1. Overview

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a prominent Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his pioneering voyages in 1642 and 1644 on behalf of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Born in Lutjegast, Netherlands, in 1603, Tasman became a skilled navigator and was the first known European to reach the islands of Tasmania (originally named Van Diemen's Land) and New Zealand, as well as sight the Fiji Islands in 1643. His expeditions significantly expanded European knowledge of the Southern Pacific, leading to the first detailed mapping of extensive parts of Australia, New Zealand, and various Pacific Islands.

Despite his significant geographical discoveries, Tasman's voyages were often deemed commercially unsuccessful by the VOC, as he did not establish new profitable trade routes or relations with indigenous populations. Notably, his first contact with the Māori people in New Zealand resulted in a violent confrontation. Tasman continued to serve the VOC in various administrative and diplomatic roles in Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) until his death in 1659, leaving a lasting legacy in global geography, cartography, and exploration history, with numerous places and features named in his honor.

2. Early Life and Background

Abel Tasman's formative years and initial career laid the groundwork for his pivotal role in global exploration, developing his navigational expertise and connecting him with the powerful Dutch East India Company.

2.1. Origins and Early Career

Abel Tasman was born around 1603 in Lutjegast, a small village located in the province of Groningen in the northern Netherlands. The earliest available record mentioning him dates to December 27, 1631, when, at the age of 28, he was living in Amsterdam as a seafarer and became engaged to Jannetje Tjaers, aged 21, from the Palmstraat in the Jordaan district of the city. After being widowed, Tasman briefly resided in Amsterdam before his second marriage.

2.2. Service with the Dutch East India Company

In 1633, Tasman began his employment with the Dutch East India Company (VOC), sailing from Texel in the Netherlands to Batavia, which is now Jakarta, Indonesia. He utilized the southern Brouwer Route for this journey. While stationed in Batavia, Tasman participated in several early voyages that further honed his navigational and command skills.

One notable expedition took him to Seram Island in what is now the Maluku Province of Indonesia. This mission was initiated because local inhabitants were engaging in spice trade with other European nationalities, bypassing the Dutch. During an incautious landing on Seram, Tasman narrowly escaped death, while several of his companions were killed by the island's inhabitants.

By August 1637, Tasman had returned to Amsterdam. The following year, he signed another ten-year contract with the VOC and returned to Batavia, accompanied by his wife. In March 1638, he attempted to sell his property in the Jordaan district, though the purchase was later cancelled.

In 1639, Tasman served as second-in-command of an expedition into the North Pacific, led by Matthijs Quast. This fleet, which included the ships Engel and Gracht, was dispatched to search for two fabled islands rich in gold and silver, rumored to exist east of Japan. During this voyage, the expedition reached Fort Zeelandia in Dutch Formosa and Dejima, an artificial island off Nagasaki, Japan. They explored as far north as the southern tip of Hokkaido and east towards the International Date Line. Tasman and his crew were the first Europeans to sight Chichi-jima and Haha-jima of the Ogasawara Islands on July 21. Additionally, in 1642, he undertook a voyage to Palembang in southern Sumatra, where he successfully established friendly trade relations with the local sultan.

3. First Major Voyage (1642-1643)

Tasman's first major expedition represented a significant leap in European exploration, leading to the discovery of lands previously unknown to the Western world and marking the initial, often fraught, encounters with indigenous populations.

3.1. Objectives and Preparation

In August 1642, the Council of the Indies in Batavia, comprising Governor-General Anthony van Diemen and other prominent figures like Cornelis van der Lijn, Joan Maetsuycker, Justus Schouten, Salomon Sweers, Cornelis Witsen, and Pieter Boreel, commissioned Tasman and Franchoijs Jacobszoon Visscher to undertake a voyage of exploration. The expedition's primary objectives included gathering knowledge of "all the totally unknown" lands, particularly the fabled Provinces of Beach. This non-existent landmass, believed to be rich in gold, had appeared on European maps since the 15th century due to an error in some editions of Marco Polo's writings. The VOC also sought to discover new trade routes and establish commercial relations with native inhabitants. For this ambitious journey, Tasman's expedition utilized two small ships: the Heemskerck and the Zeehaen.

3.2. Voyage to Mauritius

Tasman departed from Batavia on August 14, 1642, following the directions provided by Visscher. The expedition arrived at Mauritius on September 5, 1642. This stopover was strategically chosen because the island offered abundant resources for the crew, including fresh water and timber for ship repairs, and provided a place for rest and resupply. Governor Adriaan van der Stel provided assistance to Tasman's crew during their stay.

Due to the prevailing winds, Mauritius served as a crucial turning point for their eastward journey. After a four-week stay on the island, both ships set sail on October 8, utilizing the powerful Roaring Forties to make rapid progress eastward. No previous Dutch voyage had ventured as far as Pieter Nuyts's expedition in 1626-1627. By November 7, severe weather, including snow and hail, influenced the ship's council to alter course to a more north-easterly direction, with the Solomon Islands as their revised destination.

3.3. Discovery of Tasmania

On November 24, 1642, Tasman's expedition sighted the west coast of Tasmania, specifically north of Macquarie Harbour. He named this newly discovered land "Van Diemen's Land" in honor of Anthony van Diemen, the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, who had commissioned his voyage.

Proceeding southward, Tasman's ships skirted the southern tip of Tasmania before turning northeast. He attempted to guide his two ships into Adventure Bay on the east coast of South Bruny Island but was forced back out to sea by a storm, an area he subsequently named Storm Bay. Two days later, on December 1, Tasman anchored his ships just north of Cape Frederick Hendrick, which is north of the Forestier Peninsula. On December 2, two ship's boats, commanded by Pilot Major Visscher, rowed through the Marion Narrows into Blackman Bay and then further west to the outflow of Boomer Creek, where they collected some edible "greens". Tasman named the larger area, encompassing present-day North Bay, Marion Bay, and what is now Blackman Bay, as Frederick Hendrik Bay. Tasman's original naming, Frederick Henrick Bay, was mistakenly transferred to its present location by Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne in 1772.

The following day, an attempt was made to land in North Bay. However, the sea was too rough, so a ship's carpenter bravely swam through the surf to shore and planted the Dutch flag. On December 3, 1642, Tasman formally claimed possession of the land for the Netherlands. For two more days, he continued to follow the east coast northward to ascertain its extent. When the coastline veered to the northwest at Eddystone Point, he tried to follow it, but his ships were abruptly hit by the powerful Roaring Forties winds howling through Bass Strait. As Tasman's mission was to locate the hypothetical Southern Continent, not more islands, he abruptly changed course to the east and continued his continent-seeking journey.

3.4. Discovery of New Zealand

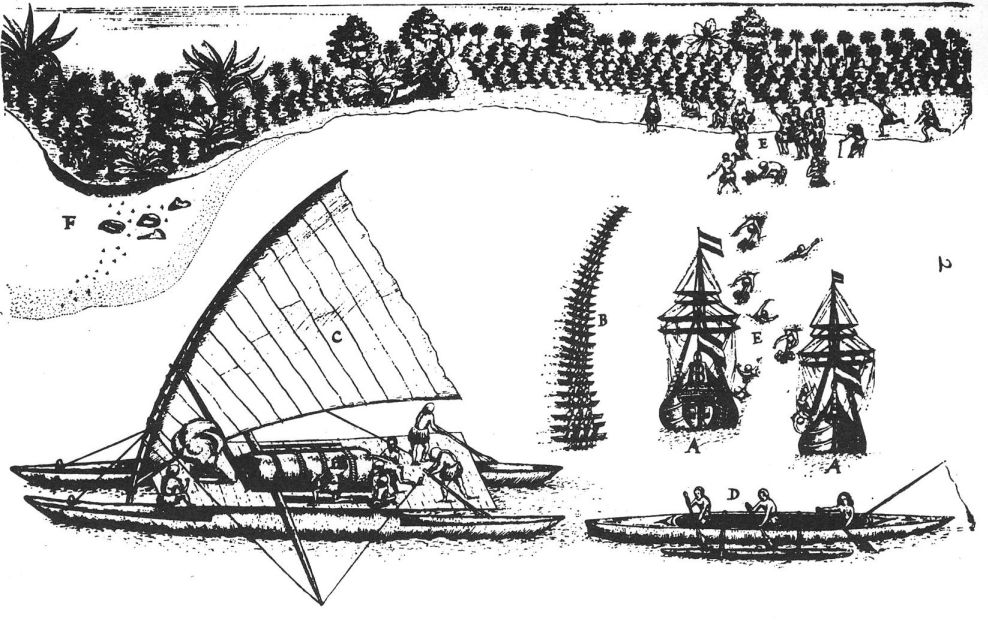

Tasman had initially intended to proceed in a northerly direction, but unfavorable winds compelled him to steer east. The expedition endured a challenging voyage, with Tasman noting in his diary that his compass was the only thing that kept him alive. On December 13, 1642, Tasman and his crew became the first Europeans to reach New Zealand when they sighted the northwest coast of the South Island. Tasman named this land Staten Landt (meaning "States' Land") "in honour of the States General" (the Dutch parliament). He recorded his belief that "it is possible that this land joins to the Staten Landt but it is uncertain," referring to Isla de los Estados (Staten Island), a landmass at the southern tip of South America discovered by Dutch navigator Jacob Le Maire in 1616. Tasman also believed he had found the western side of the long-imagined Terra Australis (Southern Land) that supposedly stretched across the Pacific. However, in 1643, Hendrik Brouwer's Dutch expedition to Valdivia discovered that Isla de los Estados was separated by sea from the hypothetical Southern Land, disproving Tasman's theory. Tasman maintained, "We believe that this is the mainland coast of the unknown Southland." On December 14, 1642, Tasman's ships anchored about 4.3 mile (7 km) offshore, approximately 12 mile (20 km) south of Cape Foulwind near Greymouth. The ships were observed by Māori, who named a place on this coast Tiropahi, meaning "the place where a large sailing ship was seen."

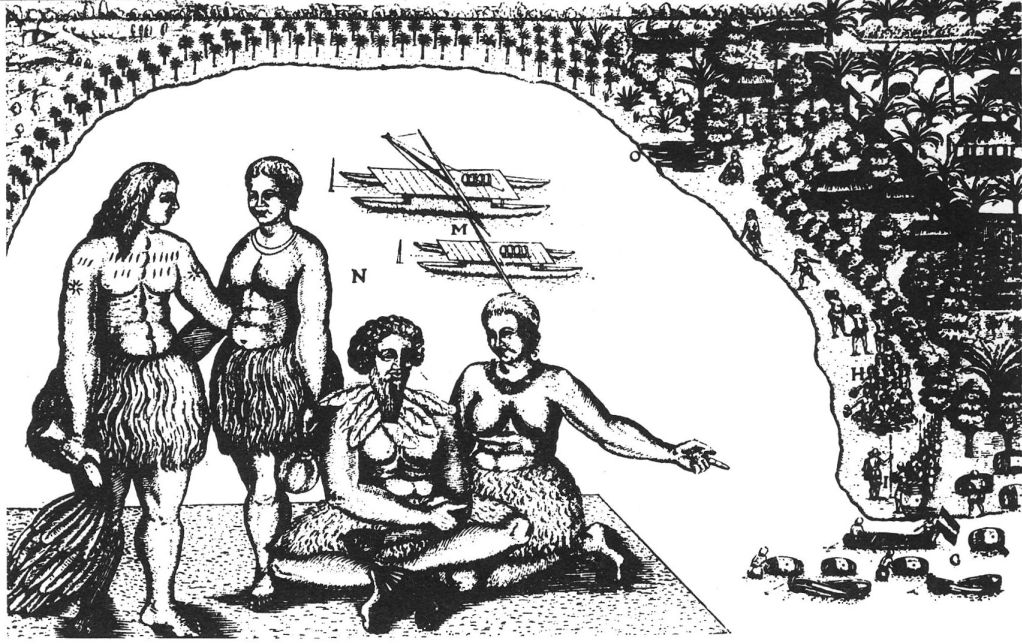

3.5. Encounter with Māori Peoples

After sailing north and then east for five days, the expedition anchored about 4.3 mile (7 km) from the coast off what is now Golden Bay. This marked the first documented European contact with the Māori people. A group of Māori paddled out in their waka (canoes) and attacked some sailors who were rowing between the two Dutch vessels. The confrontation resulted in the deaths of four of Tasman's sailors, who were clubbed to death with patu.

According to Tasman's journal, in the evening, approximately one hour after sunset, the crew observed many lights on land and four vessels near the shore, two of which approached the Dutch ships. After Tasman's boats returned to the ships, reporting a depth of no less than thirteen fathoms, and as the sun set, they were still about half a mile from shore. The people in the two canoes began calling out in "gruff, hollow voices," which the Dutch could not understand. When the Māori called out again, the Dutch responded with their own calls. The Māori did not come closer than a stone's throw and repeatedly blew an instrument that produced a sound similar to "moors' trumpets." One of Tasman's sailors, who could play the trumpet, played some tunes in response.

As Tasman sailed out of the bay, he observed 22 waka near the shore, with "eleven swarming with people coming off towards us." The waka approached the Zeehaen, which fired, hitting a man in the largest waka, who was holding a small white flag. Canister shot also struck the side of a waka. Archaeologist Ian Barber suggests that the local Māori were attempting to secure a cultivation field under ritual protection (tapu), believing the Dutch were trying to land there. December was the midpoint of the locally important sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) growing season. In the aftermath of this violent encounter, Tasman named the area "Murderers' Bay," which is now known as Golden Bay.

The expedition then sailed north, sighting Cook Strait, which separates the North and South Islands of New Zealand. Tasman and his crew mistakenly identified it as a bight and named it "Zeehaen's Bight." Two geographical names given by the expedition in the far north of New Zealand remain to this day: Cape Maria van Diemen and the Three Kings Islands. However, Kaap Pieter Boreels was later renamed Cape Egmont by Captain James Cook 125 years later. Tasman's belief that New Zealand was part of a larger Southern Continent significantly influenced European cartography for the next century, until Cook's circumnavigation of New Zealand disproved it in 1769.

3.6. Exploration of Tonga and Fiji

En route back to Batavia, Tasman's expedition came across the Tongan archipelago on January 20, 1643. While passing the Fiji group, Tasman's ships narrowly avoided being wrecked on the dangerous reefs located in the northeastern part of the archipelago. He meticulously charted the eastern tip of Vanua Levu and the island of Cikobia-i-Lau before successfully navigating his way back into the open sea.

3.7. Return and Initial Assessment

Following their exploration of Tonga and Fiji, the expedition turned northwest towards New Guinea. Tasman and his crew successfully arrived back in Batavia on June 15, 1643.

From the perspective of the Dutch East India Company, Tasman's first expedition was a disappointment. Although he had made groundbreaking geographical discoveries, he had neither found a promising area for trade nor established any useful new shipping routes or significant contact with the native inhabitants. Despite these unmet commercial objectives, Tasman's expedition undeniably paved the way for further European exploration and eventual colonization of Australia and New Zealand, particularly by the British, a century later.

4. Second Major Voyage (1644)

Tasman's second major voyage in 1644 focused on filling cartographical gaps and further exploring the northern reaches of the Southern Continent, though it also failed to meet the commercial expectations of the Dutch East India Company.

4.1. Route and Mapping of Northern Australia

Abel Tasman embarked on his second voyage from Batavia on January 30, 1644. This expedition consisted of three ships: the Limmen, the Zeemeeuw, and the tender Braek. Tasman's primary objective was to thoroughly map parts of New Holland (the historical Dutch name for continental Australia) and to locate a passage to its eastern side.

He initially followed the south coast of New Guinea eastward, attempting to find a strait that would lead him through to the other side. However, Tasman missed the Torres Strait, the narrow passage between New Guinea and Australia. This oversight was likely due to the numerous reefs and islands that obscured potential routes in the area, making navigation particularly challenging. Instead of finding the strait, Tasman continued his voyage westward, meticulously following the shore of the Gulf of Carpentaria along the northern Australian coast. During this journey, he comprehensively mapped the northern coastline of Australia, making important observations regarding New Holland and its indigenous inhabitants. He arrived back in Batavia in August 1644.

4.2. VOC Evaluation and Consequences

From the perspective of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Tasman's second expedition, much like his first, proved to be a disappointment. He had failed to discover either a promising area for trade or a commercially useful new shipping route, which were the VOC's main priorities. Despite being received courteously upon his return, the company was dissatisfied that Tasman had not more thoroughly explored the lands he had found. Consequently, the VOC decided that any future expeditions should be led by a "more persistent explorer" who would fully investigate discovered territories. For over a century following Tasman's voyages, until the era of James Cook, Tasmania and New Zealand remained largely unvisited by Europeans. While mainland Australia saw occasional European visits, these were often accidental rather than part of deliberate exploratory efforts.

5. Later Life and Career

After his major voyages, Tasman continued his service with the Dutch East India Company, taking on various administrative and diplomatic roles in Batavia, navigating both official duties and personal challenges.

5.1. Life in Batavia and Administrative Roles

On November 2, 1644, shortly after his second major voyage, Abel Tasman was appointed as a member of the Council of Justice in Batavia. This marked a shift in his career towards administrative duties within the VOC's colonial administration. His responsibilities included diplomatic missions; in 1646, he traveled to Sumatra, and in August 1647, he journeyed to Siam (modern-day Thailand) to deliver official letters from the company to the King.

In May 1648, Tasman was put in charge of an expedition dispatched to Manila with the objective of intercepting and looting Spanish silver ships arriving from America. However, this mission proved unsuccessful, and he returned to Batavia in January 1649 without having achieved his goal.

5.2. Legal Proceedings and Reinstatement

In November 1649, Abel Tasman faced legal challenges. He was formally charged and subsequently found guilty of having executed one of his men in the previous year without a proper trial. As a consequence of this conviction, he was suspended from his office as commander, fined, and ordered to pay compensation to the relatives of the deceased sailor. Despite this significant setback, Tasman's standing within the VOC was eventually restored. On January 5, 1651, he was formally reinstated to his rank.

5.3. Final Years and Death

Following his reinstatement, Abel Tasman spent his remaining years in Batavia. He lived in comfortable circumstances, having become one of the larger landowners in the town. Tasman died in Batavia on October 10, 1659. He was survived by his second wife and a daughter from his first marriage. In his will, drafted in 1657, he bequeathed 25 NLG to the poor of his birth village, Lutjegast. While his detailed journal from the 1642 voyage was not published until 1898, some of his charts and maps were circulated and utilized by subsequent explorers. The original journal of the 1642 voyage, signed by Abel Tasman, is preserved in the Dutch National Archives at The Hague.

6. Legacy and Impact

Abel Tasman's explorations, though initially deemed commercially disappointing by his sponsors, fundamentally reshaped European understanding of global geography and left an indelible mark on cartography and the naming of regions across the Southern Hemisphere.

6.1. Geographical and Cartographical Contributions

Tasman's ten-month voyage in 1642-1643 had profound and lasting consequences for global geography. By effectively circumnavigating Australia, albeit at a distance, Tasman provided crucial evidence that the landmass, then referred to as New Holland, was not connected to any larger sixth continent, specifically disproving the long-imagined Southern Continent, or Terra Australis.

Furthermore, Tasman's observation that New Zealand might be the western side of this hypothetical Southern Continent influenced many European cartographers for the next century. Maps from this period often depicted New Zealand as part of a Terra Australis extending gradually from the waters near Tierra del Fuego. This theory was ultimately disproved by Captain James Cook when he circumnavigated New Zealand in 1769. Although Tasman's detailed journal was not published until 1898, some of his charts and maps were widely circulated, providing invaluable information for subsequent explorers and significantly advancing European knowledge of the Pacific.

6.2. Places and Features Named After Tasman

Abel Tasman's enduring legacy is reflected in the numerous geographical locations, features, and entities named in his honor. These include:

- The Australian island and state of Tasmania, which was renamed after him, having previously been known as Van Diemen's Land. Features within Tasmania bearing his name include:

- The Tasman Peninsula

- The Tasman Bridge

- The Tasman Highway

- The Tasman Sea, which lies between Australia and New Zealand.

- In New Zealand:

- The Tasman Glacier

- Tasman Lake

- The Tasman River

- Mount Tasman

- The Abel Tasman National Park

- Tasman Bay

- The Tasman District

- The Abel Tasman Monument

- Other entities named after him include:

- Tasman Pulp and Paper company, a major producer in Kawerau, New Zealand.

- Abel Tasman Drive, located in Tākaka, New Zealand.

- The former passenger and vehicle ferry, Abel Tasman.

- The Able Tasmans, an indie band from Auckland, New Zealand.

- Tasman, a layout engine developed for Internet Explorer.

- 6594 Tasman (1987 MM1), a main-belt asteroid.

- Tasman Drive in San Jose, California, and its associated Tasman light rail station, both named after the Tasman Sea.

- Tasman Road in Claremont, Cape Town, South Africa.

- HMNZS Tasman, a shore-based training establishment of the Royal New Zealand Navy.

- HMAS Tasman, a Hunter-class frigate expected to enter service with the Royal Australian Navy in the late 2020s.

6.3. Cultural Depictions and Recognition

Abel Tasman's life and voyages have been commemorated and depicted in various forms of art and cultural recognition. His portrait has appeared on four New Zealand postage stamp issues and on a 1992 5 NZD coin. He was also featured on Australian postage stamps issued in 1963, 1966, and 1985. In the Netherlands, numerous streets are named after him, and his birth village of Lutjegast hosts a museum dedicated to his life and travels. In 1946, his life was dramatized in the radio play Early in the Morning by Ruth Park.

6.3.1. Portraits and depictions

A drawing titled Abel Janssen Tasman, Navigateur en Australie is held by the State Library of New South Wales as part of a portfolio containing 26 ink drawings of 16th and 17th-century Dutch admirals, navigators, and governor-generals of the VOC. This portfolio was acquired at an art auction in The Hague in 1862. However, it remains uncertain whether the drawing truly depicts Tasman, and its original source is unknown, though it has been noted to resemble the work of Dutch engraver Jacobus Houbraken. Despite these uncertainties, the drawing has been assessed as having the "most reliable provenance" among Tasman's depictions, with "no strong reason to doubt that the drawing is not genuine."

In 1948, the National Library of Australia acquired a portrait from Rex Nan Kivell purporting to depict Tasman with his wife and stepdaughter. This painting was attributed to Jacob Gerritsz. Cuyp and dated to 1637. In 2018, the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands exhibited this painting, identifying it as "the only known portrait of the explorer." However, the Netherlands Institute for Art History has since attributed the painting to Dirck van Santvoort and concluded that it does not, in fact, depict Tasman and his family. The provenance provided by Nan Kivell for this family portrait has been impossible to verify. Nan Kivell claimed the portrait was passed down through the Springer family-relatives of Tasman's widow-and was sold at Christie's in 1877. However, Christie's records indicate that the portrait was neither owned by the Springer family nor associated with Tasman; it was instead sold as "Portrait of an astronomer" by "Anthonie Palamedes" (sic). Nan Kivell also claimed a second sale at Christie's in 1941, but no records exist to support this. A 2019 survey of Tasman's portraits concluded that the provenance was "either invented by Rex Nan Kivell or by the unnamed art dealer who sold it to Rex Nan Kivell," and therefore, the painting "should not be considered a portrait of Abel Tasman's family."

Beyond the Nan Kivell painting, another purported portrait of Tasman was "discovered" in 1893 and eventually acquired by the Tasmanian government in 1976 for the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG). This painting is unsigned and was attributed to Bartholomeus van der Helst at the time of its discovery, an attribution disputed by Dutch art historian Cornelis Hofstede de Groot and Alec Martin of Christie's. In 1985, TMAG curator Dan Gregg stated that "the painter of the life-sized portrait is unknown [...] there is some uncertainty as to whether the portrait is really of Tasman."

6.4. Historical Evaluation and Social Consequences

Tasman's discoveries are fundamentally significant in the history of European colonial expansion. His voyages provided crucial cartographical information that helped outline the Australian continent and established the existence of New Zealand and Tasmania. However, the immediate commercial disinterest from the VOC meant that his extensive geographical knowledge was not fully leveraged for over a century, contributing to a delayed and different trajectory for European settlement in these regions compared to other parts of the world.

From the perspective of indigenous populations, Tasman's expeditions represent the initial, and often violent, encounters with European explorers. The confrontation with the Māori at "Murderers' Bay" underscores the clash of cultures and competing claims to land and resources. While Tasman himself did not establish colonies, his charting of these lands inevitably set the stage for future European incursions and the profound social consequences that followed, including the eventual displacement and subjugation of indigenous peoples.

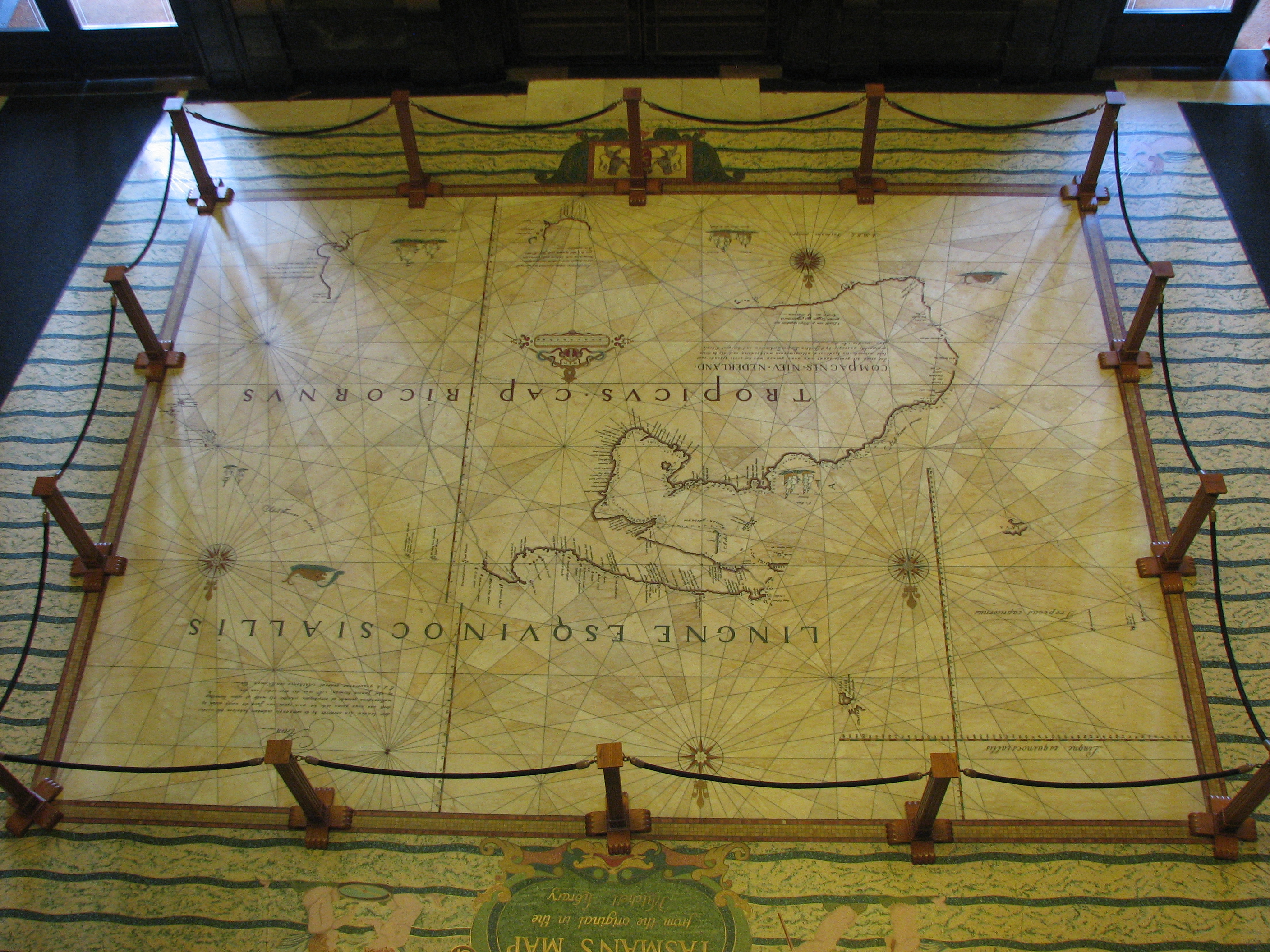

The Tasman map, also known as the Bonaparte map, is a crucial artifact reflecting the extent of Dutch understanding of the Australian continent during Tasman's era. Held within the collection of the State Library of New South Wales, it is believed to have been drawn by Isaack Gilsemans or completed under the supervision of Franz Jacobszoon Visscher. The map, completed sometime after 1644, integrates information from Tasman's first and second voyages. As no journals or logs from Tasman's second voyage have survived, the Bonaparte map remains an invaluable contemporary record of his exploration of the northern Australian coast.

The map illustrates the western and southern coasts of Australia, which were accidentally encountered by Dutch voyagers en route from the Cape of Good Hope to Batavia. It meticulously details the tracks of Tasman's two voyages, including the Banda Islands, the southern coast of New Guinea, and much of northern Australia from his second expedition. Notably, the land areas adjacent to the Torres Strait are depicted as unexamined, despite Tasman having received explicit orders from the VOC Council at Batavia to investigate the possibility of a channel between New Guinea and the Australian continent.

There is ongoing debate regarding the map's origin, with some believing it was produced in Batavia and others in Amsterdam. Its authorship is also contested; while commonly attributed to Tasman, it is now thought to be a collaborative effort, likely involving Franchoijs Visscher and Isaack Gilsemans, both of whom participated in Tasman's voyages. The exact completion date of the map is also debated, as a VOC company report from December 1644 suggested that no maps illustrating Tasman's voyages were fully completed at that time. In 1943, a mosaic version of the map, crafted from colored brass and marble, was inlaid into the vestibule floor of the Mitchell Library in Sydney. This work was commissioned by Principal Librarian William Herbert Ifould and executed by the Melocco Brothers of Annandale.

7. Personal Life

Abel Tasman's personal life provides some context to his broader career. After his first wife passed away, he resided in Amsterdam before marrying Jannetje Tjaers in 1631. He later brought his second wife with him to Batavia in 1638 when he signed a new ten-year contract with the VOC. Upon his death in 1659, Tasman was survived by his second wife and a daughter from his first marriage. His property was divided between them according to his will.