1. Overview

Ireland, officially also described as the Republic of Ireland, is a sovereign state in Northwestern Europe occupying about five-sixths of the island of Ireland. It is a country known for its rich history, vibrant culture, stunning landscapes, and complex political and social development. Geographically, it features rugged coastlines, inland plains, numerous rivers and lakes, and a temperate oceanic climate. Historically, Ireland has experienced periods of ancient civilizations, Viking and Norman invasions, centuries of English and later British rule, a tumultuous path to independence involving revolution and civil war, and significant socio-economic transformations in the modern era, including the "Celtic Tiger" boom and subsequent financial challenges.

The political system is a parliamentary constitutional republic with a President as head of state and a Taoiseach (Prime Minister) as head of government. The Oireachtas (National Parliament) is bicameral. Ireland maintains a policy of military neutrality and is an active member of international bodies such as the European Union and the United Nations, with a notable history of contributing to peacekeeping missions.

The Irish economy has evolved from a predominantly agricultural base to a modern, open economy with significant foreign direct investment, particularly in technology, pharmaceuticals, and financial services. However, this development has also brought challenges related to economic inequality and the social impacts of globalization and taxation policies.

Irish society is characterized by a dynamic demographic profile, including a history of emigration and recent immigration leading to a more multicultural landscape. The Irish language (Gaeilge) holds official status alongside English, with ongoing efforts for its revitalization. While traditionally a staunchly Catholic country, Ireland has seen significant secularization and social liberalization in recent decades, reflected in changes to laws concerning divorce, contraception, abortion, and LGBTQ+ rights. The nation places a strong emphasis on education, healthcare, and social welfare, though access and equity remain areas of ongoing public discourse.

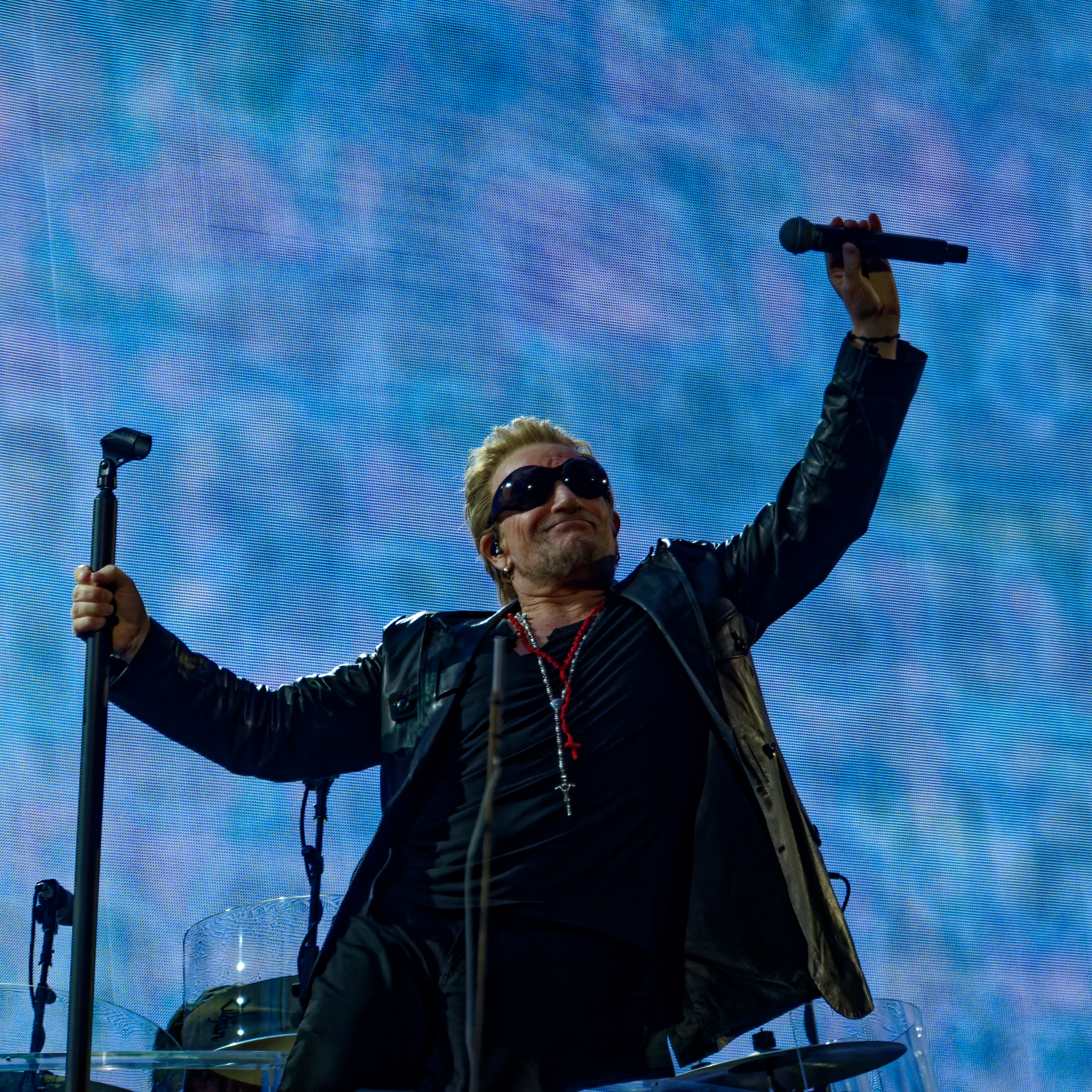

Culturally, Ireland has made substantial contributions to world literature, music, and dance, with a rich heritage of traditional arts alongside contemporary expressions. Its national symbols, cuisine, and sports are integral to its identity. This article seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of Ireland, reflecting a center-left/social liberalism perspective that emphasizes social impact, human rights, democratic development, and the welfare of minorities and vulnerable groups within its factual presentation.

2. Name

The state is officially named Ireland in English and Éire (ÉireˈeːɾʲəIrish) in the Irish language. Article 4 of the Constitution of Ireland, adopted in 1937, states: "The name of the State is Éire, or, in the English language, Ireland." The term Republic of Ireland (Poblacht na hÉireannPoblacht na hÉireannIrish) is the official "description" of the state, as declared by Republic of Ireland Act 1948, Section 2: "It is hereby declared that the description of the State shall be the Republic of Ireland." This act did not change the name of the state, as doing so would have required a constitutional amendment.

The Irish name Éire derives from Ériu, a goddess in Irish mythology. The state created in 1922, comprising 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland, was "styled and known as the Irish Free State" (Saorstát ÉireannSaorstát ÉireannIrish).

The government of the United Kingdom initially used the name "Eire" (without the diacritic) and, from 1949, "Republic of Ireland" to refer to the state. It was not until the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, when the Irish state relinquished its constitutional claim to Northern Ireland, that the British government began to use "Ireland" as the name for the state.

Informally, the state is also referred to as "the Republic", "Southern Ireland", or "the South", particularly when distinguishing it from the island of Ireland as a whole or when discussing Northern Ireland ("the North"). Irish republicans often reserve the name "Ireland" for the entire island and may refer to the state as "the Free State", "the 26 Counties", or "the South of Ireland" as a response to the partitionist view that Ireland stops at the border.

3. History

The history of the island of Ireland encompasses millennia of human settlement, cultural shifts, invasions, colonial rule, and the struggle for independence, shaping the modern Irish state.

3.1. Prehistory and Ancient Ireland

The earliest evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to the Mesolithic period, around 10,500 BC, with hunter-gatherer communities. The Neolithic period, beginning around 4000 BC, saw the introduction of agriculture, pottery, and the construction of megalithic monuments such as Newgrange (part of the Brú na Bóinne complex), Poulnabrone dolmen, and various stone circles. These structures indicate sophisticated societies with complex belief systems.

The Bronze Age (circa 2500 BC - 500 BC) brought metalworking, leading to new tools, weapons, and artistic expressions in gold. Society became more hierarchical. The Iron Age followed, characterized by the arrival of Celtic culture and language (Gaelic) around 500 BC. While the nature of the Celtic arrival-whether through mass migration or cultural diffusion-is debated, Celtic traditions, art (like the La Tène style), social structures (based on petty kingdoms or tuatha), and legal systems (Brehon law) became dominant. Ireland was never part of the Roman Empire, allowing its indigenous Celtic culture to develop relatively uninterrupted during this period. Ptolemy's map of Ireland from the 2nd century AD provides one of the earliest written accounts of the island's geography and tribes. Early Irish society was rural and decentralized, with a system of High Kings holding nominal authority over regional kings.

Christianity was introduced to Ireland gradually, traditionally associated with Saint Patrick in the 5th century AD. This led to the development of a unique monastic tradition that became a major center of learning and culture in Europe during the Early Middle Ages, preserving classical knowledge and producing renowned works of Insular art like the Book of Kells. These monasteries were often self-sufficient communities and played a crucial role in Irish society.

3.2. Viking and Norman Era

Beginning in the late 8th century (around 795 AD), Viking raids began along the Irish coast. Initially focused on plunder, especially of wealthy monasteries, the Vikings later established settlements and trading posts, including Dublin, Waterford, Wexford, Cork, and Limerick. These settlements became Ireland's first towns and integrated the island into wider European trade networks. The Vikings also influenced Irish warfare, shipbuilding, and art. Irish resistance to Viking incursions was fragmented but persistent. Brian Boru, High King of Ireland, is famously credited with defeating a major Viking force at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, though Viking influence and settlement continued.

The Norman era began in 1169 when a force of Cambro-Norman knights, at the invitation of the deposed King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, landed in Ireland. This was followed by a larger expedition led by Richard de Clare (Strongbow) and, in 1171, by King Henry II of England, who asserted his overlordship as Lord of Ireland. The Norman conquest led to profound changes: the introduction of feudalism, the construction of castles and walled towns, the establishment of a centralized (though initially limited) English administration in Dublin (the Lordship of Ireland), and the reorganization of the Church along continental European lines. While Norman lords carved out fiefdoms, Gaelic chieftains continued to resist, leading to a complex interplay of conflict and assimilation. Over time, many Norman families became "more Irish than the Irish themselves" (Hiberniores Hibernis ipsisHiberniores Hibernis ipsisLatin), adopting Gaelic language and customs, a phenomenon that concerned the English Crown.

3.3. English Rule and Colonial Period

English control over Ireland, initially incomplete after the Norman invasion, was gradually and often brutally extended over subsequent centuries. The Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366 attempted to prevent the assimilation of the Anglo-Norman settlers into Gaelic society by outlawing intermarriage, the Irish language, and Irish customs among the English colonists, reflecting the Crown's desire to maintain a distinct colonial identity and control. However, English authority largely remained confined to the area around Dublin known as the Pale.

The Tudor conquest in the 16th century marked a significant intensification of English efforts to subdue Ireland. This period saw brutal military campaigns, land confiscations, and the beginning of the plantation policy, whereby land was seized from Gaelic and rebellious Hiberno-Norman lords and granted to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland. The Reformation added a religious dimension to the conflict, as the English Crown attempted to impose Protestantism on a largely Catholic population. Rebellions, such as the Desmond Rebellions and the Nine Years' War led by Hugh O'Neill, were fiercely suppressed.

The 17th century witnessed further upheaval, including the Flight of the Earls in 1607, the Ulster Plantation, and the devastating Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639-1651), which included the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and the subsequent brutal Cromwellian conquest. This conquest led to widespread land confiscations, the transportation of Irish people as indentured servants to the Caribbean, and the establishment of a new Protestant landowning class. The Penal Laws, enacted primarily in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, systematically disadvantaged Irish Catholics (and to a lesser extent Protestant Dissenters) in land ownership, politics, law, and the military, cementing Protestant Ascendancy. Despite these measures, Catholic identity remained strong and became intertwined with Irish resistance.

The 18th century saw Ireland governed by a Protestant-dominated Parliament of Ireland, which, while asserting some legislative independence (notably in 1782), remained subordinate to the British Crown and Parliament. The ideals of the American and French Revolutions inspired movements for reform and independence, such as the United Irishmen, leading to the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which was ultimately suppressed. In response, the British government passed the Acts of Union 1800, abolishing the Irish Parliament and formally incorporating Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland on 1 January 1801.

3.4. Home Rule Movement, Revolution, and Independence

The 19th century under the Union was marked by significant social and political challenges, including the devastating Great Famine (An Gorta MórAn Gorta MórIrish, 1845-1849). Caused by potato blight, the Famine led to the deaths of about one million people and the emigration of another million, primarily to the United States, Canada, and Britain. The British government's response was widely criticized as inadequate, exacerbating the suffering and fueling resentment. The Famine had a profound and lasting impact on Irish demographics, society, and politics, intensifying calls for land reform and self-government.

The Home Rule movement, which sought legislative independence for Ireland within the United Kingdom, gained momentum in the latter half of the 19th century. Leaders like Daniel O'Connell (earlier in the century, campaigning for Catholic Emancipation, achieved in 1829) and later Charles Stewart Parnell mobilized mass support. The Irish Parliamentary Party under Parnell effectively used parliamentary tactics and agrarian agitation (like the Land War) to push for Home Rule and land reform. Several Home Rule Bills were defeated in the British Parliament, facing strong opposition from Unionists, particularly in Ulster, who feared Catholic-majority rule and economic disruption.

The early 20th century saw Home Rule become a central issue in British politics. The Third Home Rule Act was passed in 1914, but its implementation was suspended due to the outbreak of World War I. The delay and the growing militancy of both Nationalists (who formed the Irish Volunteers) and Unionists (who formed the Ulster Volunteers) brought Ireland to the brink of civil war.

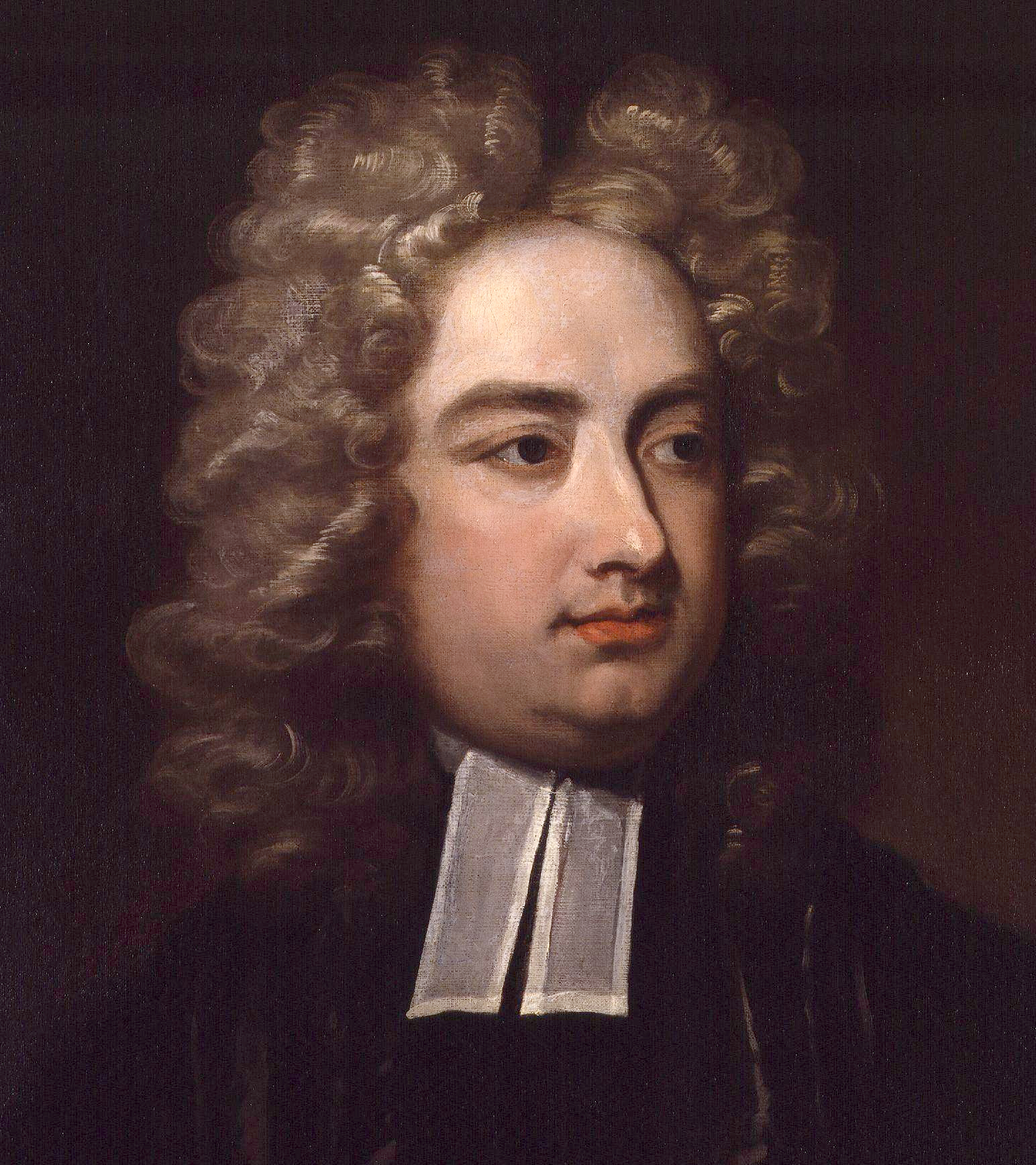

During World War I, a faction of radical nationalists, believing in "England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity," staged the Easter Rising in Dublin in April 1916. Led by figures like Patrick Pearse and James Connolly, the rebels proclaimed an Irish Republic. The Rising was quickly suppressed, and its leaders were executed. These executions, however, galvanized public opinion against British rule and in favor of the more radical Sinn Féin party, which advocated for complete independence.

In the 1918 general election, Sinn Féin won a landslide victory in Ireland. Its elected members refused to take their seats in the British Parliament, instead establishing an independent Irish parliament, Dáil Éireann, in January 1919, and reaffirmed the 1916 Proclamation of an Irish Republic. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), a guerrilla conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces, including the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, known for their brutality.

The war ended with a truce in July 1921, followed by the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. The Treaty provided for the establishment of the Irish Free State (Saorstát ÉireannSaorstát ÉireannIrish) as a Dominion within the British Commonwealth, covering 26 of Ireland's 32 counties. The remaining six counties of Northern Ireland, which had a Unionist majority, opted to remain part of the United Kingdom, leading to the partition of Ireland. The Treaty was highly controversial in Ireland, particularly the Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch required of members of the Dáil.

3.5. Irish Civil War

The Anglo-Irish Treaty's acceptance by a narrow majority in Dáil Éireann led directly to the Irish Civil War (June 1922 - May 1923). The conflict was fought between the forces of the newly established Irish Free State (the National Army, or pro-Treaty forces), led by figures such as Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith, and the anti-Treaty IRA, who saw the Treaty as a betrayal of the Irish Republic proclaimed in 1919. The anti-Treaty side, led politically by Éamon de Valera (who had opposed the Treaty), objected to the Free State's Dominion status, the Oath of Allegiance, and the partition of Ireland.

The Civil War was a bitter and divisive conflict, characterized by assassinations, executions, and atrocities on both sides. Key figures, including Michael Collins, were killed. The pro-Treaty forces, supported by the British government with arms and equipment, ultimately prevailed due to superior resources and a more organized military structure. The anti-Treaty IRA, often referred to as "Irregulars," lacked widespread public support for continued warfare and an effective command structure. The war ended in May 1923 when the anti-Treaty leadership ordered a ceasefire and dumped arms, though no formal surrender occurred.

The Civil War had a devastating impact on the nascent Irish state, leaving a legacy of political bitterness that shaped Irish politics for decades. The two main political parties that dominated Irish politics for much of the 20th century, Fine Gael (descended from the pro-Treaty side) and Fianna Fáil (founded by de Valera and emerging from the anti-Treaty side), originated from this conflict. The war resulted in significant loss of life and economic disruption, further compounding the challenges faced by the newly independent state. The human cost and the brutal tactics employed by both sides left deep scars on Irish society.

3.6. Irish Free State and Constitution of 1937

The Irish Free State (Saorstát ÉireannSaorstát ÉireannIrish) officially came into existence on December 6, 1922, based on the Anglo-Irish Treaty and its own Constitution of the Irish Free State. W. T. Cosgrave of Cumann na nGaedheal (the pro-Treaty party) became the first President of the Executive Council (head of government). The early years of the Free State were focused on establishing state institutions, restoring law and order after the Civil War, and rebuilding the economy. The government pursued conservative social and economic policies.

Under the Statute of Westminster 1931, the Free State, along with other British Dominions, gained greater legislative autonomy from the United Kingdom. Éamon de Valera and his Fianna Fáil party came to power in 1932 and began to dismantle many of the remaining constitutional links with Britain. This included abolishing the Oath of Allegiance and the office of Governor-General.

In 1937, a new constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann (Bunreacht na hÉireannBunreacht na hÉireannIrish), was adopted by plebiscite, coming into force on December 29, 1937. This constitution replaced the Irish Free State with a new state named Éire (or Ireland in English). It established the office of President of Ireland as head of state, though the state did not formally become a republic at this point, as the British monarch still retained some external functions related to foreign affairs under the Executive Authority (External Relations) Act 1936. Articles 2 and 3 of the 1937 Constitution asserted a territorial claim over the entire island of Ireland, which became a point of contention with the United Kingdom and Unionists in Northern Ireland. The 1937 Constitution also reflected the predominantly Catholic ethos of the state at the time, with special recognition given to the Catholic Church, though it also guaranteed religious freedom. It represented a significant step towards full sovereignty and a republican form of government.

3.7. Proclamation of the Republic and Modern History

Ireland remained officially neutral during World War II, a period known domestically as The Emergency (Ré na PráinneRé na PráinneIrish). This policy, pursued by Taoiseach Éamon de Valera, was aimed at asserting Irish sovereignty and avoiding entanglement in a major European conflict, though it was controversial, particularly with Britain. Despite official neutrality, many Irish citizens served in the Allied forces.

In 1948, The Republic of Ireland Act 1948 was passed by the Oireachtas. This Act declared that the description of the State would be the "Republic of Ireland" and transferred the remaining statutory functions of the British monarch in relation to external affairs to the President of Ireland. The Act came into effect on Easter Monday, April 18, 1949, formally establishing Ireland as a republic and leading to its departure from the British Commonwealth.

Post-war Ireland faced economic stagnation and high emigration for several decades. However, significant economic and social changes began in the latter half of the 20th century. Ireland joined the United Nations in 1955 and the European Communities (EC), the precursor to the European Union (EU), in 1973. EC/EU membership had a profound impact, providing access to new markets, agricultural subsidies, and structural funds, which contributed to economic modernization.

The late 1980s and particularly the 1990s saw a period of unprecedented economic growth known as the Celtic Tiger. This was fueled by foreign direct investment (attracted by low corporation tax and an educated, English-speaking workforce), EU membership, social partnership agreements, and investment in education and technology. This boom led to increased prosperity, a reversal of emigration trends, and significant societal changes. However, the Celtic Tiger period ended with the global financial crisis of 2008, which severely impacted Ireland due to a property bubble burst and a banking crisis, leading to an EU/IMF bailout and a period of austerity. The economy has since recovered, experiencing strong growth from around 2014.

A major political development was the Northern Ireland peace process. The Troubles, a period of sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland lasting from the late 1960s to 1998, saw significant involvement from the Irish government in seeking a peaceful resolution. The Good Friday Agreement (or Belfast Agreement) of 1998, overwhelmingly approved in referendums in both parts of Ireland, established power-sharing institutions in Northern Ireland and cross-border bodies. As part of the agreement, Ireland amended its constitution to remove the territorial claim to Northern Ireland, replacing it with an aspiration for peaceful unity by consent.

Socially, Ireland has undergone significant liberalization. Referendums have led to the legalization of divorce (1995), same-sex marriage (2015), and the repeal of the constitutional ban on abortion (2018), reflecting a decline in the influence of the Catholic Church and evolving societal values concerning human rights and individual autonomy. Issues such as housing shortages and healthcare capacity remain significant contemporary challenges.

4. Geography

Ireland is an island in Northwestern Europe, separated from Great Britain by the Irish Sea and the North Channel. The Republic of Ireland occupies approximately five-sixths of the island's total area. Its only land border is with Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom. The country is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, with the Celtic Sea to the south and St George's Channel to the southeast. The geography is characterized by a central plain surrounded by coastal mountains, numerous rivers, lakes, and an indented coastline.

4.1. Topography and Geology

The island of Ireland has a varied topography. A large central lowland of limestone, covered with glacial deposits of clay and sand, is ringed by coastal mountains. The main mountain ranges include the MacGillycuddy's Reeks in the southwest, which contains Ireland's highest peak, Carrauntoohil (3.4 K ft (1.04 K m)); the Wicklow Mountains in the east; the Twelve Bens and Maumturks in Connemara (west); and the mountains of Donegal in the northwest. The central plain is relatively flat and is drained by several major rivers, including the River Shannon, which at 224 mile (360.5 km) is the longest river in Ireland and Great Britain. It flows through large lakes such as Lough Ree and Lough Derg. Other significant rivers include the River Liffey (flowing through Dublin), the River Boyne, the River Suir, the River Nore, and the River Barrow. Ireland also has numerous lakes (loughs), with Lough Neagh (mostly in Northern Ireland) being the largest in the British Isles, and Lough Corrib being the largest in the Republic.

The coastline is heavily indented, particularly in the west and southwest, featuring numerous headlands, bays, and peninsulas such as the Dingle Peninsula and the Iveragh Peninsula. Notable coastal features include the Cliffs of Moher in County Clare and the Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland. There are many islands off the coast, the largest being Achill Island.

Geologically, Ireland's rocks are diverse, reflecting a complex geological history. The oldest rocks date back to the Precambrian. Much of the central plain is composed of Carboniferous limestone, which has given rise to karst landscapes in areas like The Burren in County Clare. The mountain ranges are generally formed from older, harder rocks such as sandstone, quartzite, and granite. The island's landscape was significantly shaped by glaciation during the last ice age, which created features like U-shaped valleys, corries, and drumlins. Extensive boglands, particularly blanket bog and raised bog, are a characteristic feature of the Irish landscape, formed in poorly drained areas after the retreat of the ice.

4.2. Climate

Ireland has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), significantly influenced by the Atlantic Ocean and the warming effect of the North Atlantic Drift, an extension of the Gulf Stream. This results in mild winters and cool summers, with a narrow annual temperature range.

Average temperatures are generally between 39.2 °F (4 °C) and 44.6 °F (7 °C) in January and February, the coldest months, and between 57.2 °F (14 °C) and 60.8 °F (16 °C) in July and August, the warmest months. Temperatures seldom fall below 23 °F (-5 °C) in winter or rise above 78.8 °F (26 °C) in summer. The highest recorded temperature was 91.94 °F (33.3 °C) at Kilkenny Castle on 26 June 1887, and the lowest was -2.3800000000000026 °F (-19.1 °C) at Markree Castle, County Sligo, on 16 January 1881.

Rainfall is a frequent occurrence throughout the year, though it varies regionally. The west and northwest coasts receive the highest rainfall, often exceeding 0.1 K in (2.00 K mm) annually, due to prevailing southwesterly winds from the Atlantic. The east coast, particularly the Dublin area, is considerably drier, with average annual rainfall around 30 in (750 mm). Snowfall is relatively uncommon, especially at lower altitudes, though it can occur in winter, particularly on higher ground.

Sunshine duration varies, with the southeast coast receiving the most sunshine, averaging over 7 hours a day in early summer. The north and west are generally cloudier. The far north and west are among the windiest regions in Europe, offering significant potential for wind energy generation. Overall, the climate is characterized by its changeability, with weather conditions often shifting rapidly.

4.3. Flora and Fauna

Ireland's flora and fauna, while less diverse than that of mainland Europe or Great Britain due to its island nature and earlier separation after the last ice age, possess unique characteristics.

Historically, Ireland was heavily forested with native deciduous trees such as oak, ash, birch, alder, hazel, and elm, along with evergreen trees like Scots pine and yew. Extensive deforestation for agriculture and timber, starting from the Neolithic period and accelerating in later centuries, particularly during English rule for shipbuilding and fuel, dramatically reduced this forest cover. Today, woodland covers about 10-11% of Ireland, much of which consists of non-native conifer plantations. Efforts are underway to increase native woodland coverage. Hedgerows are a significant feature of the agricultural landscape, providing important habitats for many species. Boglands (peatlands) cover a substantial area and support specialized flora like Sphagnum moss, heathers, and sundews. Notable flowering plants include the strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), found in the southwest, and various species of orchids and wildflowers in The Burren.

Ireland's native land mammal fauna is relatively limited. Species include the red fox, badger, Irish hare, stoat, red deer (Ireland's largest native land mammal), and several species of bats. The pine marten, once rare, has seen a recovery. There are no native snakes in Ireland, a fact often attributed in folklore to Saint Patrick. The only native land reptile is the viviparous lizard. Amphibians include the common frog, smooth newt, and the natterjack toad (found in specific coastal areas).

The island is rich in birdlife, particularly seabirds along its extensive coastline, including puffins, gannets, guillemots, and kittiwakes. Inland and freshwater birds are also diverse. Ireland is an important location for migratory birds, including whooper swans and Brent geese that overwinter.

Freshwater fish include salmon, trout, pike, and eel. The marine life around Ireland's coast is rich, benefiting from the relatively unpolluted waters of the Atlantic.

Conservation efforts are ongoing to protect Ireland's biodiversity, with several national parks and nature reserves established. However, pressures from agriculture, habitat fragmentation, invasive species, and climate change continue to pose challenges.

4.4. National Parks

Ireland has six National Parks, managed by the National Parks & Wildlife Service, which are designated for their significant natural beauty, ecological importance, and recreational value. These parks play a crucial role in the conservation of native flora, fauna, and habitats, as well as providing opportunities for public enjoyment and education about the natural environment.

The six National Parks are:

1. Killarney National Park (Páirc Náisiúnta Chill AirnePáirc Náisiúnta Chill AirneIrish), County Kerry: Established in 1932, this was Ireland's first national park. It covers over 39 mile2 (102 km2) of diverse ecology, including the world-famous Lakes of Killarney, extensive oak and yew woodlands (some of the largest remaining native woodlands in Ireland), and mountains like Mangerton and Torc. It is home to Ireland's only native herd of Red Deer. The park is also a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

2. Glenveagh National Park (Páirc Náisiúnta Ghleann BheathaPáirc Náisiúnta Ghleann BheathaIrish), County Donegal: Located in the northwest, this park encompasses 66 mile2 (170 km2) of rugged mountains, pristine lakes, waterfalls, and native oak woodland. Glenveagh Castle, built in the 1870s, is a focal point. The park is known for its wild scenery and is home to a large herd of red deer and formerly to reintroduced golden eagles.

3. Wicklow Mountains National Park (Páirc Náisiúnta Sléibhte Chill MhantáinPáirc Náisiúnta Sléibhte Chill MhantáinIrish), County Wicklow: Stretching over 79 mile2 (205 km2), this is the largest of Ireland's national parks. It covers much of the Wicklow Mountains uplands, including blanket bog, heath, and areas of woodland. The historic monastic site of Glendalough is located within the park. It is a popular area for hiking and recreation due to its proximity to Dublin.

4. Connemara National Park (Páirc Náisiúnta ChonamaraPáirc Náisiúnta ChonamaraIrish), County Galway: Situated in the west of Ireland, this park covers nearly 12 mile2 (30 km2) of scenic mountains (including part of the Twelve Bens), expanses of bog, heath, grasslands, and woodlands. It offers insights into the unique landscape and cultural heritage of the Connemara region. Connemara ponies can often be seen grazing in the park.

5. The Burren National Park (Páirc Náisiúnta BhoirnePáirc Náisiúnta BhoirneIrish), County Clare: This park protects a portion of the unique karst landscape of The Burren, characterized by limestone pavement, glacial erratics, and a remarkable assemblage of Arctic, Alpine, and Mediterranean flora growing side-by-side. It is the smallest national park, covering approximately 5.8 mile2 (15 km2).

6. Ballycroy National Park (Páirc Náisiúnta Bhaile ChruaichPáirc Náisiúnta Bhaile ChruaichIrish), now part of the larger Wild Nephin National Park, County Mayo: Established in 1998, it covers 42 mile2 (110 km2) of the Owenduff/Nephin Complex, one of the last intact active blanket bog systems in Western Europe. It features a wilderness landscape of mountains, bogs, and the Owenduff River system, important for Atlantic salmon and Greenland white-fronted geese.

These national parks are vital for protecting Ireland's natural heritage and biodiversity, supporting scientific research, and promoting environmental awareness and sustainable tourism.

5. Politics

Ireland's political framework is a parliamentary democracy operating as a constitutional republic. The system is characterized by a separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, and it upholds principles of democratic accountability, human rights, and the rule of law. The country's political landscape is shaped by its history, its membership in the European Union, and evolving social values.

5.1. System of Government

Ireland is a constitutional republic and a parliamentary democracy. The Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireannBunreacht na hÉireannIrish), adopted in 1937 and subsequently amended, is the fundamental law of the state. It outlines the structure of government, the rights of citizens, and the powers and functions of state institutions. Key principles include popular sovereignty, the separation of powers, and a commitment to democratic and republican values. The Constitution can only be amended by a referendum of the people. The state operates a multi-party system.

5.2. President

The President of Ireland (Uachtarán na hÉireannUachtarán na hÉireannIrish) is the head of state. The President is directly elected by the people for a seven-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. The role is largely ceremonial, with the President representing the state at home and abroad. However, the President has certain important constitutional powers and functions, exercised in consultation with the Council of State, an advisory body. These powers include referring bills to the Supreme Court to test their constitutionality before signing them into law, convening and dissolving the Oireachtas (parliament) on the advice of the Taoiseach, and addressing the nation or the Oireachtas on matters of national importance. The official residence of the President is Áras an Uachtaráin in Phoenix Park, Dublin. Michael D. Higgins has served as President since November 2011.

5.3. Government (Executive)

The executive power of the state is exercised by or on the authority of the Government (Cabinet). The Government is headed by the Taoiseach (Prime Minister), who is the head of government. The Taoiseach is appointed by the President upon nomination by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of parliament) and is usually the leader of the political party or coalition that commands a majority in the Dáil. The Taoiseach nominates the other members of the Government (Ministers), who are then appointed by the President. The Government is constitutionally limited to fifteen members. The Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) is appointed by the Taoiseach from among the members of the Government and acts for the Taoiseach in their absence. The Government is collectively responsible to Dáil Éireann. If it ceases to retain the support of a majority in the Dáil, it must either resign or the Taoiseach must request the President to dissolve the Dáil and call a general election. Policy-making and implementation are key functions of the Government, operating through various government departments.

5.4. Legislature (Oireachtas)

The National Parliament of Ireland is the Oireachtas. It is a bicameral body consisting of the President of Ireland and two Houses: Dáil Éireann (House of Representatives) and Seanad Éireann (Senate). Leinster House in Dublin is the seat of the Oireachtas.

Dáil Éireann is the principal chamber and is directly elected by the people through a system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (PR-STV). As of recent configurations, it has 174 members, known as Teachtaí Dála (TDs), elected for a term not exceeding five years. The Dáil is responsible for making laws, forming governments, and holding the government accountable. All legislation must be passed by the Dáil.

Seanad Éireann is the upper house and has 60 members (Senators). Its composition is more complex: 11 Senators are nominated by the Taoiseach, 6 are elected by graduates of certain universities (National University of Ireland and University of Dublin), and 43 are elected from five vocational panels by an electorate comprising members of the incoming Dáil, the outgoing Seanad, and members of city and county councils. The Seanad's powers are limited compared to the Dáil; it can initiate or amend legislation (except for money bills, which it can only recommend changes to) but cannot veto bills passed by the Dáil indefinitely. It can delay bills for up to 90 days. The Seanad is often seen as a revising chamber and a forum for expertise.

The Oireachtas has the sole power to make laws for the state. Bills passed by both Houses (or deemed to have been passed by the Seanad) are presented to the President for signature to become law.

5.5. Judiciary

The judiciary in Ireland is independent in the exercise of its functions and subject only to the Constitution and the law. The Constitution of Ireland provides for a system of courts to administer justice. The main courts are the District Court, the Circuit Court, the High Court, the Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court.

- The District Court is the lowest court, dealing with minor civil and criminal matters.

- The Circuit Court has jurisdiction in more serious civil and criminal cases and can hear appeals from the District Court.

- The High Court has full original jurisdiction in all civil and criminal matters and can hear appeals from the Circuit Court. It also has the power of judicial review over the actions of lower courts and public bodies.

- The Court of Appeal, established in 2014, hears most appeals from the High Court in civil and criminal matters.

- The Supreme Court is the court of final appeal. It also has original jurisdiction in certain constitutional matters, such as determining the constitutionality of bills referred to it by the President or laws challenged after enactment.

Judges are appointed by the President on the advice of the Government. The legal system is based on common law, as modified by statute law and the Constitution. Judicial review allows the courts to ensure that laws and actions of the state are compatible with the Constitution. Trials for serious offences are typically held before a jury.

5.6. Political Parties and Elections

Ireland has a multi-party system, with several political parties represented in the Oireachtas. Historically, Irish politics was dominated by two major parties:

- Fianna Fáil: Traditionally a populist and nationalist party, generally center-right on economic issues but with a broad appeal.

- Fine Gael: Generally center-right, with more economically liberal and pro-European stances.

Both parties originated from the opposing sides of the Irish Civil War. In recent decades, the political landscape has become more fragmented. Other significant parties include:

- Sinn Féin: A left-wing republican party, advocating for a united Ireland and socialist policies. It has seen a significant rise in support in recent years.

- Labour Party: A social democratic party, traditionally aligned with the trade union movement.

- Green Party: Focuses on environmental issues and social justice.

- Social Democrats: A centre-left party emphasizing social justice and public services.

- People Before Profit/Solidarity: An electoral alliance of far-left and socialist parties.

- Aontú: A republican and socially conservative party.

Independent politicians also play a significant role in Irish politics, often holding a considerable number of seats in the Dáil.

General elections for Dáil Éireann must be held at least every five years. The electoral system is proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (PR-STV). This system is designed to ensure that the distribution of seats in the Dáil reflects the proportion of votes cast for different parties and candidates, and it often leads to coalition governments, as it is rare for a single party to win an overall majority. Referendums are required for constitutional amendments and are sometimes held on other major policy issues.

5.7. Local Government

Local government in Ireland is administered through a system of local authorities. The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 was the foundational statute, and the Twentieth Amendment in 1999 provided constitutional recognition for local government. The Local Government Reform Act 2014 significantly restructured the system.

Currently, there are 31 local authorities:

- 26 County Councils

- 2 City and County Councils (Limerick, Waterford)

- 3 City Councils (Dublin, Cork, Galway)

The traditional 26 counties of Ireland form the basis for these areas, though some have been modified for administrative purposes (e.g., County Dublin is divided into four local authority areas: Dublin City, Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown, Fingal, and South Dublin; County Tipperary is now a single administrative county).

Local authorities are responsible for a range of services, including:

- Housing and building

- Road transportation and safety (local roads)

- Water supply and sewerage (though Irish Water, a national utility, now has primary responsibility for water services)

- Development incentives and controls (planning)

- Environmental protection

- Recreation and amenity (libraries, parks, etc.)

- Fire services

Councillors are elected to local authorities for five-year terms using the PR-STV system. Counties (with the exception of the three counties in Dublin that are entirely urban or peri-urban) are divided into municipal districts, which have some specific powers and responsibilities within the broader county council structure. A previous tier of town councils was abolished in 2014. Local authorities are funded through a combination of central government grants, local property tax, and charges for certain services. Three Regional Assemblies exist for planning, coordination, and statistical purposes but have no direct administrative role.

| # | Council Area | # | Council Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fingal | 17 | Kilkenny |

| 2 | Dublin City | 18 | Waterford City and County |

| 3 | Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown | 19 | Cork City |

| 4 | South Dublin | 20 | Cork County |

| 5 | Wicklow | 21 | Kerry |

| 6 | Wexford | 22 | Limerick City and County |

| 7 | Carlow | 23 | Tipperary |

| 8 | Kildare | 24 | Clare |

| 9 | Meath | 25 | Galway County |

| 10 | Louth | 26 | Galway City |

| 11 | Monaghan | 27 | Mayo |

| 12 | Cavan | 28 | Roscommon |

| 13 | Longford | 29 | Sligo |

| 14 | Westmeath | 30 | Leitrim |

| 15 | Offaly | 31 | Donegal |

| 16 | Laois |

5.8. Military (Defence Forces)

The Irish Defence Forces (Óglaigh na hÉireannÓglaigh na hÉireannIrish) are the military of Ireland. They encompass the Army, Air Corps, Naval Service, and Reserve Defence Force (Army Reserve and Naval Service Reserve). The President of Ireland is the formal Supreme Commander, but in practice, the Defence Forces answer to the Government via the Minister for Defence.

Ireland has a longstanding policy of military neutrality, meaning it is not a member of NATO. This neutrality is characterized by non-alignment in military conflicts. However, Ireland participates in the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC). It also participates in the EU's Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in certain aspects.

The roles of the Defence Forces include:

- Defence of the state against armed aggression.

- Aid to the civil power (assisting An Garda Síochána, the national police service, in situations such as maintaining public order, bomb disposal, or national emergencies).

- Participation in international peace support, crisis management, and humanitarian relief operations under UN mandate, or as part of EU or PfP missions. Ireland has a long and respected tradition of contributing to UN peacekeeping missions since 1960, serving in numerous conflict zones around the world.

- Fishery protection (by the Naval Service).

- Other duties such as search and rescue (primarily by the Air Corps and Naval Service) and ministerial air transport.

The Defence Forces are relatively small, with an establishment of just under 10,000 full-time personnel. Deployments of Irish troops in conflict zones are governed by a "triple-lock" system, requiring approval from the UN, the Government, and Dáil Éireann. In 2017, Ireland signed the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

6. Foreign Relations

Ireland's foreign policy is shaped by its history, its commitment to international law and multilateralism, its membership in the European Union, and its policy of military neutrality. Key aspects include its relationships with the United Kingdom and the United States, its active role in the UN, particularly in peacekeeping, and its engagement within the EU.

6.1. Foreign Policy and Neutrality

Ireland has a traditional policy of military neutrality, meaning it does not participate in military alliances such as NATO. This policy originated prior to World War II, during which Ireland remained neutral (a period known as The Emergency). Post-war, neutrality has continued, though its interpretation has evolved. Ireland participates in the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) program and certain aspects of the EU's Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), focusing on peacekeeping, crisis management, and humanitarian tasks. The "triple-lock" mechanism (UN mandate, Government approval, and Dáil Éireann approval) governs the deployment of Irish troops to overseas missions.

Key foreign policy objectives include:

- Promoting international peace and security, disarmament, and human rights.

- Supporting the United Nations and a rules-based international order.

- Active and constructive membership in the European Union.

- Fostering strong bilateral relations, particularly with the United Kingdom and the United States.

- Supporting Irish citizens abroad and promoting Irish culture and economic interests internationally.

- Contributing to international development and humanitarian aid, with Irish Aid being the government's official development assistance program.

During the Cold War, while officially neutral, Ireland's sympathies generally lay with the Western democracies. There were instances of quiet cooperation, such as authorizing the search of Cuban and Czechoslovak aircraft at Shannon Airport during the Cuban Missile Crisis and passing information to the CIA. Shannon Airport has also been used by the U.S. military for logistical purposes, which has sometimes been a point of domestic political debate in the context of Irish neutrality.

6.2. Relations with the United Kingdom

The relationship between Ireland and the United Kingdom is complex, deeply intertwined by geography, shared history (including centuries of British rule and Irish independence struggles), close economic ties, and significant people-to-people links.

Historically, the relationship was defined by British colonization and Irish resistance, culminating in the Irish War of Independence and the partition of Ireland in 1921, which created the Irish Free State (later the Republic of Ireland) and Northern Ireland (which remained part of the UK). The Troubles in Northern Ireland (late 1960s-1998) placed considerable strain on Anglo-Irish relations, as both governments worked to find a political solution.

The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 was a landmark achievement, co-brokered by the Irish and British governments. It established power-sharing in Northern Ireland and cross-border institutions, significantly improving relations. The Common Travel Area allows for free movement of people between the two countries.

Economic links are substantial, with significant trade and investment. However, the UK's withdrawal from the European Union (Brexit) has introduced new complexities, particularly concerning the border on the island of Ireland, trade arrangements (the Northern Ireland Protocol), and the overall bilateral relationship. Both governments continue to work closely on issues related to Northern Ireland and shared interests. Cultural ties, including language, sports, and media, remain strong.

6.3. Relations with the United States

Relations between Ireland and the United States are strong, founded on deep historical, cultural, and economic ties. A significant factor is the large Irish diaspora in the U.S., with millions of Americans claiming Irish ancestry. This diaspora has historically played a role in Irish political and economic life, including support for Irish independence and investment in the Irish economy.

Politically, the U.S. played a supportive role in the Northern Ireland peace process, notably during the Clinton administration. There is regular high-level diplomatic engagement, and the annual Saint Patrick's Day celebrations in the U.S., particularly at the White House, symbolize the close relationship.

Economically, the U.S. is a major trading partner and the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Ireland. Many U.S. multinational corporations, especially in the technology, pharmaceutical, and financial services sectors, have their European headquarters in Ireland, attracted by its low corporation tax rate, educated workforce, and EU membership. This investment has been a key driver of Irish economic growth. Culturally, Irish music, literature, and traditions are popular in the U.S., and American culture is widely consumed in Ireland. Tourism flows in both directions are significant.

6.4. European Union Membership

Ireland joined the European Communities (EC), the precursor to the European Union (EU), on January 1, 1973, along with the United Kingdom and Denmark. Membership in the EU has had a transformative impact on Ireland's economy, society, and foreign policy.

Economically, EU membership provided access to the European single market, attracted significant foreign direct investment, and provided substantial funding through the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and structural funds, which helped modernize Ireland's infrastructure and economy. Ireland adopted the Euro as its currency on January 1, 1999 (cash introduced in 2002).

Politically, EU membership has enhanced Ireland's international standing and provided a platform to pursue its foreign policy objectives within a multilateral framework. Ireland has generally been a pro-European member state, actively participating in EU decision-making. It has held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union on multiple occasions. EU laws and directives have influenced many areas of Irish life, from environmental protection and consumer rights to employment law.

Socially, EU membership has contributed to greater openness, increased travel and educational exchange opportunities (e.g., through the Erasmus Programme), and alignment with European social norms. The free movement of people within the EU has led to increased immigration into Ireland and emigration of Irish citizens to other EU countries. Brexit has posed new challenges for Ireland, particularly concerning its border with Northern Ireland and its trade relationship with the UK, further emphasizing the importance of its EU membership.

6.5. United Nations and Peacekeeping

Ireland became a member of the United Nations (UN) on December 14, 1955. Since joining, Ireland has been an active and committed participant in the organization, strongly supporting multilateralism, international law, human rights, disarmament, and sustainable development.

A hallmark of Ireland's UN membership is its significant and continuous contribution to UN peacekeeping operations. The Irish Defence Forces have served in numerous UN missions across the globe since 1960, starting with the Congo Crisis (ONUC). Irish peacekeepers have earned a strong international reputation for their professionalism and dedication, serving in regions such as Cyprus (UNFICYP), Lebanon (UNIFIL), the Middle East (UNTSO, UNDOF), Bosnia and Herzegovina (SFOR/EUFOR), Kosovo (KFOR), Liberia (UNMIL), and Mali (MINUSMA), among others. This commitment to peacekeeping is a core element of Irish foreign policy and is closely linked to its policy of military neutrality.

Ireland has also played an active role in UN diplomacy, championing causes such as nuclear disarmament (instrumental in the development of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty), decolonization, and development aid. It has served multiple terms on the UN Security Council as a non-permanent member, using its position to advocate for peace, security, and human rights. Irish Aid, the government's official development assistance program, works to combat poverty and hunger, often in partnership with UN agencies.

7. Economy

The Irish economy has undergone a significant transformation from a largely agrarian base to a modern, open, and globalized economy. It is characterized by a strong reliance on international trade and foreign direct investment, particularly in high-tech sectors. While experiencing periods of rapid growth, it has also faced challenges such as economic inequality, the impact of global financial crises, and debates surrounding its taxation policies. Social aspects like labor rights, environmental sustainability, and social equity are increasingly considered in the context of economic development.

7.1. Economic Development and Trends

Historically, Ireland was one of the less developed economies in Western Europe, heavily dependent on agriculture. After joining the European Communities (now EU) in 1973, the economy began to modernize, aided by EU subsidies and access to wider markets.

The period from the mid-1990s to 2007 is known as the Celtic Tiger, characterized by exceptionally high rates of economic growth. This boom was driven by factors including low corporation tax, foreign direct investment (FDI) from multinational corporations (especially US tech and pharmaceutical companies), an educated English-speaking workforce, EU membership, social partnership agreements between government, employers, and unions, and investment in infrastructure and education. This era led to increased employment, rising living standards, and significant immigration.

However, the Celtic Tiger ended abruptly with the global financial crisis of 2008. Ireland was particularly hard-hit due to a domestic property bubble burst and a subsequent banking crisis. The government had to bail out several major banks, leading to a sovereign debt crisis. Ireland received a bailout package from the EU and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2010 and implemented austerity measures. The period saw a sharp rise in unemployment and renewed emigration.

Ireland officially exited the bailout program in December 2013. The economy subsequently entered a period of strong recovery and growth from around 2014, again driven by exports from the multinational sector. However, issues of economic inequality, housing shortages, and pressure on public services have persisted. The reliance on FDI and the impact of multinational accounting practices (such as profit shifting) have led to debates about the true health and sustainability of the domestic economy, prompting the Central Statistics Office to develop alternative measures like Modified Gross National Income (GNI*) to provide a more accurate picture. Future outlook is influenced by global economic trends, EU policies, and the impact of international tax reforms. Sustainable development and addressing climate change are also increasingly important economic considerations.

7.2. Major Industries

The Irish economy is diverse, with several key sectors contributing to its GDP and employment. These include:

- Information Technology (ICT): Ireland is a major European hub for global technology companies. Many leading firms such as Google, Apple, Microsoft, Meta (Facebook), and Intel have their European headquarters or significant operations in Ireland. The sector spans software development, hardware manufacturing, data centers, and IT services.

- Pharmaceuticals and Medical Technology: Ireland is one of the world's largest exporters of pharmaceuticals. Numerous major multinational pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical companies have manufacturing and research facilities in the country. The medical technology (medtech) sector is also a significant employer and exporter.

- Financial Services: The International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) in Dublin is a hub for international financial services, including banking, fund administration, insurance, and aircraft leasing.

- Agriculture and Food Production: While its share of GDP has declined, agriculture remains an important sector, particularly in rural areas. Key products include beef, dairy (milk, butter, cheese), lamb, and cereals. The food and beverage industry, building on agricultural output, is a major employer and exporter (e.g., Guinness, Irish whiskey, dairy products).

- Tourism: Tourism is a significant contributor to the Irish economy, attracting visitors with its scenery, heritage, culture, and hospitality. It supports a large number of jobs across the country.

- Manufacturing: Beyond pharmaceuticals and medtech, other manufacturing sub-sectors include engineering, electronics, and food processing.

- Retail and Wholesale Trade: A major source of domestic employment.

- Construction: Subject to cyclical trends, the construction sector plays a role in infrastructure development and housing.

The economy benefits from a skilled workforce, a pro-business environment, and its membership in the European Union.

7.3. Trade

Ireland has a highly open economy, with international trade playing a crucial role. It consistently runs a significant trade surplus.

- Main Exports:

- Pharmaceuticals and organic chemicals are the largest export categories, driven by multinational corporations.

- Medical devices and equipment.

- Software and ICT services.

- Aircraft and parts (Ireland is a global hub for aircraft leasing).

- Food and beverages, including beef, dairy products (butter, cheese, infant formula), and alcoholic drinks (Irish whiskey, beer).

- Machinery and transport equipment.

- Main Imports:

- Machinery and transport equipment (including cars and industrial machinery).

- Chemicals and related products (often inputs for the pharmaceutical industry).

- Petroleum and petroleum products.

- Manufactured goods.

- Foodstuffs not produced domestically in sufficient quantities.

- Computer hardware and components.

- Primary Trading Partners:

- The European Union is collectively Ireland's largest trading partner. Key EU partners include Germany, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

- The United States is a vital trading partner, both as an export market (especially for pharmaceuticals and ICT) and a source of imports.

- The United Kingdom remains a very important trading partner, despite Brexit. Historically, it was Ireland's single largest partner. The trading relationship is now governed by the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement and the Northern Ireland Protocol.

- Other significant partners include Switzerland and China.

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) publishes detailed trade statistics. The balance of trade is significantly influenced by the activities of multinational corporations operating in Ireland, particularly regarding the movement of intellectual property and high-value goods.

7.4. Taxation Policy

Ireland's taxation policy, particularly its corporation tax regime, has been a central pillar of its economic strategy to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) and stimulate economic growth.

The headline rate of corporation tax on trading profits has been 12.5% since 2003, which is one of the lowest in the OECD and the European Union. This low rate has been highly successful in attracting multinational corporations (MNCs), especially from the United States, in sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals, and financial services. These MNCs have contributed significantly to employment, exports, and overall economic activity in Ireland.

In addition to the low headline rate, Ireland has historically offered other tax incentives and features, such as research and development (R&D) tax credits and a regime for intellectual property (IP), which have further enhanced its attractiveness for FDI.

However, Ireland's corporation tax policy has also faced international scrutiny and controversy. Critics, including some other EU member states and international organizations, have labelled Ireland a "corporate tax haven" or a "low-tax jurisdiction," arguing that its policies facilitate aggressive tax planning and profit shifting by MNCs, thereby eroding the tax bases of other countries. High-profile cases, such as the EU Commission's state aid ruling against Apple and Ireland (which Ireland successfully appealed), have highlighted these tensions.

In response to international pressure and changes in global tax standards (such as the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project), Ireland has made changes to its tax code, phasing out controversial schemes like the "Double Irish". Ireland has also agreed to and is implementing the OECD's two-pillar solution to address the tax challenges arising from digitalization, including a global minimum effective corporation tax rate of 15% for large MNCs, which came into effect in Ireland in 2024.

The social impact of the taxation policy includes debates about the distribution of the benefits of FDI, the sustainability of an economic model heavily reliant on MNCs, and the fairness of the overall tax system, including personal income tax and other levies.

7.5. Energy

Ireland's energy sector is undergoing a significant transition, driven by the need to meet climate change targets, enhance energy security, and reduce reliance on imported fossil fuels.

- Energy Sources: Historically, Ireland has been heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels, particularly oil and natural gas, for electricity generation, heating, and transport. Peat, traditionally harvested from Irish bogs, has also been a domestic source for power generation, though its use is declining due to environmental concerns. Natural gas is sourced from domestic fields like the Corrib gas field and via interconnectors with the UK.

- Electricity Generation: The electricity grid is managed by EirGrid. Generation comes from a mix of natural gas, coal (phasing out), peat (phasing out), and increasingly, renewable sources.

- Renewable Energy: Ireland has significant renewable energy potential, particularly from wind. The country has set ambitious targets for renewable electricity, aiming for 80% by 2030. Wind energy, both onshore and increasingly offshore, is the primary renewable source. Solar power, bioenergy, and hydropower also contribute. Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) plays a key role in promoting renewable energy and energy efficiency.

- Energy Consumption: Transport and heating are major components of energy consumption. Efforts are underway to promote electric vehicles and improve energy efficiency in buildings to reduce reliance on fossil fuels in these sectors.

- Energy Policy and Climate Change: Ireland's energy policy is strongly influenced by EU targets for emissions reduction and renewable energy. The Climate Action Plan outlines measures to achieve a climate-neutral economy by 2050. This includes significant investment in renewable energy infrastructure, grid modernization, energy efficiency programs, and research into new technologies like green hydrogen.

- Energy Security: Given its island location and historical reliance on imports, energy security is a key concern. Diversifying energy sources, increasing domestic renewable generation, and maintaining robust interconnections with neighboring grids (like the UK and potentially France via the Celtic Interconnector) are important strategies.

- Environmental Considerations: The shift away from fossil fuels and peat is driven by the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and protect biodiversity. The environmental impact of energy projects, including renewable energy developments, is also a consideration in planning and policy.

7.6. Transport

Ireland's transport infrastructure includes road, rail, air, and sea networks, which have seen significant development and investment, particularly since the 1990s.

- Road Network: Roads are the dominant mode of transport for both passengers and freight. The network comprises motorways, national primary roads, national secondary roads, regional roads, and local roads. A significant motorway network now connects Dublin with other major cities like Cork, Limerick, Galway, and Waterford, as well as key routes towards Northern Ireland. Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) is responsible for national roads and motorways. Bus services, provided by the state-owned Bus Éireann (national and regional) and Dublin Bus (Dublin area), as well as private operators, are extensive.

- Rail Network: The rail network is operated by the state-owned Iarnród Éireann (Irish Rail). It provides intercity services connecting major towns and cities, commuter services in the Dublin and Cork areas, and limited freight services. The network primarily radiates from Dublin. The Enterprise service, jointly operated with NI Railways, connects Dublin and Belfast. The Dublin Area Rapid Transit (DART) is an electrified suburban rail line serving the Dublin coast.

- Air Transport: Ireland has three main international airports: Dublin Airport, Cork Airport, and Shannon Airport. Dublin Airport is by far the busiest, serving as a hub for flag carrier Aer Lingus and low-cost giant Ryanair. Several regional airports also operate. Ireland's island location and strong international connections (particularly with the UK, Europe, and North America) make air travel crucial.

- Sea Ports: Major ports include Dublin Port, Cork, Rosslare Europort, Shannon Foynes Port, and Waterford Port. These handle significant freight traffic and some passenger ferry services, connecting Ireland with the UK and continental Europe.

- Public Transport in Cities: Dublin has the most extensive public transport system, including Dublin Bus, DART, Luas (a light rail/tram system), and commuter rail. Other cities like Cork, Limerick, and Galway also have urban bus services. Cycling infrastructure is being developed in urban areas.

Challenges in the transport sector include road congestion in urban areas, the need for further investment in public transport and sustainable mobility, and reducing carbon emissions from the transport sector to meet climate targets.

8. Society

Irish society has undergone profound transformations in recent decades, moving from a relatively homogenous and conservative country to a more diverse, secular, and socially liberal one. Key aspects include its demographic trends, evolving cultural makeup, and ongoing debates about social welfare, human rights, and the role of traditional institutions.

8.1. Demographics

According to the 2022 census, the population of Ireland was 5,149,139, an 8% increase since the 2016 census. This represents a significant recovery from historical population decline caused by famine and emigration in the 19th and much of the 20th centuries.

Key demographic characteristics include:

- Population Growth: Ireland has experienced periods of rapid population growth, notably during the "Celtic Tiger" era (mid-1990s to 2007), driven by both natural increase and significant net immigration. After a period of net emigration following the 2008 financial crisis, net immigration has resumed.

- Birth and Fertility Rates: Ireland historically had one of the highest birth rates in Europe. While the total fertility rate (TFR) has declined, it remained relatively high compared to other EU countries for some time. In 2017, the TFR was estimated at 1.80 children per woman, below the replacement rate of 2.1. The proportion of births outside marriage has increased significantly.

- Age Structure: Ireland has a relatively young population compared to many other European countries, though it is aging. The median age in 2018 was 37.1 years.

- Urbanization: There is a continued trend towards urbanization, with a large proportion of the population living in and around Dublin. Other significant urban centers include Cork, Limerick, Galway, and Waterford.

- Life Expectancy: Life expectancy in Ireland is high and has been increasing. In 2021, it was approximately 82.4 years (80.5 for men, 84.3 for women).

- Migration: Ireland has a long history of emigration. However, economic prosperity has also made it a destination for immigrants, contributing to a more diverse population.

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) is the primary source for demographic data.

8.1.1. Ethnicity and Immigration

Irish society has become increasingly multicultural, particularly since the economic boom of the 1990s. Historically, the population was predominantly of Irish ethnic origin.

- Ethnic Composition: According to the 2016 census, 82.2% of the population identified as White Irish. Other significant ethnic groups included Other White (9.5%), Asian or Asian Irish (2.1%), Black or Black Irish (1.2%), and those of mixed or other backgrounds. The "Irish Traveller" community (0.7%) is a distinct indigenous ethnic minority group with its own unique heritage and culture, officially recognized by the Irish state in 2017.

- Immigration: Ireland experienced significant net immigration during the Celtic Tiger years, attracting workers from other EU countries (especially Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia after the 2004 EU enlargement) and from outside the EU. While the 2008 financial crisis led to a period of net emigration, net immigration has since resumed. The 2022 census recorded 631,785 non-Irish nationals, with the largest groups being Polish, UK nationals, Indian, Romanian, and Lithuanian.

- Integration and Rights of Minorities: The integration of immigrants and the rights of ethnic minorities are important social and political issues. Ireland has legislation prohibiting discrimination on grounds of race or ethnicity. Government policies and civil society organizations work towards promoting integration, interculturalism, and combating racism. Challenges include access to services, employment, housing, and addressing discrimination. The rights and welfare of asylum seekers and refugees are also a significant concern, with ongoing debates about the direct provision system. Promoting a welcoming and inclusive society for all ethnic groups is a stated goal, aligning with social liberal values of equality and human rights.

8.2. Languages

Ireland has two official languages: Irish (GaeilgeGaeilgeIrish) and English.

- Irish (Gaeilge): The Constitution of Ireland designates Irish as "the national language" and the "first official language." It is a Celtic language and was the vernacular of the majority of the population until the 19th century. Its usage declined significantly due to factors such as English colonization, the Great Famine, and emigration.

Today, Irish is spoken as a community language primarily in Gaeltacht regions, which are mainly located along the western and southern coasts. According to the 2016 census, about 1.75 million people (around 40% of the population) reported being able to speak Irish, but of these, fewer than 74,000 spoke it on a daily basis outside the education system.

There are ongoing language policies and revitalization efforts to promote Irish, supported by the state. These include the teaching of Irish as a compulsory subject in schools, public service broadcasting in Irish (TG4 television channel, RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta radio station), and official status within the European Union. Road signs and official documents are often bilingual.

- English: English is designated as the "second official language" but is the dominant language used in everyday life, business, government, and media. Hiberno-English refers to the varieties of English spoken in Ireland, which have distinct phonetic, grammatical, and lexical features.

- Other Languages: Due to immigration, a variety of other languages are spoken in Ireland. Polish is the most widely spoken language after English and Irish. Other languages with significant numbers of speakers include Lithuanian, Romanian, French, German, and Spanish. Shelta is a language spoken by the Irish Traveller community.

Language policy aims to support bilingualism and the rights of citizens to use Irish in official dealings, though practical implementation can be challenging. The revitalization of the Irish language is viewed as an important aspect of cultural heritage and identity.

8.3. Religion

Religion has historically played a significant role in Irish society, though its influence has markedly declined in recent decades, accompanied by increasing secularization and religious diversity. Religious freedom is constitutionally guaranteed.

- Roman Catholicism: Ireland has traditionally been a predominantly Roman Catholic country. According to the 2022 census, 69.1% of the population identified as Roman Catholic. This represents a continued sharp decline from 78.3% in 2016 and 84.2% in 2011. The Catholic Church historically wielded considerable influence over social policy, education, and healthcare. However, a series of scandals involving clerical abuse, coupled with broader societal changes, has led to a significant decrease in religious practice and the Church's public authority.

- No Religion: The proportion of the population identifying as having "No Religion" has increased substantially, reaching 14.5% in the 2022 census, up from 9.8% in 2016. This group is now the second largest after Roman Catholics, reflecting a growing trend towards secularism, particularly among younger generations.

- Church of Ireland: The Church of Ireland (part of the Anglican Communion) is the largest Protestant denomination, with 2.5% of the population identifying as such in 2022. Its membership declined for much of the 20th century but has seen some stabilization or slight increase in recent years.

- Other Christian Denominations: Other Protestant denominations include Presbyterians (0.5% in 2022) and Methodists. Orthodox Christianity has grown, largely due to immigration from Eastern Europe, accounting for 2.0% of the population in 2022.

- Islam: The Muslim population has also grown through immigration, representing 1.6% of the population in 2022.

- Other Religions: Smaller communities of Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, and other faiths also exist in Ireland, contributing to the country's increasing religious diversity (collectively 3.1% in 2022). 6.7% of the population did not state their religion in the 2022 census.

The changing religious landscape reflects broader social liberalization in Ireland, with a move away from traditional religious authority and towards greater individual autonomy in matters of faith and belief. The state has become more secular, with constitutional changes (like the removal of the "special position" of the Catholic Church in 1972) and legal reforms in areas previously influenced by religious doctrine.

8.4. Education

Ireland's education system comprises primary, secondary, and higher education, largely directed by the Department of Education. Education is compulsory from age 6 to 16, or until students have completed three years of secondary education.

- Primary Education: Typically starts at age 4 or 5 and lasts for eight years. Most primary schools are state-funded but may be under denominational (often Catholic) patronage, though there is a growing movement for more multi-denominational and non-denominational schools. The curriculum is standardized.

- Secondary Education: Consists of a three-year junior cycle, culminating in the Junior Certificate examination, followed by a two- or three-year senior cycle. Students in the senior cycle can opt for the Transition Year (an optional year focused on personal development and work experience) before a two-year program leading to the Leaving Certificate examination. The Leaving Certificate is the main university entrance examination.

- Higher Education: Ireland has a well-regarded higher education sector, including universities, institutes of technology (now often technological universities), and colleges of education. Major universities include Trinity College Dublin, University College Dublin, University College Cork, University of Galway, and Maynooth University. Access to higher education is competitive, based on Leaving Certificate results. For EU citizens, undergraduate tuition fees are largely covered by the state, though students pay a "student contribution charge."

- Further Education and Training (FET): This sector provides vocational and skills-based training, apprenticeships, and adult education, managed by SOLAS and local Education and Training Boards (ETBs).

Educational attainment in Ireland is high, with a large proportion of the population holding third-level qualifications. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has generally ranked Irish students above the OECD average in reading, mathematics, and science. Educational policy focuses on quality, access, inclusion, and adapting to the needs of a modern economy. Challenges include addressing educational disadvantage, managing school patronage diversity, and ensuring adequate funding and resources.

8.5. Healthcare

Healthcare in Ireland is delivered through a mixed public and private system. The Department of Health sets overall policy, and the Health Service Executive (HSE) is responsible for providing public health and social care services.

- Public Healthcare System: All residents of Ireland are entitled to access public healthcare services. Eligibility for services free of charge or at a subsidised rate depends on factors like income, age, and medical condition.

- A Medical card system provides free access to a range of services (including GP visits, prescribed medications, hospital care) for those below certain income thresholds, and for all children under 8 as of 2023 (expanding).

- Those without a medical card may still be eligible for certain subsidised services or specific schemes (e.g., GP visit cards for certain age groups or income levels, maternity and infant care schemes, Long-Term Illness Scheme).

- Public hospital care may involve charges for inpatient stays and emergency department visits for those without a medical card, though these are often capped.

- Private Healthcare System: A significant portion of the population (around 45-50%) holds private health insurance, which provides access to private hospitals and faster access to consultants and certain procedures in both public and private facilities. Major private health insurers include Vhi Healthcare, Laya Healthcare, and Irish Life Health.