1. Youth and Early Career

Edward Gierek's early life was shaped by his family's deep roots in the coal mining industry and his experiences as an immigrant in Western Europe, where he became involved in communist movements and resistance activities.

1.1. Early Life and Emigration

Edward Gierek was born on January 6, 1913, in Porąbka, which is now part of Sosnowiec, Poland. He came from a family with a long history in coal mining; his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all miners who died in mining accidents. When Gierek was four, his own father was killed in a pit accident. His widowed mother worked diligently to raise him and his sister. In 1920, his mother remarried, and in 1923, the family immigrated to northern France in search of work.

1.2. Work and Political Awakening in France and Belgium

In France, Edward completed primary school and began working in a coal mine at the age of 13. He joined the French Communist Party in 1931. In 1934, he was deported to Poland for organizing a strike. After completing two years of compulsory military service in Stryi, southeastern Poland (1934-1936), Gierek married Stanisława Jędrusik, but he struggled to find stable employment. The Giereks then moved to Belgium, where Edward worked in the coal mines of Waterschei. While working as a miner, he contracted pneumoconiosis, commonly known as black lung disease.

In 1939, Gierek joined the Communist Party of Belgium. During the German occupation of Belgium, he actively participated in communist resistance activities against Nazi Germany. After the war, Gierek remained politically engaged among the Polish immigrant community. He was a co-founder of the Belgian branch of the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) and served as the chairman of the National Council of Poles in Belgium, an immigrant protection organization. His background as a young worker and a skilled organizer, untainted by pre-war party factions or theoretical deviations, drew the attention of the Polish communist party headquarters in Warsaw.

2. Career in the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR)

Upon his return to Poland after World War II, Edward Gierek rapidly ascended through the ranks of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR), leveraging his mining background and pragmatic approach to build a significant power base and gain national recognition.

2.1. Return to Poland and PZPR Activities

In 1948, at the age of 35, after spending 22 years abroad, Gierek was directed by the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) authorities to return to Poland, which he did with his wife and their two sons. He began working within the Katowice district PPR organization. In December 1948, as a delegate from Sosnowiec, he participated in the PPR-PPS unification congress, which led to the establishment of the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR).

In 1949, Gierek was selected for a two-year higher party course in Warsaw. Although he was assessed as poorly suited for intellectual pursuits, he displayed high motivation for party work. In 1951, Roman Zambrowski assigned Gierek the task of restoring order at a striking coal mine. Gierek successfully resolved the situation through persuasion, avoiding the use of force. He became a member of the Sejm, the Polish parliament, in 1952. During the II Congress of the PZPR in March 1954, he was elected a member of the party's Central Committee. As chief of the Central Committee's Heavy Industry Division, he worked directly under First Secretary Bolesław Bierut in Warsaw.

In March 1956, when Edward Ochab became the party's First Secretary, Gierek was appointed a secretary of the Central Committee, despite publicly expressing doubts about his own qualifications. On June 28, 1956, he was dispatched to Poznań to address a workers' protest. Afterward, he was delegated by the Politburo to head the commission investigating the causes and course of the Poznań events. Their report, presented on July 7, blamed a hostile, foreign-inspired anti-socialist conspiracy that exploited worker discontent in Poznań enterprises. In July, Gierek became a member of the PZPR Politburo, but his tenure was brief, lasting only until October, when Władysław Gomułka replaced Ochab as First Secretary during the Polish October. Nikita Khrushchev criticized Gomułka for not retaining Gierek in the Politburo, though Gierek remained a Central Committee secretary responsible for economic affairs. He returned to the Politburo in March 1959, at the III Congress of the PZPR.

2.2. Leadership in the Katowice Region

In March 1957, in addition to his Central Committee duties, Gierek became the First Secretary of the Katowice Voivodeship PZPR organization, a position he held until 1970. He established a strong personal power base in the Katowice region, which housed the largest party organization in Poland's most industrialized province, Upper Silesia. He emerged as the nationally recognized leader of the party's young technocrat faction.

Gierek was regarded as a pragmatic, non-ideological, and economically progressive manager who maintained a distance from internal party factional struggles. However, he was also known for his subservient attitude toward Soviet leaders, serving as a source of information regarding the PZPR and its personalities. Both the industrial supremacy of the well-managed Upper Silesia territory under Gierek and his cultivated special relationship with the Soviets led many to believe he was a likely successor to Gomułka. Mieczysław Maneli, a law professor at Warsaw University who knew Gierek, described him in 1971 as an "old-fashioned Communist, but without fanaticism or zealousness. His Marxism is encumbered by few dogmas. It is almost pragmatic. He believes profoundly in the leading role that history conferred upon Communist parties and lives by the maxim that a government should be strong and rule unshakably." Gierek's party nickname was 'Tshombe,' and Silesia was referred to as the 'Polish Katanga,' where he operated almost as a sovereign prince, known for his talent as an organizer and his ability to find efficient and loyal subordinates across various professions, including engineers, economists, professors, writers, party apparatchiks, and security agents.

Gierek may have attempted to assert his influence during the 1968 Polish political crisis. Shortly after the student rally on March 8 in Warsaw, Gierek led a mass gathering of 100,000 party members from the entire province in Katowice on March 14. He was the first Politburo member to publicly address the ongoing protests. He later claimed his motivation was to demonstrate support for Gomułka's rule, which was being challenged by Mieczysław Moczar's internal party scheming. Gierek used strong language, condemning the alleged "enemies of People's Poland" who were "disturbing the peaceful Silesian water." He showered them with propaganda epithets and ominously alluded to their bones being crushed if they persisted in trying to deviate the "nation" from its "chosen course." Gierek was reportedly embarrassed when participants at the party conference in Warsaw on March 19 shouted his name alongside Gomułka's as an expression of support. The events of 1968 ultimately strengthened Gierek's position, particularly in the eyes of his Soviet patrons in Moscow.

3. First Secretary of the PZPR (1970-1980)

Edward Gierek's decade as Poland's de facto leader was marked by ambitious economic policies aimed at modernization and improving living standards, but these ultimately led to a crippling debt crisis and escalating social unrest.

3.1. Rise to Power and Initial Policies

When the 1970 Polish protests were violently suppressed, Edward Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as the First Secretary of the party, becoming the most powerful political figure in Poland. In late January 1971, he put his new authority to the test by personally traveling to Szczecin and Gdańsk to negotiate with the striking workers. One of his initial popular moves was to rescind the consumer price increases that had triggered the recent revolt. Additionally, Gierek made the significant decision to rebuild the Royal Castle in Warsaw, which had been destroyed during World War II and was not included in the post-war restoration of the city's Old Town. State-controlled media frequently highlighted his foreign upbringing and his fluency in French, presenting him as a more modern and accessible leader.

Gierek's ascension marked a definitive generational change within Poland's ruling communist elite, a process that had begun under Gomułka in 1968. Thousands of party activists, including important elder leaders from the pre-war Communist Party of Poland, were removed from positions of responsibility and replaced by individuals whose careers had started after World War II. Much of this extensive overhaul occurred during and after the VI Congress of the PZPR, convened in December 1971. The resulting governing class was notably one of the youngest in Europe. Under Gierek, the role of the administration expanded at the expense of the party, guided by the maxim "the party leads, the government governs." Throughout the 1970s, Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz was the most visible member of the top leadership after Gierek. From May 1971, Gierek's political rival, Mieczysław Moczar, was increasingly marginalized from power.

3.2. Economic Modernization and Western Engagement

Given that the riots leading to Gomułka's downfall were primarily rooted in economic hardship, Gierek promised extensive economic reform. He instituted an ambitious program aimed at modernizing Polish industry and increasing the availability of consumer goods. This "reform" was, however, based predominantly on securing large-scale foreign loans, rather than implementing fundamental systemic restructuring. The perceived need for deeper reforms was overshadowed by the investment boom the country experienced in the first half of the 1970s.

Gierek cultivated strong relationships with Western leaders, notably France's Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and West Germany's Helmut Schmidt, which facilitated Poland's access to foreign aid and significant loans. He is widely credited with opening Poland to greater political and economic influence from the West. He engaged in extensive foreign travel and hosted important international guests in Poland, including three presidents of the United States. Gierek also enjoyed a good relationship with Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, which allowed him to pursue his policies, including the globalization of Poland's economy, with minimal Soviet interference. Despite this, he readily granted the Soviets concessions that his predecessor, Gomułka, would have considered contrary to Poland's national interest.

Key modernization projects under Gierek included the opening of the first fully-operational highway in Poland, connecting Warsaw to Katowice in 1976. He also initiated the production of the Fiat 126 car in Poland, affectionately nicknamed maluchtinyPolish, which became a popular symbol of the era. Furthermore, he oversaw the construction of Warszawa Centralna railway station, which was considered the most modern European railway station at the time of its completion on December 5, 1975.

3.3. Social Changes and Living Standards

The first half of the 1970s saw a marked improvement in the standard of living across Poland, leading many to hail Gierek as a "miracle worker." Poles experienced an unprecedented ability to purchase desired consumer items, such as compact cars, and travel more freely to Western countries. There was also a perceived solution to the persistent housing supply problem, with over 1.8 M flats constructed during his tenure. Decades later, many Poles would fondly remember this period as the most prosperous in their lives. The early years of Gierek's rule were also characterized by a loosening of state censorship and a greater openness to new Western ideas, positioning Poland as one of the most liberal countries within the Eastern Bloc.

3.4. Economic Decline and Foreign Debt

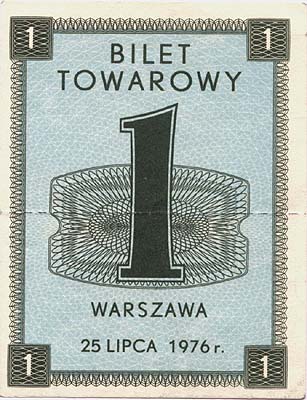

The economic prosperity of the early Gierek era, however, proved unsustainable. The Polish economy began to falter significantly following the 1973 oil crisis. By 1976, price increases became unavoidable, signaling the end of the "dynamic development" policy. The greatest accumulation of Poland's massive foreign debt occurred in the late 1970s, as the regime desperately struggled to counter the escalating effects of the economic crisis. Gierek's government ultimately proved unable to pay its creditors, leading to severe economic instability and shortages. As a consequence, rationing was introduced, symbolized by the "merchandise coupons" for sugar in August 1976, a system that remained in place until July 1989. The more than 24.00 B USD (in 1970s dollars) borrowed were, in hindsight, not well-spent, burdening Poland with a crippling debt that would last for decades.

3.5. Social Unrest and Rise of Opposition

The period of Gierek's rule is particularly notable for the emergence and growth of organized opposition movements in Poland. Significant controversy arose at the turn of 1975 and 1976 due to proposed amendments to the Constitution of the Polish People's Republic. These intended changes included formally recognizing the "socialist character of the state," the leading role of the PZPR, and the Polish-Soviet alliance. These widely opposed alterations prompted numerous protest letters and other acts of dissent, but they were nonetheless supported at the VII Congress of the PZPR in December 1975 and largely implemented by the Sejm in February 1976. Organized opposition circles gradually expanded, reaching an estimated 3,000-4,000 members by the end of the decade.

Due to the deteriorating economic situation, the authorities announced at the end of 1975 that the 1971 freeze on food prices would have to be lifted. Prime Minister Jaroszewicz pushed for the price increases, coupled with financial compensation schemes that favored higher-income brackets. This policy was ultimately adopted despite strong objections from the Soviet leadership. The increase, supported by Gierek, was formally announced by Jaroszewicz in the Sejm on June 24, 1976. The following day, strikes erupted across the country, with particularly severe disturbances, brutally suppressed by the police, occurring in Radom, at Warsaw's Ursus Factory, and in Płock. On June 26, Gierek resorted to a traditional party crisis-management tactic, ordering mass public gatherings in Polish cities to demonstrate popular support for the party and condemn the "troublemakers."

Following the June 1976 protests, a significant opposition group, the Workers' Defence Committee (KOR), commenced its activities in September with the explicit aim of providing assistance to the persecuted worker protest participants. Although other opposition organizations were also established between 1977 and 1979, the KOR proved to be of particular historical importance due to its sustained efforts and impact.

3.6. Relations with the Catholic Church and the Soviet Union

Early in his term, Gierek notably abandoned the regime's long-standing practice of sporadic confrontation with the Polish Catholic Church. Instead, he opted for a policy of cooperation, which effectively granted the Church and its leaders a privileged position throughout the remainder of communist rule in Poland. Under this approach, the Church significantly expanded its physical infrastructure. Moreover, it evolved into a crucial political third force, frequently mediating conflicts between the authorities and various opposition activists.

Gierek's relationship with the Soviet Union was carefully managed. He cultivated a trusted relationship with Leonid Brezhnev, which allowed him a degree of freedom to pursue his policies, including the globalization of Poland's economy, with less Soviet interference than his predecessors. However, Gierek was also willing to grant concessions to the Soviets that his predecessor, Władysław Gomułka, would have considered contrary to Polish national interests. This balancing act reflected the complex geopolitical realities of the Eastern Bloc during his tenure.

3.7. Papal Visit and Political Climate

A profoundly significant event during Gierek's rule was the first papal visit of Pope John Paul II (born Karol Wojtyła, a Pole) to Poland, which took place from June 2 to June 10, 1979. Poland's ruling communists reluctantly permitted the visit, despite explicit advice from the Soviet Union to deny it. Gierek, who had previously met Pope Paul VI at the Vatican, held discussions with Pope John Paul II during his visit to Poland. This visit had a profound and lasting impact on the political and social landscape of the country, invigorating Polish society and strengthening the sense of national and spiritual identity outside the Party's control.

4. Downfall

Despite being persuaded by his colleagues not to resign after the failure of his 1976 price increase policy, divisions within Gierek's leadership team intensified. One faction, led by Edward Babiuch and Piotr Jaroszewicz, sought to keep him in power, while another, led by Stanisław Kania and Wojciech Jaruzelski, was less invested in preserving his leadership.

In May 1980, in the aftermath of the Soviet-Afghan War and the subsequent Western boycott of the Soviet Union, Gierek facilitated a meeting between Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and Leonid Brezhnev in Warsaw. Similar to Władysław Gomułka a decade earlier, this apparent foreign policy success created an illusion of security for the Polish party leader in his statesman persona. However, the true political determinants were the rapidly deteriorating economic situation and the resultant labor unrest. In July, Gierek took his usual vacation in the Crimea, where he had his last conversation with his friend Brezhnev. He responded to Brezhnev's gloomy assessment of the situation in Poland, including the spiraling indebtedness, with optimistic predictions, possibly not fully grasping the severity of the country's, and his own, predicament.

High foreign debts, persistent food shortages, and an increasingly outdated industrial base necessitated another round of economic reforms. Once again, in the summer of 1980, these price increases triggered protests across the country, particularly in the Gdańsk Shipyard and Szczecin Shipyard. Unlike previous occasions, the regime made the critical decision not to resort to force to suppress the strikes. Through the Gdańsk Agreement and other accords reached with Polish workers, Gierek was compelled to concede their fundamental right to strike, leading to the historic birth of the Solidarity labor union.

Shortly thereafter, in early September 1980, the Central Committee's VI Plenum replaced Gierek as party First Secretary with Stanisław Kania, effectively removing him from power. A leader who had been popular and trusted in the early 1970s, Gierek departed amidst infamy and ridicule, largely deserted by most of his former collaborators. The VII Plenum in December 1980 held both Gierek and Jaroszewicz personally responsible for the country's dire situation and removed them from the Central Committee. In an unprecedented move, the extraordinary IX Congress of the PZPR, in July 1981, voted to expel Gierek and his close associates from the party, as delegates held them responsible for the Solidarity-related crisis in Poland, and First Secretary Kania was unable to prevent this action. The next First Secretary of the PZPR, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, introduced martial law on December 13, 1981. Gierek was interned for a year starting in December 1981. Unlike the internment faced by opposition activists, Gierek's internment status brought him no social respect; he ended his political career as the era's main pariah.

5. Later Life and Death

Throughout the 1980s, Edward Gierek remained politically marginalized. However, in the 1990s, as the social costs of Poland's economic transformation became apparent, many Poles began to feel nostalgic for the "good old days" of his rule, despite economists' reminders of the persistent debt that Poland continued to repay.

Gierek lived in his home region until his death on July 29, 2001, from pneumoconiosis in a hospital in Cieszyn, near the southern mountain resort of Ustroń, where he spent his final years. During his retirement, he published his memoirs, Przewana dekada and Replika, both in 1990. By the time of his death, his rule was viewed more favorably by many, and over 10,000 people attended his funeral. In 2004, a political party named the "Edward Gierek Economic Revival Movement" was founded by Polish voters who harbored nostalgia for the Polish People's Republic in the 1970s and Gierek's era. This party championed Gierek's economic policies and lauded him as a politically perfect individual.

Edward Gierek had two sons with his lifelong wife, Stanisława, née Jędrusik. One of their sons, Adam Gierek, later became a Member of the European Parliament.

6. Legacy and Assessment

Edward Gierek's leadership period evokes a divided assessment within Polish society, reflecting both fond memories of improved living standards and sharp criticism for the long-term economic consequences of his policies.

6.1. Positive Recollections and Nostalgia

Gierek's government is fondly remembered by some segments of the Polish population for the noticeable improvements in living standards enjoyed by Poles during the 1970s. This period is associated with increased availability of consumer goods and a sense of modernization. Uniquely among PZPR leaders, Gierek evinced clear signs of public nostalgia, particularly after his death. A July 2018 poll indicated that 45% of Poles assessed Gierek's legacy as largely positive, while only 22% judged him negatively.

A significant aspect of his rule, often highlighted positively, is his commitment to avoiding lethal force against striking workers. Upon becoming First Secretary in December 1970, Gierek reportedly vowed that people would not be shot in the streets under his watch. In 1976, security forces did intervene in strikes, but only after relinquishing their firearms. By 1980, they refrained from using force altogether, marking a notable shift in state response to protests compared to previous eras.

6.2. Criticisms and Economic Responsibility

Conversely, critics emphasize that the improvements in living standards during Gierek's tenure were made possible only through unwise and unsustainable policies heavily reliant on massive foreign loans. This approach, they argue, directly led to the severe economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s. In hindsight, the more than 24.00 B USD borrowed were not well-spent, burdening Poland with a crippling financial legacy that took decades to overcome. The economic mismanagement and the resulting accumulation of debt are central to the negative assessment of his rule.

6.3. Societal Transformation and Class Dynamics

Sociologist and left-wing politician Maciej Gdula posits that the social and cultural transformation in Poland during the 1970s was even more fundamental than the changes observed in the 1990s, following the political transition. He argued that the general idea of the relationship of forces in Polish society, characterized by an an alliance of political and emerging financial elites with the middle class at the expense of the working class, has remained consistent since the 1970s, with the "mass solidarity" period of 1980-81 being an exception.

Since Gierek's era, Polish society has been increasingly dominated by the cultural perceptions and norms of the then-emerging middle class. Concepts such as management, initiative, personality, and the individualistic maxim "get educated, work hard and get ahead in life," combined with an emphasis on orderliness, gradually replaced class consciousness and the socialist egalitarian concept. As a result, workers began to lose their symbolic status within society, eventually becoming a more marginalized stratum.

7. Decorations and Awards

Edward Gierek received numerous domestic and foreign honors throughout his career.

;Poland

| Ribbon | Award |

|---|---|

| Order of the Builders of People's Poland |

| Order of the Banner of Work (1st Class) |

| Cross of Merit (Gold Cross) |

| Partisan Cross |

| Medal for Long Marital Life |

;Foreign Awards

| Ribbon | Awarding Nation and Award |

|---|---|

| Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold |

| Cuba: Order of José Martí |

| France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour |

| Portugal: Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry |

| Yugoslavia: Great Star of the Order of the Yugoslav Star |

| USSR: Order of Lenin |

| USSR: Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" |

| USSR: Order of the October Revolution |

8. External links

- [http://culture.polishsite.us/articles/art42.html Edward Gierek, Polish Leader from Decade 1970-1980]