1. Early Life and Background

René Goscinny's early life was marked by his family's immigrant background and a childhood spent in Argentina, where he developed an early interest in drawing and humor.

1.1. Birth and Family

René Goscinny was born on August 14, 1926, at 42 Rue Fer-à-Moulin in Paris, France. His parents were Jewish immigrants from Poland. His father, Stanisław Simkha Gościnny, was a chemical engineer from Warsaw, while his mother, Anna (Hanna) Bereśniak-Gościnna, hailed from Chodorków (modern-day Khodorkiv), a small village near Kyiv in Ukraine. The surname Gościnny is common in Poland and means "hospitable." Goscinny's maternal grandfather, Abraham Lazare Berezniak, founded a printing company. His older brother, Claude, was born on December 10, 1920, making him six years René's senior. Stanisław and Anna had met and married in Paris in 1919.

1.2. Childhood and Education

When René was two years old, in 1928, the Gościnny family relocated to Buenos Aires, Argentina, following his father's new appointment as a chemical engineer there. René experienced a happy childhood in Buenos Aires, where he attended French-language schools. Despite a natural shyness, he often played the role of the "class clown" to compensate. From a very young age, he showed an inclination for drawing, inspired by the illustrated stories he enjoyed reading.

1.3. Early Career and Military Service

In December 1943, the year after Goscinny graduated from high school, his father died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. This unforeseen tragedy compelled the 17-year-old Goscinny to seek employment. The following year, he secured his first job as an assistant accountant in a tire recovery factory. After being laid off a year later, he transitioned to a junior illustrator position at an advertising agency.

In 1945, Goscinny and his mother emigrated from Argentina to New York City, United States, to join his uncle, Boris. To avoid service in the United States Armed Forces, he traveled to France in 1946 to join the French Army. He served briefly at Aubagne in the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion. During his service, he was promoted to senior corporal and became the regiment's appointed artist, creating illustrations and posters for the army. After completing his military service, he returned to New York in April 1947.

2. Career Start and Major Collaborations

Goscinny's return to New York marked a challenging period, but it led to crucial encounters that shaped his career. His eventual move back to France solidified his professional path and initiated his most celebrated collaborations.

2.1. New York Period and Early Works

Upon his return to New York, Goscinny faced a difficult period, struggling with joblessness and poverty for a while, partly due to his limited English proficiency. By 1948, his fortunes began to change when he found work in a small studio. Here, he forged friendships with future contributors to MAD Magazine, including Will Elder, Jack Davis, and Harvey Kurtzman. Kurtzman, in particular, offered Goscinny various illustration opportunities and introduced him to other influential artists. Goscinny also became an art director at Kunen Publishers, where he authored four children's books.

During this time, he met two prominent Belgian comic artists: Jijé (Joseph Gillain) and Morris (Maurice de Bevere). Morris, who resided in the U.S. for six years, had already launched his renowned Western comic series, Lucky Luke. Goscinny and Morris began their collaboration on Lucky Luke in 1955, with Goscinny writing the scripts until his death in 1977. This period is widely regarded as the series' "golden age."

2.2. Return to France and Key Collaborations

In 1951, Georges Troisfontaines, the head of the World Press agency in Brussels, invited Goscinny to return to France to lead their Paris office. Goscinny accepted, settling in Paris. In 1952, while working at the World Press Paris branch, he met Albert Uderzo, a young cartoonist from Normandy. This meeting marked the beginning of a long and highly fruitful collaboration between the two artists.

Their initial joint projects included work for Bonnes Soirées, a women's magazine for which Goscinny wrote Sylvie. They also launched the series Jehan Pistolet and Luc Junior in La Libre Junior magazine. In 1955, Goscinny, alongside Uderzo, Jean-Michel Charlier, and Jean Hébrad, co-founded the syndicate Edipress/Edifrance. This syndicate published various works, including Clairon for factory unions and Pistolin for a chocolate company. Goscinny and Uderzo continued their partnership on series such as Bill Blanchart in Jeannot, Pistolet in Pistolin, and Benjamin et Benjamine in the magazine of the same name.

Under the pseudonym Agostini, Goscinny began writing Le Petit Nicolas for illustrator Jean-Jacques Sempé. This series first appeared in Le Moustique magazine, later being republished in Sud-Ouest and Pilote magazines.

In 1956, Goscinny commenced a significant collaboration with Tintin magazine, where his scriptwriting talent helped the publication regain its prominence. He wrote numerous short stories for artists like Jo Angenot and Albert Weinberg. His work for Tintin also included Signor Spaghetti with Dino Attanasio, Monsieur Tric with Bob de Moor, Prudence Petitpas with Maurice Maréchal, Globul le Martien and Alphonse with Tibet, Strapontin with Berck, and Modeste et Pompon with André Franquin. An early creation with Uderzo, Oumpah-pah, was also adapted for serial publication in Tintin from 1958 to 1962. Additionally, Goscinny contributed to magazines like Paris-Flirt (Lili Manequin with Will) and Vaillant (Boniface et Anatole with Jordom, Pipsi with Godard).

3. Major Works and Creative Activities

René Goscinny's creative output was prolific and diverse, encompassing the creation of iconic comic series and a pivotal role in the French comic publishing industry.

3.1. Founding of Pilote Magazine and the Creation of Asterix

In 1959, the Édifrance/Édipresse syndicate, co-founded by Goscinny, launched the new Franco-Belgian comics magazine Pilote. Goscinny quickly became one of the magazine's most productive writers. In the very first issue of Pilote, he and Albert Uderzo debuted their most famous creation, Astérix. The series was an instant success and rapidly gained worldwide popularity.

The initial print run for the first Asterix album was 6 K copies. However, the second album, La Serpe d'or (Asterix and the Golden Sickle), sold over 20 K copies, and the third, Astérix et les Goths (Asterix and the Goths), exceeded 40 K copies in sales. The immense and sustained popularity of the Asterix series led to widespread media recognition; on September 19, 1966, L'Express magazine featured a cover story titled "The New French Hero, the Asterix Phenomenon."

Asterix has been translated into over 107 languages, including Latin, making it one of the most translated comic series globally. After Goscinny's death, Uderzo continued the series, and by 1996, over 260 M copies of the albums had been sold. The success of Asterix extended beyond comics, leading to numerous adaptations including animated films, live-action films, radio programs, and theatrical plays. In 1989, the Parc Astérix theme park was established in Plailly, France, becoming a renowned tourist attraction.

3.2. Other Notable Comic Series

Beyond Asterix, Goscinny was instrumental in the success of several other prominent comic series, collaborating with various artists:

- Lucky Luke: From 1955 until his death in 1977, Goscinny wrote the scripts for this popular Western comic, illustrated by Morris. This period is considered the "golden age" of the series.

- Le Petit Nicolas: Created with illustrator Jean-Jacques Sempé, this beloved children's series began in 1959 and ran until 1965.

- Iznogoud: Collaborating with Jean Tabary, Goscinny launched this satirical series in 1962. It initially appeared as Calife Haroun El Poussah in Record magazine before continuing in Pilote as Iznogoud.

- Les Dingodossiers: From 1965 to 1967, Goscinny worked on this humorous series with Marcel Gotlib.

- Other collaborations included Modeste et Pompon with André Franquin, Signor Spaghetti with Dino Attanasio, Prudence Petitpas with Maurice Maréchal, Oumpah-pah with Albert Uderzo, and Strapontin with Berck. He also contributed to series like Valentin le vagabond with Jean Tabary, Tromblon et Bottaclou with Godard, Les Divagations de Monsieur Sait-Tout with Martial, La Potachologie Illustrée with Cabu, La Forêt de Chênebeau with Mic Delinx, Pantoufle with Raymond Macherot, Alphonse with Tibet, and Monsieur Tric with Bob de Moor.

3.3. Editorial Role at Pilote

In 1960, the magazine Pilote was acquired by Georges Dargaud. Following this acquisition, René Goscinny assumed the role of editor-in-chief, a position he held from 1963 to 1974. In this capacity, he oversaw the publication's development and continued to be a highly productive writer for the magazine, launching new series and fostering creative talent.

4. Animation and Film Production

In the 1970s, Goscinny expanded his creative endeavors into the animation and film industry, seeking greater control over the adaptations of his popular works.

4.1. Studios Idéfix and Film Projects

Goscinny and Uderzo, along with Morris and their publisher Georges Dargaud, were often dissatisfied with the animated adaptations of their works produced by other studios, such as Belvision Studios in Brussels, Belgium. Albert Uderzo stated, "Goscinny and I were very unhappy watching the previous films... we had to go through the premieres several times... they had become enormous! For this one, we can avoid this kind of thing. Goscinny and I are doing the storyboarding and we hope to oversee everything. Because this time the cartoon will be produced in Paris, by a studio that we created ourselves. We will be both authors and directors, we will work really closely with the animators. If we're embarking on this adventure, it's because we've pulled out all the stops!"

This motivation led them to establish their own animation studio, Studios Idéfix, on April 1, 1974. René Goscinny described this venture as the "culmination of ten years of work," a "childhood dream" realized thanks to the success of Asterix. The studio's logo, designed by Uderzo, was a parody of MGM's famous logo, featuring Dogmatix (known in French as Idéfix) in place of Leo and a banner reading "Delirant Isti Romanii" (Latin for "These Romans are crazy!").

Launching an animation feature film studio in France at the time was complex, especially after the closure of Les Gémeaux in 1952, which had faced financial ruin. To build the technical and artistic teams for Studios Idéfix, Goscinny enlisted Henri Gruel, who had previously directed animated short films and was responsible for the sound effects of earlier Asterix animated features. Gruel also convinced Goscinny to share the artistic direction with Pierre Watrin, a talented designer and former animator of Paul Grimault. The search for experienced animators proved challenging, as many former employees of Les Gémeaux had transitioned into illustration and advertising. At Goscinny's request, Gruel sent Serge Caillet to the Paris Chamber of Commerce and Industry to advocate for the establishment of an animated cinema section, aiming to provide a steady supply of young artists to the studios.

Studios Idéfix ultimately produced two feature films:

- The Twelve Tasks of Asterix (1976): This was the studio's first self-produced film, created in collaboration with Halas and Batchelor and Dargaud. Goscinny served as co-director, co-writer, and co-producer for this film.

- La Ballade des Dalton (The Ballad of the Daltons) (1978): This Lucky Luke feature was the studio's second and final production. Goscinny contributed as a producer and voiced Jolly Jumper, Lucky Luke's horse, in what became his final film role.

The studio ceased operations and closed permanently on April 1, 1978, following Goscinny's sudden death in 1977, which occurred during the production of The Ballad of the Daltons.

Goscinny's involvement in film and television also included:

- Tous les enfants du monde (1964): Scenario for a short film.

- Tintin et les Oranges bleues (1964): Adaptation for a film.

- Astérix le Gaulois (1967): Original story for an animated film.

- Deux Romains en Gaule (1967): Original story and scenario for a TV film.

- Astérix et Cléopâtre (1968): Original story for an animated film; he also provided an uncredited voice for the commentator.

- Daisy Town (1971): Production for an animated film.

- Le Viager (1972): Scenario for a film.

- Les Gaspards (1974): Scenario for a film.

- Minichroniques (1976): Director for a TV series.

5. Personal Life

René Goscinny married Gilberte Pollaro-Millo in 1967. The following year, in 1968, their daughter, Anne Goscinny, was born. Anne later followed in her father's footsteps and became an author. In 2022, she co-wrote the screenplay for the animated film Little Nicholas: Happy As Can Be, based on her father's famous character.

6. Death and Legacy

René Goscinny's untimely death sent shockwaves through the comic world, but his legacy endures through his vast body of work and continued recognition.

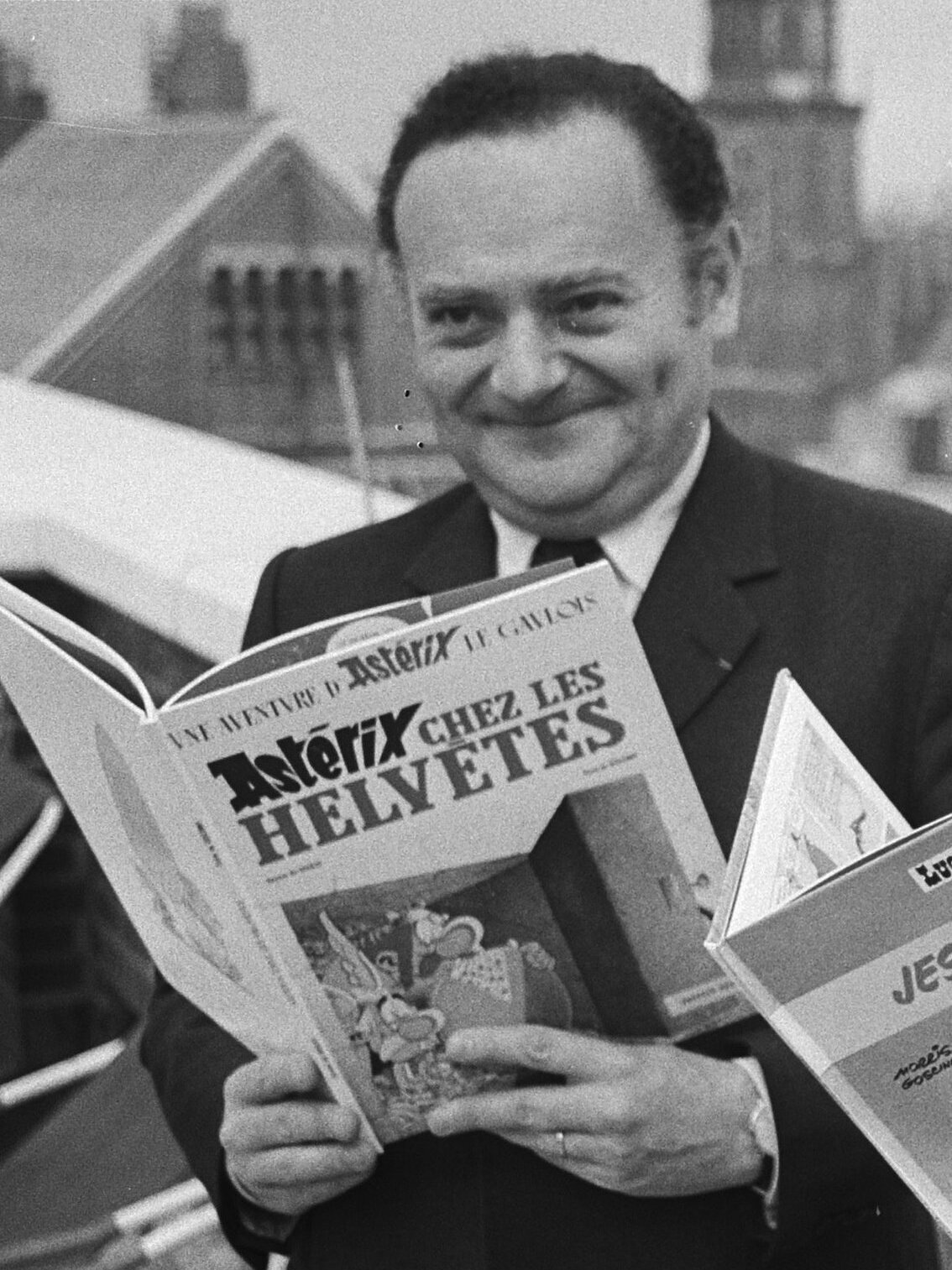

6.1. Death and Tributes

René Goscinny died at the age of 51 in Paris on November 5, 1977. He suffered a heart attack during a routine cardiac stress test at his doctor's office on Chazelles street. He was buried in the Jewish Cemetery in Nice. In accordance with his will, the majority of his estate was transferred to the Chief Rabbinate of France.

Goscinny's death occurred midway through the writing of Asterix in Belgium, which was eventually published in 1979, two years after his passing. As a poignant homage to his late colleague, Albert Uderzo incorporated darkened skies and rain into the comic's artwork. Specifically, the last panel on page 32 and all but the last panel on page 33 were drawn with grey skies and rain to mark the exact point at which Goscinny died. Most of the remaining panels in the book also featured leaden grey skies, though without rain. A further tribute appears in the final panel of the book, where Uderzo drew a rabbit sadly looking over its shoulder towards Goscinny's signature, a subtle nod to his friend.

After Goscinny's death, Uderzo took on the writing duties for Asterix himself, continuing the series, albeit at a much slower pace, until he passed the creative reins to writer Jean-Yves Ferri and illustrator Didier Conrad in 2011. Similarly, Jean Tabary continued writing Iznogoud, while Morris continued Lucky Luke with various other writers. As another tribute, Uderzo gave his late colleague's likeness to the Jewish character Saul ben Ephishul in the 1981 album L'Odyssée d'Astérix (Asterix and the Black Gold), which was dedicated to Goscinny's memory.

French media reacted strongly to his death. Bruno Frappat of Le Monde stated on November 8, 1977, that "René Goscinny was to comics what the Eiffel Tower is to Paris, Balzac to French literature, and Obelix's word to Asterix." Hergé, the creator of Tintin, remarked in Le Matin on November 7, 1977, "Tintin bowed before Asterix."

6.2. Awards and Honors

René Goscinny received numerous awards and honors throughout his lifetime and posthumously, recognizing his immense talent and influence:

- 1964: Awarded the Prix Alphonse Allais in France for his humorous work, specifically for the collection Le Petit Nicolas et les copains (Little Nicolas and the Friends).

- 1966: Received the Le Prix Alphonse Allais for his humorous works.

- 1967: Conferred the title of Chevalier des Arts et Lettres (Knight of Arts and Letters) by the French government. He also received the Ordre national du Mérite, one of France's highest state honors.

- 1974: Honored with the Adamson Award for best international comic strip artist in Sweden.

- 2005: Posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame as a Judges' choice in the United States.

Since 1996, the René Goscinny Award has been presented annually at the Angoulême International Comics Festival in France, serving as an encouragement for young comic writers.

6.3. Cultural Impact and Recognition

Goscinny's cultural impact is profound and global. His works have been extensively translated, making him one of the most translated authors in the world. According to UNESCO's Index Translationum, as of August 2017, Goscinny was the 20th most-translated author, with 2,200 translations of his work. Earlier figures from April 2008 placed him as the 22nd most-translated author with 1,800 translations. The Asterix series alone has been translated into over 107 languages, including Latin.

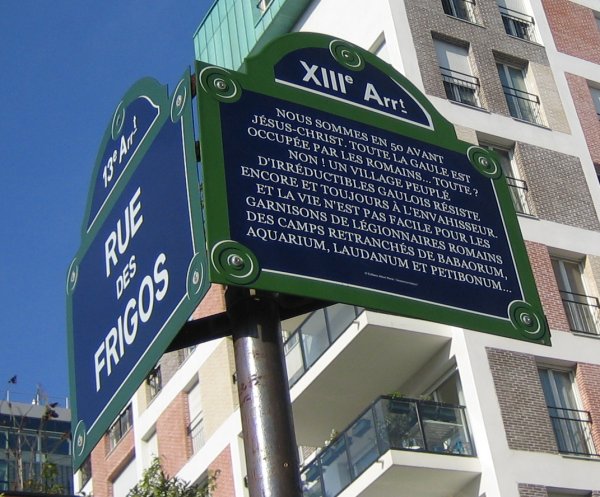

Public honors commemorating Goscinny include the naming of a street in Paris, Rue René-Goscinny, as well as numerous schools and libraries across France. On January 23, 2020, a life-sized bronze statue of Goscinny was unveiled near his former home in Paris, marking the first public statue in the city dedicated to a comic book author. The "Asterix phenomenon" he created expanded beyond comics into various cultural industries, including animated films, live-action movies, radio programs, theater, and even the establishment of the Parc Astérix theme park in 1989, which remains a popular tourist destination.

6.4. Influence on Later Generations

René Goscinny is widely regarded as a pioneer in comic scriptwriting. Before his emergence, the role of a dedicated comic scriptwriter was largely undefined in France; artists often wrote their own stories. Goscinny's innovative approach to storytelling, character development, and humor set a new standard for the medium. His beloved characters and the enduring appeal of his narratives continue to inspire generations of creators and readers, solidifying his status as a foundational figure in the history of comics.

7. Bibliography

| Series | Years | Magazine | Albums | Editor | Artist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lucky Luke | 1955-1977 | Spirou and Pilote | 38 | Dupuis and Dargaud | Morris |

| Modeste et Pompon | 1955-1958 | Tintin | 2 | Le Lombard | André Franquin |

| Prudence Petitpas | 1957-1959 | Tintin | Lombard | Maurice Maréchal | |

| Signor Spaghetti | 1957-1965 | Tintin | 15 | Lombard | Dino Attanasio |

| Oumpah-pah | 1958-1962 | Tintin | 3 | Lombard | Albert Uderzo |

| Strapontin | 1958-1964 | Tintin | 4 | Lombard | Berck |

| Astérix | 1959-1977 | Pilote | 24 | Dargaud | Albert Uderzo |

| Le Petit Nicolas | 1959-1965 | Pilote | 5 | Denoël | Sempé |

| Iznogoud | 1962-1977 | Record and Pilote | 14 | Dargaud | Jean Tabary |

| Les Dingodossiers | 1965-1967 | Pilote | 3 | Dargaud | Gotlib |

8. Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | Tous les enfants du monde | Scenario | Short film |

| 1964 | Tintin et les Oranges bleues | Adaptation | Film |

| 1967 | Astérix le Gaulois | Original story | Animated film |

| 1967 | Deux Romains en Gaule | Original story, Scenario | TV film |

| 1968 | Asterix and Cleopatra | Original story, Co-director | Animated film |

| 1971 | Daisy Town | Production | Animated film |

| 1972 | Le Viager | Scenario | Film |

| 1974 | Les Gaspards | Scenario | Film |

| 1976 | The Twelve Tasks of Asterix | Production, Co-director, Co-writer, Co-producer | Animated film |

| 1976 | Minichroniques | Director | TV series |

| 1978 | La Ballade des Dalton | Production, Voice (Jolly Jumper) | Animated film |