1. Life and Career

Ludwig van Beethoven's life unfolded in distinct phases, from his early years and education in Bonn to his establishment as a composer and his final years of intense creation in Vienna. This chronological journey reveals his development as a musician, his personal struggles, and his unwavering dedication to his art.

1.1. Early Life and Education

Beethoven's early life was marked by a rich musical heritage but also significant family challenges, which shaped his childhood experiences and initial musical training in Bonn.

1.1.1. Birth and Family Background

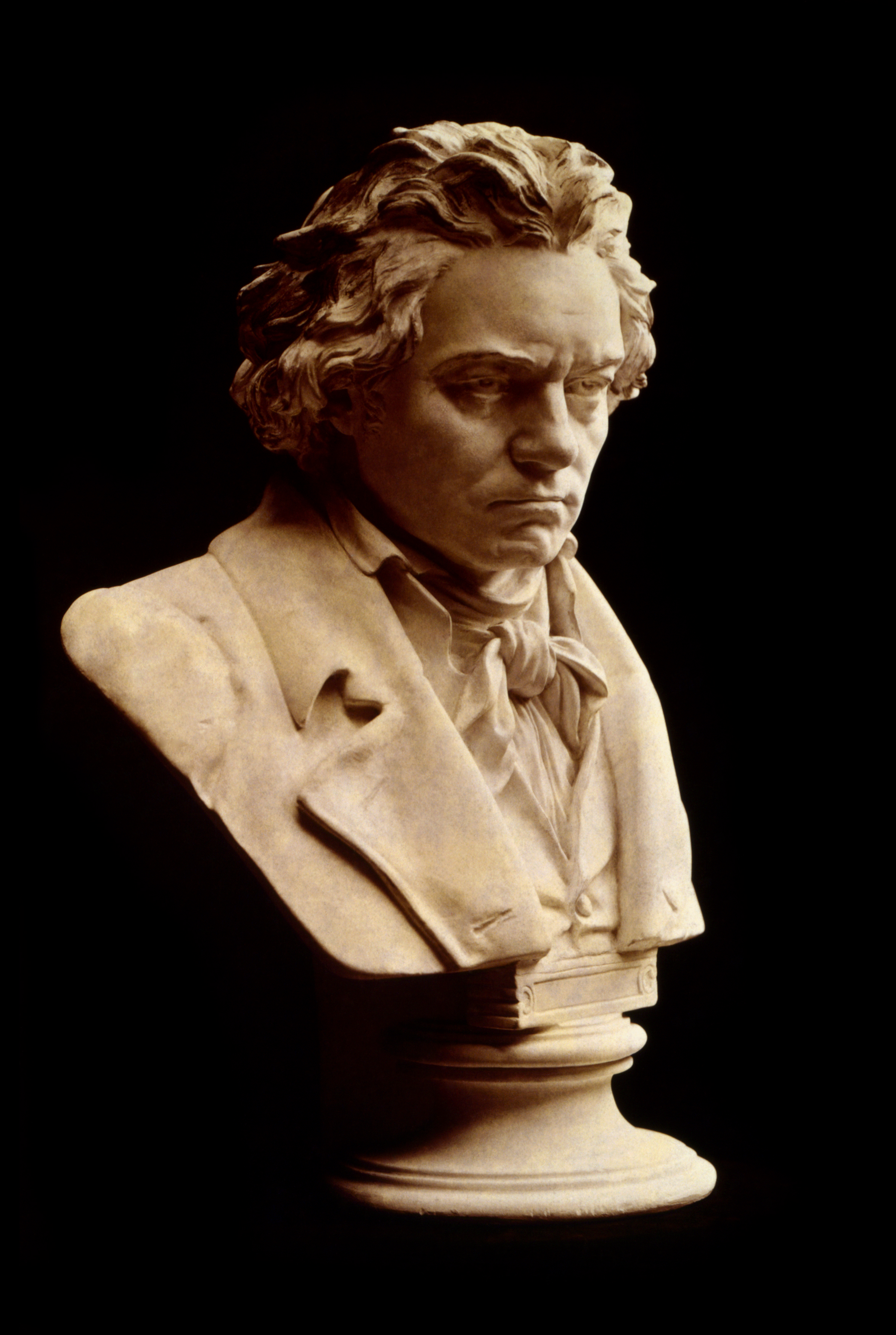

Beethoven was the grandson of Ludwig van Beethoven the Elder, who was a musician from the town of Mechelen in the Austrian Duchy of Brabant, now part of the Flemish region of Belgium. His grandfather moved to Bonn at the age of 21, where he became a prominent musician, eventually rising to the position of Kapellmeister (music director) at the court of Clemens August of Bavaria, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne in 1761. His portrait, commissioned towards the end of his life, remained displayed in his grandson's room as a talisman of his musical heritage, symbolizing the strong musical lineage. Ludwig van Beethoven was born into this musical family in Bonn, at what is now the Beethoven-Haus museum, Bonngasse 20.

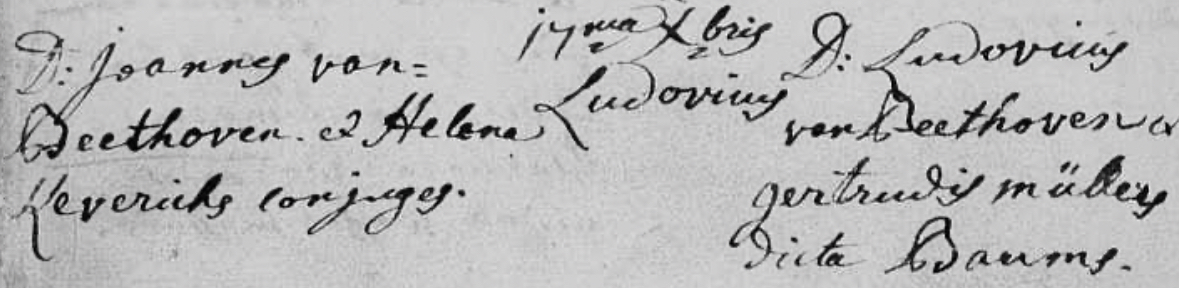

There is no authentic record of his exact birth date, but the registry of his baptism in the Catholic Parish of St. Remigius on December 17, 1770, survives. It was customary in the region at the time to perform baptisms within 24 hours of birth. This led to a consensus, which Beethoven himself agreed with, that his birth date was December 16, though no documentary proof exists.

His father, Johann van Beethoven, worked as a tenor in the same musical establishment and supplemented his income by giving keyboard and violin lessons. In 1767, Johann married Maria Magdalena Keverich, the daughter of Heinrich Keverich, who was head chef at the court of Johann IX Philipp von Walderdorff, Archbishop of Trier. Of the seven children born to Johann van Beethoven, only Ludwig, the second-born, and two younger brothers survived infancy. These were Kaspar Anton Karl van Beethoven (generally known as Karl), born on April 8, 1774, and Nikolaus Johann van Beethoven (generally known as Johann), the youngest, born on October 2, 1776. Ludwig van Beethoven was the eldest surviving child.

The family faced significant challenges due to Johann's increasing alcoholism and depressive tendencies, which led to financial instability and often created an unhappy home environment. His father's chronic alcoholism eventually forced him to retire from court service in 1789. By court order, half of Johann's pension was paid directly to Ludwig to support the family.

1.1.2. Childhood and Early Musical Training

Beethoven's first music teacher was his father, Johann. His musical talent became obvious at a young age. Aware of Leopold Mozart's successes with his son Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and daughter Nannerl, Johann attempted to promote his son as a child prodigy. He famously claimed Beethoven was six years old (he was seven) on the posters for his first public performance in March 1778. The training regime imposed by his father was often harsh and intensive, sometimes reducing the young Beethoven to tears. For instance, Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer, a family friend and keyboard tutor who suffered from insomnia, would occasionally drag young Beethoven from his bed for irregular late-night practice sessions at the keyboard.

Beethoven also received instruction from other local teachers. These included the court organist Gilles van den Eeden (who died in 1782), Franz Rovantini, a relative who instructed him in playing the violin and viola, and the court concertmaster Franz Anton Ries, who also taught him violin.

From 1780 or 1781, Beethoven began studies with his most important teacher in Bonn, Christian Gottlob Neefe. Neefe, a talented composer from Chemnitz, recognized Beethoven's abilities early on and taught him composition. He introduced Beethoven to the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, having him play pieces like The Well-Tempered Clavier. Under Neefe's tutelage, Beethoven's first published work, a set of keyboard variations (WoO 63), appeared in March 1783. He soon began working with Neefe as an assistant organist, initially unpaid in 1782, then as a paid employee of the court chapel from 1784.

1.1.3. Bonn Period and Early Compositions

Beethoven's activities in Bonn included playing organ in the court chapel and later joining the court orchestra as a violist. This role exposed him to a wide range of operas, including works by Mozart, Christoph Willibald Gluck, and Giovanni Paisiello, which broadened his musical horizons.

During this period, Beethoven formed significant relationships that would prove crucial throughout his life. He developed a close bond with the upper-class von Breuning family, giving piano lessons to some of their children. The widowed Helene von Breuning became a "second mother" to Beethoven, teaching him more refined manners and fostering his passion for literature and poetry. The warmth of the von Breuning family provided Beethoven a much-needed retreat from his unhappy home life, which was increasingly dominated by his father's decline into alcoholism. He also met Franz Gerhard Wegeler, a young medical student who became a lifelong friend and later married one of the von Breuning daughters. Another frequent visitor to the von Breuning household was Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, who became a friend and financial supporter. In 1791, Waldstein commissioned Beethoven's first work for the stage, the ballet Musik zu einem Ritterballett (WoO 1).

The period from 1785 to 1790 shows little record of Beethoven's compositional activity. This might be due to the varied, sometimes negative, reception his initial publications received, as well as ongoing family issues. His mother died in July 1787, shortly after his return from a two-week stay in Vienna, where he may have met Mozart. In 1789, a court order redirected half of his father's pension directly to Ludwig for family support due to his father's chronic alcoholism. Ludwig further contributed to the family's income by teaching, which he disliked, and by playing viola in the court orchestra. There, he also befriended Anton Reicha, a composer, flutist, and violinist of about his own age.

From 1790 to 1792, Beethoven composed several works that, though not published at the time, demonstrated a growing range and maturity. Musicologists have identified a theme similar to that of his Third Symphony in a set of variations written in 1791. It was possibly on Neefe's recommendation that Beethoven received his first major commissions: the Literary Society in Bonn commissioned a cantata to mark the recent death of Joseph II (WoO 87), and a further cantata to celebrate the subsequent accession of Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor (WoO 88) may have been commissioned by the Elector. These two "Emperor Cantatas" were not performed during Beethoven's lifetime and were lost until the 1880s, when Johannes Brahms lauded them as "Beethoven through and through," identifying them as examples of the distinctive style that set Beethoven apart from the classical tradition.

Beethoven was likely first introduced to Joseph Haydn in late 1790 when Haydn briefly stopped in Bonn on his way to London. They met again in Bonn in July 1792 during Haydn's return trip from London to Vienna. Arrangements were likely made at that time for Beethoven to study with Haydn. Before Beethoven's departure, Waldstein famously wrote to him: "You are going to Vienna in fulfilment of your long-frustrated wishes... With the help of assiduous labour you shall receive Mozart's spirit from Haydn's hands." Beethoven left Bonn for Vienna in November 1792, amidst rumors of war spilling out of France, and never returned to his hometown.

1.2. First Vienna Period (1792-1802)

Beethoven's initial years in Vienna were a crucial period of intense study and rapid artistic growth, during which he refined his compositional skills, rose as a virtuoso performer, and produced many significant early works.

1.2.1. Studies with Master Composers

Upon arriving in Vienna in November 1792, Beethoven learned that his father had died. He did not immediately focus on establishing himself as a composer but rather devoted himself to study and performance. He sought to master counterpoint under Haydn's direction. However, Haydn, being preoccupied with his successful trips to London, often had little time for Beethoven. Consequently, from 1793, Beethoven secretly sought additional instruction in composition from Johann Schenk, who helped him with counterpoint exercises based on Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum. From 1794, he further studied counterpoint under the renowned theorist Johann Georg Albrechtsberger. Additionally, he received occasional instruction from Antonio Salieri, primarily focusing on Italian vocal composition style; this relationship lasted until at least 1802, and possibly as late as 1809. He also studied violin under Ignaz Schuppanzigh.

When Haydn departed for England in 1794, Beethoven was expected by the Elector to return to Bonn. However, he chose to remain in Vienna, continuing his studies. By this time, it was clear that Bonn would fall to the French, which it did in October 1794, effectively leaving Beethoven without his stipend or the necessity to return. Fortunately, several Viennese noblemen had already recognized his exceptional talent and offered him financial support, including Prince Joseph Franz Lobkowitz, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, and Baron Gottfried van Swieten.

1.2.2. Rise as a Virtuoso Pianist

Assisted by his connections with Haydn and Waldstein, Beethoven began to develop a formidable reputation as a performer and improviser in the aristocratic salons of Vienna. His friend Nikolaus Simrock began publishing his compositions, starting with a set of keyboard variations on a theme by Dittersdorf (WoO 66). By 1793, Beethoven had already established himself as a piano virtuoso in Vienna, but he strategically withheld many works from publication to ensure their eventual appearance would have a greater impact.

In 1795, Beethoven made his public debut in Vienna, featuring a performance of one of his own piano concertos (likely his Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 19, or Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 15) at the Burgtheater on March 29. He concluded his series of performances with a Mozart concerto, for which he had composed a cadenza. Shortly after this debut, Beethoven arranged for the publication of his first compositions to which he assigned an opus number, the three piano trios, Opus 1. These works, dedicated to his patron Prince Lichnowsky, were a significant financial success, generating profits nearly sufficient to cover his living expenses for a year. In 1799, Beethoven participated in a notorious piano 'duel' against the virtuoso Joseph Wölfl at the home of Baron Raimund Wetzlar. The following year, he similarly triumphed against Daniel Steibelt at the salon of Count Moritz von Fries.

1.2.3. Early Major Works and Relationships

The period marked a significant expansion in Beethoven's compositional scope and ambition. His eighth piano sonata, the Pathétique (Op. 13, published in 1799), is described by musicologist Barry Cooper as "surpass[ing] any of his previous compositions, in strength of character, depth of emotion, level of originality, and ingenuity of motivic and tonal manipulation."

Between 1798 and 1800, Beethoven composed his first six string quartets (Op. 18), commissioned by and dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz. He also completed his Septet (Op. 20) in 1799, a work that remained extremely popular throughout his lifetime. With the premieres of his First and Second Symphonies in 1800 and 1803, respectively, Beethoven began to be regarded as one of the most important of a new generation of composers following Haydn and Mozart. His distinctive melodies, musical development, use of modulation and texture, and intense characterization of emotion set him apart from his influences, enhancing the impact of his early published works. For the premiere of his First Symphony, he hired the Burgtheater on April 2, 1800, and staged an extensive program including works by Haydn and Mozart, as well as his Septet, the Symphony, and one of his piano concertos. Though not without difficulties and some criticism, the concert was described by the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung as "the most interesting concert in a long time." By the end of 1800, Beethoven and his music were highly sought after by patrons and publishers alike.

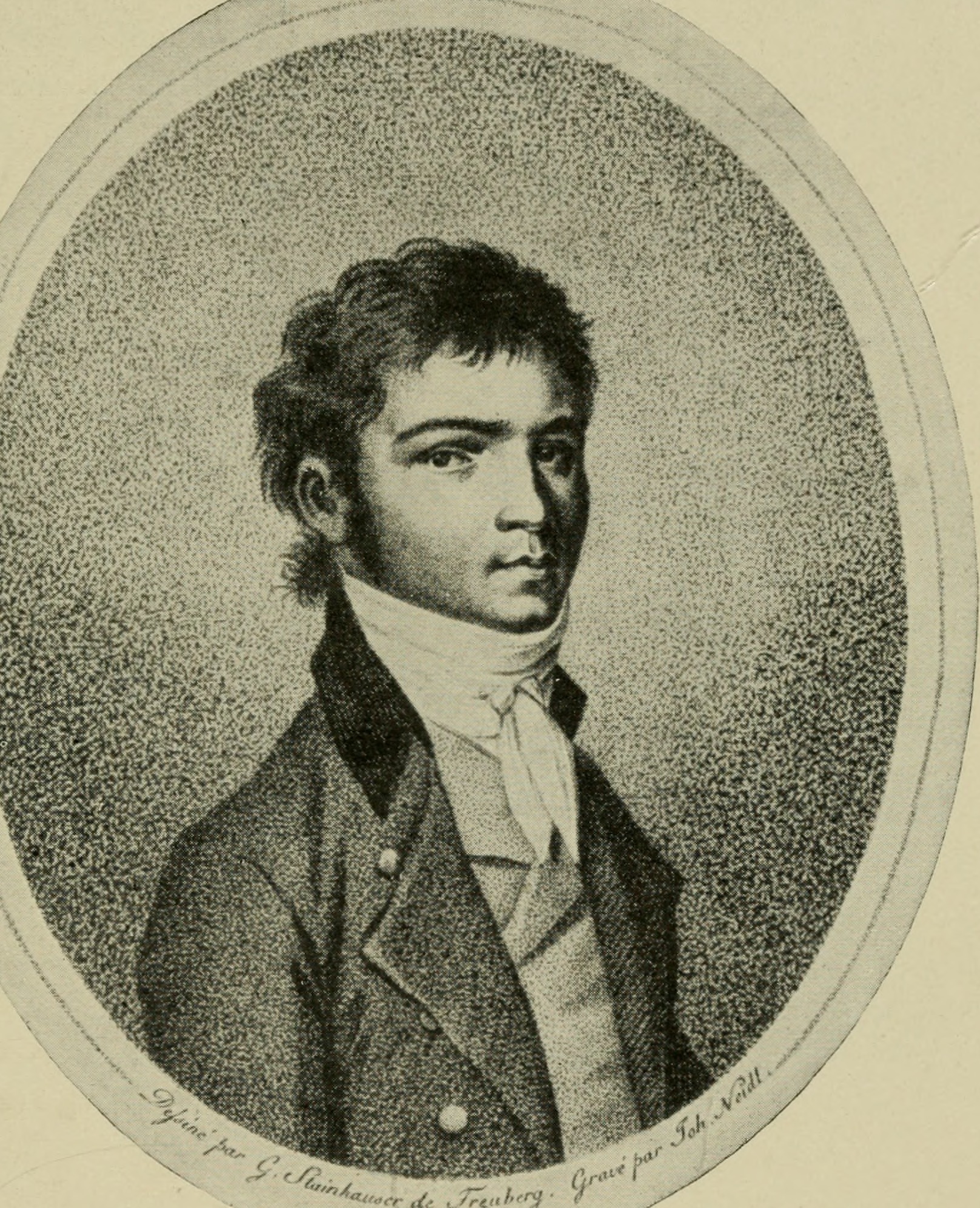

Beethoven's personal life during this time also involved significant romantic interests. In May 1799, while teaching piano to the daughters of Hungarian Countess Anna Brunsvik, he fell in love with the younger daughter, Josephine. Although Josephine later married the elderly Count Joseph Deym in 1800 (a union encouraged by her mother for financial reasons), Beethoven continued to visit their household and developed a passionate correspondence with her after Deym's death in 1804. However, their relationship could not culminate in marriage due to social pressures from the Brunsvik family. In late 1801, Beethoven met the young countess Julie Guicciardi through the Brunsvik family. He expressed his love for Julie in a November 1801 letter to a friend, but the class difference prevented any serious pursuit. He dedicated his 1802 Sonata Op. 27 No. 2, now commonly known as the Moonlight Sonata, to her. Among his other students, Ferdinand Ries studied with him from 1801 to 1805, and Carl Czerny, who later became a renowned pianist and music teacher, studied with Beethoven from 1801 to 1803. Czerny vividly described his initial meeting with Beethoven in 1801: "Beethoven was dressed in a jacket of shaggy dark grey material and matching trousers, and he reminded me immediately of Campe's Robinson Crusoe, whose book I was reading just then. His jet-black hair bristled shaggily around his head. His beard, unshaven for several days, made the lower part of his swarthy face still darker."

In the spring of 1801, Beethoven completed the ballet The Creatures of Prometheus (Op. 43), which received numerous performances in 1801 and 1802. He swiftly published a piano arrangement to capitalize on its early popularity. He finished his Second Symphony in 1802, which premiered a year later in April 1803 at the Theater an der Wien, where Beethoven had been appointed composer in residence. This concert, which also featured the First Symphony, the Third Piano Concerto, and the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, was a financial success, allowing Beethoven to charge three times the cost of a typical concert ticket, despite mixed reviews.

In 1802, Beethoven's brother Kaspar began to assist the composer in handling his affairs, particularly his business dealings with music publishers. Kaspar successfully negotiated higher payments for Beethoven's latest works and also began selling several of Beethoven's earlier unpublished compositions. He encouraged his brother, against Beethoven's preference, to create arrangements and transcriptions of his popular works for other instruments and combinations. Beethoven acceded to these requests, recognizing he was powerless to prevent publishers from hiring others to create similar arrangements of his works.

1.3. Middle ("Heroic") Period (1802-1812)

This critical period in Beethoven's life was profoundly shaped by the onset of his deafness, leading to a period of intense personal struggle and the emergence of his distinctive "heroic" musical style, characterized by grand-scale compositions.

1.3.1. Onset of Deafness and Heiligenstadt Testament

Beethoven confided to the English pianist Charles Neate in 1815 that his hearing loss began in 1798, during a heated quarrel with a singer. As his hearing gradually declined, it was further impeded by a severe form of tinnitus. As early as 1801, he wrote to his friends Wegeler and Carl Amenda, describing his symptoms and the profound difficulties they caused in both professional and social settings, though some close friends were likely already aware of his condition.

The precise cause of Beethoven's deafness remains debated. The most commonly cited theory is otosclerosis, possibly accompanied by degeneration of the auditory nerve. Other possibilities include lead poisoning, with recent analyses of his hair revealing very high lead concentrations, suggesting this as a potential contributing factor. Another theory links it to complications from a case of murine typhus in 1796.

On his doctor's advice, Beethoven moved to the small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt, just outside Vienna, from April to October 1802, in an attempt to come to terms with his condition. There, he wrote the document now known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, an unsent letter to his brothers. This poignant letter records his thoughts of suicide due to his escalating deafness and his ultimate resolution to continue living for and through his art, stating his determination to "seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely." The letter was discovered among his papers after his death.

While Beethoven's hearing loss did not prevent him from composing music, it made performing at concerts-a vital source of income at this stage of his life-increasingly difficult. It also contributed substantially to his social withdrawal. Although it is a common belief that Beethoven became completely deaf, he never did. As late as 1812, he could still hear speech and music normally, according to Czerny. In his final years, he was still able to distinguish low tones and sudden loud sounds. In 1806, on one of his musical sketches, he wrote: "Let your deafness no longer be a secret-even in art."

1.3.2. Development of the "Heroic" Style

Beethoven's return to Vienna from Heiligenstadt was marked by a dramatic shift in his musical style, initiating what is now often designated as his middle or "heroic" period. This era is characterized by many original works composed on a grand scale, reflecting themes of struggle, heroism, and triumph. According to Czerny, Beethoven declared: "I am not satisfied with the work I have done so far. From now on I intend to take a new way."

An early major work exemplifying this new style was the Third Symphony in E-flat, Op. 55, known as the Eroica, composed in 1803-04. The idea of creating a symphony based on the career of Napoleon Bonaparte may have been suggested to Beethoven by General Bernadotte in 1798. Initially sympathetic to the ideal of the heroic revolutionary leader, Beethoven originally titled the symphony "Bonaparte." However, disillusioned by Napoleon declaring himself Emperor in 1804, he famously scratched Napoleon's name from the manuscript's title page, and the symphony was published in 1806 with its present title and the subtitle "to celebrate the memory of a great man." The Eroica was longer and larger in scope than any previous symphony. When it premiered in early 1805, it received a mixed reception; some listeners objected to its length or disliked its structure, while others immediately recognized it as a masterpiece.

Other middle-period works similarly extended the musical language Beethoven had inherited in the same dramatic manner. The Rasumovsky string quartets and the Waldstein and Appassionata piano sonatas share the Third Symphony's heroic spirit. Other significant works of this period include the Fourth through Eighth Symphonies, the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, his only opera Fidelio, and the Violin Concerto. In 1810, the influential writer and composer E. T. A. Hoffmann, in a review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, hailed Beethoven as the greatest of the (what he considered) three Romantic composers (ranking him above Haydn and Mozart). Hoffmann wrote that Beethoven's Fifth Symphony "sets in motion terror, fear, horror, pain, and awakens the infinite yearning that is the essence of romanticism," praising its ability to evoke deep emotional and spiritual experiences.

1.3.3. Patrons, Financial Stability, and Challenges

During this period, Beethoven's income was derived from publishing his works, from performances of them, and crucially, from his patrons. He often gave private performances and provided exclusive copies of commissioned works to his patrons before their public publication. Some of his early patrons, including Lobkowitz and Lichnowsky, provided him with annual stipends in addition to commissioning works and purchasing published scores.

Perhaps his most important aristocratic patron was Archduke Rudolf of Austria, the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II. In 1803 or 1804, Rudolf began studying piano and composition with Beethoven. They developed a close friendship that lasted until 1824. Beethoven dedicated 14 compositions to Rudolf, including such major works as the Archduke Trio Op. 97 (1811) and Missa solemnis Op. 123 (1823).

Beethoven's position at the Theater an der Wien was terminated when the theatre changed management in early 1804, forcing him to move temporarily to the suburbs of Vienna with his friend Stephan von Breuning. This change slowed his work on Leonore (his original title for his opera), his largest work to date. Its premiere, under its revised title Fidelio, in November 1805, was a critical and financial failure, played to nearly empty houses due to the French occupation of the city. Beethoven subsequently began revising the opera.

Despite this setback, Beethoven continued to attract recognition. In 1807, the musician and publisher Muzio Clementi secured the rights to publish his works in England. And Prince Esterházy, Haydn's former patron, commissioned the Mass in C, Op. 86, for his wife's name-day. However, Beethoven could not rely solely on such commissions. A colossal benefit concert he organized in December 1808, widely advertised, included the premieres of the Fifth and Sixth (Pastoral) symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, extracts from the Mass in C, the scena and aria Ah! perfido Op. 65, and the Choral Fantasy op. 80. While attracting a large audience that included Czerny and the young Ignaz Moscheles, the concert was under-rehearsed, marked by many stops and starts, and during the Fantasia, Beethoven was noted shouting at the musicians "badly played, wrong, again!" The financial outcome remains unknown.

In the autumn of 1808, after being rejected for a position at the Royal Theatre in Vienna, Beethoven received an offer from Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother and then King of Westphalia, for a well-paid position as Kapellmeister at the court in Cassel. To persuade him to stay in Vienna, Archduke Rudolf, Prince Kinsky, and Prince Lobkowitz, following appeals from Beethoven's friends, pledged to pay him a pension of 4.00 K FL a year. Rudolf diligently paid his share of the pension on time. Prince Kinsky, however, was immediately called to military duty, did not contribute, and tragically died in November 1812 after falling from his horse. Prince Lobkowitz, who had incurred massive debts building his music room and maintaining his orchestra, went bankrupt in 1811. The Austrian currency also destabilized during this period, significantly devaluing his promised income. To benefit from the agreement, Beethoven eventually had recourse to the law, which in 1815 brought him some recompense.

The imminence of war reaching Vienna itself was keenly felt in early 1809. In April, Beethoven completed his Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73, which musicologist Alfred Einstein described as "the apotheosis of the military concept" in Beethoven's music. Rudolf left the capital with the Imperial family in early May, inspiring Beethoven's piano sonata Les Adieux (Sonata No. 26, Op. 81a), titled by Beethoven in German Das Lebewohl (The Farewell). Its final movement, Das Wiedersehen (The Return), is dated in the manuscript with Rudolf's homecoming date of January 30, 1810. During the French bombardment of Vienna in May, Beethoven took refuge in the cellar of his brother Kaspar's house. The subsequent occupation of Vienna and disruptions to cultural life and Beethoven's publishers, coupled with Beethoven's poor health at the end of 1809, explain his significantly reduced output during this period. Nonetheless, other notable works from this time include his String Quartet No. 10 in E-flat major, Op. 74 (The Harp), and the Piano Sonata No. 24 in F-sharp major, Op. 78, dedicated to Josephine Brunsvik's sister Therese Brunsvik.

1.3.4. Meeting Goethe and the "Immortal Beloved" Controversy

At the end of 1809, Beethoven was commissioned to write incidental music for Goethe's play Egmont. The resulting work (an overture and nine additional entractes and vocal pieces, Op. 84), which appeared in 1810, harmonized well with Beethoven's heroic style and deepened his interest in Goethe. He subsequently set three of Goethe's poems as songs (Op. 83) and learned more about the poet from a mutual acquaintance, Bettina Brentano (who also corresponded with Goethe about Beethoven). Other works of this period reflecting a similar vein were the F minor String Quartet Op. 95, to which Beethoven gave the subtitle Quartetto serioso, and the Op. 97 Piano Trio in B-flat major, known from its dedication to his patron Rudolf, as the Archduke Trio.

In the spring of 1811, Beethoven became seriously ill with headaches and a high fever. His doctor, Johann Malfatti, recommended he take a cure at the spa of Teplitz (now Teplice in the Czech Republic). While there, he composed two more overtures and sets of incidental music for dramas by August von Kotzebue - King Stephen Op. 117 and The Ruins of Athens Op. 113. Advised to visit Teplitz again in 1812, he met Goethe there. Goethe later described Beethoven: "His talent amazed me; unfortunately he is an utterly untamed personality, who is not altogether wrong in holding the world to be detestable, but surely does not make it any more enjoyable... by his attitude." Beethoven, in turn, wrote to his publishers Breitkopf and Härtel, "Goethe delights far too much in the court atmosphere, far more than is becoming in a poet." Despite their differing social perspectives, following their meeting, Beethoven began a setting for choir and orchestra of Goethe's Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage), Op. 112, which he completed in 1815. After its publication in 1822 with a dedication to the poet, Beethoven wrote to him: "The admiration, the love and esteem which already in my youth I cherished for the one and only immortal Goethe have persisted."

While Beethoven was at Teplitz in 1812, he penned a ten-page love letter to his "Immortal Beloved", a letter he never sent to its addressee. The identity of the intended recipient has long been a subject of intense debate among scholars. Musicologist Maynard Solomon has persuasively argued that the intended recipient was Antonie Brentano. Other candidates have included Julie Guicciardi, Therese Malfatti, and Josephine Brunsvik.

All of these women had been regarded by Beethoven as potential soulmates during his first decade in Vienna. Julie Guicciardi, despite flirting with Beethoven, never harbored serious interest in him and married Wenzel Robert von Gallenberg in November 1803. Josephine Brunsvik, after Beethoven's initial infatuation with her, married the elderly Count Joseph Deym. After Deym's death in 1804, Beethoven began to visit Josephine and a passionate correspondence ensued. Initially, he accepted that Josephine could not openly love him due to social constraints, but he continued to pursue her even after she moved to Budapest, finally acknowledging the end of their romantic hope in his last letter to her of 1807: "I thank you for wishing still to appear as if I were not altogether banished from your memory." Therese Malfatti was the niece of Beethoven's doctor, and he proposed to her in 1810, at 40 years old while she was 19. The proposal was rejected. She is now remembered as the possible recipient of the piano bagatelle commonly known as Für Elise.

Antonie (Toni) Brentano (née von Birkenstock), ten years Beethoven's junior, was the wife of Franz Dominicus Brentano, the half-brother of Bettina Brentano, who introduced Beethoven to the family. It appears that Antonie and Beethoven had an affair during 1811-1812. Antonie left Vienna with her husband in late 1812 and never met with (or apparently corresponded with) Beethoven again, although in her later years, she wrote and spoke fondly of him. Some speculate that Beethoven was the father of Antonie's son Karl Josef, though the two never met. After 1812, there are no reports of any romantic liaisons of Beethoven's; however, it is clear from his correspondence of the period and, later, from the conversation books, that he occasionally had sex with prostitutes.

1.4. Late Period (1813-1827)

Beethoven's final years were characterized by intense personal struggles, profoundly innovative musical compositions that pushed artistic boundaries, and a deteriorating physical health, making this a period of both anguish and unparalleled artistic achievement.

1.4.1. Personal Struggles and Legal Battles

In early 1813, Beethoven appears to have entered a difficult emotional period, which led to a significant drop in his compositional output. His personal appearance, which had generally been neat, deteriorated, as did his public manners, notably when dining. Family issues may have contributed to this decline.

In late October 1812, Beethoven had visited his brother Johann with the intention of ending Johann's cohabitation with Therese Obermayer, a woman who already had an illegitimate child. Despite his efforts and appeals to local civic and religious authorities, Johann and Therese married on November 8, a union Beethoven strongly disapproved of.

The illness and eventual death of his brother Kaspar from tuberculosis became an increasing concern. Kaspar had been ill for some time, and in 1813, Beethoven lent him 1.50 K FL for his medical needs, the repayment of which later led to complex legal measures. After Kaspar died on November 15, 1815, Beethoven immediately became embroiled in a protracted legal dispute with Kaspar's widow Johanna over the custody of their son Karl, then nine years old. Beethoven had initially succeeded in having himself named the sole guardian of the boy through Kaspar's will, but a late codicil granted him and Johanna joint guardianship. While Beethoven succeeded in having his nephew removed from Johanna's custody in January 1816 and placed in a private school, he was again preoccupied with legal processes concerning Karl in 1818. During evidence to the court for the nobility, the Landrechte, Beethoven was unable to prove his noble birth. As a consequence, on December 18, 1818, the case was transferred to the civil magistrate of Vienna, where he lost sole guardianship. He regained custody after intensive legal struggles in 1820. In the years that followed, Beethoven frequently interfered in his nephew's life in what Karl perceived as an overbearing and suffocating manner.

1.4.2. Resurgence and Masterpieces

Beethoven was finally motivated to begin significant composition again in June 1813 when news arrived of the French defeat at the Battle of Vitoria by a coalition led by the Duke of Wellington. The inventor Johann Nepomuk Maelzel persuaded him to write a work commemorating the event for his mechanical instrument, the Panharmonicon. Beethoven transcribed this work for orchestra as Wellington's Victory (Op. 91, also known as the Battle Symphony). This programmatic piece, featuring French and British soldiers' songs, a battle scene with artillery effects, and a fugal treatment of "God Save the King", premiered on December 8, along with his Seventh Symphony, Op. 92, at a charity concert for victims of the war. The concert was a great success, leading to its repeat on December 12. The orchestra included several leading musicians who happened to be in Vienna, such as Giacomo Meyerbeer and Domenico Dragonetti. These concerts, repeated in January and February 1814, brought Beethoven more profit than any others in his career, enabling him to buy bank shares that became the most valuable assets in his estate at his death.

Beethoven's renewed popularity led to demands for a revival of Fidelio. In its third revised version, the opera was well received at its July 1814 opening in Vienna and was frequently staged in subsequent years. Beethoven's publisher, Artaria, commissioned the 20-year-old Moscheles to prepare a piano score of the opera, which he inscribed "Finished, with God's help!"-to which Beethoven famously added "O Man, help thyself." That summer, Beethoven composed a piano sonata for the first time in five years, his Sonata in E minor, Opus 90. He was also among many composers who produced patriotic music to entertain the numerous heads of state and diplomats attending the Congress of Vienna that began in November 1814. Works like the cantata Der glorreiche Augenblick (The Glorious Moment) (Op. 136) and similar choral pieces, while broadening Beethoven's popularity, did little to enhance his reputation as a serious composer, according to Maynard Solomon.

In April and May 1814, playing in his Archduke Trio, Beethoven made his last public appearances as a soloist. The composer Louis Spohr noted: "the piano was badly out of tune, which Beethoven minded little, since he did not hear it... there was scarcely anything left of the virtuosity of the artist... I was deeply saddened." From 1814 onward, Beethoven increasingly relied on ear-trumpets designed by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (a number of these are on display at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn) and later, conversation books, for communication as his deafness worsened.

His 1815 compositions included an expressive second setting of the poem An die Hoffnung (Op. 94). Compared to its first setting in 1805 (a gift for Josephine Brunsvik), it was "far more dramatic... The entire spirit is that of an operatic scena." However, his energy seemed to be waning; apart from these works, he wrote the two cello sonatas Op. 102 nos. 1 and 2 and a few minor pieces, and began but abandoned a sixth piano concerto.

Between 1815 and 1819, Beethoven's output dropped again to a level unique in his mature life. He attributed part of this to a lengthy "inflammatory fever" he suffered for over a year starting in October 1816. Solomon suggests it was also a consequence of the ongoing legal problems concerning his nephew Karl and Beethoven's increasing disillusionment with current musical trends. Unsympathetic to developments in German romanticism featuring the supernatural (as in operas by Spohr, Heinrich Marschner, and Carl Maria von Weber), he also "resisted the impending Romantic fragmentation of the cyclic forms of the Classical era into small forms and lyric mood pieces." Instead, he turned towards intensive study of the music of Bach, Handel, and Palestrina. An old connection was renewed in 1817 when Maelzel sought and obtained Beethoven's endorsement for his newly developed metronome. During these years, the few major works he completed include the 1818 Hammerklavier Sonata (Sonata No. 29 in B-flat major, Op. 106) and his settings of poems by Alois Jeitteles, An die ferne Geliebte Op. 98 (1816), which introduced the song cycle into classical repertoire. In 1818, he began musical sketches that eventually formed part of his Ninth Symphony.

By early 1818, Beethoven's health had improved, and his nephew Karl, then age 11, moved in with him in January (though Karl's mother won him back in the courts within a year). By now, Beethoven's hearing had again seriously deteriorated, necessitating that he and his interlocutors write in notebooks to carry out conversations. These 'conversation books' are a rich written resource for his life from this period onward. They contain discussions about music, business, and personal life, and are a valuable source for understanding his contacts, his intentions for performance, and his opinions on music. His household management had also improved somewhat with the help of Nannette Streicher, a proprietor of the Stein piano workshop and a personal friend, who continued to provide support and found him a skilled cook. As a testament to the esteem in which Beethoven was held in England, Thomas Broadwood, the proprietor of the company, presented him with a Broadwood piano in this year, for which Beethoven expressed thanks. However, he was not well enough to undertake a visit to London that year, which had been proposed by the Philharmonic Society.

Despite the time consumed by his ongoing legal struggles over Karl, which involved extensive correspondence and lobbying, two events sparked Beethoven's major composition projects in 1819. The first was the announcement of Archduke Rudolf's promotion to Cardinal-Archbishop of Olomouc (now in the Czech Republic), which prompted the Missa solemnis Op. 123, intended to be ready for Rudolf's installation in Olomouc in March 1820. The other was an invitation by the publisher Antonio Diabelli to 50 Viennese composers, including Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Czerny, and the 8-year-old Franz Liszt, to compose a variation each on a theme he provided. Beethoven was spurred to outdo the competition, and by mid-1819, he had already completed 20 variations of what would become the 33 Diabelli Variations Op. 120. Neither of these monumental works was completed for a few more years. A significant tribute in 1819 was Archduke Rudolf's set of 40 piano variations on a theme written for him by Beethoven (WoO 200), dedicated to the master. Ferdinand Schimon's portrait of Beethoven from this year, which became one of the most familiar images of him for the next century, was described by Schindler as, despite its artistic weaknesses, "in the rendering of that particular look, the majestic forehead... The firmly shut mouth and the chin shaped like a shell,... truer to nature than any other picture." Joseph Karl Stieler also created his own portrait of Beethoven.

Beethoven's determination over the following years to write the Mass for Rudolf was not motivated by devout Catholicism. Although he had been born a Catholic, the form of religion practiced at the Bonn court where he grew up was, in Solomon's words, "a compromise ideology that permitted a relatively peaceful coexistence between the Church and rationalism." Beethoven's Tagebuch (a diary he kept occasionally between 1812 and 1818) shows his interest in a variety of religious philosophies, including those from India, Egypt, and the Orient, and the writings of the Rig-Veda. In a letter to Rudolf in July 1821, Beethoven expressed his belief in a personal God: "God... sees into my innermost heart and knows that as a man I perform most conscientiously and on all occasions the duties which Humanity, God, and Nature enjoin upon me." On one of the sketches for the Missa solemnis, he wrote "Plea for inner and outer peace."

Beethoven's status was confirmed by the series of Concerts spirituels given in Vienna by the choirmaster Franz Xaver Gebauer in the 1819/1820 and 1820/1821 seasons, during which all eight of his symphonies to date, plus the oratorio Christus and the Mass in C, were performed. Beethoven was typically underwhelmed; when a friend mentioned Gebauer in an April 1820 conversation book, Beethoven wrote in reply "Geh! Bauer" (Begone, peasant!).

In 1819, Beethoven was first approached by the publisher Moritz Schlesinger, who, during a visit at Mödling, won over the suspicious composer by procuring for him a plate of roast veal. Consequently, Schlesinger secured the rights to Beethoven's three last piano sonatas and his final quartets. Part of the appeal for Beethoven was that Schlesinger had publishing facilities in Germany and France, and connections in England, which could help overcome problems of copyright piracy. The first of these three sonatas, for which Beethoven contracted with Schlesinger in 1820 at 30 ducats per sonata (further delaying completion of the Mass), was sent to the publisher at the end of that year (the Sonata in E major, Op. 109, dedicated to Maximiliane von Blittersdorf, Antonie Brentano's daughter).

In early 1821, Beethoven was once again in poor health with rheumatism and jaundice. Despite this, he continued work on the remaining piano sonatas he had promised to Schlesinger (the Sonata in A flat major Op. 110 was published in December), and on the Mass. In early 1822, Beethoven sought a reconciliation with his brother Johann, whose marriage in 1812 had met with his disapproval. Johann now became a regular visitor (as witnessed by the conversation books of the period) and began to assist him in his business affairs, including lending him money against ownership of some of his compositions. Beethoven also sought some reconciliation with the mother of his nephew, including supporting her income, although this did not meet with the approval of the contrary Karl. Two commissions at the end of 1822 improved Beethoven's financial prospects. In November, the Philharmonic Society of London offered a commission for a symphony, which he accepted with delight, seeing it as an appropriate home for the Ninth Symphony on which he was working. Also in November, Prince Nikolai Galitzin of Saint Petersburg offered to pay Beethoven's asking price for three string quartets. Beethoven set the price at the high level of 50 ducats per quartet in a letter dictated to his nephew Karl, who was then living with him.

During 1822, Anton Schindler, who in 1840 became one of Beethoven's earliest and most influential (though not always reliable) biographers, began to work as the composer's unpaid secretary. Schindler later claimed he had been a member of Beethoven's circle since 1814, but there is no evidence for this. Cooper suggests that "Beethoven greatly appreciated his assistance, but did not think much of him as a man." It has been suggested by Beethoven's biographer Alexander Wheelock Thayer that, of 400 conversation books, 264 were destroyed (and others were altered) after his death by Schindler, who wished only an idealized biography to survive. The music historian Theodore Albrecht has, however, demonstrated that Thayer's allegations were exaggerated, and that Schindler did not possess as many as 400 conversation books or destroy five-eighths of that number. However, Schindler did insert a number of fraudulent entries that bolstered his own profile and prejudices. Presently, 136 books covering the period 1819-1827 are preserved at the Staatsbibliothek Berlin, with another two at the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn.

1.4.3. Final Public Appearances and Declining Health

The year 1823 saw the completion of three notable works, all of which had occupied Beethoven for some years: the Missa solemnis, the Ninth Symphony, and the Diabelli Variations.

Beethoven at last presented the manuscript of the completed Missa to Rudolph on March 19, 1823 (more than a year after the archduke's enthronement as archbishop). However, he was in no hurry to get it published or performed, as he had formed a notion that he could profitably sell manuscripts of the work to various courts in Germany and Europe for 50 ducats each. One of the few who took up this offer was Louis XVIII of France, who also sent Beethoven a heavy gold medallion. The Symphony and the variations occupied most of the rest of Beethoven's working year. Diabelli hoped to publish both works, but the potential prize of the Mass excited many other publishers, including Schlesinger and Carl Friedrich Peters, to lobby Beethoven for it. In the end, it was acquired by Schotts.

Beethoven had grown critical of the Viennese reception of his works. He told the visiting Johann Friedrich Rochlitz in 1822: "You will hear nothing of me here... Fidelio? They cannot give it, nor do they want to listen to it. The symphonies? They have no time for them. My concertos? Everyone grinds out only the stuff he himself has made. The solo pieces? They went out of fashion long ago, and here fashion is everything. At the most, Schuppanzigh occasionally digs up a quartet." He therefore inquired about premiering the Missa and the Ninth Symphony in Berlin. When his Viennese admirers learned of this, they pleaded with him to arrange local performances. Beethoven was won over, and the symphony was first performed, along with sections of the Missa solemnis, on May 7, 1824, to great acclaim at the Kärntnertortheater. (The first full performance of the Missa solemnis had already been given in St. Petersburg by Galitzin, who had been a subscriber for the manuscript 'preview' that Beethoven had arranged.) Beethoven stood by the conductor Michael Umlauf during the concert, beating time (although Umlauf had warned the singers and orchestra to ignore him), and because of his deafness, was not even aware of the applause that followed until he was turned to witness it. The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung gushed, "inexhaustible genius had shown us a new world," and Carl Czerny wrote that the Symphony "breathes such a fresh, lively, indeed youthful spirit... so much power, innovation, and beauty as ever [came] from the head of this original man, although he certainly sometimes led the old wigs to shake their heads." The concert did not net Beethoven much money, as the expenses of mounting it were very high. A second concert on May 24, in which the producer guaranteed him a minimum fee, was poorly attended; nephew Karl noted that "many people [had] already gone into the country." It was Beethoven's last public concert. Beethoven accused Schindler of either cheating him or mismanaging the ticket receipts; this led to Schindler's temporary replacement as Beethoven's secretary by Karl Holz, the second violinist in the Schuppanzigh Quartet, although by 1826 Beethoven and Schindler reconciled.

Beethoven then turned to writing the string quartets for Galitzin, despite his failing health. The first of these, the quartet in E♭ major, Op. 127, was premiered by the Schuppanzigh Quartet in March 1825. While writing the next, the quartet in A minor, Op. 132, in April 1825, he was struck by a sudden illness. Recuperating in Baden, he included in the quartet its slow movement, to which he gave the title "Holy song of thanks (Heiliger Dankgesang) to the Divinity, from a convalescent, in the Lydian mode." The next quartet to be completed was the Thirteenth, Op. 130, in B♭ major. In six movements, the last, contrapuntal movement proved very difficult for both the performers and the audience at its premiere in March 1826 (again by the Schuppanzigh Quartet). Beethoven was persuaded by the publisher Artaria, for an additional fee, to write a new finale and to issue the last movement as a separate work (the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133). Beethoven's favorite was the last of this series, the quartet in C♯ minor Op. 131, which he rated as his most perfect single work.

Beethoven's relations with his nephew Karl had continued to be stormy; Beethoven's letters to him were demanding and reproachful. In August, Karl, who had been seeing his mother again against Beethoven's wishes, attempted suicide by shooting himself in the head. He survived, and after discharge from hospital, went to recuperate in the village of Gneixendorf with Beethoven and his uncle Johann. In Gneixendorf, Beethoven completed a further quartet (Op. 135 in F major), which he sent to Schlesinger. Under the introductory slow chords in the last movement, Beethoven wrote in the manuscript "Muss es sein?" (Must it be?); the response, over the faster main theme of the movement, is "Es muss sein!" (It must be!). The whole movement is headed Der schwer gefasste Entschluss (The difficult decision). Following this in November, Beethoven completed his final composition, the replacement finale for the Op. 130 quartet. Beethoven at this time was already ill and depressed; he began to quarrel with Johann, insisting that Johann make Karl his heir, in preference to Johann's wife.

2. Health and Death

Beethoven's life was marked by chronic health issues, particularly his progressive deafness, which profoundly impacted his personal and professional life. His death followed a period of severe illness, attracting immense public mourning and scientific inquiry.

2.1. Causes and Progression of Deafness

Beethoven's hearing loss began around 1798 and progressively worsened. It was accompanied by a severe form of tinnitus, making it increasingly difficult for him to perceive musical nuances and engage in conversation. While he was never completely deaf and could still distinguish low tones and sudden loud sounds in his final years, his ability to participate in performances and social interactions was severely hampered.

Several theories have been proposed regarding the cause of his deafness:

- Otosclerosis: This is the most widely accepted medical theory, suggesting that the hardening of the ossicles in the middle ear prevented sound transmission. Symptoms consistent with otosclerosis, such as the ability to perceive high-frequency piano vibrations even when human voices were indistinct, have been cited as evidence. Medical analyses comparing his presumed audiogram with cases of otosclerosis and Paget's disease support this.

- Lead poisoning: Recent scientific analyses of Beethoven's hair, including samples from 2024, have revealed very high concentrations of lead (up to 100 times normal levels). This has led to theories that lead poisoning, possibly from lead acetate used as a sweetener in wine or from lead compounds in medical treatments (e.g., for wound disinfection), could have contributed to his hearing loss and other ailments. However, it's debated whether lead exposure alone could account for the severe extent of his deafness.

- Murine typhus: Complications from a case of typhus contracted in 1796 have also been suggested as a potential cause.

- Other theories: Syphilis, autoimmune disorders, and even his habit of plunging his head into cold water to stay awake have been put forward, though with less supporting evidence.

The progression of his deafness forced him to abandon public performances as a pianist by 1814 and conducting by 1818. Communication became increasingly reliant on written 'conversation books,' through which friends, family, and visitors conversed with him.

2.2. Other Chronic Illnesses

Beyond his deafness, Beethoven suffered from a multitude of chronic illnesses throughout his life, which significantly impacted his daily life and creative output. These included:

- Chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, and colic, which plagued him persistently.

- Fever and inflammatory conditions, often lasting for extended periods, such as the "inflammatory fever" he endured for over a year starting in October 1816.

- Jaundice, which appeared severely in the summer of 1821, signaling advanced liver disease.

- Rheumatism, particularly in early 1821.

- Liver disease: An autopsy after his death revealed severe liver damage, likely alcoholic cirrhosis, a condition possibly exacerbated by his reported heavy alcohol consumption and a newly identified genetic predisposition to liver disease from a 2023 genomic analysis.

- Pneumonia: Contracted in December 1826 during a cold carriage ride from Gneixendorf back to Vienna, this respiratory illness rapidly worsened his already precarious health.

- Dropsy: A build-up of fluid in his limbs and abdomen, a common complication of severe liver disease, led to swelling, coughing, and breathing difficulties in his final months. Several operations were performed to drain this fluid, often with crude methods.

These chronic ailments caused him considerable distress, affecting his mood, social interactions, and sometimes, his ability to compose.

2.3. Final Illness and Passing

Beethoven's final decline began during his return journey to Vienna from Gneixendorf in December 1826. He contracted pneumonia from an open, unheated carriage ride in severe winter weather. He was attended by Andreas Ignaz Wawruch, who observed symptoms including fever, jaundice, and dropsy, with swollen limbs, coughing, and breathing difficulties. Several operations were carried out to tap off the excess fluid from Beethoven's abdomen, which contributed to his increasing weakness.

His nephew Karl, who had been staying by Beethoven's bedside during December, left in early January to join the army at Iglau and did not see his uncle again, though he wrote to him shortly afterwards expressing regret at their separation. Immediately following Karl's departure, Beethoven, realizing the end was near, wrote a will making his nephew his sole heir. Later in January, Beethoven was attended by Dr. Malfatti, whose treatment, recognizing the seriousness of his patient's condition, largely centered on alcohol. As news spread of the severity of Beethoven's condition, many old friends came to visit, including Diabelli, Schuppanzigh, Lichnowsky, Schindler, the composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel, and his pupil Ferdinand Hiller. Many tributes and gifts were also sent, including £100 from the Philharmonic Society in London and a case of expensive wine from Schotts.

During this period, Beethoven was almost completely bedridden despite occasional efforts to rouse himself. On March 24, he famously said to Schindler and others present "Plaudite, amici, comoedia finita est" ("Applaud, friends, the comedy is over"). Later that day, when the wine from Schotts arrived, he whispered, "Pity - too late."

Beethoven died on March 26, 1827, at the age of 56. Only his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner and a "Frau van Beethoven" (possibly his estranged sister-in-law Johanna van Beethoven) were present. According to Hüttenbrenner, at about 5 pm, there was a flash of lightning and a clap of thunder: "Beethoven opened his eyes, lifted his right hand and looked up for several seconds with his fist clenched... not another breath, not a heartbeat more." Many visitors came to the deathbed; some locks of the dead man's hair were retained by Hüttenbrenner and Hiller, among others. An autopsy revealed Beethoven had significant liver damage, which may have been due to his heavy alcohol consumption, and also considerable dilation of the auditory and other related nerves. The actual cause of his death remains debated, with alcoholic cirrhosis, syphilis, infectious hepatitis (supported by recent genetic analysis of his hair), lead poisoning, sarcoidosis, and Whipple's disease all having been proposed.

2.4. Funeral and Burial

Beethoven's funeral procession in Vienna on March 29, 1827, was a massive public event, attended by an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people, reflecting his immense public veneration. Franz Schubert, who would follow Beethoven in death only a year later, and the violinist Joseph Mayseder were among the torchbearers. A funeral oration by the poet Franz Grillparzer (who would also write Schubert's epitaph) was read by the actor Heinrich Anschütz.

Beethoven was initially buried in the Währing cemetery, north-west of Vienna, after a requiem mass at the church of the Holy Trinity (Dreifaltigkeitskirche) in Alserstrasse. His remains were exhumed for study in 1863, where his bones were measured and skull photographed. In 1888, his remains were moved to Vienna's Zentralfriedhof, where they were reinterred in a grave adjacent to that of Schubert, cementing their shared place in musical history.

3. Musical Style and Development

Beethoven's compositional style underwent a profound evolution throughout his career, marked by a constant pursuit of innovation and deeper expression. His unique musical language, characterized by dramatic force, formal expansion, and intense emotional depth, left an indelible mark on the history of music.

3.1. Periodization of Works

As early as 1818, a writer proposed a three-period division of Beethoven's works, a categorization that became a widely adopted convention among his biographers, starting with Schindler, F.-J. Fétis, and Wilhelm von Lenz. While later writers sought to identify sub-periods and acknowledged its limitations-such as generally omitting the early Bonn years and ignoring the differential development of his styles across genres-this three-period classification remains a fundamental framework for understanding Beethoven's artistic trajectory. For instance, while his piano sonatas show a continuous development throughout his life, his symphonies do not all demonstrate linear progress. Of all his compositions, perhaps the string quartets, which neatly group themselves into three periods (Op. 18 in 1801-1802, Opp. 59, 74, and 95 in 1806-1814, and the late quartets from 1824 onward), fit this categorization most precisely. Despite its drawbacks, the notion of discrete stylistic periods remains integral to the study and appreciation of Beethoven's music.

3.1.1. Early Period (Bonn and First Vienna)

Some forty compositions, including ten very early works written by Beethoven up to 1785, survive from his years in Bonn. It has been suggested that Beethoven largely abandoned composition between 1785 and 1790, possibly as a result of negative critical reactions to his first published works. A 1784 review in Johann Nikolaus Forkel's influential Musikalischer Almanack unfavorably compared Beethoven's efforts to those of mere beginners. His three early piano quartets of 1785 (WoO 36), closely modeled on Mozart's violin sonatas, illustrate his dependence on the prevailing music of the period. Beethoven himself did not assign opus numbers to any of his Bonn works, except for those he reworked later in his career, such as some of the songs in his Op. 52 collection (1805) and the Wind Octet (1792), which he reworked in Vienna in 1793 to become his String Quintet, Op. 4. Musicologist Charles Rosen notes that Bonn was somewhat provincial compared to Vienna, and Beethoven was likely unfamiliar with the mature works of Haydn or Mozart, opining that his early style was closer to that of Hummel or Muzio Clementi. Joseph Kerman suggests that at this stage, Beethoven was not particularly distinguished for his works in sonata style, but more for his vocal music; his move to Vienna in 1792 set him on the path to develop the music in the instrumental genres for which he became renowned.

The conventional first period of Beethoven's music began after his arrival in Vienna in 1792. In the initial few years, he seemed to compose less than he had in Bonn, and his Piano Trios, Op. 1, were not published until 1795. From this point onward, he had mastered the "Viennese style," best known from Haydn and Mozart, and was actively making the style his own. His works from 1795 to 1800 are generally larger in scale than the norm, often writing sonatas in four movements instead of three. He typically replaced the traditional minuet and trio with a more energetic scherzo, and his music frequently incorporated dramatic, sometimes even excessive, uses of extreme dynamics and tempi, as well as chromatic harmony. It was this boldness that led Haydn to believe the third trio of Op. 1 was too challenging for an audience to appreciate. During this period, he also explored new directions and gradually expanded the scope and ambition of his work. Some important pieces from the early period include the First and Second symphonies, the set of six Opus 18 string quartets, his first two piano concertos, and the first twenty piano sonatas, including the famous Pathétique sonata, Op. 13.

3.1.2. Middle Period ("Heroic" Style)

Beethoven's middle period began shortly after the profound personal crisis brought on by his recognition of encroaching deafness, as documented in the Heiligenstadt Testament. This period is characterized by large-scale works that express heroism, struggle, and triumph, often on a monumental scale. According to Carl Czerny, Beethoven sought a "new way" in his compositions, exemplified by the bold experiments in his three piano sonatas, Op. 31. His return to Vienna from Heiligenstadt marked a shift in musical style, characterized by grander dimensions and a more dramatic musical language.

The defining features of his "heroic" style include its expansive scale, dramatic expression, and themes of overcoming adversity. Beethoven expanded classical forms such as the sonata and symphony, notably through the lengthening of the coda. He introduced the scherzo in his symphonies from the Second Symphony onward, replacing the more traditional minuet. A hallmark of this period is the thorough development and manipulation of melodic motives and rhythms, as seen in his Fifth Symphony and Seventh Symphony. The "darkness to light" (suffering to triumph) dramatic arch, typically associated with the Fifth Symphony, became a widely influential model for later Romantic composers. He also experimented with programmatic elements, such as in the Sixth Symphony, Pastoral, and linked movements without pause, as in the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies.

Key works from this middle period include six symphonies (Nos. 3-8), the last two piano concertos (Nos. 4 and 5), the Triple Concerto, the Violin Concerto, five string quartets (Nos. 7-11), several piano sonatas (including the Waldstein and Appassionata sonatas), the Kreutzer violin sonata, and his only opera, Fidelio. While this period is often associated with a heroic manner of composing, the use of the term "heroic" has become increasingly controversial in Beethoven scholarship, with some arguing that it does not encompass the full range of expression in all works from this diverse period. For example, while the Third and Fifth Symphonies are easily described as heroic, many others, such as the Sixth Symphony or the Piano Sonata No. 24, are not.

3.1.3. Late Period (Introspection and Innovation)

Beethoven's late period, generally considered to have begun in the decade 1810-1819, is characterized by profound introspection, intense personal expression, and daring formal innovations. This era saw a renewed creative energy after navigating deep personal crises, including the legal battles over his nephew Karl.

During this time, Beethoven embarked on a rigorous study of older music, including works by Palestrina, Johann Sebastian Bach, and George Frideric Handel, whom Beethoven revered as "the greatest composer who ever lived." His late works consequently incorporated complex polyphony, church modes, and various Baroque-era devices. For example, the overture The Consecration of the House (1822) notably included a fugue influenced by Handel's music.

A new, highly personal style emerged, as he returned to the keyboard to compose his first piano sonatas in almost a decade. The works of the late period include the last five piano sonatas (Nos. 28-32), the Diabelli Variations, the last two sonatas for cello and piano, the late string quartets (including the monumental Große Fuge), and two works for very large forces: the Missa solemnis and the Ninth Symphony. These compositions are defined by their intellectual depth, formal audacity, and a deeply individual, often spiritual, expression. The String Quartet, Op. 131, for instance, features seven linked movements, creating a continuous and seamless musical journey. The Ninth Symphony innovatively adds choral forces to the orchestra in its final movement, delivering a powerful message of humanistic ideals and universal brotherhood. Beethoven himself considered his C♯ minor quartet, Op. 131, his "most perfect single work." This "last manner" of Beethoven's compositions represents a culmination of his artistic genius, pushing music beyond conventional boundaries and reflecting his profound artistic and spiritual journey.

3.2. Key Works

Beethoven's extensive oeuvre spans nearly every genre of his time, with numerous compositions standing as cornerstones of the Western classical repertoire.

3.2.1. Symphonies

Beethoven composed nine symphonies, each a distinct and monumental contribution to the genre. While earlier masters like Haydn and Mozart composed far more symphonies, Beethoven's nine are individually unique and foundational.

- The First Symphony in C major, Op. 21, though rooted in classical forms, already hints at his dramatic flair and expanded harmonic language.

- The Second Symphony in D major, Op. 36, shows further development, notably by introducing a scherzo instead of a traditional minuet.

- The Third Symphony in E-flat major, Op. 55, known as the Eroica, marked a revolutionary departure in scale and emotional scope, initially dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte before Beethoven rescinded it. It is famed for its expanded sonata form and heroic themes.

- The Fourth Symphony in B-flat major, Op. 60, is characterized by its grace and lyrical quality, often seen as a respite between its more dramatic neighbors.

- The iconic Fifth Symphony in C minor, Op. 67, often called the Fate Symphony, is renowned for its opening "short-short-short-long" motif and its powerful dramatic narrative from struggle to triumph.

- The Sixth Symphony in F major, Op. 68, the Pastoral, is a programmatic work in five movements, evoking scenes of nature and rural life.

- The Seventh Symphony in A major, Op. 92, is celebrated for its driving rhythms and vibrant energy, which Richard Wagner famously described as the "apotheosis of the dance."

- The Eighth Symphony in F major, Op. 93, is a more compact and cheerful work, often seen as a playful return to classical elegance.

- The monumental Ninth Symphony in D minor, Op. 125, known as the Choral Symphony, is his last and arguably most famous. It is the first major example of a choral symphony, incorporating soloists and a chorus in its final movement to sing Friedrich Schiller's Ode to Joy, a powerful message of human love and brotherhood. This symphony has become a UNESCO cultural heritage and is the official anthem of Europe.

3.2.2. Concertos

Beethoven's contributions to the concerto genre are equally significant, showcasing his virtuosity as a pianist and his innovative approach to the form.

- His five piano concertos range from the early influences of Mozart in the First (Op. 15) and Second (Op. 19) to the grand, expressive style of the Third (Op. 37) and Fourth (Op. 58). The Fifth Piano Concerto in E-flat major, Op. 73, known as the Emperor, stands as one of his most definitive and popular works in the genre.

- The Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, is widely regarded as one of the greatest violin concertos ever written, notable for its lyrical beauty and depth.

- The Triple Concerto in C major, Op. 56, uniquely features a piano, violin, and cello as solo instruments.

3.2.3. Piano Sonatas

Beethoven composed 32 piano sonatas, which collectively represent a comprehensive chronicle of his stylistic evolution and expressive range, often serving as a workshop for his symphonic ideas.

- Early popular works include the dramatic Pathétique (Op. 13) and the introspective Moonlight (Op. 27 No. 2).

- Middle period masterpieces like the virtuosic Waldstein (Op. 53) and the intensely emotional Appassionata (Op. 57) showcase his expanded formal structures and dramatic power.

- His late sonatas, such as the monumental Hammerklavier (Op. 106) and the profound No. 32 (Op. 111), demonstrate his ultimate mastery of counterpoint, innovative variations, and deeply personal expression.

- Other significant piano works include the innovative Diabelli Variations and the popular bagatelle Für Elise.

3.2.4. Chamber Music

Beethoven's chamber music oeuvre is vast and highly influential, particularly his string quartets, which are considered a pinnacle of the genre.

- His 16 string quartets range from the six early Op. 18 quartets, which solidified his command of the classical style, to the groundbreaking middle-period quartets like the Rasumovsky quartets, the Harp (Op. 74), and the Serioso (Op. 95). The late quartets (Nos. 12-16), including the formidable Grosse Fuge (Op. 133) and the deeply philosophical Op. 131, are considered some of his most profound and innovative works, pushing the boundaries of the form.

- His 10 violin sonatas include the lyrical Spring (Op. 24) and the fiery Kreutzer (Op. 47), which is almost a concerto for violin and piano.

- The 5 cello sonatas, particularly the two late ones (Op. 102), are noted for their innovative forms and emotional depth.

- His piano trios, such as the dramatic Ghost (Op. 70 No. 1) and the majestic Archduke (Op. 97), are staples of the chamber repertoire.

- Other notable chamber works include the Septet in E-flat major, Op. 20, which was highly popular during his lifetime, and the Horn Sonata in F major, Op. 17.

3.2.5. Operas, Oratorios, and Choral Works

Beethoven's vocal compositions, though fewer in number than his instrumental works, are of immense significance, reflecting his humanistic ideals.

- His only opera, Fidelio (Op. 72), is a testament to his belief in freedom and justice, undergoing several revisions as he strove to perfect its message and dramatic impact. It tells the story of a wife's heroic efforts to rescue her political prisoner husband.

- His major choral works include the monumental Missa solemnis in D major, Op. 123, a work of profound spiritual depth and massive scale, regarded as one of the most important religious vocal works in Western music. He also composed the earlier Mass in C major, Op. 86.

- The oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, Op. 85, is another significant vocal work.

- The Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. 80, for piano, chorus, and orchestra, features a main theme that foreshadows the Ode to Joy from his Ninth Symphony.

- His incidental music for plays, such as Egmont (Op. 84), The Ruins of Athens (Op. 113), and King Stephen (Op. 117), demonstrates his dramatic flair in vocal and orchestral settings.

- The ballet The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43, was an early success.

- His song cycle An die ferne Geliebte (Op. 98) is a pioneering work in the genre.

4. Philosophy and Artistic Views

Beethoven's intellectual framework was deeply rooted in Enlightenment thought, shaping his profound philosophical and political convictions, and consequently, his revolutionary beliefs about the nature and purpose of music itself.

4.1. Philosophical Influences and Religious Beliefs

Beethoven's intellectual curiosity led him to engage with the ideas of prominent Enlightenment thinkers, including Immanuel Kant, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich Schiller. He was said to have planned to attend Kant's lectures, a testament to his intellectual aspirations. Beyond Western philosophy, his Tagebuch (a personal diary kept intermittently between 1812 and 1818) reveals his interest in diverse religious philosophies, including those from India, Egypt, and the Orient, and he notably read the writings of the Rig-Veda.

Though born a Catholic, Beethoven's religious views were far from orthodox. The form of religion practiced at the Bonn court where he grew up was, as described by Maynard Solomon, "a compromise ideology that permitted a relatively peaceful coexistence between the Church and rationalism." His personal faith inclined towards a pantheistic and highly individualistic belief in a personal God. In a letter to Archduke Rudolf in July 1821, he affirmed his conviction: "God... sees into my innermost heart and knows that as a man I perform most conscientiously and on all occasions the duties which Humanity, God, and Nature enjoin upon me." This deeply personal spirituality found expression in his compositions, as evidenced by his inscription on a sketch for the Missa solemnis: "Plea for inner and outer peace." His unfinished Symphony No. 10 was reportedly intended to fuse Christian and Greek philosophical worlds, reflecting his broad intellectual scope.

4.2. Political Stance and Liberalism

Beethoven was a staunch liberal and held progressive political views, openly expressing his sympathy for the ideals of the French Revolution, particularly its emphasis on liberty, equality, and fraternity. His only opera, Fidelio, powerfully embodies these ideals, with its narrative of a heroic woman striving for freedom and justice against political tyranny.

His relationship with aristocratic patronage was often strained, as he vehemently rejected the subservient role traditionally expected of musicians. He famously declared to Prince Lichnowsky in 1812: "Prince, what you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am by myself. There have been and will be thousands of princes; there is only one Beethoven!" This assertion reflects his profound pride in his self-made social status and his conviction that artistic genius transcended inherited rank. He often found aristocratic formalities tedious, once complaining to Franz Wegeler about the obligation to return home at 3:30 PM daily to dress and shave for dinner, stating, "I'm sick of it!"

Beethoven's commitment to liberal ideals led to clashes with the conservative Metternich regime in Vienna. His open political leanings made him a suspect figure, sometimes considered an anti-establishment individual by the authorities. The common narrative of "Beethoven the eccentric" is sometimes viewed as a potential byproduct of regime-sponsored disinformation, designed to discredit artists who did not conform. Some scholars even speculate that his extensive use of 'conversation books' in his later years, ostensibly due to deafness, might have also served as a means to circumvent surveillance, possibly containing coded messages. His famous encounter with Goethe in Teplitz exemplifies his independent spirit: while Goethe deferentially moved aside for an imperial procession, Beethoven marched proudly through it, receiving the greetings of the royals, then criticized Goethe for showing "too much respect" to such figures. This firm stance on freedom and self-determination, while earning him admiration from many, also led to a reduction in major commissions under the Metternich government.

Beethoven was also well-read in astronomy, indicating a broader intellectual engagement beyond music. Despite having no formal education beyond his time as an auditing student at the University of Bonn and education from the von Breuning family, he was considered a highly cultivated individual for his era.

4.3. Musical Aesthetics

Beethoven's musical aesthetics articulated a vision of music as a profound art form, far beyond mere entertainment, capable of expressing deep humanistic ideals and the pursuit of universal freedom. He believed music could serve as a vehicle for the human spirit's journey through struggle to triumph, a theme powerfully embodied in works like his Fifth Symphony.

He was relentless in his pursuit of formal and technical innovations to achieve his artistic purpose. While he operated within the existing classical forms (symphony, concerto, sonata, variation), he dramatically expanded their scope and expressive potential. He pushed the boundaries of musical language through:

- Expanded Forms: He enlarged the scale of movements, especially the coda, and experimented with movement order (e.g., placing the scherzo before the slow movement in some symphonies).

- Motivic Development: His systematic and exhaustive development of short melodic motifs and rhythmic cells created unprecedented unity and dramatic tension within his works.

- Orchestration and Dynamics: He employed a bolder and richer orchestration, pushing instruments to their limits and utilizing extreme dynamics and sudden contrasts for heightened emotional impact. He also experimented with sounds, famously incorporating artillery effects in Wellington's Victory and vocal elements into the symphony in his Ninth.

- Technical Challenge: His compositions often presented formidable technical challenges for performers, pushing the physical limits of both the musician and the instrument itself (e.g., the extended range required for his piano sonatas).

- Tempo Markings: He was among the first to frequently use metronome markings and preferred to use his native German for tempo indications, rather than the traditional Italian, though this practice was not widely adopted by contemporaries and he himself reverted to Italian later.

Despite his close connection to the burgeoning Romantic movement and praise from figures like E.T.A. Hoffmann who championed him as a Romantic composer, Beethoven maintained a critical distance from what he perceived as the excessive sentimentality and formal looseness prevalent in some contemporary Romantic art. He drew inspiration from the formal rigor and contrapuntal mastery of older composers like Bach and Handel, as well as the classical balance of Mozart. In literature, his preferences lay with the profound works of Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller, whose humanistic ideals resonated deeply with his own artistic vision.

The question of whether Beethoven was an "avant-garde" composer remains a topic of debate among musicologists. Some argue he was not, as he did not invent entirely new genres but rather expanded existing ones. However, his profound influence on subsequent composers, who continued to build upon his innovations in form, harmony, and expression, is undeniable, marking a revolutionary shift in music history.

5. Personal Life and Character

Beethoven's personal life was as complex and contradictory as his music, revealing a character marked by both profound sensitivity and fierce independence, often navigating challenging relationships and personal struggles.

5.1. Appearance and Habits

Beethoven was of average height for his time, around 65 in (165 cm) (or 66 in (168 cm) according to Schindler), with a muscular and sturdy build. Accounts of his physical appearance vary; some described him as "short, ugly, red pock-marked, clumsy man" (von Bernhard), while others noted his "expressive, lively eyes" that made a strong impression despite any facial imperfections. He had a dark complexion and bore the scars of smallpox. His jet-black hair was often described as bristling shaggily around his head, giving him a "Robinson Crusoe"-like appearance, as observed by his student Carl Czerny.

He was notoriously indifferent to his physical appearance and clothing, particularly as he grew older. While he dressed more meticulously in his youth, he later became unconcerned with fashion, sometimes appearing disheveled. This led to an unusual incident where he was once mistaken for a vagrant and arrested by the police while walking without a hat, prompting an apology from the Mayor of Vienna.