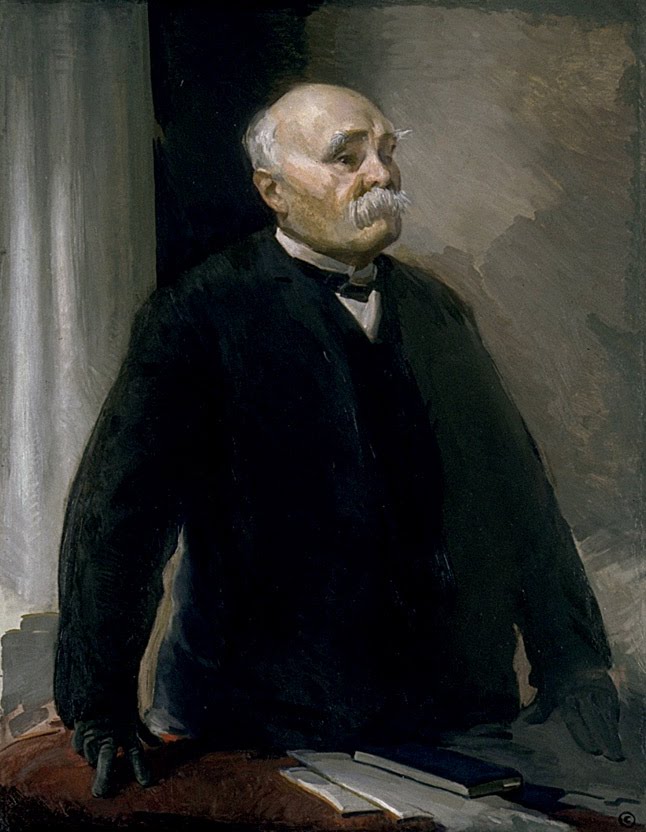

1. Early Life and Background

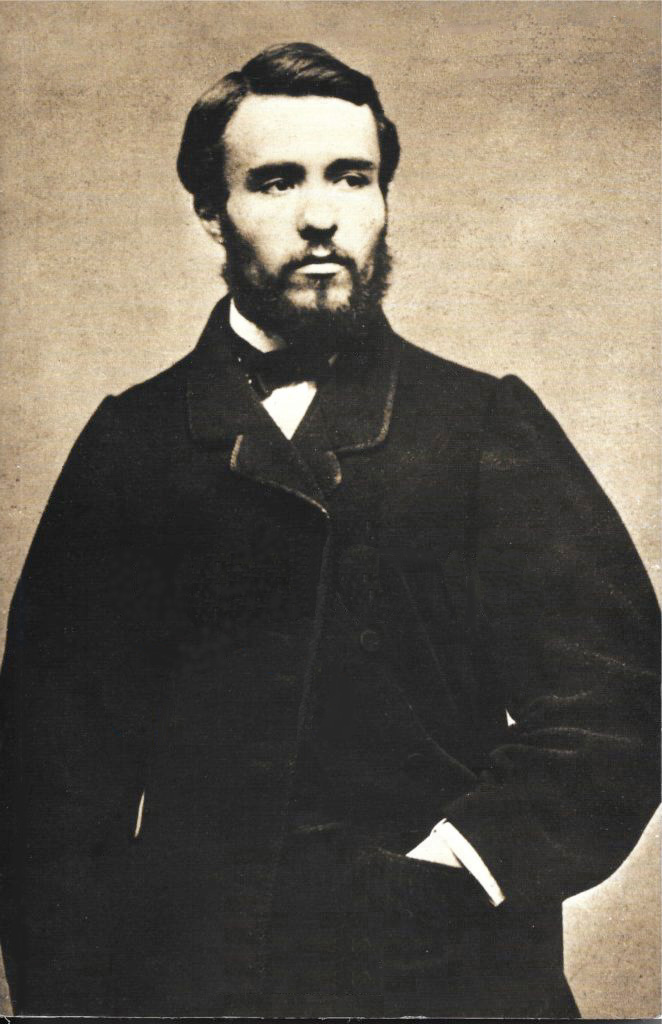

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau was born on 28 September 1841 in Mouilleron-en-Pareds, a village in the rural and historically monarchist Vendée department of northwestern France. His mother, Sophie Eucharie Gautreau (1817-1903), came from a Huguenot family. His father, Benjamin Clemenceau (1810-1897), hailed from a long line of physicians but managed his lands and investments rather than practicing medicine. Benjamin Clemenceau was a fervent political activist and a radical republican who instilled in his son a deep love of learning, a commitment to radical politics, and a strong anti-clerical stance, despite his mother being a devout Protestant. His father was an atheist and ensured his children received no religious education. Clemenceau himself remained a lifelong atheist with a notable knowledge of the Bible. His brother, Albert Clemenceau (1861-1955), later became a lawyer.

Clemenceau completed his studies at the Lycée in Nantes, earning his French baccalaureate of letters in 1858. He then moved to Paris to pursue medical studies at the University of Paris, eventually graduating with his thesis "De la génération des éléments anatomiques" in 1865.

2. American Experience

After completing his medical studies, Clemenceau became a political activist and writer in Paris, co-founding the weekly newsletter Le Travail in December 1861. His early activism led to his arrest by imperial police on 23 February 1862 for inciting a demonstration, resulting in 77 days of imprisonment in Mazas Prison. During this period, he visited other Republican activists, including Auguste Blanqui and Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, in jail, which further solidified his fervent republicanism and hatred for the Napoleon III regime.

Following a failed romantic relationship and increasing crackdowns on dissidents by imperial agents, Clemenceau left France for the United States in 1865, where he lived until 1869. He practiced medicine in New York City and contributed as a political journalist for the Parisian newspaper Le Temps. He also taught French in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and taught and rode horseback at a private girls' school in Stamford, Connecticut, where he met his future wife. During his time in America, he actively participated in French exile clubs in New York that opposed the imperial regime.

Clemenceau's journalistic work in the United States covered the country's recovery after the American Civil War, the functioning of American democracy, and issues related to the abolition of slavery. His American experience profoundly shaped his views, instilling in him a strong belief in American democratic ideals as an alternative to France's imperial system, and fostering a sense of political compromise that would later characterize his own political career.

3. Journalism and Early Political Activism

Upon his return to Paris in 1870, after the French defeat at the Battle of Sedan and the fall of the Second French Empire, Clemenceau quickly re-engaged in political journalism. He founded several literary magazines and wrote numerous articles, predominantly criticizing the imperial regime of Napoleon III.

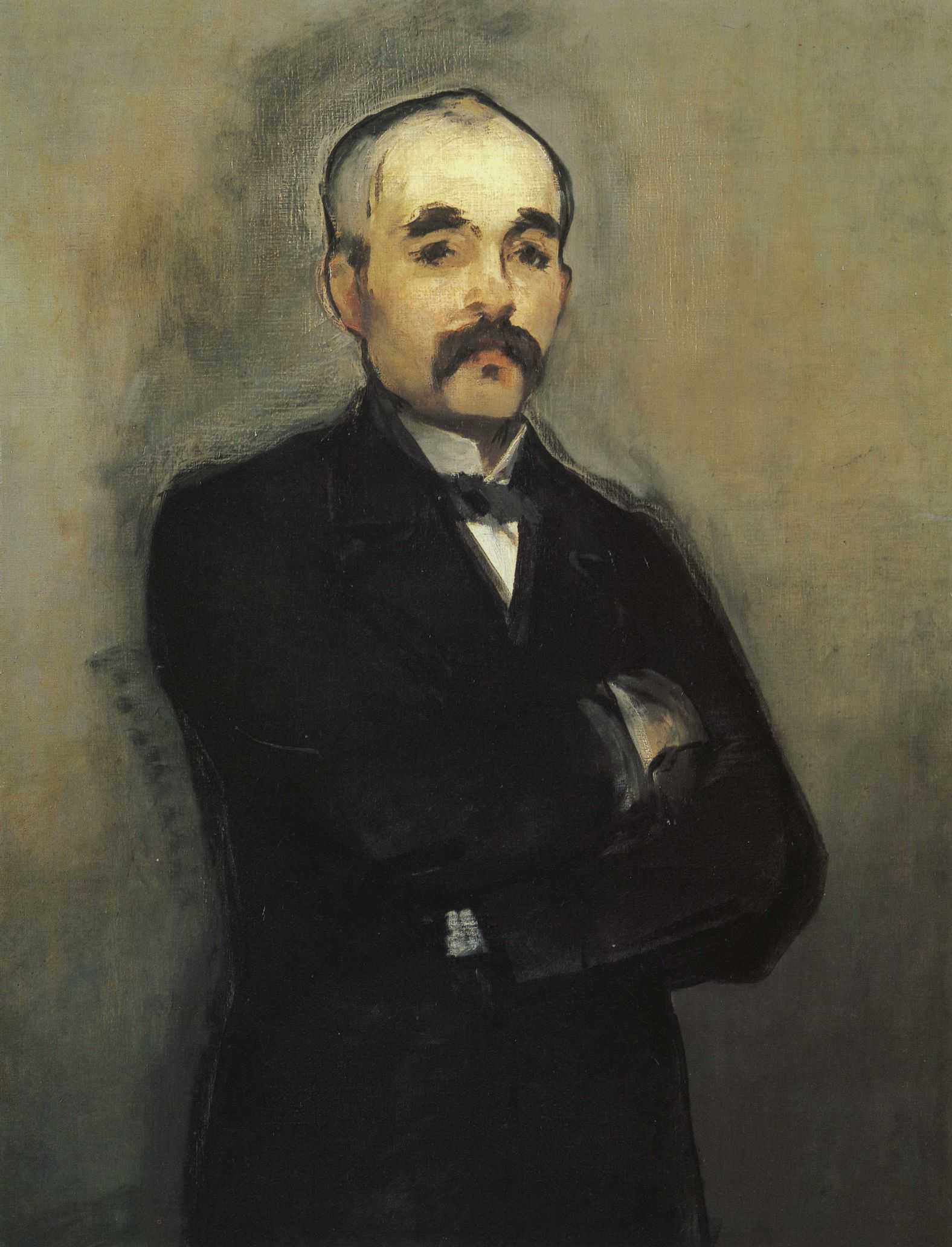

In 1880, Clemenceau established his own newspaper, La Justice (La JusticeJusticeFrench), which rapidly became the leading voice of Parisian Radicalism. Through this platform, he became widely known as a formidable political critic and a "destroyer of ministries" (le Tombeur de ministères), often bringing down governments without seeking office himself. His journalistic endeavors were central to his political influence, allowing him to shape public opinion and challenge established powers.

His most significant journalistic contribution came during the Dreyfus Affair, when he owned and edited the Paris daily newspaper L'Aurore (L'AuroreThe DawnFrench). On 13 January 1898, Clemenceau published Émile Zola's explosive open letter to the President of France, Félix Faure, under the iconic title "J'Accuse...!" (J'Accuse...!I Accuse!French). This publication was a crucial turning point in the affair, galvanizing public opinion and exposing the injustices committed against Alfred Dreyfus. Throughout the affair, Clemenceau published 665 articles defending Dreyfus and combating anti-Semitism, aligning himself with intellectuals like Zola, Anatole France, and Jean Jaurès against conservative forces including the Catholic Church and the military.

In 1900, he left La Justice to establish a weekly review, Le Bloc (Le BlocThe BlocFrench), to which he was almost the sole contributor, continuing its publication until March 1902. In June 1903, he resumed direction of L'Aurore, using it to champion the re-examination of the Dreyfus Affair and advocate for the separation of church and state in France, a goal achieved with the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State.

4. Entry into Politics

Clemenceau formally entered French political life following his return to Paris in 1870. He was appointed Mayor of the 18th arrondissement of Paris, which included Montmartre, and simultaneously elected to the National Assembly for the same arrondissement. During the Paris Commune in March 1871, he attempted to mediate a compromise between the radical Communard leaders and the more conservative French government, but his efforts were unsuccessful. The Commune declared his mayoral authority invalid and seized the 18th arrondissement city hall. He ran for election to the Paris Commune council but failed to secure a seat and did not participate in its governance. He was in Bordeaux when the Commune was brutally suppressed by the French Army in May 1871.

After the fall of the Commune, Clemenceau was elected to the Paris municipal council on 23 July 1871, representing the Clignancourt quarter. He held this seat until 1876, serving as secretary and vice-president before becoming president of the council in 1875.

5. Political Ideals and Radicalism

Clemenceau's political platform was defined by his unwavering commitment to radical republicanism. He was a staunch anti-clericalist, advocating for the strict separation of church and state in France. He believed that the state should be secular and free from religious influence, a principle he actively championed, culminating in the 1905 law on separation.

He was a vocal supporter of the general amnesty for thousands of Communards, members of the revolutionary government of 1871 who had been deported to New Caledonia. Alongside other radicals and figures like Victor Hugo, he pushed for several unsuccessful proposals until a general amnesty was finally adopted on 11 July 1880, allowing the remaining deported Communards, including his friend Louise Michel, to return to France.

Clemenceau was a fierce opponent of the colonial policy pursued by Prime Minister Jules Ferry. He opposed colonialism on both moral grounds, viewing it as a diversion from France's more critical objective: "Revenge against Germany" and the restitution of Alsace-Lorraine, which had been annexed by Germany after the Franco-Prussian War. His criticism of the Sino-French War played a significant role in the fall of Ferry's cabinet in 1885.

His strong anti-German sentiment was a defining characteristic of his political career, driven by the loss of Alsace-Lorraine. He consistently emphasized the need for France to remain vigilant and strong against potential German aggression. This deep-seated conviction would profoundly influence his policies during and after World War I.

6. The Dreyfus Affair

Clemenceau played a crucial and highly influential role as a journalist and advocate during the Dreyfus Affair, which deeply divided French society at the turn of the 20th century. Having acquired the Paris daily newspaper L'Aurore (L'AuroreThe DawnFrench), he used its front page to champion the cause of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer falsely accused of treason.

His most famous contribution was the publication of Émile Zola's open letter to President Félix Faure, titled "J'Accuse...!" (J'Accuse...!I Accuse!French), on 13 January 1898. Clemenceau himself chose the provocative title, which became an iconic symbol of the affair and a powerful indictment of the military and judicial establishment. This act of journalistic courage, defying powerful conservative and anti-Semitic forces, ignited public debate and was instrumental in turning the tide of opinion in favor of Dreyfus.

Throughout the affair, Clemenceau published an astonishing 665 articles defending Dreyfus and vigorously combating the anti-Semitic and nationalist campaigns that sought to condemn him. His unwavering support for Dreyfus and his commitment to justice and truth solidified his reputation as a defender of human rights and a champion against injustice, even at significant personal and political cost.

7. Parliamentary Career and Senate Election

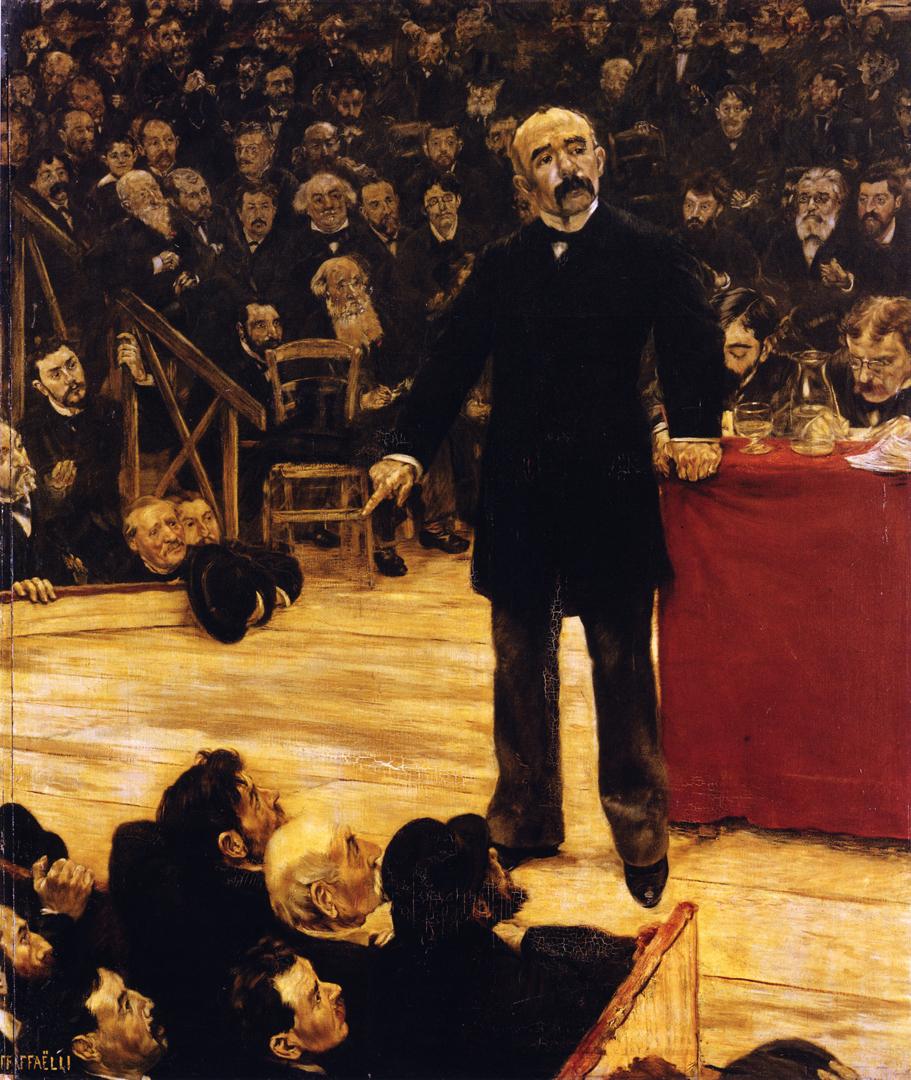

After his initial political roles, Clemenceau was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1876, representing the 18th arrondissement of Paris. He quickly rose to prominence as a leader of the radical section on the far left, known for his energy and sharp eloquence. In 1877, during the 16 May 1877 crisis, he was a leading voice among the republican majority who denounced the ministry of the Duc de Broglie, leading the resistance against anti-republican policies. His demand for the indictment of the Broglie ministry in 1879 further enhanced his reputation.

From 1876 to 1880, Clemenceau was a key advocate for the general amnesty of thousands of Communards deported to New Caledonia, successfully pushing for its adoption on 11 July 1880. He became widely known as a political critic who frequently brought down ministries, earning him the nickname le Tombeur de ministères. He was a vocal opponent of Prime Minister Jules Ferry's colonial policies, arguing they diverted attention from the more crucial goal of "Revenge against Germany" and the return of Alsace-Lorraine. His criticism of the Sino-French War significantly contributed to the fall of the Ferry cabinet in 1885.

In the 1885 French legislative election, he was elected for both his old seat in Paris and for the Var department, choosing to represent the latter. He refused to form a ministry himself but supported the inclusion of Georges Ernest Boulanger as war minister in the Charles de Freycinet cabinet in 1886. However, when Boulanger's ambitions became clear, Clemenceau withdrew his support and became a vigorous opponent of the Boulangist movement.

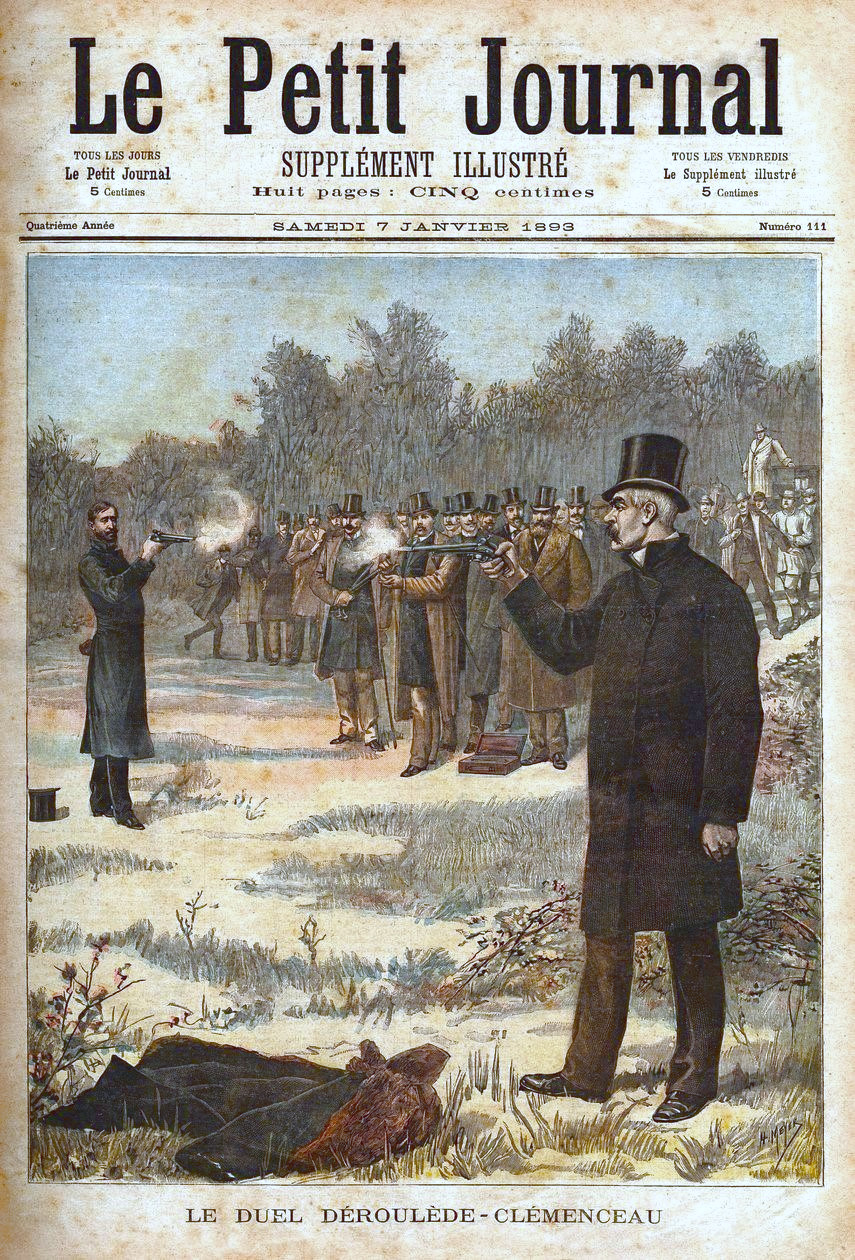

Clemenceau played a significant role in the resignation of President Jules Grévy in 1887, largely due to his exposure of the Wilson scandal. He declined Grévy's request to form a cabinet and influenced the election of Marie François Sadi Carnot as president. However, the split within the Radical Party over Boulangism weakened his position, and his association with businessman Cornelius Herz during the Panama scandals led to accusations of corruption. In response to these accusations by nationalist politician Paul Déroulède, Clemenceau famously fought a duel with him on 23 December 1892, though neither was injured.

His hostility to the Franco-Russian Alliance further diminished his popularity, leading to his defeat in the 1893 French legislative election for his Chamber of Deputies seat, which he had held continuously since 1876.

After nearly a decade focusing on journalism, Clemenceau was elected Senator for the Var department on 6 April 1902, a notable shift given his previous calls for the abolition of the French Senate, which he considered a bastion of conservatism. He served as Senator for Draguignan until 1920, gradually moderating some of his positions while still strongly supporting the Radical-Socialist ministry of Prime Minister Émile Combes, who spearheaded the anti-clerical republican struggle.

8. First Ministry (1906-1909)

In March 1906, the ministry of Maurice Rouvier collapsed amidst civil unrest stemming from the implementation of the law on the separation of church and state, coinciding with a radical victory in the 1906 French legislative election. The new government, led by Ferdinand Sarrien, appointed Clemenceau as Minister of the Interior. In this role, Clemenceau initiated significant reforms of the French police forces, supporting the development of scientific policing by Alphonse Bertillon and establishing the Brigades mobiles (French for "mobile squads") under Célestin Hennion. These squads earned the nickname Brigades du Tigre ("The Tiger's Brigades"), a direct reference to Clemenceau's own moniker, "The Tiger."

Domestically, Clemenceau adopted a firm, often repressive, stance towards labor movements. He ordered the military to suppress miners' strikes in the Pas-de-Calais following the devastating Courrières mine disaster in 1906, which claimed over a thousand lives. He also repressed the wine growers' strike in the Languedoc-Roussillon region in 1907. These actions alienated the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) socialist party, leading to a definitive break with their leader, Jean Jaurès, in a notable debate in the Chamber of Deputies in June 1906. Clemenceau's strong leadership during these crises positioned him as a dominant figure in French politics. When the Sarrien ministry resigned in October 1906, Clemenceau was appointed Premier, a position he held until 1909.

As Prime Minister, he continued to oversee internal affairs as Minister of the Interior. In foreign policy, he focused on strengthening ties with Britain, leading to the development of a new Entente cordiale during 1907 and 1908, which enhanced France's role in European politics. Difficulties with Germany, particularly concerning the First Moroccan Crisis (1905-06), were resolved at the Algeciras Conference.

Clemenceau's first ministry faced challenges, and he was ultimately defeated on 20 July 1909 during a debate in the Chamber of Deputies concerning the state of the navy. Following a bitter exchange with Théophile Delcassé, whose political downfall Clemenceau had previously assisted, his proposal for the order of the day vote was rejected. Refusing to respond to Delcassé's technical questions, Clemenceau resigned. He was succeeded as premier by Aristide Briand, who formed a reconstructed cabinet.

9. World War I and Second Ministry (1917-1920)

Between his two premierships, Clemenceau dedicated his time to travel, conferences, and writing. In 1910, he traveled to South America, visiting Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, where he was impressed by the influence of French culture and the French Revolution on local elites. He founded the newspaper L'Homme libre ("The Free Man") in Paris on 6 May 1913, through which he wrote daily editorials increasingly focused on foreign policy and condemning the anti-militarism of the Socialists.

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Clemenceau's newspaper was among the first to be censored by the government. It was suspended from 29 September to 7 October. In response, Clemenceau defiantly renamed it L'Homme enchaîné ("The Chained Man") and continued to criticize the government for its lack of transparency and effectiveness, while simultaneously defending the patriotic union sacrée (sacred union) against the German Empire.

Despite the censorship, Clemenceau retained significant political influence. He advised Interior Minister Louis Malvy to invoke Carnet B, a list of suspected subversives, to prevent a collapse of public support for the war effort, though the government did not fully follow this advice. In autumn 1914, he declined to join the government of national unity as justice minister.

He became a vehement critic of the wartime French government, arguing it was not doing enough to win the war, driven by his strong desire to regain Alsace-Lorraine. The dire situation in autumn 1917, marked by the Italian defeat at the Battle of Caporetto, the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia, and rumors of treason involving former Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux and Interior Minister Louis Malvy, led Prime Minister Paul Painlevé to consider negotiations with Germany. Clemenceau adamantly opposed this, insisting that even the return of Alsace-Lorraine and the liberation of Belgium would not justify France abandoning its allies. His prominent opposition ensured that there would be no separate peace, and German documents later confirmed that Germany had no serious intention of returning Alsace-Lorraine anyway. His newspaper endlessly published the phrase: "Messieurs, les Allemands sont toujours à Noyon" (Gentlemen, the Germans are still at Noyon), highlighting the continued German occupation of French territory.

In November 1917, during one of the darkest periods for the French war effort, Clemenceau was appointed Prime Minister. Unlike his predecessors, he discouraged internal disagreement among senior politicians and called for national unity. His first act was to relieve General Maurice Sarrail from his command of the Salonika front due to Sarrail's links with suspected socialist politicians. Winston Churchill later described Clemenceau in this role as resembling "a wild animal pacing to and fro behind bars" before an assembly that felt compelled to obey him.

When Clemenceau took power, victory seemed distant. The western front was largely static, Italy was on the defensive, and Russia was effectively out of the war. Domestically, France faced increasing anti-war demonstrations, resource scarcity, and air raids on Paris that damaged morale. Clemenceau, despite his years of criticizing others, found himself in a position of supreme power but politically isolated, relying on his own circle of friends. He appointed General Henri Mordacq as his military chief of staff, who helped foster trust and mutual respect between the army and the government, crucial for the eventual victory.

Initially, the men in the trenches saw Clemenceau as "just another politician," but his frequent visits to the front lines gradually inspired confidence among the fighting men, which then spread to the home front. He was widely seen as a strong leader who never lost faith in France's ability to achieve total victory.

9.1. 1918: Crackdown and Total War

As the military situation worsened in early 1918, Clemenceau remained committed to a policy of "total war" and "la guerre jusqu'au bout" (war until the end). His speech on 8 March advocating this policy left a profound impression on Winston Churchill. Clemenceau's war policy encompassed the promise of victory with justice, loyalty to the fighting forces, and immediate and severe punishment for crimes against France.

He viewed former Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux, who advocated for negotiating peace with Germany, as a threat to national security. Unlike previous ministers, Clemenceau publicly moved against Caillaux, leading to his arrest and imprisonment for three years. Clemenceau argued that Caillaux's "crime was not to have believed in victory [and] to have gambled on his nation's defeat." While these arrests raised concerns about Clemenceau's harshness, he maintained that he only assumed powers necessary for winning the war. Far from instilling fear, these trials inspired public confidence, as people felt that decisive action was finally being taken. Clemenceau also relaxed censorship on political views, believing that newspapers had the right to criticize government figures.

In 1918, Clemenceau supported Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, particularly the call for the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, which aligned with a crucial French war aim. However, he remained skeptical about other points, such as the League of Nations, which he believed could only succeed in a utopian society.

9.2. 1918: German Spring Offensive and Allied Victory

On 21 March 1918, Germany launched its major German spring offensive, catching the Allies off guard and creating a dangerous gap in the British and French lines that threatened Paris. This defeat solidified Clemenceau's conviction, shared by other Allied leaders, that a coordinated, unified command was essential. Consequently, Ferdinand Foch was appointed "generalissimo" of the Allied forces.

As the German advance continued, Clemenceau acknowledged the possibility of Paris falling. Despite public sentiment suggesting that a change in government might lead to a more advantageous peace with Germany, Clemenceau adamantly opposed such notions. He delivered an inspiring speech in the Chamber of Deputies, securing a vote of confidence by 377 votes to 110.

As the Allied counter-offensives pushed the Germans back, it became clear that Germany could no longer win the war. With its allies seeking armistices, Germany soon followed suit. On 11 November 1918, the armistice with Germany was signed, marking the end of the war. Clemenceau was widely celebrated in the streets of Paris, attracting admiring crowds as "Father Victory."

10. Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles

To address the complex international political issues following World War I, the Paris Peace Conference was convened in Paris in 1919. The resulting Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended the conflict with Germany, was signed in the Palace of Versailles, but the crucial deliberations took place in Paris. On 13 December 1918, United States President Woodrow Wilson received an enthusiastic welcome in France, where his Fourteen Points and the concept of a League of Nations resonated deeply with the war-weary French populace. Clemenceau, upon meeting Wilson, recognized him as a man of principle.

Given that the conference was held in France, Clemenceau was deemed the most suitable president, also being fluent in both English and French, the official languages of the conference. He held an unassailable position, maintaining full control of the French delegation. Parliament granted him a vote of confidence on 30 December 1918, with a vote of 398 to 93. France was allotted five plenipotentiaries, with Clemenceau and four others who largely served as his instruments. He deliberately excluded all military figures, especially Ferdinand Foch, and kept President Raymond Poincaré in the dark about negotiation progress. He also excluded parliamentary deputies, asserting that he would negotiate the treaty, and it would be Parliament's duty to either approve or reject it once completed.

The conference's progress was slower than anticipated, leading Clemenceau to express his irritation in an interview with an American journalist. He voiced concerns that Germany had won the war industrially and commercially, with its factories intact, and would soon overcome its debts through "manipulation," potentially making its economy stronger than France's in a short time. Clemenceau's leverage was often jeopardized by his mistrust of Wilson and David Lloyd George, and his intense dislike of President Poincaré. When negotiations stalled, he would sometimes shout at other heads of state and leave the room rather than continue discussions.

10.1. Attempted Assassination

On 19 February 1919, as Clemenceau was leaving his apartment, an anarchist named Émile Cottin fired several shots at his car. Cottin was almost lynched by the crowd. Clemenceau's assistant found him pale but conscious. Clemenceau famously remarked, "They shot me in the back. They didn't even dare to attack me from the front." One bullet struck him between the ribs, narrowly missing vital organs, and remained in his body for the rest of his life as it was too dangerous to remove.

Clemenceau often joked about his assailant's poor marksmanship: "We have just won the most terrible war in history, yet here is a Frenchman who misses his target six out of seven times at point-blank range. Of course this fellow must be punished for the careless use of a dangerous weapon and for poor marksmanship. I suggest that he be locked up for eight years, with intensive training in a shooting gallery."

10.2. Rhineland and the Saar

Upon Clemenceau's return to the Council of Ten on 1 March, the dispute over France's eastern frontier and control of the German Rhineland remained unresolved. Clemenceau believed that Germany's possession of this territory left France vulnerable to invasion, lacking a natural eastern border. In December 1918, the British ambassador reported Clemenceau's view that the Rhine should become the German boundary, with the territory between the Rhine and the French frontier forming an independent, neutral state guaranteed by the great powers.

The issue was eventually resolved when Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson guaranteed immediate military assistance if Germany launched an unprovoked attack. It was also decided that the Allies would occupy the Rhineland for fifteen years, and Germany would be permanently forbidden from rearming the area. Lloyd George insisted on a clause allowing early withdrawal of Allied troops if Germany fulfilled the treaty terms. Clemenceau, however, inserted Article 429 into the treaty, permitting Allied occupation beyond fifteen years if adequate guarantees for Allied security against unprovoked aggression were not met. This provision was crucial in case the U.S. Senate failed to ratify the Treaty of Guarantee, which would also nullify the British guarantee. This indeed occurred, and Article 429 ensured the security provisions remained robust.

President Poincaré and Marshal Foch consistently pressed for an autonomous Rhineland state, with Foch famously stating that the Treaty of Versailles was "not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years," believing it was too lenient on Germany. Clemenceau, however, prioritized the alliance with America and Britain over an isolated France holding onto the Rhineland. He told Lloyd George in June that France needed "a barrier behind which, in the years to come, our people can work in security to rebuild its ruins. The barrier is the Rhine." He also stated that Foch and Poincaré's policy was "bad in principle" and that France should not emulate Bismarck's territorial ambitions.

Growing discontent over slow progress and information leaks led Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Woodrow Wilson to form the smaller Council of Four, with Vittorio Orlando of Italy as the fourth member, to enhance privacy and efficiency. Another major issue discussed was the future of the German Saar region. Clemenceau argued that France was entitled to the region and its coal mines due to Germany's deliberate damage to northern French coal mines. Wilson strongly resisted this claim, leading Clemenceau to accuse him of being "pro-German." Lloyd George brokered a compromise: the coal mines were ceded to France, and the territory was placed under French administration for 15 years, after which a plebiscite would determine its future status.

Although Clemenceau had limited knowledge of the defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire, he supported the causes of its smaller ethnic groups. His firm stance contributed to the stringent terms of the Treaty of Trianon, which dismantled Hungary. Rather than solely adhering to the principle of self-determination, Clemenceau sought to weaken Hungary, mirroring the treatment of Germany, to eliminate the threat of a large power in Central Europe. The creation of a unified Czechoslovakian state, encompassing majority Hungarian territories, was also seen as a potential buffer against Communism.

10.3. Reparations

Clemenceau lacked expertise in economics and finance, and as John Maynard Keynes observed, he "did not trouble his head to understand either the Indemnity or [France's] overwhelming financial difficulties." However, he faced immense public and parliamentary pressure to impose the largest possible reparations bill on Germany. While there was general agreement that Germany should not pay more than it could afford, estimates varied widely, from 2.00 B GBP to 20.00 B GBP. Clemenceau realized that any direct compromise on a figure would anger both French and British citizens. Therefore, the only viable option was to establish a reparations commission that would assess Germany's capacity to pay, effectively removing the French government from direct involvement in setting the reparations amount.

10.4. Defense of the Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. Clemenceau then faced the formidable task of defending the treaty against critics who argued that the compromises he had negotiated were insufficient for French national interests. During the French Parliament's debate on the treaty, Louis Barthou claimed on 24 September that the U.S. Senate would not ratify either the Treaty of Guarantee or the Treaty of Versailles, suggesting it would have been wiser to secure the Rhine as a permanent frontier. Clemenceau countered that he was confident the Senate would ratify both treaties and that he had inserted Article 429, providing for "new arrangements concerning the Rhine," to ensure France's security regardless of the U.S. decision. Barthou, however, disputed this interpretation of Article 429.

Clemenceau delivered his main speech defending the treaty on 25 September. He acknowledged that the treaty was not perfect, but emphasized that it was the product of a coalition war and thus represented the lowest common denominator among the Allies. He dismissed criticisms of specific details as misleading, urging critics to view the treaty holistically and consider its overall benefits. He famously stated:

"The treaty, with all its complex clauses, will only be worth what you are worth; it will be what you make it... What you are going to vote to-day is not even a beginning, it is a beginning of a beginning. The ideas it contains will grow and bear fruit. You have won the power to impose them on a defeated Germany. We are told that she will revive. All the more reason not to show her that we fear her... Life is a perpetual struggle in war, as in peace... That struggle cannot be avoided. Yes, we must have vigilance, we must have a great deal of vigilance. I cannot say for how many years, perhaps I should say for how many centuries, the crisis which has begun will continue. Yes, this treaty will bring us burdens, troubles, miseries, difficulties, and that will continue for long years."

The Chamber of Deputies ratified the treaty by 372 votes to 53, and the Senate voted unanimously for its ratification. On 11 October, Clemenceau delivered his final parliamentary speech to the Senate. He argued that any attempt to partition Germany would be self-defeating and that France must find a way to coexist with sixty million Germans. He also asserted that the bourgeoisie, like the aristocracy before them, had failed as a ruling class, and it was now the working class's turn to govern. He advocated for national unity and a demographic revolution, stating: "The treaty does not state that France will have many children, but it is the first thing that should have been written there. For if France does not have large families, it will be in vain that you put all the finest clauses in the treaty, that you take away all the Germans guns, France will be lost because there will be no more French."

11. Post-War Domestic Policies and Reforms

Clemenceau's second premiership, following World War I, saw the implementation of significant domestic reforms aimed at improving workers' conditions and regulating labor hours.

Most notably, a general eight-hour day law was passed in April 1919, amending the French Labour Code. In June of the same year, existing legislation concerning working hours in the mining industry was extended, applying the eight-hour day to all classes of workers, whether employed underground or on the surface. Previously, a December 1913 law had limited the eight-hour day only to underground workers. In August 1919, a similar limit was introduced for all those employed on French vessels.

Another notable law passed in 1919 (which came into operation in October 1920) prohibited employment in bakeries between the hours of 10 P.M. and 4 A.M. This law is sometimes credited with contributing to the popularization, if not the development, of the baguette as a dominant form of bread in France, with the earliest written references to a "baguette" as a style of bread dating from August 1920. A decree in May 1919 introduced the eight-hour day for workers on trams, railways, and in inland waterways, and a second decree in June 1919 extended this provision to the state railways. In April 1919, an enabling act was approved for an eight-hour day and a six-day work week, though farm workers were excluded from this act.

12. Assassination Attempt and Presidential Bid

In 1919, France adopted a new electoral system, and the 1919 French legislative election resulted in a majority for the National Bloc, a coalition of right-wing parties. Clemenceau intervened only once in the election campaign, delivering a speech in Strasbourg on 4 November, where he praised the National Bloc's manifesto and urged that the victory in the war be safeguarded by vigilance. Privately, he was concerned by this significant shift to the right.

His friend, Georges Mandel, encouraged Clemenceau to run for the presidency in the upcoming election. On 15 January 1920, Clemenceau allowed Mandel to announce his willingness to serve if elected. However, Clemenceau did not intend to campaign for the position; instead, he desired to be chosen by acclamation as a national symbol. The preliminary meeting of the republican caucus, a precursor to the vote in the National Assembly, ultimately chose Paul Deschanel over Clemenceau by a vote of 408 to 389. In response, Clemenceau refused to be put forward for the vote in the National Assembly, stating that he did not wish to win by a small majority but rather by a near-unanimous vote, which he believed was necessary to negotiate confidently with the allies.

In his final speech to the cabinet on 18 January, Clemenceau expressed his concerns: "We must show the world the extent of our victory, and we must take up the mentality and habits of a victorious people, which once more takes its place at the head of Europe. But all that will now be placed in jeopardy... It will take less time and less thought to destroy the edifice so patiently and painfully erected than it took to complete it. Poor France. The mistakes have begun already." Following his unsuccessful presidential bid, Clemenceau resigned as prime minister on 17 January 1920, effectively retiring from active politics.

13. Later Life and Literary Pursuits

After his resignation as prime minister and withdrawal from politics in January 1920, Clemenceau embarked on a period of extensive travel and literary endeavors. He took a holiday in Egypt and the Sudan from February to April 1920, followed by a journey to the Far East in September, returning to France in March 1921. In June 1921, he visited England and received an honorary degree from the University of Oxford. During this visit, he met David Lloyd George, humorously remarking that after the armistice, Lloyd George had become an enemy of France. Lloyd George, in jest, replied, "Well, was not that always our traditional policy?" Clemenceau, upon reflection, took this seriously. After Lloyd George's fall from power in 1922, Clemenceau commented, "As for France, it is a real enemy who disappears. Lloyd George did not hide it: at my last visit to London he cynically admitted it."

In late 1922, Clemenceau undertook a lecture tour in major cities of the American Northeast. He passionately defended France's policies, including war debts and reparations, and condemned American isolationism. He was well-received and attracted large audiences, though America's policy remained unchanged. On 9 August 1926, he wrote an open letter to American President Calvin Coolidge, arguing against France paying all its war debts with the declaration: "France is not for sale, even to her friends." This appeal, however, went unheeded. He also criticized Raymond Poincaré's occupation of the Ruhr in 1923, viewing it as an undoing of the entente between France and Britain.

Clemenceau dedicated much of his later life to writing. He penned two short biographies, one on the Greek orator Demosthenes and another on his close friend, the French painter Claude Monet. Between 1923 and 1927, he spent most of his time writing a massive two-volume work covering philosophy, history, and science, titled Au Soir de la Pensée (At the Evening of Thought).

In his final months, despite earlier declarations that he would not write them, Clemenceau began composing his memoirs. He was spurred to do so by the publication of Marshal Foch's memoirs, which were highly critical of Clemenceau's policies at the Paris Peace Conference. Clemenceau only managed to finish the first draft, which was published posthumously as Grandeurs et miseres d'une victoire (Grandeur and Misery of Victory). In this work, he criticized Foch and his successors for allowing the Treaty of Versailles to be undermined in the face of Germany's resurgence. Before his death, he burned all his private letters.

Georges Clemenceau died on 24 November 1929 in Paris and was buried in a simple grave next to his father's at Mouchamps, in his native Vendée.

14. Personal Life and Beliefs

On 23 June 1869, Georges Clemenceau married Mary Eliza Plummer (1849-1922) in New York City. She had been one of his students at the school where he taught horseback riding, and was the daughter of Harriet A. Taylor and William Kelly Plummer. Following their marriage, the Clemenceaus moved to France and had three children: Madeleine (born 1870), Thérèse (1872), and Michel (1873). Despite Clemenceau's own numerous extramarital affairs, when his wife took a tutor of their children as her lover, Clemenceau had her imprisoned for two weeks before sending her back to the United States in third class on a steamer. Their marriage ended in a contentious divorce in 1891, with Clemenceau gaining custody of their children and subsequently having his wife stripped of her French nationality.

Clemenceau was a lifelong atheist and a prominent leader of anti-clerical or "Radical" forces that opposed the Catholic Church in France and its political influence. While he zealously opposed the idea of God and advocated for revolt against it, he generally stopped short of more extreme attacks, maintaining that if church and state were rigidly separated, he would not support oppressive measures designed to further weaken the Catholic Church.

He was a long-time friend and ardent supporter of the Impressionist painter Claude Monet. Clemenceau was instrumental in persuading Monet to undergo a cataract operation in 1923. For over a decade, Clemenceau encouraged Monet to complete his donation to the French state of the large Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies) paintings, which are now displayed in specially constructed oval galleries at the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, opened to the public in 1927. The Japanese source notes that Monet's famous Water Lilies series was painted at Clemenceau's suggestion.

Clemenceau was known for his physical discipline and practiced fencing every morning, even in old age, having engaged in a dozen duels against political opponents throughout his life. He also developed a keen interest in Japanese art, particularly Japanese ceramics. He amassed a collection of approximately 3,000 small incense containers (kōgō 香合kōgōJapanese), many of which are now housed in museums. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts held a special exhibition of his collection in 1978.

An anecdote from the Japanese source recounts Clemenceau's strong opinions on ethnicity and geography, where he publicly stated that "Italians are half-dirty blood" because parts of Southern Italy were historically ruled by Arabs and Muslims, implying "dirty blood" meant "non-European blood," referring to Arabs and the darker complexion of Southern Italians.

He also maintained friendships with Japanese figures, including Saionji Kinmochi, a Japanese plenipotentiary at the Paris Peace Conference, whom he knew from their shared boarding house days in Paris. Another anecdote mentions his friendship with Prince Higashikuni Naruhiko, whom he met through Monet. Clemenceau reportedly warned Prince Higashikuni that "America is preparing to strike Japan" (referencing the Orange Plan), leading the Prince to advocate against a Japan-U.S. war upon his return to Japan, though his efforts were largely unheeded by Japanese military leaders like Hideki Tojo.

15. Legacy and Historical Assessment

Georges Clemenceau's historical significance is profound, marked by his transformative leadership during World War I and his lasting influence on French politics and national identity. He is widely remembered as "Father Victory" and "The Tiger" for his unwavering resolve and determination to achieve total victory against Germany. His return to power in 1917, at a moment of deep crisis for France, is often credited with revitalizing the nation's war effort and morale.

His role at the Paris Peace Conference and in shaping the Treaty of Versailles remains a subject of considerable debate. Clemenceau's insistence on harsh terms for Germany, including extensive reparations and territorial concessions, reflected a deep-seated French desire for security and retribution after two devastating invasions. While some critics, like Marshal Foch, believed the treaty was too lenient and would lead to future conflict, others argued that Clemenceau's demands contributed to German resentment and instability in the interwar period. His commitment to French security, however, was paramount, as evidenced by his efforts to secure guarantees and maintain a strong stance on the Rhineland.

Domestically, Clemenceau was a committed radical republican who championed the separation of church and state and supported the amnesty of Communards. His first ministry saw significant police reforms and the suppression of labor movements, which alienated socialists but solidified his image as a strong leader. In his second ministry, he oversaw important social reforms, notably the implementation of the eight-hour day and other labor regulations, demonstrating a commitment to improving workers' conditions.

Clemenceau's political career was characterized by his fierce independence, his powerful oratory, and his willingness to challenge established figures and policies. He was a formidable journalist who used his newspapers to expose corruption and champion causes like the Dreyfus Affair, defending justice and human rights against anti-Semitism and military injustice.

Despite his authoritarian tendencies during wartime, Clemenceau remained accountable to the public and the media, even relaxing censorship on political views. His unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1920 marked his final departure from active politics, but his legacy as a statesman who guided France through its most challenging period in modern history ensues. His posthumously published memoirs, Grandeur and Misery of Victory, reflect his continued concern for France's future and his critical assessment of those who, in his view, undermined the Versailles Treaty.

16. Memorials and Namesakes

Numerous places, institutions, and objects have been named in honor of Georges Clemenceau, reflecting his lasting impact and recognition in France and beyond.

- The Musée Clemenceau in Paris, his former apartment, was purchased for him by his friend James Douglas, Jr. in 1926 to serve as his retirement home and later became a museum dedicated to his life and work.

- Clemenceau, Arizona, U.S., was named in his honor by James Douglas, Jr. in 1917.

- Mount Clemenceau (12 K ft (3.66 K m)) in the Canadian Rockies was named after him in 1919.

- A Richelieu-class battleship, laid down in January 1939 and destroyed by Allied bombing in 1944, was intended to be named after Clemenceau.

- The French aircraft carrier Clemenceau (R98) was named in his honor.

- Champs-Élysées - Clemenceau is a station on lines 1 and 13 of the Paris Métro, located in the 8th arrondissement beneath Avenue des Champs-Élysées and Place Clemenceau.

- The Cuban Romeo y Julieta cigar brand once produced a size named the Clemenceau, and the Dominican-made variety still does.

- A street in Beirut, Lebanon, is named Rue Clemenceau.

- A street in Verdun, a southeastern suburb of Montreal, Canada, is named Clemenceau.

- Clemenceau Avenue in Singapore was named in his honor after his visit in the 1920s, during which he laid the foundation stone of a cenotaph. The Clemenceau Bridge (1920s) also crossed the Singapore River.

- A street in the center of Belgrade, Serbia, is named after him.

- A street in the center of Bucharest, Romania, is named after him.

- A street in the center of Antibes, France, is named after him.

17. Portrayals in Media

Georges Clemenceau has been depicted in various films and television series:

- Leonard Shephard in Dreyfus (1931)

- Grant Mitchell in The Life of Emile Zola (1937)

- Alberto Morin in Tennessee Johnson (1942)

- Marcel Dalio in Wilson (1944)

- Gnat Yura in The Unforgettable Year 1919 (1951)

- Peter Illing in I Accuse! (1958)

- John Bennett in Fall of Eagles (1974)

- Michael Anthony in The Life and Times of David Lloyd George (1981)

- Arnold Diamond in A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia (1992)

- Cyril Cusack as "George Clemenceau" in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles episode Paris, May 1919 (1993)

- Brian Cox in The Nature Vacations of Fantastic World of the Adventure (2016)

- Gérard Chaillou in An Officer and a Spy (2019)

- André Dussolier in The Tiger and the President (2022)

Clemenceau's famous line, "War is too important to be left to the generals," is quoted by the character Gen. Jack Ripper in Stanley Kubrick's 1964 film Dr. Strangelove. It is also quoted in the 1994 Exosquad episode "Mind Set," though misattributed to Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord.

18. See Also

- Interwar France

- International relations (1919-1939)