1. Early life and background, 1912-1945

James Callaghan's formative years were deeply shaped by his working-class origins and early experiences with public service and trade unionism. These experiences laid the groundwork for his future political career and his commitment to social welfare.

1.1. Birth and family

Leonard James Callaghan was born on 27 March 1912, at 38 Funtington Road, Copnor, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. He adopted his middle name, James, from his father, James Callaghan (1877-1921). His paternal grandfather was an Irish Catholic who had immigrated to England during the Great Irish Famine, and his paternal grandmother was Elizabeth Bernstein, a Jewish woman from Sheffield. Callaghan's father ran away from home in the 1890s to join the Royal Navy; to conceal his true identity and age, he used a false birth date and changed his surname from Garogher to Callaghan. He served in the Navy, including during the Battle of Jutland in 1916, and rose to the rank of Chief Petty Officer.

His mother was Charlotte Gertrude Callaghan (née Cundy, 1879-1961), an English Baptist. Due to the Catholic Church's refusal at the time to marry Catholics to members of other denominations, James Callaghan senior abandoned Catholicism and married Charlotte in a Baptist chapel. James and Charlotte had an elder child, Dorothy Gertrude Callaghan (1904-1982). After being demobilized from the Navy in 1919, Callaghan's father joined the Coastguard, and the family relocated to Brixham, Devon. However, he tragically died of a heart attack in 1921 at the age of 44, when Callaghan was only nine years old. This left the family without an income and dependent on charity. Their financial situation significantly improved in 1924 when the first Labour government was elected, introducing changes that granted his mother a widow's pension of ten shillings a week, acknowledging his father's death was partly attributable to his war service.

1.2. Education and early career

In his early life, Callaghan was primarily known by his first name, Leonard. He chose to be known by his middle name, James, or simply Jim, upon entering politics in 1945. He received his education at Portsmouth Northern Secondary School, where he earned the Senior Oxford Certificate in 1929. Unable to afford university education, he instead pursued a career in the Civil Service by sitting the entrance exam.

At the age of 17, Callaghan began working as a clerk for the Inland Revenue at Maidstone in Kent. During his time there, he became involved in the local Labour Party branch and the Association of the Officers of Taxes (AOT), a trade union for civil servants in that department. Within a year, he became the office secretary of the union. In 1932, he passed a Civil Service examination, advancing to a senior tax officer position, and in the same year, he became the Kent branch secretary of the AOT. The following year, he was elected to the AOT's national executive council. In 1934, he was transferred to Inland Revenue offices in London. Following a merger of unions in 1936, Callaghan was appointed a full-time union official, becoming the assistant secretary of the Inland Revenue Staff Federation (IRSF), and consequently resigned from his civil service duties.

1.3. Trade union activities

Callaghan's full-time role with the Inland Revenue Staff Federation (IRSF) was pivotal in shaping his political future. This position brought him into contact with prominent figures such as Harold Laski, the Chairman of the Labour Party's National Executive Committee and a respected academic at the London School of Economics. Laski recognized Callaghan's potential and encouraged him to stand for Parliament, even repeatedly requesting that Callaghan study and lecture at the LSE. It was also during his time working in the Inland Revenue in the early 1930s that Callaghan met Audrey Moulton, whom he married in July 1938 in Maidstone.

1.4. War service

Following the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Callaghan sought to join the Royal Navy in 1940. Initially, his application was declined because his role as a trade union official was deemed a reserved occupation. However, he was finally permitted to join the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve as an Ordinary Seaman in 1942. During his training for promotion, a medical examination revealed he was suffering from tuberculosis, leading to his admission to the Royal Naval Hospital Haslar in Gosport, near Portsmouth.

After recovering, he was discharged from active service and assigned to duties with the British Admiralty in Whitehall. He worked in the Japanese section, where he authored a service manual for the Royal Navy titled The Enemy: Japan. He subsequently served with the East Indies Fleet aboard the escort carrier HMS Activity. In April 1944, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant. Callaghan remains the last British prime minister to have been an armed forces veteran and the only one ever to have served in the Royal Navy.

While on leave from the Navy, Callaghan was selected as a Parliamentary candidate for Cardiff South. He secured the local party ballot by a narrow margin of twelve votes against George Thomas, who received eleven votes. His selection for the Cardiff South seat was greatly encouraged by his friend Dai Kneath, a member of the IRSF National Executive from Swansea, who had connections with the local Labour Party secretary, Bill Headon. By 1945, Callaghan was serving on HMS Queen Elizabeth in the Indian Ocean. Following VE Day, he returned to the United Kingdom, alongside other prospective candidates, to participate in the upcoming general election.

2. Entry into Parliament and early political career (1945-1964)

James Callaghan's entry into Parliament marked the beginning of a distinguished political career that would see him serve for over four decades. His early years as an MP involved active participation in the Attlee government and a growing influence within the Labour Party during its subsequent period in opposition.

2.1. Attlee government service (1947-1951)

The 1945 United Kingdom general election resulted in a landslide victory for the Labour Party, bringing Clement Attlee to power and forming the first-ever majority Labour government. On 26 July 1945, Callaghan successfully won his Cardiff South seat, defeating the incumbent Conservative MP, Sir Arthur Evans, by a substantial margin of 17,489 votes to 11,545. He campaigned on key issues such as the swift demobilisation of the armed forces and the implementation of a new housing construction programme.

Initially, Callaghan was considered to be on the left wing of the Labour Party. In 1945, he notably joined 22 other rebel MPs in voting against accepting the Anglo-American loan. While he did not join the "Keep Left" group of left-wing Labour MPs, he did co-sign a letter in 1947 with 20 other members, advocating for a 'socialist foreign policy' that would offer an alternative to the capitalism of the United States and the totalitarianism of the USSR.

In October 1947, Callaghan received his first junior government appointment as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport, serving under Alfred Barnes. In this role, Callaghan was responsible for enhancing road safety. His notable achievements included persuading the government to introduce zebra crossings and to expand the use of cat's eyes on trunk roads. Although he did not oppose the government's use of emergency powers to break dockers' strikes in both 1948 and 1949, he empathised with the ordinary dockers' concerns and communicated his protest to Attlee regarding the operation of the Dock Labour Scheme.

In February 1950, he was transferred to the Admiralty as Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to the Admiralty. In this capacity, he served as a delegate to the Council of Europe, where he supported proposals for economic co-operation but firmly resisted plans for a unified European army. With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Callaghan was tasked with overseeing the expenditure of funds allocated to the Royal Navy for rearmament.

2.2. Opposition years (1951-1964)

Following Labour's defeat in the 1951 United Kingdom general election, Callaghan remained a prominent figure within the party. Popular among Labour MPs, he was elected to the Shadow Cabinet, a position he would hold for the next 29 years, whether in opposition or government. During this period, he became associated with the Gaitskellite wing on the Labour right, though he deliberately avoided aligning himself too strongly with any particular faction.

He served as the Labour spokesman on Transport (1951-1953), Fuel and Power (1953-1955), Colonial Affairs (1956-1961), and Shadow Chancellor (1961-1964). Between 1955 and 1960, he also served as a parliamentary advisor to the Police Federation, where he successfully negotiated a pay increase for police officers. In 1960, he unsuccessfully ran for the Deputy Leadership of the party, opposing nuclear disarmament. Despite George Brown, another candidate from the Labour right, agreeing with him on this policy, Callaghan managed to force Brown into a second ballot.

When Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour Party leader, unexpectedly died in January 1963, Callaghan ran to succeed him in the leadership contest. Despite gaining support from some on the right who wished to prevent Harold Wilson from becoming leader, Callaghan finished third, and Wilson ultimately won the leadership.

3. Key ministerial roles under Harold Wilson (1964-1976)

Under the premiership of Harold Wilson, James Callaghan held three of the most significant governmental positions, grappling with major economic, social, and foreign policy challenges that defined British politics in the 1960s and 1970s.

3.1. Chancellor of the Exchequer (1964-1967)

In October 1964, following Labour's narrow victory in the 1964 United Kingdom general election, Harold Wilson appointed Callaghan as the new Chancellor of the Exchequer. Callaghan's tenure coincided with a tumultuous period for the British economy. The previous Conservative government's fiscally expansionary measures had led to a pre-election economic boom, causing imports to outpace exports significantly. As a result, the incoming Labour government faced a chronic balance of payments deficit of £800.00 M GBP and immediate speculative attacks on sterling, whose exchange rate was fixed by the Bretton Woods system. Both Wilson and Callaghan were vehemently opposed to devaluation, fearing a repeat of the political fallout from the previous Labour government's 1949 devaluation. The alternative was a series of austerity measures aimed at reducing domestic demand and stabilising the currency.

Just ten days into his role, Callaghan introduced a 15% surcharge on imports, excluding foodstuffs and raw materials, to address the deficit. This measure provoked international outcry, forcing the government to declare it temporary, a decision Callaghan later admitted he mishandled due to haste. On 11 November, his first budget increased income tax and petrol tax and introduced a new capital gains tax, measures economists deemed necessary to cool the economy. However, social provisions like increased state and widow's pensions, promised in Labour's manifesto, were disliked by financial markets, causing a further run on the pound. On 23 November, the bank rate was raised sharply from 2% to 7%, drawing significant criticism. The situation was complicated by the Governor of the Bank of England, Lord Cromer, who opposed the government's fiscal policies. Only after Callaghan and Wilson threatened a new general election did Cromer secure a £3.00 B GBP loan to stabilise reserves.

Callaghan's second budget on 6 April 1965 sought to deflate the economy and reduce import demand by £250.00 M GBP. The bank rate was soon lowered to 6%, bringing a brief period of stability. In June, Callaghan visited the United States to discuss the British economy with President Lyndon B. Johnson and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). By July, the pound was again under pressure, compelling Callaghan to implement severe temporary measures, including delaying government building projects and postponing new pension plans, to demonstrate control. He and Wilson remained resolute against floating or devaluing the pound.

The government continued to struggle with the economy and a slim parliamentary majority, which by 1966 had dwindled to one. On 28 February, Wilson called a general election for 31 March 1966. The next day, Callaghan presented a 'little budget' to the Commons, making the historic announcement that the UK would adopt decimal currency, though its implementation would not occur until 1971 under a Conservative government. He also introduced a short-term mortgage scheme for low-wage earners. In the 1966 United Kingdom general election, Labour secured a significantly increased majority of 97 seats.

On 4 May, Callaghan introduced his next budget, notably featuring the Selective Employment Tax, which aimed to favour the manufacturing industry over the service sector. Twelve days later, a national dock strike, following a national strike by the National Union of Seamen, exacerbated sterling's problems. A £3.30 B GBP loan from Swiss banks was approaching its repayment deadline. On 14 July, the bank rate was raised again to 7%, and on 20 July, Callaghan announced a ten-point emergency package, including further tax increases and a six-month wage freeze. By early 1967, the economy showed signs of stabilisation, with the balance of payments nearing equilibrium, allowing the bank rate to be reduced to 6% in March and 5.5% in May. It was under these improving conditions that Callaghan successfully beat Michael Foot in a vote to become Treasurer of the Labour Party.

However, economic turmoil resumed in June with the Six-Day War in the Middle East. Several Arab countries, including Kuwait and Iraq, imposed an oil embargo against Britain, accusing it of supporting Israel, leading to a disastrous rise in oil prices that severely impacted the balance of payments. In mid-September, an eight-week national dock strike further crippled the economy. The final blow came with an EEC report suggesting the pound could not be sustained as a reserve currency, renewing calls for devaluation. Callaghan countered that without the Middle East crisis, Britain would have achieved a balance of payments surplus. Nevertheless, rumours of impending devaluation triggered heavy selling of sterling on world markets.

Callaghan privately confessed to Wilson that he doubted the pound could be saved, a view reinforced by Alec Cairncross, head of the Government Economic Service, who advised immediate devaluation. Despite the IMF offering a $3 billion contingency fund (which Wilson and Callaghan rejected due to intrusive conditions), the historic decision was made on 15 November to devalue the pound by 14.3%, from its fixed exchange rate of $2.80 to $2.40. The public announcement was scheduled for the 18th. However, during a House of Commons question session, Callaghan faced a difficult situation. In response to a backbencher's question, he stated he did not comment on rumours. When pressed by Stan Orme on whether devaluation was preferable to deflation, Callaghan replied he had "nothing to add or subtract from, anything I have said on previous occasions on the subject of devaluation." Speculators interpreted this as a confirmation of devaluation, leading to massive selling of sterling and costing the country £1.50 B GBP in the subsequent 24 hours. This incident caused a significant political controversy. Immediately, Callaghan offered his resignation as Chancellor, which Wilson accepted due to mounting political pressure. Wilson then moved Roy Jenkins, the Home Secretary, to Chancellor, and Callaghan became the new Home Secretary on 30 November 1967.

3.2. Home Secretary (1967-1970)

As Home Secretary, Callaghan confronted sensitive issues concerning race relations, immigration, and the burgeoning conflict in Northern Ireland. His background in the trade union movement also influenced his stance on proposed labour reforms.

He was responsible for the highly controversial Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968. This legislation was prompted by Conservative fears of an imminent influx of Kenyan Asians into the country. The bill passed through the Commons in just a week, establishing a new system of entry controls for holders of British passports who lacked a "substantial connection" with Britain. In his autobiography Time and Chance, Callaghan stated that while introducing the bill was an unwelcome task, he did not regret it. He explained that the Asians had "discovered a loophole" and told a BBC interviewer, "Public opinion in this country was extremely agitated, and the consideration that was in my mind was how we could preserve a proper sense of order in this country and, at the same time, do justice to these people-I had to balance both considerations." Conversely, Conservative MP Ian Gilmour, an opponent of the Act, argued it was "brought in to keep the blacks out."

In the same year, the significant Race Relations Act 1968 was passed, making it illegal to refuse employment, housing, or education based on ethnic background. This Act expanded the powers of the Race Relations Board to handle discrimination complaints and established a new supervisory body, the Community Relations Commission, to foster "harmonious community relations." Presenting the bill to Parliament, Callaghan emphasised its gravity, stating, "The House has rarely faced an issue of greater social significance for our country and our children."

Callaghan's term as Home Secretary was also profoundly shaped by the escalating conflict in Northern Ireland. Despite the long-standing British government policy of non-intervention in Northern Irish affairs, the severe sectarian violence between the province's Protestant and Catholic communities in August 1969 left the Government of Northern Ireland with no option but to request direct British intervention. As Home Secretary, Callaghan made the pivotal decision to deploy British Army troops to the province. In return for military support, Callaghan and Wilson demanded that the Northern Ireland government implement various reforms. These included the phasing out of the Protestant paramilitary B-Specials and their replacement by the Ulster Defence Regiment, which was open to Catholic recruits. Additionally, reforms aimed at reducing discrimination against Catholics were sought, such as changes to the voting franchise and local government boundaries, as well as reforms in housing allocations. Although British troops were initially welcomed by Northern Ireland's Catholics, public sentiment soured by early 1970, leading to the emergence of the Provisional IRA and the start of what became decades of violence known as The Troubles.

In 1969, Callaghan, a staunch advocate for the Labour-trade union link, successfully led the opposition within a divided Cabinet against Barbara Castle's White Paper "In Place of Strife", which aimed to reform trade union law. Among its proposals were plans to mandate a ballot before a strike and the creation of an Industrial Board to enforce settlements in industrial disputes. This action, a decade later, would contribute to the challenges Callaghan faced during the "Winter of Discontent".

From 1970 to 1974, during Labour's time in opposition following their unexpected defeat to Edward Heath in the 1970 United Kingdom general election, Callaghan served first as Shadow Home Secretary and then as Shadow Foreign Secretary. In 1973, he agreed to be considered for the position of Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), following an approach from Conservative Chancellor Anthony Barber. However, his candidacy was ultimately vetoed by the French government.

3.3. Foreign Secretary (1974-1976)

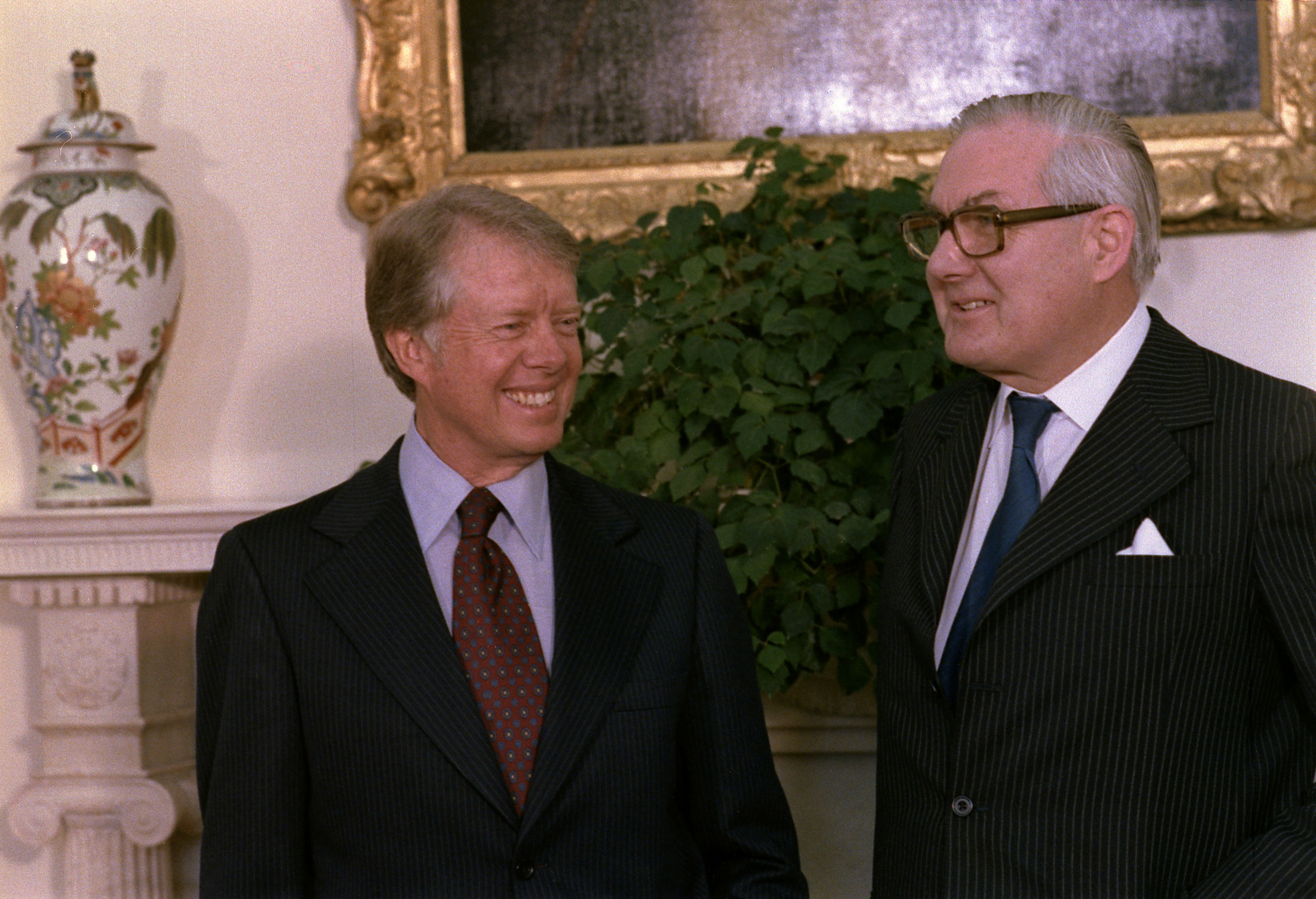

When Harold Wilson returned as Prime Minister after Labour's victory in the February 1974 United Kingdom general election, he appointed Callaghan as Foreign Secretary in March 1974.

In July 1974, a severe crisis erupted in Cyprus following a coup d'état sponsored by the Greek junta, which installed the pro-Greek leader Nikos Sampson as President, threatening to unify the island with Greece. Immediate inter-communal violence broke out between the island's Greek and Turkish communities, prompting Turkey to launch an invasion to protect the Turkish population. Britain, involved as a signatory of the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee, dispatched troops alongside the UN to prevent further Turkish advancement. Callaghan led diplomatic efforts to secure a ceasefire and called for tripartite meetings with Britain, Greece, and Turkey. A ceasefire was called on 22 July, and by August, an agreement was reached for a permanent ceasefire, establishing a UN-patrolled buffer zone between the Greek and Turkish controlled parts of the island. As of the present, the island remains partitioned as a result of the Cyprus problem.

Labour had entered office with a commitment to renegotiate the terms of the United Kingdom's membership in the European Communities (EC), followed by a referendum on whether to remain under the revised terms. Callaghan was tasked with leading these crucial negotiations. Once the talks concluded, Callaghan led the Cabinet in declaring the new terms acceptable, and he actively supported the successful "Yes" vote campaign in the 1975 referendum, which confirmed the UK's continued membership of the EC. Although Callaghan had previously been associated with the Eurosceptic wing of the Labour Party, his involvement in these negotiations and the referendum led him to become a convert to the pro-European cause. In recognition of his contributions, he was awarded the Freedom of the City of Cardiff on 16 March 1975.

In 1975, Callaghan undertook a significant diplomatic mission to Uganda to secure the release of British lecturer Denis Hills, who had been sentenced to death by Uganda's dictator Idi Amin for writing a book critical of him. Following appeals for clemency from both the Queen and the Prime Minister, Amin agreed to release Hills on the condition that Callaghan personally appeared to escort him back to the UK.

Also in 1975, Argentina asserted territorial claims over the Falkland Islands. In response, Callaghan dispatched HMS Endurance to the islands, a clear message to Argentina that Britain would defend them. Seven years later, in 1982, Callaghan would criticise Margaret Thatcher's government for its decision to withdraw Endurance from the islands, a decision that contributed to the Argentine invasion that year. Furthermore, on 23 March 1976, shortly before becoming Prime Minister, Callaghan called on Rhodesia's Ian Smith regime to transition to black majority rule, contributing to the eventual end of white minority rule in Africa.

4. Election as Leader of the Labour Party (1976)

The circumstances surrounding James Callaghan's election as Leader of the Labour Party and his subsequent appointment as Prime Minister were unexpected, shaped by a sudden change in leadership and a strong consensus within his party.

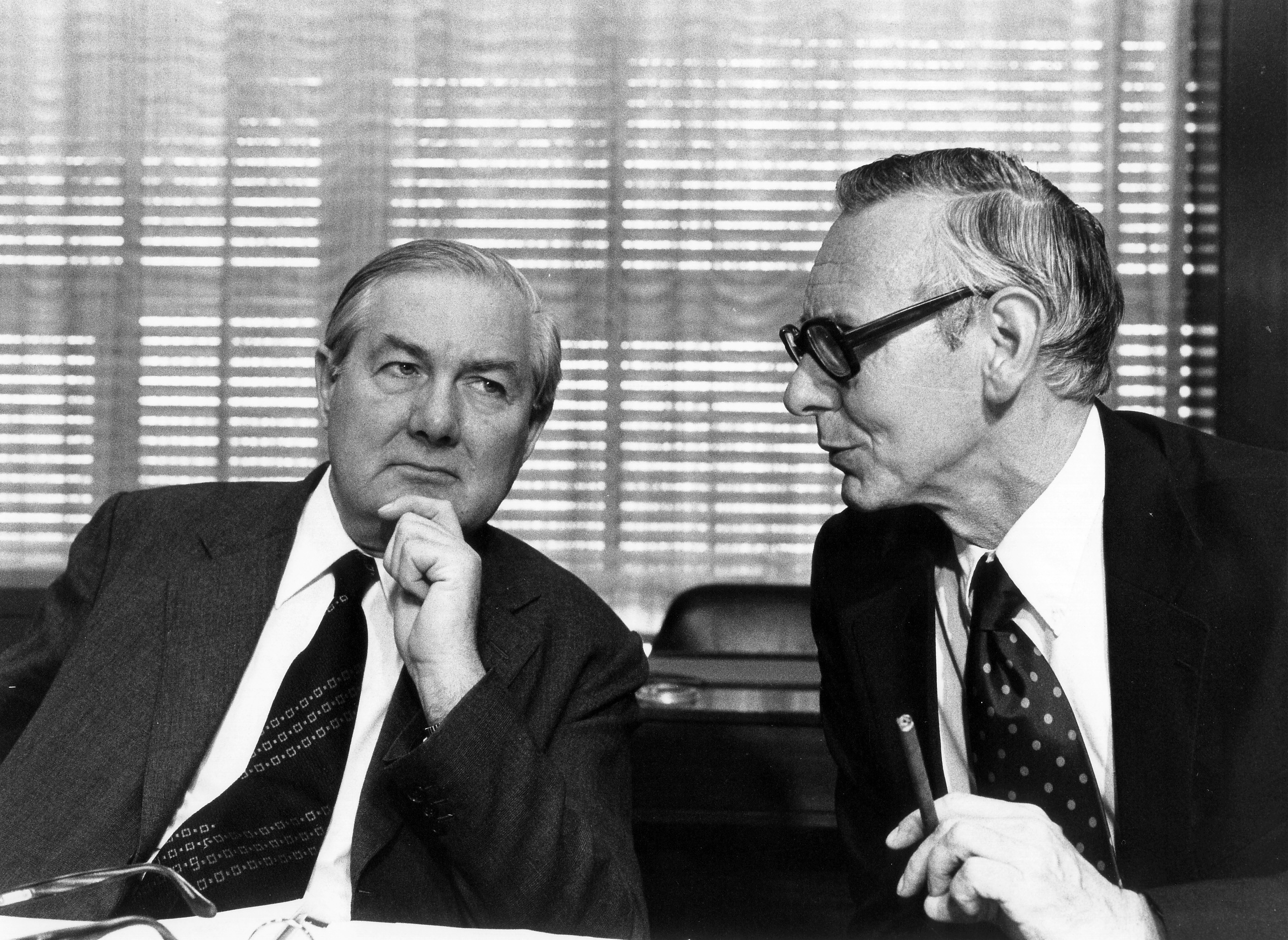

On 16 March 1976, Harold Wilson unexpectedly announced his resignation as Prime Minister. Although the news came as a surprise to most, Callaghan had been discreetly informed by Wilson several days in advance. In the ensuing 1976 Labour Party leadership election, Callaghan quickly emerged as the favourite candidate. Despite being the oldest contender at 64 years old, he was also the most experienced and, crucially, the least divisive figure within the party. His broad appeal across all factions of the Labour movement proved decisive, securing his victory through the ballot of Labour MPs. Consequently, on 5 April 1976, James Callaghan was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

5. Premiership (1976-1979)

James Callaghan's premiership was a period of significant economic and political turbulence for Britain. He was the first Prime Minister to have previously held all three other leading Cabinet positions: Chancellor of the Exchequer, Home Secretary, and Foreign Secretary. His time in office was dominated by efforts to stabilise the economy, manage a fragile minority government, and contend with widespread industrial unrest.

Upon becoming Prime Minister, Callaghan immediately undertook a Cabinet reshuffle. He appointed Anthony Crosland to his former role as Foreign Secretary, while Merlyn Rees took over as Home Secretary, replacing Roy Jenkins, whom Callaghan nominated to become President of the European Commission. Callaghan also notably removed Barbara Castle, with whom he had a difficult relationship, from the Cabinet, assigning her social security portfolio to David Ennals. He maintained Harold Wilson's policy of a balanced cabinet and heavily relied on Michael Foot, the man he had defeated for the party leadership, making him Leader of the House of Commons and tasking him with steering the government's legislative programme. Callaghan also maintained a good working relationship with Ian Macleod when Macleod was Shadow Minister in the 1960s.

5.1. Economic challenges and the IMF loan

Callaghan assumed office during a challenging period for the British economy, which was still recovering from the 1973-1975 global recession and was plagued by double-digit inflation and rising unemployment. Within months of his premiership, his government faced a severe financial crisis, known as the 1976 sterling crisis, which compelled Chancellor Denis Healey to request a substantial loan of $3.90 B USD from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to support the value of sterling.

The IMF's demand for significant public spending cuts in return for the loan caused considerable alarm among Labour's supporters. The Cabinet itself was divided on the issue, with the party's left wing, led by Tony Benn, proposing an Alternative Economic Strategy that involved protectionism as an alternative to the loan. However, this option was ultimately rejected. After intense negotiations, the government successfully secured a reduction in the proposed public spending cuts from an initial £5.00 B GBP to £1.50 B GBP in the first year, followed by £1.00 B GBP annually for the subsequent two years.

As it transpired, the loan proved to be less critical than anticipated, largely because the Treasury had overestimated the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement. The government ultimately only needed to draw on half of the allocated loan, which was fully repaid by 1979. By 1978, the economic situation showed signs of improvement, with falling unemployment and inflation declining to single digits. This recovery allowed Healey to introduce an expansionary budget in April 1978. Callaghan was widely credited for his skillful handling of the IMF crisis, managing to avoid any resignations from his Cabinet and negotiating significantly lower spending cuts than initially demanded.

5.2. Minority government and political negotiations

Callaghan's premiership was largely defined by the inherent difficulties of governing without a parliamentary majority. Although Labour had secured a narrow majority of three seats in the October 1974 United Kingdom general election, this advantage had evaporated by April 1976 due to by-election losses and the defection of two MPs to the breakaway Scottish Labour Party. This left Callaghan heading a minority government, necessitating deals with smaller parties to maintain legislative support.

In March 1977, an arrangement known as the Lib-Lab pact was negotiated with Liberal Party leader David Steel, providing the Labour government with crucial support. This pact lasted until August of the following year. Subsequently, deals were forged with various smaller parties, including the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Welsh nationalist Plaid Cymru. These arrangements prolonged the government's lifespan, but in return, the nationalist parties demanded devolution to their respective constituent countries.

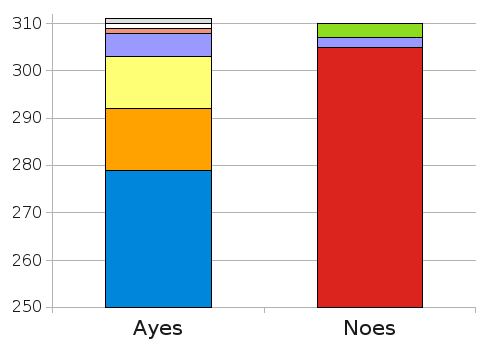

Referendums on Scottish and Welsh devolution were held in March 1979. The 1979 Welsh devolution referendum saw a large majority vote against devolution. In contrast, the 1979 Scottish devolution referendum returned a narrow majority in favour, but it failed to reach the required threshold of 40% of the entire electorate in support. When the Labour government consequently refused to proceed with establishing the proposed Scottish Assembly, the SNP withdrew its support for the government. This action ultimately triggered a vote of no confidence by the Conservatives against Callaghan's government on 28 March 1979. The motion was lost by a single vote (311-310), forcing a general election.

5.4. The Winter of Discontent

Over the summer of 1978, most opinion polls showed Labour with a lead of up to five points, and there was growing expectation that Callaghan would call an autumn election, which would have granted him a second term in office until autumn 1983. The economy had begun to show signs of improvement: 1978 was a year of economic recovery for Britain, with inflation falling to single digits, unemployment declining from a peak of 1.5 million in the third quarter of 1977 to 1.3 million a year later, and general living standards rising by more than 8%.

Famously, Callaghan kept the opposition guessing about the election timing and was widely expected to declare it in a broadcast on 7 September 1978. Instead, he announced that the election would be delayed until the following year, a decision met with widespread surprise. This decision not to call an election was subsequently seen by many as a significant political miscalculation. Callaghan himself later admitted that it was an error of judgement. His actions were interpreted by some as a sign of his dominance over the political scene, and he famously ridiculed his opponents by singing the old-time music hall star Vesta Victoria's song "Waiting at the Church" at that month's Trades Union Congress (TUC) meeting. While this gesture was celebrated by the TUC at the time, it has since been interpreted as a moment of hubris. Callaghan intended to convey that he had not promised an election, but many observers misread his message as a sign that he was unprepared for an election, which the Conservatives seized upon. Private polling conducted by the Labour Party in autumn 1978 indicated that the two main parties had similar levels of support.

Callaghan's strategy for addressing Britain's long-term economic difficulties involved a policy of wage restraint, which had been in operation for four years with reasonable success. He gambled that a fifth year of restraint would further improve the economy and enable him to be re-elected in 1979, and he therefore attempted to cap pay rises at 5% or less. However, the trade unions rejected continued wage restraint, leading to a wave of widespread industrial action and strikes during the winter of 1978-1979, a period famously known as the "Winter of Discontent." These strikes secured higher pay for workers but caused significant disruption to public services and the economy, making Callaghan's government deeply unpopular.

Callaghan's response to an interview question only exacerbated the situation. Returning to the United Kingdom from the Guadeloupe Conference in January 1979, Callaghan was asked, "What is your general approach, in view of the mounting chaos in the country at the moment?" Callaghan replied, "Well, that's a judgement that you are making. I promise you that if you look at it from outside, and perhaps you're taking rather a parochial view at the moment, I don't think that other people in the world would share the view that there is mounting chaos." This dismissive reply was famously reported in The Sun under the headline "Crisis? What Crisis?". Callaghan later acknowledged in retrospect that he had "let the country down" during this period.

During the 1979 election campaign, Callaghan privately acknowledged a fundamental shift in public sentiment, famously observing:

You know there are times, perhaps once every thirty years, when there is a sea-change in politics. It then does not matter what you say or what you do. There is a shift in what the public wants and what it approves of. I suspect there is now such a sea change and it is for Mrs Thatcher.

The 1979 defeat marked the beginning of 18 years in opposition for the Labour Party, the longest such period in its history.

5.5. 1979 general election and change of government

The "Winter of Discontent" severely impacted Labour's standing in opinion polls. Having topped most pre-winter polls by several points, by February 1979, at least one poll showed the Conservatives leading Labour by 20 points, making a Labour defeat in the forthcoming election seem inevitable. In the run-up to the election, the Daily Mirror and The Guardian supported Labour, while The Sun, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, and The Daily Telegraph supported the Conservatives.

On 28 March 1979, the House of Commons passed a motion of no confidence against his government by a single vote, 311-310, forcing Callaghan to call a general election for 3 May. The Conservatives, led by Margaret Thatcher, campaigned on the powerful slogan "Labour Isn't Working." Although Callaghan personally remained more popular with the electorate than Thatcher, the Conservatives ultimately won the election with an overall majority of 43 seats. While the Labour vote held up, with the party securing a similar number of votes to 1974, the Conservatives benefited significantly from a surge in turnout.

The 1979 defeat marked the beginning of 18 years in opposition for the Labour Party, the longest such period in its history.

6. Leader of the Opposition (1979-1980)

In the immediate aftermath of the 1979 general election defeat, James Callaghan initially wished to resign as leader of the Labour Party. However, he was persuaded to remain in the role, providing a measure of stability during a difficult period and aiming to facilitate a smooth transition for Denis Healey to be elected as his successor.

During Callaghan's 17-month tenure as Leader of the Opposition, the Labour Party was deeply fragmented by intense factional struggles between its left and right wings. These internal divisions ultimately influenced the succession. In the November 1980 leadership election, the left-wing succeeded in electing Michael Foot as Callaghan's successor, defeating Healey. Following this, Callaghan returned to the backbenches of the House of Commons.

7. Later life and retirement (1980-2005)

After stepping down from the Labour Party leadership, James Callaghan transitioned from front-line politics but remained active in public life for many years, serving as a respected elder statesman.

7.1. Departure from Parliament and entry into the House of Lords

In 1982, Callaghan co-founded the annual AEI World Forum with his friend, former U.S. President Gerald Ford. In 1983, he notably criticised Labour's proposals to reduce defence spending. In the same year, he became Father of the House, a title bestowed upon the longest continually-serving member of the Commons.

In 1987, Callaghan was appointed a Knight Companion of the Garter. He stood down at the 1987 United Kingdom general election after 42 years as an MP, having been one of the last remaining members elected in the Labour landslide of 1945. Shortly thereafter, on 5 November 1987, he was elevated to the House of Lords as a life peer with the title Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, of the City of Cardiff in the County of South Glamorgan. In 1987, his autobiography, Time and Chance, was published. He also served as a non-executive director of the Bank of Wales.

A notable contribution during his retirement involved the copyright of Peter Pan. His wife, Audrey, a former chairman (1969-1982) of Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), noticed a newspaper letter pointing out that the copyright, which had been assigned by J. M. Barrie to the hospital, was due to expire at the end of 1987. In 1988, Callaghan moved an amendment to the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, then under consideration in the House of Lords, to grant the hospital a perpetual right to royalty despite the copyright's lapse. This amendment was passed by the government.

During the 1980s, Lord Callaghan supported the work of the Jim Conway Memorial Foundation, a registered educational charity, delivering its inaugural memorial lecture in 1981 and chairing a symposium in 1990. In a humorous anecdote recorded by Tony Benn in his diary entry of 3 April 1997, a young Labour volunteer telephoned Callaghan during the 1997 general election campaign, asking if he would be willing to become more active in the party. Callaghan reportedly replied, "Well I was a Labour Prime Minister-what more could I do?"

In a revealing interview broadcast on the BBC Radio 4 programme The Human Button, Callaghan became the only Prime Minister to publicly state his opinion on ordering a nuclear retaliation in the event of an attack on the United Kingdom. He said, "If it were to become necessary or vital, it would have meant the deterrent had failed, because the value of the nuclear weapon is frankly only as a deterrent... But if we had got to that point, where it was, I felt, necessary to do it, then I would have done it. I've had terrible doubts, of course, about this. I say to you, if I had lived after having pressed that button, I could never, ever have forgiven myself." In October 1999, Callaghan told The Oldie Magazine that he would not be surprised to be considered Britain's worst Prime Minister in 200 years, acknowledging that he "must carry the can" for the "Winter of Discontent."

One of his final public appearances occurred on 29 April 2002, shortly after his 90th birthday. He attended a dinner at Buckingham Palace with Queen Elizabeth II, then-Prime Minister Tony Blair, and three other surviving former prime ministers-Edward Heath, Margaret Thatcher, and John Major. This event formed part of the celebrations for the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II, and his daughter, Margaret, Baroness Jay, who served as Leader of the House of Lords from 1998 until 2001, also attended.

7.2. Personal life and interests

Callaghan's personal interests included rugby (he played lock for Streatham RFC before the Second World War), tennis, and agriculture. He married Audrey Elizabeth Moulton in July 1938; they had met while working as Sunday School teachers at their local Baptist church. They had three children:

- Margaret, who was born on 18 November 1939 and later married Peter Jay and then Professor Michael Adler. She became Baroness Jay of Paddington and served as Leader of the House of Lords from 1998 to 2001.

- Julia, born in 1942, who married Ian Hamilton Hubbard in 1967 and settled in Lancashire.

- Michael, born in 1945, who married Jennifer Morris in 1968 and settled in Essex.

In 1968, Callaghan purchased a farm in Ringmer, East Sussex, where he and his wife engaged in full-time farming after his retirement.

There has been some discussion regarding Callaghan's religious beliefs in his adult life. While the Baptist nonconformist ethic profoundly influenced his public and private life, some sources claim he was an atheist who lost his belief in God while a trade union official. However, his son, Michael Callaghan, has disputed this, stating, "My father, Jim Callaghan, was brought up as a practising Baptist and as a young man was a Sunday school teacher. As a young man embracing socialism he had difficulties reconciling his new beliefs with the teachings of his church, but he was persuaded to stay in his Baptist chapel. [...] Incidentally, the title of his autobiography is 'Time and Chance', a quote from Ecclesiastes 9:11."

7.3. Death

James Callaghan died on 26 March 2005, at the age of 92, at his home in Ringmer, East Sussex. His cause of death was attributed to lobar pneumonia, cardiac failure, and kidney failure. He passed away just one day before his 93rd birthday and 11 days after his wife of 67 years, Audrey, who had spent her last four years in a nursing home due to Alzheimer's disease. At the time of his death, he was Britain's longest-lived former prime minister, having surpassed Harold Macmillan's record 39 days earlier. He died four months before former Prime Minister Edward Heath.

Lord Callaghan was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in a flowerbed around the base of the Peter Pan statue near the entrance of London's Great Ormond Street Hospital, where his wife had formerly chaired the board of governors. Following his death, his Order of the Garter Banner was transferred from St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle to Llandaff Cathedral in Cardiff.

8. Legacy and assessment

James Callaghan's political legacy remains a subject of ongoing historical debate, with assessments varying widely depending on political perspective and the specific period of his career under scrutiny. He is remembered as a pragmatic and experienced politician who served Britain during a period of significant economic and social upheaval.

8.1. Positive assessments

Callaghan is widely acknowledged for his unique achievement of holding all four Great Offices of State, a testament to his extensive experience and political longevity. Supporters highlight his pragmatic leadership and his efforts to maintain unity within the Labour Party, particularly in his ongoing relationship with trade unions, despite the challenges of the "social contract." His handling of the 1976 IMF crisis is often cited as a key success, where he skillfully negotiated reduced spending cuts and avoided Cabinet resignations, ultimately stabilising the economy by 1978.

His contributions as Foreign Secretary, including the renegotiation of Britain's EEC membership terms and his diplomatic efforts during the Cyprus crisis, are also viewed positively. Domestically, his government's reforms, such as the Race Relations Act 1976 and the initiation of "The Great Debate" on education, are seen as significant steps in social and educational policy. Many historians, including his biographer Kenneth O. Morgan, often offer a generally favourable assessment of the middle period of his premiership, praising his administrative efficiency and calm demeanour during crises. Bernard Donoughue, a senior official in his government, depicted Callaghan as a strong and effective administrator.

8.2. Criticisms and controversies

Callaghan's legacy is also marked by significant criticisms and controversies, particularly concerning the latter part of his premiership. From the left-wing of the Labour Party, he is sometimes seen as a "traitor" who abandoned traditional socialist commitments, particularly after his decision to seek the IMF loan in 1976, which critics argue laid the foundations for Thatcherism and the abandonment of full employment. His rigorous pursuit of a policy of controlling income growth is blamed by some for precipitating the "Winter of Discontent." Conversely, writers on the right of the Labour Party criticised him as a weak leader who was unable to stand up to the party's left wing. More recent "New Labour" writers, admiring Tony Blair, often identify Callaghan with an outdated form of partisanship that needed to be repudiated by modernisers.

Almost all commentators agree that Callaghan made a serious political miscalculation by not calling a general election in the autumn of 1978, when Labour's opinion poll ratings were more favourable. This decision is frequently cited as a moment of "hubris" that directly led to the devastating "Winter of Discontent" and the subsequent loss of the 1979 election. His infamous "Crisis? What Crisis?" response to a question about mounting chaos during the strikes became an enduring symbol of his government's perceived detachment from public suffering. Callaghan himself later admitted that not calling an election was an error of judgement and that he "must carry the can" for the "Winter of Discontent."

8.3. Enduring influence

The historical consensus on Callaghan's premiership often portrays it as a period that reinforced a sense of Labour's inability to achieve positive outcomes, particularly in controlling inflation and trade unions, or resolving issues like the Northern Ireland problem and devolution. This perspective suggests that his government's struggles ultimately contributed to Margaret Thatcher's decisive victory in 1979, ushering in a new era of Conservative dominance and a long period of opposition for the Labour Party.

Despite the criticisms, Callaghan's long career and unique experience as the only Prime Minister to have held all four Great Offices of State leave an enduring mark on British political history. His blend of pragmatic caution and deep roots in the Labour movement's trade union tradition represents a distinct phase in the party's development.