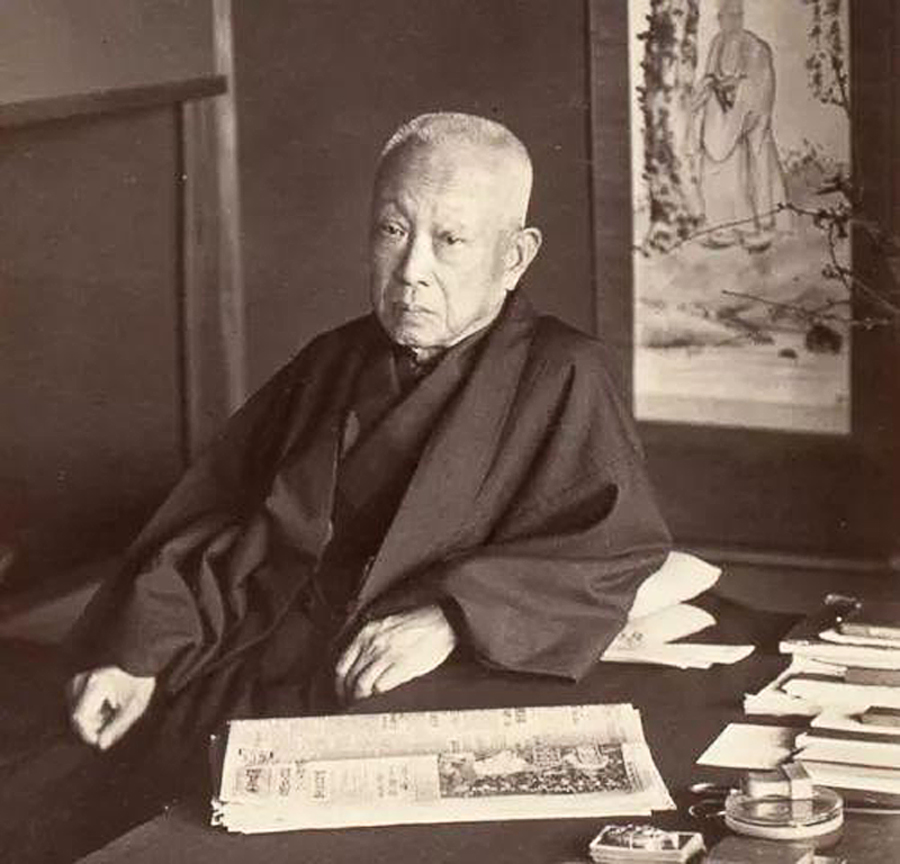

1. Early life and background

Saionji Kinmochi's early life was marked by his noble birth, his adoption into the Saionji family, and a comprehensive education that included extensive overseas studies in France. These formative experiences profoundly shaped his liberal political views and prepared him for a distinguished career in public service.

1.1. Birth and family background

Saionji Kinmochi was born on December 7, 1849, in Kyoto, Yamashiro Province (present-day Kyoto Prefecture), as the second son of Tokudaiji Kin'ito (1821-1883), head of the Tokudaiji family, a prominent kuge (court nobility) family of the Seika-ke lineage. His biological mother was Fujiko Suehiro. At the age of two, he was adopted by the Saionji family, another Seika-ke lineage, inheriting the family headship after his adoptive father, Saionji Morosue, died in July of the same year. Despite the adoption, Kinmochi grew up in close proximity to his biological parents, as both the Tokudaiji and Saionji residences were near the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

From a young age, Saionji was frequently invited to the palace as a playmate for Prince Sachinomiya, who would later become Emperor Meiji. They developed a close friendship over time. His biological elder brother, Tokudaiji Sanetsune, later became the Grand Chamberlain of Japan three times and served as Minister of the Imperial Household. Another younger brother, Sumitomo Tomoito, was adopted into the wealthy Sumitomo zaibatsu family, becoming the 15th head of the Sumitomo clan as Sumitomo Kichizaemon. Sumitomo's wealth substantially financed Saionji's political career. Saionji's close ties to the Imperial Court provided him with significant advantages and access throughout his life.

1.2. Education and overseas studies

Saionji's formal education began at Gakushūin (Peers' School), established by Emperor Kōmei. From the age of 11, he served in the Imperial Palace as a chamberlain. During this period, he also became close to Iwakura Tomomi, a fellow chamberlain. He studied classical Chinese literature under mentors like Itō Yūsai and Akita Shūsetsu, and also trained in swordsmanship under Toda Isshinsai and Fushimi Shūji. He developed an early interest in global affairs by reading books like Seiyō Jijō (Conditions in the West) by Fukuzawa Yukichi. Despite his noble background, he recalled disliking the traditional court rituals and the family's traditional practice of playing the biwa, preferring to focus on the political changes of his era.

After the Meiji Restoration, Saionji resigned from his post and, with the support of Ōmura Masujirō, began studying French in Tokyo. In December 1870, at the age of 21, he left Japan on a government scholarship for France. En route, he visited the United States, where he met President Ulysses S. Grant. He arrived in Paris on May 27, 1871, during the tumultuous period of the Paris Commune. Though initially holding reactionary views, his time in France, particularly his studies at the University of Paris under political scientist Émile Acollas, profoundly influenced his liberal political thought. He became the first Japanese student to earn a bachelor's degree from the Sorbonne. He also established close ties with prominent figures like Georges Clemenceau (later Prime Minister of France), Léon Gambetta, and fellow Japanese students such as Nakae Chōmin, Matsuda Masahisa, and Kishimoto Tatsuo. This network of connections proved beneficial later in his career. While in Paris, he also assisted Judith Gautier with the French translation of Japanese waka poetry. Though he received a generous government scholarship, he later requested a reduction in funds and eventually transitioned to being a private student to ease the financial burden on his family, receiving support from Emperor Meiji's personal funds.

1.3. Early political activities

Saionji participated in the Boshin War (1867-1868), which led to the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule. Initially, some court nobles viewed the conflict as a private dispute between samurai clans, but Saionji strongly argued that the Imperial Court should take an active role. He served as an imperial representative in various battles, including the bloodless captures of Kameoka Castle, Sasayama Castle, and Fukuchiyama. He carried an Imperial banner, which often led to the surrender of Tokugawa forces without a fight. He was later appointed governor of Echigo Province.

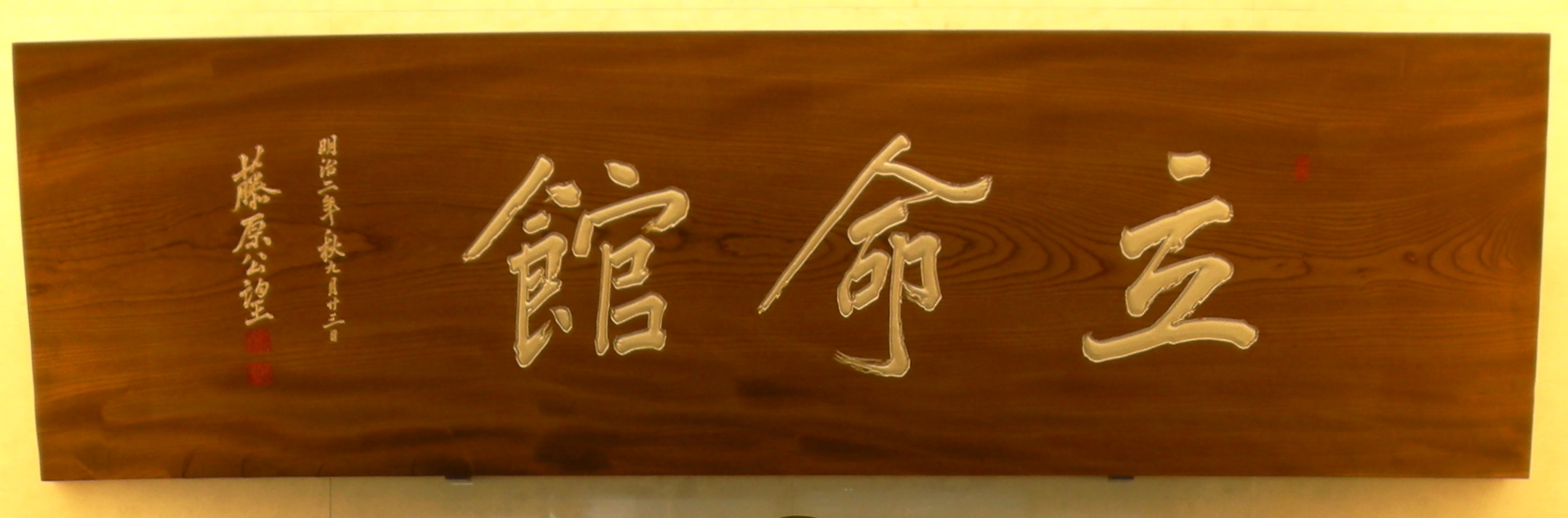

After returning to Japan, Saionji founded the private school "Ritsumeikan" in Kyoto in September 1869, which aimed to provide a more modern education, though it was closed by the Kyoto Prefectural Office after about a year due to its discussion of current events. In 1881, he, along with Nakae Chōmin and Matsuda Masahisa, launched the newspaper Tōyō Jiyū Shinbun (Oriental Free Newspaper). However, the government, displeased with his involvement in the Freedom and People's Rights Movement, pressured him to resign as president through an imperial decree. The newspaper ceased publication shortly thereafter. In November 1881, he formally re-entered government service as an assistant councilor in the Council of State.

2. Political career before premiership

Prior to assuming the role of Prime Minister, Saionji Kinmochi served in various significant governmental and party positions, demonstrating his growing influence as a statesman and his commitment to liberal and parliamentary ideals.

2.1. Service under Itō Hirobumi

Saionji's political career began to solidify through his close association with Itō Hirobumi. In 1882, Itō invited Saionji to accompany him on a tour of Europe to research constitutional systems, during which Saionji's legal and political expertise proved invaluable. Upon their return, Saionji was appointed as a minister to Austria-Hungary in 1885, and subsequently to Germany and Belgium in 1887. During his time abroad, he maintained constant communication with Itō, offering policy advice. He also befriended Mutsu Munemitsu, strengthening his position as a confidant of Itō.

After returning to Japan in 1891, he held various key posts, including President of the Bureau of Decorations. He served as Vice President of the House of Peers in the Imperial Diet. Saionji was appointed Minister of Education in the second (1894-1896) and third (1898) cabinets led by Itō, as well as in the second Matsukata Masayoshi administration. During his tenure as Minister of Education, he championed reforms to improve the quality of the educational curriculum, aiming to align it with international (Western) standards. He emphasized the importance of science, foreign language learning, and women's education. He also temporarily served as Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1895 and officially in 1896, dealing with critical issues such as those concerning the Korean Peninsula.

2.2. Rikken Seiyūkai presidency

In 1900, Itō Hirobumi founded the Rikken Seiyūkai (Constitutional Association of Political Friends), and Saionji became one of its founding members and a key executive. His European experience had instilled in him a liberal political viewpoint, and he became one of the few early politicians who firmly believed that the majority party in parliament should form the basis of the cabinet.

In October 1900, when the Fourth Itō Cabinet was formed, Saionji served as an **acting Prime Minister** due to Itō's illness, demonstrating his trusted position. On July 14, 1903, he succeeded Itō Hirobumi as the second president of the Rikken Seiyūkai. Despite some initial instability within the party due to Itō's resignation, Saionji managed to maintain its position as the leading party. However, the actual management of party affairs was largely handled by figures like Hara Takashi, who would later become a significant political figure himself.

3. Prime ministerships

Saionji Kinmochi served two terms as Prime Minister, a period known as the "Keien era" for the alternating premierships between himself and Katsura Tarō. During these tenures, he navigated complex national issues, including budget constraints, international relations, and significant conflicts with the increasingly influential military.

3.1. First and second cabinets

Saionji's first term as Prime Minister was from January 7, 1906, to July 14, 1908, and his second term was from August 30, 1911, to December 21, 1912. These periods saw a continuous power struggle between Saionji, who supported political parties as essential to government, and the arch-conservative genrō, Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo, who viewed democratic institutions with skepticism.

During his premierships, Saionji faced the challenge of managing a tight national budget against the military's relentless demands for expansion, particularly from the Army. His first cabinet fell in 1908 due to pressure from conservatives led by Yamagata, who were concerned about the growth of communism and socialism and felt the government's response to social unrest was insufficient.

The collapse of his second cabinet in 1912 marked a significant setback for constitutional government, igniting the Taishō Political Crisis. This crisis stemmed from a bitter dispute over the military budget. The Army Minister, General Uehara, resigned when the cabinet refused to meet the Army's demands. Japanese law stipulated that the Army Minister had to be an active-duty lieutenant general or general. Following Yamagata's instructions, all eligible generals refused to serve in Saionji's cabinet. Consequently, Saionji's cabinet was forced to resign. This incident established a dangerous precedent, demonstrating the military's power to force the resignation of a cabinet. Saionji and Hara Takashi had internal disagreements over railway budget issues, with Hara even submitting his resignation at one point.

3.2. Conflicts with the military and genrō

Saionji's political philosophy, influenced by his court background, dictated that the Imperial Court should be safeguarded from direct political involvement, a strategy that court nobles had employed for centuries in Kyoto. This stance put him at odds with nationalistic elements in the Army who desired the Emperor to actively participate in politics to weaken both the parliament and the cabinet. These nationalists also labeled him a "globalist" for his internationalist views.

After his second cabinet's resignation in December 1912, the public and the Diet strongly reacted against the military's perceived manipulation, leading to the First Constitutional Protection Movement. Although Saionji stepped down as Prime Minister, his influence remained. He participated in the genrō conference to select the next prime minister, where he proposed adopting the British parliamentary system, where the leader of the majority party in the Lower House would automatically become prime minister. While this idea did not gain immediate traction among the genrō, it reflected his consistent advocacy for parliamentary governance.

4. Elder statesman (Genrō) period

As the last surviving genrō, Saionji Kinmochi played a crucial role in Japanese politics for nearly three decades, becoming an influential advisor to the Emperor and striving to uphold constitutional principles amidst the tumultuous rise of militarism.

4.1. Role as the last genrō

Saionji was formally appointed a genrō in December 1912. The role of the genrō was gradually diminishing, but their primary function remained the nomination of prime ministerial candidates to the Emperor for approval-a recommendation that was never rejected. Following the death of Matsukata Masayoshi in 1924, Saionji became the sole surviving genrō. He continued to exercise this prerogative of selecting prime ministers almost until his death in 1940 at the age of 90. Saionji generally favored nominating the president of the majority party in the Diet as prime minister, aligning with his parliamentary ideals. However, his power was consistently constrained by the need for at least the tacit consent of the Army and Navy. He would nominate military men or non-party politicians when he deemed it necessary to ensure an effective government.

His residence, the Zagyosō (坐漁荘ZagyosōJapanese) in Okitsu, became a significant political hub, attracting prominent figures from political and financial circles for consultations in what was known as "Okitsu-mōde" (pilgrimage to Okitsu). He also had private secretaries, such as Kumao Harada, who recorded his views on political matters. After Yamagata Aritomo's death in 1922, Yamagata's private secretary, Gokichi Matsumoto, was instructed to serve Saionji, further solidifying Saionji's position as the leading genrō. Saionji explicitly recognized himself as Yamagata's successor, taking on the responsibility of guiding the Imperial Court and political affairs.

4.2. International diplomacy and racial equality proposal

In 1919, Saionji led the Japanese delegation to the Paris Peace Conference following World War I. Although ill health limited his active participation, his presence held significant symbolic weight. During the negotiations, Saionji proposed the inclusion of a racial equality clause in the Covenant of the League of Nations. However, this proposal faced strong opposition from American and Australian delegations, both of which had policies of racial segregation, and it was ultimately not adopted. Saionji, who was unmarried at 70, was accompanied to Paris by his son, a favorite daughter, his current mistress, and even a chef from the famous Nadaman restaurant to host Japanese food parties. For his lifetime of public service, he was granted the title of kōshaku (Prince) in 1920.

5. Philosophy and ideology

Saionji Kinmochi's political thought was characterized by a strong commitment to liberal principles, a belief in the necessity of parliamentary government, and a steadfast internationalist outlook that often put him at odds with the rising tide of Japanese nationalism and militarism.

5.1. Liberalism and parliamentarism

Saionji's fundamental belief in liberal principles was a cornerstone of his political career. His long immersion in French political thought, particularly during his student years in Paris, deeply influenced his conviction in the importance of parliamentary democracy. He was a rare voice among his generation of Japanese statesmen who actively championed the idea that the political party holding the majority in the House of Representatives should form the cabinet, a concept known as the "constitutional convention" (Kensei no Jōdō). He believed that this system was crucial for a stable and legitimate government.

Even when political circumstances forced him to accept non-party prime ministers or to compromise with military demands, Saionji consistently articulated his preference for party-based cabinets. His efforts to ensure the succession of party leaders, such as Takahashi Korekiyo and Wakatsuki Reijirō, after political crises demonstrated his commitment to this ideal. The New York Times obituary for Saionji fittingly described him as a figure who represented "parliamentary Japan."

5.2. Internationalism and anti-militarism

Saionji was a staunch internationalist, a perspective solidified by his extensive travels and studies in Europe. He frequently emphasized the importance of understanding and adapting to "the world's major trends" (sekai no taisei). His foreign policy perspective consistently prioritized international cooperation, particularly fostering friendly relations with Great Britain and the United States. He firmly believed that aligning with European powers like France or Italy would not benefit Japan's progress, openly stating that such alliances would be detrimental.

He viewed the rising tide of Japanese nationalism, especially after the First Sino-Japanese War, with concern, advocating for a healthy form of nationalism that respected other nations' sovereignty while enabling Japan's independence and development. His opposition to Japanese nationalism and military expansion was a defining feature of his career. This stance often led to him being criticized by the military and ultranationalists, who pejoratively labeled him a "globalist" for his pro-Western and internationalist views. Despite his strong convictions, he often had to pick his battles, conceding defeat when he knew he could not prevent certain outcomes, such as the signing of the Tripartite Pact, which he vociferously opposed.

5.3. Views on the Imperial Court

A central tenet of Saionji's philosophy was his strong belief in preventing the Emperor from directly participating in politics. Drawing on centuries of court tradition, he argued that direct imperial involvement would diminish the Emperor's sacred authority and expose the Imperial Court to political criticism and potential missteps. He viewed the Emperor as an absolute authority whose actions, if political, could not be easily rectified without undermining the imperial institution itself.

This principle was evident in his opposition to Emperor Shōwa's direct questioning or admonition of Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi following the **Huanggutun (Manchurian) incident**. Saionji believed that such imperial intervention would implicate the Emperor in political failures, ultimately harming the imperial image. He held that the Emperor should be a constitutional monarch, guided by the decisions of his subjects rather than directly interfering in administrative matters. Emperor Shōwa's later commitment to this principle of not opposing the decisions of his ministers is believed to have been influenced by Saionji. However, this stance also drew the ire of ultranationalists and radical military factions who desired a more assertive and direct imperial rule, viewing it as a way to circumvent parliamentary processes. As militarism intensified, Saionji reluctantly came to consider that some form of imperial will might need to be expressed, potentially through imperial family members, to counteract military excesses, though he consistently opposed direct involvement by the Emperor himself.

6. Contributions to education

Saionji Kinmochi dedicated significant effort to educational reform, envisioning a modern, inclusive learning system that would prepare Japanese citizens for a globalized world.

6.1. Educational philosophy and reforms

As Minister of Education, Saionji emphasized the cultivation of cultured "citizens." He strongly advocated for the prioritization of science education, English language instruction, and women's education, believing these were crucial for Japan's progress and its ability to interact as an equal with Western nations. He articulated a liberal educational philosophy, stating that education should teach people to "respect each other as equals, to exist themselves, and to allow others to exist."

In 1890, Saionji attempted to revise the **Imperial Rescript on Education**, which had been drafted by figures like Inoue Kowashi. He felt the existing rescript was insufficient and that educational policy needed to be more liberal. His proposed "Second Imperial Rescript on Education" draft notably omitted terms like "loyalty" (chūkō) and "patriotism" (aikoku), focusing instead on enabling all Japanese subjects, including women, to engage equally with citizens of other nations. However, due to his declining health and Itō Hirobumi's concerns about undermining the dignity of the original rescript, the revision was never finalized, though the draft remains preserved at Ritsumeikan University.

6.2. Establishment and support of educational institutions

Saionji Kinmochi played a pivotal role in the establishment and significant support of several key educational institutions in Japan, reflecting his vision for modern learning.

- Ritsumeikan University**: In September 1869, Saionji founded the private school "Ritsumeikan" in his Kyoto residence. Unlike traditional court noble private schools, Ritsumeikan aimed to be a more general educational institution, attracting students from various backgrounds who debated current affairs. However, it was ordered to close by the Kyoto Prefectural Office after less than a year. Saionji regretted its closure and vowed to revive it. His former retainer and private secretary, Nakagawa Kojūrō, later founded the Kyoto Hosei School in 1900, which subsequently inherited the name and spirit of "Ritsumeikan." Although there's no direct organizational continuity, Saionji actively supported Kyoto Hosei School. His younger brothers, Suehiro Takemaro and Sumitomo Tomoito, served on its board and provided substantial financial donations. Saionji also donated numerous books, which formed the "Saionji Bunko" (Saionji Collection) at Ritsumeikan University, helping it meet the requirements for university status. He permitted the use of the Saionji family crest, a left-facing Tomoe, for the school. In 1940, after his death, Ritsumeikan University officially recognized Saionji Kinmochi as its founder. His descendants continue to have ties with the university.

- Kyoto Imperial University** (now Kyoto University): As Minister of Education in 1894, Saionji initiated a plan to expand higher education, prioritizing the establishment of a second imperial university in Kyoto to complement Tokyo Imperial University. This led to the promulgation of the "Imperial Ordinance concerning Kyoto Imperial University" in 1897. Nakagawa Kojūrō, Saionji's private secretary, was appointed the first Director-General of Kyoto Imperial University, overseeing its operations. Kyoto University's founding principle of "freedom of academic pursuit" echoes Saionji and Nakagawa's shared commitment to academic freedom.

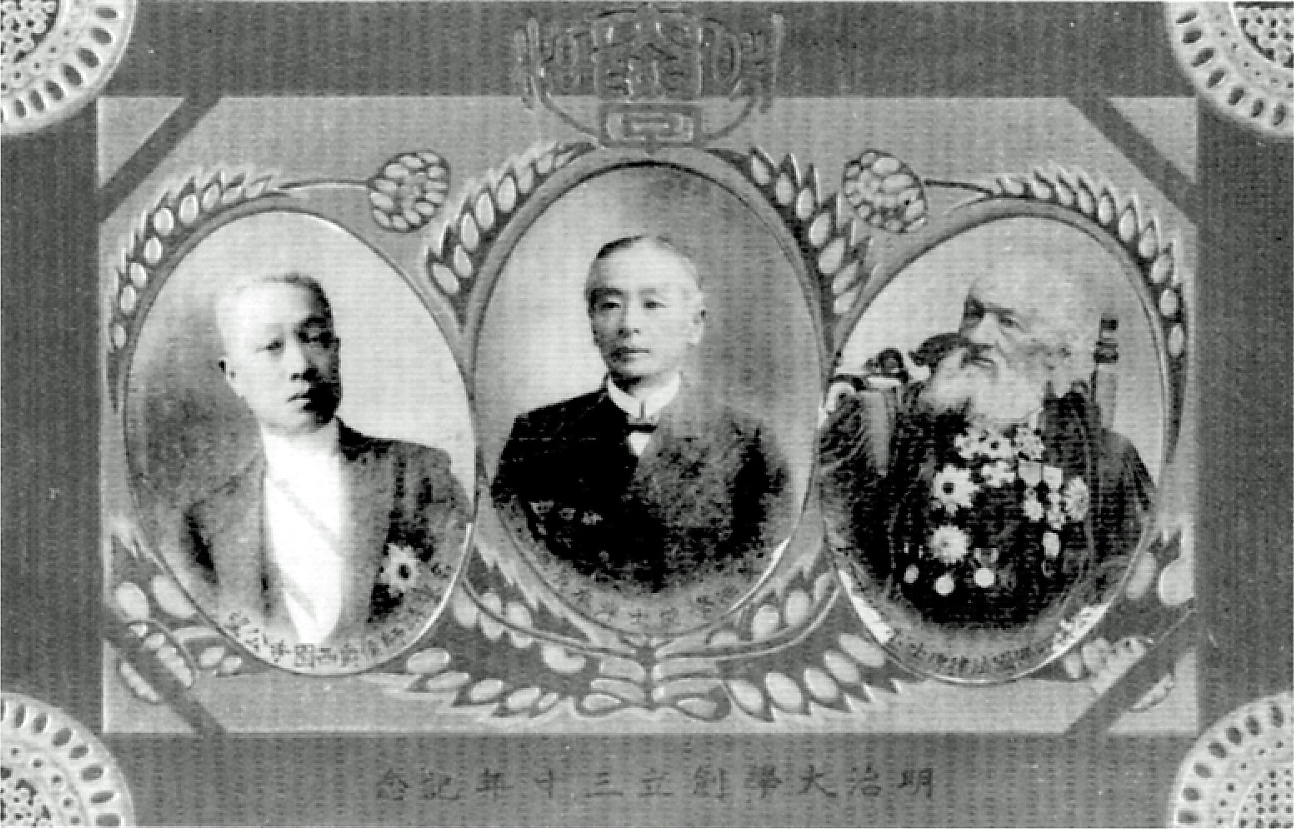

- Meiji University**: In 1881, after his return from France, Saionji was invited to lecture on administrative law at Meiji Law School, the predecessor of Meiji University, founded by his friends Kishimoto Tatsuo, Miyagi Hironaka, and Yashiro Misao. He also served as chairman of its legal debate society. Although he ceased lecturing when he traveled to Europe with Itō Hirobumi in 1882, he maintained an honorary professorship and occasionally attended university events, including its 30th-anniversary celebration. While some historical sources consider him a founder, Meiji University's official stance is that he was a significant contributor and benefactor rather than a direct founder.

- Japan Women's University**: In 1901, Saionji supported the establishment of Japan Women's University, which was championed by Naruse Jinzō. He became a founding promoter and a member of the founding committee for the institution, appointing Nakagawa Kojūrō as the secretary for its establishment.

7. Personal life and anecdotes

Saionji Kinmochi led a colorful private life, marked by his unconventional choices, a strong personality, and a sophisticated taste that sometimes contrasted with his public image as a reserved statesman.

7.1. Family and personal relationships

Saionji never formally married and had no legal wife. Instead, he maintained relationships with several women who were considered his de facto wives.

- Kikuko Kobayashi**: A former geisha from Shinbashi, whom he met in 1881. She was admired for her beauty and wit. She lived with Saionji and even cared for Nakae Chōmin, who lodged upstairs. She bore him a daughter, Shinko. Kikuko primarily resided at Saionji's villa in Ōiso, becoming estranged as Saionji spent more time in Kyoto and Okitsu. She later lived near their daughter Shinko and her husband Hachiro's residence. Their final meeting was in June 1940, shortly before Saionji's death.

- Fusako Nakanishi**: A former geisha from the Nakamura-ya establishment in Shinbashi, she had a daughter, Sonoko, with Saionji. She resided at Saionji's main Tokyo residence in Surugadai and was sometimes referred to as his "first lady" in newspaper reports.

- Hanako Okumura**: The head maid of the Saionji household, Hanako notably accompanied Saionji to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, which caused some controversy. She was described in local reports as a "graceful and modest beauty" and his "mistress." In 1924, she gave birth to a daughter, Kayoko, but Saionji refused to acknowledge her as his own and did not allow her to be registered into his family. Kayoko was subsequently raised by Hanako's brother and his wife. Hanako was expelled from the Saionji household in March 1928 after becoming pregnant by a bank employee. She died of peritonitis in February 1929.

- Ayako Urushiba**: The daughter of a Buddhist temple head priest from Kyoto, she served in the Saionji household during Hanako's time as head maid and had conflicts with her. After Hanako's departure, Ayako became the head maid and was known for her sternness, sometimes causing distress to younger maids, nurses, and even male police officers. Saionji often had to mediate these situations.

Saionji had several children, both biological and adopted:

- Shinko**: Born in 1887 to Kikuko Kobayashi, she was Saionji's daughter. He was highly invested in her education, planning for her to study English or French from a young age. She married Saionji Hachiro, her adoptive cousin, and bore him three sons and three daughters, including Saionji Kōichi and Saionji Fujio. Shinko often served as hostess for her father's parties, showcasing her French language skills. She died in 1920 from the Spanish flu, a loss that deeply saddened Saionji.

- Sonoko**: His daughter with Fusako Nakanishi, who later married Shōichi Takashima.

- Motoko**: An adopted daughter of Saionji.

- Hachiro Saionji**: The eighth son of Mōri Motonori, a former daimyō of the Chōshū Domain, he was adopted by Saionji in 1899. He served as secretary to the Second Katsura Cabinet and later joined the Imperial Household Ministry, accompanying Crown Prince Hirohito (later Emperor Shōwa) on his European tour. After Shinko's death, Hachiro's relationship with Saionji strained, partly due to his involvement in efforts to oust Minister of the Imperial Household Makino Nobuaki, who was allied with Saionji. However, their relationship gradually improved as the political climate became more challenging for Saionji.

- Other adopted children**: Saionji also raised and cared for Mitsusaburō (later Saburō Azumaya), the orphaned son of his close friend Mitsusaburō Kōmyōji. Another relative, Sanetomi Hashimoto, was also temporarily raised by him. These children typically resided in the Gakushūin boarding house during the week and stayed at the Saionji household on weekends.

7.2. Personality and notable anecdotes

Saionji Kinmochi possessed a complex personality, often described as highly intelligent and cultured, yet also capable of surprising wit and a fiery temper beneath a calm exterior.

- Views on Politics**: His mentor Émile Acollas encouraged him to pursue politics, to which Saionji initially replied that politicians often had to lie. Acollas famously countered, "Japanese politicians only sometimes have to lie; French politicians lie all the time," a remark that amused Saionji and underscored their close bond. Saionji once remarked to Ozaki Yukio that politics was a pursuit for "vulgar types" like Itō Hirobumi, indicating his initial disdain for the practical aspects of political life.

- Imperial Favor**: Emperor Meiji reportedly rejoiced at Saionji's appointment as prime minister, noting it was the first time a kuge had reached such a high office.

- Personal Style**: Saionji almost always wore traditional Japanese clothing (wafuku) except when attending court functions, where he adopted Western attire.

- Love for Women**: Like Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru, Saionji was known for his fondness for women and was a frequent patron of hanamachi (geisha districts).

- Health and Longevity**: After a bout of appendicitis in France, Saionji suffered from chronic illnesses, including rheumatism and diabetes. However, his constant attention to his health paradoxically contributed to his longevity.

- Gourmet**: Saionji was a renowned gourmet. During a visit to the Vatican, he was praised for his culinary discernment. He often had chefs dispatched from the prestigious Nadaman restaurant to his home, though few lasted more than a year due to his exacting standards. He enjoyed both high-end dishes like steak and butter-grilled salmon, as well as common fare like Pacific saury. Nishionmatsu, who served as his personal chef from 1931 to 1934, recalled Saionji's particular preference for meticulously prepared brown rice porridge for breakfast.

- Temper**: In private, Saionji was known for his stubbornness and quick temper. His de facto wife Kikuko Kobayashi recounted that avoiding his anger required immense effort, and he rarely praised her even when she performed well, expecting it as a matter of course.

- Reading and Learning**: He was an avid reader, with Konoe Fumimaro noting his profound knowledge of Chinese classics. His extensive collection of French and English books is now housed in the Saionji Bunko at Ritsumeikan University. However, he was reportedly not proficient in traditional Japanese waka poetry, with some of his translations for the Kagerō Nikki containing factual errors.

- Personal Security**: Towards the end of his life, Saionji carried a long, reinforced cane for self-defense, a reflection of the increasing threats he faced from radical elements.

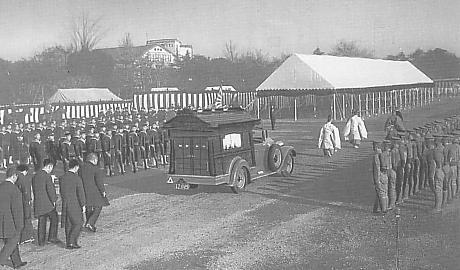

8. Death

Saionji Kinmochi passed away on November 24, 1940, at his residence in Okitsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, at the age of 90 (92 by traditional Japanese reckoning). In the summer of 1940, his health had begun to decline significantly, preventing him from his annual summer retreat to his villa in Gotemba. Instead, air conditioning was installed in his living quarters at Zagyosō. Recognizing that his end was near, he distributed money as mementos to his close associates.

His final public political act was his refusal to recommend Konoe Fumimaro for a third term as prime minister in July 1940, stating his profound disappointment with Konoe's leadership and the direction of the nation. He was deeply critical of the Tripartite Pact, which was signed two months before his death, lamenting it as a "ridiculous" and "foolish" alliance.

Saionji had expressed a wish to avoid traditional Buddhist or Shinto funeral rites, saying, "Even when I die, I will not rely on monks or Shinto priests." He also indicated he did not want a state funeral. However, a grand state funeral was held for him at Hibiya Park in Tokyo on December 5, 1940, attended by tens of thousands of people. On the same day, his Zagyosō villa was opened to the public, drawing 8,000 visitors. He was posthumously elevated to the Junior First Rank and buried at Tama Cemetery in Tokyo, across from the grave of Tōgō Heihachirō.

9. Legacy and historical assessment

Saionji Kinmochi's legacy is complex, marked by widespread admiration for his intellect and international outlook, balanced with criticism regarding the limits of his influence against the burgeoning militarism of his time.

9.1. Overall evaluation and positive reception

Saionji is widely regarded as an intelligent, internationally-minded, deeply learned, and culturally refined individual. He consistently championed liberal principles and parliamentary democracy, a stance that was rare among the leading figures of his generation. He supported the idea that the majority party in the lower house should form the cabinet, an approach that became known as the "constitutional convention" (Kensei no Jōdō).

As the last genrō, he played a crucial role in stabilizing Japanese politics during a turbulent era. He was seen as a neutral mediator, carefully balancing the various factions within the Imperial Court, the government, and the military. His ability to maintain this neutral image, even when holding strong opinions, was a key aspect of his political skill. He was instrumental in advising the Emperor on prime ministerial appointments, often selecting party leaders or figures he believed could maintain stability. He consistently emphasized the importance of international cooperation, particularly with Britain and the United States, and cautioned against excessive nationalism. His influence on Emperor Shōwa's belief in the Emperor's role as a constitutional monarch, not directly involved in political decisions, is also often highlighted as a significant positive contribution.

9.2. Criticism and controversies

Despite his efforts, Saionji faced criticism. Some, like Hara Takashi, his close associate, at times questioned his political acumen, describing him as having "weak will and frequent errors." However, other scholars, like Itō Yukio, argue that this apparent aloofness was a deliberate strategy to maintain his neutrality and authority as a mediator.

His liberal and internationalist views earned him the pejorative label of "worldist" from fervent Japanese militarists and nationalists, who viewed him as being disloyal to the nation's interests. As the military's power grew, Saionji's influence waned, and he was increasingly frustrated by his inability to prevent the country from sliding towards war. His pragmatic compromises, such as nominating non-party figures or acceding to military demands for cabinet appointments, were sometimes seen as concessions that undermined his liberal ideals and eroded his authority among the hardliners. He was also criticized for his stance on the Emperor's role, particularly his opposition to Emperor Shōwa's direct admonition of Prime Minister Tanaka Giichi over the Huanggutun incident. While Saionji intended to protect the Emperor's dignity, this move was perceived by some as undermining the imperial prerogative and emboldening the military.

His personal life, particularly his multiple de facto wives and his decision to bring his mistress to the Paris Peace Conference, also drew some public and journalistic criticism at the time. Ultimately, while Saionji strove to steer Japan toward a parliamentary and internationalist path, his legacy is also one of a statesman who, despite his best efforts, could not fully resist the powerful forces that ultimately led Japan into World War II.

10. Honours

Saionji Kinmochi received numerous titles, decorations, and orders throughout his distinguished career, reflecting his high standing in both Japanese and international society.

10.1. Titles

- Count: July 7, 1884

- Marquess: 1911 (Specific date not mentioned in sources, but confirmed to be between 1884 and 1920)

- Prince (Kōshaku 公爵KōshakuJapanese): September 7, 1920

10.2. Japanese decorations

- Order of the Sacred Treasure: Grand Cordon (June 21, 1895)

- Order of the Rising Sun:

- Third Class (March 11, 1882)

- Second Class (May 29, 1888)

- Grand Cordon (June 5, 1896)

- Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers: Grand Cordon (September 14, 1907)

- Order of the Chrysanthemum:

- Grand Cordon (December 21, 1918)

- Collar (November 10, 1928)

10.3. Foreign decorations

- Order of Pius IX: Knight Grand Cross (February 25, 1888)

- Order of the Iron Crown (Austria): Knight First Class (May 9, 1888)

- Order of the Netherlands Lion: Knight Grand Cross (March 16, 1891)

- Order of the Red Eagle: 1st Class (October 15, 1891)

- Order of Leopold (Belgium): Grand Cordon (July 5, 1892)

- Order of the Medjidie: First Class (March 8, 1894)

- Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus: Knight Grand Cross (March 6, 1896)

- Order of the White Eagle (Russian Empire): (March 17, 1896)

- Legion of Honour (France):

- Grand Officer (July 24, 1896)

- Grand Cross (October 23, 1907)

- Order of Charles III: Grand Cross (November 10, 1896)

- Order of the Dannebrog: Grand Cross (February 10, 1898)

- Order of St Michael and St George: Honorary Knight Grand Cross (GCMG) (February 20, 1906)

- Order of St. Alexander Nevsky: Grand Cordon (October 30, 1907)

- Order of the Double Dragon: First Class, Second Grade (Qing Dynasty) (December 17, 1907)

10.4. Order of precedence

- Senior fifth rank, junior grade: January 21, 1853

- Fifth rank, senior grade: December 27, 1852

- Fourth rank, junior grade: January 22, 1854

- Fourth rank, senior grade: January 22, 1855

- Senior fourth rank, junior grade: February 5, 1856

- Third rank: April 25, 1861

- Senior third rank: July 5, 1862 (relinquished July 3, 1869; restored December 19, 1878)

- Second rank: December 11, 1893

- Senior second rank: December 20, 1898

- Junior First Rank: November 25, 1940 (posthumous)

11. Works

Saionji Kinmochi was also an author, with his primary published work being:

- Tōan Zuihitsu (陶庵随筆Tōan ZuihitsuJapanese, "Essays by Tōan") published in October 1903. This collection compiles essays he wrote for the magazine Sekai no Nihon (Japan and the World). It also includes his "Kaiko-dan" (Reminiscences) and excerpts from his travelogue "Ōroppa Kiyū Bassho" (Notes from a European Journey). The collection was compiled by Kunikida Doppo, who had served as a student in Saionji's household.

12. See also

- List of Prime Ministers of Japan

- Genrō

- Keien era

- Rikken Seiyūkai

- Meiji University

- Ritsumeikan University

- Kyoto University

- Paris Peace Conference (1919-1920)

- February 26 Incident