1. Overview

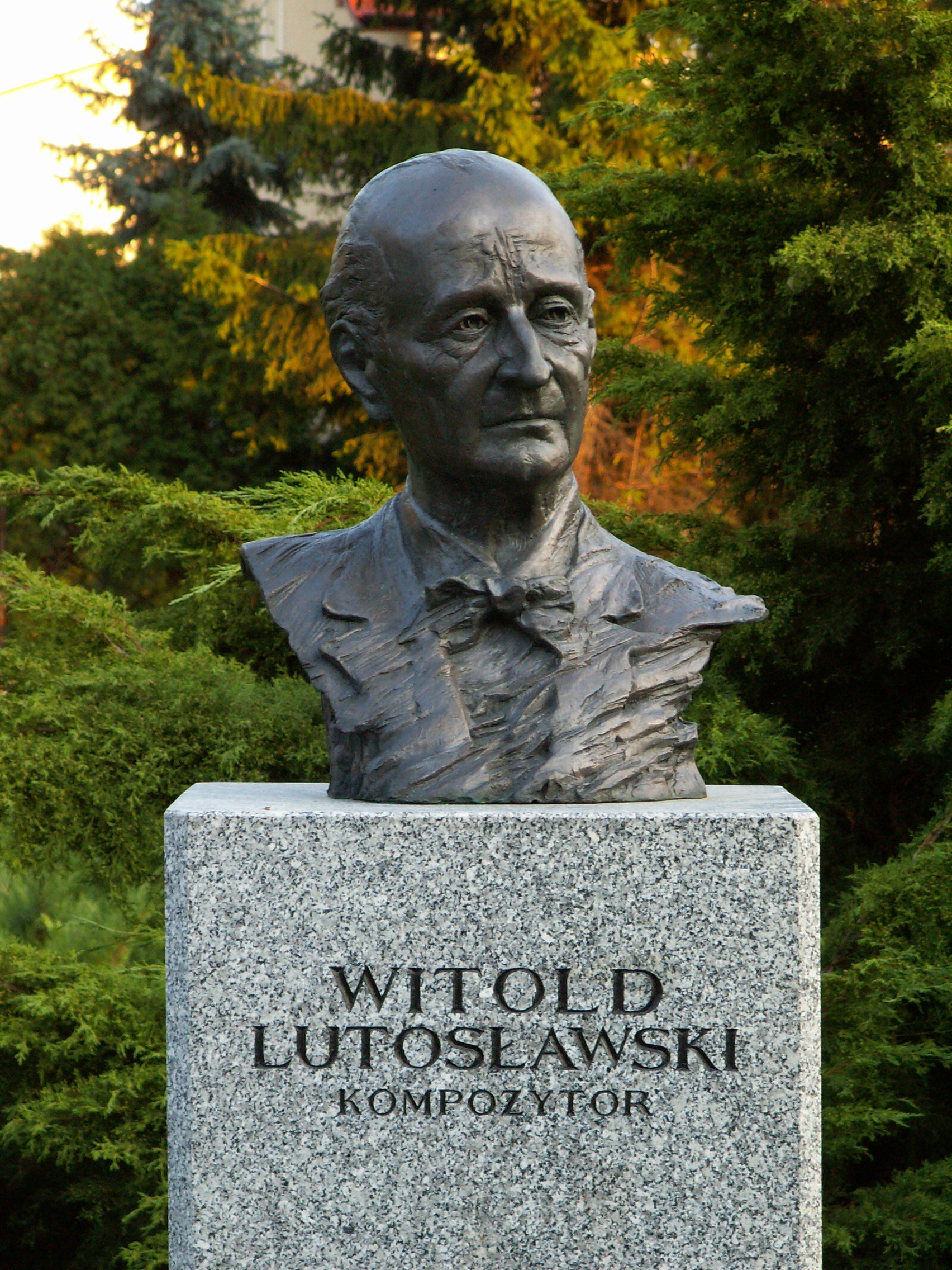

Witold Roman Lutosławski (Witold Roman Lutosławskiˈvitɔld lutɔˈswafskiPolish; 25 January 1913 - 7 February 1994) was a prominent Polish composer and conductor, widely regarded as one of the most significant European composers of the 20th century. He is often considered the most important Polish composer since Karol Szymanowski and possibly the greatest since Frédéric Chopin. Lutosławski's extensive body of work, which he often conducted himself, encompasses most traditional genres except opera, including symphonies, concertos, orchestral song cycles, and chamber works. Among his best-known compositions are his four symphonies, the Variations on a Theme by Paganini (1941), the Concerto for Orchestra (1954), and his Cello Concerto (1970).

Initially influenced by Polish folk music, Lutosławski's early works featured rich, atmospheric textures. From the late 1950s, he developed a unique compositional style, incorporating a distinctive twelve-tone technique based on specific intervals and introducing "limited aleatorism" to allow controlled randomness within his structured compositions. Throughout his career, Lutosławski resolutely maintained his artistic integrity, notably opposing the Stalinist authorities who banned his First Symphony as "formalist." He actively supported the Solidarity movement in the 1980s, refusing professional engagements in Poland as a gesture of defiance. His unwavering commitment to artistic independence and his profound musical contributions earned him numerous international accolades, including the Grawemeyer Award, a Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal, and Poland's highest honor, the Order of the White Eagle.

2. Life and Career

Witold Lutosławski's life and career were marked by significant personal and political challenges, which he navigated with unwavering artistic and moral integrity, ultimately achieving international renown for his innovative compositions.

2.1. Early Life and Education

Witold Roman Lutosławski was born on 25 January 1913, in Warsaw, Poland. His parents, Józef and Maria Olszewska, were both from the Polish landed nobility and owned estates in Drozdowo. His father, Józef Lutosławski, was actively involved in the Polish National Democratic Party (Endecja) and was close to its founder, Roman Dmowski, after whom Witold received his middle name. Józef met Maria while studying in Zürich in 1904, and he later pursued further studies in London, working as a correspondent for the National-Democratic newspaper Goniec. He continued his political involvement after returning to Warsaw in 1905 and took over the family estates in 1908. Witold, the youngest of three brothers, was born shortly before the outbreak of World War I.

In 1915, as Prussian forces advanced towards Warsaw during World War I, the Lutosławski family relocated to Moscow. Józef remained politically active there, organizing Polish Legions with the aim of liberating Poland, which had been divided for over a century. However, the February Revolution of 1917, which led to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, and the subsequent October Revolution that established the Soviet government, brought Józef into conflict with the Bolsheviks. He and his brother Marian were arrested and interned in Butyrskaya prison in central Moscow. Five-year-old Witold visited his father there. In September 1918, Józef and Marian were executed by a firing squad, just days before their scheduled trial.

After the war, the family returned to the newly independent Poland, only to find their estates in ruins. Following his father's death, other family members, particularly Józef's half-brother Kazimierz Lutosławski, a priest and politician, played a significant role in Witold's early life. At age six, Lutosławski began two years of piano lessons in Warsaw. After the Polish-Soviet War, the family briefly returned to Drozdowo but, facing limited success in managing the estates, his mother moved back to Warsaw, working as a physician and translating children's books from English.

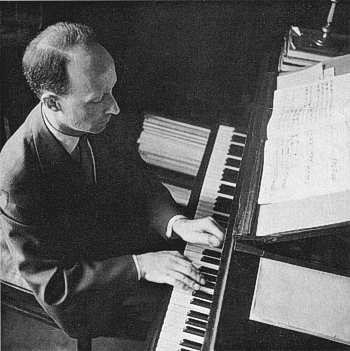

In 1924, Lutosławski entered the Stefan Batory Gymnasium while continuing his piano studies. A performance of Karol Szymanowski's Third Symphony profoundly impacted him. In 1925, he began violin lessons at the Warsaw Music School. In 1931, he enrolled at Warsaw University to study mathematics, and in 1932, he formally joined the composition classes at the Warsaw Conservatory. His sole composition teacher was Witold Maliszewski, a renowned Polish composer and a pupil of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Maliszewski provided Lutosławski with a strong foundation in musical structures, especially movements in sonata form. In 1932, he abandoned the violin, and in 1933, he discontinued his mathematics studies to fully dedicate himself to piano and composition. He earned a diploma for piano performance from the Conservatory in 1936, after presenting a virtuoso program including Schumann's Toccata and Beethoven's fourth piano concerto. He received his composition diploma from the same institution in 1937.

2.2. World War II and Occupation

Following his studies, Lutosławski completed his military service, receiving training in signaling and radio operation in Zegrze near Warsaw. He completed his Symphonic Variations in 1939, a work that was premiered by the Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Grzegorz Fitelberg, and broadcast on 9 March 1939. Lutosławski had plans to continue his musical education in Paris, but these were thwarted in September 1939 when Germany invaded western Poland and the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland.

Mobilized with the radio unit for the Kraków Army, Lutosławski was soon captured by German soldiers. However, he managed to escape while being marched to a prison camp, walking an arduous 249 mile (400 km) back to Warsaw. Tragically, his brother was captured by Russian soldiers and later died in a Siberian labor camp.

To support himself during the German occupation, Lutosławski joined the "Dana Ensemble" as an arranger-pianist, performing in the "Ziemiańska Cafe." He then formed a piano duo with his friend and fellow composer Andrzej Panufnik, performing regularly in Warsaw cafés. Their repertoire included a wide range of music in their own arrangements, notably the first version of Lutosławski's Variations on a Theme by Paganini, a transcription of Niccolò Paganini's 24th Caprice for solo violin. Defiantly, they sometimes played Polish music, which the Nazis had banned in Poland (including works by Frédéric Chopin), and even composed Resistance songs. During this period, listening to music in cafés was the only way for Poles in German-occupied Warsaw to hear live music, as organized concerts were prohibited. It was in the café Aria, where they performed, that Lutosławski met his future wife, Maria Danuta Bogusławska, the sister of writer Stanisław Dygat.

In July 1944, just days before the Warsaw Uprising, Lutosławski left Warsaw with his mother. During the subsequent complete destruction of the city by the Germans after the uprising's failure, most of his music was lost, as were the family's Drozdowo estates. He managed to salvage only a few scores and sketches. Of the approximately 200 arrangements that Lutosławski and Panufnik had created for their piano duo, only Lutosławski's Variations on a Theme by Paganini survived. Following the Polish-Soviet treaty in April 1945, Lutosławski returned to the ruins of Warsaw.

2.3. Post-War Poland and Political Challenges

In the immediate post-war years, Lutosławski dedicated himself to completing his First Symphony, which he had begun in 1941 and whose sketches he had salvaged from Warsaw's destruction. It premiered in 1948, conducted by Fitelberg. To support his family, he also composed what he termed "functional" music, such as the Warsaw Suite (written to accompany a silent film depicting the city's reconstruction), collections of Polish Carols, and piano study pieces like Melodie Ludowe ("Folk Melodies").

In 1945, Lutosławski was elected as secretary and treasurer of the newly formed Union of Polish Composers (ZKP-Związek Kompozytorów Polskich). The following year, in 1946, he married Danuta Bogusławska. Their marriage was enduring, and Danuta's exceptional drafting skills proved invaluable to the composer; she became his copyist and played a crucial role in solving some of the complex notational challenges of his later works.

The Stalinist political climate intensified in 1947, leading to the imposition of socialist realism by the ruling Polish United Workers' Party. This artistic censorship, which originated directly from Stalin and was prevalent across the Eastern Bloc, was further enforced by the 1948 Zhdanov decree. By 1948, the ZKP was dominated by musicians who adhered to the party line on musical matters. Lutosławski, who was implacably opposed to the tenets of socialist realism, resigned from the committee. He viewed the abandonment of recent decades' musical achievements for a return to 19th-century musical language as an "absurd hypothesis" that caused "immense harm" to Polish music.

Lutosławski's First Symphony was proscribed as "formalist," a label that led to his ostracization by Soviet authorities, a situation that persisted through the eras of Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko. In 1954, the oppressive musical climate prompted his friend Andrzej Panufnik to defect to the United Kingdom. Despite this, Lutosławski continued to compose pieces for which there was a social demand. However, in 1954, he received the Prime Minister's Prize for a set of children's songs, an award he accepted with considerable chagrin. He commented that he realized he was not merely writing "indifferent little pieces" for a living, but was, in the eyes of the outside world, engaging in "artistic creative activity."

It was his substantial and original Concerto for Orchestra of 1954 that truly established Lutosławski as an important composer of art music. The work, commissioned in 1950 by conductor Witold Rowicki for the newly reconstituted Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, earned the composer two state prizes the following year.

2.4. Development of Compositional Techniques

The death of Stalin in 1953 brought a degree of relaxation to the cultural totalitarianism in Russia and its satellite states. By 1956, political developments had led to a partial thawing of the musical climate, culminating in the establishment of the Warsaw Autumn Festival of Contemporary Music. Conceived as a biennial event, it has been held annually since 1958 (except in 1982, when the ZKP refused to organize it in protest against Martial law).

The first performance of his Musique funèbre (Polish: Muzyka żałobna, English: Funereal Music or Music of Mourning) took place in 1958. This work, written to commemorate the 10th anniversary of Béla Bartók's death, took Lutosławski four years to complete. It garnered him international recognition, along with the annual ZKP prize and the International Rostrum of Composers prize in 1959. In this work, and in the Five Songs of 1956-57, Lutosławski significantly developed his harmonic and contrapuntal thinking, introducing his unique twelve-note system, which was the culmination of many years of thought and experimentation.

Another new feature that became a Lutosławski signature was the introduction of randomness into the exact synchronisation of various parts of the musical ensemble, first showcased in Jeux vénitiens ("Venetian Games"). These harmonic and temporal techniques became integral to his style and were incorporated into every subsequent work.

2.5. International Recognition and Mature Period

From 1957 to 1963, Lutosławski also composed light music under the pseudonym Derwid, a departure from his typically serious compositions. These pieces, mostly waltzes, tangos, foxtrots, and slow-foxtrots for voice and piano, fall into the genre of Polish "actors' songs." Their presence in his output is less incongruous considering his own performances of cabaret music during the war and his familial connection to the famous Polish cabaret singer Kalina Jędrusik, his wife's sister-in-law.

In 1963, Lutosławski completed a commission for the Music Biennale Zagreb, his Trois poèmes d'Henri Michaux for chorus and orchestra. This was his first work commissioned from abroad and brought him further international acclaim. It earned him a second State Prize for music (an award he was not cynical about this time), and he secured an agreement for the international publication of his music with Chester Music, then part of the Hansen publishing house. His String Quartet premiered in Stockholm in 1965, followed the same year by the first performance of his orchestral song-cycle Paroles tissées. The shortened title was suggested by the poet Jean-François Chabrun, who had published the poems as Quatre tapisseries pour la Châtelaine de Vergi. The song cycle is dedicated to the tenor Peter Pears, who first performed it at the 1965 Aldeburgh Festival with the composer conducting. The Festival was founded and organized by Benjamin Britten, with whom Lutosławski formed a lasting friendship.

Shortly thereafter, Lutosławski began work on his Second Symphony, which had two premieres: Pierre Boulez conducted the second movement, Direct, in 1966, and when the first movement, Hésitant, was finished in 1967, the composer conducted a complete performance in Katowice. The Second Symphony significantly deviates from a conventional classical symphony in structure, with Lutosławski employing his many compositional innovations to construct a large-scale, dramatic work. In 1968, the Symphony earned Lutosławski first prize from the International Music Council's International Rostrum of Composers, his third such award, confirming his burgeoning international reputation. In 1967, Lutosławski was awarded the Léonie Sonning Music Prize, Denmark's highest musical honor. He also received the Herder Prize from the University of Vienna in 1967.

The Second Symphony, along with Livre pour orchestre and a Cello Concerto, were composed during a particularly traumatic period for Lutosławski. His mother died in 1967, and Poland experienced significant unrest from 1967 to 1970. This included the suppression of the theatre production Dziady, which ignited protests, the use of Polish troops to suppress liberal reforms during Czechoslovakia's Prague Spring in 1968, and the Gdańsk Shipyard strike of 1970, which led to a violent government crackdown. Lutosławski, who did not support the Soviet regime, was deeply affected by these events, which are believed to have contributed to the increased antagonistic effects in his work, particularly the Cello Concerto of 1968-70, written for Rostropovich and the Royal Philharmonic Society. Rostropovich himself was a vocal opponent of the Soviet regime and soon after declared his support for the dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. While Lutosławski acknowledged these events impinged on his creative world, he did not believe they had a direct, causal effect on his music. Nevertheless, the Cello Concerto was a great success, earning accolades for both Lutosławski and Rostropovich. At its premiere with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Arthur Bliss presented Rostropovich with the Royal Philharmonic Society's gold medal.

In 1973, Lutosławski attended a recital in Warsaw given by baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with pianist Sviatoslav Richter, which inspired him to write his extended orchestral song Les Espaces du sommeil ("The spaces of sleep"). This work, along with Preludes and Fugue, Mi-Parti (a French expression meaning "divided into two equal but different parts"), Novelette, and a short piece for cello in honor of Paul Sacher's seventieth birthday, occupied Lutosławski throughout the 1970s. During this time, he was also working on a projected Third Symphony and a concertante piece for oboist Heinz Holliger, finding them difficult to complete as he sought to introduce greater fluency into his sound world and reconcile tensions between the harmonic and melodic aspects of his style, as well as between foreground and background elements. The Double Concerto for oboe, harp and chamber orchestra, commissioned by Sacher, was finally finished in 1980, and the Third Symphony in 1983. In 1977, he received the Order of the Builders of People's Poland, and in 1983, the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize.

During this period, Poland experienced further upheaval: the influential Solidarność movement was formed in 1980, led by Lech Wałęsa, and martial law was declared by General Wojciech Jaruzelski in 1981. From 1981 to 1989, Lutosławski refused all professional engagements in Poland as a gesture of solidarity with the artists' boycott. He declined to meet government ministers at the Culture Ministry and carefully avoided being photographed in their company. In a significant gesture of support in 1983, he sent a recording of the first performance (in Chicago) of his Third Symphony to Gdańsk to be played to strikers in a local church. In 1983, he was awarded the Solidarity prize, an honor of which he was reportedly prouder than any other.

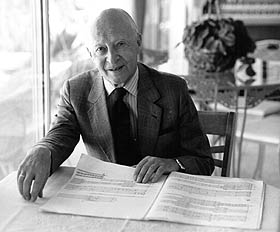

2.6. Final Years and Death

Through the mid-1980s, Lutosławski composed three pieces titled Łańcuch ("Chain"), a name that refers to the way the music is constructed from contrasting strands that overlap like the links of a chain. Chain 2 was written for Anne-Sophie Mutter (commissioned by Sacher), and for Mutter, he also orchestrated his slightly earlier Partita for violin and piano, adding a new linking Interlude. When played together, the Partita, Interlude, and Chain 2 form his longest work.

In 1985, the Third Symphony earned Lutosławski the first Grawemeyer Prize from the University of Louisville, Kentucky. The prize's significance lay not only in its prestige but also in its substantial financial award, then 150.00 K USD. The award is intended to relieve recipients' financial concerns, allowing them to concentrate on serious composition. In a gesture of altruism, Lutosławski announced that he would use the funds to establish a scholarship enabling young Polish composers to study abroad. He also directed that his fee from the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra for Chain 3 should go to this scholarship fund.

In 1986, Lutosławski was presented with the rarely awarded Royal Philharmonic Society's Gold Medal by Michael Tippett during a concert where Lutosławski conducted his Third Symphony. That same year, a major celebration of his work was held at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. Additionally, he received honorary doctorates from several universities worldwide, including Cambridge.

At this time, Lutosławski was composing his Piano Concerto for Krystian Zimerman, commissioned by the Salzburg Festival. His earliest plans to write a piano concerto dated back to 1938, reflecting his own virtuosity as a pianist in his younger days. A performance of this work and the Third Symphony at the Warsaw Autumn Festival in 1988 marked the composer's return to the conductor's podium in Poland, following substantive talks between the government and the opposition.

Around 1990, Lutosławski also worked on his Fourth Symphony and his orchestral song-cycle Chantefleurs et Chantefables for soprano. The latter premiered at a Prom concert in London in 1991, and the Fourth Symphony premiered in Los Angeles in 1993. In between these compositions, and after initial reluctance, Lutosławski assumed the presidency of the newly reconstituted "Polish Cultural Council," established after the 1989 legislative elections led to the end of communist rule in Poland.

In 1993, Lutosławski maintained a busy schedule, traveling to the United States, England, Finland, Canada, and Japan, and sketching a violin concerto. However, by the first week of 1994, it became clear that cancer had taken hold. After an operation, the composer rapidly weakened and died on 7 February 1994, at the age of 81. Just a few weeks prior, he had been awarded Poland's highest honor, the Order of the White Eagle, becoming only the second person to receive this distinction since the collapse of communism in Poland (the first being Pope John Paul II). He was cremated, and his devoted wife, Danuta, died shortly thereafter.

3. Musical Style and Philosophy

Lutosławski viewed musical composition as a search for listeners who shared his thoughts and feelings, once describing it as "fishing for souls." He believed this connection could only be achieved through "the greatest artistic sincerity in every detail of music, from the minutest technical aspects to the most secret depths," and considered creative activity to be "the best medicine for loneliness."

3.1. Folk Music Influence

Lutosławski's works up to and including the Dance Preludes (1955) demonstrate the influence of Polish folk music, both harmonically and melodically. A key aspect of his artistry was his ability to transform folk music rather than simply quoting it directly. In some cases, such as the Concerto for Orchestra, the folk music elements are unrecognizable without careful analysis, as they are radically transformed and manipulated to serve the composer's artistic vision. This approach allowed him to create a style that was both demonstrably "national" and politically unassailable, yet modern and personal enough to transcend the bounds of socialist realism. As Lutosławski developed the techniques of his mature compositions, he gradually moved away from explicitly using folk material, though its subtle influence remained until the end of his career. He stated that in his early period, he "could not compose as I wished, so I composed as I was able," and regarding his change of direction, he simply said, "I was not so interested in it [using folk music]." Lutosławski was also dissatisfied with composing in a "post-tonal" idiom, feeling that his First Symphony, in this regard, led him to a cul-de-sac. Consequently, Dance Preludes became his final composition explicitly centered around folk music, which he described as a "farewell to folklore."

3.2. Pitch Organization and Harmony

In Five Songs (1956-57) and Musique funèbre (1958), Lutosławski introduced his distinctive approach to twelve-tone music, marking his definitive departure from the explicit use of folk music. His twelve-tone technique allowed him to construct harmony and melody from specific intervals (for instance, augmented fourths and semitones in Musique funèbre). This system also provided him with the means to write dense chords without resorting to tone clusters, enabling him to build towards these dense chords (which often include all twelve notes of the chromatic scale) at climactic moments. Lutosławski's twelve-note techniques were fundamentally different in conception from Arnold Schoenberg's tone-row system, although Musique funèbre does happen to be based on a tone row. This twelve-note intervallic technique had its genesis in earlier works such as his First Symphony and Variations on a Theme by Paganini, where symmetrical chords and specific pitch organizations were already explored.

3.3. Aleatory Technique

Although Musique funèbre received international acclaim, Lutosławski faced a compositional crisis, struggling to find a way to fully express his musical ideas despite his new harmonic techniques. On 16 March 1960, while listening to a Polish Radio broadcast of new music, he heard John Cage's Concert for Piano and Orchestra. While not influenced by the sound or philosophy of Cage's music, Cage's explorations of indeterminacy sparked a train of thought that led Lutosławski to discover a method for retaining his desired harmonic structures while introducing the freedom he sought. Consequently, his Three Postludes were hastily concluded (he had intended to write four), and he proceeded to compose works exploring these new ideas.

In works from Jeux vénitiens onwards, Lutosławski incorporated long passages where the parts of the ensemble are not precisely synchronized. At cues from the conductor, each instrumentalist might be instructed to move directly to the next section, finish their current section before proceeding, or stop. In this manner, the random elements, defined by the term aleatory, are carefully directed within compositionally controlled limits. The composer maintains precise control over the piece's architecture and harmonic progression. Lutosławski notated the music exactly, with no improvisation or choice of parts given to any instrumentalist, ensuring there is no doubt about how the musical performance is to be realized.

For his String Quartet, Lutosławski initially provided only the four individual instrumental parts, refusing to bind them into a full score. He was concerned that a conventional score would imply that vertically aligned notes should coincide, as is typical in traditionally notated classical ensemble music. However, the LaSalle Quartet specifically requested a score to prepare for the first performance. His wife, Danuta Lutosławska, ingeniously solved this problem by cutting up the parts and reassembling them into "boxes" (which Lutosławski called mobiles), with instructions on how the conductor should signal when all players should proceed to the next mobile. In his orchestral music, these notational challenges were less severe, as the conductor provides instructions on how and when to proceed. Lutosławski referred to this technique of his mature period as "limited aleatorism."

Both Lutosławski's harmonic and aleatory processes are illustrated by Example 1, an excerpt from Hésitant, the first movement of his Symphony No. 2. At number 7, the conductor cues the flutes, celesta, and percussionist, who then play their parts at their own pace, without attempting to synchronize with other instrumentalists. The harmony of this section is based on a 12-note chord constructed from major seconds and perfect fourths. After all instrumentalists have completed their parts, a two-second general pause is indicated. The conductor then cues at number 8 (and indicates the tempo of the following section) for two oboes and the cor anglais. They each play their part, again without synchronizing with other players. The harmony here is based on the hexachord F♯-G-A♭-C-D♭-D, arranged so that the section's harmony never includes any sixths or thirds. When the conductor gives another cue at number 9, the players continue until they reach the repeat sign and then stop; they are unlikely to end the section simultaneously. This "refrain" (from numbers 8 to 9) recurs throughout the movement, slightly altered each time, but always played by double-reed instruments that do not appear elsewhere in the movement, demonstrating Lutosławski's careful control of the orchestral palette.

3.4. Compositional Philosophy and Artistic Integrity

Lutosławski's formidable technical developments stemmed from his profound creative imperative. The lasting body of major compositions he left behind stands as a testament to his unwavering resolution in the face of the anti-formalist authorities under which he formulated his methods. He is greatly admired for the musical and moral integrity of his long and often difficult journey to discover a personal language and consummate technique that served his unique artistic voice.

4. Major Works

Lutosławski's oeuvre spans a wide range of genres, showcasing his evolving style and innovative techniques.

4.1. Symphonies

Lutosławski composed four symphonies, each marking a significant stage in his compositional development:

- Symphony No. 1 (1941-1947)

- Symphony No. 2 (1966-1967)

- Symphony No. 3 (1974-1983)

- Symphony No. 4 (1993)

4.2. Orchestral Works

Beyond his symphonies, Lutosławski wrote numerous other significant orchestral compositions:

- Symphonic Variations (1938)

- Overture (1949)

- Little Suite (1950)

- Concerto for Orchestra (1950-1954)

- Musique funèbre (Funereal Music) (1958)

- Three Postludes (1958-1960)

- Jeux vénitiens (Venetian Games) (1961)

- Livre pour orchestre (1968)

- Preludes and Fugue (1972)

- Mi-Parti (1976)

- Novelette (1978-1979)

- Chain 3 (1986)

4.3. Concertos

Lutosławski's concertos are notable for their dramatic character and the virtuosic demands placed on the soloists:

- Concerto for Orchestra (1950-1954) - while titled a concerto, it functions as a large-scale orchestral work.

- Cello Concerto (1970) - written for Mstislav Rostropovich.

- Double Concerto for oboe, harp and chamber orchestra (1979-1980) - commissioned by Paul Sacher.

- Chain 2 (1985) - a concertante piece for violin and orchestra, written for Anne-Sophie Mutter.

- Piano Concerto (1988) - written for Krystian Zimerman.

4.4. Chamber and Solo Works

Lutosławski's chamber and solo compositions demonstrate his meticulous approach to texture and form on a smaller scale:

- Woodwind Trio (1945)

- Bucolics (1952)

- Dance Preludes (1954-1955) - for clarinet and piano (or orchestra).

- String Quartet (1964)

- Sacher Variations (1975) - for cello solo.

- Epitaph (1979) - for oboe and piano.

- Chain 1 (1983) - for 14 instruments.

- Partita (1988) - for violin and piano (later orchestrated with an Interlude for violin and orchestra).

- Piano Sonata (1934)

- Variations on a Theme by Paganini (1941) - for two pianos (later arranged for piano and orchestra).

4.5. Vocal and Choral Works

Lutosławski's vocal and choral compositions often feature rich orchestral accompaniment and expressive vocal lines:

- Three Christmas Carols (1946)

- Songs for Children (1951)

- Five Songs (1956-1957) - for soprano and piano (or orchestra).

- Trois poèmes d'Henri Michaux (Three Poems of Henri Michaux) (1963) - for chorus and orchestra.

- Paroles tissées (Woven Words) (1965) - song cycle for tenor and chamber orchestra.

- Les Espaces du sommeil (The Spaces of Sleep) (1975) - for baritone and orchestra.

- Chantefleurs et Chantefables (Songflowers and Songfables) (1991) - song cycle for soprano and orchestra.

5. Legacy

In the 21st century, Witold Lutosławski is generally considered the most important Polish composer since Karol Szymanowski, and potentially the most outstanding since Frédéric Chopin. This high regard was not immediately apparent after World War II, when Andrzej Panufnik was initially more highly esteemed in Poland. However, the international success of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra and Panufnik's defection to England in 1954 brought Lutosławski to the forefront of modern Polish classical music.

Initially, Lutosławski was often associated with his younger contemporary Krzysztof Penderecki due to shared stylistic and technical characteristics in their music. However, as Penderecki's reputation experienced a decline in the 1970s, Lutosławski emerged as the preeminent Polish composer of his time and one of the most significant 20th-century European composers. His four symphonies, the Variations on a Theme by Paganini (1941), the Concerto for Orchestra (1954), and his Cello Concerto (1970) remain his most widely recognized and performed works. Above all, he is admired for the profound musical and moral integrity that characterized his long search for a personal language and a consummate technique, which served his individual artistic voice throughout his career.

6. Awards and Honours

Witold Lutosławski received numerous prestigious awards, honorary degrees, and distinctions throughout his career, recognizing his immense contributions to music:

- Order of Polonia Restituta (1953)

- Order of the Banner of Work (1955)

- Związek Kompozytorów Polskich (ZKP) Prize (1959)

- First Prize of the International Music Council's International Rostrum of Composers (1959, 1962, 1964, 1968)

- Koussevitzky Prix Mondial du Disque (France) (1964, 1976, 1986)

- Grand Prix du Disque de Académie Charles Cros (France) (1965, 1971)

- Jurzykowski Prize (United States) (1966)

- Herder Prize (Germany/Austria) (1967)

- Léonie Sonning Music Prize (Denmark) (1967)

- Prix Maurice Ravel (France) (1971)

- Honorary member of the Polish Composers' Union (1971)

- Wihuri Sibelius Prize (Finland) (1973)

- Honorary degree of the University of Warsaw (1973)

- Order of the Builders of People's Poland (1977)

- Honorary degree of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń (1980)

- Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (Germany) (1983)

- Honorary doctorate, Durham University (1983)

- Solidarity prize (1983)

- Honorary degree of the Jagiellonian University (1984)

- Queen Sofía Composition Prize (Spain) (1985)

- Grawemeyer Award (United States) (1985)

- Royal Philharmonic Society Gold Medal (United Kingdom) (1986)

- Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition (1987)

- Honorary doctorate, University of Cambridge (1987)

- Honorary degree of the Fryderyk Chopin University of Music (1988)

- Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts (1993)

- Polar Music Prize (Sweden) (1993)

- Kyoto Prize (Japan) (1993)

- Honorary doctorate, McGill University (1993)

- Order of the White Eagle (Poland) (1994)

Lutosławski also received honorary doctorates from various other institutions, including those in Kraków, Chicago, Glasgow, and Cleveland.