1. Overview

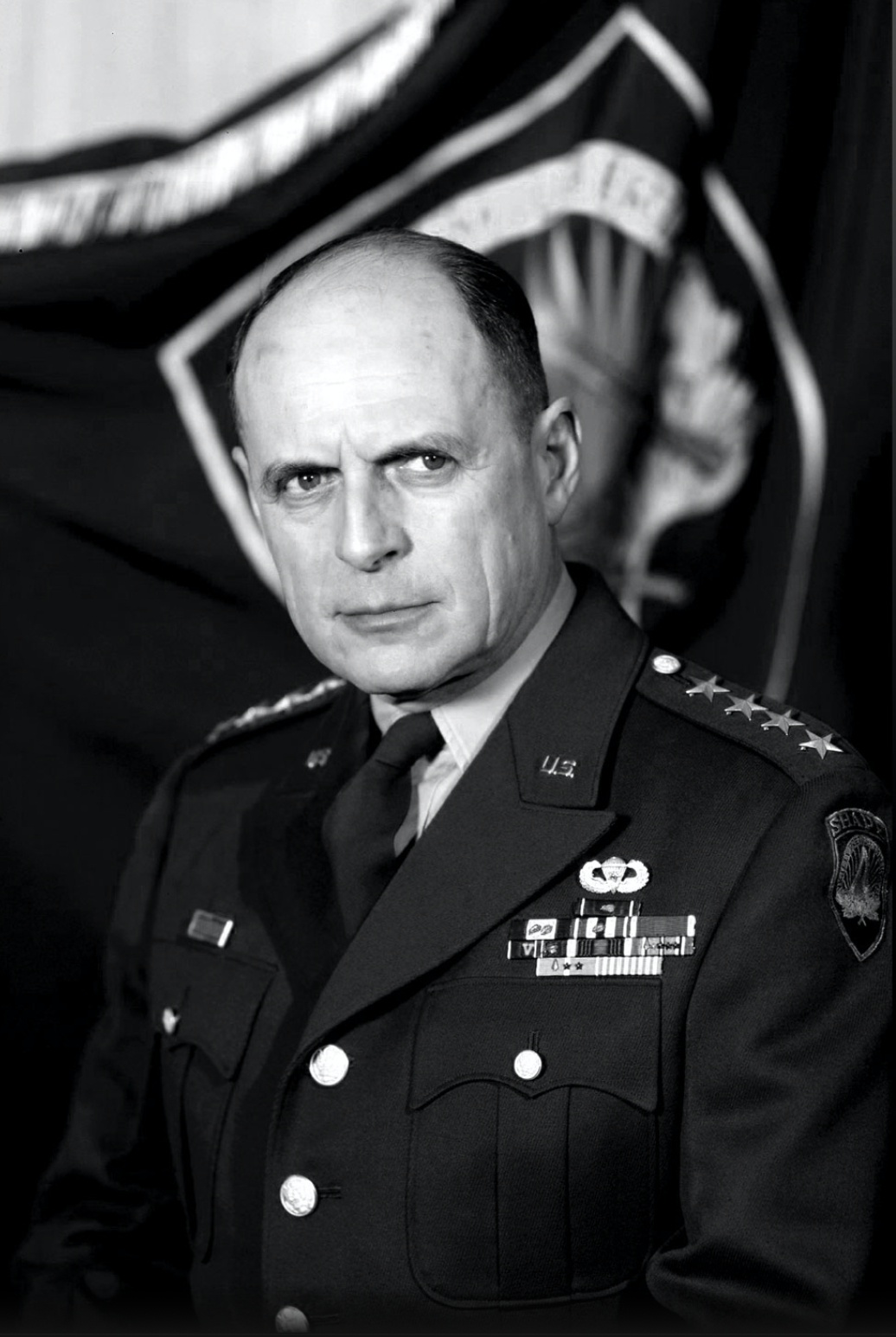

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway (March 3, 1895 - July 26, 1993) was a distinguished United States Army officer renowned for his pivotal leadership during World War II and the Korean War. He served as the first Commanding General of the 82nd Airborne Division, leading its forces in major campaigns across Sicily, Italy, and Normandy. Following this, he commanded the XVIII Airborne Corps through critical engagements including the Battle of the Bulge, Operation Varsity, and the Western Allied invasion of Germany until the end of World War II.

After the war, Ridgway held several significant commands, but he is most recognized for his crucial role in revitalizing the United Nations (UN) war effort during the Korean War, where he assumed command of the Eighth United States Army and later became the Supreme Commander of United Nations Forces. Historians widely credit Ridgway with turning the tide of the war in favor of the UN. As Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) in Japan, he oversaw the restoration of Japan's sovereignty. Furthermore, Ridgway played a critical part in dissuading President Dwight D. Eisenhower from direct military intervention in the First Indochina War, a decision that significantly delayed deeper United States involvement in what would become the Vietnam War. For his extensive and distinguished military career, Ridgway was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan on May 12, 1986. He died in 1993 at the age of 98.

2. Early Life and Education

Matthew Bunker Ridgway was born on March 3, 1895, in Fort Monroe, Virginia. His father was Colonel Thomas Ridgway, an artillery officer, and his mother was Ruth Starbuck (Bunker) Ridgway. Ridgway spent his childhood immersed in military life, living on various military bases due to his father's assignments. He later reflected on these formative years, stating that his "earliest memories are of guns and marching men, of rising to the sound of the reveille gun and lying down to sleep at night while the sweet, sad notes of 'Taps' brought the day officially to an end."

In 1912, Ridgway graduated from The English High School in Boston. Influenced by his father, a West Point alumnus, Ridgway applied to the academy, believing it would please his father. His first attempt to pass the entrance examination was unsuccessful due to his inexperience with mathematics. However, after dedicated self-study, he successfully passed the exam on his second attempt and was admitted. During his time at West Point, he served as the manager of the football team. He graduated on April 20, 1917, just two weeks after the American entry into World War I, receiving his commission as a second lieutenant in the Infantry Branch of the United States Army. His graduating class included many future generals, such as J. Lawton Collins, Mark W. Clark, Ernest N. Harmon, Norman Cota, and Maxwell D. Taylor.

3. Early Military Career (Pre-World War II)

Ridgway began his military career during World War I, though he was disappointed not to see combat duty. He was initially assigned to border duties with Mexico as a member of the 3rd Infantry Regiment. Subsequently, he served on the West Point faculty as an instructor in Spanish. He expressed a deep regret about not participating in the war, feeling that "the soldier who had had no share in this last great victory of good over evil would be ruined."

From 1924 to 1925, Ridgway attended the company officers' course at the United States Army Infantry School in Fort Benning, Georgia. Following this, he took command of a company within the 15th Infantry Regiment stationed in Tianjin, China. His service then led him to Nicaragua, where he contributed to supervising free elections in 1927.

In 1930, Ridgway was appointed as an advisor to the Governor-General of the Philippines. He furthered his education by graduating from the United States Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1935, and from the United States Army War College at Washington Barracks, District of Columbia, in 1937. Throughout the 1930s, he held various staff positions, including Assistant Chief of Staff of VI Corps, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Second Army, and Assistant Chief of Staff of the Fourth Army. His notable performance led General George C. Marshall, then Chief of Staff of the United States Army, to assign Ridgway to the War Plans Division shortly after the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939.

4. World War II

Ridgway's involvement in World War II saw his rapid rise through the ranks. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on July 1, 1940, and served in the War Plans Division until January 1942. After a temporary promotion to colonel on December 11, he was promoted to the one-star general officer rank of brigadier general in January 1942. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Ridgway was swiftly promoted from lieutenant colonel to major general within a mere four months.

In February 1942, he was assigned as Assistant Division Commander of the 82nd Infantry Division, which was then forming under the command of Major General Omar Bradley. Ridgway held deep respect for Bradley, and together they trained thousands of new recruits. In August, after Bradley's reassignment, Ridgway was promoted to major general and given command of the 82nd Division. The 82nd, already distinguished from its World War I service, was selected to become one of the U.S. Army's pioneering airborne divisions. This conversion was unprecedented, requiring extensive training, testing, and experimentation. Consequently, on August 15, 1942, the division was redesignated as the 82nd Airborne Division.

Initially, the division was to comprise the 325th, 326th, and 327th Infantry Regiments, all intended for conversion to glider infantry. However, the 327th was soon transferred to help form the 101st Airborne Division. Unlike his troops, Ridgway did not attend airborne jump school prior to joining the division, but he earned his paratrooper wings during his command. He successfully transformed the 82nd into a combat-ready airborne unit. The 327th was replaced by the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, initially commanded by Colonel Theodore Dunn and later by Lieutenant Colonel Reuben Tucker. In February 1943, the 326th was also transferred and replaced by the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, under Colonel James M. Gavin. By April, the 82nd, despite receiving only one-third of the training time typically given to divisions, was deployed to North Africa in preparation for the invasion of Sicily.

4.1. Italian Campaign

Ridgway played a key role in planning the airborne component of the Allied invasion of Sicily, codenamed Operation Husky, which commenced in July 1943. The invasion was spearheaded by Colonel Gavin's 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, reinforced into the 505th Parachute Regimental Combat Team. Despite some successes, the operation proved devastating for the airborne division. Due to unforeseen circumstances, including significant friendly fire, the 82nd suffered heavy casualties in Sicily, including the division's Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Charles L. Keerans. Following the widely scattered drop of the 504th on the morning of July 9, Ridgway had to report to Lieutenant General George S. Patton, commander of the Seventh United States Army, that out of more than 5,300 paratroopers who had jumped, he had fewer than 400 under his control.

During the planning for the invasion of the Italian mainland, the 82nd was initially tasked with capturing Rome by coup de main in Operation Giant II. Ridgway vehemently opposed this unrealistic plan, which proposed dropping the 82nd on the outskirts of the Italian capital amidst two strong German divisions. His strong objections led to the cancellation of the operation just hours before its scheduled launch. However, the 82nd played a crucial role in the Allied invasion of Italy at Salerno in September. A timely drop by Ridgway's two parachute regiments was instrumental in preventing the Allies from being pushed back into the sea. The 82nd Airborne Division then saw brief service in the early stages of the Italian Campaign, assisting the Allies in breaching the Volturno Line in October. The division subsequently moved to occupation duties in the recently liberated city of Naples before departing for Northern Ireland in November. Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, commander of the Fifth United States Army and a fellow West Point graduate, lauded Ridgway as an "outstanding battle soldier, brilliant, fearless and loyal," who had "trained and produced one of the finest Fifth Army outfits." As a compromise, Colonel Tucker's 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, along with supporting units, was retained in Italy, with the understanding that they would rejoin the rest of the 82nd Airborne Division as soon as feasible.

4.2. Western Front and German Invasion

In late 1943 and early 1944, after the 82nd Airborne Division's deployment to Northern Ireland, Ridgway was instrumental in planning the airborne operations for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy. He successfully argued for an increase in the strength of the two American airborne divisions participating in the invasion (the 82nd and the inexperienced 101st Airborne Division), from two parachute regiments and a single glider regiment to three parachute regiments, and for the glider regiment to have three battalions.

During the Battle of Normandy, Ridgway famously jumped with his troops, fighting for 33 days to advance to Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte near Cherbourg, which was liberated on June 14, 1944. Relieved from front-line duty in early July, the 82nd Airborne Division had sustained 46 percent casualties during the severe fighting in the Normandy bocage.

In August 1944, Ridgway was given command of XVIII Airborne Corps, with command of the 82nd Airborne Division passing to Brigadier General James M. Gavin, his former Assistant Division Commander. Ridgway's corps saw action in Operation Market Garden, with the 101st Airborne Division dropping near Eindhoven to secure bridges. Ridgway personally dropped with his troops and was at the forefront of the fighting. The XVIII Airborne Corps played a critical role in stopping and pushing back German forces during the Battle of the Bulge in December. In March 1945, with the British 6th Airborne Division and United States 17th Airborne Division under his command, he led the corps into Germany during Operation Varsity, the airborne component of Operation Plunder. He was wounded in the shoulder by German grenade fragments on March 24, 1945. He continued to lead the corps through the Western Allied invasion of Germany. On June 4, 1945, he was promoted to the temporary rank of lieutenant general.

At the war's conclusion, Ridgway was en route to a new assignment in the Pacific theater of war under General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, with whom he had served as a captain at West Point. Ridgway held high regard for British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, describing his time serving under Montgomery as "most satisfying." He noted that Montgomery "gave me the general outline of what he wanted and let me completely free," and referred to him as "a first-class professional officer of great ability ... and Monty could produce ... I don't know anybody who could give me more complete support than Monty did when I was under British command twice ... I had no trouble with Monty at all."

5. Post-War Military Career

After the dissolution of the XVIII Airborne Corps in October 1945, Ridgway commanded U.S. forces in Luzon. He was subsequently appointed Deputy Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean, leading United States forces in the Mediterranean Theater. From 1946 to 1948, he served as the United States Army representative on the military staff committee of the United Nations.

In 1948, Ridgway was placed in charge of the Caribbean Command, overseeing United States forces in the Caribbean Sea. The following year, 1949, he was assigned as Deputy Chief of Staff for Administration under then Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General J. Lawton Collins.

6. Korean War

Ridgway's most significant command assignment came during the Korean War, where he played a pivotal role in changing the course of the conflict.

6.1. Command of Eighth Army

On December 23, 1950, Ridgway was assigned as the replacement for Lieutenant General Walton Walker in command of the Eighth United States Army in South Korea. At this time, the Eighth Army was in a tactical retreat following an unexpected and overwhelming Communist Chinese advance during the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River.

Upon assuming command of the battered Eighth Army, one of Ridgway's immediate priorities was to restore the morale and confidence of his soldiers. He initiated a significant reorganization of the command structure. During an early briefing in Korea at I Corps, Ridgway listened to an extensive discussion of defensive plans before asking about attack plans. When the corps G-3 (operations officer) admitted to having none, Ridgway promptly replaced him. He also removed officers who failed to conduct patrols to ascertain enemy locations and insisted on the removal of "enemy positions" from planning maps if local units had not recently verified their presence. Ridgway implemented a plan to rotate out division commanders who had been in action for six months, replacing them with fresh leaders. He issued clear guidance to commanders at all levels, urging them to spend more time on the front lines and less in their rear command posts. These decisive actions had an immediate positive effect on morale.

With China's entry into the war, the nature of the Korean War changed significantly. Political leaders, aiming to prevent the expansion of the conflict, prohibited UN forces from bombing supply bases in China or bridges across the Yalu River on the China-North Korea border. The American army shifted from an aggressive stance to fighting protective, delaying actions. Ridgway's second major tactical change was to make extensive use of artillery. Chinese casualties began to mount significantly as they launched waves of attacks into the coordinated artillery fire. Under Ridgway's leadership, the Chinese offensive was slowed and ultimately halted at the battles of Chipyong-ni and Wonju. He then led his troops in Operation Thunderbolt, a successful counter-offensive in early 1951. He earned the nickname "Tin Tits" for his habit of wearing hand grenades attached to his load-bearing equipment at chest level, though photographs reveal he typically carried only one grenade on one side, with an emergency first aid packet on the other.

6.2. Supreme UN Commander and SCAP

When General Douglas MacArthur was relieved of command by President Harry S. Truman in April 1951, Ridgway was promoted to full general and assumed command of all United Nations forces in Korea. As commanding general in Korea, he oversaw the desegregation and integration of United States Army units in the Far East Command, a policy that profoundly influenced the wider army's subsequent desegregation. Ridgway also continued the bombing of North Korea, which led to the widespread destruction of much of the country's infrastructure and resulted in significant civilian casualties. The number of Korean casualties by war's end, dead, injured, or missing, approached three million, representing ten percent of the overall population, with the majority of fatalities occurring in the North.

In 1951, Ridgway was elected an honorary member of the Virginia Society of the Cincinnati.

Concurrently with his role as UN Commander, Ridgway assumed MacArthur's duties as the military governor of Japan, serving as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). During his tenure as SCAP, Ridgway collaborated closely with Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida to facilitate Japan's return to independence. He notably oversaw the restoration of Japan's independence and sovereignty on April 28, 1952, with the coming into force of the Treaty of San Francisco. He reportedly expressed frustration with the South Korean Army's tendency to abandon advanced equipment, noting that despite being supplied with modern weaponry, Korean soldiers would often discard expensive gear during retreats, which concerned him. He concluded that it was necessary to withdraw all South Korean divisions from the front lines for a period of intensive training.

7. Cold War Era Commands and Policies

Following his service in the Korean War, Ridgway held key leadership roles during the height of the Cold War, influencing American military strategy and policy.

7.1. Supreme Allied Commander, Europe (SACEUR)

In May 1952, Ridgway succeeded General Dwight D. Eisenhower as the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) for the nascent North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). During his time in this position, Ridgway made substantial progress in developing a coordinated NATO command structure, overseeing an expansion of forces and facilities, and improving training and standardization across the alliance. However, he faced some friction with other European military leaders due to his tendency to surround himself with American staff. His direct and truthful communication style was not always politically expedient. In a 1952 review, General Omar Bradley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, reported to President Harry S. Truman that "Ridgway had brought NATO to 'its realistic phase' and a 'generally encouraging picture of how the heterogeneous defense force is being gradually shaped.'"

Ridgway also controversially urged the Anglo-French-American high commissioners for Germany to pardon all German officers convicted of war crimes on the Eastern Front of World War II. He asserted that his "honor as a soldier" compelled him to insist on the release of these officers before he could "issue a single command to a German soldier of the European army," noting that he himself had recently given orders in Korea "of the kind for which the German generals are sitting in prison."

7.2. Chief of Staff of the United States Army

On August 17, 1953, Ridgway succeeded General J. Lawton Collins as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army. After Eisenhower's election as president, he sought Ridgway's assessment regarding potential United States military involvement in Vietnam alongside French forces. Ridgway prepared a comprehensive and detailed outline of the massive commitment that would be necessary for success in such an intervention, a report that significantly dissuaded the President from intervening directly.

A consistent source of tension during his tenure was Ridgway's belief that air power and nuclear weapons did not diminish the fundamental need for powerful, mobile ground forces to seize land and control populations. He was deeply concerned that Eisenhower's proposals to significantly reduce the size of the army would leave it vulnerable and unable to effectively counter the growing Soviet military threat, a concern underscored by events like the 1954 Alfhem affair in Guatemala. These disagreements over military expenditures and strategic priorities led to recurring friction throughout his term as Chief of Staff. Ridgway was a prominent leader of the "Never Again Club" within the U.S. Army, a group that viewed the Korean War's inconclusive outcome as a significant setback and strongly opposed engaging in another large-scale land war in Asia, especially against China.

In the spring of 1954, Ridgway was vehemently opposed to Operation Vulture, a proposed American intervention in Vietnam using tactical nuclear weapons to prevent the French defeat at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Arthur W. Radford, supported Operation Vulture and recommended it to Eisenhower, arguing that the United States could not permit a Communist victory. While the chief of the French general staff, General Paul Ély, visited Washington on March 20, 1954, Radford showed him the plans for Vulture, giving the impression that the United States was committed. In a strong dissenting opinion, Ridgway argued that airpower alone, even with tactical nuclear weapons, would not be enough to save the French. He contended that only the commitment of at least seven American infantry divisions, and possibly up to ten or even twelve divisions, could save the French at Dien Bien Phu, and he accurately predicted that if the United States intervened, China would too. Ridgway emphasized that the United States becoming bogged down in another land war in Asia, fighting the Chinese again so soon after the Korean War, would be a costly distraction from Europe, a theater he considered far more strategically vital than Vietnam. In his dissenting report to Eisenhower, Ridgway stated that "Indochina is devoid of decisive military objectives" and that fighting a war there "would be a serious diversion of limited U.S. capabilities." He believed that Radford, as an admiral, underestimated Chinese military power and the dangers of another protracted conflict against them.

Ridgway's objections to Operation Vulture gave Eisenhower pause. Despite strong lobbying from Vice President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in favor of Vulture, and Radford's insistent belief that three tactical atomic bombs could save the French, Eisenhower remained indecisive. Eisenhower himself harbored guilt over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, once reportedly telling Radford and Air Force General Nathan F. Twining, "You boys must be crazy. We can't use those awful things against Asians for a second time in less than ten years. My God!" Eisenhower ultimately agreed to carry out Vulture only if Congress approved it first and if Great Britain agreed to join. Congress gave an equivocal answer, rejecting the idea of Vulture as a purely American operation but willing to support it as an Anglo-American endeavor. However, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ultimately rejected British intervention in Vietnam, which effectively killed Operation Vulture. On May 7, 1954, the remaining French forces at Dien Bien Phu surrendered, leading to the collapse of the French government and the formation of a new government under Pierre Mendès France, whose sole mandate was to withdraw all French forces from Indochina.

President Eisenhower approved a waiver to the military's mandatory retirement policy at age 60, allowing Ridgway to complete his two-year term as Chief of Staff. However, persistent disagreements with the administration over its policy of downgrading the army in favor of the United States Navy and the United States Air Force prevented Ridgway from being appointed to a second term. Ridgway retired from the army on June 30, 1955, and was succeeded by General Maxwell D. Taylor, his former chief of staff from the 82nd Airborne Division. Even after retirement, Ridgway remained a consistent critic of President Eisenhower. During the second 1960 presidential debate on October 7, John F. Kennedy cited General Ridgway as a supporter of the position that the United States should not attempt to defend Quemoy and Matsu from attack by the People's Republic of China.

7.3. Stance on Vietnam War and "Wise Men"

In November 1967, Ridgway was invited to join the "Wise Men," an influential group of retired diplomats, politicians, and generals who periodically convened to offer advice on the Vietnam War to President Lyndon B. Johnson. While the group, informally led by former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, was sometimes dismissed as a public relations maneuver, President Johnson held them in high regard and took their counsel seriously.

In early 1968, Ridgway, alongside General James M. Gavin and General David M. Shoup, publicly expressed their opposition to the strategic bombing offensive against North Vietnam. They declared that South Vietnam was not worth the extensive effort required to defend it. This criticism reportedly unsettled Johnson's powerful National Security Adviser, W.W. Rostow, who authored a five-page memorandum to the President arguing that Ridgway, Gavin, and Shoup were misinformed and expressed supreme confidence that the bombing campaign would soon force North Vietnam to surrender.

In the aftermath of the Tet Offensive and Johnson's narrow victory over anti-war Senator Eugene McCarthy in the New Hampshire Democratic primary, the White House was gripped by crisis. Johnson was torn between pursuing a military solution or a diplomatic one. Adding to the tension was a maneuver by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Earle Wheeler, to compel Johnson to abandon the diplomatic option and continue the military approach. On February 23, 1968, Wheeler instructed General William Westmoreland to advise Johnson to send an additional 206,000 troops to Vietnam, even though Westmoreland had not requested them. Under Wheeler's persistent prompting, Westmoreland submitted the request, insisting in his report that he could not win the war without these reinforcements. Wheeler's true intention was to force Johnson to call out the reserves and the state National Guard. By 1968, sending an additional 206,000 troops to join the half-million U.S. soldiers already in Vietnam would necessitate mobilizing the reserves and National Guard, as other American commitments in Europe and South Korea could not be abandoned. Such a mobilization would disrupt the economy, forcing Johnson to end the peacetime economy, a step that would make a diplomatic solution politically untenable. The economic sacrifices required by a wartime economy could only be justified to the American public by asserting a commitment to fight until victory.

As the debate over Westmoreland's troop request intensified, Clark Clifford, a long-time friend of Johnson's and a known hawk, arrived at the Pentagon on March 1, 1968, as the newly appointed Defense Secretary. Clifford's friend, Senator J. William Fulbright, arranged for him to meet privately with Ridgway and General Gavin. Both Ridgway and Gavin advised Clifford that victory in Vietnam was unattainable and that he should use his influence with Johnson to persuade him to seek a diplomatic solution. This advice from Ridgway and Gavin proved instrumental in converting Clifford from a hawk to a dove.

Defense Secretary Clifford, recognizing the profound political implications of the request for 206,000 more troops, vigorously lobbied Johnson to reject it, urging him to pursue a diplomatic solution, while Rostow continued to advise acceptance. Since Westmoreland's report stated that victory was impossible without the additional troops, rejecting the request would inherently mean abandoning the military solution. To resolve this critical debate, Johnson convened a meeting of the "Wise Men" on March 25, 1968. The following day, the majority of the "Wise Men" advised Johnson that victory in Vietnam was indeed impossible and that he should seek a diplomatic resolution. This counsel was decisive in persuading Johnson to initiate peace talks. Of the fourteen "Wise Men," only General Maxwell Taylor, Robert Murphy, Abe Fortas, and General Omar Bradley advocated for continuing a military solution; all others spoke for a diplomatic approach. Ridgway's status as a respected war hero, whom no one could accuse of being "soft on Communism," further enhanced the prestige of the "Wise Men" and made Johnson more inclined to accept their advice. On March 31, 1968, Johnson addressed the nation on television, announcing his willingness to open peace talks with North Vietnam, an unconditional halt to bombing most of North Vietnam, and his decision to withdraw from the 1968 presidential election.

8. Personal Life

Matthew Ridgway's personal life involved three marriages. In 1917, he married Julia Caroline Blount (1895-1986), with whom he had two daughters, Constance and Shirley, before they divorced in 1930.

Shortly after his first divorce, Ridgway married Margaret ("Peggy") Wilson Dabney (1891-1968), the widow of a West Point graduate. In 1936, he adopted Peggy's daughter, Virginia Ann Dabney (1919-2004). This marriage ended in divorce in June 1947. Later that same year, he married Mary Princess Anthony Long (1918-1997), affectionately known as "Penny." They remained married for 46 years until his death. Together, they had one son, Matthew Bunker Ridgway, Jr., who tragically died in an accident in 1971 shortly after graduating from Bucknell University and receiving his commission as a second lieutenant through the Reserve Officers' Training Corps. Penny Ridgway died in 1997.

In retirement, Ridgway relocated to the Pittsburgh suburb of Fox Chapel, Pennsylvania, in 1955. He remained active, accepting the chairmanship of the board of trustees of the Mellon Institute and a position on the board of directors of Gulf Oil Corporation, among other roles. In 1960, he retired from the Mellon Institute but continued to serve on numerous corporate boards, Pittsburgh civic groups, and Pentagon strategic study committees.

He consistently advocated for a strong military, to be used judiciously. Ridgway delivered many speeches, wrote articles, and participated in various panels and discussions. In early 1968, he met privately with President Johnson and Vice President Hubert Humphrey after a White House luncheon to discuss Indochina. When asked for his opinion, Ridgway advised against deeper involvement in Vietnam and against using force to resolve the Pueblo Incident. In an article for Foreign Affairs, Ridgway argued that political goals should align with vital national interests and that military goals should consistently support political objectives, noting that neither condition was met in the Vietnam War. He also advocated for maintaining a chemical, biological, and radiological weapons capability, believing they could achieve national goals more effectively than existing armaments. In 1976, Ridgway was a founding board member of the Committee on the Present Danger, which pressed for increased military preparedness in response to a perceived escalating Soviet threat.

On May 5, 1985, Ridgway participated in U.S. President Ronald Reagan's controversial visit to Kolmeshöhe Cemetery near Bitburg. In an unscheduled moment, former Luftwaffe ace fighter pilot Johannes Steinhoff firmly shook Ridgway's hand in a powerful gesture of reconciliation between the former adversaries.

9. Writings and Publications

Matthew B. Ridgway authored two significant autobiographical works that provided insights into his military career and strategic thinking. In 1956, the year after his retirement, he published his autobiography, Soldier: The Memoirs of Matthew B. Ridgway, which recounted his life and experiences. In 1967, he released The Korean War, offering his perspective and analysis of the conflict in which he played a central role.

10. Death and Burial

Matthew Bunker Ridgway died at his home in Fox Chapel, a suburb of Pittsburgh, on July 26, 1993, at the age of 98. The cause of death was cardiac arrest. He was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery, located in Arlington, Virginia.

At his graveside eulogy, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, honored Ridgway, stating: "No soldier ever performed his duty better than this man. No soldier ever upheld his honor better than this man. No soldier ever loved his country more than this man did. Every American soldier owes a debt to this great man."

11. Legacy and Reception

Matthew Ridgway is widely remembered as an influential military leader whose strategic insights and leadership deeply impacted key moments in 20th-century history.

11.1. Positive Reception and Contributions

Throughout his distinguished career, Ridgway was consistently recognized as an outstanding leader, earning the profound respect of his subordinates, peers, and superiors. General Omar Bradley notably described Ridgway's accomplishments in turning the tide of the Korean War as "the greatest feat of personal leadership in the history of the Army." His leadership in combat was particularly inspiring; a soldier in Normandy vividly recalled an intense battle while attempting to cross a crucial bridge, stating: "The most memorable sight that day was Ridgway, Gavin, and Maloney standing right there where it was the hottest [heaviest incoming fire]. The point is that every soldier who hit that causeway saw every general officer and the regimental and battalion commanders right there. It was a truly inspirational effort."

During the critical Battle of the Bulge, on the day of the Germans' furthest advance, Ridgway famously addressed his subordinate officers in the XVIII Airborne Corps with unwavering confidence: "The situation is normal and completely satisfactory. The enemy has thrown in all his mobile reserves, and this is his last major offensive effort in this war. This Corps will halt that effort; then attack and smash him."

Ridgway articulated his philosophy of leadership as resting upon three primary ingredients: character, courage, and competence. He considered character-encompassing self-discipline, loyalty, selflessness, modesty, and the willingness to accept responsibility and admit mistakes-as the "bedrock on which the whole edifice of leadership rests." His concept of courage embraced both physical bravery and moral fortitude. Competence, for Ridgway, included physical fitness, the ability to anticipate and be present to resolve crises, and a close relationship with subordinates, characterized by clear communication and ensuring their fair treatment and effective leadership. In 2011, the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College published a monograph on Ridgway, highlighting how he overcame his own shortcomings through the painful experiences of three intense battles (Husky, Neptune, and Market) to master operational art. He learned from these initial failures, progressively applying operational skills in the Bulge and Varsity battles, ultimately achieving mastery in the fifth combat experience.

11.2. Criticism and Controversies

Despite his widespread acclaim, certain aspects of Ridgway's career drew criticism or generated controversy. His decision to continue the extensive bombing of North Korea during his tenure as UN Commander led to the destruction of significant infrastructure and caused numerous civilian casualties, impacting a large portion of the population.

His controversial stance as Supreme Allied Commander, Europe (SACEUR), urging the pardon of German officers convicted of war crimes on the Eastern Front, was met with resistance from some European leaders. Ridgway argued that his "honor as a soldier" necessitated their release before he could effectively command German soldiers in a European army, equating their actions to orders he had given in Korea.

Furthermore, Ridgway's tenure as Chief of Staff of the United States Army was marked by recurring disagreements with President Dwight D. Eisenhower concerning military expenditures. Ridgway consistently argued for the necessity of strong, mobile ground forces, contending that air power and nuclear weapons alone were insufficient for achieving decisive military objectives, particularly in countering the growing Soviet threat. These fundamental disagreements ultimately contributed to his not being appointed for a second term as Chief of Staff. Additionally, during the Korean War, Ridgway expressed considerable frustration with the South Korean Army for their tendency to abandon modern and expensive equipment, a challenge he sought to address through intensive training programs.

12. Major Assignments

- Staff Officer, War Plans Division - December 24, 1941 to February 19, 1942

- Assistant Division Commander, 82nd Infantry Division - February 19, 1942 to June 26, 1942

- Commander, 82nd Airborne Division - June 26, 1942 to August 27, 1944

- Commander, XVIII Airborne Corps - August 27, 1944 to October 1945

- Deputy Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean - October 1945 to 1946

- U.S. Army Representative to the Military Staff Committee of the United Nations - 1946 to June 1948

- Commander, United States Caribbean Command - June 1948 to October 1949

- Deputy Chief of Staff for Administration - November 1949 to December 24, 1950

- Commander, Eighth United States Army - December 26, 1950 to April 11, 1951

- Commander, United Nations Command Korea - April 11, 1951 to May 12, 1952

- Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) - April 11, 1951 to April 28, 1952

- Commander in Chief, United States Far East Command - April 11, 1951 to May 12, 1952

- Supreme Allied Commander Europe for NATO - May 30, 1952 to July 11, 1953

- Commander, United States Army European Command (EUCOM) - May 30, 1952 to August 1, 1952

- Commander in Chief, United States European Command (USEUCOM) - August 1, 1952 to July 11, 1953

- Chief of Staff of the United States Army - August 17, 1953 to June 30, 1955

13. Promotions

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Cadet | United States Military Academy | June 14, 1913 |

| Second lieutenant | Regular Army | April 20, 1917 | |

| First lieutenant | Regular Army | May 15, 1917 | |

| Captain | National Army | August 5, 1917 | |

| Captain | Regular Army | July 18, 1919 | |

| Major | Regular Army | October 1, 1932 | |

| Lieutenant colonel | Regular Army | July 1, 1940 | |

| Colonel | Army of the United States | December 11, 1941 |

| Brigadier general | Army of the United States | January 15, 1942 | |

| Major general | Army of the United States | April 6, 1942 |

| Lieutenant general | Army of the United States | June 4, 1945 |

| Brigadier general | Regular Army | November 1, 1945 | |

| Major general | Regular Army | Retroactive to April 6, 1942 |

| General | Army of the United States | May 11, 1951 |

| General | Regular Army, Retired | June 30, 1955 |

14. Honors and Awards

Matthew B. Ridgway received numerous military decorations and awards from the United States and other nations, recognizing his distinguished service and leadership.

14.1. United States badges, decorations and medals

| Combat Infantryman Badge (Ridgway is one of five general officers who have been awarded the honorary CIB for service while a general officer, along with General Joseph Stilwell, Major General William F. Dean, General of the Army Omar Bradley, and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Generals are typically not allowed to be awarded the CIB, as it is generally reserved for colonels and below.) |

| Combat Parachutist Badge with one bronze jump star |

| Army Staff Identification Badge |

| French Fourragère in the colors of WWII |

| Six Overseas Service Bars |

| Army Distinguished Service Cross with oak leaf cluster |

| Army Distinguished Service Medal with four oak leaf clusters |

| Silver Star with two oak leaf clusters |

| Legion of Merit with oak leaf cluster |

| Bronze Star with "V" device and oak leaf cluster |

| Purple Heart |

| Army Presidential Unit Citation |

| Presidential Medal of Freedom |

| World War I Victory Medal |

| Second Nicaraguan Campaign Medal |

| American Defense Service Medal with one bronze service star |

| American Campaign Medal |

| European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with Arrowhead device and eight campaign stars |

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal |

| World War II Victory Medal |

| Army of Occupation Medal with "Germany" clasp |

| National Defense Service Medal |

| Korean Service Medal with seven campaign stars |

14.2. International and foreign orders, decorations and medals

| Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor of France (1953) |

| Order of the Crown (Belgium), Grand Cross |

| Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, Knight Grand Cross (Italy) |

| Order of George I, Grand Cross (Greece) |

| Order of the Oak Crown, Grand Cross (Luxembourg) |

| Order of the Aztec Eagle, Grand Cross (Mexico) |

| Order of Orange-Nassau, Knight Grand Cross (The Netherlands) |

| Military Order of Aviz, Grand Cross (Portugal) |

| Order of Saint-Charles, Grand Officer (Monaco) |

| Order of Merit of the Italian Republic, Knight Grand Cross |

| Order of the White Elephant, 1st Class (Thailand) |

| Order of the Bath, Knight Commander (Great Britain) |

| Order of the Red Banner (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) |

| Order of Boyacá, Grand Officer (Colombia) |

| Military Order of Savoy, Grand Officer (Italy) |

| Philippine Legion of Honor, Chief Commander |

| Order of Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Grand Officer (Panama) |

| Order of Leopold II, Commander with palm (Belgium) |

| Order of the Southern Cross, Officer (Brazil) |

| Croix de Guerre (France) with bronze palm | |

| Croix de guerre (Belgium), WWII with bronze palm |

| United Nations Korea Medal |

| Inter-American Defense Board Medal |

| Korean War Service Medal |

14.3. Other honors

- Congressional Gold Medal

- The National Infantry Association awarded him their annual Doughboy Award.

- Ridgway appeared on the April 30, 1951, and May 12, 1952, covers of Life magazine.

- Ridgway appeared on the March 5, 1951, and July 16, 1951, covers of Time magazine.

15. Namesakes and Memorials

Several places, institutions, and entities have been named in honor of Matthew B. Ridgway, commemorating his legacy.

- Ridgway was honored by his adopted hometown of Pittsburgh with the renaming of the entrance to the Soldiers and Sailors National Military Museum and Memorial, located in the city's education and cultural district, to "Ridgway Court."

- The Matthew B. Ridgway Center for International Security Studies at the University of Pittsburgh bears his name.

- Ridgway is the namesake of the mascot for the Houston Astros' Single-A baseball team, the Fayetteville Woodpeckers.

- The reading room for special collections at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center is named Ridgway Hall.