1. Early Life and Background

Henri Mouhot was born on May 15, 1826, in Montbéliard, Doubs, France, a town situated near the Swiss border. During his early life, he spent a decade in Russia, where he pursued linguistic studies as a young professor. This period of his childhood and early adulthood in Russia, potentially in its Asian regions, broadened his perspective before he began his scientific endeavors.

1.1. Education and Early Career

Mouhot traveled extensively throughout Europe with his brother, Charles, where they studied photographic techniques, including those developed by Louis Daguerre. In 1856, he shifted his focus to the study of natural science, a field he would dedicate himself to for the remainder of his life. In the same year, he married the daughter of the Scottish explorer Mungo Park.

1.2. Decision to Explore

Mouhot's decision to embark on expeditions to Southeast Asia was significantly influenced by his reading of The Kingdom and People of Siam by Sir John Bowring in 1857. Inspired by this work, he resolved to travel to Indochina to conduct a series of botanical expeditions with the goal of collecting new zoological specimens. His initial attempts to secure funding and passage were met with rejection from French companies and the government of Napoleon III. However, his persistence paid off when the Royal Geographical Society and the Zoological Society of London lent him their support. With this backing, he set sail for Bangkok, via Singapore, in 1858.

2. Expeditions in Southeast Asia

From his base in Bangkok, established in 1858, Henri Mouhot undertook four major journeys into the interior regions of Siam (modern-day Thailand), Cambodia, and Laos. Over a period of three years before his death, he faced immense challenges, enduring extreme hardships and fending off wild animals as he explored vast, previously uncharted jungle territories. His explorations covered a total distance of 3.1 K mile (4.96 K km) over three years, six months, and thirteen days.

2.1. Overview of Expeditions

Mouhot's expeditions were characterized by their extensive scope and the significant challenges he encountered. He meticulously documented his travels, which involved navigating dense jungles, facing the dangers of local wildlife, and enduring the physical toll of long journeys in a demanding climate. Despite these difficulties, he successfully collected a wide array of natural specimens and made detailed observations of the regions he traversed.

2.2. Major Routes and Itinerary

Mouhot's four expeditions followed specific routes, each contributing to his comprehensive documentation of the region.

- First Expedition (159 mile (256 km)): Beginning from Bangkok, Mouhot traveled to Ayutthaya, the former capital of Siam. Although this area had already been charted, he used the opportunity to gather an extensive collection of insects, as well as terrestrial and river shells, which he subsequently sent to England.

- Second Expedition (1.5 K mile (2.40 K km)): This was Mouhot's longest journey. It commenced from Bangkok, leading him along the coast to Chanthaburi, and then to islands such as Ko Chang and Ko Kood. He proceeded to Oudongk and Phnom Penh in Cambodia, staying with the Stieng tribe in Bro Lam Peh. His return route took him via Tonlé Sap Lake, the Angkor ruins, Battambang, and Kabinburi before returning to Bangkok. It was during this expedition, in January 1860, that he reached Angkor.

- Third Expedition (0.8 K mile (1.25 K km)): This journey saw Mouhot travel from Bangkok to Phetchaburi, then back to Bangkok, before heading north to Lopburi, Ayutthaya, Tha Ruea, Sao Hai, Wat Tha Khlo Tai, Chaiyaphum, and Saraburi, eventually returning to Bangkok.

- Fourth Expedition (0.7 K mile (1.05 K km)): His final expedition began from Bangkok, taking him to Si Khiu, Nakhon Ratchasima, Prasat Phanom Wan, Chaiyaphum, Non Kok, Phu Khiao, Loei, Pak Lay, Tha Deua, and finally to Luang Prabang and Na Le in Laos, where he eventually succumbed to illness.

The detailed itinerary of his journeys, as recorded in Le Tour du Monde (the "Around the World" journal), is as follows:

| Stage | Locality (period name) | Locality (current name) | Chapter from Le Tour du Monde | Arrival | Departure |

| Preparation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | London | London | I | 27 April 1858 | |

| 2 | Singapore | Singapore | I | 3 September 1858 | |

| 3 | Paknam | Pak Nam | I | 12 September 1858 | |

| 4 | Bangkok | Bangkok | II - V | 19 October 1858 | |

| First expedition (159 mile (256 km)) | |||||

| 5 | Ajuthia | Ayutthaya | VI | 23 October 1858 | |

| 6 | Arajiek, Phrabat | Phra Phuttabat | VII | 13 November 1858 | 14 November 1858 |

| 7 | Patawi | Phra Phutthachai | VIII | 28 November 1858 | |

| 8 | Bangkok | Bangkok | VIII | 5 December 1858 | 23 December 1858 |

| Second expedition (1.5 K mile (2.40 K km)) | |||||

| 9 | Chantaboun Gulf, Lion's Rock | Laem Sing | IX | 3 January 1859 | |

| 10 | Chantaboun | Chanthaburi | IX | 4 January 1859 | |

| 11 | Ile de Ko-Man | Ko Man Nork | IX | 26 January 1859 | |

| 12 | Ile des Patates et ile de Ko-Kram | Ko Khram | IX | 28 January 1859 | |

| 13 | Ile de l'Arec | Chanthaburi | X | 29 January 1859 | |

| 14 | Ven-Ven | Pak Nam Welu | X | 1 March 1859 | |

| 15 | Chute de Kombau, grotte du Mont Sabab | Namtok Phlio National Park | X | ||

| 16 | Chantaboun | Chanthaburi | XI | ||

| 17 | Ko-Khut | Ko Kood | XI | ||

| 18 | Koh-Khong | Koh Kong | XI | ||

| 19 | Kampot | Kampot | XI | ||

| 20 | Kompong-Baïe | Kompong Bay | XI | ||

| 21 | Udong | Oudongk | XII | ||

| 22 | Pinhalu | Ponhea Leu | XIII | 2 July 1859 | |

| 23 | Penom Penh | Phnom Penh | XIV | ||

| 24 | Ile de Ko Sutin | Kaoh Soutin | XV | ||

| 25 | Pemptiélan | Peam Chilӗang | XV | ||

| 26 | Brelum | Bro Lam Peh | XV | 16 August 1859 | 29 November 1859 |

| 27 | Pemptiélan | Peam Chilӗang | XVI | ||

| 28 | Pinhalu | Ponhea Leu | XVI | 21 December 1859 | |

| 29 | Penom Penh | Phnom Penh | XVI | ||

| 30 | Lac du Touli-Sap | Tonlé Sap | XVI | ||

| 31 | Battambang | Battambang | XVII | 20 January 1860 | |

| 32 | Ongkor | Angkor | XVIII | 22 January 1860 | 12 February 1860 |

| 33 | Mont Ba-Khêng | Phnom Bakheng | XIX | ||

| 34 | Battambang | Battambang | XXI | 5 March 1860 | |

| 35 | Ongkor-Borège | Mongkol Borey | XXI | 8 March 1860 | 9 March 1860 |

| 36 | Muang Kabine | Kabinburi | XXI | 28 March 1860 | |

| 37 | Bangkok | Bangkok | XXI | 4 April 1860 | 8 May 1860 |

| Third expedition (0.8 K mile (1.25 K km)) | |||||

| 38 | Petchabury | Phetchaburi | XXII | 11 May 1860 | |

| 39 | Bangkok | Bangkok | XXIII | 1 September 1860 | |

| 40 | Nophabury | Lopburi | XXIV | ||

| 41 | Ajuthia | Ayutthaya | XXIV | 19 October 1860 | |

| 42 | Tharua-Tristard | Tha Ruea | XXIV | 20 October 1860 | |

| 43 | Saohaïe | Sao Hai | XXIV | 22 October 1860 | |

| 44 | Khao Koc | Wat Tha Khlo Tai | XXV | ||

| 45 | Tchaïapoune | Chaiyaphum | XXVI | 28 February 1861 | |

| 46 | Saraburi | Saraburi | XXVI | ||

| 47 | Bangkok | Bangkok | XXVI | 12 April 1861 | |

| Fourth expédition (0.7 K mile (1.05 K km)) | |||||

| 48 | Sikiéou | Si Khiu | XXVI | ||

| 49 | Korat | Nakhon Ratchasima | XXVI | ||

| 50 | Penom-Wat | Prasat Phanom Wan | XXVI | ||

| 51 | Tchaïapoune | Chaiyaphum | XXVII | ||

| 52 | Nam-Jasiea | Non Kok | XXVII | ||

| 53 | Poukiéau | Phu Khiao | XXVII | ||

| 54 | Leuye | Loei | XXVII | 16 May 1861 | |

| 55 | Paklaïe | Pak Lay | XXVII | 24 June 1861 | |

| 56 | Thodua | Tha Deua | XXVII | ||

| 57 | Luang Prabang | Luang Prabang | XXVII | 25 July 1861 | |

| 58 | Na-Lê | Na Le | XXVIII | 3 September 1861 | 15 October 1861 |

3. Angkor and Mouhot's Influence

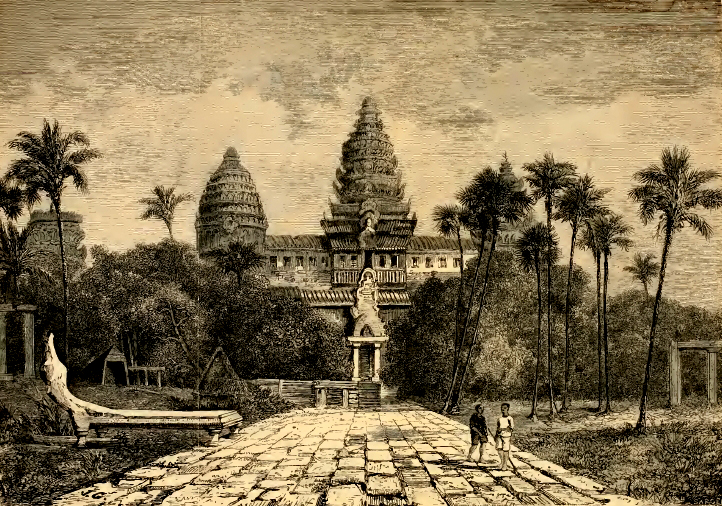

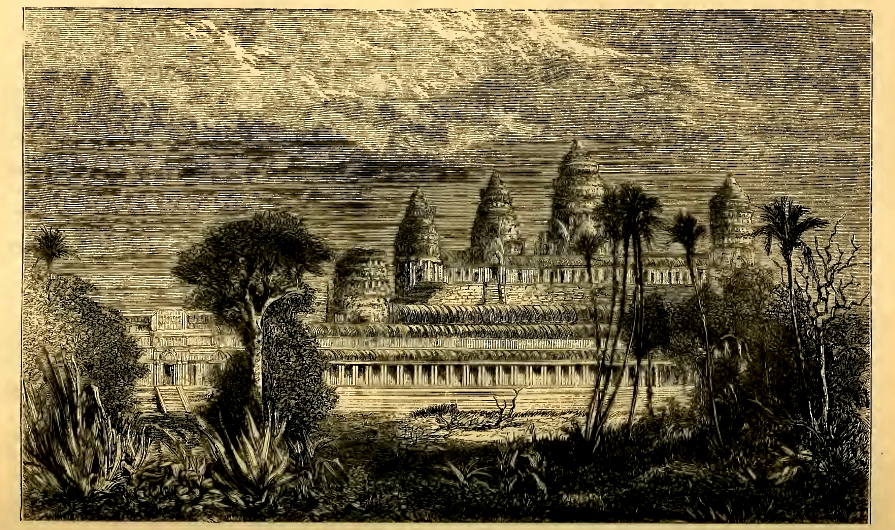

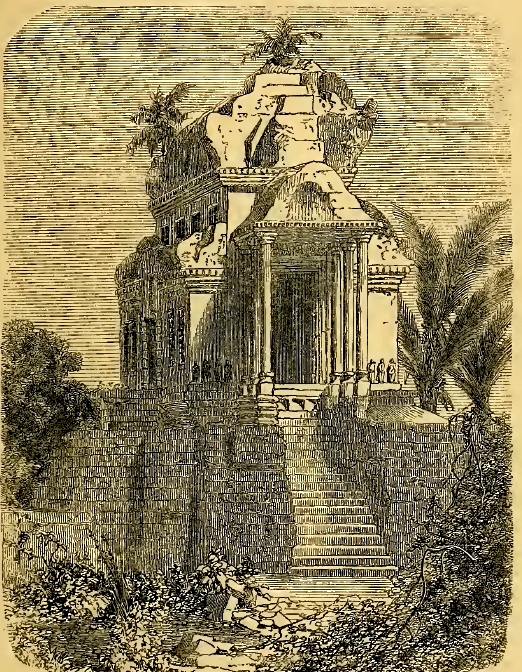

Henri Mouhot's visit to the Angkor ruins marked a pivotal moment in the Western understanding and appreciation of this ancient Khmer civilization. While often mistakenly credited with "discovering" Angkor, his detailed accounts and evocative illustrations played a crucial role in bringing the site to widespread international attention.

3.1. Visit to Angkor

Mouhot reached Angkor in January 1860, at the culmination of his second and longest journey. He spent three weeks meticulously observing and documenting the vast complex, which spanned over 154 mile2 (400 km2) and included numerous ancient terraces, pools, moated cities, palaces, and temples. Among these, Angkor Wat was the most renowned. His observations, sketches, and detailed records from this visit were later incorporated into his posthumously published travel journals, Voyage dans les royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos et autres parties centrales de l'IndochineFrench.

3.2. The "Discovery" Myth and Reality

The popular notion that Mouhot "discovered" Angkor is a misconception. The location and existence of the entire series of Angkor sites were continuously known to the Khmer people and had been visited by several Westerners long before Mouhot's arrival. For instance, a Portuguese trader, Diogo do Couto, visited Angkor and wrote about it in 1550, and the Portuguese monk António da Madalena also documented his visit to Angkor Wat in 1586. Mouhot himself noted in his journals that Father Charles Emile Bouillevaux, a French missionary based in Battambang, had reported visiting Angkor Wat and other Khmer temples at least five years prior to Mouhot's expedition, publishing his accounts in 1857 in "Travel in Indochina 1848-1846, The Annam and Cambodia". Therefore, Mouhot's contribution was not one of initial discovery, but rather of popularization.

3.3. Re-evaluation of Angkor and Western Impact

What set Mouhot apart from previous European visitors was the evocative nature of his writings and the inclusion of detailed sketches. In his posthumously published Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos, Mouhot's vivid descriptions brought Angkor to widespread Western attention. His accounts fostered significant French interest in the site, leading to subsequent efforts in its preservation and scholarly study, with France undertaking the majority of research work on Angkor for many years.

3.4. Mouhot's Interpretation of Angkor

Mouhot's interpretations of the Angkor ruins were influenced by the prevailing Western views of his time. He compared Angkor to the pyramids, reflecting a popular belief in the West that all civilization originated in the Middle East. For example, he described the Buddha heads at the gateways to Angkor Thom as "four immense heads in the Egyptian style." He further wrote of Angkor:

"One of these temples-a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michelangelo-might take an honourable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged."

Mouhot also expressed his profound admiration for the ruins, stating: "At Ongcor, there are ...ruins of such grandeur... that, at the first view, one is filled with profound admiration, and cannot but ask what has become of this powerful race, so civilized, so enlightened, the authors of these gigantic works?"

Such powerful descriptions likely contributed to the popular misconception that Mouhot had discovered the abandoned ruins of a lost civilization. The Royal Geographical Society and the Zoological Society of London, both keen to announce new findings, appeared to encourage the rumor that Mouhot, whom they had sponsored to chart mountains and rivers and catalog new species, had discovered Angkor. Mouhot himself erroneously asserted that Angkor was the work of an earlier civilization than the Khmer. Despite the very civilization that built Angkor being alive and present before his eyes, he considered them in a "state of barbarism" and could not believe they were civilized or enlightened enough to have constructed such magnificent structures. He assumed that the creators of such grandeur were a disappeared race and mistakenly dated Angkor back over two millennia, to around the same era as Rome. The true history of Angkor Wat was later pieced together from the book The Customs of Cambodia written by Zhou Daguan, an envoy of Temür Khan, who visited Cambodia in 1295-1296, and from stylistic and epigraphic evidence accumulated during subsequent clearing and restoration work carried out across the entire Angkor site. It is now known that Angkor was inhabited from the early 9th century to the early 15th century.

4. Naturalist Activities

Beyond his role as an explorer, Henri Mouhot was a dedicated naturalist. During his expeditions in Southeast Asia, he actively engaged in the collection of zoological specimens. His collections included a wide variety of insects, as well as terrestrial and river shells, which he meticulously gathered and sent back to England for study. His contributions to natural science are commemorated through the naming of two species of Asian reptiles in his honor: Cuora mouhotii, a species of turtle, and Oligodon mouhoti, a species of snake.

5. Views on Colonialism

Henri Mouhot held a nuanced perspective on European colonialism, which is evident in his writings. While some have suggested that his expeditions inadvertently served as a tool for French expansionism, leading to the annexation of territories shortly after his death, Mouhot himself did not appear to be an ardent colonialist. He occasionally expressed doubts about the beneficial effects of European colonization, questioning its ultimate impact:

"Will the present movement of the nations of Europe towards the East result in good by introducing into these lands the blessings of our civilization? Or shall we, as blind instruments of boundless ambition, come hither as a scourge, to add to their present miseries?"

Despite these reservations, Mouhot's notes reveal a genuine interest in Southeast Asia and its cultures, alongside a belief in the potential benefits that French administration could bring to these countries. He wrote in the Tour du Monde that European domination, coupled with the abolition of slavery, protective and wise laws, and honest administrators, would be capable of regenerating states like Cambodia. He envisioned such a state becoming a "granary of abundance, as fertile as lower Cochinchina," especially given France's efforts to establish itself in the region.

Mouhot observed the lack of significant production and industry in these fertile and rich regions, attributing it to the corrupt practices of kings and mandarins who enriched themselves through despoilment and abuses that hindered work and progress. He believed that if the country were administered with wisdom, prudence, loyalty, and protection for the people, "everything will change with marvellous rapidity." He also highlighted what he perceived as France's existing protective role for Cambodia, noting that without France's war against the Empire of Annam in the two years prior to his writing, the "little kingdom of Cambodia" would likely have been assimilated into neighboring peoples.

6. Death

Henri Mouhot's life of exploration came to an end on November 10, 1861, when he died of a malarial fever during his fourth expedition in the jungles of Laos. At the time, he had been visiting Luang Prabang, which was then the capital of the Lan Xang kingdom, one of three kingdoms that would eventually merge to form modern-day Laos. Mouhot was under the patronage of the king of Lan Xang at the time of his death. Two of his loyal servants buried him near a French mission in Naphan, on the banks of the Nam Khan River. Mouhot's favorite servant, Phrai, undertook the arduous task of transporting all of Mouhot's journals and collected specimens back to Bangkok, from where they were subsequently shipped to Europe.

7. Legacy and Commemoration

Henri Mouhot's work left a lasting impact, particularly in the Western world's engagement with Angkor, and his life has been commemorated through various efforts.

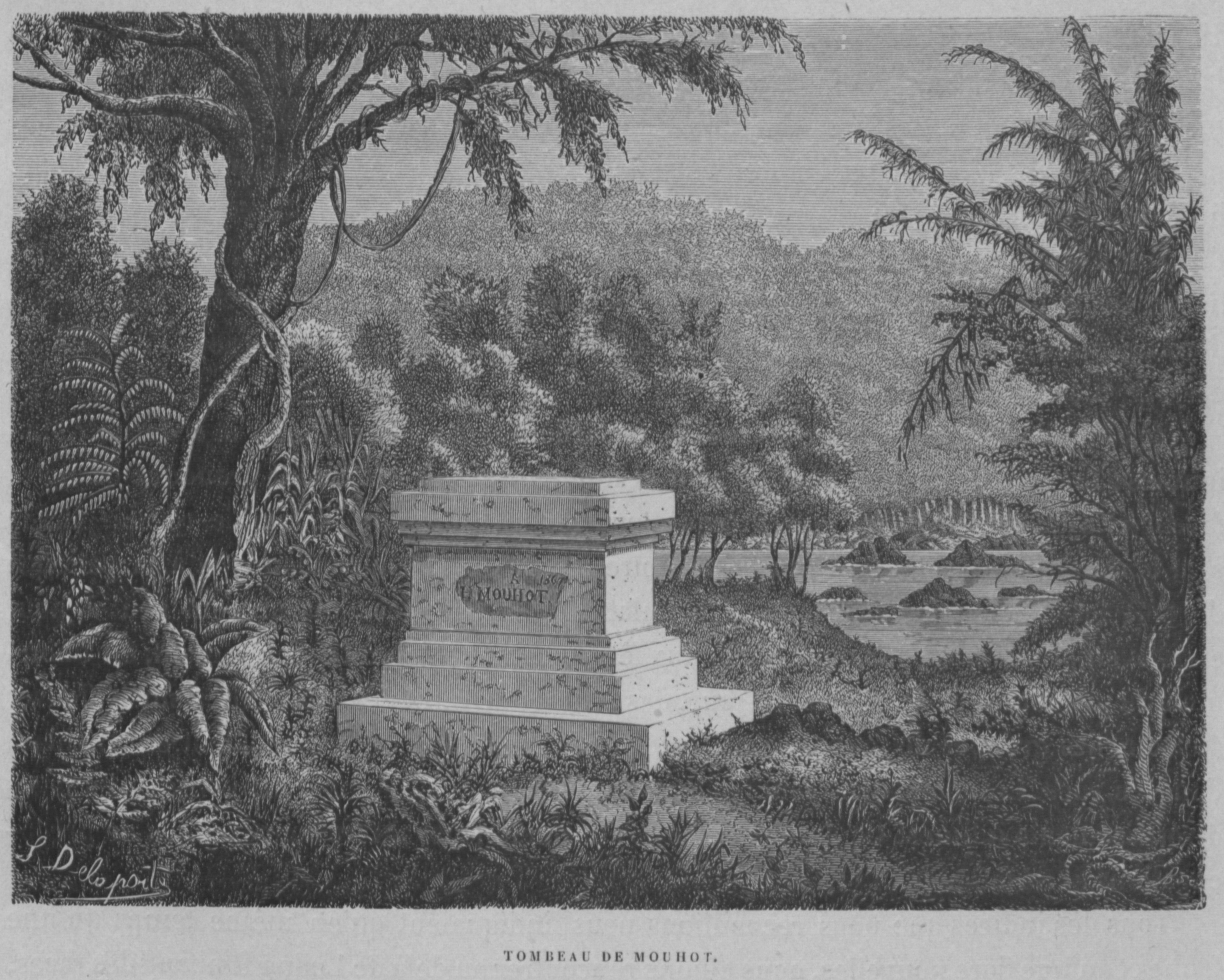

7.1. Grave and Monuments

In 1867, six years after Mouhot's death, the French commander Ernest Doudart de Lagrée, leading the Mekong Expedition of 1866-68 and acting under orders from the Governor of Cochinchina, constructed a small monument near where they believed Mouhot's grave was located. De Lagrée delivered a eulogy, stating, "We found everywhere the memory of our compatriot who, by the uprightness of his character and his natural benevolence, had acquired the regard and the affection of the natives."

Sixteen years later, when the French explorer Dr. Paul Neis traveled up the Nam Khan River, he found only "a few bricks scattered on the ground," indicating the monument had deteriorated. In 1887, Auguste Pavie arranged for a more durable crypt monument to be built, and a sala (a traditional open-sided pavilion) was constructed nearby to house and feed visitors to the white shrine. Further restoration work on the tomb was carried out in 1951 by the EFEO (French School of the Far East).

During the tumultuous years of the Second Indochina War, Mouhot's tomb was once again reclaimed by the jungle and became lost. It was not rediscovered until 1989 by French scholar Jean-Michel Strobino, working alongside Lao historian Mongkhol Sasorith. Strobino organized the monument's restoration with support from the French embassy and the Municipality of Montbéliard, Mouhot's birthplace. A new plaque was affixed to one end of the crypt in 1990 to commemorate this rediscovery. The site is now accessible to tourists and is known to hotels and tour operators in Luang Prabang. Visitors can hire a minivan or a tuk-tuk for the 6.2 mile (10 km) journey from town, followed by a walk of approximately 820 ft (250 m) down a steep track near a sharp bend on the road to Luang Prabang Railway Station, passing several small riverside restaurants before reaching the tomb.

7.2. Academic and Public Recognition

The widespread popularity of Angkor generated by Mouhot's vivid writings significantly contributed to public support for a major French role in the study and preservation of the ancient site. French scholars and institutions subsequently carried out the majority of research and conservation work on Angkor for many years. In addition to his impact on archaeology and cultural heritage, Mouhot's contributions to natural history are recognized through the naming of two species of Asian reptiles in his honor: Cuora mouhotii, a turtle, and Oligodon mouhoti, a snake.

8. Works

Henri Mouhot's travel journals are his most significant publications, providing detailed accounts and illustrations of his expeditions. His primary work is:

- Voyage dans les royaumes de Siam, de Cambodge, de Laos et autres parties centrales de l'IndochineFrench (published 1863, 1864). The English translation is titled Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China, Cambodia and Laos During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860.

Other notable publications of his work include:

- Travels in Siam, Cambodia, Laos, and Annam. Henri Mouhot

- Travels in Siam, Cambodia and Laos, 1858-1860 Henri Mouhot, Michael Smithies

- Travels in the Central Parts of Indo-China (Siam), Cambodia, and Laos During the Years 1858, 1859, and 1860. Mouhot, Henri (with black and white illustrations)

His work has also been translated into Japanese, including:

- アンコールワットの「発見」 タイ・カンボジア・ラオス諸王国遍歴記Japanese (The "Discovery" of Angkor Wat: A Journey through the Kingdoms of Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos), translated by Makoto Oiwa (2018, previously 2002).

- アンコール・ワットの発見Japanese (The Discovery of Angkor Wat), translated by Kazumasa Kikuchi (1974).

9. Related Figures and Topics

Henri Mouhot's life and work are intertwined with several key individuals and broader historical contexts that shaped 19th-century exploration and French colonialism in Southeast Asia. Notable figures include his brother Charles Mouhot, with whom he studied photography, and Louis Daguerre, whose photographic techniques influenced his early career.

His decision to explore Indochina was inspired by Sir John Bowring's writings on Siam. While Mouhot is often mistakenly credited with discovering Angkor, previous Western visitors like the Portuguese trader Diogo do Couto and the monk António da Madalena, as well as the French missionary Charles-Émile Bouillevaux, had already documented the site. The true historical understanding of Angkor was later significantly advanced by the work of Zhou Daguan, a Chinese envoy whose 13th-century account, The Customs of Cambodia, provided invaluable insights.

After Mouhot's death, French explorers such as Ernest Doudart de Lagrée, Paul Neis, and Auguste Pavie played roles in commemorating his grave and continuing French exploration efforts. Later, Jean-Michel Strobino and Mongkhol Sasorith were instrumental in rediscovering and restoring his tomb. Mouhot's expeditions occurred during a period of intense European interest in Southeast Asia, contributing to the broader narrative of 19th-century exploration and the expansion of French colonialism in the region.