1. Overview

George Frost Kennan was a prominent American diplomat, political scientist, and historian, best known as the architect of the containment policy against Soviet expansion during the Cold War. Born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1904, Kennan's career spanned extensive diplomatic service and a long academic tenure at the Institute for Advanced Study. His influential "Long Telegram" from Moscow in 1946 and the subsequent "X" article in 1947 articulated the core strategy of containment, arguing that the Soviet regime was inherently expansionist and its influence needed to be countered at vital strategic points.

Despite his foundational role in shaping U.S. Cold War policy, Kennan soon became a vocal critic of the very policies he helped initiate, particularly as containment became increasingly militarized. He opposed the arms race, the Vietnam War, and NATO enlargement, advocating for a more pragmatic and less ideological approach to international relations rooted in political realism. His later career was marked by prolific scholarly work and public commentary, often challenging conventional American foreign policy and domestic trends. Kennan passed away in 2005 at the age of 101, leaving behind a complex legacy as one of the 20th century's most influential, yet often dissenting, diplomatic thinkers.

2. Life

George F. Kennan's life was a journey from a challenging childhood through a distinguished diplomatic career that shaped American foreign policy, culminating in a long and influential academic tenure where he became a prominent critic of the nation's international engagements.

2.1. Early Childhood and Education

George Frost Kennan was born on February 16, 1904, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Kossuth Kent Kennan, a tax law specialist, and Florence James Kennan. His father's family descended from impoverished Scots-Irish settlers in 18th-century Connecticut and Massachusetts. Tragically, his mother died from peritonitis just two months after his birth, a fact Kennan long believed was directly related to his birth, and he often lamented her absence throughout his life. He was not close to his father or stepmother but maintained strong bonds with his older sisters.

At the age of eight, Kennan traveled to Germany to stay with his stepmother in Kassel for six months to learn German. During the summers of 1915 and 1916, he attended Camp Highlands in Sayner, Wisconsin. He later attended St. John's Northwestern Military Academy in Delafield, Wisconsin, before enrolling at Princeton University in the latter half of 1921. A shy and introverted individual, Kennan found his undergraduate years at the elite Ivy League institution challenging and isolating, as he was unaccustomed to its atmosphere. He earned his bachelor's degree in history in 1925.

2.2. Beginning of Diplomatic Career

After graduating from Princeton, Kennan initially considered law school but found the costs prohibitive. He instead applied to the newly established United States Foreign Service. After passing the qualifying examination and completing seven months of study at the Foreign Service School in Washington, D.C., he secured his first diplomatic post as a vice consul in Geneva, Switzerland. Within a year, he was transferred to Hamburg, Germany, and in 1928, to Tallinn, Estonia, as a third secretary responsible for Baltic Sea affairs.

In 1928, contemplating resignation from the Foreign Service to pursue graduate studies, Kennan was instead selected for a linguist training program. This allowed him three years of graduate-level study without leaving the service. In 1929, he began an intensive program in history, politics, culture, and the Russian language at the Oriental Institute of the University of Berlin. He followed in the footsteps of his grandfather's younger cousin, also named George Kennan (1845-1924), a noted 19th-century expert on Imperial Russia and author of Siberia and the Exile System. Throughout his diplomatic career, Kennan became fluent in several other languages, including German, French, Polish, Czech, Portuguese, and Norwegian.

In 1931, Kennan was stationed at the legation in Riga, Latvia, where he focused on Soviet economic affairs, deepening his interest in Russian matters. When the U.S. established formal diplomatic relations with the Soviet government in 1933 following President Franklin D. Roosevelt's election, Kennan accompanied Ambassador William C. Bullitt to Moscow, serving there until 1937. By the mid-1930s, he was among the professionally trained Russian experts at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, alongside Charles E. Bohlen and Loy W. Henderson. These officials harbored skepticism about cooperation with the Soviet Union, even against common adversaries. During this period, Kennan closely observed Joseph Stalin's Great Purge, which profoundly shaped his lifelong views on the internal dynamics of the Soviet regime.

2.3. Diplomatic Activities during World War II

Kennan found himself in strong disagreement with Joseph E. Davies, Bullitt's successor as ambassador to the Soviet Union, who defended the Great Purge and other aspects of Stalin's rule. Kennan had no influence on Davies' decisions, and Davies even suggested Kennan be transferred out of Moscow for "his health." Kennan again considered resigning but instead accepted a position at the Russian desk in the State Department in Washington. In a 1935 letter to his sister Jeannette, Kennan expressed his disillusionment with American life, stating, "I hate the rough and tumble of our political life. I hate democracy; I hate the press... I hate the 'peepul'; I have become clearly un-American."

By September 1938, Kennan was reassigned to the legation in Prague. After Nazi Germany occupied the First Czechoslovak Republic at the beginning of World War II, Kennan was assigned to Berlin. There, he supported the United States' Lend-Lease policy but cautioned against any American endorsement of the Soviets, whom he considered unreliable allies. He was interned in Germany for six months after Germany, followed by other Axis powers, declared war on the United States in December 1941. He returned to the U.S. in May 1942.

In September 1942, Kennan was assigned to the legation in Lisbon, Portugal, where he reluctantly managed intelligence and base operations. In July 1943, when Ambassador Bert Fish died suddenly, Kennan became chargé d'affaires and head of the American Embassy in Portugal. While in Lisbon, Kennan played a decisive role in securing Portugal's approval for the use of the Azores Islands by American naval and air forces during World War II. Despite initial clumsy instructions and a lack of coordination from Washington, Kennan took the initiative by personally communicating with President Roosevelt, obtaining a letter from the President to Portuguese Premier António de Oliveira Salazar, which facilitated the concession of facilities in the Azores.

In January 1944, he was sent to London, serving as counselor of the American delegation to the European Advisory Commission, which aimed to prepare Allied policy in Europe. Here, Kennan grew further disillusioned with the State Department, believing it overlooked his expertise as a trained specialist. However, within months, he was appointed deputy chief of mission in Moscow at the request of W. Averell Harriman, the ambassador to the USSR.

2.4. Design of Cold War Policy: Formation of Containment

In Moscow, Kennan again felt his opinions were being disregarded by President Truman and policymakers in Washington. He repeatedly tried to persuade policymakers to abandon plans for cooperation with the Soviet government in favor of a sphere of influence policy in Europe, aimed at reducing Soviet power. Kennan believed a federation needed to be established in Western Europe to counter Soviet influence and compete with the Soviet stronghold in Eastern Europe.

Kennan served as deputy head of mission in Moscow until April 1946. Towards the end of his term, the Treasury Department requested an explanation for recent Soviet behavior, such as their reluctance to endorse the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Kennan responded on February 22, 1946, by sending a lengthy 5,363-word telegram (sometimes cited as over 8,000 words), known as "The Long Telegram", from Moscow to Secretary of State James F. Byrnes. This telegram outlined a new strategy for diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. The ideas were not entirely new, but Kennan's forceful argument and vivid language arrived at an opportune moment. He argued that at the "bottom of the Kremlin's neurotic view of world affairs is the traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity." After the Russian Revolution, this insecurity merged with communist ideology and "Oriental secretiveness and conspiracy."

Kennan asserted that Soviet international behavior was primarily driven by the internal necessities of Joseph Stalin's regime, which required a hostile world to legitimize its autocratic rule. Stalin, according to Kennan, used Marxism-Leninism as a "justification for the Soviet Union's instinctive fear of the outside world, for the dictatorship without which they did not know how to rule, for cruelties they did not dare not to inflict, for sacrifice they felt bound to demand... Today they cannot dispense with it. It is the fig leaf of their moral and intellectual respectability." The solution, Kennan proposed, was to strengthen Western institutions to make them invulnerable to the Soviet challenge, while awaiting the eventual "mellowing" of the Soviet regime. He emphasized the vital role of propaganda and culture, stressing that America must present itself effectively to foreign audiences while the Soviets would restrict cultural exchange.

Kennan's new policy, later termed "containment" in his "X" article, stipulated that Soviet pressure had to "be contained by the adroit and vigilant application of counterforce at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points." The ultimate goal of this policy was the withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Europe, leading to a settlement that would reassure the Kremlin against hostile regimes in Eastern Europe, thereby tempering the degree of control the Soviet leaders felt necessary to exercise over that area.

The "Long Telegram" brought Kennan to the attention of James Forrestal, then Secretary of the Navy and a strong advocate for a confrontational policy with the Soviets. Forrestal helped bring Kennan back to Washington, where he served as the first deputy for foreign affairs at the National War College and was strongly influenced to publish the "X" article.

In July 1947, Kennan's article, "The Sources of Soviet Conduct", appeared in Foreign Affairs under the pseudonym "X." Unlike the "Long Telegram," this article did not begin by emphasizing the "traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity." Instead, it asserted that Stalin's policy was shaped by a combination of Marxist-Leninist ideology, which advocated revolution to defeat capitalism, and Stalin's determination to use the notion of "capitalist encirclement" to legitimize his regimentation of Soviet society and consolidate his political power. Kennan argued that Stalin would not and could not moderate the Soviet determination to overthrow Western governments. Therefore, "the main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.... Soviet pressure against the free institutions of the Western world is something that can be contained by the adroit and vigilant application of counterforce at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points, corresponding to the shifts and manœuvres of Soviet policy, but which cannot be charmed or talked out of existence." He further argued that the U.S. would have to perform this containment alone, but if it could do so without undermining its own economic health and political stability, the Soviet party structure would eventually undergo immense strain, leading to "either the break-up or the gradual mellowing of Soviet power."

The publication of the "X" article ignited a major Cold War debate. Walter Lippmann, a leading American commentator, harshly criticized it as a "strategic monstrosity" that could only be implemented by supporting a "heterogeneous array of satellites, clients, dependents, and puppets." Lippmann advocated for diplomacy, suggesting a U.S. withdrawal from Europe and a reunified, demilitarized Germany. Soon after, it was informally revealed that "X" was Kennan, giving the article the status of an official expression of the Truman administration's new policy.

Kennan, however, later clarified that he had not intended the "X" article as a rigid policy prescription. For the rest of his life, he reiterated that the article did not imply an automatic commitment to resist Soviet "expansionism" everywhere, without distinguishing between primary and secondary interests. He emphasized that he favored political and economic, rather than military, methods for containment. In a 1996 interview with CNN, Kennan stated, "My thoughts about containment were of course distorted by the people who understood it and pursued it exclusively as a military concept; and I think that that, as much as any other cause, led to [the] 40 years of unnecessary, fearfully expensive and disoriented process of the Cold War." He clarified that he did not view the Soviets as primarily a military threat, noting, "they were not like Hitler." This misunderstanding, he felt, stemmed from a single sentence in the "X" article. The "X" article brought Kennan sudden fame, ending his "official loneliness" and giving his voice significant weight.

Between April 1947 and December 1948, under Secretary of State George C. Marshall, Kennan reached the peak of his influence. Marshall valued his strategic insight and appointed him to create and direct the Policy Planning Staff, the State Department's internal think tank, making him its first director. Marshall heavily relied on Kennan for policy recommendations, and Kennan played a central role in drafting the Marshall Plan.

Although Kennan considered the Soviet Union too weak to risk war, he viewed it as an ideological and political rival capable of expanding into Western Europe through subversion, given the popular support for Communist parties in war-devastated Western Europe. To counter this, Kennan proposed economic aid and covert political support to Japan and Western Europe to revive their governments and assist international capitalism, thereby rebuilding the balance of power. In June 1948, he suggested covert assistance to non-Moscow-aligned left-wing parties and labor unions in Western Europe to create a rift between Moscow and Western European working-class movements. In 1947, he supported Truman's economic aid to the Greek government fighting communist guerrillas but argued against military aid, believing Greece was not strategically vital enough to risk war with the Soviet Union.

As the U.S. initiated the Marshall Plan, Kennan and the Truman administration hoped the Soviet Union's rejection of aid would strain its relations with Eastern European allies. Kennan initiated efforts to exploit the schism between the Soviets and Tito's Yugoslavia, proposing covert action in the Balkans to further diminish Moscow's influence. The administration's anti-Soviet policy also led to a shift in U.S. hostility towards Francisco Franco's anti-communist regime in Spain, at Kennan's suggestion, to secure U.S. influence in the Mediterranean, leading to military cooperation after 1950. Kennan played an important role in designing American economic aid plans for Greece, emphasizing a capitalist development model and economic integration with Europe. While Marshall Plan aid successfully rebuilt infrastructure in Greece, attempts to impose "good government" were less successful due to the entrenched rentier system controlled by a few wealthy families and the royal family. Kennan's advice to open the Greek economy was largely ignored by the Greek elite. He initially supported France's efforts to regain control of Vietnam, seeing Southeast Asia's raw materials as critical for Western Europe and Japan's economic recovery. However, by 1949, he became convinced that the French could not defeat the Communist Viet Minh guerrillas.

In 1949, Kennan proposed "Program A" or "Plan A" for the reunification of Germany, arguing that its partition was unsustainable. He predicted that American people would tire of occupying their zone or that Soviets would withdraw from East Germany (knowing they could easily return from Poland), forcing the U.S. to do the same, which would disadvantage the U.S. due to lack of Western European bases. He also argued that proud Germans would not tolerate foreign occupation indefinitely. Kennan's solution called for the reunification and neutralization of Germany, the withdrawal of most British, American, French, and Soviet forces (except small border enclaves), and a four-power commission to oversee a largely self-governing Germany.

2.5. Criticism of Policy and Shift in Influence

Kennan's influence waned significantly when Dean Acheson succeeded the ailing George Marshall as Secretary of State in 1949. Acheson did not primarily view the Soviet "threat" as political, seeing events like the Berlin Blockade (June 1948), the first Soviet nuclear test (August 1949), the Chinese Communist Revolution (October 1949), and the Korean War (June 1950) as evidence of a military threat. Truman and Acheson opted to define the Western sphere of influence and establish a system of alliances. Kennan, however, argued that mainland Asia should be excluded from containment policies, believing the United States was "greatly overextended in its whole thinking about what we can accomplish and should try to accomplish" in Asia. He instead proposed that Japan and the Philippines serve as the "cornerstone of a Pacific security system."

Acheson initially approved Program A for Germany, noting that the "division of Germany was not an end onto itself." However, Plan A faced strong objections from the Pentagon, who viewed it as abandoning West Germany to the Soviet Union, and from within the State Department, with diplomat Robert Murphy arguing that a prosperous, democratic West Germany would destabilize East Germany. Crucially, neither the British nor French governments supported Program A, considering it too early to end the occupation of Germany due to public fears of loosening control just four years after World War II. In May 1949, a distorted version of Plan A was leaked to the French press, suggesting the U.S. was willing to withdraw from all of Europe for a reunified, neutral Germany. This caused an uproar, leading Acheson to disavow Plan A.

Kennan resigned as Director of Policy Planning in December 1949 but remained as counselor until June 1950. In January 1950, Acheson replaced Kennan with Paul Nitze, who was more comfortable with military power calculations. Afterwards, Kennan accepted an appointment as a Visitor to the Institute for Advanced Study from its director, J. Robert Oppenheimer. The "Loss of China" to the Chinese Communists under Mao Zedong in October 1949 sparked a fierce right-wing backlash in the U.S., led by politicians like Richard Nixon and Joseph McCarthy, who used it to attack the Truman administration. Kennan and other high officials were accused of negligence. His close friend, diplomat John Paton Davies Jr., came under investigation as a Soviet spy for predicting Mao's victory, which devastated his career and horrified Kennan, who warned, "We have no protection against this happening again."

Kennan found the atmosphere of hysteria, dubbed "McCarthyism" in March 1950, deeply uncomfortable. Acheson's policy was formalized as NSC 68, a classified report issued in April 1950 and written by Nitze. Kennan and Charles E. Bohlen, another State Department expert on Russia, debated NSC-68's wording. Kennan rejected the idea of Stalin having a grand design for world conquest, arguing that Stalin actually feared overextending Russian power. He believed NSC-68 should not have been drafted at all, as it would make U.S. policies too rigid, simplistic, and militaristic. Acheson, however, overruled Kennan and Bohlen, endorsing the assumption of Soviet menace in NSC-68.

Kennan opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb and the rearmament of Germany, policies encouraged by NSC-68's assumptions. During the Korean War (which began in June 1950), when rumors circulated about advancing beyond the 38th parallel into North Korea-an act Kennan considered dangerous-he intensely argued with Assistant Secretary of State for the Far East Dean Rusk, who seemed to support Acheson's goal of forcibly uniting the Koreas. Kennan supported the initial decision to intervene in Korea, but believed the political goal should be to restore the status quo. He opposed crusades to liberate people from communist tyranny and advised that U.S. forces should not cross the 38th parallel. He argued that American policies during the Korean War were based on "emotional, moralistic attitudes" which, "unless corrected, can easily carry us toward real conflict with the Russians and inhibit us from making a realistic agreement about that area." He supported intervention in Korea but stated, "it is not essential to us to see an anti-Soviet Korean regime extended to all of Korea."

On August 21, 1950, Kennan submitted a lengthy memo to John Foster Dulles, then working on the U.S.-Japanese peace treaty, outlining his broader thoughts on Asia. He described U.S. policy thinking on Asia as "little promising" and "fraught with danger." Kennan expressed significant concern about General Douglas MacArthur's "wide and relatively uncontrolled latitude" in determining policy in North Asia and the Western Pacific, viewing MacArthur's judgment as poor.

Kennan's 1951 book, American Diplomacy, 1900-1950, sharply criticized American foreign policy of the preceding 50 years. He warned against U.S. participation in and reliance on multilateral, legalistic, and moralistic organizations like the United Nations. Despite his influence, Kennan never felt truly comfortable in government. He considered himself an outsider and had little patience for critics. W. Averell Harriman observed that Kennan "understood Russia but not the United States."

Kennan's fundamental concept for foreign policy was his "five industrialized zones," control of which would determine the dominant world power: the United States, Great Britain, the Rhine River valley (Rhineland, Ruhr, eastern France, Low Countries), the Soviet Union, and Japan. He argued that if the industrialized zones outside the Soviet Union aligned with the U.S., then America would be the dominant power. Thus, "containment" primarily applied to controlling these zones. Kennan held considerable disdain for the peoples of the Third World, viewing European rule over much of Asia and Africa as natural. While common among U.S. officials in the late 1940s, Kennan's retention of these views was unusual, as many by the 1950s felt that American prejudice against non-white peoples harmed the U.S. image globally, benefiting the Soviet Union. Kennan generally believed the U.S. should not be involved in the Third World, seeing little of value there. Exceptions included Latin America, which he considered within the American sphere of influence, believing Washington should warn Latin American leaders "not to wander too far from our side." Acheson was so offended by a March 1950 report by Kennan, which suggested that miscegenation among Europeans, Indians, and African slaves was the root cause of Latin America's economic backwardness, that he refused to distribute it within the State Department. Kennan also believed the oil of Iran and the Suez Canal were vital to the West, recommending U.S. support for Britain against Mohammad Mosaddegh and Mostafa El-Nahas's demands for control over the Iranian oil industry and the Suez Canal, respectively. He wrote that Abadan and the Suez Canal were economically crucial for the West, justifying the use of "military strength" by Western powers to maintain control.

2.6. Major Ambassadorial Roles

Kennan held two significant ambassadorial roles during his career, offering him direct engagement with the Cold War's complexities on the ground.

2.6.1. Ambassador to the Soviet Union

In December 1951, President Truman nominated Kennan as the next U.S. ambassador to the USSR, a nomination strongly endorsed by the Senate. To Kennan's dismay, the administration's priorities emphasized creating alliances against the Soviets more than negotiating differences. In his memoirs, Kennan recalled that the U.S. seemed to expect to achieve its objectives "without making any concessions though, only 'if we were really all-powerful, and could hope to get away with it.' I very much doubted that this was the case."

Upon his arrival in Moscow, Kennan found the atmosphere even more regimented than during his previous postings. Police guards followed him everywhere, discouraging any contact with Soviet citizens. At the time, Soviet propaganda accused the U.S. of preparing for war, a charge Kennan did not entirely dismiss. He began to question whether the U.S. had "contributed... by the overmilitarization of our policies and statements... to a belief in Moscow that it was war we were after, that we had settled for its inevitability, that it was only a matter of time before we would unleash it."

In September 1952, Kennan made a statement that ultimately cost him his ambassadorship. In response to a question at a press conference, he compared his living conditions at the ambassador's residence in Moscow to those he had experienced while interned in Berlin during the early months of hostilities between the United States and Germany. Although his statement was not entirely unfounded, the Soviets interpreted it as an implied analogy with Nazi Germany. Consequently, the Soviets declared Kennan persona non grata and refused to allow him to re-enter the USSR. Kennan later acknowledged it was a "foolish thing for me to have said."

2.6.2. Ambassador to Yugoslavia

During John F. Kennedy's 1960 presidential campaign, Kennan wrote to the future president offering suggestions for improving U.S. foreign affairs. He advised a series of "calculated steps, timed in such a way as not only to throw the adversary off balance but to keep him off it, and prepared with sufficient privacy so that the advantage of surprise can be retained." He also urged the administration to "assure a divergence of outlook and policy between the Russians and Chinese," which he believed could be achieved by improving relations with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, who sought to distance himself from Communist China. Kennan wrote, "We should... without deceiving ourselves about Khrushchev's political personality and without nurturing any unreal hopes, be concerned to keep him politically in the running and and to encourage the survival in Moscow of the tendencies he personifies." Additionally, he recommended that the United States work to create divisions within the Soviet bloc by undermining its power in Eastern Europe and encouraging the independent tendencies of satellite governments.

Although Kennan had not been considered for a position by Kennedy's advisers, the president personally offered him the choice of ambassadorships in either Poland or Yugoslavia. Kennan, more interested in Yugoslavia, accepted Kennedy's offer and began his tenure in Belgrade in May 1961.

His primary task was to strengthen Yugoslavia's policy against the Soviets and encourage other Eastern Bloc states to pursue autonomy from Moscow. Kennan found his ambassadorship in Belgrade a significant improvement over his experiences in Moscow a decade earlier. He noted, "I was favored in being surrounded with a group of exceptionally able and loyal assistants, whose abilities I myself admired, whose judgment I valued, and whose attitude toward myself was at all times... enthusiastically cooperative... Who was I to complain?" He observed that the Yugoslav government treated American diplomats politely, a stark contrast to his treatment by the Russians in Moscow. He wrote that the Yugoslavs "considered me, rightly or wrongly, a distinguished person in the U.S., and they were pleased that someone whose name they had heard before was being sent to Belgrade."

However, Kennan found his job in Belgrade challenging. President Josip Broz Tito and his foreign minister, Koča Popović, suspected that Kennedy would adopt an anti-Yugoslav policy. Tito and Popović viewed Kennedy's decision to observe Captive Nations Week as an indication that the U.S. would support anti-communist liberation efforts in Yugoslavia. Tito also believed that the CIA and the Pentagon were the true directors of American foreign policy. Kennan attempted to restore Tito's confidence in the American foreign policy establishment, but his efforts were undermined by diplomatic blunders such as the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the U-2 spy incident.

Relations between Yugoslavia and the United States quickly deteriorated. In September 1961, Tito hosted a conference of nonaligned nations, where he delivered speeches that the U.S. government interpreted as pro-Soviet. According to historian David Mayers, Kennan argued that Tito's perceived pro-Soviet policy was in fact a ploy to "buttress Khrushchev's position within the Politburo against hardliners opposed to improving relations with the West and against China, which was pushing for a major Soviet-U.S. showdown." This policy also earned Tito "credit in the Kremlin to be drawn upon against future Chinese attacks on his communist credentials." While politicians and government officials grew concerned about Yugoslavia's relationship with the Soviets, Kennan believed that the country's "anomalous position in the Cold War... objectively suited U.S. purposes." He also believed that within a few years, Yugoslavia's example would inspire other Eastern Bloc states to demand greater social and economic autonomy from the Soviets.

By 1962, Congress had passed legislation to deny financial aid to Yugoslavia, withdraw the sale of spare parts for Yugoslav warplanes, and revoke the country's most favored nation status. Kennan strongly protested this legislation, arguing it would only strain U.S.-Yugoslav relations. He traveled to Washington in the summer of 1962 to lobby against the legislation but was unsuccessful. President Kennedy privately endorsed Kennan's views but remained publicly noncommittal to avoid jeopardizing his slim majority in Congress on a potentially contentious issue.

In a lecture to the U.S. embassy staff in Belgrade on October 27, 1962, Kennan strongly supported Kennedy's policies during the Cuban Missile Crisis, asserting that Cuba remained within the American sphere of influence, justifying the U.S. placement of missiles in Turkey while making Soviet missiles in Cuba illegitimate. He called Fidel Castro's regime "one of the bloodiest dictatorships the world has seen in the entire postwar period," which he felt justified Kennedy's efforts to overthrow the Communist Cuban government.

In December 1962, when Tito visited Moscow to meet Khrushchev, Kennan reported to Washington that Tito was a Russophile, having lived in Russia between 1915 and 1920, and still held sentimental memories of the 1917 Russian Revolution that converted him to Communism. However, Kennan observed that Tito was firmly committed to keeping Yugoslavia neutral in the Cold War, and his expressions of affection for Russian culture did not mean he wanted Yugoslavia back in the Soviet bloc. According to Kennan, the Sino-Soviet split prompted Khrushchev to seek reconciliation with Tito to counter Chinese accusations that the Soviet Union was a bullying imperialist power. Tito, in turn, accepted improved relations with the Soviet Union to enhance his bargaining power with the West. Kennan also described Tito's championing of the Non-Aligned Movement as a way to improve Yugoslavia's bargaining power with both West and East, allowing him to cast himself as a world leader speaking for an important bloc of nations, rather than based on the movement's "intrinsic value" (which was minimal, as most non-aligned nations were poor Third World countries). Senior Yugoslav officials, Kennan reported to Washington, had told him that Tito's speeches praising the non-aligned movement were merely diplomatic posturing not to be taken too seriously.

However, many in Congress did take Tito's speeches seriously, concluding that Yugoslavia was an anti-Western nation, much to Kennan's chagrin. Kennan argued that since Tito desired Yugoslavia to be neutral, expecting alignment with the West was futile. However, Yugoslav neutrality served American interests by ensuring Yugoslavia's powerful army was not at the Soviets' disposal and that the Soviet Union had no air or naval bases in Yugoslavia that could threaten Italy and Greece, both NATO members. More importantly, Kennan noted that Yugoslavia's "market socialism" provided a higher standard of living than elsewhere in Eastern Europe, and there was greater freedom of expression than in other Communist nations. The very existence of a Communist nation in Eastern Europe not under Kremlin control was highly destabilizing to the Soviet bloc, inspiring other communist leaders to seek greater independence. With U.S.-Yugoslav relations progressively worsening, Kennan tendered his resignation as ambassador in late July 1963.

3. Academic Career and Later Life

After the end of his brief ambassadorial post in Yugoslavia in 1963, Kennan spent the remainder of his life in academia, becoming a major realist critic of U.S. foreign policy. Having previously spent 18 months as a scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) between 1950 and 1952, Kennan officially joined the faculty of the institute's School of Historical Studies in 1956, where he remained for the rest of his career, becoming an honorary professor. He was also a founding council member of the Rothermere American Institute at Oxford University.

3.1. Opposition to the Vietnam War

During the 1960s, Kennan became a vocal critic of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, arguing that the United States had little vital interest in the region. In February 1966, he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee at the request of its chairman, Senator J. William Fulbright. Kennan stated that the "preoccupation" with Vietnam was undermining U.S. global leadership and accused the Johnson administration of distorting his containment policies into a purely military approach. President Johnson, annoyed by the hearings, attempted to overshadow them by holding a sudden summit in Honolulu on February 5, 1966, with Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Nguyễn Cao Kỳ of South Vietnam, where he declared excellent progress and commitment to reforms in Vietnam.

Kennan testified that if the United States were not already fighting in Vietnam, "I would know of no reason why we should wish to become so involved, and I could think of several reasons why we should wish not to." While he opposed an immediate, disorderly withdrawal, stating it "could represent in present circumstances a disservice to our own interests, and even to world peace," he added that "there is more respect to be won in the opinion of this world by a resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions than by the most stubborn pursuit of extravagant and unpromising objectives." In his testimony, Kennan argued that Ho Chi Minh was "not Hitler" and that all he had read suggested Ho was a Communist but also a Vietnamese nationalist who did not want his country subservient to either the Soviet Union or China. He further testified that defeating North Vietnam would incur a human cost "for which I would not like to see this country be responsible for." Kennan famously compared the Johnson administration's policy towards Vietnam to "an elephant frightened by a mouse."

Kennan concluded his testimony by quoting John Quincy Adams: "America goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own." He then stated, "Now, gentlemen, I don't know exactly what John Quincy Adams had in mind when he spoke those words. But I think that, without knowing it, he spoke very directly and very pertinently to us here today." The hearings, aired live on television (a rare occurrence then), garnered significant media attention due to Kennan's reputation as the "Father of Containment." Johnson pressured major television networks not to air Kennan's testimony, leading CBS to air reruns of I Love Lucy while Kennan testified, prompting CBS director Fred Friendly to resign in protest. NBC, however, resisted presidential pressure and aired the proceedings. To counter Kennan, Johnson sent Secretary of State Dean Rusk to testify that the Vietnam War was a morally just struggle against "the steady extension of Communist power through force and threat."

Despite expectations, Kennan's testimony attracted high television ratings. He recalled receiving a flood of letters afterward, noting, "It was perfectly tremendous. I haven't expected anything remotely like this." Columnist Art Buchwald was surprised his wife and her friends watched Kennan instead of soap operas, realizing American housewives were interested in such matters. Fulbright's biographer noted that Kennan's testimony, along with that of General James M. Gavin, was crucial because they were not "irresponsible students or a wild-eyed radicals," making it acceptable for "respectable people" to oppose the Vietnam War. Kennan's February 1966 testimony was his most successful effort to influence public opinion after leaving the State Department. Before his appearance, 63% of Americans approved of Johnson's handling of the war; afterward, approval dropped to 49%.

3.2. Critic of the Counterculture

Kennan's opposition to the Vietnam War did not translate into sympathy for the student protests against it. In his 1968 book Democracy and the Student Left, Kennan attacked the left-wing university students demonstrating against the Vietnam War as violent and intolerant. He compared the "New Left" students of the 1960s to the Narodniks (populist) student radicals of 19th-century Russia, accusing both of being arrogant elitists whose ideas were fundamentally undemocratic and dangerous. Kennan wrote that most of the student radicals' demands were "gobbledygook" and charged that their political style lacked humor, exhibited extremist tendencies, and was driven by mindless destructive urges. While conceding that the students were right to oppose the Vietnam War, he complained they confused policy with institutions, arguing that a misguided policy did not make an institution inherently evil or worthy of destruction.

Kennan attributed the student radicalism of the late 1960s to what he called the "sickly secularism" of American life, which he charged was too materialistic and shallow to allow understanding of the "slow powerful process of organic growth" that had made America great. He wrote that this spiritual malaise had created a generation of young Americans with an "extreme disbalance in emotional and intellectual growth." Kennan concluded his book by lamenting that the America of his youth no longer existed, complaining that most Americans were seduced by advertising into a consumerist lifestyle, leaving them indifferent to environmental degradation and political corruption. He argued that he was the true radical, stating, "They haven't seen anything yet. Not only do my apprehensions outclass theirs, but my ideas of what would have to be done to put things right are far more radical than theirs."

In a speech delivered in Williamsburg on June 1, 1968, Kennan criticized authorities for an "excess of tolerance" in dealing with student protests and riots by African Americans. He called for the suppression of the New Left and Black Power movements in a way that would be "answerable to the voters only at the next election, but not to the press or even the courts." Kennan advocated for "special political courts" to try New Left and Black Power activists, asserting this was the only way to save the United States from chaos. At the same time, Kennan stated that based on his visits to South Africa, "I have a soft spot in my mind for apartheid, not as practiced in South Africa, but as a concept." While he disliked the petty, humiliating aspects of apartheid, he praised the "deep religious sincerity" of the Afrikaners, whose Calvinism he shared, while dismissing the capacity of South African blacks to govern their country. In 1968, Kennan argued that a system similar to apartheid was needed for the United States, as he doubted the ability of the average black American male to operate "in a system he neither understands nor respects," leading him to advocate for Bantustan-like areas in the United States to be set aside for African Americans. Kennan did not approve of the social changes of the 1960s. During a 1970 visit to Denmark, he encountered a youth festival, which he described with disgust as "swarming with hippies-motorbikes, girl-friends, drugs, pornography, drunkenness, noise. I looked at this mob and thought how one company of robust Russian infantry would drive it out of town."

3.3. Establishment of Kennan Institute

Always a dedicated student of Russian affairs, Kennan, along with Wilson Center Director James H. Billington and historian S. Frederick Starr, initiated the establishment of the Kennan Institute at the academic institution named for Woodrow Wilson. The institute is named to honor the American explorer and scholar of the Russian Empire, George Kennan (1845-1924), who was a relation of the subject of this article. Scholars at the Institute are dedicated to studying Russia, Ukraine, and the Eurasian region.

3.4. Critic of the Arms Race

By the time he published the first volume of his memoirs in 1967, Kennan argued that containment involved something other than the use of military "counterforce." He was never pleased that the policy he influenced became associated with the arms race of the Cold War. In his memoirs, Kennan contended that containment did not necessitate a militarized U.S. foreign policy. "Counterforce" implied the political and economic defense of Western Europe against the disruptive effects of war on European society. According to him, the Soviet Union, exhausted by war, posed no serious military threat to the U.S. or its allies at the beginning of the Cold War but was rather an ideological and political rival. Kennan believed that the USSR, Britain, Germany, Japan, and North America remained the areas of vital U.S. interests. During the 1970s and 1980s, particularly as détente ended under President Reagan, he became a major critic of the renewed arms race.

3.5. Politics of Silence

In 1989, President George H. W. Bush awarded Kennan the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor. Yet, he remained a realist critic of recent U.S. presidents, urging in a 1999 interview with the New York Review of Books that the U.S. government "withdraw from its public advocacy of democracy and human rights," stating that the "tendency to see ourselves as the center of political enlightenment and as teachers to a great part of the rest of the world strikes me as unthought-through, vainglorious and undesirable."

3.6. Opposition to NATO Enlargement

Despite being a key inspiration for American containment policies during the Cold War, Kennan later described NATO's enlargement as a "strategic blunder of potentially epic proportions." He opposed the Clinton administration's war in Kosovo and the expansion of NATO (the establishment of which he had also opposed half a century earlier), expressing fears that both policies would worsen relations with Russia.

During a 1998 interview with The New York Times after the U.S. Senate ratified NATO's first round of expansion, he stated "there was no reason for this whatsoever." He was concerned that it would "inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic" opinions in Russia. "The Russians will gradually react quite adversely and it will affect their policies," he said. Kennan was also troubled by talks that Russia was "dying to attack Western Europe," explaining that, on the contrary, the Russian people had revolted to "remove that Soviet regime" and that their "democracy was as far advanced" as the other countries that had just signed up for NATO then.

3.7. Last Years

Kennan remained vigorous and alert during the final years of his life, although arthritis confined him to a wheelchair. In his later years, Kennan concluded that "the general effect of Cold War extremism was to delay rather than hasten the great change that overtook the Soviet Union." At age 98, he warned of the unforeseen consequences of waging war against Iraq. He cautioned that attacking Iraq would constitute a second war "bears no relation to the first war against terrorism" and declared efforts by the Bush administration to associate Al-Qaeda with Saddam Hussein "pathetically unsupportive and unreliable." Kennan further warned: "Anyone who has ever studied the history of American diplomacy, especially military diplomacy, knows that you might start in a war with certain things on your mind as a purpose of what you are doing, but in the end, you found yourself fighting for entirely different things that you had never thought of before... In other words, war has a momentum of its own and it carries you away from all thoughtful intentions when you get into it. Today, if we went into Iraq, like the president would like us to do, you know where you begin. You never know where you are going to end."

In his final years, Kennan embraced some ideals of the Second Vermont Republic, a secessionist movement incorporated in 2003. Noting the large-scale Mexican immigration to the Southwestern United States, Kennan said in 2002 there were "unmistakable evidences of a growing differentiation between the cultures, respectively, of large southern and southwestern regions of this country, on the one hand," and those of "some northern regions." In the former, "the very culture of the bulk of the population of these regions will tend to be primarily Latin American in nature rather than what is inherited from earlier American traditions... Could it really be that there was so little of merit [in America] that it deserves to be recklessly trashed in favor of a polyglot mix-mash?" It has been argued that Kennan represented throughout his career a "tradition of militant nativism" that resembled or even exceeded the Know Nothings of the 1850s. Kennan also believed American women had too much power.

In February 2004, scholars, diplomats, and Princeton alumni gathered at the university's campus to celebrate Kennan's 100th birthday. Attendees included Secretary of State Colin Powell, international relations theorist John Mearsheimer, journalist Chris Hedges, former ambassador Jack F. Matlock, Jr., and Kennan's biographer, John Lewis Gaddis.

4. Thought and Philosophy

George F. Kennan's intellectual contributions were deeply rooted in political realism, a pragmatic approach to international relations that often put him at odds with more idealistic foreign policy trends.

4.1. Realism in International Relations

Kennan's adherence to political realism emphasized the importance of power, national interest, and the balance of power in international affairs. This school of thought, which also influenced figures like Henry Kissinger, formed the basis of Kennan's work as a diplomat and historian. Both Kennan and Kissinger advocated for a "de-emotionalized" and "cold-headed" approach to diplomacy, prioritizing national interest and avoiding impulsive actions. Their shared philosophy emphasized a pragmatic assessment of global affairs, aiming to prevent the United States from making costly mistakes or pursuing unrealistic objectives. This perspective is encapsulated in Kennan's warning: "America goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy," serving as a caution against emotional or overly aggressive foreign policy. Kissinger noted that Kennan "understood Russia but not the United States."

According to the realist tradition, security is based on the principle of a balance of power, contrasting with the idealistic or Wilsonian school of international relations, which relies on morality as the sole determining factor in statecraft and promotes the spread of democracy universally. Kennan believed that such moralism, without regard for the realities of power and national interest, was self-defeating and would lead to a decrease in American power. His concept of containment, while often interpreted militarily, was fundamentally a realist strategy aimed at maintaining a balance of power rather than engaging in a global crusade. He viewed China as a satellite state of the Soviet Union rather than an independent ally, reflecting his focus on the Soviet Union as the primary adversary in the Cold War. He was known as the "Father of Containment" and believed in strengthening the "line" against adversaries without necessarily crossing it into direct conflict.

4.2. Critique of Moralistic Diplomacy

Kennan consistently argued against foreign policies based on abstract moralism or utopian ideals, advocating instead for pragmatic and interest-based approaches. In his historical writings and memoirs, he extensively lamented the failings of democratic foreign policy makers, particularly those in the United States. He contended that when American policymakers confronted the Cold War, they had inherited a rationale and rhetoric that was "utopian in expectations, legalistic in concept, moralistic in [the] demand it seemed to place on others, and self-righteous in the degree of high-mindedness and rectitude... to ourselves."

He criticized the U.S. policy towards Japan leading up to World War II, arguing that America's disregard for Japan's economic interests and its insistence on the "Open Door" policy pushed Japan towards extremism and militarism, ultimately leading to the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Attack on Pearl Harbor. He believed that the subsequent power vacuum in Asia was then filled by the Soviet Union and Communist China, leading to a worse outcome for American interests. He stated that the U.S. "received a kind of 'ironic punishment'" for not understanding Japan's interests and for trying to simply expel Japan from the Asian continent without offering viable alternatives. He argued that U.S. policy should have considered Japan's population growth, China's weakness and instability, and practical ways to respond to Japan's ambitions, noting that Washington's attempts to thwart Japanese policy only increased the power of militarists in Tokyo. He believed that if the U.S. had adjusted its policy towards Japan, the attack on Pearl Harbor could have been avoided.

4.3. Views on Democracy and Public Opinion

Kennan held complex views on democratic governance and the role of public opinion in foreign policy, often expressing concerns about its potential for oversimplification and emotionalism. He insisted that the U.S. public could only be united behind a foreign policy goal on the "primitive level of slogans and jingoistic ideological inspiration." He believed that the source of many foreign policy problems lay in the force of public opinion, which he considered inevitably unstable, unserious, subjective, emotional, and simplistic.

He also criticized the social changes of the 1960s, attributing student radicalism and other movements to a "sickly secularism" in American life, which he saw as overly materialistic and shallow. He expressed concern about the "extreme disbalance in emotional and intellectual growth" among young Americans and lamented what he perceived as the decline of the America of his youth into a consumerist society indifferent to environmental degradation and political corruption.

5. Published Works

During his career at the Institute for Advanced Study, Kennan authored seventeen books and numerous articles on international relations, earning significant recognition for his literary contributions.

5.1. Major Books and Articles

Kennan's most significant published works include his foundational Cold War analyses and memoirs:

- "The Sources of Soviet Conduct" (published under the pseudonym "X" in Foreign Affairs, 1947)

- Policy Planning Study (PPS) 23 (1948)

- American Diplomacy, 1900-1950 (1951)

- Realities of American Foreign Policy (1954)

- Russia Leaves the War (1956)

- The Sisson Documents (1956)

- The Decision to Intervene (1958)

- Russia, the Atom, and the West (1958)

- Russia and the West under Lenin and Stalin (1961)

- On Dealing with the Communist World (1964)

- Memoirs: 1925-1950 (1967)

- From Prague after Munich: Diplomatic Papers, 1938-1939 (1968)

- Democracy and the Student Left (1968)

- The Marquis de Custine and His 'Russia in 1839' (1971)

- Memoirs: 1950-1963 (1972)

- The Cloud of Danger: Current Realities of American Foreign Policy (1978)

- Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917-1941 (1978)

- The Decline of Bismarck's European Order: Franco-Russian Relations, 1875-1890 (1979)

- The Nuclear Delusion: Soviet-American Relations in the Atomic Age (1982)

- The Fateful Alliance: France, Russia, and the Coming of the First World War (1984)

- Sketches from a Life (1989)

- Around the Cragged Hill: A Personal and Political Philosophy (1993)

- At a Century's Ending: Reflections 1982-1995 (1996)

- An American Family: The Kennans, the First Three Generations (2000)

- The Kennan Diaries (2014)

His historical works constitute a six-volume account of relations between Russia and the West from 1875 to his own time, though the period from 1894 to 1914 was planned but not completed. He was particularly concerned with the folly of World War I as a policy choice, arguing that its direct and indirect costs predictably exceeded the benefits of eliminating the Hohenzollerns. He also critiqued the ineffectiveness of summit diplomacy, citing the Conference of Versailles as a prime example, believing that national leaders are too preoccupied to give diplomatic problems the consistent and flexible attention they require. Kennan was indignant both with Soviet accounts of a vast capitalist conspiracy during the Allied intervention in Russia (1918-1919), which often omitted World War I, and with the decision to intervene, which he viewed as costly and harmful, possibly even ensuring the survival of the Bolshevik state by arousing Russian nationalism. He held a low opinion of President Roosevelt, stating in 1975 that "For all his charm, political skill, and able wartime leadership, when it came to foreign policy Roosevelt was a superficial, ignorant dilettante, a man with a severely limited intellectual horizon."

5.2. Awards for Writings

Kennan received numerous literary awards for his writings, recognizing their significant impact:

- Pulitzer Prize for History** (1957) for Russia Leaves the War

- National Book Award for Nonfiction** (1957) for Russia Leaves the War

- Bancroft Prize** (1957) for Russia Leaves the War

- Francis Parkman Prize** (1957) for Russia Leaves the War

- Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography** (1968) for Memoirs, 1925-1950

- National Book Award for Nonfiction** (1968) for Memoirs, 1925-1950

A second volume of his memoirs, covering up to 1963, was published in 1972.

6. Evaluation and Legacy

George F. Kennan's contributions to American foreign policy and international relations theory are widely acknowledged, though his views and legacy have also been subject to considerable criticism and controversy.

6.1. Positive Assessment

Kennan is widely regarded as one of the most influential diplomats of the 20th century. His foundational role in developing the containment strategy is a cornerstone of his positive assessment. When the CIA obtained the transcript of Nikita Khrushchev's "Secret Speech" attacking Stalin in May 1956, Kennan was among the first to whom the text was shown, highlighting his continued relevance to intelligence assessments. On October 11, 1956, he testified to the House Committee of Foreign Affairs that Soviet rule in Eastern Europe was "eroding more rapidly than I ever anticipated," noting that the rise of Władysław Gomułka in Poland indicated a "Titoist" direction, inspiring greater independence from Moscow.

Henry Kissinger stated that Kennan "came as close to authoring the diplomatic doctrine of his era as any diplomat in our history," while Colin Powell called him "our best tutor" in navigating 21st-century foreign policy challenges. Foreign Policy magazine described Kennan as "the most influential diplomat of the 20th century." Historian Wilson D. Miscamble remarked, "One can only hope that present and future makers of foreign policy might share something of his integrity and intelligence."

Beyond his direct policy influence, Kennan's intellectual contributions to foreign policy discourse are highly valued. He was a two-time recipient of both the Pulitzer Prizes and the National Book Award, and also received the Francis Parkman Prize, the Ambassador Book Award, and the Bancroft Prize. His other numerous awards include election to the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1952), the Testimonial of Loyal and Meritorious Service from the Department of State (1953), Princeton's Woodrow Wilson Award for Distinguished Achievement in the Nation's Service (1976), the Pour le Mérite (1976), the Albert Einstein Peace Prize (1981), the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (1982), the American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal (1984), the American Whig-Cliosophic Society's James Madison Award for Distinguished Public Service (1985), the Franklin D. Roosevelt Foundation Freedom from Fear Medal (1987), the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1989), the Distinguished Service Award from the Department of State (1994), and the Library of Congress Living Legend (2000). He also received 29 honorary degrees and was honored with the George F. Kennan Chair in National Security Strategy at the National War College and the George F. Kennan Professorship at the Institute for Advanced Study.

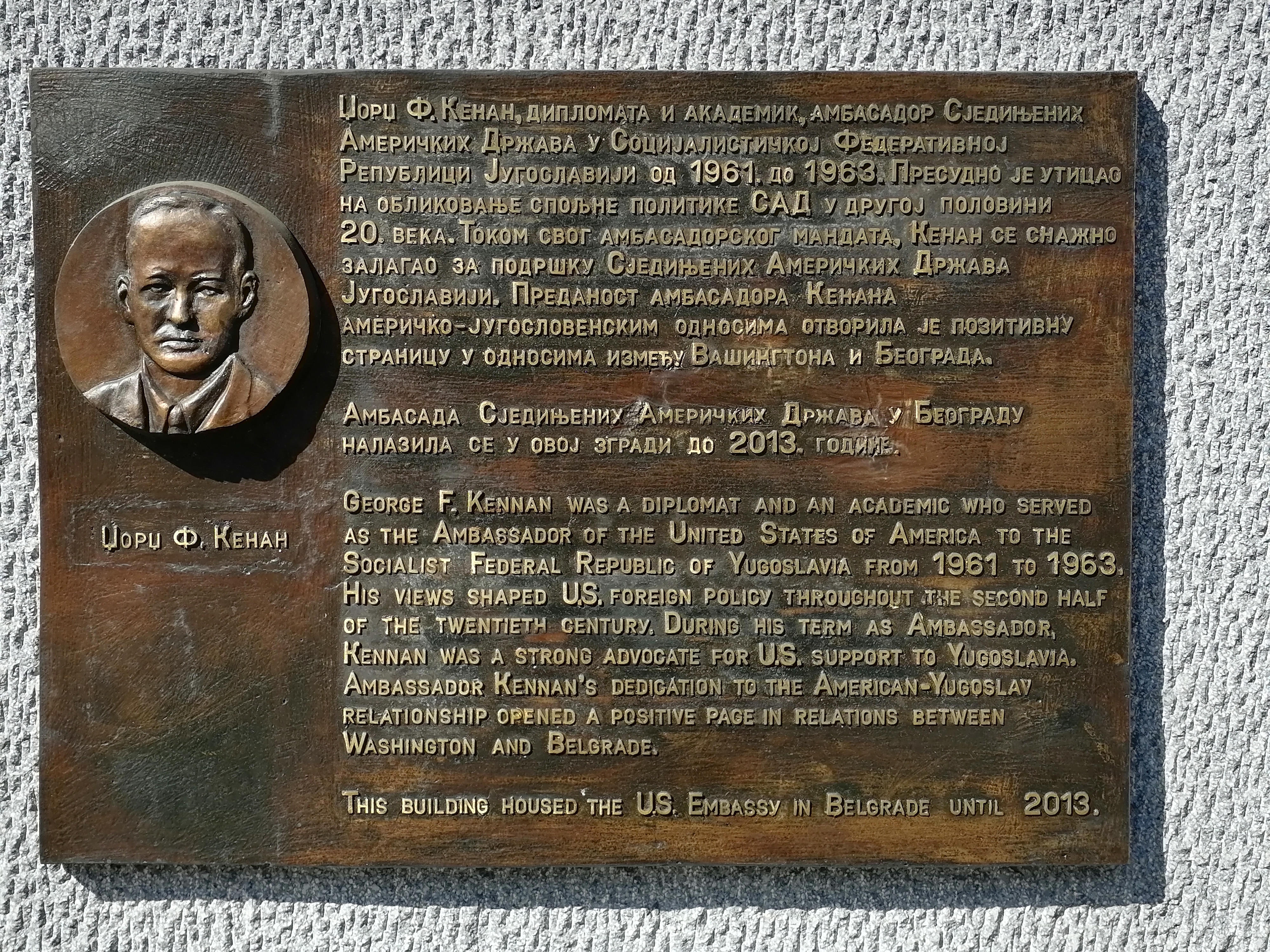

In June 2022, a memorial plaque honoring Kennan was unveiled in Belgrade, Serbia, at the site of the former U.S. embassy, where he served as ambassador from 1961 to 1963 when it was part of Yugoslavia.

6.2. Criticism and Controversy

Despite his significant contributions, Kennan's views and actions drew criticism and sparked controversy throughout his career and beyond. His "X" article, while foundational, was widely misinterpreted as advocating for a primarily military approach to containment, a misinterpretation he lamented for the rest of his life. He consistently argued that the Soviet Union posed an ideological and political challenge, not primarily a military one, and that the militarization of U.S. foreign policy was a grave error that prolonged the Cold War.

His opposition to the Vietnam War, while later seen by many as prescient, was controversial at the time, particularly his public testimony against the Johnson administration's policies. His criticisms of the nuclear arms race and his strong opposition to NATO expansion in the post-Cold War era, which he called a "strategic blunder of potentially epic proportions," were also met with resistance, especially from those who saw NATO as vital for European security. He argued that NATO expansion would "inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic" opinions in Russia, leading to adverse reactions. The West German foreign minister, Heinrich von Brentano, stated about Kennan's 1957 Reith lectures, which advocated for German reunification and neutralization, "Whoever says these things is no friend of the German people."

Beyond foreign policy, some of Kennan's views on domestic issues and social change were highly controversial and reflected deeply conservative, at times nativist, perspectives. His 1968 book Democracy and the Student Left attacked student protestors, comparing them to 19th-century Russian radicals and accusing them of being arrogant, undemocratic, and destructive. He blamed their radicalism on the "sickly secularism" and materialism of American life. More critically, in a 1968 speech, Kennan called for the suppression of the New Left and Black Power movements, advocating for "special political courts" to try activists. He expressed a "soft spot" for apartheid as a concept, praising the "deep religious sincerity" of Afrikaners while dismissing the capacity of South African blacks to govern. He even suggested a system similar to Bantustans for African Americans in the U.S., believing that average black American males could not operate "in a system he neither understands nor respects." He also expressed disdain for large-scale Mexican immigration to the Southwestern United States, fearing it would dilute American culture and lead to a "polyglot mix-mash." Critics argue that these views place him within a "tradition of militant nativism." He also believed American women had too much power.

His prediction in 1950 that supporting the Kuomintang government in Taiwan would "strengthen Peiping [Beijing]-Moscow solidarity rather than weaken it" was also a point of contention, as he advocated for giving China's seat on the United Nations Security Council to the People's Republic of China to divide the Sino-Soviet bloc.

7. Personal Life

George F. Kennan's personal life provided a backdrop to his demanding public career, marked by a lifelong marriage and family connections.

7.1. Marriage and Family

In 1931, George F. Kennan married Annelise Sorensen, a Norwegian woman. Their marriage lasted until his death. They had four children: Grace, Joan, Wendy, and Christopher. He was also survived by eight grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Annelise Sorensen Kennan passed away in 2008 at the age of 98.

8. Death

George F. Kennan died on March 17, 2005, at his home in Princeton, New Jersey, at the remarkable age of 101. His passing marked the end of an era for American diplomacy and foreign policy thought. In an obituary, The New York Times described him as "the American diplomat who did more than any other envoy of his generation to shape United States policy during the cold war" and to whom "the White House and the Pentagon turned when they sought to understand the Soviet Union after World War II."