced mixed reactions domestically and internationally, with concerns raised by the IMF and World Bank about economic, financial, and regulatory risks associated with Bitcoin's volatility. Uptake by the general population and businesses has been limited.

6.3.1. Bitcoin as Legal Tender

On June 8, 2021, the Legislative Assembly of El Salvador, at the initiative of President Nayib Bukele, passed the Bitcoin Law, making Bitcoin (BTC) an official legal tender in the country, effective September 7, 2021. This made El Salvador the first nation globally to adopt a cryptocurrency as legal tender alongside its existing official currency, the U.S. dollar.

Motivations and Legislative Process:

President Bukele cited several key motivations for the law:

- Reducing the cost of remittances, which constitute a significant portion of El Salvador's GDP. Traditional remittance services often involve high fees.

- Promoting financial inclusion, as a large percentage of Salvadorans lack access to traditional banking services.

- Attracting foreign investment and stimulating economic growth.

- Providing an alternative to the U.S. dollar.

The law was passed rapidly with a supermajority vote from Bukele's Nuevas Ideas party and its allies. It mandates that all economic agents must accept Bitcoin as payment when offered, though with some practical exceptions for those lacking the technology. The government committed to providing infrastructure, such as the "Chivo" digital wallet, and education for its adoption. A 150.00 M USD trust fund was established to facilitate conversions between Bitcoin and U.S. dollars. Foreigners investing 3 Bitcoin in the country were offered permanent residency.

Implementation and Economic/Social Impacts:

The rollout on September 7, 2021, was met with technical glitches in the Chivo wallet and protests from some segments of the population concerned about volatility and the mandatory nature of acceptance.

- Uptake:** While the government offered a 30 USD Bitcoin incentive for downloading the Chivo wallet, widespread, sustained use of Bitcoin for daily transactions has been limited. Surveys indicated that a majority of businesses were not actively using Bitcoin, and many citizens cashed out their initial bonus quickly.

- Remittances:** Some increase in Bitcoin remittances was observed, but they remained a small fraction of total remittances, which are still predominantly sent through traditional channels.

- Volatility:** The price volatility of Bitcoin has been a major concern. The value of the government's Bitcoin holdings has fluctuated significantly, leading to questions about the financial risk to public funds.

- Economic Impact:** The overall impact on economic growth and investment is still being assessed and is subject to debate. The move did not immediately lead to the large-scale foreign investment hoped for by proponents.

- Social Impact:** Concerns persist about the digital divide, as access to smartphones and reliable internet is not universal, potentially excluding vulnerable populations. There were also concerns about potential use for illicit finance.

International Reactions:

The international community reacted with a mix of curiosity and concern.

- Financial Institutions:** The International Monetary Fund (IMF) urged El Salvador to reverse its decision, citing risks to financial stability, financial integrity, consumer protection, and fiscal contingent liabilities. The World Bank also declined to assist with the implementation due to environmental and transparency concerns.

- Credit Rating Agencies:** Some credit rating agencies expressed concerns that the Bitcoin adoption could negatively impact El Salvador's ability to secure an IMF loan and increase its financial risks.

- Cryptocurrency Community:** Many in the global cryptocurrency community lauded the move as a historic step towards mainstream adoption of Bitcoin.

President Bukele remained a staunch advocate, announcing plans for "Bitcoin City," a tax-haven city powered by geothermal energy from a volcano, to be financed by Bitcoin-backed bonds, though this project has seen slow progress. As of May 2024, the Bitcoin Office of El Salvador reported government holdings of 5,750 bitcoin, with some mined using geothermal energy. The long-term effects of this policy on El Salvador's economy and society remain a subject of ongoing observation and analysis.

6.4. Energy

El Salvador's energy sector relies on a mix of sources for electricity production, including fossil fuels, hydroelectric power, geothermal energy, solar power, and biomass. The country also imports petroleum for transportation and other energy needs.

Electricity Generation Mix:

El Salvador has made significant strides in diversifying its energy matrix and increasing the share of renewable sources.

- Renewable Energy:** A substantial portion of El Salvador's electricity comes from renewables.

- Hydroelectricity: Historically a major source, with several dams on the Lempa River and other rivers. In January 2021, hydroelectric plants accounted for about 28.5% of injections.

- Geothermal Energy: El Salvador is a pioneer in geothermal energy due to its volcanic geography. It contributes significantly to the electricity supply, accounting for about 27.3% in January 2021. The country aims to use geothermal energy for Bitcoin mining as well.

- Biomass: Utilizes agricultural residues, particularly from sugar cane (bagasse), contributing around 24.4% in January 2021.

- Solar Power: Increasingly important, with photovoltaic solar contributing about 10.6% in January 2021.

- Wind Power: Has started to contribute to the grid, with projects like the Ventus wind park in Metapán. Wind power accounted for about 3.6% in January 2021.

- Fossil Fuels:** Thermal plants using imported fossil fuels (primarily heavy fuel oil and diesel) still play a role, especially to meet peak demand or during dry seasons when hydroelectric output is lower.

In total, renewable sources accounted for over 80% of generation in 2020 and 84.3% by August 2021, according to the National Energy Commission. The installed capacity was around 1,983 MW as of 2021.

Energy Consumption and Supply Network:

The country has a national electricity grid, and efforts have been made to expand electrification to rural areas. The electricity market has undergone reforms, with private sector participation in generation and distribution. El Salvador is also part of the Central American Electrical Interconnection System (SIEPAC), which allows for cross-border electricity trade with neighboring countries.

Policies for Renewable Energy Development:

The government has actively promoted renewable energy through various policies and incentives to reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels, mitigate climate change, and enhance energy security. This includes auctions for renewable energy contracts and support for geothermal and solar projects. The development of geothermal resources is a particular focus, given the country's significant potential.

6.5. Telecommunications and Media

El Salvador's telecommunications sector has seen significant development, with widespread mobile phone penetration and growing internet access. The media landscape includes a mix of state-owned and private outlets.

Telecommunications:

- Mobile Networks:** Mobile cellular subscriptions far exceed the number of fixed-line telephones, with approximately 9.4 million mobile subscriptions reported. Smartphones are common, providing a primary means of internet access for much of the population. Major mobile operators include Tigo, Claro, Digicel, and Movistar (Telefónica, though its operations have been acquired by other companies in some Central American markets). The government has promoted mobile penetration, and testing for 5G coverage began around 2020.

- Fixed Lines:** There are around 900,000 fixed telephone lines.

- Internet:** Internet penetration has been growing, with around 500,000 fixed broadband lines. However, mobile broadband is a more common access method. Public Wi-Fi initiatives have also been launched.

- Regulation:** The sector is regulated, with policies aimed at promoting competition and infrastructure development.

Media:

- Broadcast Media:** There are numerous privately owned national television networks and radio stations. The government also operates one broadcast station. Cable television is widely available and includes international channels. The transition from analog to digital television broadcasting was undertaken, adopting the ISDB-T standard around 2018.

- Print Media:** Several daily newspapers operate, including prominent ones like La Prensa Gráfica and El Diario de Hoy. There are also various magazines and periodicals.

- Online Media:** Online news portals and digital media outlets have become increasingly important sources of information. Social media platforms are widely used for news consumption and public discourse.

Media Freedom and Access to Information:

The state of media freedom in El Salvador has been a subject of concern, particularly in recent years. While the constitution provides for freedom of expression, journalists and media outlets critical of the government have reported facing harassment, intimidation, restricted access to information, and accusations of bias. Organizations monitoring press freedom have noted a decline in the environment for independent journalism. Access to public information has also been an area of concern, with critics pointing to a lack of transparency in some government operations. These issues are crucial for democratic accountability and the public's right to be informed.

6.6. Tourism

Tourism is a significant and growing sector of the Salvadoran economy, contributing to GDP and employment. The country offers a variety of attractions, though its tourism landscape is somewhat different from that of some larger Central American neighbors, with a strong emphasis on its Pacific coastline, volcanic landscapes, and cultural heritage. In 2014, El Salvador received an estimated 1,394,000 international tourists. In 2019, tourism contributed 2.97 B USD to El Salvador's GDP, representing 11% of the total. It directly supported 80,500 jobs in 2013 and indirectly supported 317,200 jobs (11.6% of total employment) in 2019.

Main Tourist Attractions:

- Beaches and Surfing:** El Salvador's Pacific coast is renowned for its surfing spots, attracting surfers from around the world. Popular beaches include El Tunco, Punta Roca (a world-class surf break), El Sunzal, El Zonte, Costa del Sol, and El Majahual. These areas offer a range of accommodations and surf-related services.

- Volcanoes:** The country's volcanic geography provides opportunities for hiking and scenic views. Frequently visited volcanoes include the Santa Ana Volcano (Ilamatepec), Izalco volcano, and El Boquerón (San Salvador volcano) with its large crater. National parks like Cerro Verde offer access to these volcanic areas.