1. Overview

Diosdado Macapagal (Diosdado Pangan Macapagaldjosˈdado makapaˈɡalTagalog, September 28, 1910 - April 21, 1997) was a Filipino lawyer, poet, and politician who served as the 9th President of the Philippines from 1961 to 1965, and as the 5th Vice President of the Philippines from 1957 to 1961. He was also a member of the House of Representatives of the Philippines and later headed the 1970 Philippine Constitutional Convention. Known affectionately as "The Poor Boy From Lubao" due to his humble origins, Macapagal dedicated his political career to combating corruption and stimulating the Philippine economy. His administration introduced the country's first comprehensive land reform law, liberalized foreign exchange, and shifted the observance of Philippine Independence Day from July 4 to June 12, commemorating the declaration of independence from Spain in 1898. He is the father of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who later served as the 14th President of the Philippines. Despite facing a Congress dominated by the rival Nacionalista Party, Macapagal pursued policies aimed at economic development and social progress, striving to alleviate the plight of the common man and establish a dynamic foundation for future growth.

2. Early Life and Background

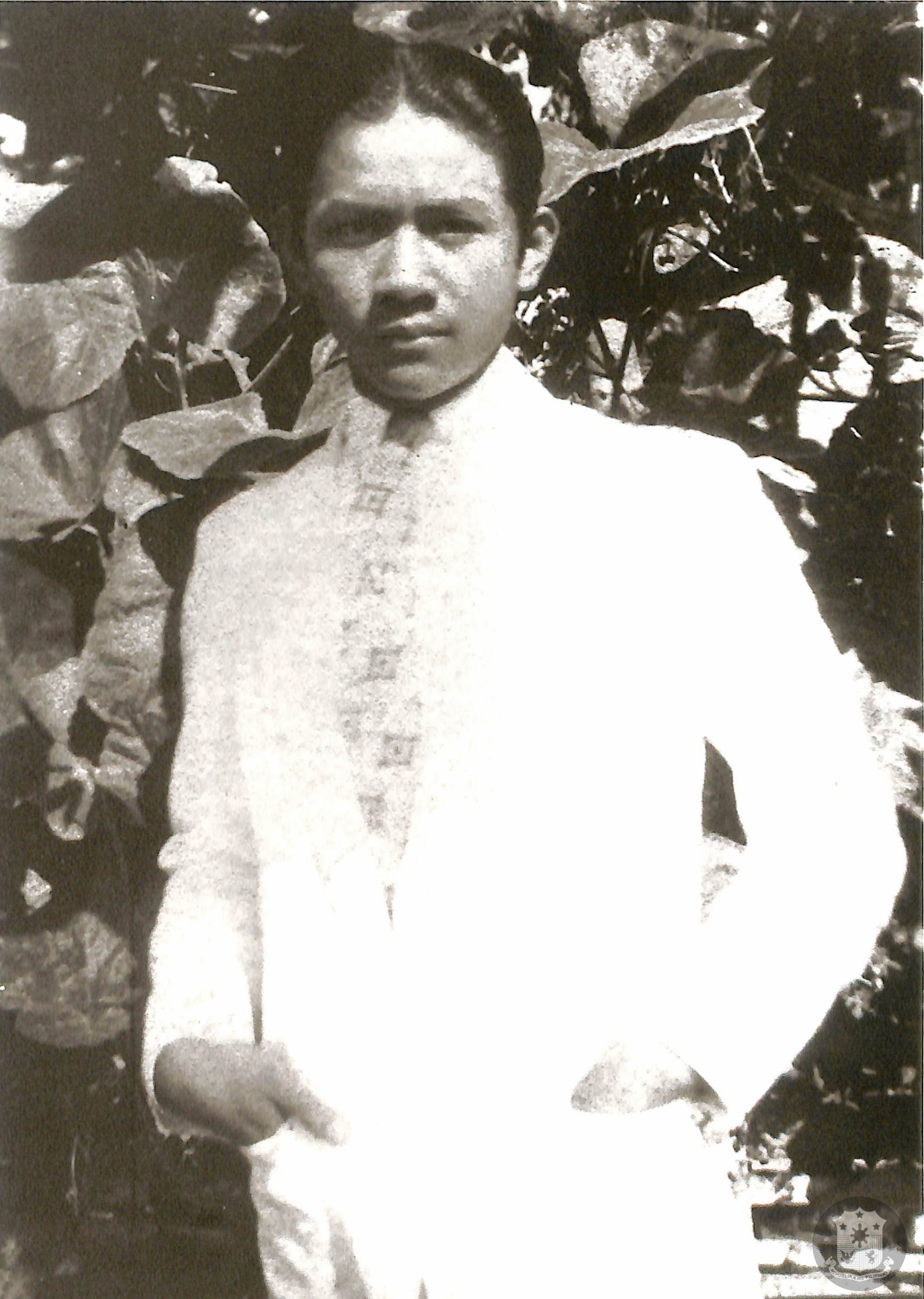

Diosdado Macapagal's early life was marked by humble beginnings and a strong emphasis on education, laying the foundation for his future political career.

2.1. Early Life and Family Environment

Diosdado Pangan Macapagal was born on September 28, 1910, in Barrio San Nicolas 1st, Lubao, Pampanga. He was the third of five children born into a poor family. His father, Urbano Romero Macapagal, was a poet who wrote in the local Pampangan language, and his mother, Romana Pangan Macapagal, was a schoolteacher who taught catechism. Romana was the daughter of Atanacio Miguel Pangan, a former cabeza de barangay of Gutad, Floridablanca, Pampanga, and Lorenza Suing Antiveros. His paternal grandmother, Escolástica Romero Macapagal, was a midwife and schoolteacher. The family supplemented their meager income by raising pigs and accommodating boarders in their home. Due to his impoverished roots, Macapagal would later become widely known as the "Poor Boy from Lubao". During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in World War II, his first wife died due to malnutrition, a stark reminder of the hardships of the era.

2.2. Ancestry and Lineage

Diosdado Macapagal was a distant descendant of Don Juan Macapagal, a prince of Tondo, who was a great-grandson of the last reigning lakan of Tondo, Lakan Dula. Through his mother, Romana, he was also related to the well-to-do Licad family; Romana was a second cousin of María Vitug Licad, the grandmother of renowned pianist Cecile Licad. Their shared ancestry traces back to sisters Genoveva Miguel Pangan and Celestina Miguel Macaspac, whose mother, María Concepción Lingad Miguel, was the daughter of José Pingul Lingad and Gregoria Malit Bartolo.

3. Education

Macapagal's academic journey was marked by exceptional intellectual achievements despite his family's financial constraints, demonstrating his dedication to scholarly pursuits.

3.1. Academic Achievements

Macapagal distinguished himself in his early studies. He graduated as valedictorian from Lubao Elementary School and as salutatorian from Pampanga High School. His academic excellence continued into higher education; he topped the 1936 bar examination with a score of 89.95%. While in law school, he gained prominence as an orator and debater.

3.2. Degrees and Scholarly Pursuits

After completing his pre-law course at the University of the Philippines Manila, Macapagal enrolled at Philippine Law School in 1932. He pursued his studies on a scholarship, supporting himself with a part-time job as an accountant. He was forced to temporarily halt his studies after two years due to poor health and financial difficulties. Upon returning to Pampanga, he raised enough money to continue his education at the University of Santo Tomas. He also received crucial financial assistance from philanthropist Don Honorio Ventura, who was then the Secretary of the Interior, and from his mother's relatives, particularly the Macaspacs, who owned significant landholdings in barrio Sta. Maria, Lubao, Pampanga.

He earned his Bachelor of Laws degree in 1936. Macapagal continued his graduate studies at the University of Santo Tomas, obtaining a Master of Laws degree in 1941, a Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1947, and a PhD in Economics in 1957. His doctoral dissertation was titled "Imperatives of Economic Development in the Philippines," reflecting his keen interest in national economic progress.

4. Early Career

Before entering national politics, Diosdado Macapagal built a solid foundation in legal practice and public service, demonstrating his commitment to the government and the nation.

4.1. Legal Practice

After successfully passing the bar examination, Macapagal was invited to join a prominent American law firm as a practicing attorney, an exceptional honor for a Filipino at that time. His legal acumen quickly led him to government service, where he was assigned as a legal assistant to President Manuel L. Quezon in Malacañang Palace. During the Japanese occupation of the Philippines in World War II, Macapagal continued his work in Malacañang Palace as an assistant to President José P. Laurel, while secretly contributing to the anti-Japanese resistance efforts during the Allied liberation of the country. Following the war, he worked as an assistant attorney with one of the country's largest law firms, Ross, Lawrence, Selph and Carrascoso.

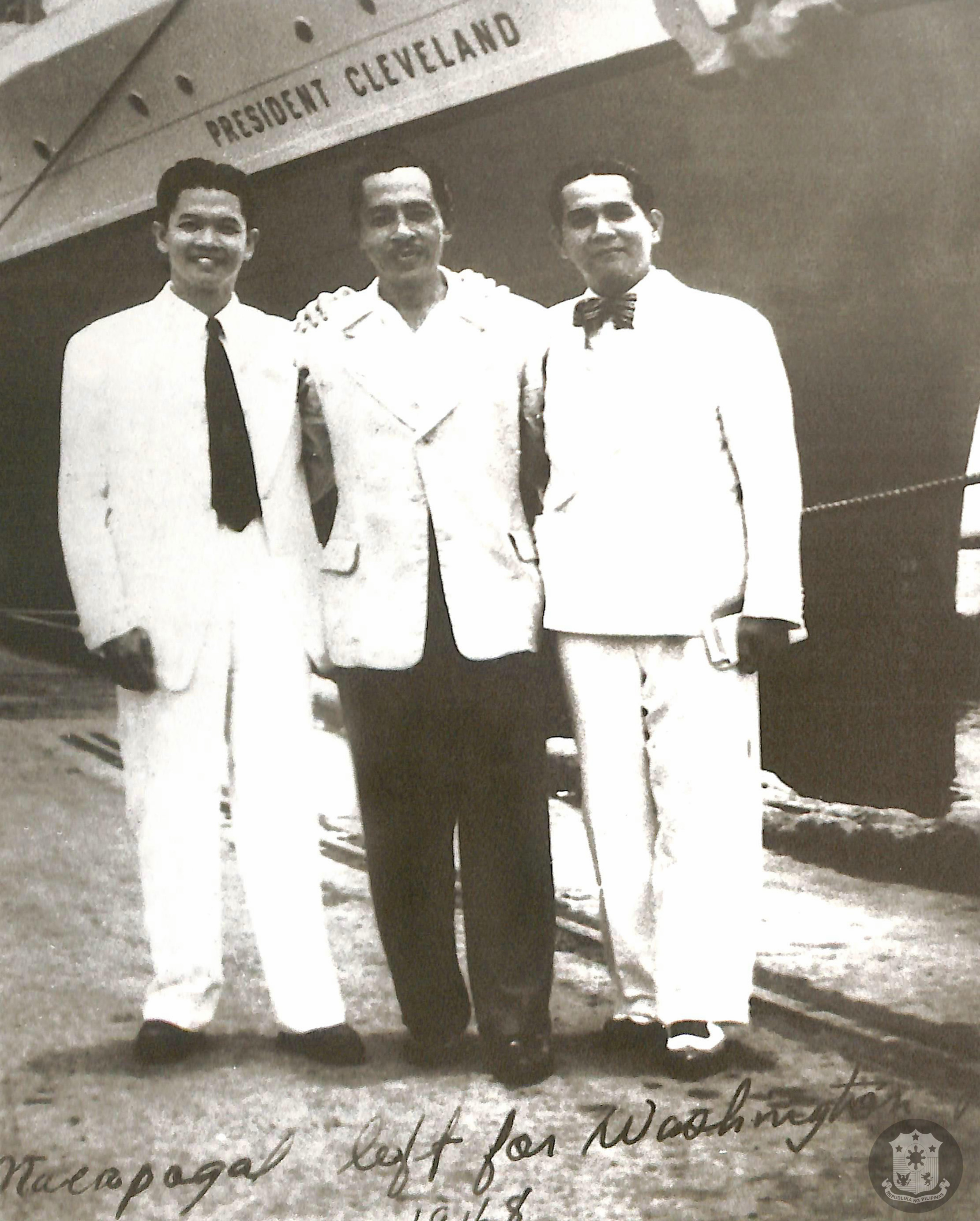

4.2. Public Service and Diplomatic Career

With the establishment of the independent Third Philippine Republic in 1946, Macapagal rejoined government service. President Manuel Roxas appointed him to the Department of Foreign Affairs as the head of its legal division. In 1948, President Elpidio Quirino appointed him as chief negotiator for the successful transfer of the Turtle Islands in the Sulu Sea from the United Kingdom to the Philippines. That same year, he was assigned as second secretary to the Philippine Embassy in Washington, D.C. By 1949, he had risen to the position of counselor on legal affairs and treaties, which was then the fourth-highest post in the Philippine Foreign Office.

Macapagal served multiple times as a Philippine delegate to the United Nations General Assembly, participating in significant debates on communist aggression with Soviet representatives like Andrei Vishinsky and Jacob Malik. He was also involved in crucial negotiations for the U.S.-R.P. Mutual Defense Treaty, the Laurel-Langley Agreement, and the Japanese Peace Treaty. He authored the Foreign Service Act, a landmark legislation that reorganized and strengthened the Philippine foreign service.

4.3. House of Representatives

At the urging of local political leaders in Pampanga province, President Quirino recalled Macapagal from his diplomatic post in Washington to run for a seat in the House of Representatives, representing the 1st district of Pampanga. Although the incumbent, Representative Amado Yuzon, was a friend, he was opposed by the administration due to his perceived support from communist groups. Macapagal won a landslide victory in the 1949 Philippine general election, following a campaign he described as cordial and free of personal attacks. He was re-elected in the 1953 Philippine general election, serving in the 2nd and 3rd Congress.

During his tenure, Macapagal was elected chair of the Committee on Foreign Affairs at the start of the 1950 legislative session, which led to several foreign assignments. As a representative, he authored and sponsored several laws of significant socio-economic importance, particularly those aimed at benefiting rural areas and the poor. Among the legislation he championed were the Minimum Wage Law, the Rural Health Law, the Rural Bank Law, the Law on Barrio Councils, the Barrio Industrialization Law, and a law nationalizing the rice and corn industries. His legislative contributions earned him consistent recognition from the Congressional Press Club as one of the Ten Outstanding Congressmen, and in his second term, he was named the most outstanding lawmaker of the 3rd Congress.

5. Vice Presidency (1957-1961)

Diosdado Macapagal's tenure as Vice President was unique, as he served as a prominent figure in the opposition, setting the stage for his presidential bid.

5.1. Liberal Party Leadership

In the May 1957 general elections, the Liberal Party nominated Congressman Macapagal to run for Vice President as the running-mate of José Yulo, a former Speaker of the House of Representatives. Macapagal's nomination was strongly supported by Liberal Party president Eugenio Pérez, who emphasized the importance of integrity and honesty in the party's vice presidential candidate. Although Yulo was defeated by Carlos P. Garcia of the Nacionalista Party, Macapagal secured an upset victory, defeating the Nacionalista candidate, José Laurel, Jr., by over eight percentage points. A month after the election, he was chosen as the president of the Liberal Party, solidifying his leadership within the party.

5.2. Role as Opposition Leader

Macapagal became the first Philippine Vice President to be elected from a rival party of the incumbent president. Consequently, he served his four-year vice presidential term as a leading figure of the opposition. Breaking from tradition, the ruling Nacionalista Party refused to grant him a Cabinet position in the Garcia administration. He was offered a Cabinet role only on the condition that he switch allegiance to the Nacionalista Party, an offer he declined. Instead, he embraced his role as a vocal critic of the administration's policies and performance, which allowed him to capitalize on the increasing unpopularity of the Garcia government. Assigned primarily to ceremonial duties as Vice President, Macapagal strategically used his time to make frequent trips to the countryside, familiarizing himself with voters and actively promoting the image and agenda of the Liberal Party.

6. Presidency (1961-1965)

Diosdado Macapagal's presidency was characterized by significant efforts to reform the economy, combat corruption, and redefine national identity, though many of his initiatives faced considerable political resistance.

6.1. Election and Inauguration

In the 1961 presidential election, Macapagal challenged President Garcia's re-election bid. He campaigned on a platform promising an end to corruption and appealed to the electorate as a "common man" from humble beginnings. He successfully defeated the incumbent president with a decisive margin of 55% to 45%. His inauguration as the 9th President of the Philippines took place on December 30, 1961, at the Quirino Grandstand in Manila. The oath of office was administered by the Chief Justice of the Philippines from the Supreme Court of the Philippines. The same Bible used by Macapagal for his oath was later used by his daughter, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, when she took her oaths as Vice President in 1998 and as President in 2004.

6.2. Administration and Cabinet

During his administration, Macapagal signed several major legislations aimed at national development and social welfare. These included:

- Republic Act No. 3512, which created a Fisheries Commission, defining its powers, duties, and functions.

- Republic Act No. 3518, establishing the Philippine Veterans' Bank.

- Republic Act No. 3844, known as the Agricultural Land Reform Code, which instituted land reforms, aimed at abolishing tenancy, and channeling capital into industry.

- Republic Act No. 4166, which officially changed the date of Philippine Independence Day from July 4 to June 12 and declared July 4 as Philippine Republic Day.

- Republic Act No. 4180, an amendment to the Minimum Wage Law (Republic Act Numbered Six Hundred Two), which raised the minimum wage for certain workers.

6.3. Domestic Policies

Macapagal's domestic policies focused on economic liberalization, agrarian reform, and an assertive anti-corruption drive, reflecting his commitment to improving the lives of ordinary Filipinos.

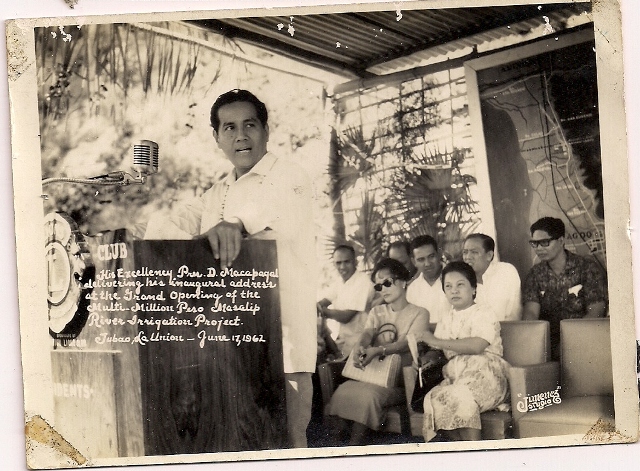

6.3.1. Economic Policies

In his inaugural address, President Macapagal outlined a socio-economic program rooted in a "return to free and private enterprise," advocating for economic development driven primarily by private entrepreneurs with minimal government intervention. Just twenty days after his inauguration, he implemented a significant economic reform by lifting exchange controls, which had been a temporary emergency measure since the administration of Elpidio Quirino but had been continued by subsequent presidents. This move allowed the Philippine peso to float freely on the currency exchange market. The peso, which had been fixed at 2.64 PHP to the U.S. dollar, subsequently devalued and stabilized at 3.8 PHP to the dollar, a stabilization supported by a 300.00 M USD fund from the International Monetary Fund. This policy, however, was noted to have drained millions of pesos from the national treasury annually during his term.

Macapagal firmly believed that free enterprise was the most suitable economic system for Filipinos, a view he had held since his eight years as a congressman. On January 21, 1962, after working for 20 continuous hours, he signed a Central Bank decree abolishing exchange controls and officially returning the country to a free enterprise system. During this crucial 20-day period between his inauguration and the opening of Congress, his main economic adviser was Andres Castillo, then governor of the Central Bank of the Philippines.

Despite his efforts, further reform initiatives by Macapagal were frequently obstructed by the Nacionalista Party, which held a dominant majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Nonetheless, Macapagal's administration achieved steady economic progress, with the annual GDP growth averaging 5.53% between 1962 and 1965. In 1962, the population was approximately 29.20 million. The Gross Domestic Product (at 1985 constant prices) was 234.83 B PHP in 1962 and 273.77 B PHP in 1965. Per capita income (at 1985 constant prices) was 8.04 K PHP in 1962 and 8.62 K PHP in 1965. Total exports amounted to 46.18 B PHP in 1962 and 66.22 B PHP in 1965. The exchange rate was 1 US dollar to 3.8 PHP, or 1 Philippine peso to 0.26 USD.

The removal of controls and the restoration of free enterprise were intended to create a fundamental environment for economic and social advancement. To guide both the private sector and the government, a specific and periodic program, formally known as the Five-Year Socio-Economic Integrated Development Program, was formulated under his direction by a group of economic and business leaders, notably Sixto Roxas III. This program aimed at three key objectives: the immediate restoration of economic stability, alleviating the plight of the common man, and establishing a dynamic basis for future growth.

Macapagal emphasized that while the success of his Socio-Economic Program in a free enterprise system inherently depended on the private sector, the government had a crucial role in providing active assistance. This role included providing social overhead such as roads, airfields, and ports that directly promote economic growth, adopting fiscal and monetary policies conducive to investments, and most importantly, serving as an entrepreneur or promoter of basic and key private industries, especially those requiring capital too large for private businessmen to undertake alone. Among the enterprises he selected for active government promotion were integrated steel, fertilizer, pulp, meat canning, and tourism.

6.3.2. Land Reform

President Diosdado Macapagal, who often referred to himself as the "Poor Boy from Lubao," championed agrarian reform. His most significant achievement in this area was the Agricultural Land Reform Code of 1963 (Republic Act No. 3844), a landmark legislation in the history of land reform in the Philippines. This code aimed to abolish the share-tenancy (kasama) system and provide for the purchase of private farmlands for distribution in small lots to landless tenants on easy payment terms.

Compared to previous agrarian legislation, the 1963 Code significantly lowered the retention limit for land ownership to 185 acre (75 ha), applicable to both individuals and corporations, and removed the term "contiguous" for land distribution. It formally established the leasehold system, prohibiting share-tenancy. The law also formulated a bill of rights for agricultural workers, ensuring their right to self-organization and a minimum wage. Furthermore, it created an office dedicated to acquiring and distributing farmlands and a financing institution to support this purpose.

However, the law had several critical flaws and exemptions that limited its effectiveness. Exemptions included large capital plantations established during the Spanish and American periods, fishponds, saltbeds, lands primarily planted to citrus, coconuts, cacao, coffee, durian, and other similar permanent trees, as well as landholdings converted to residential, commercial, industrial, or other non-agricultural purposes. The 185 acre (75 ha) retention limit was also considered too high given the growing population density. Moreover, the system of compensating landlords with bonds, which they could then use to purchase other agricultural lands, often resulted in merely transferring landlordism from one area to another rather than fundamentally altering the land ownership structure. Farmers were also given the option to be excluded from leasehold arrangements if they voluntarily surrendered their landholdings to the landlord.

Within two years of the law's implementation, very little land was purchased under its terms, primarily due to the peasants' inability to afford the land. The government also demonstrated a lack of strong political will, allocating only 1.00 M PHP for the code's implementation, a stark contrast to the estimated 200.00 M PHP needed within the first year and 300.00 M PHP over the next three years for the program to succeed. By 1972, the code had benefited only 4,500 peasants across 68 estates, at a cost of 57.00 M PHP to the government. Consequently, by the 1970s, farmers often ended up tilling less land, with their share in the farm also decreasing, leading to increased debts and dependence on landlords, creditors, and rice buyers. Indeed, during Macapagal's administration, the productivity of farmers further declined.

6.3.3. Anti-Corruption Drive

One of Macapagal's central campaign pledges was to eradicate the pervasive government corruption that had flourished under the previous Garcia administration. His administration actively pursued this goal, even openly feuding with influential Filipino businessmen Fernando Lopez and Eugenio Lopez, Sr., brothers who held controlling interests in several large businesses. The administration publicly alluded to the brothers as "Filipino Stonehills who build and maintain business empires through political power, including the corruption of politicians and other officials." This antagonism had political repercussions; in the 1965 Philippine general election, the Lopezes threw their support behind Macapagal's rival, Ferdinand Marcos, with Fernando Lopez serving as Marcos' running mate.

6.3.4. Stonehill controversy

The administration's campaign against corruption faced a significant test with the Harry Stonehill controversy. Harry Stonehill was an American expatriate who had built a 50.00 M USD business empire in the Philippines. Macapagal's Secretary of Justice, Jose W. Diokno, initiated an investigation into Stonehill on charges of tax evasion, smuggling, misdeclaration of imports, and corruption of public officials. Diokno's investigation uncovered extensive ties between Stonehill and corrupt elements within the government. However, Macapagal controversially intervened, preventing Diokno from prosecuting Stonehill by deporting the American instead, and subsequently dismissing Diokno from the cabinet. Diokno publicly questioned Macapagal's actions, stating, "How can the government now prosecute the corrupted when it has allowed the corrupter to go?" Diokno later went on to serve as a senator.

6.3.5. Independence Day Change

Macapagal appealed to nationalist sentiments by shifting the commemoration of Philippine Independence Day. On May 12, 1962, he signed a proclamation declaring Tuesday, June 12, 1962, as a special public holiday to commemorate the declaration of independence from Spain on that date in 1898. This change became permanent in 1964 with the signing of Republic Act No. 4166. Macapagal is generally credited with having officially moved the celebration date of the Independence Day holiday. Macapagal claimed that the decision to change Independence Day was not based on resentment towards the U.S., but rather as a legal decision about a previously established time. Years later, Macapagal confided to journalist Stanley Karnow a more pragmatic reason for the change: "When I was in the diplomatic corps, I noticed that nobody came to our receptions on the Fourth of July, but went to the American Embassy instead. So, to compete, I decided we needed a different holiday." During his term, Macapagal also formally recognized José P. Laurel, who had served as president during the Japanese occupation, as an official president of the Philippines, a status previously not acknowledged by post-war Philippine governments.

6.4. Foreign Policies

Macapagal's foreign policy initiatives sought to assert Philippine sovereignty, promote regional cooperation, and define the nation's stance amidst Cold War dynamics.

6.4.1. North Borneo Claim

On September 12, 1962, during President Diosdado Macapagal's administration, the territory of eastern North Borneo (now Sabah) was formally ceded to the Republic of the Philippines by the heirs of the Sultanate of Sulu, Sultan Muhammad Esmail E. Kiram I. This cession transferred full sovereignty, title, and dominion over the territory, effectively empowering the Philippine government to pursue its claim in international courts. The Philippines subsequently broke diplomatic relations with Malaysia after the federation incorporated Sabah in 1963.

However, the claim was effectively set aside in 1989 by succeeding Philippine administrations in the interest of fostering cordial economic and security relations with Kuala Lumpur. To date, Malaysia consistently rejects Philippine calls to resolve the matter of Sabah's jurisdiction through the International Court of Justice. From Malaysia's perspective, the claim made by Philippine Moro leader Nur Misuari to take Sabah to the ICJ is considered a non-issue and has been dismissed.

6.4.2. MAPHILINDO

In July 1963, President Diosdado Macapagal convened a summit meeting in Manila, where the concept of Maphilindo was proposed. This nonpolitical confederation for Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia was envisioned as a realization of José Rizal's dream of uniting the Malay peoples, who were seen as artificially divided by colonial frontiers.

Maphilindo was described as a regional association that would address issues of common concern through consensus. However, it was also widely perceived as a tactic by Jakarta and Manila to delay, or even prevent, the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. Manila had its own claim to Sabah (formerly British North Borneo), while Jakarta protested the formation of Malaysia as a British imperialist plot. The plan ultimately failed when Indonesian President Sukarno adopted his policy of "Konfrontasi" (Confrontation) with Malaysia. This policy, inspired by the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), aimed at preventing Malaysia from achieving independence, as the PKI convinced Sukarno that the formation of Malaysia was a form of neocolonialism that would destabilize Indonesia. The subsequent establishment and development of ASEAN effectively eliminated any possibility of the Maphilindo project ever being revived.

6.4.3. Vietnam War Stance

Before the end of his term in 1965, President Diosdado Macapagal sought to persuade the Philippine Congress to send troops to South Vietnam. This proposal, however, was blocked by the opposition, led by Senate President Ferdinand Marcos, who had defected from Macapagal's Liberal Party to the Nacionalista Party.

The U.S. government had actively pursued a policy of involving other nations in the Vietnam War as early as 1961. President Lyndon B. Johnson publicly appealed for other countries to aid South Vietnam on April 23, 1964, as part of what was termed the "More Flags" program. Chester Cooper, former director of Asian affairs for the White House, explained that the impetus for this campaign came from the United States rather than the Republic of South Vietnam itself, noting that the "More Flags" campaign "required the application of considerable pressure for Washington to elicit any meaningful commitments." He added that "one of the more exasperating aspects of the search...was the lassitude... of the Saigon government," which was preoccupied with political maneuvering and appeared to view the program primarily as a public relations effort directed at the American people. Macapagal's stance was part of his broader anti-communist foreign policy, which also saw him support the expansion of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).

6.5. 1963 Midterm Election

The senatorial election was held on November 12, 1963. Macapagal's Liberal Party (LP) won four out of the eight seats up for grabs during the election, thereby increasing the LP's Senate seats from eight to ten.

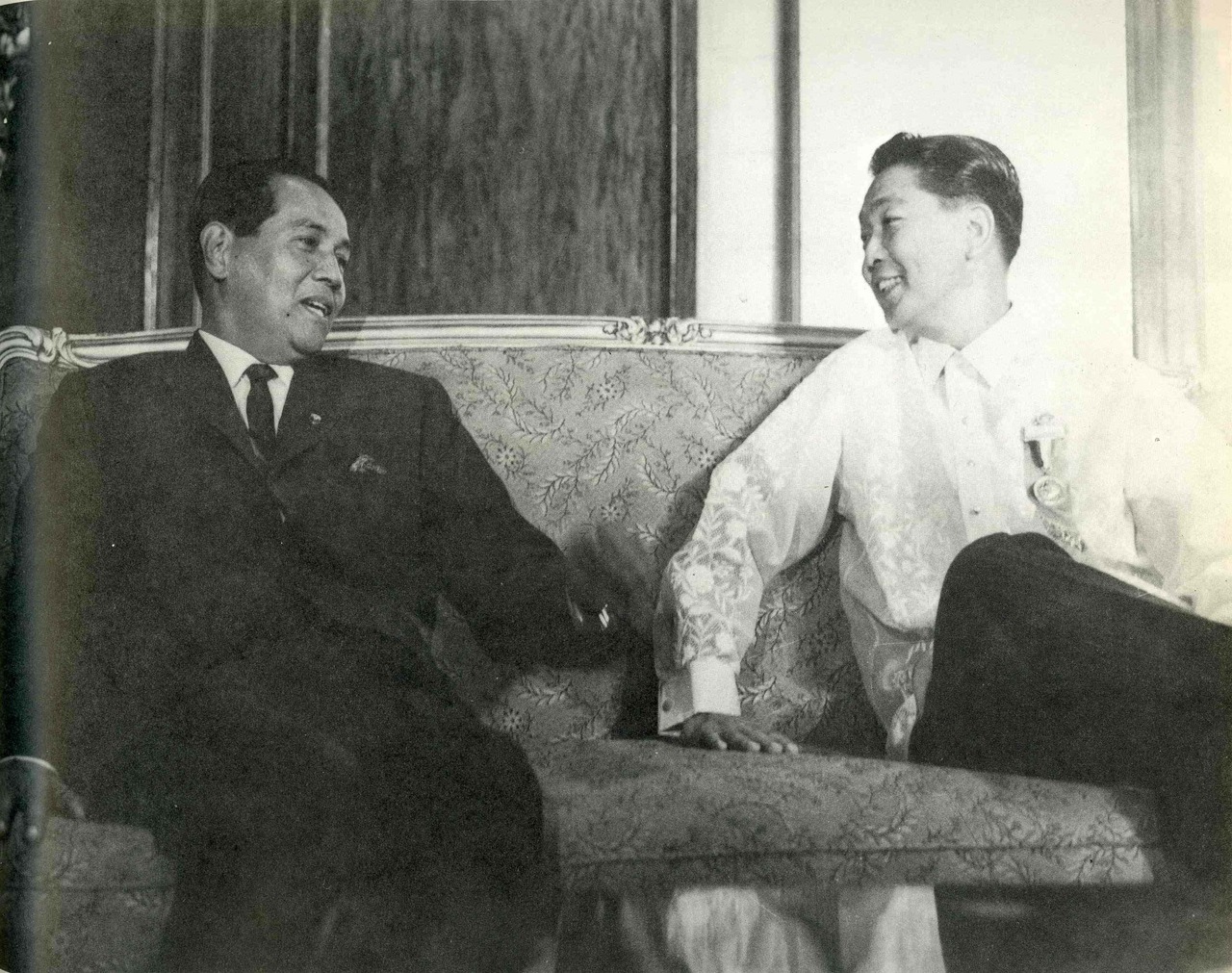

6.6. 1965 Presidential Campaign and Result

Towards the end of his term, Macapagal decided to seek re-election, believing it necessary to continue the reforms he claimed were being stifled by a "dominant and uncooperative opposition" in Congress. However, Senate President Ferdinand Marcos, a popular figure and fellow member of the Liberal Party, was unable to secure his party's nomination due to Macapagal's re-election bid. Consequently, Marcos switched his allegiance to the rival Nacionalista Party to oppose Macapagal in the upcoming election.

The campaign saw several issues raised against the incumbent administration, including allegations of graft and corruption, a rise in consumer goods prices, and persistent peace and order problems. In the November 1965 polls, Macapagal was defeated by Marcos, who secured 51.94% of the vote compared to Macapagal's 42.88%. This defeat marked the end of Macapagal's presidential term and ushered in the 21-year period of Marcos' rule, which would later become a dictatorship.

7. Post-Presidency

After leaving the presidency, Diosdado Macapagal remained a significant figure in Philippine politics, advocating for constitutional reform and opposing authoritarian rule, eventually assuming the role of an elder statesman.

7.1. Constitutional Convention

Following his loss in the 1965 election, Macapagal announced his retirement from active politics. However, in 1971, he was elected president of the constitutional convention tasked with drafting a new charter for the Philippines. This convention ultimately produced what became the 1973 Constitution. Despite his leadership in its drafting, the manner in which the charter was later ratified and modified under the Marcos regime led Macapagal to question its legitimacy.

7.2. Opposition to the Marcos Regime

As the Marcos administration consolidated power and moved towards authoritarian rule, Macapagal became an outspoken critic. In 1979, he formed the National Union for Liberation as a political party specifically to oppose the Marcos regime. During this period, he continued to voice his concerns about the erosion of democratic institutions, though his influence was not as widespread as it had been during his earlier political career.

7.3. Elder Statesman Role

Following the restoration of democracy in 1986, after the ousting of Ferdinand Marcos, Macapagal assumed the role of an elder statesman. He became a respected member of the Philippine Council of State and served as honorary chairman of the National Centennial Commission, as well as chairman of the board of CAP Life, among other positions. In his retirement, Macapagal dedicated much of his time to reading and writing. He published his presidential memoir, authored several books on government and economics, and contributed a weekly column to the Manila Bulletin newspaper.

Diosdado Macapagal died of heart failure, pneumonia, and renal complications at the Makati Medical Center on April 21, 1997, at the age of 86. He was accorded a state funeral and was interred at the Libingan ng mga Bayani on April 27, 1997.

8. Personal Life

Diosdado Macapagal's personal life included two marriages and a family that continued his legacy in Philippine politics.

8.1. First Marriage

In 1938, Macapagal married Purita de la Rosa. They had two children together: Cielo Macapagal-Salgado, who later became vice governor of Pampanga, and Arturo Macapagal. Purita de la Rosa passed away in 1943, during World War II, reportedly due to malnutrition. Jose Eduardo Diosdado Salgado Llanes is Macapagal's eldest great-grandson from this lineage.

8.2. Second Marriage and Children

On May 5, 1946, Macapagal married Dr. Evangelina Macaraeg. With Eva, he had two more children: Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, who would later follow in his footsteps to become the 14th President of the Philippines, and Diosdado Macapagal, Jr.

9. Achievements and Evaluation

Diosdado Macapagal's legacy is marked by his unwavering commitment to the common man, his pioneering economic reforms, and his contributions to Philippine national identity, despite the political challenges he faced.

9.1. National Commemoration

Diosdado Macapagal is widely commemorated in the Philippines. On September 28, 2009, his daughter, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, inaugurated the President Diosdado Macapagal Museum and Library in his hometown of Lubao, Pampanga. This institution houses his personal books and memorabilia. To mark the centennial of his birth, President Benigno S. Aquino III declared September 28, 2010, as a special non-working holiday in Macapagal's home province of Pampanga. His contributions are also recognized through various infrastructure projects and a monument in his honor.

His image is featured on the 200-peso note of both the New Design Series (issued from June 12, 2002, to 2013) and the New Generation Currency (issued from December 16, 2010, to present). Several infrastructure projects and landmarks have been named in his honor, including the Diosdado Macapagal International Airport in Clark, Pampanga (which was known by this name from 2003 to 2012), the Diosdado Macapagal Boulevard, and the Macapagal Bridge. A monument dedicated to him stands at the Pampanga Capitol.

9.2. Impact and Influence

Macapagal's presidency is often remembered for his fervent efforts to suppress graft and corruption and to stimulate the Philippine economy, earning him the moniker "The Incorruptible" or "Champion of the Common Man." His decision to lift exchange controls and float the peso was a bold move towards a free enterprise system, aiming to foster economic growth. The implementation of the Agricultural Land Reform Code of 1963, despite its limitations and the challenges of its execution, represented a significant attempt to address deep-seated agrarian issues and improve the lives of landless peasants. However, many of his proposed reforms were hampered by a Congress dominated by the rival Nacionalista Party, illustrating the political obstacles he faced.

His move to shift Independence Day from July 4 to June 12 was a powerful assertion of national identity, emphasizing the historical declaration of independence from Spain rather than the American grant of sovereignty. This act underscored his nationalist sentiments. In foreign policy, he sought to assert the Philippines' regional role through initiatives like MAPHILINDO, even though it ultimately failed due to regional geopolitical tensions. His attempt to send troops to South Vietnam, though blocked, highlighted his anti-communist stance during the Cold War. Despite his defeat in 1965, his post-presidency role as president of the 1971 Constitutional Convention and his subsequent opposition to the Marcos regime solidified his image as a defender of democratic principles. His emphasis on economic development, social progress, and democratic governance left a lasting, albeit often challenged, impact on Philippine society and political discourse.

10. Electoral History

Diosdado Macapagal's electoral career saw him contest and win key national positions.

| Election | Office | Result | Vote Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 Vice Presidential Election | Vice President | Won | 2,189,197 | 46.55% |

| 1961 Presidential Election | President | Won | 3,554,840 | 55.05% |

| 1965 Presidential Election | President | Lost | 3,187,752 | 42.88% |

11. Honors and Awards

Diosdado Macapagal received numerous national and international honors throughout his distinguished career.

11.1. National Commemoration

- Gawad Mabini: Grand Cross of the Gawad Mabini (GCrM) - (1994)

- Order of the Knights of Rizal: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Knights of Rizal (KGCR)

11.2. Foreign honors

- Republic of China: Grand Cordon of the Order of Brilliant Jade (May 2, 1960)

- Japan: Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum (1962)

- Spain: Knight of the Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (June 30, 1962)

- Italy: Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (July 1962)

- Vatican: Knight with Collar of the Order of Pius IX (July 9, 1962)

- Pakistan: Recipient of the Nishan-e-Pakistan (July 11, 1962)

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Collar of the Order pro merito Melitensi

- Thailand: Knight of the Order of the Rajamitrabhorn (July 9, 1963)

- West Germany: Grand Cross Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (November 1963)

12. Publications

Diosdado Macapagal was a prolific writer, authoring several books and articles on governance, economics, and his political experiences.

- Speeches of President Diosdado Macapagal. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1961.

- New Hope for the Common Man: Speeches and Statements of President Diosdado Macapagal. Manila: Malacañang Press Office, 1962.

- Five Year Integrated Socio-economic Program for the Philippines. Manila: [s.n.], 1963.

- Fullness of Freedom: Speeches and Statements of President Diosdado Macapagal. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1965.

- An Asian looks at South America. Quezon City: Mac Publishing House, 1966.

- The Philippines Turns East. Quezon City: Mac Publishing House, 1966.

- A Stone for the Edifice: Memoirs of a President. Quezon City: Mac Publishing House, 1968.

- A New Constitution for the Philippines. Quezon City: Mac Publishing House, 1970.

- Democracy in the Philippines. Manila: [s.n.], 1976.

- Constitutional Democracy in the World. Manila: Santo Tomas University Press, 1993.

- From Nipa Hut to Presidential Palace: Autobiography of President Diosdado P. Macapagal. Quezon City: Philippine Academy for Continuing Education and Research, 2002.

13. See also

- History of the Philippines (1946-1965)

- History of the Philippines

- Gloria Macapagal Arroyo

- Agricultural Land Reform Code

- MAPHILINDO

- Diosdado Macapagal Boulevard

- Macapagal Bridge