1. Early Life and Career

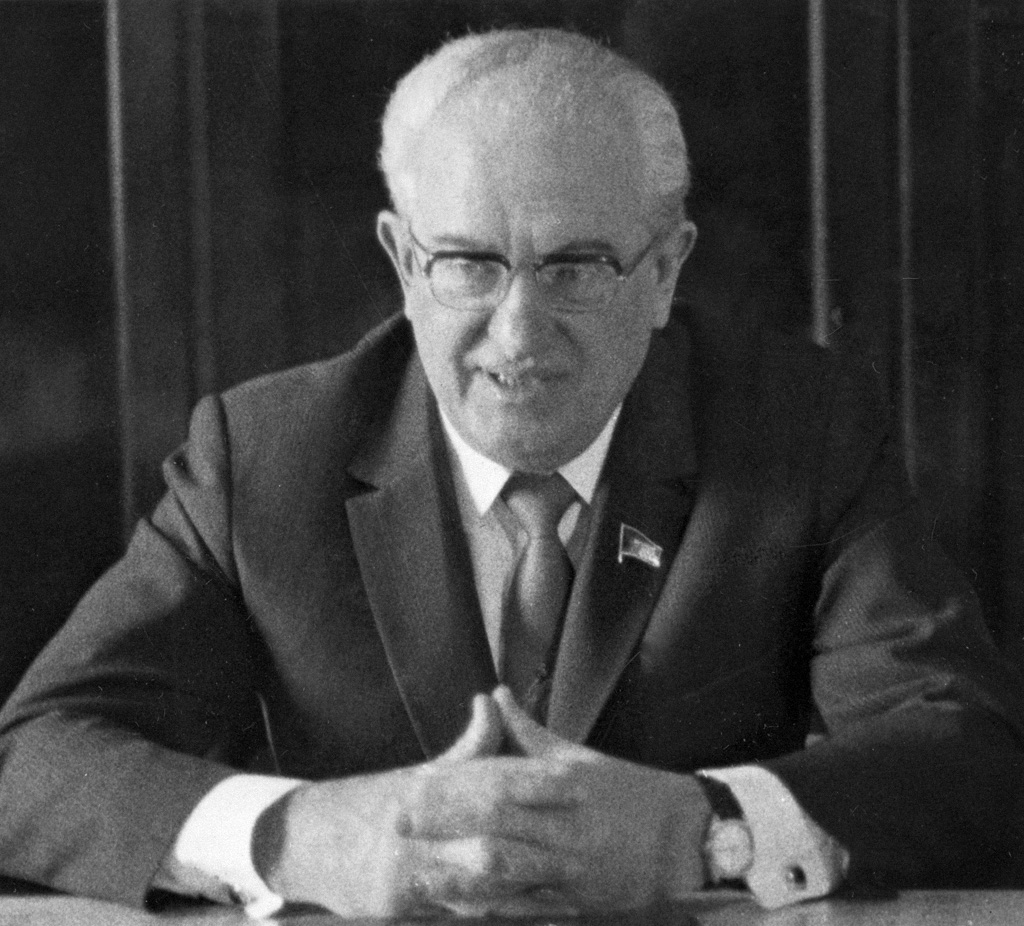

Leonid Brezhnev's early life and political activities laid the groundwork for his eventual rise to the pinnacle of Soviet power, starting from humble origins and navigating the complex political landscape of the Soviet Union.

1.1. Origins and Education

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev was born on December 19, 1906, in KamenskoyeKamianskeRussian, a working-class town in the Yekaterinoslav Governorate of the Russian Empire, now known as Kamianske, Ukraine. His father, Ilya Yakovlevich Brezhnev (1874-1934), was a metalworker, and his mother was Natalia Denisovna Mazalova (1886-1975). His parents had moved to Kamenskoye from Brezhnevo in Kursky District, Kursk Oblast, Russia, while his mother's parents hailed from Yenakiieve. While some documents, including his passport, listed his ethnicity as Ukrainian, he identified himself as Russian in his 1979 memoir, Memories, stating, "And so, according to nationality, I am Russian, I am a proletarian, a hereditary metallurgist."

Like many young people after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Brezhnev pursued a technical education, initially in land management and later in metallurgy. He studied at a vocational technical school in Kursk from 1924 to 1927, where he trained as a junior agricultural engineer specializing in land reclamation. He returned to Kamenskoye in 1930 and graduated from the Kamenskoye Metallurgical Technicum in 1935, subsequently working as a metallurgical engineer in the iron and steel industries of eastern Ukraine.

1.2. Early Political Activities

Brezhnev joined the Komsomol, the youth division of the Communist Party, in 1923. He officially became a member of the Party in 1929. From 1935 to 1936, he fulfilled his compulsory military service, attending a tank school before serving as a political commissar in a tank factory.

The Great Purge under Joseph Stalin in the late 1930s created numerous vacancies within the government and party ranks. Brezhnev, like many other young apparatchiks, exploited these opportunities to advance rapidly. In 1936, he became the director of the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum and was subsequently transferred to Dnipropetrovsk, a regional center. By May 1937, he was appointed deputy chairman of the Kamenskoye city soviet. After Nikita Khrushchev assumed control of the Ukrainian Communist Party in May 1938, Brezhnev was appointed head of the propaganda department of the Dnipropetrovsk regional Communist Party. In 1939, he was promoted to a regional Party Secretary, with responsibilities over the city's defense industries. It was during this period that Brezhnev began to establish a network of supporters, which later became known as the "Dnipropetrovsk Mafia," a group that would prove instrumental in his ascent to power.

2. World War II

Leonid Brezhnev's military career during World War II, known in the Soviet Union as the Great Patriotic War, was primarily focused on his role as a political commissar, maintaining party control and morale within the Red Army.

2.1. Military Service and Political Commissar Role

When Nazi Germany launched its invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Brezhnev, like most mid-ranking Party officials, was immediately drafted into the military. He was initially involved in the evacuation of Dnipropetrovsk's industries before the city fell to German forces on August 26. Following this, he was assigned as a political commissar. In October 1941, Brezhnev was made deputy of political administration for the Soviet Southern Front with the rank of Brigade-Commissar, equivalent to a Colonel.

In 1942, as German forces occupied much of Ukraine, Brezhnev was transferred to the Caucasus as deputy head of political administration for the Transcaucasian Front. By April 1943, he became the head of the Political Department of the 18th Army. Later that year, the 18th Army became part of the 1st Ukrainian Front as the Red Army regained the initiative and advanced westward through Ukraine. During this period, the Front's senior political commissar was Nikita Khrushchev, who had been a patron of Brezhnev's career since before the war, having first met him in 1931. Brezhnev's rapid ascent through the ranks was largely due to Khrushchev's support. By the end of the war in Europe, Brezhnev was the chief political commissar of the 4th Ukrainian Front, which entered Praha in May 1945 after the German surrender.

3. Rise to Power

After World War II, Leonid Brezhnev systematically climbed the ranks of the Soviet political system, leveraging strategic alliances and political maneuvering to eventually assume the supreme leadership of the country.

3.1. Post-War Ascendancy

Brezhnev officially left the Soviet Army with the rank of major general in August 1946, having spent the war as a political commissar rather than a military commander. In May 1946, he was appointed first secretary of the Zaporizhzhia regional party committee, where Andrei Kirilenko, a key member of the "Dnipropetrovsk Mafia," served as his deputy. After engaging in reconstruction projects in Ukraine, Brezhnev returned to Dnipropetrovsk in January 1948 as regional first party secretary.

In 1950, Brezhnev became a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the country's highest legislative body. In July of the same year, he was transferred to the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic and appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party of Moldavia. In this role, he was responsible for overseeing the completion of collective agriculture and the forced transfer of thousands of ethnic Romanians to other parts of the Soviet Union. During his time in Moldavia, he brought loyal figures with him from Dnipropetrovsk, including Konstantin Chernenko, who headed the agitprop department, and Nikolai Shchelokov, who would later become the USSR Minister of the Interior, further solidifying his network.

In 1952, Brezhnev met with Joseph Stalin, who subsequently promoted him to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as a candidate member of the Presidium (formerly the Politburo) and made him a member of the Secretariat. However, following Stalin's death in March 1953, Brezhnev experienced a demotion, being reassigned as first deputy head of the political directorate of the Army and Navy.

3.2. Advancement under Nikita Khrushchev

Brezhnev's patron, Nikita Khrushchev, succeeded Stalin as General Secretary, while Khrushchev's rival, Georgy Malenkov, became Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Brezhnev sided with Khrushchev against Malenkov for several years. In February 1954, Brezhnev was appointed Second Secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan, and in May, he was promoted to First Secretary, following Khrushchev's victory over Malenkov. His ostensible mission was to make the new lands agriculturally productive, a task related to the Virgin Lands Campaign. However, in reality, Brezhnev also became involved in the development of Soviet missile and nuclear arms programs, including the Baikonur Cosmodrome. The initial success of the Virgin Lands Campaign soon faltered, failing to resolve the burgeoning Soviet food crisis. Consequently, Brezhnev was recalled to Moscow in 1956, avoiding direct political fallout from the disappointing harvests.

In February 1956, Brezhnev returned to Moscow as a candidate member of the Politburo, where he was tasked with controlling the defense industry, the space program, heavy industry, and capital construction. He became a senior member of Khrushchev's inner circle, and in June 1957, he decisively backed Khrushchev against Malenkov's Stalinist old guard in the "Anti-Party Group" power struggle. Following the defeat of the Stalinists, Brezhnev became a full member of the Politburo. In May 1960, he was further promoted to the post of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, making him the nominal head of state. Despite this prestigious title, real power remained with Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party and Premier.

3.3. Ouster of Khrushchev and Assumption of Leadership

Khrushchev's position as Party leader remained secure until around 1962. However, as he aged, his leadership became increasingly erratic, undermining the confidence of his colleagues. The escalating economic problems within the Soviet Union further intensified pressure on Khrushchev's leadership. Although Brezhnev publicly maintained loyalty to Khrushchev, he became involved in a 1963 plot to remove him from power, possibly playing a leading role. In the same year, Brezhnev succeeded Frol Kozlov, another Khrushchev protégé, as Secretary of the Central Committee, positioning him as Khrushchev's most likely successor. Khrushchev then appointed him Second Secretary, or deputy party leader, in 1964.

After returning from Scandinavia and Czechoslovakia in October 1964, Khrushchev, unaware of the impending conspiracy, went on holiday to the Pitsunda resort on the Black Sea. Upon his return, his Presidium officers congratulated him on his work. Anastas Mikoyan visited Khrushchev, hinting that he should not be overly complacent about his situation. Vladimir Semichastny, head of the KGB, was a crucial part of the conspiracy, as it was his duty to inform Khrushchev of any plots against his leadership. Nikolay Ignatov, whom Khrushchev had previously dismissed, discreetly sought the opinions of several Central Committee members. After some initial delays, fellow conspirator Mikhail Suslov telephoned Khrushchev on October 12, requesting his return to Moscow to discuss the state of Soviet agriculture. Realizing what was happening, Khrushchev told Mikoyan, "If it's me who is the question, I will not make a fight of it." While a minority, led by Mikoyan, wished to remove Khrushchev only from the First Secretary position but retain him as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the majority, headed by Brezhnev, sought to remove him from active politics entirely.

Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny appealed to the Central Committee, blaming Khrushchev for economic failures and accusing him of voluntarism and immodest behavior. Influenced by Brezhnev's allies, Politburo members voted on October 14 to remove Khrushchev from office. Some members of the Central Committee desired further punishment for Khrushchev, but Brezhnev, who had already secured the General Secretary office, saw little reason for additional punitive measures. Brezhnev was appointed First Secretary on the same day. Initially, he was widely regarded as a transitional leader, merely holding the position until a more permanent leader could be appointed. Alexei Kosygin was appointed head of government, and Mikoyan remained head of state. Brezhnev and his allies supported the general party line established after Stalin's death but believed that Khrushchev's reforms had eroded Soviet stability. One primary reason for Khrushchev's ouster was his consistent tendency to overrule other party members, which the plotters viewed as "contempt of the party's collective ideals." The Soviet newspaper Pravda subsequently highlighted new enduring themes, such as collective leadership, scientific planning, consultation with experts, organizational regularity, and an end to ad-hoc schemes. Khrushchev's departure from the public spotlight generated no popular commotion, as most Soviet citizens, including the intelligentsia, anticipated a period of stabilization, steady societal development, and sustained economic growth.

Political scientist George W. Breslauer has contrasted Khrushchev and Brezhnev's leadership styles, noting that they adopted different approaches to building legitimate authority based on their personalities and public opinion. Khrushchev aimed to decentralize the government and empower local leadership, which had been completely subservient. In contrast, Brezhnev sought to centralize authority, even weakening the roles of other Central Committee and Politburo members.

3.3.1. Consolidation of Authority

Upon replacing Khrushchev as the party's First Secretary, Brezhnev became the de jure supreme authority of the Soviet Union. However, he was initially compelled to govern as part of an unofficial triumvirate, also known as a Troika, alongside Premier Alexei Kosygin and Nikolai Podgorny, who was a Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and later Chairman of the Presidium. This arrangement was formalized by a Central Committee plenum in October 1964, which, in reaction to Khrushchev's disregard for the Politburo and his combination of party and government leadership, forbade any single individual from holding both the General Secretary and Premier offices simultaneously. This collective leadership structure would persist until the late 1970s, when Brezhnev decisively secured his position as the most powerful figure in the Soviet Union.

During his consolidation of power, Brezhnev first addressed the ambitions of Alexander Shelepin, the former KGB chairman and then head of the Party-State Control Committee. In early 1965, Shelepin began advocating for the restoration of "obedience and order" in the Soviet Union as part of his bid for power. He exploited his control over state and party organs to garner support within the regime. Recognizing Shelepin as an immediate threat, Brezhnev mobilized the Soviet collective leadership to remove him from the Party-State Control Committee, which was subsequently dissolved on December 6, 1965.

By the end of 1965, Brezhnev had also maneuvered to have Podgorny removed from the Secretariat, significantly limiting his ability to build support within the party apparatus. Over the ensuing years, Podgorny's network of supporters was steadily eroded as his protégés were forcibly "retired" from the Central Committee. Although Podgorny quickly became the second most powerful figure in the country when his authority as Chairman of the Presidium was expanded in 1973, his influence over Soviet policy continuously declined relative to Brezhnev's, especially after Brezhnev bolstered his support within the national security apparatus. By 1977, Brezhnev was secure enough to replace Podgorny as head of state and remove him from the Politburo, cementing his own role as the undisputed leader.

After sidelining Shelepin and Podgorny in 1965, Brezhnev turned his attention to his remaining political rival, Alexei Kosygin. In the 1960s, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger initially perceived Kosygin as the dominant figure in Soviet foreign policy within the Politburo. Concurrently, Kosygin also managed economic administration as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. However, his position weakened following his enactment of several economic reforms in 1965, collectively known as the "Kosygin reforms." These reforms, coinciding with the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia (whose sharp deviation from the Soviet model led to its armed suppression in 1968), provoked a backlash among the party's old guard. This opposition flocked to Brezhnev, strengthening his position within the Soviet leadership. In 1969, Brezhnev further expanded his authority after a clash with Second Secretary Mikhail Suslov and other party officials, who never again challenged his supremacy within the Politburo.

Brezhnev proved adept at navigating the Soviet power structure. He was a team player, careful not to act rashly or hastily. Unlike Khrushchev, he made decisions only after substantial consultation with his colleagues and was always willing to consider their opinions. During the early 1970s, Brezhnev solidified his domestic position. In 1977, he forced Podgorny's retirement and once again became Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, effectively making this position equivalent to that of an executive president. While Kosygin remained Premier until shortly before his death in 1980 (when he was replaced by Nikolai Tikhonov), Brezhnev had established himself as the dominant figure in the Soviet Union from the mid-1970s until his death in 1982. He also interfered in economic policy, which was Kosygin's domain, further expanding his influence.

4. Leader of the Soviet Union (1964-1982)

Leonid Brezhnev's eighteen-year leadership of the Soviet Union, known as the "Brezhnev Era," was a period of both significant international influence and growing domestic challenges, particularly economic stagnation and political repression.

4.1. Domestic Policies

The internal policies under Brezhnev's leadership were marked by a conservative approach that stifled liberalization, led to economic stagnation, and maintained a rigid social structure.

4.1.1. Ideological Development and 'Developed Socialism'

Brezhnev articulated the concept of "Developed Socialism," which he presented as the Soviet-style socialism that had successfully built socialism in the Soviet Union and reached Vladimir Lenin's transitional stage from socialism to communism. Brezhnev emphasized the advanced technological developments in the USSR, including the full electrification of the country, the use of nuclear power in production, computer planning, and highly mechanized agriculture. He asserted that all social strata within the USSR were closer than ever before due to the country's highly developed productive forces. Consequently, according to Brezhnev, the dictatorship of the proletariat had evolved into a people's government. Brezhnev believed that all socialist countries, irrespective of their national and material conditions, would undergo the same socialist development and social transformation according to the Soviet model.

4.1.2. Political Repression and Human Rights

Brezhnev's stabilization policy included a reversal of Khrushchev's liberalizing reforms and a clamping down on cultural freedom. During the Khrushchev years, Brezhnev had supported the denunciation of Stalin's arbitrary rule, the rehabilitation of many purge victims, and the cautious liberalization of Soviet intellectual and cultural policy. However, upon becoming leader, he began to reverse this trend, adopting an increasingly authoritarian and conservative stance.

By the mid-1970s, an estimated 5,000 political and religious prisoners were held across the Soviet Union, enduring severe conditions and malnutrition. Many were deemed "mentally unfit" by the Soviet state and confined to mental asylums, a practice known as political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union. Under Brezhnev's rule, the KGB, led by Yuri Andropov, extensively infiltrated anti-government organizations, ensuring minimal opposition to the regime. However, Brezhnev largely refrained from the widespread, all-out violence seen under Stalin's rule.

The trial of writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966, the first such public trials since Stalin's era, signaled the return to a repressive cultural policy. While the KGB regained much of its power under Andropov, there was no return to the purges of the 1930s and 1940s, and Stalin's legacy remained largely discredited among the Soviet intelligentsia. This period also saw policies of Russification in various Soviet republics, with a decrease in the proportion of children taught in their native languages and restrictions on local-language media, accompanied by the imprisonment of "nationalists."

4.1.3. Economic Performance and the 'Era of Stagnation'

Between 1960 and 1970, Soviet agricultural output increased by 3% annually. Industrial production also saw improvement: during the Eighth Five-Year Plan (1966-1970), the output of factories and mines grew by 138% compared to 1960 levels. Despite the Politburo's increasingly anti-reformist stance, Kosygin managed to secure approval from Brezhnev and the Politburo to allow the Hungarian People's Republic to implement its "New Economic Mechanism" (NEM), which permitted limited retail markets. In the Polish People's Republic, under Edward Gierek, a different approach was taken in 1970, seeking Western loans to accelerate heavy industry growth. The Soviet leadership approved this, as the Soviet Union could no longer afford its massive subsidies to the Eastern Bloc through cheap oil and gas exports. However, not all reforms were accepted, as demonstrated by the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 in response to Alexander Dubček's reforms. Under Brezhnev, the Politburo abandoned Khrushchev's decentralization experiments, and by 1966, Brezhnev abolished the Regional Economic Councils that managed regional economies.

The Ninth Five-Year Plan (1971-1975) marked a shift: for the first time, industrial consumer products out-produced industrial capital goods. Consumer items like watches, furniture, and radios were produced in abundance. However, the plan still directed the majority of state investment towards industrial capital-goods production. This outcome was not viewed positively by most top party functionaries, and by 1975, consumer goods were expanding 9% slower than industrial capital-goods. This policy persisted despite Brezhnev's stated commitment to rapidly shift investment to satisfy Soviet consumers and improve living standards, which ultimately did not occur.

| Period | Annual GNP growth (CIA estimates) | Annual NMP growth (Grigorii Khanin estimates) | Annual NMP growth (USSR official figures) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960-1965 | 4.8% | 4.4% | 6.5% |

| 1965-1970 | 4.9% | 4.1% | 7.7% |

| 1970-1975 | 3.0% | 3.2% | 5.7% |

| 1975-1980 | 1.9% | 1.0% | 4.2% |

| 1980-1985 | 1.8% | 0.6% | 3.5% |

Before 1973, the Soviet economy was growing at a faster, albeit small, rate than the American economy and maintained a steady pace with Western European economies. Between 1964 and 1973, Soviet economic output per capita was roughly half that of Western Europe and slightly more than one-third that of the U.S. By the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had the world's second-largest industrial capacity, producing more steel, oil, pig-iron, cement, and tractors than any other country. However, this period of catching up with the West ended around 1973, as the Soviet Union increasingly lagged in computer technology, which proved crucial for Western economies. It was around this time that the "Era of Stagnation" became apparent.

The Era of Stagnation, a term coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, stemmed from a combination of factors. These included the ongoing arms race, the Soviet Union's engagement in international trade without adapting to changes in Western societies, increased authoritarianism, the costly Soviet-Afghan War, the transformation of the bureaucracy into an undynamic gerontocracy, a lack of meaningful economic reform, pervasive political corruption, and other structural problems. Domestically, social stagnation was exacerbated by growing demands from unskilled workers, labor shortages, and declining productivity and labor discipline. Although Brezhnev, albeit sporadically, attempted to reform the economy through Alexei Kosygin in the late 1960s and 1970s, these efforts yielded few positive results. The 1965 economic reform, initiated by Kosygin, was ultimately canceled by the Central Committee, despite the committee acknowledging the existence of economic problems. Gorbachev would later characterize the economy under Brezhnev's rule as "the lowest stage of socialism."

Based on its surveillance, the CIA reported that the Soviet economy peaked in the 1970s, reaching 57% of American GNP. However, starting around 1975, economic growth began to decline, partly due to the regime's sustained prioritization of heavy industry and military spending over consumer goods. Furthermore, Soviet agriculture struggled to feed the urban population, let alone provide for the rising standard of living promised as the fruits of "mature socialism" and on which industrial productivity depended. Ultimately, the GNP growth rate slowed to 1% to 2% per year. As GNP growth rates decreased in the 1970s from the levels held in the 1950s and 1960s, they also began to fall behind those of Western Europe and the United States. Eventually, the stagnation reached a point where the United States began growing at an average of 1% per year faster than the Soviet Union.

The stagnation of the Soviet economy was further fueled by its ever-widening technological gap with the West. Due to the cumbersome procedures of the centralized planning system, Soviet industries were incapable of the innovation needed to meet public demand, particularly in the field of computers. In response to the lack of uniform standards for peripherals and digital capacity, Brezhnev's regime ordered an end to all independent computer development, requiring all future models to be based on the IBM System/360. However, after adopting the IBM/360 system, the Soviet Union was never able to build enough platforms or improve on its design. As its technology continued to lag behind the West, the Soviet Union increasingly resorted to pirating Western designs.

The last significant reform undertaken by the Kosygin government, and arguably in the pre-perestroika era, was a joint decision by the Central Committee and the Council of Ministers in 1979, aimed at "Improving planning and reinforcing the effects of the economic mechanism on raising the effectiveness in production and improving the quality of work." This "1979 reform," in contrast to the 1965 reform, sought to increase the central government's economic involvement by enhancing the duties and responsibilities of the ministries. However, with Kosygin's death in 1980 and his successor Nikolai Tikhonov's conservative approach to economics, very little of the reform was actually implemented.

The Eleventh Five-Year Plan (1981-1985) delivered disappointing results, with growth rates declining from 5% to 4%. The previous Tenth Five-Year Plan had aimed for 6.1% growth but failed to meet this target. Brezhnev managed to defer economic collapse by trading with Western Europe and the Arab World, especially as the Soviet Union benefited from being the world's largest oil producer during the oil shocks of the 1970s. However, this reliance on natural resources meant that the foreign currency earned was largely spent on importing high-tech equipment, grain, and luxury goods from the West, hindering the transformation of the heavy industry-centric economy. A dramatic consequence of Brezhnev's rule was that some Eastern Bloc countries became more economically advanced than the Soviet Union itself.

4.1.4. Agricultural Policy

Brezhnev's agricultural policy largely reinforced traditional methods of organizing collective farming, with output quotas centrally imposed. Khrushchev's policy of amalgamating farms was continued by Brezhnev, who shared the belief that larger kolkhozes would increase productivity. Brezhnev advocated for increased state investments in farming, which reached an all-time high in the 1970s, accounting for 27% of all state investment, excluding investments in farm equipment. In 1981 alone, 33.00 B USD (at contemporary exchange rates) was invested into agriculture.

Agricultural output in 1980 was 21% higher than the average production rate between 1966 and 1970, with cereal crop output increasing by 18%. However, these improvements were not entirely encouraging. The primary criterion for assessing agricultural output in the Soviet Union was the grain harvest. The import of cereal, which began under Khrushchev, had become a normal phenomenon by Soviet standards due to a severe deficiency in domestic fodder crop production. When Brezhnev faced difficulties securing commercial trade agreements with the United States, he turned to other countries, such as Argentina. Another struggling sector was the sugar beet harvest, which had declined by 2% in the 1970s.

Brezhnev's approach to these issues was to increase state investment. Politburo member Gennady Voronov proposed dividing each farm's workforce into "links," units entrusted with specific functions, such as running a farm's dairy unit. His argument was that larger workforces felt less responsible. This program, initially proposed to Joseph Stalin by Andrey Andreyevich Andreyev in the 1940s and opposed by Khrushchev, was also rejected by Brezhnev, leading to Voronov's removal from the Politburo in 1973.

Despite the official stance, experimentation with "links" was not entirely disallowed at the local level. For instance, Mikhail Gorbachev, then First Secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee, experimented with links in his region. Overall, the Soviet government's involvement in agriculture was, according to Robert Service, "unimaginative" and "incompetent." Facing mounting agricultural problems, the Politburo issued a resolution titled, "On the Further Development of Specialisation and Concentration of Agricultural Production on the Basis of Inter-Farm Co-operation and Agro-Industrial Integration." This resolution mandated that adjacent kolkhozes collaborate to increase production. However, state subsidies to the food-and-agriculture sector failed to prevent bankrupt farms from operating, and rising produce prices were offset by increases in the cost of oil and other resources. By 1977, oil cost 84% more than it did in the late 1960s, with other resource costs also climbing.

Brezhnev's response to these challenges was to issue two decrees, one in 1977 and another in 1981, which called for an increase in the maximum size of privately owned plots within the Soviet Union to half a hectare. While these measures removed significant obstacles to expanding agricultural output, they did not resolve the fundamental problems. Under Brezhnev, private plots, cultivating only 4% of the land, yielded 30% of the national agricultural production. This led some to believe that de-collectivization was necessary to prevent the collapse of Soviet agriculture, but leading Soviet politicians shied away from such drastic measures due to ideological and political considerations. The underlying issues included a growing shortage of skilled workers, a damaged rural culture, a system of worker payment based on quantity rather than quality of work, and farm machinery that was too large for small collective farms and the often roadless countryside. Faced with these challenges, Brezhnev's only options were large-scale land reclamation and irrigation projects, as radical reforms were avoided.

4.1.5. Society and Living Standards

Over the eighteen years of Brezhnev's rule, average income per capita in the Soviet Union increased by half, with three-quarters of this growth occurring in the 1960s and early 1970s. During the latter half of his premiership, average income per capita grew by one-quarter. In the first half of the Brezhnev period, income per capita increased by 3.5% per annum, a slightly lower rate than previous years, partly due to Brezhnev's reversal of most of Khrushchev's policies. Consumption per capita rose by an estimated 70% under Brezhnev, with three-quarters of this growth taking place before 1973 and only one-quarter in the second half of his rule. Much of the early increase in consumer production can be attributed to the Kosygin reform.

Despite the USSR's economic growth stalling in the 1970s, the overall standard of living and housing quality for Soviet citizens improved significantly. Rather than focusing solely on the economy, the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev sought to improve living standards by expanding social benefits, which led to a minor increase in public support. However, living standards in the RSFSR lagged behind those in the Georgian SSR and the Estonian SSR, leading many Russians to believe that Soviet government policies were disadvantaging the Russian population. The state frequently reassigned workers from one job to another, a pervasive feature of Soviet industry. Government industries, including factories, mines, and offices, were staffed by undisciplined personnel who often made little effort to perform their duties, leading to what Robert Service termed a "work-shy workforce." The Soviet Government lacked effective countermeasures, as it was exceedingly difficult to replace ineffective workers due to the country's lack of unemployment.

While some areas saw improvement during the Brezhnev era, the majority of civilian services deteriorated, and living conditions for Soviet citizens declined rapidly. Diseases were on the rise due to a decaying healthcare system. Living space remained rather small by First World standards, with the average Soviet person occupying only 144 ft2 (13.4 m2). Thousands of Moscow residents became homeless, living in shacks, doorways, and parked trams, while food rationing returned to cities like Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) in the late 1970s.

The state did provide recreation facilities and annual holidays for diligent citizens, with Soviet trade unions rewarding hard-working members and their families with beach vacations in Crimea and Georgia.

Social rigidification became a common feature of Soviet society. In contrast to the Stalin era of the 1930s and 1940s, where a common laborer could aspire to a white-collar job through study and obedience to Soviet authorities, this was no longer the case in Brezhnev's Soviet Union. Individuals holding desirable positions clung to them for as long as possible; mere incompetence was not considered sufficient grounds for dismissal. This contributed to the static nature of Soviet society that Brezhnev bequeathed to his successors.

4.2. Foreign and Defense Policies

Brezhnev's foreign policy during his leadership sought to expand Soviet global influence and manage Cold War tensions, often through military strength and strategic interventions.

4.2.1. Intervention in Czechoslovakia and the Brezhnev Doctrine

The first major crisis for Brezhnev's regime emerged in 1968 with the attempt by the Communist leadership in Czechoslovakia, under Alexander Dubček, to liberalize the Communist system, an event known as the Prague Spring. In July, Brezhnev publicly denounced the Czechoslovak leadership as "revisionist" and "anti-Soviet." Despite his hardline public statements, archival evidence suggests that Brezhnev was not the strongest proponent of military force in Czechoslovakia when the issue was debated within the Politburo. He initially sought a temporary compromise with the reform-friendly Czechoslovak government. However, facing mounting pressure within the Soviet leadership to "re-install a revolutionary government" in Prague, Brezhnev concluded that abstaining from or voting against intervention would risk growing turmoil domestically and within the Eastern Bloc.

Consequently, Brezhnev ordered the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August, leading to Dubček's removal. Following the intervention, Brezhnev met with Czechoslovak reformer Bohumil Šimon, a member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and reportedly stated, "If I had not voted for Soviet armed assistance to Czechoslovakia you would not be sitting here today, but quite possibly I wouldn't either." Contrary to Moscow's intention of stabilizing the Eastern Bloc, the invasion catalyzed further dissent throughout the region.

In the aftermath of the Prague Spring's suppression, Brezhnev publicly declared that the Soviet Union reserved the right to interfere in the internal affairs of its satellite states to "safeguard socialism." This assertion became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine, though it essentially reaffirmed existing Soviet policy, as demonstrated by Khrushchev's intervention in Hungary in 1956. Brezhnev reiterated the doctrine in a speech at the Fifth Congress of the Polish United Workers' Party on November 13, 1968:

:When forces that are hostile to socialism try to turn the development of some socialist country towards capitalism, it becomes not only a problem of the country concerned, but a common problem and concern of all socialist countries.

The term "socialism" in this context implied control by communist parties loyal to the Kremlin. This new policy heightened tensions not only within the Eastern Bloc but also with Asian communist states. By 1969, relations with other communist countries had deteriorated to such an extent that Brezhnev was unable to gather even five of the fourteen ruling communist parties for an international conference in Moscow. Following the failed conference, the Soviets concluded that "there was no leading center of the international communist movement." Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev eventually repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine in the late 1980s, accepting the peaceful overthrow of Soviet rule in all its satellite countries in Eastern Europe.

Later, in 1980-1981, a political crisis erupted in Poland with the emergence of the Solidarity movement. By the end of October, Solidarity boasted 3 million members, and by December, 9 million. A public opinion poll organized by the Polish government indicated that 89% of respondents supported Solidarity. With the Polish leadership divided, the majority opposed imposing martial law, as suggested by Wojciech Jaruzelski. The Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc states were uncertain how to handle the situation, but Erich Honecker of East Germany pressed for military action. In a formal letter to Brezhnev, Honecker proposed a joint military intervention to control the escalating problems in Poland. A CIA report even suggested that the Soviet military was mobilizing for an invasion.

However, in a meeting of Eastern Bloc representatives at the Kremlin in 1980-1981, Brezhnev ultimately concluded on December 10, 1981, that it would be best to let Poland handle its domestic matters, reassuring Polish delegates that the USSR would only intervene if explicitly requested. This decision effectively marked the end of the Brezhnev Doctrine. Despite the absence of a Soviet military intervention, Wojciech Jaruzelski eventually acceded to Moscow's demands by imposing a "state of war," the Polish equivalent of martial law, on December 13, 1981.

4.2.2. The Vietnam War

Under Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union initially supported North Vietnam out of "fraternal solidarity." However, as the Vietnam War escalated, Khrushchev urged the North Vietnamese leadership to abandon the goal of liberating South Vietnam. He rejected an offer of assistance from the North Vietnamese government, instead advising them to engage in negotiations within the United Nations Security Council. After Khrushchev's ouster, Brezhnev resumed providing aid to the communist resistance in Vietnam. In February 1965, Premier Kosygin visited Hanoi accompanied by a dozen Soviet air force generals and economic experts. Throughout the war, Brezhnev's regime would ultimately ship 450.00 M USD worth of arms annually to North Vietnam.

Lyndon B. Johnson privately proposed to Brezhnev that the U.S. would guarantee an end to South Vietnamese hostility if Brezhnev would ensure a similar cessation from North Vietnam. Brezhnev initially showed interest but rejected the offer after Andrei Gromyko informed him that the North Vietnamese were not interested in a diplomatic resolution to the war. The Johnson administration responded by escalating the American presence in Vietnam but later invited the USSR to negotiate an arms control treaty. The USSR did not initially respond, partly due to a power struggle between Brezhnev and Kosygin over who had the right to represent Soviet interests abroad, and later due to the escalation of the "dirty war" in Vietnam.

In early 1967, Johnson offered a deal to Ho Chi Minh, proposing to end U.S. bombing raids in North Vietnam if Ho would cease infiltration into South Vietnam. U.S. bombing briefly halted, and Kosygin publicly supported this offer. However, the North Vietnamese government failed to respond, leading the U.S. to resume its raids. Following this, Brezhnev concluded that diplomatic solutions to the Vietnam War were futile. Later in 1968, Johnson invited Kosygin to the United States for the Glassboro Summit to discuss ongoing problems in Vietnam and the arms race. The summit was marked by a friendly atmosphere, but no concrete breakthroughs were achieved by either side.

In the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet border conflict, China continued to aid the North Vietnamese regime. However, with the death of Ho Chi Minh in 1969, China's strongest link to North Vietnam was severed. Meanwhile, Richard Nixon had been elected U.S. President. Despite his prior anti-communist rhetoric, Nixon stated in 1971 that the U.S. "must have relations with Communist China." His plan involved a slow withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Vietnam while still preserving the South Vietnamese government, which he believed was only possible by improving relations with both Communist China and the USSR. He later visited Moscow to negotiate treaties on arms control and the Vietnam War, though no agreement was reached on Vietnam. Ultimately, years of Soviet military aid to North Vietnam contributed to collapsing morale among U.S. forces, compelling their complete withdrawal from South Vietnam by 1973, paving the way for the country's unification under communist rule two years later.

4.2.3. Sino-Soviet Relations

Soviet foreign relations with the People's Republic of China rapidly deteriorated following Nikita Khrushchev's attempts to achieve a rapprochement with more liberal Eastern European states, such as Yugoslavia, and with the West. When Brezhnev consolidated his power base in the 1960s, China was engulfed in the crisis of Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, which decimated the Chinese Communist Party and other ruling bodies. Brezhnev, a pragmatic politician who promoted "stabilization," reportedly struggled to comprehend Mao's "self-destructive" drive to complete the socialist revolution.

However, Brezhnev soon faced his own challenges in Czechoslovakia, whose sharp deviation from the Soviet model prompted him and the rest of the Warsaw Pact to invade their Eastern Bloc ally. In the aftermath of the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, which involved the overthrow of the reformist government, the Soviet leadership proclaimed the Brezhnev Doctrine. This doctrine asserted that any threat to "socialist rule" in any state of the Soviet Bloc in Central and Eastern Europe was a threat to all of them, justifying intervention by fellow socialist states to forcibly remove the threat. The references to "socialism" specifically meant control by communist parties loyal to the Kremlin. This new policy exacerbated tensions not only within the Eastern Bloc but also with Asian communist states. By 1969, relations with other communist countries had deteriorated to a point where Brezhnev could not even gather five of the fourteen ruling communist parties to attend an international conference in Moscow. Following the failed conference, the Soviets concluded that "there was no leading center of the international communist movement." Mikhail Gorbachev later repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine in the late 1980s, as the Kremlin accepted the peaceful overthrow of Soviet rule in all its satellite countries in Eastern Europe.

Later in 1969, the deterioration in bilateral relations culminated in the Sino-Soviet border conflict. The Sino-Soviet split had deeply troubled Premier Alexei Kosygin, who for a while refused to accept its irrevocability. He briefly visited Beijing in 1969 amidst rising tensions between the USSR and China. By the early 1980s, both Chinese and Soviet officials began issuing statements calling for a normalization of relations between the two states. China's conditions for normalization included a reduction of Soviet military presence along the Sino-Soviet border, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan and the Mongolian People's Republic, and an end to Soviet support for the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia. Brezhnev responded in his March 1982 speech in Tashkent, calling for the normalization of relations. However, full Sino-Soviet normalization would take years, eventually being achieved under the last Soviet ruler, Mikhail Gorbachev.

4.2.4. Détente with the United States

During his eighteen years as leader of the USSR, Brezhnev's signature foreign policy innovation was the promotion of détente. While sharing some similarities with approaches pursued during the Khrushchev Thaw, Brezhnev's policy differed significantly in two ways. Firstly, it was more comprehensive and wide-ranging in its aims, including agreements on arms control, crisis prevention, East-West trade, European security, and human rights. Secondly, the policy emphasized the importance of equalizing the military strength of the United States and the Soviet Union. Defense spending under Brezhnev between 1965 and 1970 increased by 40%, with annual increases continuing thereafter. By 1982, the year of Brezhnev's death, 12% of the Soviet GNP was allocated to the military. Under Brezhnev, the Soviet Union's military budget increased eightfold, leading to the largest number of ICBMs, nuclear warheads, aircraft, tanks, and conventional forces globally. This military buildup led numerous observers, including Western ones, to argue that by the mid-1970s, the USSR had surpassed the United States to become the world's strongest military power.

At the 1972 Moscow Summit, Brezhnev and U.S. President Richard Nixon signed the SALT I Treaty. The first part of this agreement set limits on each side's development of nuclear missiles. The second part, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, prohibited both countries from designing systems to intercept incoming missiles, ensuring that neither the U.S. nor the Soviet Union would be emboldened to strike the other without fear of nuclear retaliation.

By the mid-1970s, Henry Kissinger's policy of détente towards the Soviet Union began to falter. Détente had rested on the assumption that some "linkage" could be found between the two countries, with the U.S. hoping that the signing of SALT I and an increase in Soviet-U.S. trade would halt the aggressive spread of communism in the Third World. This did not happen, as evidenced by Brezhnev's continued military support for the communist guerrillas fighting against the U.S. during the Vietnam War.

After Gerald Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter, American foreign policy became more overtly aggressive in its rhetoric towards the Soviet Union and the communist world. Attempts were also made to cease funding for repressive anti-communist governments and organizations supported by the United States. While initially advocating for a decrease in all defense initiatives, the later years of Carter's presidency saw an increase in U.S. military spending. When Brezhnev authorized the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Carter, following the advice of his National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, denounced the intervention as the "most serious danger to peace since 1945." The U.S. responded by halting all grain exports to the Soviet Union and boycotting the 1980 Summer Olympics held in Moscow. The Soviet Union retaliated by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics held in Los Angeles.

During Brezhnev's rule, the Soviet Union reached the peak of its political and strategic power relative to the United States. As a result of the limits agreed upon by both superpowers in the first SALT Treaty, the Soviet Union achieved nuclear weapons parity with the United States for the first time in the Cold War. Additionally, through negotiations during the Helsinki Accords, Brezhnev successfully secured the legitimization of Soviet hegemony over Central and Eastern Europe.

4.2.5. Intervention in Afghanistan

After the communist Saur Revolution in Afghanistan in 1978, the authoritarian actions imposed by the new Communist regime led to the Afghan Civil War, with the mujahideen leading a popular backlash. The Soviet Union grew concerned about losing influence in Soviet Central Asia. After a KGB report claimed that Afghanistan could be taken in a matter of weeks, Brezhnev and several top party officials agreed to a full intervention.

Contemporary researchers tend to believe that Brezhnev was misinformed about the situation in Afghanistan. His health had significantly decayed, and proponents of direct military intervention gained influence within the Politburo by allegedly using falsified evidence and suppressing dissenting opinions. They advocated for a relatively moderate scenario, maintaining a cadre of 1,500 to 2,500 Soviet military advisers and technicians already present in large numbers since the 1950s, but disagreed on sending hundreds of thousands of regular army units. Some sources suggest that Brezhnev's signature on the decree was obtained without him being fully informed, implying he would never have approved such a decision otherwise. Soviet ambassador to the U.S., Anatoly Dobrynin, believed that the true mastermind behind the invasion, who misinformed Brezhnev, was Mikhail Suslov. Brezhnev's personal physician, Mikhail Kosarev, later recalled that Brezhnev, when fully lucid, had in fact resisted full-scale intervention. Deputy Chairman of the State Duma, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, stated officially that despite some military support for the solution, hardline Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov was the only Politburo member who insisted on sending regular army units. Parts of the Soviet military establishment were opposed to any active Soviet military presence in Afghanistan, believing the Soviet Union should avoid involvement in Afghan politics.

The decision to intervene in Afghanistan in December 1979 proved to be a final and ultimately fatal legacy for Brezhnev's successors. This intervention effectively ended détente, leading to economic sanctions from the United States (such as the grain embargo) and a boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Coupled with the fall in oil prices in 1986 due to increased Saudi Arabian production, the massive military spending in Afghanistan rapidly exacerbated the Soviet Union's existing economic problems. This substantial economic burden in the arms race with the U.S., which began under Carter and accelerated under Ronald Reagan, contributed to the USSR's severe economic deterioration, paving the way for Mikhail Gorbachev's Perestroika reforms and the eventual dissolution of the Soviet Union. Furthermore, the invasion drew widespread international condemnation from Western, Chinese, and Islamic nations.

4.2.6. Support for Communist Movements

Brezhnev's policy of supporting communist movements and allied regimes globally significantly expanded Soviet influence in various regions. This included providing substantial military and economic aid to North Vietnam throughout the Vietnam War. Following the Vietnamese unification, the Soviet Union supported Vietnam in its conflict with Democratic Kampuchea, which was backed by China and the U.S.

In Africa, the Soviet Union provided military and economic assistance to Angola during its civil war (1975-1979), supplying arms and advisers to the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and deploying Cuban forces as proxies. Similarly, during the Ogaden War (1977-1978) between Ethiopia and Somalia, the Soviet Union switched its support from Somalia to Ethiopia, providing massive military aid and technical assistance that enabled Ethiopia to defeat Somalia. This period saw the Soviet military's active global projection of power, with the navy, under Admiral Sergey Gorshkov, gaining a worldwide presence and acquiring warm-water ports in locations like Aden in South Yemen, Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam, and Tartus in Syria. These interventions and proxy wars in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, alongside Soviet military support for India in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 and preparations for troop deployment during the Yom Kippur War in 1973, underscored the Soviet Union's expanding reach and competition with the United States and China.

5. Cult of Personality

The later years of Brezhnev's rule were characterized by a rapidly growing cult of personality, which often appeared detached from his declining health and the country's mounting problems.

Brezhnev's widely known fondness for medals (he accumulated over 100) became a central feature of his personality cult. In December 1966, on his 60th birthday, he was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union, the state's highest honor. He received this award, which included the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star, three more times on subsequent birthdays. On his 70th birthday, he was granted the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union, the highest Soviet military honor, making him the first "political Marshal" since Stalin, despite having no battlefield command experience. This promotion caused dissatisfaction among professional military officers, though their continued power and prestige under his regime ensured their support. After receiving the Marshal rank, he reportedly attended an 18th Army Veterans meeting, arriving in a long coat and announcing, "Attention, the Marshal is coming!" He also controversially conferred upon himself the rare Order of Victory in 1978, which was posthumously revoked in 1989 for not meeting the stringent criteria for citation. A planned promotion to the rank of Generalissimo of the Soviet Union for his seventy-fifth birthday was quietly shelved due to his ongoing health issues.

Brezhnev's desire for undeserved glory was further evidenced by his poorly written memoirs, which recalled his military service during World War II. These memoirs treated the relatively minor battles near Novorossiysk, such as the Malaya Zemlya operation, as a decisive military theater. Despite the book's obvious weaknesses, it was awarded the prestigious Lenin Prize for Literature and widely acclaimed by the Soviet press. This book was followed by two other volumes, one on the Virgin Lands Campaign and another on post-war industrial reconstruction in Ukraine. These works were translated into two dozen languages and, at least in official media, were mandatory reading in Soviet schools, though they are now believed to have been ghostwritten by his aides. The Malaya Zemlya period was further glorified with a film and a song by Aleksandra Pakhmutova.

However, unlike Stalin's cult of personality, which was enforced through terror, Brezhnev's cult was largely perceived by the populace as hollow, trite, and even a source of ridicule, as there were no purges to compel genuine respect or fear. It is unclear whether Brezhnev was aware of this widespread apathy, as he was often preoccupied with international summits, such as the SALT II treaty signed with Jimmy Carter in June 1979, and largely delegated significant domestic issues to his subordinates. Some of these subordinates, like agricultural head Mikhail Gorbachev, gradually came to believe that fundamental reforms were necessary. Despite this, there was no internal Politburo plot against Brezhnev, and he was allowed to gradually withdraw from power as his health declined. His deteriorating health was rarely, if ever, mentioned in the Soviet press, but it became increasingly evident through his absence from public events and the worsening economic and political situation.

Brezhnev's vanity also made him the subject of many Russian political jokes. Nikolai Podgorny reportedly warned him about this, but Brezhnev replied, "If they are poking fun at me, it means they like me."

6. Personal Life and Characteristics

Leonid Brezhnev's personal life was marked by declining health, family controversies, and distinctive personality traits, all of which increasingly influenced his public image and leadership.

6.1. Health Issues

Brezhnev's personality cult grew at a time when his health was in rapid decline. His physical condition began to deteriorate significantly from the mid-1970s. He had been a heavy smoker until the 1970s, developed an addiction to sleeping pills and tranquilizers, and began drinking excessively. His niece, Lyubov Brezhneva, attributed his dependencies and overall decline partly to severe depression stemming from the stresses of his position, the general state of the country, and an extremely unhappy family life marked by near-daily conflicts with his wife and children, particularly his troubled daughter Galina Brezhneva, whose erratic behavior, failed marriages, and involvement in corruption took a heavy toll on Brezhnev's mental and physical well-being. Brezhnev reportedly considered divorcing his wife and disowning his children multiple times, but interventions from his extended family and the Politburo, fearing negative publicity, dissuaded him.

Over the years, Brezhnev became overweight. From 1973 until his death, his central nervous system underwent chronic deterioration, and he suffered several minor strokes and insomnia. In 1975, he experienced his first heart attack. When receiving the Order of Lenin, Brezhnev was observed walking shakily and fumbling his words. According to American intelligence experts, U.S. officials had known for several years that Brezhnev suffered from severe arteriosclerosis and suspected other unspecified ailments. In 1977, American intelligence officials publicly suggested that Brezhnev also suffered from gout, leukemia, and emphysema from decades of heavy smoking, as well as chronic bronchitis. He was reportedly fitted with a pacemaker to manage heart rhythm abnormalities. On occasion, he experienced memory loss and speech problems and had difficulties with coordination. The Washington Post reported that "All of this is also reported to be taking its toll on Brezhnev's mood. He is said to be depressed, despondent over his own failing health and discouraged by the death of many of his long-time colleagues. To help, he has turned to regular counseling and hypnosis by an Assyrian woman, a sort of modern-day Rasputin."

Nursultan Nazarbayev recalled an incident in Alma-Ata (now Almaty) during a reception for Brezhnev at the Auezov Theater. About a thousand guests had gathered. After they were seated, Dinmukhamed Kunaev proposed a toast to Brezhnev. However, as soon as guests raised their glasses, Brezhnev unexpectedly stood up and headed toward the exit, prompting the entire republican leadership to follow him. Brezhnev walked outside, approached his car, and within a minute, the motorcade departed. Nazarbayev noted that it was evident Brezhnev had forgotten the purpose of his visit, but those around him pretended not to notice his frail state.

Upon suffering a stroke in 1975, Brezhnev's ability to lead the Soviet Union was significantly compromised. As his capacity to define Soviet foreign policy weakened, he increasingly deferred to a hardline brain trust comprising KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, longtime foreign minister Andrei Gromyko, and Defense Minister Andrei Grechko (succeeded by Dmitriy Ustinov in 1976). The Ministry of Health ensured doctors were constantly by Brezhnev's side, reviving him from near-death on several occasions. At this point, most senior CPSU officers desired to keep Brezhnev alive. Despite growing frustration with his policies, no one in the regime wanted to risk a new period of domestic turmoil that his death might cause. Western commentators began speculating on Brezhnev's heir apparent, with notable candidates including the older Mikhail Suslov and Andrei Kirilenko, and the younger Fyodor Kulakov and Konstantin Chernenko; Kulakov died of natural causes in 1978.

6.2. Family and Scandals

Brezhnev was married to Viktoria Denisova (1908-1995). They had a daughter, Galina (1929-1998), and a son, Yuri (born 1933). His niece, Lyubov Brezhneva, published a memoir in 1995 claiming that Brezhnev systematically used his position to secure privileges for his family, including appointments, apartments, access to private luxury stores, private medical facilities, and immunity from prosecution. Brezhnev resided in an apartment at 26 Kutuzovsky Prospekt in Moscow, the same building where Mikhail Suslov and Yuri Andropov lived. During holidays, he stayed at his Gosdacha in Zavidovo.

His family was involved in numerous corruption scandals that strained his public image and the integrity of the regime. His daughter Galina was known for her erratic behavior, failed marriages, and involvement in various high-profile corruption cases. Her extravagant lifestyle and association with criminals, including diamond smuggling, caused significant embarrassment to Brezhnev and the Party. Galina's husband, Yuri Churbanov, who rose to become First Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs, was implicated in the Uzbek cotton scandal. This massive corruption scheme involved falsifying cotton harvest statistics and engaging in widespread bribery and illicit enrichment within the Uzbek SSR, often in collusion with Uzbek Communist Party First Secretary Sharof Rashidov. Brezhnev's son, Yuri, a First Deputy Minister of Foreign Trade, also faced investigation by the KGB on suspicion of embezzlement.

These family scandals were largely suppressed by Brezhnev's long-serving ideologue and close aide, Mikhail Suslov. However, after Suslov's death in January 1982, the concealment became unsustainable. Yuri Andropov, who succeeded Suslov as the ideology secretary and had served as KGB chairman under Brezhnev, could no longer overlook the corruption. Upon becoming the supreme leader after Brezhnev's death, Andropov swiftly launched an anti-corruption campaign, leading to the arrest and prosecution of many of Brezhnev's relatives and associates, including Churbanov.

6.3. Personality Traits and Hobbies

Initially, Brezhnev adopted a team-player approach to leadership, consulting widely with his colleagues and being open to their opinions, a stark contrast to Khrushchev's more volatile style. However, as his power consolidated, his personal demeanor began to reflect a growing vanity and a desire for ceremonial authority.

Brezhnev's main passion was driving luxury foreign cars, which he frequently received as gifts from heads of state worldwide. He often drove these vehicles between his dacha and the Kremlin, reportedly with "flagrant disregard for public safety." During a 1973 summit with Richard Nixon in the United States, Brezhnev expressed a desire to drive around Washington in a Lincoln Continental Nixon had just gifted him. When informed that the United States Secret Service would not permit this, he humorously responded, "I will take the flag off the car, put on dark glasses, so they can't see my eyebrows and drive like any American would," to which Henry Kissinger famously retorted, "I have driven with you and I don't think you drive like an American!"

His vanity and the disconnect between his public image and the reality of Soviet society became the subject of numerous Russian political jokes. Nikolai Podgorny reportedly warned him about this, but Brezhnev replied, "If they are poking fun at me, it means they like me."

7. Death and State Funeral

Leonid Brezhnev's death marked the end of an era, shrouded by political maneuvering among his potential successors and followed by an elaborate state funeral.

Brezhnev's health significantly worsened in the winter of 1981-1982. While the Politburo contemplated his succession, all signs indicated the ailing leader was nearing his end. The choice of successor would have been heavily influenced by Mikhail Suslov, the powerful Party ideologue, but he died at the age of 79 in January 1982. Yuri Andropov subsequently took Suslov's seat in the Central Committee Secretariat. By May, it became evident that Andropov was making a bid for the office of General Secretary. With the assistance of his KGB associates, Andropov began circulating rumors that political corruption had intensified during Brezhnev's tenure, aiming to create an environment hostile to Brezhnev within the Politburo. Andropov's actions demonstrated a lack of fear of Brezhnev's potential wrath.

In March 1982, Brezhnev suffered a concussion and fractured his right clavicle during a factory tour in Tashkent, when a metal balustrade collapsed under the weight of several factory workers, falling on him and his security detail. This incident was reported in Western media as a stroke. After a month-long recovery, Brezhnev worked intermittently through November. On November 7, 1982, he made his final public appearance, standing on Lenin's Mausoleum's balcony during the annual military parade and workers' demonstration commemorating the 65th anniversary of the October Revolution.

Three days later, on November 10, 1982, at 8:30 AM, Leonid Brezhnev died of a heart attack in Moscow at the age of 75. His death was announced worldwide via radio on November 11. A three-day period of nationwide mourning was declared. His body was laid in state in the Column Hall of the House of Unions in Moscow, where mourners paid their respects.

His state funeral was a grand and solemn affair, attended by national and international statesmen from around the globe, including Japanese Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki. His wife and family were also present. Brezhnev was dressed for burial in his Marshal's uniform, adorned with his numerous medals. His coffin was carried by an armored car to Red Square. At the center of Red Square, the open coffin was transferred to a red-draped platform facing Lenin's Mausoleum. Speeches were delivered from atop the mausoleum by Yuri Andropov, Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov, Russian Academy of Sciences President Anatoli Alexandrov, and a factory worker. Members of the Politburo, including Andropov, Konstantin Chernenko, and Andrei Gromyko on the left, and Premier Nikolai Tikhonov, Ustinov, and Moscow Party leader Viktor Grishin on the right, then served as pallbearers, carrying the coffin to the rear of the mausoleum. At exactly 12:45 PM, Brezhnev's coffin was lowered into his grave in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis, between the tombs of Felix Dzerzhinsky and Yakov Sverdlov, accompanied by the solemn sounds of a military band, sirens, and gun salutes.

A number of countries, including Cuba, Nicaragua, Mozambique, Afghanistan, and India, declared national mourning. The delay in the announcement of Brezhnev's death was reportedly due to power struggles within the Politburo regarding his succession. On the day he died, Soviet television stations canceled regular programming and broadcasted somber classical music and programs honoring Lenin's achievements and commemorating the Great Patriotic War, signaling to the public that a major Soviet leader had passed away. Initially, some speculated it was Andrei Kirilenko, who had not attended the recent parade and was expected to retire. However, the absence of Brezhnev's signature on a congratulatory telegram to Angola for its independence day, contrary to custom, increasingly suggested that Brezhnev himself had died. Andropov was subsequently appointed as his successor.

8. Legacy and Historical Assessment

Leonid Brezhnev's legacy remains complex and contested, reflecting a period of both perceived stability and undeniable stagnation that ultimately contributed to the Soviet Union's decline.

8.1. Positive Reappraisals

Brezhnev presided over the Soviet Union for a longer period than anyone except Joseph Stalin. He is sometimes remembered as a peacemaker and a common-sense statesman, particularly for his role in pursuing détente with the West. During his governance, the Soviet Union attained an unprecedented level of military and strategic power in relation to the United States. Through agreements like SALT I, the USSR achieved nuclear weapons parity with the U.S. for the first time. The Helsinki Accords also effectively legitimized Soviet hegemony over Central and Eastern Europe. Under his rule, the Soviet Union saw an expansion of its global influence, particularly in the Middle East and Africa, partly due to its significant military development.

In post-Soviet Russia, Brezhnev's rule has received consistently high approval ratings in public polls, often faring better than his predecessors and successors. A 1999 poll ranked him as the best Russian leader of the 20th century. In a 2007 poll by VTsIOM, a majority of Russians expressed a preference for living during the Brezhnev era over any other period of 20th-century Soviet history. A 2013 Levada Center poll indicated that Brezhnev was Russia's favorite 20th-century leader, with 56% approval, surpassing both Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. Another 2013 poll also voted him the best Russian leader of the 20th century. Even in Ukraine, a 2018 Rating Sociological Group poll found that 47% of respondents held a positive opinion of Brezhnev. These positive reappraisals often highlight the period's perceived stability, improved living standards (especially in the early years), and the Soviet Union's enhanced international prestige.

8.2. Criticisms and Controversies

Objectively, Brezhnev's leadership faces significant criticism for ushering in the "Era of Stagnation," a period during which fundamental economic problems were largely ignored, and the Soviet political system gradually declined. He is often blamed for failing to modernize the country and adapt to changing global dynamics. Critics argue that his conservative, pragmatic approach, while initially providing stability after the tumultuous Khrushchev years, ultimately stifled innovation and reform.

The reversal of Khrushchev's liberalization policies led to increased political repression and human rights abuses under Brezhnev, with the KGB regaining significant power and dissidents facing severe penalties, including forced psychiatric hospitalization. His personal vanity, characterized by an excessive collection of military awards and the publication of ghostwritten memoirs, further drew criticism and became the subject of numerous political jokes, undermining public respect for his leadership.

The costly Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in 1979 is widely regarded as one of the most significant and detrimental decisions of his career. This war not only severely undermined the Soviet Union's international standing but also placed immense strain on its already struggling internal economy, contributing to its eventual collapse. Furthermore, pervasive corruption, particularly involving his family members like his daughter Galina and son-in-law Yuri Churbanov (implicated in the Uzbek cotton scandal), eroded the regime's integrity and public trust. Overall, while Brezhnev's rule saw the Soviet Union reach its peak as a military superpower, critics argue that his reluctance to implement necessary reforms and his repressive domestic policies ultimately contributed to the systemic weaknesses that led to the Soviet Union's eventual dissolution.

9. Honors and Commemoration

Leonid Brezhnev received an extensive array of domestic and international awards and honors throughout his lifetime, reflecting the height of Soviet prestige and influence during his rule.

Domestically, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union four times, the title of Hero of Socialist Labour once, and the Order of Lenin eight times. He also received the Order of the October Revolution twice, the Order of the Red Banner twice, the Order of Bogdan Khmelnitsky Second Class, the Order of the Patriotic War First Class, and the Order of the Red Star. Among his other military and commemorative medals were the Medal "For Merit in Battle", the Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin", the Medal "For the Defence of Odessa", the Medal "For the Defence of the Caucasus", the Medal "For the Victory Over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945", and various jubilee medals marking anniversaries of the Great Patriotic War and the Soviet Armed Forces. He also received the Medal "For the Liberation of Warsaw", the Medal "For the Capture of Vienna", and the Medal "For the Liberation of Prague", highlighting his wartime service. His contributions to post-war reconstruction and development were recognized with the Medal "For the Restoration of the Black Metallurgy Enterprises of the South" and the Medal "For the Development of the Virgin Lands". For his literary works, including his controversial memoirs, he was awarded the Lenin Prize for Literature in 1979. He also received the International Lenin Peace Prize in 1972. In 1978, he was awarded the Order of Victory, a highly prestigious military order, though this award was posthumously revoked in 1989 due to non-compliance with the order's specific criteria.

Internationally, Brezhnev received numerous accolades from allied socialist states and other countries. He was named Hero of the People's Republic of Bulgaria three times and awarded the Order of Georgi Dimitrov three times. He was also a Hero of the German Democratic Republic three times and received the Order of Karl Marx three times. Mongolia honored him as a Hero of the Mongolian People's Republic and a Hero of Labor of the Mongolian People's Republic, alongside four Order of Sukhbaatars. Czechoslovakia bestowed upon him the title of Hero of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic three times and the Order of Klement Gottwald four times. Cuba named him a Hero of the Republic of Cuba and awarded him the Order of José Martí. From Vietnam, he received the title of Hero of Labor and the Ho Chi Minh Order. Other significant international honors included the Order of the Great Star of Yugoslavia, the Order of the White Rose of Finland, the Order of May from Argentina, the Order of the Sun of Peru, the Order of Polonia Restituta First Class from Poland (later revoked), the Order of the Star of the Socialist Republic of Romania, the Order of the National Flag First Class from North Korea, and the Order of the Star of Honor from Ethiopia.

Following his death, some places were renamed in his honor, although many of these changes were reversed during the period of de-Stalinization and perestroika. The automobile manufacturing city of Naberezhnye Chelny in the Tatarstan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was renamed "Brezhnev City" from 1982 until 1988. The first ship of the Arktika-class nuclear-powered icebreakers, the Arktika, was renamed Leonid Brezhnev in 1982 but reverted to its original name in 1988. The aircraft carrier that would later become Admiral Kuznetsov, laid down in 1982, was briefly named Leonid Brezhnev during its construction in 1983 before being renamed again. A district outside Moscow, Cheryomushky Rayon, was briefly renamed after him.