1. Biography

Josemaría Escrivá's personal history, from his early life to his later activities, details his path from a financially struggling family to the founder of a globally influential Catholic organization.

1.1. Early Life

José María Mariano Escrivá y Albás was born on 9 January 1902, in the small town of Barbastro, Huesca, Spain. He was the second of six children and the first of two sons born to José Escrivá y Corzán, a merchant, and María de los Dolores Albás y Blanc. In 1915, his family was forced to relocate to Logroño, La Rioja, after his father's textile company went bankrupt, leading José Escrivá to work as a clerk in a clothing store. It was during his youth, reportedly after observing footprints left in the snow by a barefoot monk, that Josemaría first felt a calling, believing he had "been chosen for something."

1.2. Education and Early Priesthood

With his father's encouragement, Escrivá decided to become a priest of the Catholic Church. He pursued his studies in Logroño and then in Zaragoza. He was ordained as a deacon on 20 December 1924, and as a priest in Zaragoza on 28 March 1925. After a brief assignment in the rural parish of Perdiguera, he moved to Madrid in 1927 to continue his education in law at the Central University. In Madrid, he supported himself as a private tutor and served as a chaplain for the Foundation of Santa Isabel, which included the royal Convent of Santa Isabel and a school managed by the Little Sisters of the Assumption. During this time, he also engaged in pastoral work among the poor, the sick, and the dying in the city's slums and hospitals.

2. Founding of Opus Dei

The establishment of Opus Dei was rooted in a profound spiritual inspiration that guided Escrivá to create an organization dedicated to helping laypeople and priests pursue holiness in their everyday lives, even amidst political turmoil, eventually gaining papal approval and expanding globally.

2.1. Foundational Vision and Early Work

On 2 October 1928, after a period of intense prayer and contemplation, Josemaría Escrivá "saw" what he believed to be God's will for him: the establishment of Opus Dei, which means "Work of God" in Latin. This vision was to create a path for Catholics to achieve personal holiness and engage in apostolate through their ordinary secular work, without changing their social status or daily routines. From its inception, Escrivá dedicated himself entirely to this mission, initiating a wide-ranging apostolate that particularly focused on serving the poor and the sick in Madrid's marginalized communities and hospitals.

2.2. Activities During the Spanish Civil War

During the tumultuous Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Escrivá continued his pastoral activities in Madrid despite the intense anti-clerical persecution from the Republican side. He worked covertly until he was forced to flee Madrid. He traversed the Pyrenees through Andorra and France, eventually reaching Burgos, which served as the headquarters for General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces. After the war concluded in 1939 with Franco's victory, Escrivá returned to Madrid to resume his studies. He completed his doctorate in law with a thesis on the historical jurisdiction of the Abbess of Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas.

2.3. Papal Approval and Global Expansion

On 14 February 1943, Escrivá founded the Priestly Society of the Holy Cross, an entity closely associated with Opus Dei, which allowed members to receive priestly ordination and enabled diocesan priests to pursue holiness according to Opus Dei's spirituality while remaining fully subject to their own bishops. In 1946, Escrivá relocated to Rome, which became the new center for Opus Dei's burgeoning global activities.

Opus Dei received its initial pontifical approval in 1947 and final approval as an institution of pontifical right on 16 June 1950. With this recognition, Escrivá tirelessly guided the worldwide development of Opus Dei, inspiring a vast mobilization of lay people to pursue holiness in their daily lives. He actively promoted numerous initiatives focused on evangelization and human welfare, fostering vocations to the priesthood and religious life across the globe. His primary focus remained the spiritual formation of Opus Dei members, driving the organization's widespread international development.

3. Later Life and Global Expansion

In his later years, Josemaría Escrivá oversaw the significant expansion of Opus Dei, taking on various ecclesiastical and academic roles, and establishing educational and spiritual initiatives that solidified his legacy.

3.1. Global Development of Opus Dei

By the time of Escrivá's death in 1975, Opus Dei had expanded significantly, boasting approximately 60,000 members across 80 countries. This substantial growth reflected the successful dissemination of his message on the universal call to holiness and the sanctification of ordinary life. During the 1960s and 1970s, Escrivá himself promoted and supervised the design and construction of a major shrine at Torreciudad in Aragon, Spain. This shrine, which opened on 7 July 1975, shortly after his death, continues to serve as the spiritual heart of Opus Dei and an important destination for Catholic pilgrimage.

3.2. Ecclesiastical Offices and Academic Contributions

Josemaría Escrivá held several significant ecclesiastical and academic positions. In 1950, Pope Pius XII appointed him an Honorary Domestic Prelate, allowing him to use the title of Monsignor. He furthered his theological studies, earning a doctorate in theology from the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome in 1955. Escrivá served as a consultor to two important Vatican congregations: the Congregation for Seminaries and Universities and the Pontifical Commission for the Authentic Interpretation of the Code of Canon Law. He was also an honorary member of the Pontifical Academy of Theology. The teachings of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), which emphasized the universal call to holiness, the vital role of the laity, and the Mass as the cornerstone of Christian life, resonated strongly with Escrivá's own foundational message.

3.3. Educational and Spiritual Initiatives

Escrivá was instrumental in establishing several significant educational institutions. In 1948, he founded the Collegium Romanum Sanctae Crucis (Roman College of the Holy Cross) in Rome, which served as Opus Dei's primary educational center for men. Five years later, in 1953, he established the Collegium Romanum Sanctae Mariae (Roman College of Saint Mary) for the women's section of Opus Dei. These institutions have since been integrated into the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross. Beyond Rome, Escrivá also founded secular universities affiliated with Opus Dei, notably the University of Navarre in Pamplona, Spain, and the University of Piura in Peru. In addition to academic endeavors, he passionately promoted spiritual sites, such as the shrine at Torreciudad, which became a significant pilgrimage destination and a spiritual center for Opus Dei members worldwide.

4. Spirituality and Teachings

Josemaría Escrivá's core spiritual philosophy revolved around the belief that holiness is accessible to everyone through their ordinary daily lives and work, supported by a profound personal devotional practice that included prayer, Marian devotion, and corporal mortification.

4.1. Universal Call to Holiness and Sanctification of Ordinary Life

Escrivá's central teaching was the universal call to holiness, proclaiming that all individuals, regardless of their state in life, are called to become saints. He vehemently emphasized the "sanctification of ordinary life," asserting that everyday work and mundane activities could be transformed into a path to God. This principle, which he had preached since founding Opus Dei in 1928, found significant resonance and later confirmation in the fundamental nucleus of the Church's magisterium articulated by the Second Vatican Council. Pope John Paul II described Escrivá as a "master in the practice of prayer" and the "saint of ordinary life," highlighting his conviction that daily life and work are integral to holiness, a message destined to be an "inexhaustible source of spiritual light."

4.2. Personal Practices and Devotion

Escrivá's personal spiritual disciplines included a deep commitment to prayer, which he considered an extraordinary "weapon" for redeeming the world. His life story could be traced through five brief aspirations: Domine, ut videam!Lord, that I might see!Latin, expressing his desire to discern God's will; Domina, ut sit!Lady, that it might be!Latin, signifying his readiness to fulfill it; Omnes cum Petro ad Iesum per Mariam!All together with Peter to Jesus through Mary!Latin, showing his zeal for souls, fidelity to the Church, and ardent devotion to Mary; Regnare Christum volumus!We want Christ to reign!Latin, reflecting his pastoral concern to spread the call to divine sonship; and Deo omnis gloria!All the glory to God!Latin, dedicating all to God. Pope John Paul II noted that love for the Virgin Mary was a constant in Escrivá's life, evident from his youth, his habit of carrying a rosary, his ending homilies with Marian conversations, and his encouragement for images of the Virgin in Opus Dei centers. His book The Holy Rosary reflected his teaching on spiritual childhood and total abandonment to divine will.

Escrivá viewed the Mass as the "Source and summit of the Christian's interior life," a phrase later echoed by the Second Vatican Council. He diligently applied Vatican II's liturgical prescriptions within Opus Dei. Despite finding the transition to new rites difficult, especially missing traditional gestures, he forbade his followers from seeking dispensations, opting to show obedience. However, upon learning of Escrivá's struggles, Annibale Bugnini, Secretary of the Consilium for the Implementation of the Constitution on the Liturgy, granted him permission to celebrate Mass using the old rite privately, which he did only with a single Mass server present.

Theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, however, criticized Escrivá's spirituality as "insufficient" and his book The Way as "a little Spanish manual for advanced Boy Scouts," arguing that its prayer moves too much within the self and lacks contemplative depth. Journalist Kenneth L. Woodward similarly described Escrivá's writings as "unexceptional," "derivative," and revealing "a remarkable narrowness of mind, weariness of human sexuality, and artlessness of expression."

Escrivá taught that "joy has its roots in the form of a cross" and that "suffering is the touchstone of love," which he exemplified in his own life, including suffering from type 1 diabetes. He personally practiced corporal mortification and recommended it to others in Opus Dei. This included self-flagellation, a practice that has drawn controversy, with some testimonies describing him whipping himself so furiously that blood splattered on his cubicle walls. While self-mortification as penance has Catholic precedent, these specific practices and their intensity have been points of criticism. John Paul II, conversely, highlighted Escrivá's heroism during the Spanish Civil War, his abundant prayer and penance, and his response to public attacks with forgiveness, seeing them as sources of blessings for his apostolate's astonishing spread.

Controversially, Vladimir Felzmann, a former personal assistant to Escrivá, claimed that Escrivá was so distressed by Vatican II reforms that he contemplated integrating Opus Dei into the Greek Orthodox Church in 1967 or 1968, seeing the Catholic Church in "shambles." Felzmann stated Escrivá abandoned these plans as impracticable. This claim has been denied by Opus Dei officials, who state Escrivá's visit to Greece in 1966 was to explore organizing Opus Dei there, and that he had informed Vatican officials of his visit.

5. Character and Relationships

Josemaría Escrivá's character and relationships were perceived in vastly different ways, ranging from deeply dedicated and charismatic to vain and temperamental, reflecting a complex personality further complicated by family matters and political allegiances.

5.1. General Temperament and Public Perception

Josemaría Escrivá's character elicited varied perceptions from those who knew him. Bishop Leopoldo Eijo y Garay of Madrid, a close friend and confidant, described Escrivá as possessing "energy and his capacity for organization and government," along with an "ability to pass unnoticed." He praised Escrivá's obedience to Church hierarchy and his fervent love for the Church and the Roman Pontiff. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist and concentration camp survivor, noted Escrivá's "refreshing serenity," "unbelievable rhythm" of thought, and "amazing capacity" for connecting with people, stating he "lived totally in the present moment." Álvaro del Portillo, Escrivá's closest collaborator, emphasized his "dedication to God, and to all souls for God's sake; his constant readiness to correspond generously to the will of God." Pope Paul VI highlighted Escrivá's "extraordinariness" of sanctity, citing his abundant supernatural gifts and generous response to them. John L. Allen Jr., observing films of Escrivá, noted his "effervescence, his keen sense of humor," and ability to engage audiences spontaneously.

Conversely, critics presented a starkly different portrait. Spanish architect Miguel Fisac, an early Opus Dei member who parted ways with Escrivá, described him as pious but "vain, secretive, and ambitious," prone to "violent temper" in private, and exhibiting "little charity towards others or genuine concern for the poor." British journalist Giles Tremlett acknowledged these conflicting narratives, characterizing Escrivá as either "a loving, caring charismatic person or a mean-spirited, manipulative egoist." French historian Édouard de Blaye called him a "mixture of mysticism and ambition." María del Carmen Tapia, a former numerary who served as Escrivá's secretary for seven years, alleged that Escrivá often became angry, used abusive language, and that she was prevented from recording negative incidents. Tapia also claimed she was held captive in Opus Dei's Rome headquarters for several months in 1965-1966, "completely deprived of any outside contact." Despite such criticisms, some devotees and historians like Elizabeth Fox-Genovese highlight Opus Dei's "enviable record of educating the poor and supporting women."

5.2. Family Background and Name Changes

Josemaría Escrivá made several changes to his name during his lifetime, leading to controversy and differing interpretations. He was baptized José María Julián Mariano Escriba, but during his school days, he began spelling his surname with a "v" instead of a "b," becoming Escrivá. Critics such as Luis Carandell and Michael Walsh noted his adoption of the conjunction "y" (meaning "and") between his paternal and maternal surnames ("Escrivá y Albás"), a practice they claim was associated with aristocratic families, despite it being the legal naming format in Spain since 1870.

A particularly contentious change occurred in 1940, when Escrivá petitioned the Spanish government to change his surname to "Escrivá de Balaguer." He justified this request by stating that the name "Escrivá" was common on Spain's east coast and in Catalonia, causing "harmful and annoying confusion." In 1943, at the age of 41, the Barbastro cathedral registry and his baptismal certificate were annotated to reflect the change to "Escrivá de Balaguer." Balaguer is a town in Catalonia, the ancestral home of his paternal family. Critics, including former Opus Dei member Miguel Fisac, suggested that this change was motivated by a desire to distance himself from his father's bankrupt textile company and an "affection for the aristocracy." Fisac recounted that aristocratic visitors to the Foundation of Santa Isabel, where Escrivá served as chaplain, would inquire if he belonged to the noble Escrivá de Romaní family and would then ignore him upon learning he did not.

Conversely, his official biographer Andrés Vásquez de Prada and his younger brother Santiago Escrivá argued that the name change was an act of "fairness and loyalty" to his family. They explained that clerical and bureaucratic errors in transcribing the family name over generations had confused "b" and "v," which are pronounced similarly in Spanish. Supporters also maintained that adding "de Balaguer" was a common practice for Spanish families seeking to distinguish themselves from others with the same surname from different regions. Santiago also noted that Josemaría changed his first name from José María to the combined "Josemaría" around 1935, symbolizing his "single love for the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph." Santiago praised his brother's dedication to their family, recalling Josemaría's promise to care for them after their father's death and his obedience to their father's wish that he pursue a law doctorate, which enabled him to support the family through teaching.

5.3. Political Views and Stances on Governance

Josemaría Escrivá's political views and Opus Dei's alleged affiliations have been a consistent source of debate. Many of his contemporaries reported that Escrivá preached the virtue of patriotism, distinguishing it sharply from nationalism, which he viewed as a sin if it led to indifference or scorn towards other nations. He emphasized being "Catholic," meaning loving one's country while embracing the "noble aspirations of other lands."

However, critics have strongly linked Escrivá and Opus Dei to "National Catholicism" and the authoritarian regime of General Francisco Franco in Spain, particularly during and immediately after the Spanish Civil War. Catalan sociologist Joan Estruch argued that Escrivá was fundamentally "a child of his time," shaped by Francoist Spain and the Church of Pope Pius X. He contended that if Opus Dei had not "evolved," as Escrivá claimed it didn't need to, it would remain "a paramilitary, pro-fascist, antimodernist, integralist (reactionary) organization." Estruch cited the first edition of Escrivá's The Way, published in Valencia in 1939, which carried the dateline Año de la Victoria ("Year of the Victory"), referencing Franco's triumph. It also included a prologue by a pro-Franco bishop, Xavier Lauzurica, urging readers to become "perfect imitator[s] of Jesus Christ and a gentleman without blemish," so that "Spain will return to the old grandeur of its saints, wise men, and heroes." Escrivá also personally led a week-long spiritual retreat for General Franco and his family at the Royal Palace of El Pardo in April 1946.

Vittorio Messori describes the accusations of ties between Escrivá and Francoism as part of a "black legend." John Allen stated that Escrivá was neither explicitly "pro-Franco" (for which he was criticized for not praising Franco) nor "anti-Franco" (for which he was criticized for not being "pro-democracy"), asserting that no statement from Escrivá exists for or against Franco. Defenders, including German historian Peter Berglar, contend that Franco's Falangists actually suspected Escrivá of "internationalism, anti-Spainism and Freemasonry," and that Opus Dei and Escrivá were fiercely attacked by supporters of the new Spanish State, with Escrivá even being reported to the Tribunal for the Fight against Freemasonry.

In 1963, Swiss Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar strongly critiqued Escrivá's spirituality as "integralism," an attempt to impose spiritual values through worldly means, stating that despite claims of political freedom for its members, Opus Dei's "foundation is marked by Francoism." He later clarified in 1979 that he lacked "concrete information" to comment on Opus Dei at that time and found many criticisms "false and anti-clerical," though he maintained his negative judgment of Escrivá's spirituality in 1984.

In response to accusations of "integrism," Escrivá declared that "Opus Dei is neither on the left nor on the right nor in the centre" and that it "has never practised discrimination of any kind" regarding religious liberty. Opus Dei officials assert that individual members are free to choose their political affiliations, highlighting that members included figures who opposed Franco, such as writer Rafael Calvo Serer (forced into exile) and journalist Antonio Fontán (first president of the Senate after Spain's transition to democracy). Critics like Miguel Fisac and Damian Thompson, however, argued that Opus Dei consistently sought "advancement... of its interests" by courting those in power, regardless of coherent political ideology.

Opus Dei's alleged involvement in Latin American politics also generated controversy. American journalist Penny Lernoux linked the 1966 military coup in Argentina to Opus Dei, noting its leader, General Juan Carlos Onganía, attended an Opus Dei-sponsored spiritual retreat just before the coup. During his 1974 visit to Latin America, Escrivá visited Chile nine months after the 1973 coup that installed the right-wing military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. Escrivá declined a personal meeting with the Chilean government junta due to alleged illness but expressed in a letter his prayers for Chile, "especially when it found itself menaced by the scourge of the Marxist heresy." Critics charged that Opus Dei members supported Pinochet's coup and influenced Chile's economic "Miracle of Chile" in the 1980s, akin to the "technocrats" in Franco's Spain. However, only Joaquín Lavín has been unequivocally identified as an Opus Dei member among major right-wing politicians, while another member, Jorge Sabag Villalobos, belonged to a center-left party that opposed Pinochet. Historian Peter Berglar dismisses connections to fascist regimes as "gross slander," and Noam Friedlander calls allegations about Pinochet ties "unproven tales." Escrivá's collaborators asserted he despised dictatorships. Escrivá's Chilean visit and Opus Dei's growth there are sometimes cited as examples of Francoist influence in Chile.

6. Controversies and Criticisms

Josemaría Escrivá's legacy is marked by significant controversies and criticisms, particularly concerning his alleged political alignments, the acquisition of a noble title, and his relationships with other Catholic leaders, all of which continue to shape perceptions of his figure.

6.1. Allegations of Supporting Authoritarian Regimes

One of the most persistent and controversial accusations against Josemaría Escrivá and Opus Dei centers on their alleged support for far-right and authoritarian regimes, especially the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco in Spain, and involvement in other right-wing governments in Latin America.

6.1.1. Allegations of Hitler Defense

During Escrivá's beatification process, Vladimir Felzmann, a former personal assistant to Escrivá who later left Opus Dei, sent letters to Flavio Capucci, the postulator for Escrivá's cause. Felzmann claimed that around 1967 or 1968, Escrivá had remarked during a World War II movie, "Vlad, Hitler couldn't have been such a bad person. He couldn't have killed six million. It couldn't have been more than four million." Felzmann contextualized these remarks within the strong anti-communism prevalent in Spain, noting that in 1941, all male Opus Dei members (around fifty at the time) offered to join the "Blue Division" to fight against the Soviet Army on the Eastern Front. Another alleged quote attributed to Escrivá by critics is "Hitler against the Jews, Hitler against the Slavs, means Hitler against Communism."

Álvaro del Portillo, Escrivá's successor, strongly denied any claims that Escrivá endorsed Hitler, calling them "a patent falsehood" and part of a "slanderous campaign." Supporters and others have asserted that Escrivá regarded Hitler as a "pagan," a "racist," and a "tyrant."

6.1.2. Ties to Francoist Spain and Other Right-Wing Leaders

Escrivá and Opus Dei's relationship with the Franco regime in Spain remains highly controversial. After 1957, several Opus Dei members served as ministers in Franco's government, notably the "technocrats" who were instrumental in the "Spanish miracle" of the 1960s, including Alberto Ullastres, Mariano Navarro Rubio, Gregorio López-Bravo, Laureano López Rodó, Juan José Espinosa, and Faustino García-Moncó. Many of these individuals entered government under the patronage of Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco, who, while not an Opus Dei member, was reportedly sympathetic to the organization and increasingly controlled the Spanish government as Franco's health declined.

Journalist Luis Carandell claimed that upon the appointment of Ullastres and Navarro Rubio in 1957, Escrivá gleefully exclaimed, "They have made us ministers!"-a statement Opus Dei officially denies. On 23 May 1958, Escrivá sent a letter to Franco, expressing his joy as a priest and Spaniard that the "Chief of State's authoritative voice should proclaim that, 'The Spanish nation considers it a badge of honour to accept the law of God according to the one and true doctrine of the Holy Catholic Church, inseparable faith of the national conscience which will inspire its legislation.'" He further asked God to bestow "every sort felicity and impart abundant grace to carry out the grave mission entrusted to you."

The Swiss Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar criticized Escrivá's spirituality in 1963 as a form of "integrism", stating that despite Opus Dei's claims of political freedom, its foundation was "marked by Francoism." He later described Opus Dei as an "integrist concentration of power within the Church," aiming to impose spiritual objectives through "worldly means." However, von Balthasar distanced himself from these specific criticisms of Opus Dei as an organization in 1979, although he maintained his unfavorable judgment of Escrivá's spirituality in 1984.

In response, Escrivá asserted Opus Dei's political neutrality, stating it was "neither on the left nor on the right nor in the centre" and that it had always practiced non-discrimination regarding religious liberty. Opus Dei officials point out that its members are free to choose any political affiliation, including those who opposed Franco, such as writer Rafael Calvo Serer and journalist Antonio Fontán, the first president of the Senate after Spain's transition to democracy. John Allen concluded that Escrivá was neither anti-Franco nor pro-Franco. Nevertheless, critics like Miguel Fisac and Damian Thompson argued that Opus Dei consistently sought to advance its interests and influence by courting powerful figures, without adhering to a consistent political ideology.

The alleged involvement of Opus Dei in Latin American politics has also been a contentious issue. American journalist Penny Lernoux claimed the 1966 military coup in Argentina occurred shortly after its leader, General Juan Carlos Onganía, attended an Opus Dei-sponsored spiritual retreat. In 1974, Escrivá visited Chile nine months after the 1973 coup that overthrew Salvador Allende and installed Augusto Pinochet's military dictatorship. Although Escrivá declined a personal meeting with the Chilean government junta due to illness, he wrote to its members, expressing his fervent prayers for Chile, "especially when it found itself menaced by the scourge of the Marxist heresy."

Critics charged that Opus Dei members supported Pinochet's coup and played a role in Chile's economic "Miracle of Chile" in the 1980s, mirroring the "technocrats" in Francoist Spain. While most major right-wing politicians were not members, Joaquín Lavín has been unequivocally identified as an Opus Dei member, while another, Jorge Sabag Villalobos, belonged to a center-left party that opposed Pinochet's regime. German historian Peter Berglar dismissed connections between Opus Dei and fascist regimes as "gross slander," and journalist Noam Friedlander called such allegations "unproven tales." Escrivá's collaborators maintained he despised dictatorships. However, Escrivá's visit to Chile and Opus Dei's subsequent growth there have been cited by some historians as evidence of a broader influence from Francoist Spain in Chile.

6.2. Controversy Regarding Noble Title

Another point of controversy surrounding Escrivá was his request and subsequent acquisition of the noble title of Marquess of Peralta in 1968 from the Spanish Ministry of Justice. This action stirred debate due to its apparent conflict with the humility expected of a Catholic priest, and because the same title had been previously rehabilitated in 1883 by Pope Leo XIII and King Alfonso XII of Spain for a Costa Rican diplomat, Manuel María de Peralta y Alfaro, to whom Escrivá had no direct male-line family connection. The earlier rehabilitation documents specified the title was granted in 1738 (not 1718) to Juan Tomás de Peralta y Franco de Medina by Archduke Charles of Austria as Holy Roman Emperor, not as a pretender to the Spanish throne. Ambassador Peralta died without children in 1930, and his Costa Rican kin did not request the title's transmission, with one even publishing a genealogical study seemingly contradicting Escrivá's claim.

Escrivá did not publicly use the title and transferred it to his younger brother, Santiago, in 1972. Santiago defended the act as "heroic," stating Josemaría knew he would be "vilified" but did it for his family's benefit, never intending to use the title himself. However, this justification is complicated by Santiago's own unsuccessful attempt in 1968 to rehabilitate a different noble title, the barony of San Felipe. Historian Ricardo de la Cierva (a former Spanish Minister of Culture) and architect Miguel Fisac (a former Opus Dei member close to Escrivá) suggested that Escrivá's pursuit of the marquessate might have been part of an unsuccessful attempt to gain influence or control within the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), a Catholic religious order whose leading members were required to be of noble birth, and to which Escrivá's deputy, Álvaro del Portillo, already belonged. De la Cierva concluded that while Escrivá's desire for the title was understandable, the "falsification" upon which it was based was "extremely sad and even extremely grave."

6.3. Relations with Other Catholic Leaders

Josemaría Escrivá's relationships with other Catholic officials were reportedly fraught with tensions and disagreements. Church historian Giancarlo Rocca stated that Escrivá actively sought the rank of bishop but was twice refused by the Roman Curia, in 1945 and again in 1950, over concerns about Opus Dei's organization and Escrivá's psychological profile.

Sociologist Alberto Moncada, a former Opus Dei member, collected testimonies regarding Escrivá's difficult relations with other Church figures. Antonio Pérez-Tenessa, former secretary general of Opus Dei in Rome, reported Escrivá's intense displeasure at the election of Pope Paul VI in 1963 and private doubts about the Pope's salvation. María del Carmen Tapia, who worked with Escrivá in Rome, claimed he had "no respect" for Popes Pope John XXIII or Paul VI and believed Opus Dei was "above the Church in holiness."

Luigi de Magistris, then regent of the Vatican's Apostolic Penitentiary, confidentially requested the suspension of Escrivá's beatification in 1989, noting "serious tensions" between Escrivá and the Jesuits. He alluded to Escrivá distancing himself from his former Jesuit confessor, Valentino Sánchez, due to Jesuit opposition to Opus Dei's proposed constitutions. Journalist Luis Carandell stated Escrivá kept such a distance from the Jesuit Superior General, Pedro Arrupe, that Arrupe once joked about doubting Escrivá's existence.

According to Alberto Moncada, a significant portion of Escrivá's years in Rome was dedicated to campaigning for Opus Dei's independence from diocesan bishops and the Vatican curia. This autonomy was ultimately achieved after Escrivá's death when Pope John Paul II established Opus Dei as a personal prelature in 1982, making it subject only to its own prelate and the Pope. Opus Dei currently remains the sole personal prelature in the Catholic Church, a juridical figure intended by the Second Vatican Council to offer pastoral care tailored to the faithful's specific needs. Its work is meant to complement dioceses, sometimes collaborating directly, such as when Opus Dei priests assume pastoral care of parishes at the request of local bishops. Escrivá himself stated, "The only ambition, the only desire of Opus Dei and each of its members is to serve the Church as the Church wants to be served, within the specific vocation God has given us." Membership in the prelature does not exempt Catholics from the authority of their local diocesan bishop.

7. Beatification and Canonization Process

The beatification and canonization of Josemaría Escrivá were notable for their rapidity and generated significant debate and criticism regarding their procedural aspects and alleged irregularities.

7.1. Official Procedures and Recognized Miracles

Following Escrivá's death on 26 June 1975, the Postulation for his cause of beatification and canonization received an unprecedented number of testimonies and petitions from around the world, including letters from 69 cardinals and one-third of the world's bishops (approximately 1,300). The cause was officially opened in Rome on 19 February 1981, and approved by Pope John Paul II on 5 February 1981. Investigative procedures were conducted in Rome and Madrid between 1981 and 1986 to gather information on his life, virtues, and miracles.

The first official miracle attributed to Escrivá's intercession was reported on 19 February 1981: the instantaneous cure in 1976 of Sister Concepción Boullón Rubio from lipomatosis, a rare disease, after her family prayed to Escrivá. On 9 April 1990, Pope John Paul II recognized Escrivá's Christian virtues to a "heroic degree," declaring him Venerable. On 6 July 1991, the Board of Physicians for the Congregation for the Causes of Saints unanimously accepted Sister Rubio's cure as scientifically inexplicable. Consequently, he was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 17 May 1992, becoming Blessed Josemaría Escrivá.

A second miraculous cure was reported on 15 March 1993: the healing of Dr. Manuel Nevado Rey from cancerous chronic radiodermatitis, an incurable disease, in November 1992. This miracle, attributed to Escrivá's intercession, was validated by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints and approved by Pope John Paul II in December 2001, clearing the way for his canonization. Pope John Paul II, a vocal supporter of Opus Dei, canonized Escrivá as a saint on 6 October 2002. The canonization Mass was attended by 42 cardinals, 470 bishops, and representatives from numerous religious orders and Catholic groups. Church officials at the time emphasized the enduring relevance of Escrivá's message on the universal call to holiness through daily work, describing it as an "inexhaustible source of spiritual light." By the year of his canonization, the Opus Dei prelate reported 48 unexplained medical favors and 100,000 ordinary favors attributed to Escrivá's intercession.

7.2. Criticisms of the Process

Escrivá's beatification and canonization processes attracted an unusual amount of attention and criticism, both within the Catholic Church and from the press, with critics questioning the rapidity and procedural fairness of his path to sainthood.

7.2.1. Rapid Process and Procedural Allegations

Critics widely questioned the speed of Escrivá's canonization. Journalist William D. Montalbano described it as "perhaps the most contentious beatification in modern times" on the eve of his 1992 beatification. Critics argued the process was riddled with irregularities. However, supporters, like Augustinian priest Rafael Pérez, who presided over the Madrid tribunal for Escrivá's cause, defended the speed, citing Escrivá's "universal importance" and the streamlined procedures introduced by the 1983 Code of Canon Law which simplified canonization processes to present "models who lived in a world like ours." Flavio Capucci, the postulator, also noted the "earnestness" of 6,000 petitions to the Vatican. While Escrivá was beatified 17 years after his death, Mother Teresa was canonized even faster, just 6 years after her death.

Journalist Kenneth L. Woodward reported that the 6,000-page official document supporting Escrivá's sainthood, the positio, was declared confidential but leaked in 1992. He claimed that approximately 40% of the 2,000 pages of testimonies came from Álvaro del Portillo and Javier Echevarría Rodríguez, Escrivá's successors at the head of Opus Dei, who critics argued had vested interests. The only critical testimony quoted in the positio was a mere two pages from Alberto Moncada, a Spanish sociologist and former Opus Dei member who had limited personal contact with Escrivá and had left the Catholic Church, making his testimony easier for Church authorities to dismiss.

Critics also raised concerns that some physicians who authenticated the "scientifically inexplicable cures" attributed to Escrivá, such as Dr. Raffaello Cortesini (a heart surgeon), were themselves members of Opus Dei. The Vatican affirmed that its Medical Consultants for the Congregation unanimously found Dr. Manuel Nevado Rey's cure from cancerous chronic radiodermatitis to be "very quick, complete, lasting and scientifically inexplicable," with theological consultants also unanimously attributing it to Escrivá.

Several former Opus Dei members who were critical of Escrivá's character claimed they were denied a hearing during the beatification and canonization processes. These included Miguel Fisac (Spanish architect), Vladimir Felzmann (Escrivá's personal assistant), María del Carmen Tapia (worked with Escrivá in Rome), Carlos Albás (Escrivá's first cousin once removed), María Angustias Moreno (Opus Dei official), and John Roche (Irish physicist). Groups formed by former members, such as the Opus Dei Awareness Network (ODAN) and "OpusLibros," continue to oppose Opus Dei and its practices. Woodward asserted he interviewed six former associates who provided examples of Escrivá's "vanity, venality, temper tantrums, harshness toward subordinates, and criticism of popes and other churchmen," but their testimony was not allowed. He added that at least two were "vilified in the positio by name" without being permitted to defend themselves.

Catholic theologian Richard McBrien called Escrivá's sainthood "the most blatant example of a politicized [canonization] in modern times." However, Catholic writer John Allen contended that these views are countered by numerous other former and current members and the hundreds of thousands who participate in Opus Dei activities, suggesting that interpretations of the facts depend on one's "basic approach to spirituality, family life, and the implications of a religious vocation." Allen's own account of Opus Dei has also faced scrutiny for its impartiality.

7.2.2. Reports of Discord Among Judges

Josemaría Escrivá's canonization generated unusual attention and criticism, including reports of discord among the judges involved. Flavio Capucci, Escrivá's postulator, summarized the main accusations against Escrivá: having a bad temper, being cruel and vain, close to Francisco Franco, pro-Nazism, and so dismayed by the Second Vatican Council that he considered converting to the Eastern Orthodox Church.

A Newsweek article by Woodward reported that two of the nine judges of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints overseeing Escrivá's beatification had requested a suspension of the proceedings. These dissenters were identified as Luigi de Magistris, a prelate in the Vatican's Apostolic Penitentiary, and Justo Fernández Alonso, rector of the Spanish National Church in Rome. According to Woodward, one dissenter wrote that Escrivá's beatification could cause the Church "grave public scandal." Cardinal Silvio Oddi also was quoted stating that many bishops were "very displeased" with the rapid canonization process so soon after Escrivá's death. However, José Saraiva Martins, Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, denied awareness of such dissent.

The journal Il Regno published in May 1992 the confidential vote of one of the dissenting judges, asking for the process's suspension. This document, dated August 1989, questioned the haste of the proceedings, the near absence of critical testimonies, the failure to address issues regarding Escrivá's relations with the Franco regime and other Catholic organizations, and suggestions from official testimonies that Escrivá lacked proper spiritual humility. While the judge's name was not disclosed, the document's content, particularly the mention of meeting Escrivá briefly in 1966 while serving as a notary for the Holy Office, implied the author was De Magistris.

De Magistris also argued that the testimony of Álvaro del Portillo, Opus Dei's director and Escrivá's confessor for 31 years, should have been entirely excluded due to the inviolability of the Seal of the Confessional in the Catholic Church. John Allen Jr. noted that some observers believed De Magistris was punished for his opposition to Escrivá's canonization. De Magistris was promoted to head the Apostolic Penitentiary in 2001, a position typically held by a cardinal, but Pope John Paul II did not elevate him to cardinal and replaced him within two years, effectively forcing his retirement. However, Pope Francis's decision to make De Magistris a cardinal in 2015, shortly before his 89th birthday (making him ineligible to participate in papal conclaves), was interpreted by some as a consolation for his earlier treatment.

8. Legacy and Influence

Josemaría Escrivá's enduring impact on the Catholic Church and Christian spirituality is a subject of diverse evaluations, marked by both strong endorsements and critical assessments, while his memory is preserved through various commemorative sites and institutions.

8.1. Diverse Evaluations and Endorsements

The significance of Josemaría Escrivá's message and teachings has been a subject of considerable debate within and outside Catholic circles. French Protestant historian Pierre Chaunu, a professor at the Sorbonne, predicted that Escrivá's work "will undoubtedly mark the 21st century." Conversely, the Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar dismissed Escrivá's seminal work, The Way, as "a little Spanish manual for advanced Boy Scouts," arguing its spirituality was insufficient to sustain a major religious organization. However, the monk and spiritual writer Thomas Merton believed the book would "certainly do a great deal of good by its simplicity."

Critics of Opus Dei have often asserted that the intellectual originality and importance of Escrivá's theological, historical, and legal contributions have been greatly exaggerated by his followers. Nevertheless, many Catholic Church officials have highly praised Escrivá's influence and the relevance of his teachings. Cardinal Ugo Poletti, in the 1981 decree introducing Escrivá's cause for beatification, recognized him as a "precursor" of the Church's teaching on the universal call to holiness, a message of "such fruitfulness in the life of the Church." Sebastiano Baggio, Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops, stated a month after Escrivá's death that his life, works, and message constituted "a turning point, or more exactly a new original chapter in the history of Christian spirituality." A Vatican peritus (consultor) for the beatification process described him as "a figure from the deepest spiritual sources." Franz König, Archbishop of Vienna, wrote in 1975 that Opus Dei's "magnetic force" likely stemmed from its "profoundly lay spirituality," noting that Escrivá "anticipated the great themes of the Church's pastoral action in the dawn of the third millennium of her history." American theologian William May emphasized that the "absolutely central" part of Escrivá's teaching is that "sanctification is possible only because of the grace of God... and it consists essentially in an intimate, loving union with Jesus."

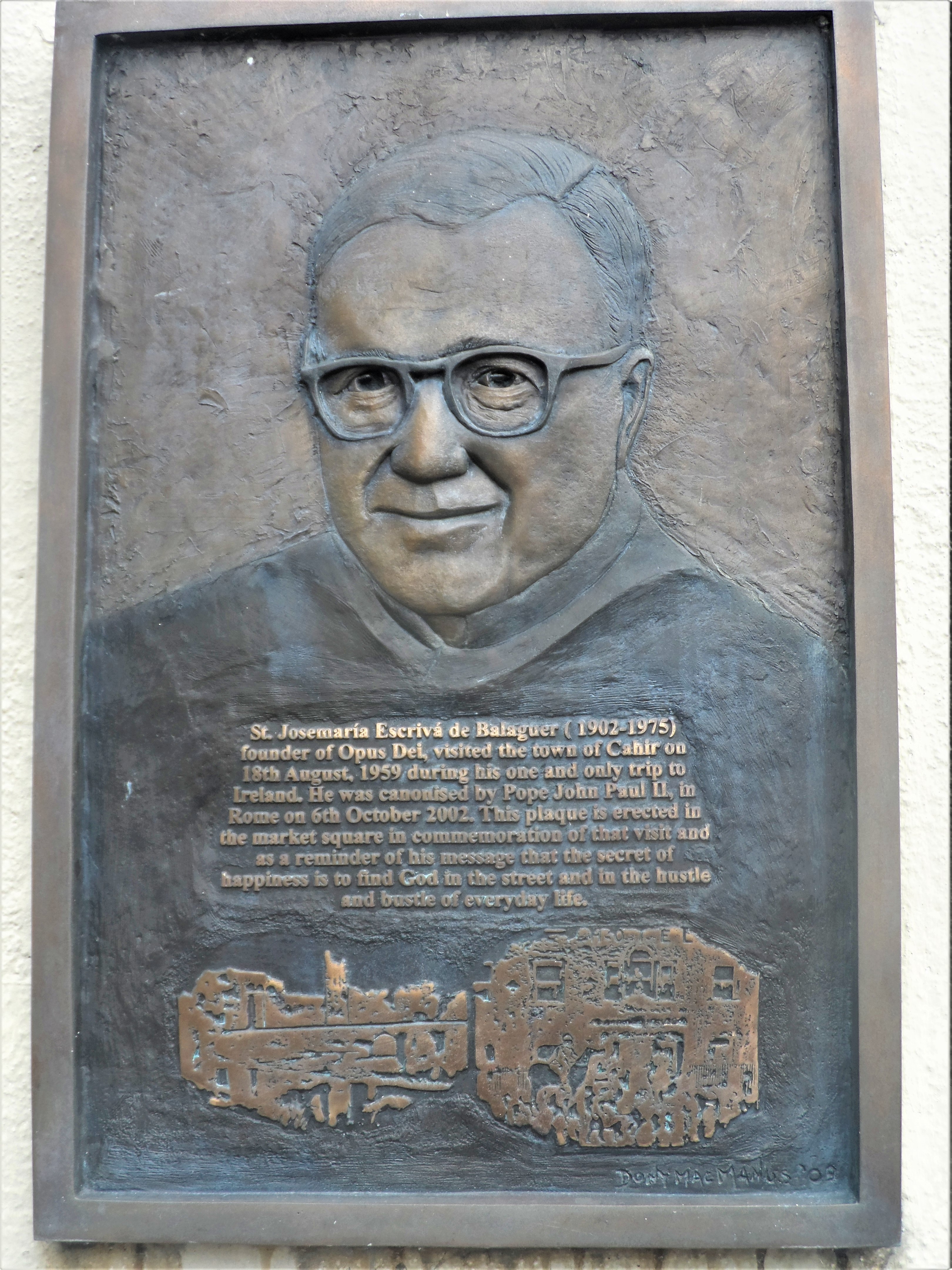

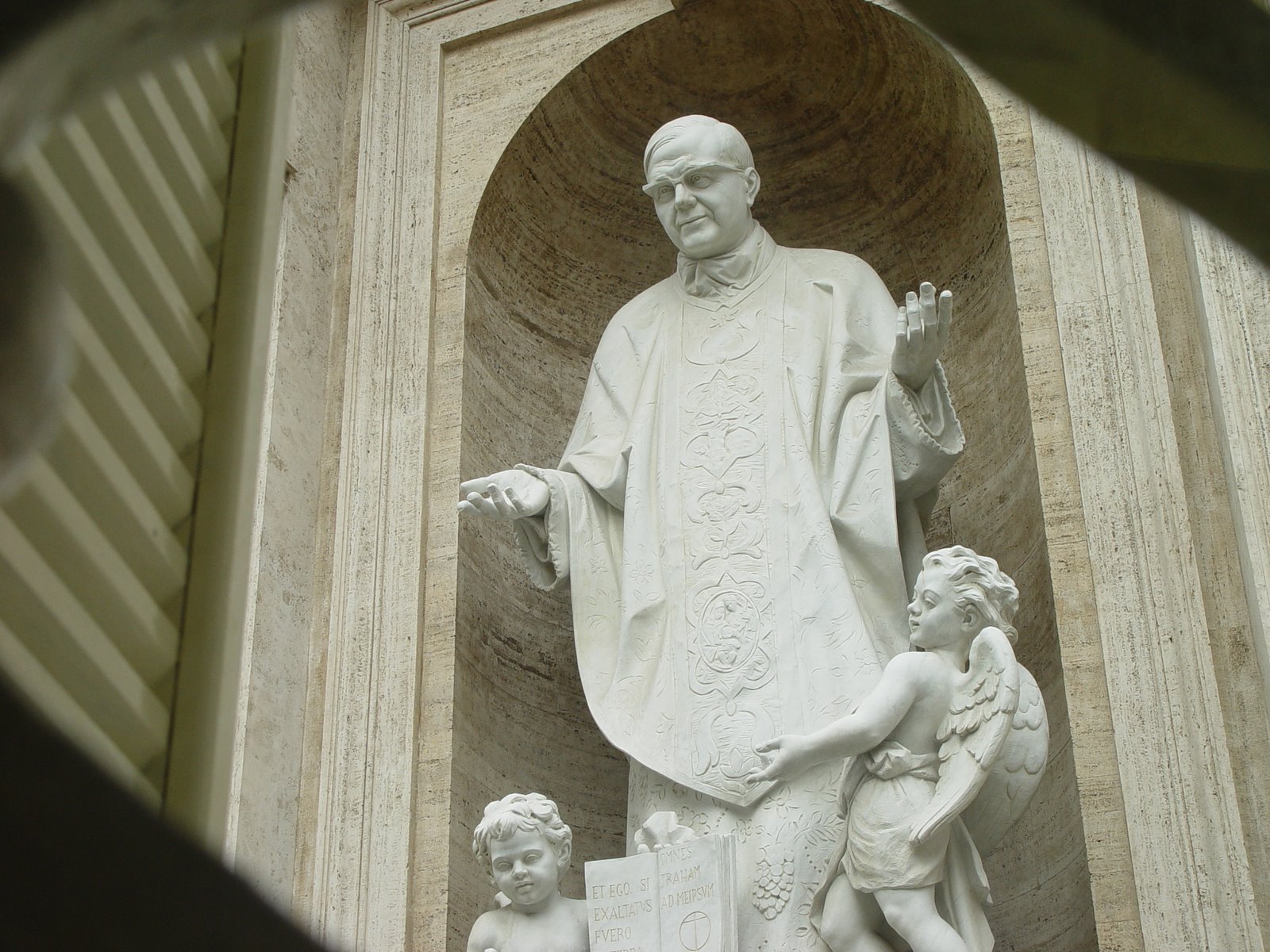

8.2. Memorials and Commemorative Sites

Significant memorials and commemorative sites have been established to honor Josemaría Escrivá's memory and perpetuate his teachings. The most prominent of these is the Torreciudad shrine in Spain, which he actively promoted and oversaw the construction of in his later years. Inaugurated shortly after his death, it serves as a major pilgrimage site and the spiritual heart of Opus Dei. In 2005, a 16 ft (5 m)-tall bronze sculpture of Saint Josemaría, created by Romano Cosci, was installed on an exterior wall of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City. This placement was directed by Pope John Paul II, who desired to have statues of modern saints on the basilica's exterior. The statue was blessed by Pope Benedict XVI. Other institutions, such as the University of Navarre in Spain and the University of Piura in Peru, founded with his initiative, also stand as a testament to his commitment to education and spiritual formation. Additionally, schools like Nagasaki Seido Elementary and Junior High School and Seido Mikawadai Elementary, Junior High, and High School in Nagasaki, Japan, were established with his encouragement, further extending his educational legacy.

9. Writings

Josemaría Escrivá's major published works articulate his core teachings, emphasizing the call to holiness in everyday life. These books, translated into numerous languages, continue to be widely read.

- The Way

- Furrow

- The Forge

- Conversations with Monsignor Josemaría Escrivá

- Friends of God

- Christ Is Passing by

- In Love with the Church

- Holy Rosary

- The Way of the Cross

- The Odour of Christ