1. Early Life and Greek Royal Family

Helen's early life was shaped by her birth into the Greek royal family, her upbringing across various European nations, and the significant political instability that frequently plunged Greece into crisis and forced her family into exile.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Helen was born on May 2, 1896, in Athens, Greece. She was the third child and eldest daughter of Crown Prince Constantine of Greece and Princess Sophia of Prussia. Her paternal grandfather was King George I. From a young age, she was affectionately known by the nickname "Sitta" because her brother Alexander struggled to pronounce the English word "sister" correctly. Helen developed a particularly close bond with Alexander, who was only three years her senior. Her siblings included her two older brothers, George and Alexander, and her younger siblings, Paul, Irene, and Katherine. All three of her brothers would eventually reign as Kings of Greece.

1.2. Childhood and Education

Helen spent the majority of her childhood in Athens. During the summers, she and her family would often travel through the Hellenic Mediterranean aboard the royal yacht Amphitrite or visit her maternal grandmother, Dowager Empress Victoria, in Germany. From the age of eight, Helen began spending parts of her summers in Great Britain, particularly in the regions of Seaford and Eastbourne. She was raised in a strongly anglophile environment, surrounded by British tutors and governesses, including Miss Nichols, who took special care of her education and upbringing.

1.3. Political Upheavals in Greece

Helen's early life was marked by profound political instability in Greece. On August 28, 1909, a group of Greek officers known as the "Military League," led by Nikolaos Zorbas, organized the Goudi coup against her grandfather, King George I. Although they claimed to be monarchists, the League demanded the dismissal of the king's sons from military posts, blaming Crown Prince Constantine for Greece's defeat against the Ottoman Empire in the Thirty Days' War of 1897. The situation was so tense that George I's sons were forced to resign their military positions. The Diadochos (Crown Prince) Constantine decided to leave Greece with his family, moving to the Schloss Friedrichshof at Kronberg in Germany for several months. This marked Helen's first experience of exile at the age of 14.

After a period of tension, the political situation in Greece eventually stabilized, allowing Constantine and his family to return. In 1911, Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos reinstated Constantine to his military duties. The First Balkan War erupted a year later, enabling Greece to annex significant territories in Macedonia, Epirus, Crete, and the North Aegean. During this conflict, King George I was assassinated in Thessaloniki on March 18, 1913, and Helen's father succeeded him as King Constantine I. Following these events, Helen spent weeks touring Greece, exploring Greek Macedonia and the battlefields of the First Balkan War with her father and brother Alexander. However, this calm was short-lived as the Second Balkan War began in June 1913. Greece again emerged victorious, expanding its territory by 68% after the Treaty of Bucharest.

During World War I, King Constantine I initially sought to maintain Greece's neutrality, believing the country was not ready for another conflict after the Balkan Wars. However, due to his German education and ties to Emperor William II (his brother-in-law), Constantine I was accused of supporting the Triple Alliance and desiring the defeat of the Allies. This led to a rapid falling out with Prime Minister Venizelos, who advocated for supporting the Triple Entente to fulfill the Megali Idea. In October 1916, Venizelos, protected by the Entente powers, formed a parallel government in Thessaloniki. Central Greece was occupied by Allied forces, leading to a civil war known as the National Schism.

These tensions severely impacted Constantine I's health; he became seriously ill in 1915 with pleurisy aggravated by pneumonia, nearly dying. Rumors spread that Queen Sophia had injured him during an argument over his stance in the war. The king's health declined to the point that a ship was sent to the Island of Tinos to retrieve a miraculous icon of the Virgin and Child, which was believed to have aided his partial recovery after he kissed it. These events deeply affected Princess Helen, who was very close to her father. Impressed by his recovery, she developed a profound religiosity that remained with her throughout her life.

Despite these difficulties, Constantine I refused to change his policies, facing increasing opposition from the Triple Entente and Venizelists. On December 1, 1916, the Greek Vespers occurred, where Allied soldiers clashed with Greek reservists in Athens, and the French fleet bombarded the Royal Palace. During this attack, Helen narrowly escaped death when gunfire from the Zappeion nearly struck her as she ran to the palace gardens, only to be pulled back inside by the royal Garde du Corps.

Finally, on June 10, 1917, Charles Jonnart, the Allied High Commissioner in Greece, demanded the king's abdication. Under threat of invasion in Piraeus, Constantine I agreed to go into exile without formally abdicating. The Allies, not wishing to establish a republic, chose Prince Alexander, the younger brother of the Diadochos George, as the new king, viewing him as a more malleable ruler.

2. Marriage and Life as Crown Princess of Romania

Helen's journey into the Romanian royal family began with her marriage to Crown Prince Carol, a union that quickly led to the birth of their son Michael but was ultimately plagued by Carol's infidelity and abandonment.

2.1. Meeting Crown Prince Carol and Engagement

On June 11, 1917, the Greek royal family secretly fled their palace, surrounded by loyalists who resisted their departure. Constantine I, Queen Sophia, and five of their children left Greece from the port of Oropos, embarking on a path of exile. This was the last time Helen saw her favorite brother, Alexander, as the Venizelists, upon their return to power, prohibited any contact between King Alexander I and the rest of the royal family. After crossing the Ionian Sea and Italy, Helen and her family settled in Switzerland, primarily in St. Moritz, Zürich, and Lucerne. In exile, the family's financial situation was precarious, and Constantine I, burdened by a deep sense of failure, fell ill, contracting Spanish flu in 1918 and again nearing death. Helen and her sisters, Irene and Katherine, spent considerable time with him, trying to distract him from his worries. Helen also attempted to reconnect with Alexander I during his visit to Paris in 1919, but an officer escorting the king refused to pass along her calls or those from other family members.

In 1920, Queen Marie of Romania, Sophia's first cousin, visited the Greek exiles in Lucerne with her daughters Elisabeth, Maria, and Ileana. Queen Sophia, concerned about the future of her eldest and still single son, the Diadochos George, who had previously proposed to Princess Elisabeth, was eager for him to marry. George, now without a home, financially struggling, and politically marginalized since his exclusion from the Greek throne, reiterated his marriage proposal to Princess Elisabeth, who eventually accepted despite initial reservations. Pleased with the union, the Queen of Romania invited her future son-in-law and his sisters, Helen and Irene, to Bucharest for the public announcement of the royal engagement, scheduled for October 2.

Meanwhile, another member of the Romanian royal family arrived in Lucerne: Elisabeth's brother, Crown Prince Carol. He had just completed a trip around the world, undertaken to forget his morganatic wife, Zizi Lambrino, and their son, Carol. In 1918, during World War I, Carol had deserted the Romanian army to marry Lambrino in Odessa, a marriage that was later annulled by Romanian courts, forcing Carol to abandon his wife and resume his duties as heir.

In Romania, George, Helen, and Irene were received with great pomp by the royal family. Housed at Pelișor Castle, they were central to the celebrations for Crown Prince Carol's return (October 10) and the announcement of Elisabeth's engagement to the Diadochos (October 12). However, their stay was cut short. On October 24, a telegram arrived announcing the death of the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Queen Marie's mother, in Zurich. The very next day, another message informed the Greek princes that Alexander I had suddenly died in Athens after a monkey bite.

Under these circumstances, the three Greek princes and Queen Marie of Romania decided to return to Switzerland immediately. Moved by the situation and likely encouraged by his mother, Crown Prince Carol decided at the last moment to travel with them. Despite having been cold and distant towards Helen during her stay in Romania, Carol suddenly became very attentive to the princess. During the train journey, they confided in each other. Carol shared details of his affair with Zizi Lambrino, and Helen spoke of her life, her profound grief over Alexander's death, and her reluctance to return to Greece without her beloved brother. This emotional exchange led Helen to fall in love with the heir to the Romanian throne.

2.2. Marriage and Early Family Life

Soon after their arrival in Switzerland, Crown Prince Carol proposed marriage to Helen, much to the delight of the Queen of Romania, but less so to Helen's parents. Helen was determined to accept. King Constantine I assented to the engagement, but only after Carol's marriage to Zizi Lambrino was officially dissolved. Queen Sophia, however, was far less enthusiastic, lacking confidence in the Romanian crown prince and attempting to persuade Helen to reject the proposal. Despite her mother's doubts, Helen insisted, and the engagement was announced in Zürich in November 1920.

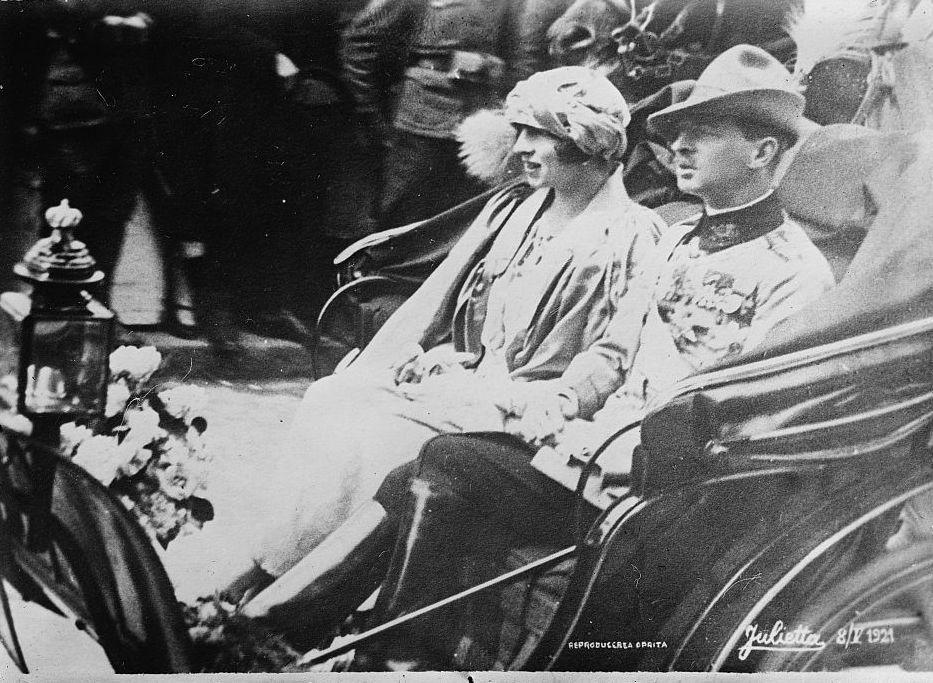

Meanwhile, in Greece, the Venizelists lost the election on November 14, 1920, in favor of Constantine I's supporters. To resolve the dynastic question, the new cabinet organized a referendum on December 5, whose disputed results indicated that 99% of the population demanded the sovereign's restoration. Under these conditions, the royal family returned to Athens, with Helen accompanied by her fiancé. For two months, they traveled through Greece, exploring its ancient ruins. They then went to Bucharest for the wedding of Diadochos George with Elisabeth of Romania on February 27, 1921, before returning to Athens for their own wedding at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens on March 10, 1921. Helen was the first Greek princess to marry in Athens, wearing the Romanian 'Greek Key' tiara, a gift from her mother-in-law. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon in Tatoi for two months before returning to Romania on May 8, 1921.

Upon her return to Romania, Helen was already pregnant. She initially stayed with Carol at the Cotroceni Palace, finding the court's pomp and protocol both impressive and tedious. The couple then moved to Foișor, an elegant Swiss-style chalet near Peleș Castle in Sinaia. It was there that Helen gave birth to her only child, Prince Michael, on October 25, 1921, just seven and a half months after her wedding. Michael was named in honor of Michael the Brave, the first unifier of the Danubian Principalities. The childbirth was difficult and required surgery, significantly weakening Helen, and doctors advised against a second pregnancy. Though the court announced Michael was premature, he weighed 9 lb (9 lb), leading to speculation that Helen was pregnant before marriage.

After Helen recovered, the couple moved to a large villa on Șoseaua Kiseleff in Bucharest in December 1921. Despite their differing interests, Carol and Helen managed to lead a seemingly bourgeois and happy life for a time. Carol engaged in reading and stamp collecting, while Helen enjoyed horseback riding and decorating their residences. The Crown Princess actively participated in social work, founding a nursing school in the capital. She was also appointed an Honorary Colonel of the 9th Cavalry Regiment, the Roșiori.

2.3. Marital Problems and Carol's Abandonment

Meanwhile, the political situation in Greece deteriorated. The Hellenic Kingdom endured a period of unrest during the Greco-Turkish War, and by 1919, King Constantine I's health was declining. Concerned for her father, Helen sought her husband's permission to return to Greece. The couple and their child left for Athens in late January 1922. While Carol departed Greece in February to attend the betrothal of his sister Maria to King Alexander I of Yugoslavia, Helen remained with her parents until April, returning to Romania with her sister Irene. By this time, the Crown Prince had resumed his affair with his former mistress, the actress Mirella Marcovici.

In June 1922, Carol and Helen traveled to Belgrade with the entire Romanian royal family for the wedding of Alexander I and Maria. Back in Bucharest, the Crown Princess resumed her role as the heir's wife, participating in official acts and supporting the sovereign during ceremonies. Like many women of her rank, Helen engaged in social works. However, she remained anxious about her family, visiting her sister Irene, her aunt Maria, and her Greek cousins in a futile attempt to console herself about her parents' distance.

In September 1922, a military coup forced King Constantine I to abdicate in favor of his son George II and go into exile. Without real power and dominated by revolutionaries, George II was himself forced to abdicate after only fifteen months, following a failed pro-royalist coup in October 1923. Devastated by these events, Helen immediately went to Italy to be with her parents in exile. Shortly after the coronation of King Ferdinand I and Queen Marie of Romania in Alba Iulia on October 15, 1922, Helen left for Palermo, where she remained until her father's death on January 11, 1923.

Bored by his wife's absence, Carol eventually invited his mother-in-law to stay in Bucharest. However, the dowager queen arrived with no fewer than 15 Greek princes and princesses, unannounced, to his home. Increasingly irritated by the invasive presence of his wife's family, Carol was also hurt by Helen's refusal to fulfill her marital duties. Jealous, the Crown Prince suspected Helen of having an affair with the charming Prince Amedeo of Savoy, Duke of Aosta, a frequent guest of the Greek royal couple in Sicily. These circumstances led to Helen and Carol's separation, though the Crown Princess maintained appearances by dedicating more time to the education of her son, Prince Michael.

In the summer of 1924, Carol met Elena Lupescu, better known as Magda Lupescu, with whom he began an affair around February 14, 1925. While Carol had other extramarital relationships since his marriage, this one developed into a serious bond, alarming not only Helen (who had previously been conciliatory towards his infidelities) but also the rest of the Romanian royal family, who feared Lupescu could become another Zizi Lambrino. In November 1925, Carol was sent to the United Kingdom to represent the royal family at the funeral of Dowager Queen Alexandra. Despite promises to his father, King Ferdinand I, he used the trip to openly live with his mistress. Refusing to return to Bucharest, Carol officially renounced the throne and his prerogatives as Crown Prince on December 28, 1925.

In Romania, Helen was distraught by Carol's actions, especially as Queen Marie partly blamed her for the failure of her marriage. The Crown Princess wrote to her husband, urging him to return. She also tried to convince politicians to delay Carol's exclusion from the royal succession and proposed traveling to meet him. However, Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu, who disliked the Crown Prince due to his sympathy for the National Peasants' Party, categorically opposed this. Brătianu even accelerated the exclusion procedures by convening both Houses of the Parliament to register the act of renunciation and appoint young Prince Michael as the new heir to the throne.

2.4. Divorce and Carol's Renunciation

On January 4, 1926, the Romanian Parliament ratified Carol's renunciation, and a royal ordinance was issued granting Helen the title of Princess of Romania. Additionally, she was included in the Civil list, a privilege previously reserved for the sovereign and the heir. After King Ferdinand I was diagnosed with cancer, a Regency Council was formed during Michael's minority, with Prince Nicholas as its head, assisted by Patriarch Miron and magistrate Gheorghe Buzdugan (replaced by Constantine Sărățeanu after his death in 1929). Despite these changes, Helen continued to hope for her husband's return and stubbornly refused his divorce requests from abroad.

In June 1926, shortly before her father-in-law's death, Helen traveled to Italy for the funeral of her paternal grandmother, Dowager Queen Olga of Greece, and moved with her mother to the Villa Bobolina in Fiesole. The princess attempted to arrange a meeting with Carol during her stay, but he canceled at the last minute after initially agreeing.

3. Carol II's Reign and Helen's Exile

Following Carol II's controversial return and assumption of the throne, Helen was forced into exile, enduring severe restrictions on her contact with her son, Michael.

3.1. Michael I's Accession and Regency

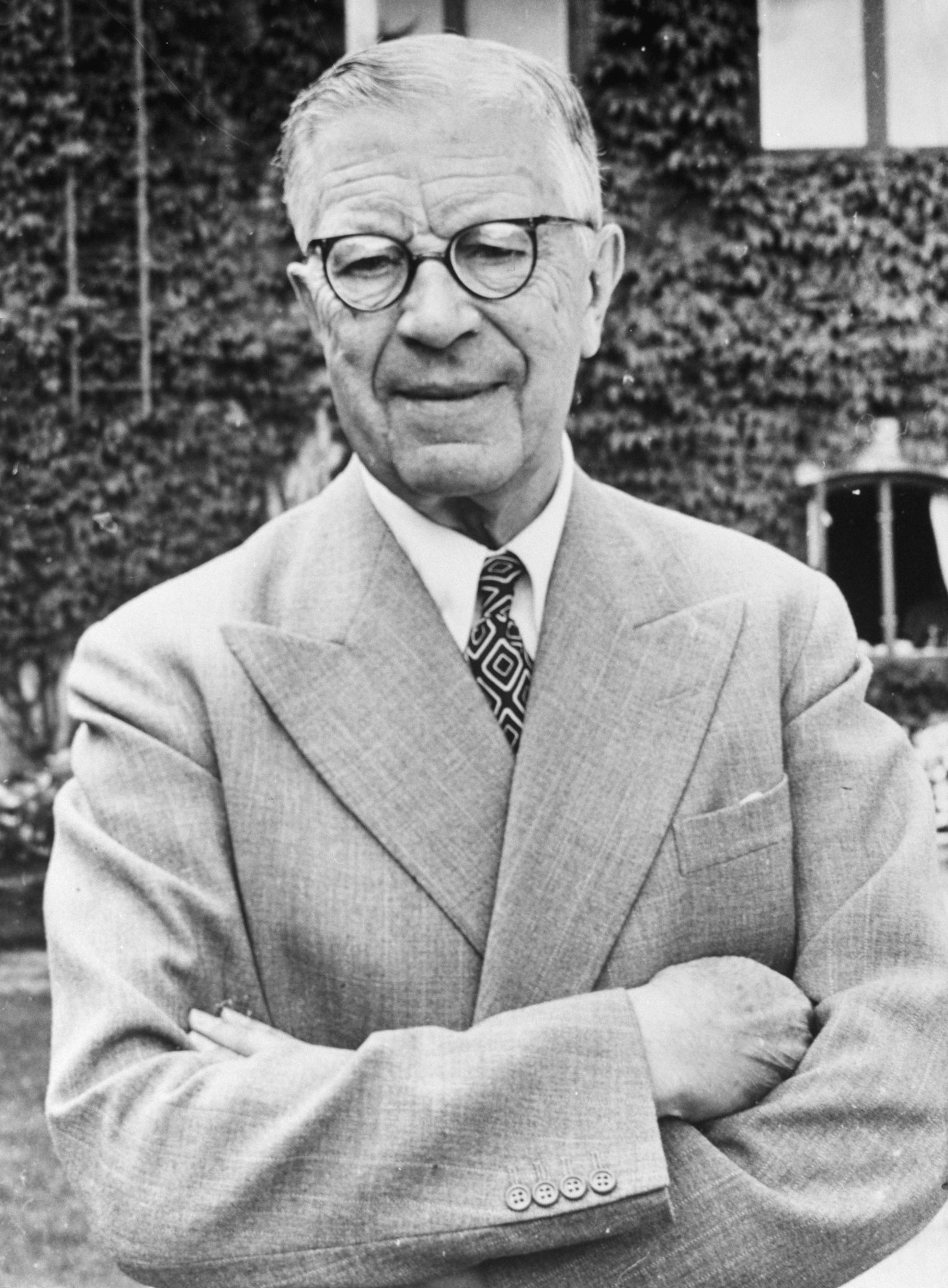

In the spring of 1927, Queen Marie made an official visit to the United States. During her absence, Helen and her sister-in-law Elisabeth cared for King Ferdinand I, whose health rapidly declined. The king died on July 20, 1927, at Peleș Castle, and his five-year-old grandson succeeded him as Michael I, with the Regency Council assuming control of the country. However, Carol retained many supporters in Romania, known as "Carlists," and the National Liberal Party began to fear his return.

After initially trying to persuade Carol to return to Bucharest, Helen gradually changed her stance. Anxious to protect her son's rights and likely influenced by Prime Minister Barbu Știrbey, she requested a divorce, which she easily obtained. On June 21, 1928, the marriage was dissolved by the Romanian Supreme Court on grounds of incompatibility. Helen also distanced herself from her mother-in-law, Queen Marie, who complained of being separated from the young king and openly criticized Helen's Greek entourage. In these circumstances, the dowager queen began to align herself with her eldest son and the Carlist movement.

3.2. Carol II's Return to the Throne

As the Regency Council struggled to govern the country, Carol increasingly appeared as a potential savior who could resolve Romania's problems. However, his supporters, including Prime Minister Iuliu Maniu, leader of the National Peasants' Party, continued to demand his separation from Magda Lupescu and reconciliation with Helen, which he refused. Thanks to his numerous supporters, Carol finally orchestrated his return to Bucharest on the night of June 6-7, 1930. He was joyfully welcomed by the population and political class, then proclaimed himself king under the name of Carol II.

3.3. Forced Exile and Limited Contact with Michael

Upon his return to power, Carol II initially refused to see Helen, though he expressed a desire to meet his son, who had been demoted to the rank of heir-apparent with the title of Grand Voivod of Alba Iulia by the Romanian Parliament on June 8, 1930. To reunite with Michael, the king eventually agreed to meet his former wife. Accompanied by his brother Nicholas and sister Elisabeth, he visited Helen at her villa on Șoseaua Kiseleff. Helen greeted him coldly but, for their son's sake, offered her friendship.

In the following weeks, Helen faced combined pressures from politicians and the Romanian Orthodox Church, who urged her to resume her conjugal life with Carol II and accept being crowned alongside him at a ceremony in Alba Iulia, scheduled for September 21, 1930. Despite her reluctance, the princess agreed to a reconciliation and reconsidered the annulment of her divorce, but on the condition of having a separate residence. Under these terms, the former spouses lived separately, with Carol II occasionally joining Helen for lunch, and Helen sometimes having tea with him at the royal palace. In July, the king, his former wife, and son traveled together to Sinaia. While Carol II stayed at Foișor, Helen and Michael resided at Peleș Castle. The family gathered daily for tea, and on July 20, Carol II and Helen made a public appearance together at a ceremony commemorating King Ferdinand I.

In August 1930, the government presented a decree to Carol II for his signature, officially confirming Helen as Her Majesty, the Queen of Romania. However, the king crossed this out, declaring Helen to be Her Majesty Helen (i.e., with the style Majesty, but not the title Queen). Helen refused to allow anyone to use this style in her presence. Due to these circumstances, the proposed coronation of the two former spouses was postponed. The return of Magda Lupescu to Romania ultimately ended any reconciliation efforts. Soon, the king managed to have Michael moved to his side, and Helen was allowed to see her son daily in exchange for her political silence. Increasingly isolated, the princess was forced into exile by her former husband, consenting to a separation agreement in October 1931. In exchange for her silence, and through the mediation of her brother, the former King George II of Greece, and her sister-in-law Elisabeth, Helen received substantial monetary compensation. With Carol II's approval, she gained the right to stay four months a year in Romania and to receive her son abroad for two months annually. She retained her residence in Bucharest, with the king funding its maintenance during her absence. Crucially, Helen received 30.00 M ROL to purchase a home abroad and an annual pension of 7.00 M ROL.

3.4. Life in Italy

In November 1931, Helen left Romania for Germany to be with her mother, Dowager Queen Sophia of Greece, who was seriously ill with cancer. After Sophia's death on January 13, 1932, Helen purchased her mother's house in Fiesole, Tuscany, which she made her main residence. She renamed this large house Villa Sparta, where she frequently hosted her sisters Irene and Katherine, and her brother Paul, who stayed with her for long periods.

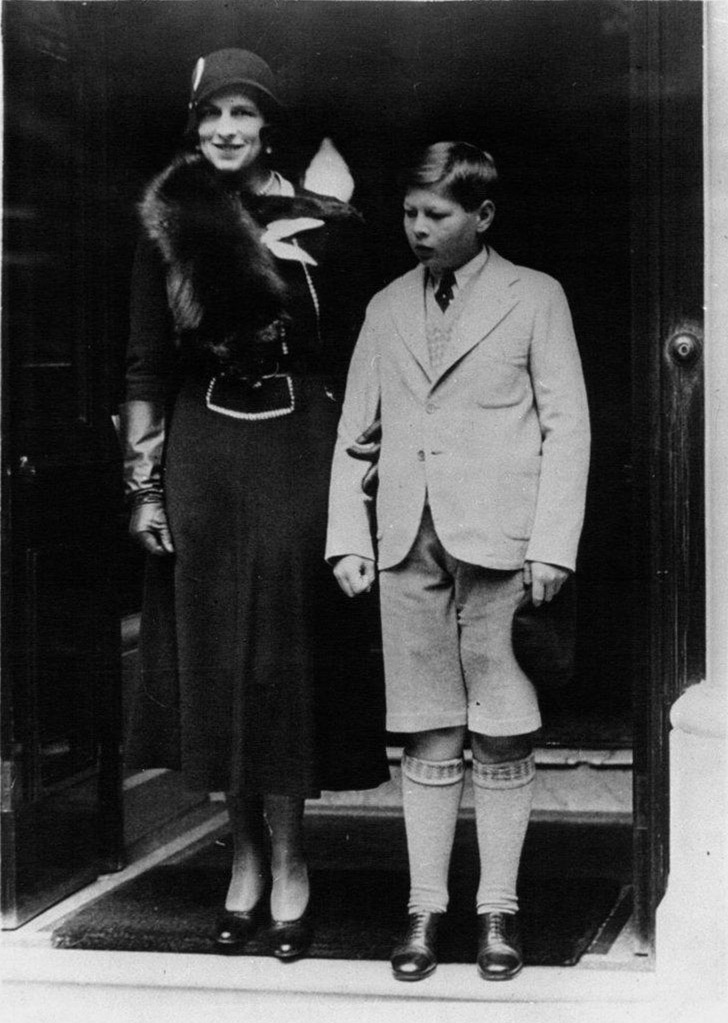

Despite the distance, friction between Helen and Carol II persisted. In September 1932, a visit by Michael and his mother to the United Kingdom became an opportunity for a new, very public conflict that made international headlines, just as Helen intended. The king demanded that the Crown Prince not wear shorts in public and not be photographed with his mother. Helen was incensed by the second stipulation and deliberately defied the first, ensuring her son was dressed in shorts and posing for an extended photo opportunity with him. After seeing the photographs of the Crown Prince in shorts published in newspapers, the king demanded Michael's return to Bucharest. Helen then granted an interview to the Daily Mail, stating her hope that "public opinion would help to preserve her parental rights." This led to a violent press campaign that enraged the king. Despite these events, Helen chose to return to Romania for Michael's birthday and threatened to go to the International Court of Justice if Carol II did not allow her to see their son.

Back in Bucharest, the princess unsuccessfully tried to involve the government in a case against the king. She then turned to her sister-in-law, the former Queen of the Hellenes, Elisabeth. However, Elisabeth was deeply shocked by the Daily Mail interview, and the two women had a violent fight during their reunion, during which Elisabeth slapped Helen. Carol II now considered his former wife a political opponent and, to undermine her prestige, initiated a press campaign against her, falsely claiming she had attempted suicide twice. After only a month in the country, Carol II imposed a new separation agreement on November 1, 1932, under which Helen was denied the right to return to Romania. The next day, she was finally forced into permanent exile in Italy. In the following years, she had no contact with her former husband, who only briefly informed her by telephone of Queen Marie's death in 1938. Despite the tensions, Prince Michael was able to see his mother every year in Florence for two months.

In Fiesole, Helen and her sisters led a relatively secluded life, though they frequently received visits from the Italian House of Savoy, which had always been welcoming to the Greek royal family during their exile. The Greek princesses also used their connections to find a wife for Diadochos Paul, who remained single. In 1935, they took advantage of Princess Frederica of Hanover's presence in Florence to arrange an encounter between her and their brother. Their efforts were successful, and Frederica quickly fell in love with Paul. However, Frederica's parents were reluctant to approve the relationship, as Paul was sixteen years older than Frederica, and her mother, Princess Victoria Louise of Prussia, was a cousin of the Diadochos. It was not until 1937 that Paul and Frederica were finally allowed to get engaged. In the meantime, the Greek monarchy was restored, and George II once again became King of Greece, but his wife Elisabeth, who filed for divorce on July 6, 1935, remained in Romania.

4. Queen Mother of Romania

Helen's return to Romania as Queen Mother coincided with the tumultuous years of World War II, during which she undertook significant humanitarian efforts, particularly to protect Jewish communities, before the monarchy was ultimately abolished by the imposition of a communist regime.

4.1. Return to Romania and World War II

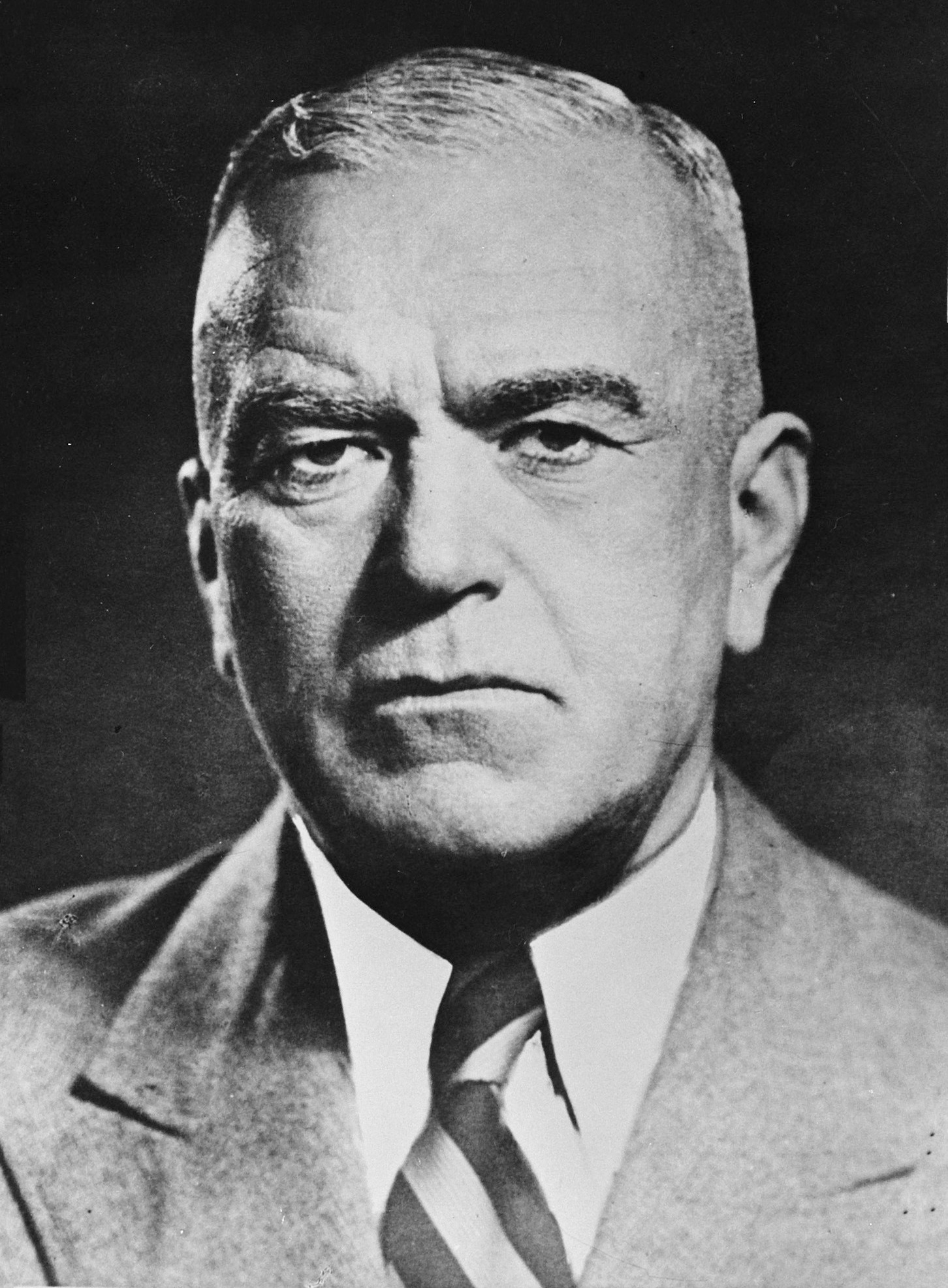

In Tuscany, Helen found a semblance of stability, despite her son's absence for most of the year. However, the outbreak of World War II once again disrupted her routine. In accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union forced Romania to cede Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina on June 26, 1940. Weeks later, Romania was also compelled to surrender Northern Transylvania to Hungary (via the Second Vienna Award on August 30, 1940) and Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria (via the Treaty of Craiova on September 7, 1940). These territorial losses marked the end of Greater Romania, which had been established after World War I. Unable to maintain his country's territorial integrity and under pressure from the Iron Guard, a fascist party supported by Nazi Germany, Carol II became increasingly unpopular and was finally forced to abdicate on September 6, 1940. His son Michael, then 18 years old, became king, while General Ion Antonescu established a dictatorship with the support of the Iron Guard.

Eager to gain favor with the new sovereign and legitimize his dictatorship, Antonescu granted Helen the title of "Queen Mother of Romania" (Regina-mamă Elena) with the style "Her Majesty" on September 8, 1940. He sent diplomat Raoul Bossy to Fiesole on September 12, 1940, to persuade her to return to Bucharest. Helen returned to Romania on September 14, 1940, but found herself subject to the dictator's whims, as he was determined to keep the royal family in a purely ceremonial role. In the years that followed, Antonescu systematically excluded the king and his mother from political responsibility and did not even inform them of his decision to declare war on the Soviet Union in June 1941.

In this difficult context, Michael I was at times prone to bouts of depression, and Helen focused her efforts on making him more active. Aware of his shortcomings, the queen mother enlisted right-wing historians to train her son in his role as sovereign. She also guided the king in his discussions and encouraged him to oppose Antonescu when she believed his policies endangered the crown.

4.2. Humanitarian Efforts and Rescue of Jews

Helen's most significant legacy lies in her courageous humanitarian efforts during World War II. Alerted by Rabbi Alexandru Șafran about the anti-Jewish persecutions, Helen personally appealed to the German ambassador Manfred Freiherr von Killinger and Antonescu to convince them to halt the deportations, supported in her efforts by Patriarch Nicodim. For his part, King Michael vigorously protested to the Conducător (leader) during the 1941 Odessa massacre and notably secured the release of Wilhelm Filderman, president of the Romanian Jewish community.

Despite these attempts at intervention, Helen and her son spent most of the conflict hosting German officers passing through Bucharest. The queen mother even met Hitler twice: first informally with her sister Irene (who was then part of the Italian Royal Family after marrying Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta in 1939), to discuss the fate of Greece and Romania within the "new Europe" in December 1940. Her second meeting was formal, with Michael I, during a trip to Italy in the winter of 1941. Above all, Helen and her son had no choice but to officially support Antonescu's dictatorship. Thus, it was Michael I who bestowed the title of Marshal upon the Conducător on August 21, 1941, after the reconquest of Bessarabia by the Romanian Army.

In the fall of 1942, Helen played a pivotal role in preventing Antonescu from carrying out his plans to deport all Jews from the Regat (Old Kingdom of Romania) to the German death camp of Bełżec in Poland. According to SS Hauptsturmführer Gustav Richter, the counselor for Jewish Affairs at the German legation in Bucharest, in a report sent to Berlin on October 30, 1942, Helen told the King that "what was happening...was a disgrace and that she could not bear it any longer, all the more so because [their names] would be permanently associated...with the crimes committed against the Jews, while she would be known as the mother of 'Michael the Wicked'." She reportedly warned the king that if the deportations were not immediately halted, she would leave the country. As a result, the King telephoned Prime Minister Ion Antonescu, leading to a meeting of the Council of Ministers and a halt to the deportations. Her moral courage and direct intervention are credited with saving thousands of Romanian Jews between 1941 and 1944.

4.3. Michael I's Coup and End of the War

From 1941, the Romanian army's participation in the invasion of the Soviet Union further strained relations between Antonescu and the royal family, who disapproved of the conquests of Odessa and Ukraine. However, it was the Battle of Stalingrad (August 23, 1942 - February 2, 1943) and the heavy losses incurred by the Romanian side that finally compelled Michael I to organize a resistance against the Conducător's dictatorship. During an official speech on January 1, 1943, the sovereign publicly condemned Romania's participation in the war against the Soviet Union, provoking the wrath of both Antonescu and Nazi Germany, who accused Helen of instigating the royal initiative. In retaliation, Antonescu tightened his control over Michael I and his mother, threatening the royal family with the abolition of the monarchy if any further provocation occurred.

Over the next few months, the suspicious death of Tsar Boris III of Bulgaria (August 28, 1943) and the successive arrests of princesses Mafalda of Savoy (September 23, 1943), who later died in Buchenwald concentration camp, and Irene of Greece (October 1943) after the overthrow of Mussolini by King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy (July 25, 1943), demonstrated to Michael I and his mother the dangers of opposing the Axis powers. The return of the Soviets to Bessarabia and the American bombing of Bucharest forced the king, despite everything, to break with Antonescu's regime. On August 23, 1944, Michael I organized a coup d'état against the Conducător, who was imprisoned and later executed. In the process, the king and his new government declared war on the Axis powers and ordered Romanian forces not to resist the Red Army, which nevertheless continued its invasion into the country.

In retaliation for this betrayal, the Luftflotte bombed Bucharest, largely destroying Casa Nouă, the main residence of the sovereign and his mother since 1940, on August 24, 1944. Nevertheless, Romanian forces gradually managed to push the Germans out of the country and also attacked Hungary to liberate Transylvania (during the Siege of Budapest, December 29, 1944 - February 13, 1945). However, the Allies did not immediately recognize Romania's reversal, and the Soviets entered the capital on August 31, 1944. An armistice was finally signed with Moscow on September 12, 1944, forcing the kingdom to accept the Soviet occupation. A climate of uncertainty swept the country as the Red Army increased its demands.

Visiting Sinaia at the time of the royal coup d'état, Helen reunited with her son the next day in Craiova. Returning to Bucharest on September 10, 1944, the king and his mother moved into the residence of Princess Elisabeth, whose relations with Helen remained tense despite their reconciliation in 1940. With increased instability in Romania, the queen mother was extremely concerned about her son's safety, fearing he could be killed, like Prince-Regent Kiril of Bulgaria, who was shot by the Communists on February 1, 1945. The queen mother also disapproved of Ioan Stârcea's influence over the sovereign and, based on information from a palace servant, accused him of espionage on behalf of Antonescu. She was also concerned about the machinations of Carol II, who apparently awaited the war's end to return to Romania, and anxiously observed the political crisis that prevented King George II from regaining power in Greece. In this difficult context, Helen had the joy of learning that her sister Irene and her young nephew Amedeo were alive, though still in German hands.

Despite these political and personal concerns, the queen mother continued her charitable activities. She provided support to Romanian hospitals and managed to save some equipment from Red Army requisitions. On November 6, 1944, she inaugurated a soup kitchen in the ballroom of the Royal Palace, which served over 11,000 meals to children in the capital over the next three months. Finally, despite Moscow's opposition, the queen mother sent aid to Moldavia, where a terrible typhus epidemic was raging.

4.4. Imposition of Communist Regime and Abolition of Monarchy

With the Soviet occupation, the membership of the Romanian Communist Party, which had only a few thousand members during Michael I's coup, exploded, and demonstrations against Constantin Sănătescu's government multiplied. Simultaneously, acts of sabotage occurred throughout the country, hindering Romania's economic recovery. Faced with the combined pressures of Soviet representative Andrey Vyshinsky and the People's Democratic Front (an offshoot of the Communist Party), the king needed to form a new government and named Nicolae Rădescu as the new Prime Minister on December 7, 1944. Nevertheless, the situation remained tense. When the new head of government called for municipal elections on March 15, 1945, the Soviet Union resumed its destabilizing operations to impose a government of its liking. The refusal of the United States and United Kingdom to intervene on his behalf led the sovereign to consider abdication, but he abandoned the idea on the advice of representatives from the two major democratic political forces, Dinu Brătianu and Iuliu Maniu. On March 6, 1945, Michael I finally appointed Petru Groza, leader of the Ploughmen's Front, as the new head of a government that included no representatives from either the Peasants or the Liberal parties.

Satisfied with this appointment, the Soviet authorities became more conciliatory towards Romania. On March 13, 1945, Moscow transferred the administration of Transylvania to Bucharest. A few months later, on July 19, 1945, Michael I was decorated with the Order of Victory, one of the most prestigious Soviet military orders. Still, the Sovietization of the kingdom accelerated. The purge of "fascist" personalities continued, and censorship was strengthened. A land reform was also implemented, causing a drop in production that ruined agricultural exports. The king, however, managed to temporarily prevent the establishment of People's Tribunals and the restoration of the death penalty.

After the Potsdam Conference and the Allies' reaffirmation of the need to establish democratically elected governments in Europe, Michael I demanded Petru Groza's resignation, which he refused. Faced with this insubordination, the sovereign began a "royal strike" on August 23, 1945, during which he refused to countersign government acts. With his mother, he locked himself in the Elisabeta Palace for six weeks before departing to Sinaia. The monarch's resistance, however, was not supported by the West, who, after the Moscow Conference of December 25, 1945, asked Romania to allow two opposition figures into the government. Disappointed by the lack of courage from London and Washington, the sovereign was shocked by the attitudes of Princesses Elisabeth and Ileana, who openly supported the communist authorities. Disgusted by these betrayals, Helen, in turn, discouraged meetings with Soviet officials and worried daily for her son's life.

The year 1946 was marked by the strengthening of the Communist dictatorship, despite the sovereign's active resistance. After several months of waiting, the parliamentary elections were held on November 19, 1946, and were officially won by the Ploughmen's Front. After that date, the situation of the king and his mother became more precarious. In their palace, they had no access to running water for three hours a day, and electricity was off for most of the day. This did not prevent Helen from maintaining her charitable activities and continuing to send food and clothing to Moldavia. In early 1947, the queen mother also obtained permission to travel abroad to visit her family. She reunited with her sister Irene, weakened after her deportation to Austria, attended the funeral of her elder brother, King George II, and participated in the marriage of her youngest sister, Princess Katherine, with British Major Richard Brandram.

The signing of the Paris Peace Treaties on February 10, 1947, marked a new stage in the sidelining of the royal family by the Communist regime. Deprived of any official duties, the king found himself even more isolated than during the "royal strike." Under these conditions, the queen mother considered exile with more determination, but she was concerned that they possessed no foreign resources, as her son refused to save money outside of Romania. As guests to the marriage of Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom with Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark (Helen's first cousin) on November 20, 1947, Michael I and his mother had an opportunity to travel together abroad. During this stay, the king fell in love with Princess Anne of Bourbon-Parma, with whom he became engaged, much to Helen's delight. This trip was also an opportunity for the queen mother to place two small paintings by El Greco from the royal collections in a Swiss bank.

5. Exile and Later Years

After the abolition of the monarchy, Helen's life was defined by continued exile, family milestones such as her son's marriage, her personal interests, and persistent financial struggles until her death in Switzerland.

5.1. Life in Exile

Despite the advice of their relatives, who urged them not to return to Romania to escape the communists, the king and his mother returned to Bucharest on December 21, 1947. They were coldly greeted by the government, which secretly hoped they would remain abroad to abolish the monarchy. When their plan failed, Prime Minister Petru Groza and General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej decided to compel the sovereign to abdicate. On December 30, 1947, they requested an audience with the king, who received them along with his mother. The two politicians demanded that Michael I sign a declaration of abdication. The king refused, stating that the Romanian population must be consulted for such a matter. The two men then threatened that if he persisted, over 1,000 students who had been arrested would be executed in retaliation. Thousands of people, including many students, had been arrested in November 1946 after clashes with Communist forces. The pro-democracy and freedom population had resisted the Communist forces sent to suppress protests by the Communist government, but in return, many protesters were arrested by Communist authorities with the help of the Red Army, following the Communist Party's falsification of the 1946 Parliament election votes, which the National Peasant's Party (PNȚ) had won with over 70%. Faced with this blackmail, Michael I renounced the crown. Only hours after the announcement, the Romanian People's Republic was proclaimed. Michael I and Helen left Romania with some partisans on January 3, 1948. Despite their close links with the Communists, Princesses Elisabeth and Ileana were also forced to leave the country a few days later, on January 12.

In exile, Michael I and Helen settled for some time in Switzerland, where the deposed sovereign bitterly observed the Western acceptance of the establishment of a communist republic in Romania. For her part, Helen was mostly concerned with their finances, as the Communists allowed them to leave with almost nothing. Despite their promises, the new Romanian authorities nationalized the properties of the former royal family on February 20, 1948, and deprived the former monarch and his relatives of their nationality on May 17, 1948. At the same time, the king and his mother had to deal with the intrigues of Carol II, who still considered himself the only legitimate sovereign of Romania and accused his ex-wife of keeping him away from their son. To achieve his ends, Carol II did not hesitate to involve Frederick, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (Head of the dynasty) and Prince Nicholas of Romania in his schemes. These concerns did not prevent Michael I and his mother from undertaking several political trips to the United Kingdom, France, and the United States to meet with government leaders and representatives of the Romanian diaspora.

5.2. Marriage of Michael I

Another source of concern for Michael I and his mother during their first months of exile was his marriage to Princess Anne of Bourbon-Parma. To discredit the former monarch, the Romanian authorities spread rumors that Michael I had given up his dynastic rights to marry the woman he loved, just as his father had done in 1925.

Adding to these difficulties, the most serious challenges were related to religion. As a Roman Catholic, Princess Anne needed to obtain a papal dispensation to marry an Orthodox. However, the Vatican was extremely reluctant to grant consent because, for dynastic reasons, the couple's children would have to be raised in Michael I's religion. After Prince René of Bourbon-Parma, Anne's father, failed in his negotiations with the Vatican, Helen decided to go to Rome with Princess Margaret of Denmark (Anne's mother) to meet Pope Pius XII. However, the meeting ended poorly, and the Pope refused to agree to the marriage. Under these circumstances, Princess Anne had no choice but to override the pontifical will and abandon a Catholic marriage. In doing so, she incurred the wrath of her uncle, Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma, who forbade members of his family from attending the royal wedding under threat of exclusion from the House of Bourbon-Parma. Once again, the queen mother tried to mediate, this time with Anne's family, but without success.

Helen had better luck with her own family. Her brother, King Paul I of Greece, offered to organize Michael's wedding in Athens, despite official protests from the Romanian government. The wedding was finally celebrated in the Greek capital on June 10, 1948, with Archbishop Damaskinos himself officiating the ceremony. Celebrated in the throne room of the Royal Palace, the wedding brought together most members of the Greek dynasty but no representatives from the Houses of Bourbon-Parma or Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. In fact, Carol II was not invited to the wedding, despite Helen having written to him about the marriage.

5.3. Return to Villa Sparta and Personal Interests

After the marriage of Michael I and Anne, Helen returned to Villa Sparta in Fiesole. Through 1951, she hosted her son and his family, who visited her at least twice a year. Over the years, the former king's family grew with the successive births of princesses Margareta (1949), Elena (1950), Irina (1953), Sophie (1957), and Maria (1964). From 1949 to 1950, Helen also housed her sister Irene and her nephew Amedeo, who later settled in a neighboring residence. Over the years, the two Greek princesses maintained a strong bond, which lasted until the death of the Duchess of Aosta in 1974. Throughout her life, Helen also remained deeply attached to Amedeo and his first wife, Princess Claude of Orléans.

Helen also made many trips abroad to visit her relatives. She traveled regularly to the United Kingdom to see her granddaughters, who were schooling there. Despite her sometimes stormy relationship with her sister-in-law, Queen Frederica, Helen also spent long periods in Greece and participated in the Cruise of the Kings in 1954, the marriage of Princess Sophia with the future King Juan Carlos I of Spain in 1962, and the events organized to mark the centenary of the Greek dynasty in 1963.

Despite her family commitments, Helen's life was not solely devoted to her relatives. Passionate about Renaissance architecture and painting, she spent much of her time visiting monuments and museums. She also dedicated herself to creating artistic objects, such as an engraving made with a dentist's drill on an ivory billiard ball. A gardening enthusiast, she devoted long hours to the flowers and shrubs of her residence. A regular guest of the British Consulate, she also frequented intellectuals who, like Harold Acton, had settled in the Florence region. From 1968 to 1973, Helen had a romantic relationship with the twice-widowed King Gustaf VI Adolf of Sweden, with whom she shared a love of art and plants. At one point, the Scandinavian sovereign asked her to marry him, but she refused.

5.4. Financial Difficulties and Later Life

In 1956, Helen consented to Arthur Gould Lee publishing her biography. At this point, her life was marked by financial difficulties that continued to worsen over time. Despite still being deprived of income by the Romanian authorities, the queen mother economically supported her son and also helped him find jobs, first as a pilot in Switzerland, then as a broker on Wall Street. Helen also supported the studies of her eldest granddaughter Margareta, and even welcomed her at Villa Sparta for a year before she entered a British university. To do this, Helen was forced to sell her assets one by one, and by the early 1970s, she had hardly anything left. In 1973, she mortgaged her residence, and three years later, she sold the two Greco paintings that she had brought with her from Romania in 1947.

5.5. Death

Becoming too old to live alone, Helen finally left Fiesole in 1979. She then moved to a small apartment in Lausanne, located 45 minutes from the residence of Michael I and Anne, before moving in with them at Versoix in 1981. Helen, Queen Mother of Romania, died one year later on November 28, 1982, aged 86. She was buried without pomp in the Bois-de-Vaux Cemetery, and the funerals were celebrated by Damaskinos Papandreou, the first Greek Orthodox Metropolitan of Switzerland.

6. Legacy and Recognition

Helen's enduring impact is primarily defined by her moral courage and humanitarian actions during World War II, which led to her significant posthumous recognition and a reevaluation of her place in history.

6.1. Recognition as Righteous Among the Nations

Eleven years after her death, in March 1993, the State of Israel bestowed upon Helen the title of Righteous Among the Nations in recognition of her actions during World War II concerning Romanian Jews. She managed to save several thousands of them from 1941 to 1944. The announcement was made to the royal family by Alexandru Șafran, then Chief Rabbi of Geneva. This honor emphasizes her exceptional moral courage and the profound impact of her interventions during the Holocaust.

6.2. Reburial and Commemoration

In January 2018, it was announced that the remains of King Carol II would be moved to the new Archdiocesan and Royal Cathedral, alongside those of Queen Mother Helen. Additionally, the remains of Prince Mircea would also be moved to the new cathedral from their current interment at the Bran Castle's Chapel. Queen Mother Helen of Romania was reburied at the New Episcopal and Royal Cathedral in Curtea de Argeș on October 19, 2019.