1. Life

Robert Schumann's life was marked by a deep engagement with both music and literature, personal struggles, and profound relationships that shaped his artistic journey.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Robert Schumann was born on 8 June 1810 in Zwickau, in the Kingdom of Saxony (present-day Saxony, Germany), as the fifth and last child of August Schumann and Johanna Christiane. August Schumann was a notable citizen, bookseller, lexicographer, author of chivalric romances, and publisher, who earned significant income from his German translations of writers such as Cervantes, Walter Scott, and Lord Byron. Robert, his favorite child, spent many hours exploring literary classics in his father's extensive collection. Between the ages of three and five and a half, he was intermittently placed with foster parents due to his mother contracting typhus.

At age six, Schumann began attending a private preparatory school for four years. When he was seven, he started studying general music and piano with the local organist, Johann Gottfried Kuntsch. He also received cello and flute lessons from Carl Gottlieb Meissner, one of the municipal musicians. Throughout his childhood and youth, his love for music and literature developed in parallel, with poems and dramatic works produced alongside small-scale compositions, primarily piano pieces and songs. Although not a child prodigy like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart or Felix Mendelssohn, his talent as a pianist was evident early on. A biographical sketch from 1850 in the Allgemeine musikalische ZeitungGerman (Universal Musical Journal) noted his special talent for portraying feelings and characteristic traits in melody: "Indeed, he could sketch the different dispositions of his intimate friends by certain figures and passages on the piano so exactly and comically that everyone burst into loud laughter at the accuracy of the portrait."

From 1820, Schumann attended the Zwickau Lyceum, a local high school of about two hundred boys, until he was eighteen. He pursued a traditional curriculum while reading extensively. Among his early enthusiasms were Schiller and Jean Paul, the latter remaining his favorite author and profoundly influencing his creativity with his sensibility and vein of fantasy. Musically, Schumann became familiar with the works of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and contemporary composers like Carl Maria von Weber, with whom August Schumann unsuccessfully tried to arrange studies for Robert. August, though not particularly musical, encouraged his son's interest, buying him a Streicher grand piano and organizing trips to Leipzig for a performance of The Magic Flute and to Carlsbad to hear the celebrated pianist Ignaz Moscheles. This experience deeply impressed Schumann and motivated him to become a pianist.

1.2. University and Early Career

August Schumann died in 1826. His widow, Johanna, was less supportive of a musical career for her son and persuaded him to study law. After his final examinations at the Lyceum in March 1828, he entered Leipzig University. Accounts differ regarding his diligence as a law student; his roommate claimed he never attended a lecture, while Schumann himself wrote of enjoying jurisprudence. Nonetheless, reading and playing the piano occupied much of his time, and he developed expensive tastes. During this period, he also engaged in several romantic relationships, including with Liddy Hemper, Nanni Patsch, and Agnes Carus, often concurrently. Musically, he discovered the works of Franz Schubert, whose death in November 1828 deeply saddened him. The leading piano teacher in Leipzig, Friedrich Wieck, recognized Schumann's talent and accepted him as a pupil.

After a year in Leipzig, Schumann convinced his mother to let him transfer to the University of Heidelberg, which offered courses in Roman, ecclesiastical, and international law, and where his close friend Eduard Röller was studying. After matriculating on 30 July 1829, he traveled in Switzerland and Italy from late August to late October. He was captivated by Rossini's operas and the bel cantoItalian of soprano Giuditta Pasta, writing to Wieck that "one can have no notion of Italian music without hearing it under Italian skies." Another significant influence was hearing violin virtuoso Niccolò Paganini play in Frankfurt in April 1830. A biographer noted that "The easy-going discipline at Heidelberg University helped the world to lose a bad lawyer and to gain a great musician." Finally deciding on music over law, he wrote to his mother on 30 July 1830, stating: "My entire life has been a twenty-year struggle between poetry and prose, or call it music and law." He persuaded her to seek Wieck's objective assessment of his musical potential. Wieck's verdict was that with hard work, Schumann could become a leading pianist within three years, and a six-month trial period was agreed upon.

Later in 1830, Schumann published his first work, the Abegg Variations, Op. 1, a set of piano variations based on a musical cryptogram of the name "Abegg." The use of such cryptograms became a recurrent characteristic in his later music. In 1831, he began harmony and counterpoint lessons with Heinrich Dorn, musical director of the Saxon court theatre. In 1832, he published his Op. 2, PapillonsFrench (Papillons), a programmatic piece depicting twin brothers-one a poetic dreamer, the other a worldly realist-both in love with the same woman at a masked ball. Schumann by then regarded himself as having two distinct sides to his personality and art, dubbing his introspective self "Eusebius" and his impetuous alter ego "Florestan." Reviewing an early work of Frédéric Chopin in 1831, he wrote, "Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!"

Schumann's pianistic ambitions were thwarted by a progressive paralysis in at least one finger of his right hand. The early symptoms appeared while he was still a student at Heidelberg, and the exact cause remains uncertain. Theories include damage from a chiroplast (a finger-stretching device), mercury poisoning as a side effect of syphilis treatment (later discounted by neurologists), or focal dystonia. He tried various treatments without success. By 1832, he recognized that a career as a virtuoso pianist was impossible and shifted his main focus to composition. He completed further sets of small piano pieces and the first movement of a symphony, though it was never completed.

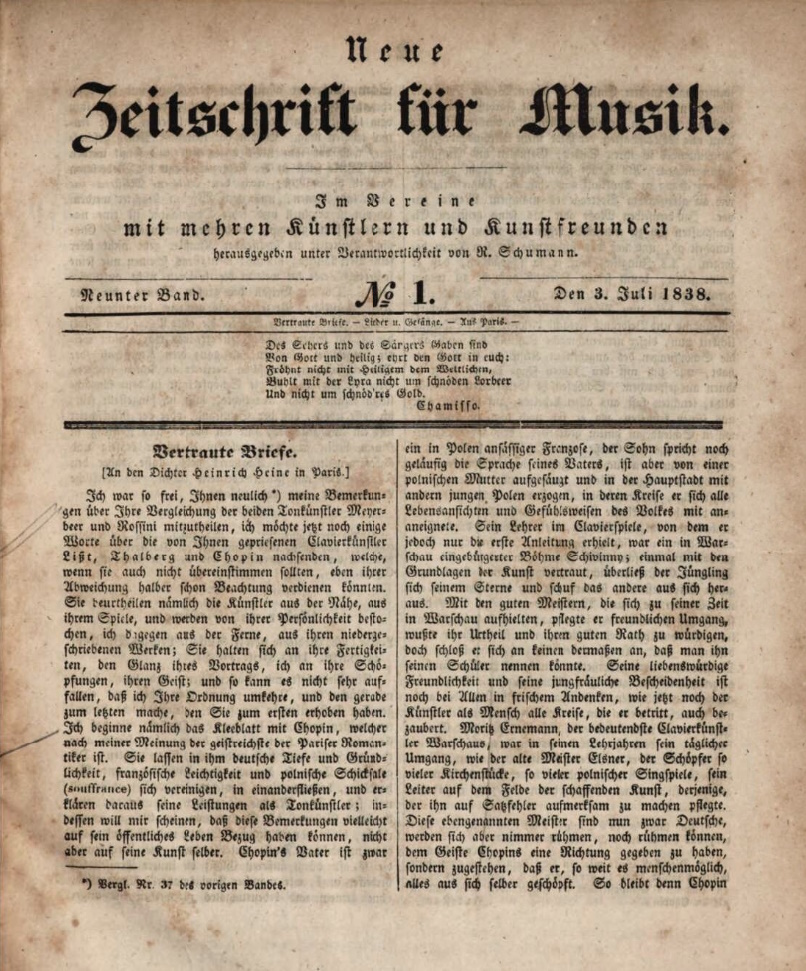

An additional activity was journalism. From March 1834, he joined Wieck and others on the editorial board of a new music magazine, Neue Leipziger Zeitschrift für MusikGerman, which was reconstituted under his sole editorship in January 1835 as the Neue Zeitschrift für MusikGerman (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik). This journal took a "thoughtful and progressive line on the new music of the day." Among the contributors were Schumann's friends and colleagues, who wrote under pen names. He included them in his DavidsbündlerGerman (Davidsbündler)-a band of fighters for musical truth, named after the Biblical hero who fought against the Philistines-a product of the composer's imagination blurring the boundaries of imagination and reality.

During 1835, Schumann met three musicians he greatly respected: Felix Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Moscheles. Mendelssohn particularly influenced his compositions. Early in 1835, he completed Carnaval, Op. 9, and the Symphonic Studies, Op. 13. These works stemmed from his romantic relationship with Ernestine von Fricken, a fellow pupil of Wieck. The musical themes of Carnaval derive from the name of her hometown, Aš (Asch), using the notes A-E♭-C-B (A-S-C-H in German notation). The Symphonic Studies are based on a melody by Ernestine's father, Baron von Fricken. Schumann and Ernestine became secretly engaged, but the engagement ended as Schumann found her personality less interesting and discovered her illegitimate, impecunious background.

1.3. Marriage and Family Life

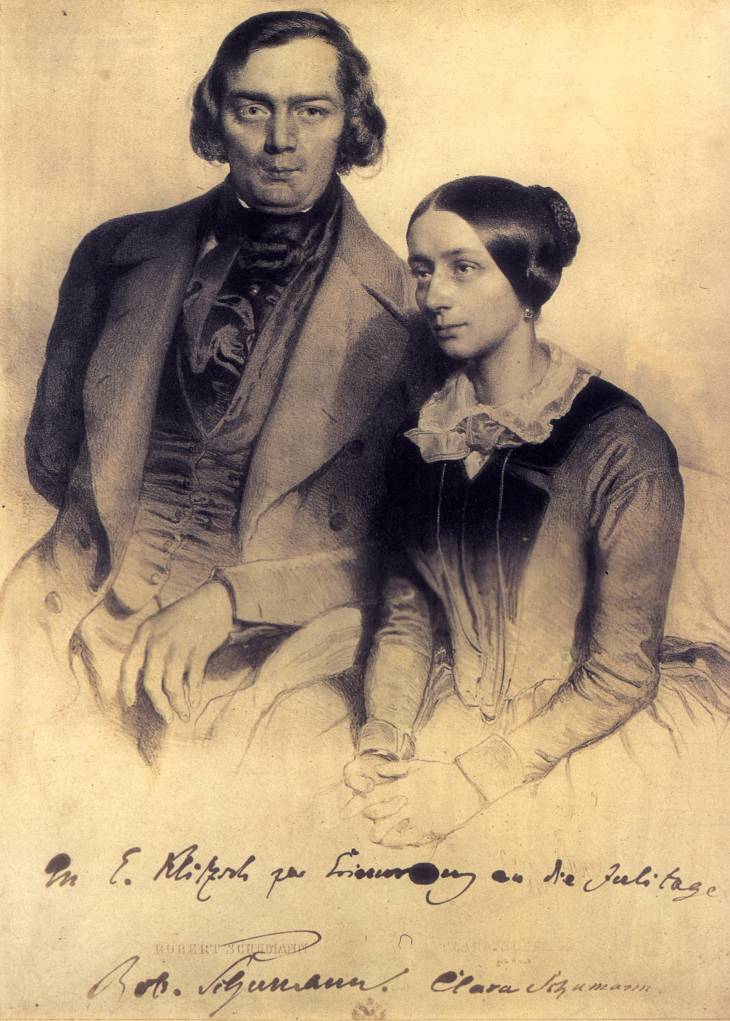

Schumann felt a growing attraction to Wieck's daughter, the sixteen-year-old Clara. She was her father's star pupil, a piano virtuoso emotionally mature beyond her years, with a developing reputation. Her concerto debut at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 9 November 1835, with Mendelssohn conducting, cemented her future as a great pianist. Schumann, who had admired her career since she was nine, fell in love with her, and their feelings were reciprocated in January 1836.

Schumann expected Wieck to welcome the proposed marriage, but he was mistaken. Wieck vehemently opposed it, fearing Schumann's inability to provide for his daughter, that she would have to abandon her career, and that she would be legally required to relinquish her inheritance. This led to a series of acrimonious legal actions over the next four years. Wieck subjected Clara to strict surveillance, censoring her letters and forbidding her from going out alone, and publicly slandered Schumann with false accusations of financial instability and alcoholism. He even attempted to enlist Ernestine von Fricken and Clara's vocal teacher, Carl Banck, in his schemes to disrupt the relationship. Despite the immense pressure, Clara and Robert maintained secret correspondence and continued their relationship through music, with Clara performing Schumann's works in her concerts.

The legal battle culminated in a court ruling on 12 August 1840, permitting Schumann and Clara to marry without her father's consent. They married on 12 September 1840, the day before Clara's twenty-first birthday, in a church near Leipzig. The marriage provided Schumann with "the emotional and domestic stability on which his subsequent achievements were founded." Clara, an internationally renowned pianist, made sacrifices for their marriage, as her career was frequently interrupted by the births of their eight children: Marie (1841), Elise (1843), Julie (1845), Emil (1846, died 1847), Ludwig (1848), Ferdinand (1849), Eugenie (1851), and Felix (1854). She inspired Schumann to extend his compositional range beyond solo piano works.

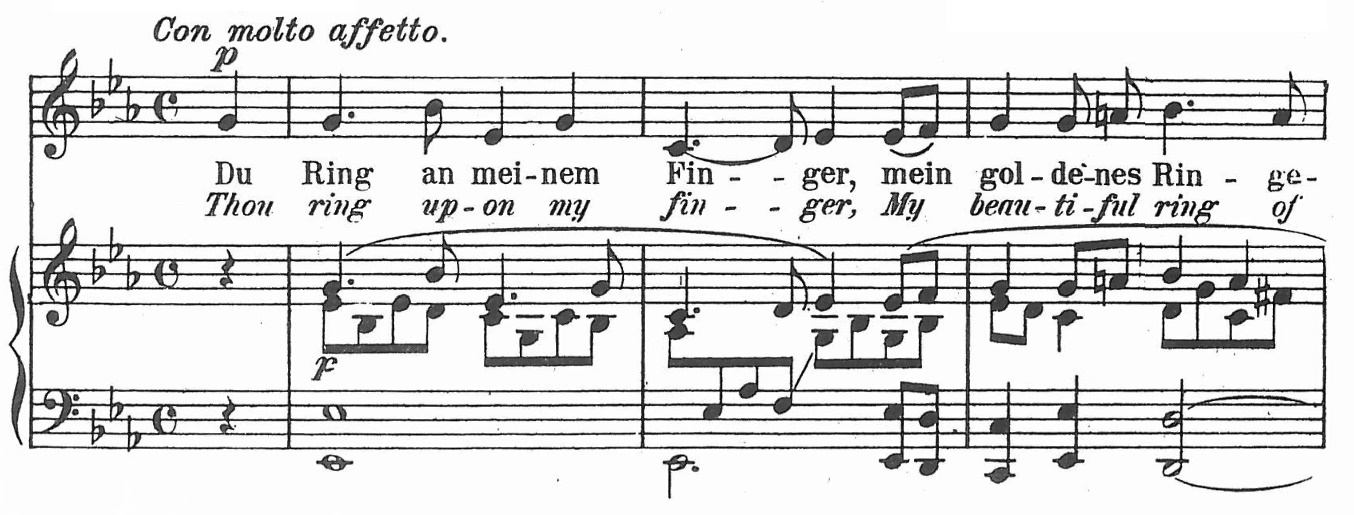

During 1840, Schumann focused on song, producing more than half of his total output of Lieder, including the cycles MyrthenGerman (Myrthen, "Myrtles," a wedding present for Clara), Frauenliebe und LebenGerman (Frauen-Liebe und Leben, "Woman's Love and Life"), DichterliebeGerman (Dichterliebe, "Poet's Love"), and settings of words by Joseph von Eichendorff, Heinrich Heine, and others. This year is often referred to as his LiederjahrGerman (year of song).

In 1841, Schumann turned to orchestral music, with his First Symphony, The Spring, premiered by Mendelssohn on 31 March. His next orchestral works included the Overture, Scherzo and Finale, the Phantasie for piano and orchestra (later the first movement of the Piano Concerto), and a new symphony (published as the Fourth, in D minor). In 1842, he concentrated on chamber music, studying works by Haydn and Mozart, and composing three string quartets, a Piano Quintet, and a Piano Quartet.

In early 1843, Schumann experienced a severe mental crisis, which was not his first but the worst to date. This condition may have been congenital, affecting his father and sister. Later that year, he recovered and completed the secular oratorio, Das Paradies und die PeriGerman (Das Paradies und die Peri, Paradise and the Peri), based on a poem by Thomas Moore. Its premiere on 4 December was a success, bringing him international attention. In 1843, Mendelssohn invited him to teach piano and composition at the new Leipzig Conservatory, and Wieck sought reconciliation. Schumann accepted both, though his relationship with his father-in-law remained polite rather than close.

In 1844, Clara embarked on a concert tour of Russia, joined by Robert. They met leading Russian musicians like Mikhail Glinka and Anton Rubinstein and were impressed by Saint Petersburg and Moscow. Though an artistic and financial success, the tour was arduous, leaving Schumann physically and mentally drained. Upon their return to Leipzig in May, he sold the Neue Zeitschrift and, in December, the family moved to Dresden. Schumann hoped Dresden, with its thriving opera house, would allow him to pursue operatic composition. His health remained poor, with complaints of insomnia, weakness, auditory disturbances, tremors, and various phobias.

From early 1845, Schumann's health improved. He and Clara studied counterpoint, and he completed his Piano Concerto, Op. 54, by adding a slow movement and finale to his 1841 Phantasie. The following year, he worked on his Second Symphony, Op. 61, progress on which was interrupted by further illness. He then began his only opera, Genoveva, completed in August 1848.

A concert tour to Vienna, Berlin, and other cities from November 1846 to February 1847 was mixed. Vienna was largely unsuccessful, but Berlin's performance of Das Paradies und die Peri was well-received. The tour allowed Schumann to see numerous operatic productions, reinforcing his desire to write operas. The Schumanns faced personal tragedies in 1847, including the death of their first son, Emil, and the deaths of Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn. Two more sons, Ludwig and Ferdinand, were born in 1848 and 1849.

1.4. Mental Health and Final Years

Genoveva, a four-act opera based on the medieval legend of Genevieve of Brabant, premiered in Leipzig in June 1850, conducted by the composer. Despite two immediate repeat performances, it was not the success Schumann hoped for, criticized for being too much like a series of Lieder and not dramatic enough. Franz Liszt revived it in Weimar in 1855, the only other production during Schumann's lifetime. It has remained largely outside the standard operatic repertoire.

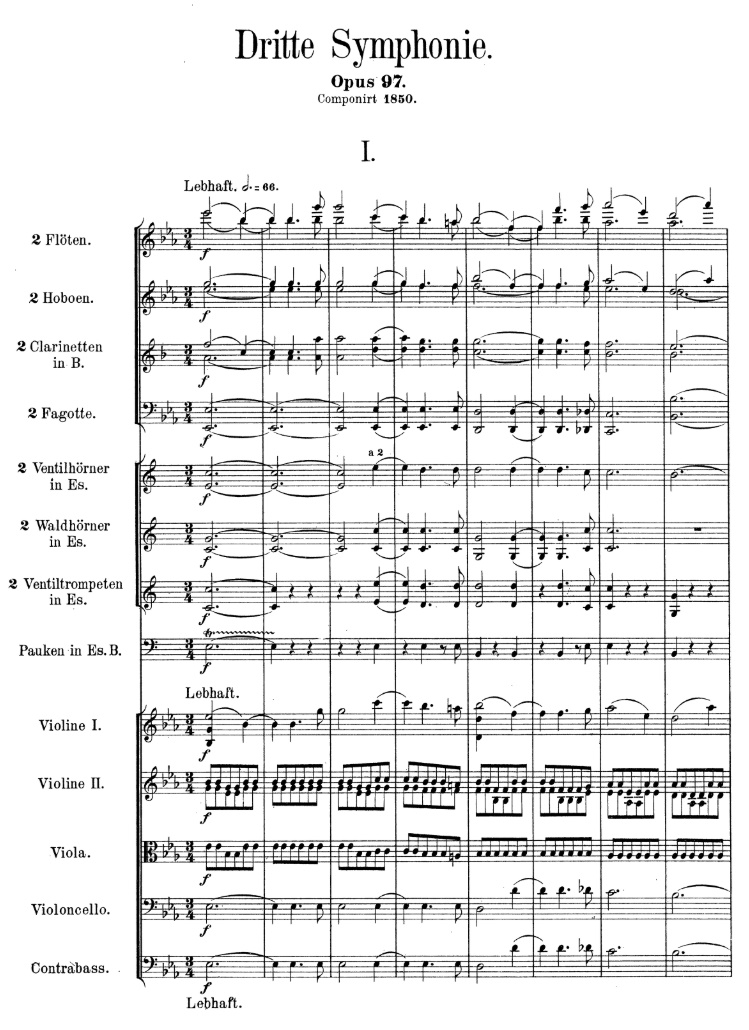

Seeking financial security for his large family, Schumann accepted a post as director of music in Düsseldorf in April 1850. However, his diffidence in social situations and increasing mental instability led to a deterioration of relations with local musicians, culminating in his resignation in 1853. In 1853, as his mental state deteriorated, Schumann reportedly engaged in spiritualism and séances with his daughter Elise, finding the phenomena 'truly wondrous'. Despite these challenges, Schumann composed two substantial late works in 1850: the Cello Concerto (Op. 129) and the Third (Rhenish) Symphony (Op. 97). He continued to compose prolifically, reworking earlier pieces like the D minor symphony from 1841, published as his Fourth Symphony (1851), and the 1835 Symphonic Studies (1852).

In 1853, the twenty-year-old Johannes Brahms visited Schumann with a letter of introduction from the violinist Joseph Joachim. Brahms played his recently composed piano sonatas for Schumann, who was so impressed that he wrote his last article for the Neue Zeitschrift für MusikGerman, titled "Neue BahnenGerman" (New Paths), extolling Brahms as a musician destined "to give expression to his times in ideal fashion." Brahms became a crucial source of support for Clara during the difficult years that followed.

In early 1854, Schumann's health drastically deteriorated. On 27 February, he attempted suicide by throwing himself into the Rhine River but was rescued by fishermen. At his own request, he was admitted to a private sanatorium at Endenich, near Bonn, on 4 March. He remained there for over two years, gradually worsening, with intermittent periods of lucidity during which he wrote and received letters and sometimes attempted composition. The sanatorium director restricted direct contact between patients and relatives to avoid distress and improve recovery chances. Friends, including Brahms and Joachim, were permitted to visit, but Clara did not see her husband until nearly two and a half years into his confinement, just two days before his death.

Schumann died at the sanatorium at age 46 on 29 July 1856. The official cause of death was recorded as pneumonia. However, as with his earlier hand ailment, the cause of his decline and death has been the subject of much conjecture. Theories include tertiary syphilis (which was widely treated with mercury at the time, potentially causing mercury poisoning), congenital bipolar disorder, or brain atrophy. Some scholars suggest the syphilis diagnosis was concealed to spare Clara's feelings. Despite these debates, his final years were marked by profound mental suffering.

His last words were reportedly, "meine... ich kenne..." ("my... I know..."). He was buried two days later in Bonn. Brahms, Joachim, and Dietrich carried the coffin. Clara, who had kept the funeral private, was joined only by a few close friends and members of the Concordia Gesellschaft orchestra, who had performed a serenade upon the Schumanns' arrival in Düsseldorf six years prior.

2. Music Career

Schumann's music career spanned various roles as a composer, pianist, and influential music critic, evolving significantly across different periods and genres.

2.1. Overview and Evolution

Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians (2001) describes Schumann as a "great German composer of surpassing imaginative power whose music expressed the deepest spirit of the Romantic era," concluding that he "was a master of lyric expression and dramatic power, perhaps best revealed in his outstanding piano music and songs." Schumann believed in the identical aesthetics of all arts, aiming for a conception of art where the poetic was paramount. According to musicologist Carl Dahlhaus, for Schumann, "music was supposed to turn into a tone poem, to rise above the realm of the trivial, of tonal mechanics, by means of its spirituality and soulfulness."

In the late 19th and most of the 20th centuries, it was widely held that Schumann's later music (from the mid-1840s onwards) lacked the inspiration of his earlier works, attributed either to his declining health or an increasingly orthodox compositional approach that stifled his Romantic spontaneity. Composer Felix Draeseke famously commented, "Schumann started as a genius and ended as a talent." However, in recent times, his later works have been viewed more favorably, partly due to more frequent performances and recordings, benefiting from historically informed performance practices applied to mid-19th-century music.

Schumann's creative output can be broadly divided into distinct periods, often characterized by a focus on specific genres. This tendency to concentrate intensely on one genre before moving to another is unique among composers. Scholars have noted that his work often appears in groups or cycles, reflecting a "cyclical temperament" where creative impulses would emerge in different fields. Despite this, recent research into his unpublished sketches and documents reveals a persistent ambition for large-scale works and a desire to be a universally significant composer from his early years. For instance, he attempted a symphony as early as 1832 and string quartets and a piano concerto in 1838-1839, foreshadowing later achievements.

2.2. Leipzig Period (1830-1844)

The Leipzig period marks Schumann's formative years as a composer, characterized by an intense focus on piano works and the emergence of his distinctive voice. His early compositions, from Op. 1 to Op. 23, were almost exclusively for piano, reflecting his initial ambition as a virtuoso performer. These include the programmatic PapillonsFrench (Papillons), (Op. 2), the virtuosic Toccata (Op. 7), and the character pieces CarnavalGerman (Carnaval) (Op. 9) and Symphonic Studies (Op. 13).

Following his marriage to Clara Wieck in 1840, Schumann's creative scope dramatically expanded. This year, known as his LiederjahrGerman (year of song), saw him compose over 120 Lieder, including the celebrated cycles MyrthenGerman (Myrthen, "Myrtles," a wedding present for Clara), Frauenliebe und LebenGerman (Frauen-Liebe und Leben, "Woman's Love and Life"), and DichterliebeGerman (Dichterliebe, "Poet's Love"), and settings of words by Joseph von Eichendorff, Heinrich Heine, and others. In these songs, he elevated the piano's role from mere accompaniment to an equal partner with the voice.

In 1841, he turned his attention to orchestral music, with his First Symphony, The Spring, which was premiered successfully by Mendelssohn. He also composed the Overture, Scherzo and Finale (Op. 52) and the original version of his Fourth Symphony (then in D minor). The year 1842 was dedicated to chamber music, yielding three string quartets (Op. 41), the highly influential Piano Quintet (Op. 44), and a Piano Quartet (Op. 47). The successful secular oratorio, Das Paradies und die PeriGerman (Das Paradies und die Peri), (Op. 50), completed in 1843, further cemented his reputation and brought him international recognition. During this period, he also taught at the newly founded Leipzig Conservatory, contributing to the city's vibrant musical life.

2.3. Dresden Period (1844-1850)

Schumann's move to Dresden in December 1844, partly for health reasons and partly in search of operatic opportunities, marked a shift in his compositional focus. Initially, his health remained poor, but it began to improve in early 1845. During this time, he and Clara studied counterpoint together, leading to contrapuntal works for piano. He completed his popular Piano Concerto (Op. 54) by adding a slow movement and finale to an earlier fantasy.

The Dresden period saw the composition of his Second Symphony (Op. 61), a work that reflected his triumph over personal crises. He also embarked on his only opera, Genoveva (Op. 81), which, despite its completion in 1848, was not a significant success. Schumann's interest in choral music grew, and he expanded a male voice choir into a mixed choir, leading to the composition of numerous choral works. Notable compositions from this period include the dramatic music to Lord Byron's Manfred (Op. 115) and significant portions of Szenen aus Goethes FaustGerman (Scenes from Goethe's Faust) (WoO 3), a monumental work that occupied him for nearly a decade. Other works include Forest Scenes (Op. 82) and Album for the Young (Op. 68) for piano, reflecting his family life. He also played a central role in the establishment of the Bach-Gesellschaft, an organization dedicated to publishing the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach.

2.4. Düsseldorf Period (1850-1854)

In September 1850, Schumann moved his family to Düsseldorf, where he had been appointed municipal music director. Initially, he was warmly welcomed, and his first concerts were successful. This period was marked by a surge of creative energy, producing two major works in quick succession: the Cello Concerto (Op. 129) and the Third Symphony, Rhenish (Op. 97). This period was also marked by an astonishing speed of composition; for instance, his Cello Concerto was completed in just two weeks, Symphony No. 3 in little over a month, and some works like the Hermann and Dorothea Overture in a matter of hours. He continued to compose prolifically, reworking earlier pieces like the D minor symphony from 1841, published as his Fourth Symphony (1851), and the 1835 Symphonic Studies (1852).

However, Schumann's introverted nature and worsening mental instability soon led to difficulties in his role as conductor. He struggled to communicate effectively with the orchestra and choir, often dropping his baton or continuing to conduct past the end of a piece. His diffidence and increasing reclusiveness caused relations with local musicians to deteriorate, leading to criticisms in the press and eventually his resignation in 1853.

Despite these professional challenges and his deteriorating mental health, Schumann continued to compose. His works from this period include the Violin Sonatas (Op. 105, Op. 121), the Third Piano Trio (Op. 110), the Violin Concerto (WoO 23), and sacred music such as his Mass (Op. 147) and Requiem (Op. 148).

A pivotal event in 1853 was the visit of the young Johannes Brahms, whom Schumann immediately recognized as a genius. He famously championed Brahms in his last critical essay, "Neue BahnenGerman" (New Paths), published in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. This encounter initiated a deep friendship and mentorship that would profoundly impact Brahms's career and provide crucial support to Clara Schumann during Robert's final years.

3. Musical Works

Robert Schumann's musical output is characterized by its profound Romantic sensibility, lyrical beauty, and innovative forms, particularly in his piano and vocal works.

3.1. Solo Piano

While his orchestral and operatic works have received mixed critical reception, there is widespread agreement on the high quality of Schumann's solo piano music. His early works, like the Abegg Variations (Op. 1), initially aligned with the flamboyant showpieces popular at the time. However, Schumann deeply revered earlier German masters like Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, as evidenced by his three piano sonatas (composed 1830-1836) and the Fantasie in C (1836), which show his respect for the Austro-German tradition of absolute music.

Most of his piano compositions are "character pieces with fanciful names," often grouped into cycles of short, interrelated, and subtly programmatic pieces. These include CarnavalGerman (Carnaval) (Op. 9), Fantasiestücke (Op. 12), Kreisleriana (Op. 16), Kinderszenen (Op. 15), and Waldszenen (Op. 82). Carnaval is particularly noted for its "wonderful animation and never-ending variety" and its technical demands. Schumann frequently embedded veiled allusions to himself and others, especially Clara, through musical ciphers and quotations, incorporating his "Florestan" (impetuous) and "Eusebius" (poetic) alter egos.

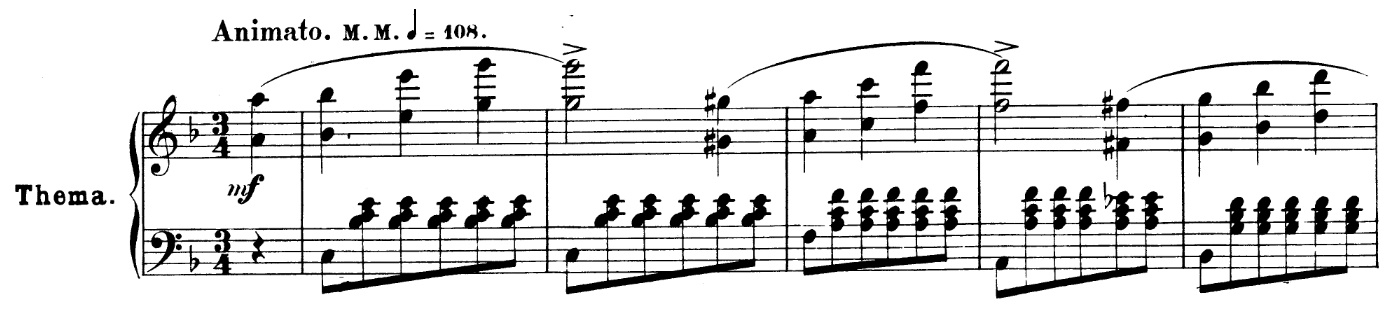

Schumann also composed simpler pieces for young players, most famously his Album für die Jugend (Op. 68, 1848) and Three Sonatas for Young People (1853). Some less demanding works, such as the Blumenstück (Op. 19) and Arabeske (Op. 18, both 1839), were written with commercial appeal in mind. His piano writing is notable for its distinctive use of pedals, creating atmospheric effects, and its frequent use of syncopation, often causing the perceived rhythm to differ from the written meter.

3.2. Lieder (Songs)

Schumann is regarded as one of the "four supreme masters of the German LiedGerman (Lied)" alongside Schubert, Brahms, and Hugo Wolf. He composed over 300 songs for voice and piano, celebrated for the high quality of the texts he chose. His youthful appreciation for literature continued throughout his adult life, guiding his selections. While he set a few verses by Goethe and Schiller, his preferred poets were later Romantics such as Heinrich Heine, Eichendorff, and Eduard Mörike.

Among his most famous songs are those from his LiederjahrGerman (year of song) in 1840. These include DichterliebeGerman (Dichterliebe, "Poet's Love", Op. 48), a cycle of sixteen songs on Heine's poetry; Frauenliebe und LebenGerman (Frauen-Liebe und Leben, "Woman's Love and Life", Op. 42), eight songs setting poems by Adelbert von Chamisso; and two sets simply titled LiederkreisGerman (Song Cycle)-the Op. 24 set of nine Heine settings and the Op. 39 set of twelve Eichendorff poems. Also from 1840 is MyrthenGerman (Myrthen, "Myrtles", Op. 25), a collection of twenty-six songs presented as a wedding gift to Clara.

Schumann's songs are notable for establishing an unprecedented equal partnership between words and music in the German Lied. His affinity with the piano is evident in his accompaniments, particularly in their preludes and postludes, which often summarize or extend the emotional content of the song. While it became common practice in the 20th century to perform these cycles as a whole, in Schumann's time, individual songs were often extracted for recitals. The first documented public performance of a complete Schumann song cycle was not until 1861, five years after his death, when Julius Stockhausen sang DichterliebeGerman with Brahms at the piano.

3.3. Orchestral Works

Schumann acknowledged that he found orchestration challenging, and many analysts have criticized his orchestral writing for its sometimes "thick" or "muffled" quality, awkward string parts, and a tendency for sections to play together constantly. Conductors like Gustav Mahler, Max Reger, and Arturo Toscanini have made alterations to his instrumentation. However, more recently, Schumann's orchestration has been more highly regarded, especially in performances by smaller forces and in historically informed readings, which reveal a warmer, more vibrant quality.

Schumann composed four symphonies. His First Symphony, The Spring (1841), was well-received at its premiere. His D minor symphony from 1841, revised and published as his Fourth Symphony in 1851, is often performed in its revised version, though Brahms preferred the original, more lightly scored version. The Second Symphony (1846) is structurally the most classical of the four, influenced by Beethoven and Schubert. The Third Symphony (1851), known as the Rhenish, is unusual for its five movements and is his closest approach to pictorial symphonic music, depicting scenes like a religious ceremony in Cologne Cathedral.

Schumann also experimented with unconventional symphonic forms in his Overture, Scherzo and Finale, Op. 52 (1841), sometimes called "a symphony without a slow movement." He composed six overtures, three for theatrical performance (preceding Lord Byron's Manfred, Goethe's FaustGerman (Scenes from Goethe's Faust), and his own Genoveva) and three stand-alone concert works inspired by Schiller's The Bride of Messina, Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, and Goethe's Hermann and Dorothea.

The Piano Concerto (Op. 54, 1845) quickly became and remains one of the most popular Romantic piano concertos, influencing works like Grieg's Piano Concerto. Its first movement notably contrasts the forthright Florestan and dreamy Eusebius elements of Schumann's artistic nature. While no other concerto by Schumann achieved its popularity, the Concert Piece for Four Horns and Orchestra (Op. 86, 1849) and the Cello Concerto (Op. 129, 1850) remain in the concert repertoire. The late Violin Concerto (WoO 23, 1853) is less frequently heard but has received several recordings. This work, composed during a period of declining health, was notably suppressed by Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim for many years after its composition, as they believed its quality was compromised. It was only published and premiered in the 1930s.

3.4. Chamber Music

Schumann composed a substantial quantity of chamber pieces, most notably the Piano Quintet in E♭ major, Op. 44, the Piano Quartet in the same key (both 1842), and three piano trios (Op. 63 and Op. 80 from 1847, and Op. 110 from 1851). The Piano Quintet, dedicated to Clara Schumann, is a brilliant work that incorporates a private message by quoting a theme composed by Clara. Schumann's use of piano and string quartet (two violins, viola, cello) in this work set a template for later composers including Brahms, César Franck, Gabriel Fauré, Dvořák, and Edward Elgar. The Piano Quartet is described as equally brilliant but more intimate. Schumann also composed a set of three string quartets (Op. 41, 1842), though after these, he largely avoided the genre, finding Beethoven's achievements daunting.

Later chamber works include the Sonata in A minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 105, and the Sonata in D minor for Violin and Piano, Op. 121, both written during an intense creative period in 1851. In addition to standard instrument combinations, Schumann wrote for unusual groupings and was often flexible about instrumentation. For example, his Adagio and Allegro, Op. 70, can be played by horn, violin, or cello with piano, and the FantasiestückeGerman, Op. 73, can feature clarinet, violin, or cello with piano. His Andante and Variations (1843) for two pianos, two cellos, and a horn was later arranged for two pianos alone.

3.5. Opera and Choral Works

Schumann's only opera, Genoveva (Op. 81), was not a great success in his lifetime and remains a rarity in the opera house. Critics often found it lacked dramatic action, describing it as "an evening of LiederGerman and nothing much else happens." However, proponents like conductor Nikolaus Harnoncourt argued that critics approached it with preconceived notions of opera, missing Schumann's intention to create a work where "the music had more to say" and was "a look into the soul" rather than naturalistic drama. Conversely, conductor Victoria Bond, who led its first professional US stage production, found it "full of high drama and supercharged emotion" and "very stageworthy."

Unlike his opera, Schumann's secular oratorio Das Paradies und die PeriGerman (Das Paradies und die Peri) (Op. 50), based on an episode from Thomas Moore's epic poem Lalla Rookh, was an enormous success in his lifetime, though it has since been neglected. Tchaikovsky called it a "divine work," and Simon Rattle described it as "The great masterpiece you've never heard." Schumann himself considered it "well-nigh a new genre for the concert hall."

Szenen aus Goethes FaustGerman (Scenes from Goethe's Faust) (WoO 3), composed between 1844 and 1853, is another hybrid work, operatic in style but intended for concert performance and labeled an oratorio. Despite its challenging, non-tuneful nature, the third section was successfully performed in 1849 to mark Goethe's centenary. The complete work premiered posthumously in 1862. Schumann's other major works for voice and orchestra include a Requiem Mass, which critic Ivan March described as "long-neglected and under-prized."

3.6. Sacred Music

Schumann's engagement with sacred music is often less understood than his other genres, yet he held a deep conviction that contributing creatively to religious music was the "highest purpose" for an artist. He believed that reading the Bible, Shakespeare, and Goethe provided all one needed. His time in Düsseldorf, where his duties as music director included performing Catholic liturgical music, further spurred his interest. He studied works by Palestrina, Bach, Handel, Haydn, and Mozart.

His sacred compositions include the motet Neunzigstes Psalm (Psalm 93, Op. 93, 1849), the Mass (Op. 147, 1852), and the Requiem (Op. 148, 1852). He also planned other sacred works, such as a Stabat Mater and a German Requiem based on Friedrich Rückert's poetry, though these were not realized. Critics have generally been harsh in their assessment of his sacred music, often citing weaknesses in structure and polyphony compared to his instrumental works, with some suggesting they are merely "musical records" rather than performance-worthy pieces.

4. Music Criticism

Robert Schumann played a significant role as a music critic, using his journalistic ventures to shape contemporary musical discourse and champion new talent.

4.1. Neue Zeitschrift für Musik and the Davidsbündler

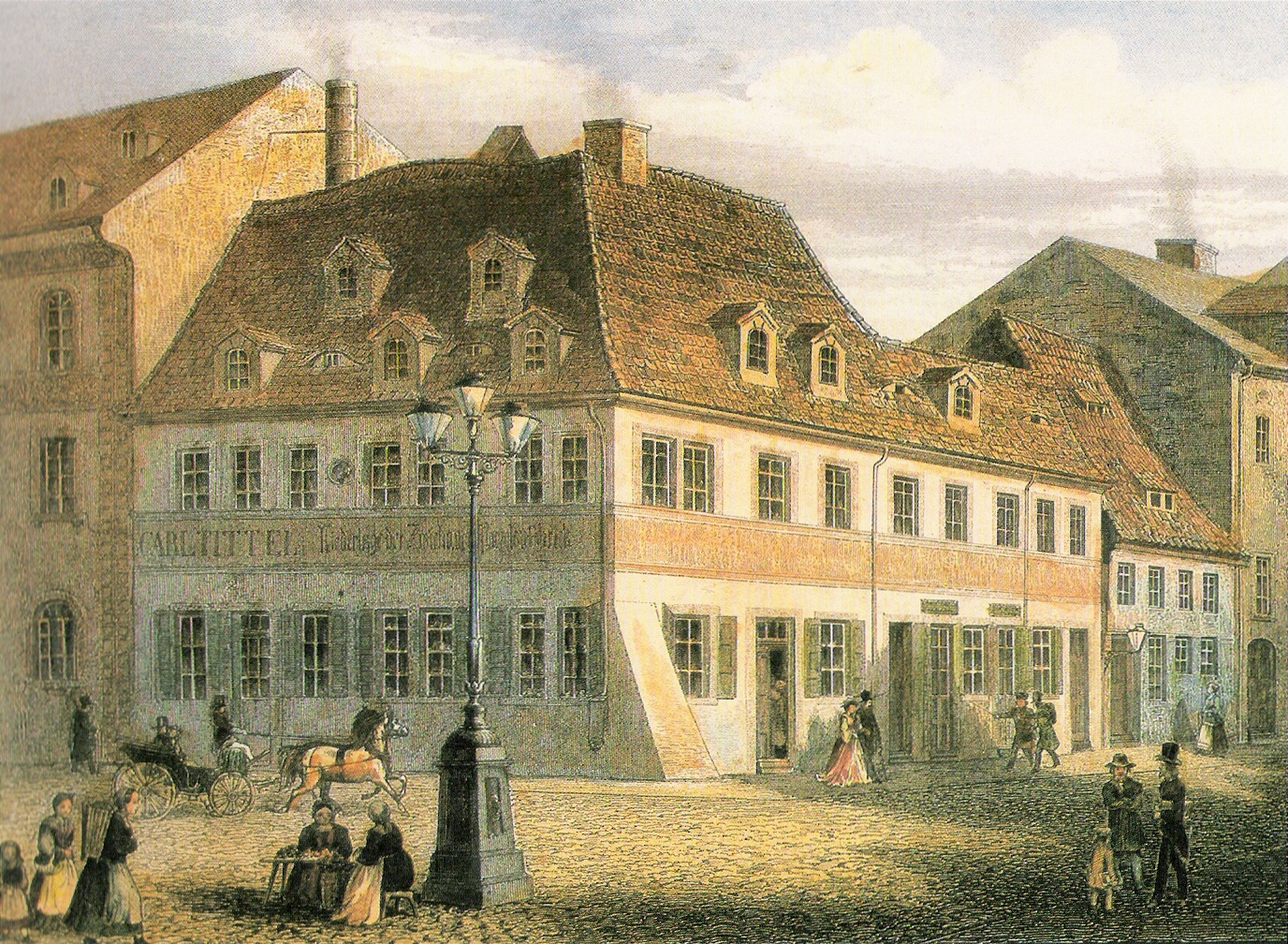

Schumann's music criticism began in 1832 with his famous essay, "Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!" in the Leipzig-based Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, introducing Frédéric Chopin to the world. Dissatisfied with the conservative and often superficial state of music criticism in Germany, Schumann, along with friends like Friedrich Wieck, Julius Knorr, and Ludwig Schunke, began discussions at Leipzig's Café BaumGerman about founding a new music journal. This led to the launch of the Neue Zeitschrift für MusikGerman (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik) on 3 April 1834.

Initially, Julius Knorr was the editor-in-chief, with Schumann assisting. However, due to Knorr's illness and the waning interest of others, Schumann soon took over sole editorship in January 1835, a role he held for ten years. The journal's purpose was to advocate for and recognize the value of young, innovative musicians who embodied the present and future of music, providing them with a platform to express themselves not just through their art but also through the written word. It represented a strong counter-attack against the conservative musical establishment of the time.

Within the pages of the Neue Zeitschrift, Schumann created the fictional DavidsbündlerGerman (Davidsbündler) (League of David)-a concept to battle the "Philistines" (musical mediocrities and conservatives). He used various pen names for his articles, often representing different facets of his own personality or his friends. The most prominent were "Florestan," symbolizing his impetuous and passionate side, and "Eusebius," representing his gentle and poetic nature. "Master Raro" (Meister RaroGerman) served as a wise arbiter, sometimes speculated to be a combination of Clara and Robert's names (Cla-RA-RO-bert) or a representation of Wieck. Other female pseudonyms like "Chiarina" (Clara Wieck), "Estrella" (Ernestine von Fricken), and "Zilia" (Henriette Voigt) were derived from women in his life. This playful approach intrigued readers, who tried to identify the real individuals behind the pseudonyms.

The "Davidsbündler" concept was not limited to his writings; it also appeared in his musical compositions. For example, in CarnavalGerman (Carnaval) (Op. 9, 1835), characters like Eusebius and Florestan appear, and the finale is titled "March of the Davidsbündler against the Philistines." His Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David, Op. 6, 1837) features "E," "F," or "E and F" markings for each piece, along with descriptive notes.

4.2. Critical Perspectives and Style

Schumann's music criticism aimed to poetically articulate the characteristics of new German music. He championed foreign composers like Chopin, Hector Berlioz, William Sterndale Bennett, and John Field, believing their genius was rooted in their respective times and cultures. Conversely, he was critical of Italian music, often likening Italians to "canaries" and attacking the spirit of bel cantoItalian and the "empty declamation" of composers like Giacomo Meyerbeer. He often used German titles and musical terms in his own compositions to distance himself from Italian conventions.

His witty, imaginative, and often poetic writing style captivated readers, and the Neue Zeitschrift für MusikGerman (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik) became the most influential music journal in Germany. Schumann quickly established himself as a leading voice in music journalism, initially gaining more fame as a critic than as a composer. His critical work also provided him with financial stability during his early career.

In 1844, Schumann stepped down as editor-in-chief of the Neue Zeitschrift, handing the reins to Oswald Lorenz, before moving to Dresden. Other notable contributors during his tenure included Carl Banck, Ludwig Böhner, and even Richard Wagner.

A decade later, in 1853, Schumann took up his pen again to write his last and most famous critical essay, "Neue BahnenGerman" (New Paths), introducing the young Johannes Brahms to the world. This essay, echoing his earlier discovery of Chopin, serves as a testament to the idea that "genius recognizes genius."

While Schumann's critical writings were groundbreaking, some later critics found them overly emotional and subjective. He was passionate about promoting his artistic vision but sometimes struggled to avoid biased judgments, particularly when advocating for the "New German School" (a term later used to describe the Liszt-Wagner camp, which ironically diverged from Schumann's own classical ideals). Nevertheless, his work laid the foundation for modern music criticism.

5. Relationships with Other Musicians

Robert Schumann's life and work were deeply intertwined with his relationships with contemporary and historical composers, influencing and being influenced by them.

5.1. Bach, Beethoven, and Schubert

Schumann held profound admiration for and was significantly influenced by Johann Sebastian Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Franz Schubert. He often referred to Bach as a "demigod of art" and the "root of all music," stating that "Bach is incomparable." After his marriage to Clara in 1840, they jointly studied Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier. In 1845, in Dresden, he acquired a pedal piano to study Bach's organ works, and in 1853, he composed piano accompaniments for Bach's solo violin sonatas and cello suites.

Beethoven's influence began early; Schumann played his piano works from age six and later performed his symphonies in piano duet arrangements. He owned scores of all nine Beethoven symphonies, most string quartets, Missa Solemnis, Fidelio, and piano concertos. Schumann's Fantasie in C (Op. 17) famously quotes from Beethoven's song cycle An die ferne Geliebte. Other works, like Album for the Young (Op. 68) and CarnavalGerman (Carnaval) (Op. 9), contain subtle allusions to Beethoven's compositions.

Schubert held a special place in Schumann's heart. He felt a deep affinity for Schubert's music from an early age, often playing his chamber works with friends and reportedly weeping all night upon hearing of Schubert's death in 1828. During his 1838-1839 stay in Vienna, Schumann visited Schubert's brother, Ferdinand, and made the momentous discovery of the manuscript for Schubert's Great C major Symphony. Schumann arranged for its premiere in Leipzig in March 1839, conducted by Mendelssohn, a discovery that profoundly influenced his own turn to symphonic composition in 1841.

5.2. Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Liszt

Schumann's relationship with Felix Mendelssohn was marked by deep respect. He saw Mendelssohn as the "Mozart of the 19th century" and greatly admired his talent. Their friendship, which began in 1835, lasted until Mendelssohn's death in 1847. While Schumann's admiration was immense, it was not unconditional. He sometimes criticized Mendelssohn's excessive expressiveness or differences in tempo interpretation, as seen in his comments on Mendelssohn's conducting of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.

Schumann was an early champion of Frédéric Chopin, famously introducing him to the world in his 1831 essay "Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!" He considered Chopin the finest pianist and composer in Paris and continued to review most of Chopin's published piano works in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. However, Schumann later expressed disappointment that Chopin did not venture into larger forms, and Chopin, in turn, showed little interest in Schumann's music or criticism.

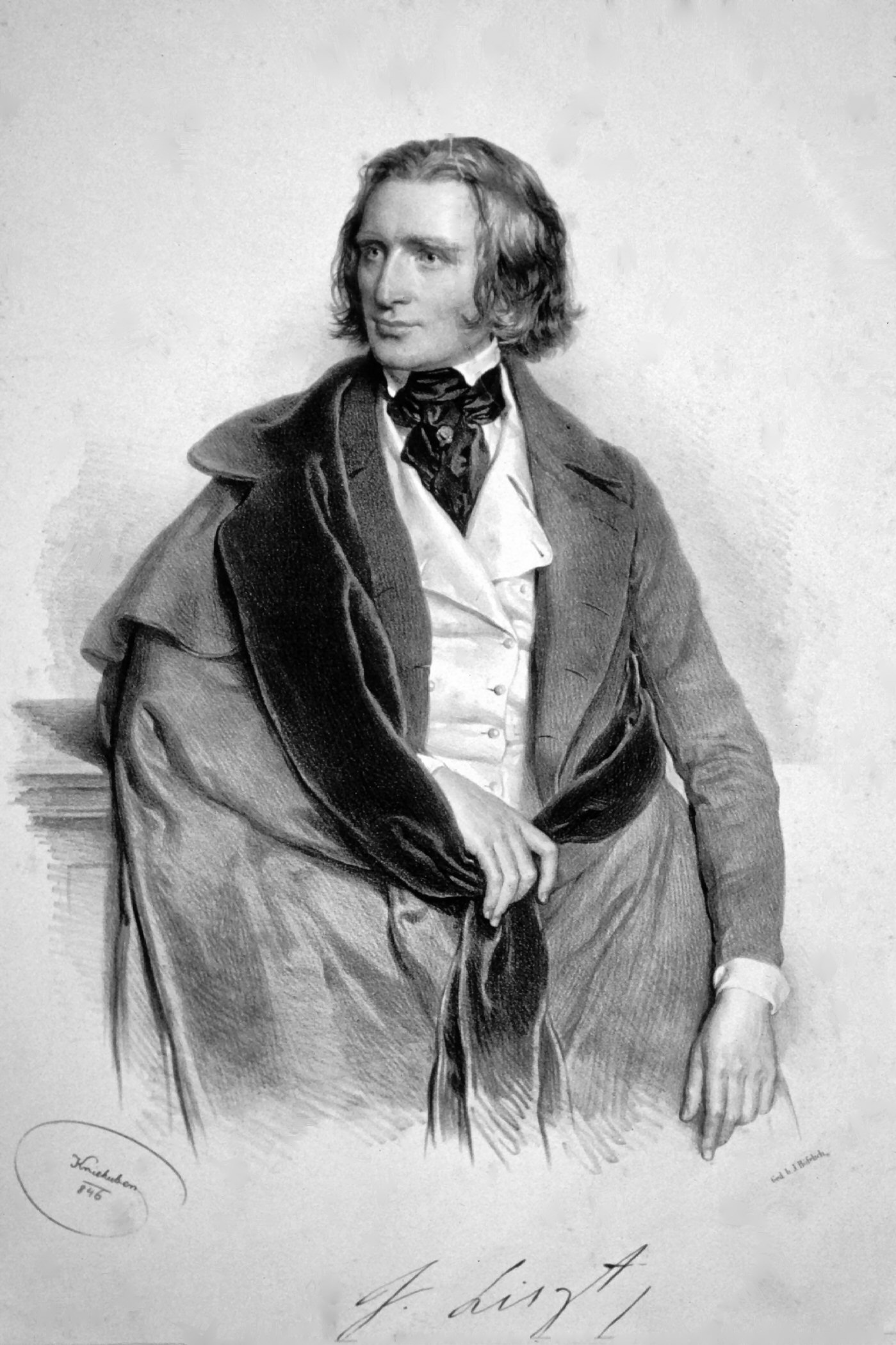

The relationship between Schumann and Franz Liszt was complex and evolved over time. Liszt was an early admirer of Schumann, recognizing his poetic musical ideals and his mastery of variation technique. He actively promoted Schumann's works in his concerts and encouraged Schumann to compose chamber music, foreseeing that the piano alone would become insufficient for him. Schumann initially felt a strong connection with Liszt, remarking that they felt like "acquaintances of twenty years." However, Schumann grew increasingly uncomfortable with Liszt's flamboyant personality and aristocratic leanings, while Clara called Liszt a "piano pulverizer." A famous altercation occurred in 1848 in Dresden, where Schumann, angered by Liszt's criticism of Mendelssohn, confronted him. This incident foreshadowed the later "War of the Romantics" between the conservative camp (Schumann, Brahms) and the progressive camp (Liszt, Wagner), with differing views on absolute music versus programmatic music. Despite their differences, Liszt continued to perform and conduct Schumann's works.

5.3. Brahms

The encounter between Schumann and the then twenty-year-old Johannes Brahms in September 1853 was a pivotal moment in music history. Brahms arrived at the Schumann household in Düsseldorf with a letter of introduction from Joseph Joachim and played his piano sonatas. Schumann was immediately captivated, exclaiming to Clara, "Now, my dear Clara, you will hear such music as you never heard before."

Schumann recognized Brahms's extraordinary talent, calling him a "young eagle" and predicting a brilliant future. He famously wrote his last critical essay, "Neue BahnenGerman" (New Paths), in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, hailing Brahms as a musician destined to express his times ideally. Brahms, deeply grateful for Schumann's patronage, became his most loyal disciple and a steadfast friend, providing immense personal and emotional support to Clara during Robert's final years. During his stay with the Schumanns, Robert, Brahms, and their pupil Albert Dietrich collaborated on the F.A.E. Sonata for Joachim.

5.4. Wagner

The relationship between Schumann and Richard Wagner was complex and often strained. Both were born in Leipzig (Wagner in 1813) and knew each other from the 1830s. Their paths crossed again when Wagner became music director at the Dresden Court Theatre, and Schumann moved to Dresden in 1844. However, they never truly connected.

Schumann disliked Wagner's operas, finding them influenced by Giacomo Meyerbeer and tainted by Italian tastes. He criticized Wagner's loquaciousness and perceived self-absorption, remarking that Wagner's "head is always full of his own ideas." Wagner, in turn, dismissed Schumann as too conservative and mocked his sensitive nature. Schumann conspicuously remained silent on Wagner's opera Tannhäuser, and while he noted its "genius brushstrokes," he never published a detailed review. This cautious stance foreshadowed the later "War of the Romantics," where Brahms, a close ally of Clara and Robert, maintained a similar distance from Wagner. Despite their mutual criticisms and differing musical philosophies-Schumann's commitment to the symphony and classical ideals versus Wagner's pursuit of "total art" and programmatic music-their interactions highlight the vibrant and often contentious musical landscape of 19th-century Germany.

6. Instruments

Among the musical instruments significant to Robert Schumann's life and career, the Conrad Graf grand piano stands out. This instrument was a wedding gift from the piano maker to Robert and Clara Schumann in 1839. It was kept in Schumann's study in Düsseldorf and later passed to Johannes Brahms from Clara Schumann. After several changes of ownership, it was acquired by the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde and is now displayed at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Other period instruments have been used in recordings of Schumann's works to capture the authentic sound of his era. For example, recordings have featured an 1837 Érard piano and an 1847 Streicher piano for his Piano Concerto, and an 1835 Graf piano for his Kinderszenen and Abegg Variations. These efforts aim to provide listeners with a historically informed performance that reflects the sonic qualities Schumann would have experienced.

7. Legacy and Assessment

Robert Schumann's profound impact on 19th-century music and his evolving critical reception are central to understanding his enduring legacy.

7.1. Musical Influence

Schumann's influence extended across Europe and beyond. French composers such as Gabriel Fauré and André Messager made a joint pilgrimage to his tomb in Bonn in 1879, and his music inspired Georges Bizet, Charles-Marie Widor, Claude Debussy, and Maurice Ravel, as well as the developers of symbolism. Pianist Alfred Cortot observed that Schumann's Kinderszenen influenced Bizet's Jeux d'enfants (1871), Chabrier's Pièces pittoresques (1881), Debussy's Children's Corner (1908), and Ravel's Ma mère l'Oye (1908).

In England, Edward Elgar called Schumann "my ideal," and Grieg's Piano Concerto is heavily influenced by Schumann's. Grieg also believed Schumann's songs deserved recognition as "major contributions to world literature." Schumann was a major influence on the Russian school of composers, including Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky. Despite Tchaikovsky's criticisms of Schumann's orchestration, he described him as a "composer of genius" and "the most striking exponent of the music of our time."

While Johannes Brahms famously quipped that all he learned from Schumann was how to play chess, other German-speaking composers whose music shows Schumann's influence include Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, and Arnold Schoenberg. More recently, Schumann has been an important influence on the music of Wolfgang Rihm, who has incorporated elements of Schumann's music into his chamber works (Fremde Szenen I-IIIGerman, 1982-1984) and opera Jakob LenzGerman (Jakob Lenz) (1977-1978). Other 20th and 21st-century composers drawing on Schumann include Mauricio Kagel, Wilhelm Killmayer, Henri Pousseur, and Robin Holloway.

7.2. Critical Reception

During the second half of the 19th century, a significant aesthetic debate, known as the "War of the Romantics," emerged. Schumann's successors, including Clara and Brahms, along with their supporters like Joachim and critic Eduard Hanslick, championed music in the classical German tradition of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Schumann. They were opposed by adherents of Liszt and Wagner, who favored more extreme chromatic harmonies and explicit programmatic content. Wagner, for instance, declared the symphony to be dead. By the turn of the century, however, critics began to evaluate the output of both factions with equal regard, moving beyond the polemics of the "War."

7.3. Complete Edition and Metronome Controversy

In 1991, the first volume of a new complete edition of Schumann's works was published. This initiative aimed to correct deficiencies in the supposedly complete edition published between 1879 and 1887, edited by Clara Schumann and Brahms. That earlier edition was not truly complete; in addition to inadvertent omissions, the editors deliberately suppressed some of Schumann's later music, believing it had been adversely affected by his declining mental health. In the 1980s, the University of Cologne established a research department to locate all of Schumann's manuscripts, leading to the 49-volume New Schumann Complete Edition, completed in 2023.

A notable controversy surrounding Schumann's works concerns his metronome markings. In 1861, Clara and Brahms discussed revising Schumann's metronome indications, with Brahms advising Clara to record her own performance speeds. While only five piano works had minor numerical changes, Clara's later 1887 edition of Schumann's piano works significantly revised the metronome markings. This led to a widespread belief, propagated by figures like conductor Hans von Bülow, that Schumann's metronome was faulty. However, Schumann himself reported checking his metronome and finding it accurate. Scholars like Alan Walker suggest that the issue originated with Clara, who may have altered tempos based on her own performing habits and then attributed "erratic" markings to a broken metronome. Walker also notes that composers' internal "performances" often lead to faster tempos than practical playing, which might explain some of Schumann's unusually fast markings.

Schumann's birthplace in Zwickau is preserved as a museum, hosting chamber concerts and an annual festival in his honor. The International Robert Schumann Competition for Piano and Voice, launched in Berlin in 1956 and later moved to Zwickau, continues to promote his legacy. In 2009, the Royal College of Music in London inaugurated the Joan Chissell Schumann Prize for singers and pianists. In 2005, the German federal government launched the online Schumann Network, a collaborative effort to provide comprehensive coverage of Robert and Clara Schumann's lives and works.

8. Chronology

- 1810:**

- June 8: Robert Schumann born in Zwickau, Kingdom of Saxony.

- June 14: Baptized at home.

- 1816:**

- Begins private preparatory school at age six.

- 1817:**

- Begins piano lessons with Johann Gottfried Kuntsch.

- Hears Carl Maria von Weber conduct a Beethoven symphony in Dresden.

- 1819:**

- Hears Ignaz Moscheles perform in Carlsbad, inspiring his pianistic ambitions.

- Attends a performance of Mozart's The Magic Flute in Leipzig.

- 1820:**

- Enters Zwickau Lyceum (Gymnasium) at age ten.

- 1823:**

- Begins contributing short pieces to his father's magazine.

- 1825:**

- Becomes leader of the "German Literature" circle at the Gymnasium.

- 1826:**

- Sister Emilie dies by suicide.

- August Schumann, his father, dies.

- Develops a passion for the works of Jean Paul.

- 1827:**

- Begins romantic relationships with Liddy Hemper and Nanni Patsch.

- Meets and develops a close relationship with Agnes Carus.

- 1828:**

- March: Graduates from Gymnasium with honors.

- Enters Leipzig University to study law.

- Travels to Bayreuth, Augsburg, Munich (meets Heinrich Heine).

- Begins piano studies with Friedrich Wieck in Leipzig.

- 1829:**

- May: Travels to Frankfurt, Koblenz, and arrives in Heidelberg.

- Transfers to Heidelberg University law faculty, participates in Professor Thibaut's music circle.

- August: Travels to Switzerland and Italy.

- 1830:**

- April: Hears Niccolò Paganini perform in Frankfurt, solidifying his decision to become a musician.

- October: Returns to Leipzig, resides at Wieck's house, and studies music theory with Heinrich Dorn.

- Composes Abegg Variations, Op. 1.

- 1831:**

- Leaves Wieck's residence but continues lessons with Dorn.

- Right hand injury begins to worsen.

- Composes PapillonsFrench (Papillons), Op. 2.

- 1832:**

- Decides to focus on composition due to hand injury.

- November: His Zwickau Symphony (unfinished) is premiered in Zwickau.

- Contributes his first music review, introducing Chopin, to the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung.

- Composes Paganini Studies, Op. 3.

- 1833:**

- October-November: Siblings Rosalie and Julius die, leading to symptoms of nervous exhaustion and depression.

- Composes Impromptus on a Theme by Clara Wieck, Op. 5.

- 1834:**

- Co-founds the Neue Zeitschrift für MusikGerman (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik).

- Begins a romantic relationship with Ernestine von Fricken, leading to a brief engagement.

- 1835:**

- Becomes sole editor of Neue Zeitschrift für MusikGerman (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik).

- Meets Felix Mendelssohn and Ignaz Moscheles in Leipzig.

- Reviews Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique in Neue Zeitschrift.

- December: Clara Wieck debuts in Leipzig, conducted by Mendelssohn.

- Composes CarnavalGerman (Carnaval), Op. 9, and Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 11.

- 1836:**

- February: His mother, Johanna, dies.

- Begins secret courtship with Clara Wieck.

- 1837:**

- August: Secretly engaged to Clara.

- September: Wieck rejects Schumann's request for marriage.

- Composes DavidsbündlertänzeGerman (Davidsbündlertänze), Op. 6, and Symphonic Studies, Op. 13.

- 1838:**

- October: Travels to Vienna, staying until April 1839.

- Composes Kinderszenen, Op. 15, and Kreisleriana, Op. 16.

- 1839:**

- January 1: Discovers Schubert's Great C major Symphony manuscript at Ferdinand Schubert's home in Vienna.

- Composes Blumenstück, Op. 19, and Nachtstücke, Op. 23.

- 1840:**

- "Year of Song" (LiederjahrGerman), composes over 120 Lieder.

- February: Awarded a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Jena University.

- March: Meets Franz Liszt in Leipzig.

- September 12: Marries Clara Wieck after a prolonged legal battle with her father.

- Composes Faschingsschwank aus Wien, Op. 26; LiederkreisGerman (Liederkreis), Op. 24 and Op. 39; MyrthenGerman (Myrthen), Op. 25; Frauenliebe und LebenGerman (Frauen-Liebe und Leben), Op. 42; and DichterliebeGerman (Dichterliebe), Op. 48.

- 1841:**

- "Year of Symphony."

- September: First daughter, Marie, born.

- Composes Symphony No. 1 (Spring) and the original version of Symphony No. 4 (D minor).

- 1842:**

- "Year of Chamber Music."

- Travels with Clara to Bremen and other cities.

- Composes three string quartets, Op. 41; Piano Quintet, Op. 44; and Piano Quartet, Op. 47.

- 1843:**

- "Year of Oratorio."

- Meets Hector Berlioz in Leipzig.

- April: Becomes professor at the Leipzig Conservatory.

- Second daughter, Elise, born.

- December: Reconciles with Friedrich Wieck.

- Completes the oratorio Das Paradies und die PeriGerman (Das Paradies und die Peri), Op. 50.

- 1844:**

- Travels with Clara on a five-month concert tour to Russia.

- Resigns as editor of Neue Zeitschrift für Musik.

- December: Resigns from Leipzig Conservatory and moves to Dresden.

- 1845:**

- Third daughter, Julie, born.

- Completes Piano Concerto, Op. 54.

- 1846:**

- February: First son, Emil, born.

- Travels with Clara to Vienna, Prague, and other cities.

- Composes Symphony No. 2, Op. 61.

- 1847:**

- June: Son Emil dies.

- July: A Schumann music festival is held in his hometown, Zwickau.

- November: Mendelssohn dies.

- Becomes conductor of the Liedertafel (male choir) and establishes a mixed choir.

- Composes Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 63, and Piano Trio No. 2, Op. 80.

- 1848:**

- January: Second son, Ludwig, born.

- Composes Album for the Young, Op. 68.

- 1849:**

- May: Flees Dresden to avoid the March Revolution unrest.

- July: Third son, Ferdinand, born.

- Composes opera Genoveva, Op. 81; Manfred Overture, Op. 115; and Waldszenen, Op. 82.

- 1850:**

- January: Das Paradies und die PeriGerman (Das Paradies und die Peri) is successfully performed.

- Accepts the position of municipal music director in Düsseldorf.

- June: Genoveva is staged in Leipzig.

- Plays a central role in founding the Bach-Gesellschaft.

- September: Moves to Düsseldorf.

- Composes Symphony No. 3 (Rhenish), Op. 97, and Cello Concerto, Op. 129.

- 1851:**

- Experiences increasing difficulties with the Düsseldorf orchestra and choir.

- December: Fourth daughter, Eugenie, born.

- Composes Der Rose Pilgerfahrt, Op. 112; Fantasiestücke, Op. 111; Piano Trio No. 3, Op. 110; Violin Sonata No. 1, Op. 105; and Violin Sonata No. 2, Op. 121.

- 1852:**

- Mental health symptoms worsen.

- Composes Requiem, Op. 148.

- 1853:**

- May: His revised Symphony No. 4 is successfully performed at the Lower Rhine Music Festival.

- September: Meets Johannes Brahms, publishes "Neue Bahnen" (New Paths) in Neue Zeitschrift für Musik to introduce him.

- Prepares his collected writings, Gesammelte Schriften über Musik und Musiker, for publication (published 1854).

- Composes Mass, Op. 147; Szenen aus Goethes FaustGerman (Scenes from Goethe's Faust); Violin and Orchestra Fantasy, Op. 131; and F.A.E. Sonata.

- 1854:**

- January: Travels to Hanover.

- February: Mental symptoms, including auditory hallucinations, worsen dramatically.

- February 27: Attempts suicide by jumping into the Rhine River, but is rescued.

- March 4: Voluntarily admitted to a sanatorium in Endenich, near Bonn.

- June: Fourth son, Felix, born.

- 1856:**

- July 29: Dies at the sanatorium at age 46.

- July 31: Buried in Bonn.