1. Overview

Dona Maria Leopoldina of Austria (Maria Leopoldine Josepha Caroline von ÖsterreichMaria Leopoldine Josepha Caroline von ÖsterreichGerman; January 22, 1797 - December 11, 1826) was a prominent figure in the history of Brazil and Portugal, serving as the first Empress consort of Brazil from October 12, 1822, until her death, and briefly as Queen consort of Portugal from March 10 to May 2, 1826. Born into the powerful House of Habsburg-Lorraine in Vienna, she was the daughter of Francis II, who later became Emperor of Austria as Francis I. Her comprehensive education, encompassing arts, sciences, and politics, prepared her for a significant royal role, fostering a keen interest in natural sciences and a proficiency in seven languages.

Maria Leopoldina is widely recognized by historians as a principal architect of Brazil's independence, which occurred in 1822. Her biographer, Paulo Rezzutti, notes that she "embraced Brazil as her country, Brazilians as her people, and Independence as her cause." Her political acumen and decisive actions, particularly her role as regent and her persuasive counsel to her husband, Emperor Dom Pedro I, were crucial in shaping the nation's future. She holds the distinction of being the first woman to act as head of state in an independent American country. Beyond her political contributions, she left a lasting legacy through her patronage of scientific exploration and her advocacy for European immigration, which she promoted as a means to alleviate slavery. Despite facing personal challenges, including her husband's extramarital affairs and declining health, Maria Leopoldina earned immense popularity among the Brazilian people, who affectionately referred to her as the "Mother of Brazilians" and the "Guardian Angel of this nascent Empire."

2. Early Life and Education

Maria Leopoldina was born on January 22, 1797, at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Archduchy of Austria. She was the fifth child and fourth daughter of Francis II (who became Francis I, Emperor of Austria, in 1804), and his second wife, Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily. Her paternal grandparents were Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor and Maria Luisa of Spain, while her maternal grandparents were King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies and Maria Carolina of Austria. Through both parents, who were double first-cousins, Maria Leopoldina was a descendant of the esteemed House of Habsburg-Lorraine, one of Europe's oldest reigning dynasties, and the House of Bourbon. She was named Caroline Josepha Leopoldine Franziska Ferdinanda; the name "Maria" was not initially present in her baptismal record but she adopted it later, possibly due to her devotion to the Virgin Mary and the prevalence of the name among her sisters-in-law.

Her childhood unfolded during a tumultuous period in European history, marked by the Napoleonic Wars and the systematic reshaping of the continent's political landscape by Napoleon Bonaparte. Her elder sister, Archduchess Maria Ludovika, married Napoleon in 1810 in an attempt to strengthen ties between France and Austria, a union that deeply dismayed their maternal grandmother, Queen Maria Carolina.

Maria Leopoldina's mother died on April 13, 1807, when Leopoldina was ten years old. A year later, her father married Maria Ludovika of Austria-Este, whom Maria Leopoldina considered the most influential person in her life. Maria Ludovika, a well-educated first-cousin of her husband and granddaughter of Empress Maria Theresa, greatly influenced Maria Leopoldina's intellectual development. She instilled in her stepdaughter a love for literature, nature, and music, including works by Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven. Maria Leopoldina regarded her stepmother as her "spiritual mother" and, through her, met the renowned poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1810 and 1812.

Her upbringing adhered to three core Habsburg principles: discipline, piety, and a strong sense of duty. Her education was strict but culturally rich, shaped by the educational beliefs of her grandfather, Leopold II, who advocated for "humanity, compassion, and the desire to make people happy." This included the practice of writing texts such as: "Do not oppress the poor. Be charitable. Do not complain about what God has given you, but improve your habits. We must strive earnestly to be good." Her extensive curriculum included reading, writing, dance, drawing, painting, piano, riding, hunting, history, geography, and music, with advanced studies in mathematics, literature, physics, singing, and crafts.

From an early age, Maria Leopoldina showed a particular aptitude for the natural sciences, especially botany and mineralogy, and developed a habit of collecting coins, plants, flowers, minerals, and shells. She became a notable polyglot, mastering seven languages: her native German, as well as Portuguese, French, Italian, English, Greek, and Latin. She quickly became fluent in Portuguese by December 1816, immersing herself in maps and books about Brazil. Frequent visits to museums, botanical gardens, factories, and agricultural fields, along with participation in dances and theatrical performances, were integral to her education, preparing her for ceremonies and public exposure while developing her public speaking and oratory skills.

3. Marriage Negotiations and Arrival in Brazil

The marriage of Maria Leopoldina to Dom Pedro was a strategic political alliance between the Portuguese and Austrian monarchies, and her subsequent arduous journey to Brazil was accompanied by a significant scientific mission and marked the beginning of European immigration to the country.

For centuries, royal marriages in Europe served primarily as strategic political alliances, and the union between Maria Leopoldina and Dom Pedro de Alcântara, Prince Royal of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves, was no exception. This marriage represented a significant alliance between the monarchies of Portugal and Austria, embodying the famous Habsburg motto: Bella gerant alii, tu, felix Austria, nube ("Let others wage war, thou, happy Austria, marry").

On September 24, 1816, Emperor Francis I announced Dom Pedro de Alcântara's desire to marry a Habsburg Archduchess. Prince Klemens von Metternich specifically suggested Maria Leopoldina. The Marquis of Marialva played a crucial role in the negotiations, having previously facilitated the French Artistic Mission to Brazil. King John VI sought to include Infanta Isabel Maria of Braganza in the negotiations and secured Austrian consent by guaranteeing the Portuguese royal family's intention to return to Europe once Brazil was secure from the independence wars sweeping the Spanish colonies. The marriage contract was formally signed in Vienna on November 29, 1816.

Preparations for Maria Leopoldina's journey began in April 1817, with two frigates, Austria and Augusta, departing for Rio de Janeiro ahead of her. These ships carried furniture and decorations for the Austrian embassy, equipment for a scientific expedition into Brazil's interior, and various Austrian commercial products. During this time, Maria Leopoldina diligently studied the history and geography of her future home and quickly became fluent in Portuguese. She also meticulously compiled a unique vade mecum, a document unparalleled among Habsburg princesses.

The marriage per procuram (by proxy) between Maria Leopoldina and Dom Pedro took place on May 13, 1817, at the Augustinian Church in Vienna. Her uncle, Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen, represented the groom. Following the ceremony, a lavish reception was held at Vienna's Augarten on June 1, hosted by Marialva to showcase Portuguese splendor. This alliance allowed King John VI to counterbalance England's influence and provided Austria with a transatlantic ally aligned with the conservative, absolutist ideals of the Holy Alliance.

3.1. The Crossing of the Atlantic

Maria Leopoldina's journey to Brazil was arduous and lengthy. She departed Vienna for Florence on June 2, 1817, where she awaited further instructions from the Portuguese court, as monarchical authority in Brazil remained tenuous due to the Pernambucan revolt. On August 13, 1817, she finally set sail from Livorno, Italy, on the Portuguese fleet, comprising the ships D. João VI and São Sebastião. Accompanied by her extensive luggage and a large entourage-including court ladies, chambermaids, a butler, six ladies-in-waiting, four pages, six Hungarian nobles, six Austrian guards, six chamberlains, a chief Almoner, a chaplain, a private secretary, a doctor, a performer, a mineralogist, and her painting teacher-she endured an 86-day transatlantic crossing. Forty man-sized boxes contained her trousseau, books, collections, and gifts. She made her first stop on Portuguese territory not in Brazil, but on Madeira Island, on September 11.

Maria Leopoldina arrived in Rio de Janeiro on November 5, 1817, finally meeting her husband and his family. The official marriage ceremony was celebrated the following day at the Royal Chapel of Rio de Janeiro Cathedral, amidst city-wide festivities. Her physical appearance, though not conventionally beautiful, impressed the Portuguese royal family with her cultural depth and keen interest in botany. The artist Jean-Baptiste Debret was commissioned to decorate the city for her arrival, and he later made botanical drawings for Maria Leopoldina and designed the court's green and gold uniforms, the new state's decorations, the crown, and the insignia of the Order of the Southern Cross.

Dom Pedro, a year her junior, presented a stark contrast to the educated gentleman Maria Leopoldina had expected. His impulsive and choleric temperament, coupled with a modest education and rudimentary French, made communication difficult. He was primarily interested in horse racing and amorous affairs, living openly with the French dancer Noemie Thierry, who was removed from court by his father only after Maria Leopoldina's arrival. The young couple resided in modest rooms at the Palace of São Cristóvão, where tropical conditions made life challenging. The Baron von Eschwege, an Austrian agent, noted Pedro's lack of formal education and the uninspiring nature of the Rio court compared to European counterparts.

In the wake of Maria Leopoldina's arrival, Brazil saw its first significant wave of European immigrants. Swiss settlers established Nova Friburgo and later settled in the area of Petrópolis. From 1824, due to campaigns organized by Major Georg Anton Schäffer, German immigrants arrived in greater numbers, settling in Nova Friburgo and the southern provinces of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, where the colony of São Leopoldo was founded in Maria Leopoldina's honor. Some German-speaking Pomeranians who settled in Espírito Santo remained so isolated that they did not even speak Portuguese until the 1880s.

3.2. Austrian Scientific Mission

Brazil had a unique advantage in being studied by leading European artists and scientists long before other American nations. This began in the 17th century during the Dutch occupation of northeastern Brazil, when John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen brought experts like Willem Piso (tropical diseases), Frans Post and Albert Eckhout (painters), Cornelius Golijath (cartographer), and Georg Marggraf (astronomer) to document the region. Marggraf, along with Piso, co-authored Historia Naturalis Brasiliae (Amsterdam, 1648), the first scientific work on Brazilian nature.

Following the expulsion of the Dutch, Portugal implemented a strict policy prohibiting foreigners from accessing its overseas possessions and forbade the publication of any information about American lands. This policy persisted until the arrival of the Portuguese royal family in Brazil in 1808 and the subsequent "Decreto de Abertura dos Portos às Nações Amigas" (Decree of Opening Ports to Friendly Nations), which opened Brazil to the world.

The lifting of the ban on foreigners coincided with a difficult period for European naturalists, whose travel was hindered by the Napoleonic Wars. The vast, largely unexplored territory of Brazil thus sparked immense scientific interest in Europe. Maria Leopoldina, since her early youth, had developed a special interest in the natural sciences, particularly geology and botany. This passion, unusual for a princess, was encouraged by her father, Emperor Francis I.

In 1817, with the announcement of Maria Leopoldina's wedding to Dom Pedro, the Austrian court, in collaboration with Bavarian scientists, organized a major scientific expedition to Brazil. King Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria sent his subjects, botanist and physician Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius and zoologist Johann Baptist von Spix. Additionally, Karl von Schreibers, Director of the Natural History Museum, Vienna, under Chancellor Prince von Metternich, assembled a mission of notable scientists, including botanist and entomologist Johann Christian Mikan, physician and mineralogist Johann Emanuel Pohl, flora painter Johann Buchberger, zoologist Johann Natterer, painter Thomas Ender, gardener Heinrich Wilhelm Schott, and Italian naturalist Giuseppe Raddi. Their objective was to collect specimens and create illustrations of Brazilian people and landscapes for a museum in Vienna.

The expedition's primary interest was to document the New World by researching its plants, animals, and indigenous populations. This fascination was fueled by the publication of the first volume of Le voyage aux régions equinoxiales du Nouveau Continent, fait en 1799-1804 by German geographer Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt's work, which presented an encyclopedic view of his observations, greatly influenced artists like Johann Moritz Rugendas.

Maria Leopoldina's scientific interests continued after her arrival in Brazil. In 1818, she influenced her father-in-law to establish the Royal Museum, now the National Museum of Brazil, and contributed to the creation of the first Brazilian Natural History Museum, which promoted scientific exploration. In September 1824, the British writer Maria Graham arrived in Brazil and was warmly received by Dom Pedro and Maria Leopoldina. Graham was appointed governess to their eldest daughter, Maria da Glória, whose education had been neglected. Maria Leopoldina and Maria Graham quickly developed an affectionate friendship, bonded by their shared interest in the sciences. Although Dom Pedro dismissed Maria Graham after only six weeks, to Maria Leopoldina's dismay, their shared intellectual curiosity allowed them to remain close friends until Maria Leopoldina's death, as they sought knowledge not readily available to women in their male-dominated world.

4. Role in Brazilian Independence Movement

Maria Leopoldina's political acumen and unwavering commitment were crucial in shaping Brazil's path to independence, particularly through her decisive actions as regent and her influence on Dom Pedro during critical junctures.

The year 1821 proved pivotal in Maria Leopoldina's life. Though educated within the conservative traditions of the Habsburg dynasty and the absolutist monarchies of Europe, she began to adapt her political views. In June 1821, she wrote to her father, expressing suspicion about "new ideas" embraced by her husband, referring to the burgeoning constitutional and liberal political values spreading across Europe. Having witnessed firsthand Napoleon Bonaparte's systematic alteration of political power, she initially held a conservative and traditional outlook.

However, Maria Leopoldina, who had previously felt a lack of affection and approval, quickly matured into a resolute woman. As tensions between Portugal and Brazil escalated, she became increasingly immersed in the political turmoil preceding Brazil's independence. Her involvement with Brazilian politics, alongside figures like José Bonifácio de Andrada, proved fundamental. During this phase, she distanced herself from the conservative, absolutist ideas of the Vienna court and adopted a more liberal, constitutional stance, aligning herself with the Brazilian cause.

The Liberal Revolution of 1820 in Portugal forced the Portuguese court, including King John VI, to return to Portugal on April 25, 1821. Dom Pedro remained in Brazil as regent, granted extensive powers counterbalanced by a regency council. Initially, Dom Pedro struggled to control the anarchic situation, dominated by Portuguese troops. The growing antagonism between Portuguese and Brazilians became evident, and Maria Leopoldina's correspondence clearly shows her warm embrace of the Brazilian people's cause and her increasing desire for the country's independence.

4.1. The Conspirator of São Cristóvão

Maria Leopoldina grew up with a profound fear of popular revolutions, largely influenced by the fate of her great-aunt, Marie Antoinette, who was guillotined during the French Revolution. However, the Brazilian independence movement differed significantly; rather than threatening monarchical power, it surprisingly positioned Dom Pedro and Maria Leopoldina as protagonists. Brazilians, for the first time, saw them as allies rather than tyrants to be overthrown.

Despite her upbringing in a strict absolutist regime, Maria Leopoldina did not foresee her role as regent during the tumultuous period before the break with Portugal, nor her eventual defense of Brazilian independence-a stance directly contrary to her traditional education. She consistently sided with the Brazilian cause, frequently distinguishing between Portuguese and Brazilians in her letters to European friends, making clear her views on Portuguese domination. With the court's return to Portugal and Dom Pedro's appointment as Prince Regent of Brazil (April 25, 1821), Maria Leopoldina became convinced that remaining in America was essential to defending dynastic legitimacy against the liberal excesses threatening the power of the Habsburg and Bragança houses in Brazil. Dom Pedro, lacking political experience and overwhelmed by the instability, repeatedly asked his father to release him from the regency and allow his family's return to Portugal.

Maria Leopoldina's resolve to stay intensified with the support of José Bonifácio de Andrada, an educated statesman from São Paulo. With his help, she decisively persuaded her husband that preserving Brazil's territorial integrity depended on their continued presence. Consequently, on January 9, 1822, Dom Pedro famously declared: "Fico!" (I am staying!Portuguese). At 24 years old, Maria Leopoldina's political decision committed her to an indefinite stay in America, forever depriving her of living near her immediate family in Europe. Much like her sister Marie Louise married Napoleon Bonaparte to foster Franco-Austrian relations, Maria Leopoldina's role in history proved even more profound.

Two days after Dom Pedro's "Dia do Fico", the decision of the Prince-Regent to remain in Brazil sparked outrage among the Portuguese Cortes (parliamentary representatives), who desired the royal family's departure and Brazil's fragmentation. Government offices were burned, and a revolution erupted. While Dom Pedro confronted the Cortes with his troops, Maria Leopoldina appeared on stage at the theatre and declared: "Remain calm, my husband has everything under control!" This announcement, met with jubilation, solidified her alignment with the Brazilian people.

However, Maria Leopoldina recognized the danger to her life. Seven months pregnant, she quickly fled to Santa Cruz with her three-year-old daughter Maria da Glória and eleven-month-old son João Carlos, undertaking a perilous twelve-hour journey. Though the political situation soon stabilized, and she returned to Boa Vista, her young son João Carlos tragically died on February 4, 1822, likely due to the strain. By the end of 1821, Maria Leopoldina's letters, such as one to her secretary Schäffer, reveal her greater determination for Brazil's cause than Dom Pedro's, advocating defiance of the Portuguese court. Her "Dia do Fico" effectively preceded her husband's.

On August 6, 1822, Dom Pedro signed the Manifesto to the Friendly Nations, denouncing the despotism of the Lisbon courts and urging other nations to deal directly with Rio de Janeiro rather than the Portuguese government. While the document explained Brazil's cause from a Brazilian perspective, it still indicated Dom Pedro's reluctance to fully sever ties, a neutrality Maria Leopoldina recognized as ineffective. Despite women's limited political roles, Maria Leopoldina strategically offered "specific advice and influencing others to her husband," achieving her objectives. Dom Pedro initially sought neutrality to avoid losing his inheritance to the Portuguese throne. Maria Leopoldina, however, understood that Portugal, dominated by its courts, was already lost, while Brazil remained a blank canvas with the potential to become a powerful nation, far more significant than the old metropolis. She foresaw that if Lisbon's orders were enforced, Brazil would fragment into dozens of republics, mirroring the fate of the Spanish colonies in South America.

Maria Leopoldina's unwavering defense of Brazilian interests is powerfully conveyed in a letter she wrote to Dom Pedro during the lead-up to independence: "You need to come back as soon as possible. Be persuaded that it is not only love that makes me want your immediate presence more than ever, but the circumstances in which the beloved Brazil is. Only your presence, a lot of energy and rigor can save you from ruin." In Rio de Janeiro, thousands of signatures were collected, demanding the regents' continued presence in Brazil. Following the "Dia do Fico", a new ministry was formed under the leadership of José Bonifácio, a staunch monarchist, and the Prince-Regent quickly gained public trust. On February 15, 1822, Portuguese troops departed Rio de Janeiro, symbolizing the dissolution of ties with the metropolis. Dom Pedro was triumphantly received in Minas Gerais.

4.2. Regency

When her husband traveled to São Paulo in August 1822 to stabilize the political situation, Maria Leopoldina was appointed his official representative and acting Regent. Her authority was formalized through an investiture document dated August 13, 1822, which named her head of the Council of State and Acting Princess-Regent of the Kingdom of Brazil, granting her full power to make necessary political decisions during his absence. Her influence on the independence process was immense. Brazilians were keenly aware of Portugal's intention to recall Dom Pedro, effectively reducing Brazil to a mere colony rather than a kingdom united with Portugal. Fears of a civil war separating the Province of São Paulo from the rest of Brazil were prevalent.

A new decree from Lisbon, containing further demands, reached Rio de Janeiro. Without time to await Dom Pedro's return, Maria Leopoldina, advised by José Bonifácio de Andrada and exercising her authority as interim head of government, convened the Council of State on the morning of September 2, 1822. She then signed the Decree of Independence, officially declaring Brazil separate from Portugal. Maria Leopoldina sent a letter to Dom Pedro, along with a letter from José Bonifácio and critical comments from Portugal regarding her husband's actions. In her letter, the Princess-Regent urged her husband to proclaim Brazil's independence with the urgent warning: "O pomo está maduro, colha-o já, senão apodrecePortuguese" (The fruit is ripe, pick it up now, or it will rotEnglish).

Dom Pedro declared the Independence of Brazil on September 7, 1822, in São Paulo, upon receiving his wife's letter. Maria Leopoldina had also forwarded papers from Lisbon and comments from Antônio Carlos Ribeiro de Andrada, a deputy to the Portuguese courts, informing the Prince-Regent of the metropolis's criticisms. The position of John VI and his ministry, controlled by the courts, was precarious. While awaiting her husband's return, Maria Leopoldina, now the interim ruler of an independent country, conceptualized the design for the new flag of Brazil. She combined the green of the House of Braganza with the golden yellow of the House of Habsburg. Some sources also attribute elements of the design to Jean-Baptiste Debret, working in collaboration with José Bonifácio de Andrada, with the green rectangle representing Brazil's forests and the yellow rhombus symbolizing the gold of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty. Subsequently, Maria Leopoldina dedicated herself to securing international recognition for the new nation's autonomy, writing letters to her father, the Emperor of Austria, and her father-in-law, the King of Portugal.

Maria Leopoldina became Brazil's first Empress consort, officially acclaimed as such on December 1, 1822, during the coronation ceremony and consecration of her husband as Dom Pedro I, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil. Due to Brazil's status as the sole monarchy in South America at the time, Maria Leopoldina held the unique position of being the first Empress of the New World.

4.3. Bahia's Participation in the Independence Process

Bahia, once the initial seat of government, a radiating center for metropolitan policies, and a strategic port, lost its privileged status with the discovery of gold in the Hereditary Captaincy of Espírito Santo. The region where the gold deposits were found by Bandeirantes was dismembered and transformed into the province of Minas Gerais, a process that repeated as new deposits emerged, shrinking the Captaincy of Espírito Santo and creating an ill-fated barrier against gold smuggling. This eventually led to the transfer of the capital to Rio de Janeiro in 1776. Salvador initially resisted the permanent relocation of the court in 1808.

During Brazil's separation from Portugal, Bahia harbored opposing factions: a pro-independence interior and a capital loyal to the Lisbon court. After September 7, 1822, an armed struggle ensued, culminating in victory for the imperial troops on July 2, 1823. Bahian women actively participated in this patriotic conflict. Maria Quitéria, who clandestinely enlisted as a soldier loyal to the Brazilian cause, was later described by Maria Graham and decorated by the Order of the Southern Cross by Emperor Pedro I. The oral tradition of Itaparica Island also credits Afro-Brazilian Maria Felipa de Oliveira with leading over 40 black women in defending the island. Sister Joana Angélica, Abbess of the Convent of Lapa, gave her life to prevent Portuguese troops from entering the cloister.

The political awareness of women was further highlighted in the "Carta das senhoras baianas à sua alteza real dona LeopoldinaPortuguese" (Letter from the Bahian ladies to Her Royal Highness Dona Leopoldina), which congratulated the Princess-Regent for her crucial role in patriotic resolutions on behalf of her husband and the country. This letter, signed by 186 Bahian ladies and delivered in August 1822, expressed their profound gratitude for Maria Leopoldina's decision to remain in Brazil. Maria Leopoldina herself commented on women's political engagement in a letter to her husband, noting that the ladies' attitude "proves that women are more cheerful and are more adherent to the good cause." Despite not resuming its role as the governmental headquarters, Bahia played a significant part in the regional political balance that favored the Brazilian Empire. In recognition of this support, the Emperor and Empress visited Salvador between February and March 1826.

5. Empress of Brazil and Queen of Portugal

Maria Leopoldina became Brazil's first Empress consort, a title she received upon her husband's acclamation as Dom Pedro I, Constitutional Emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil, on December 1, 1822. Her position was unique as she was the first and only Empress of the New World at the time, a testament to Brazil's pioneering status as the sole monarchy in South America.

Her role briefly expanded when King John VI of Portugal died on March 10, 1826. Consequently, Dom Pedro inherited the Portuguese throne as King Pedro IV, making Maria Leopoldina both Empress consort of Brazil and Queen consort of Portugal. However, recognizing that a reunion of Brazil and Portugal would be politically untenable for the people of both nations, Dom Pedro hastily abdicated the Portuguese crown less than two months later, on May 2, in favor of their eldest daughter, Maria da Glória, who became Queen Dona Maria II. Thus, Maria Leopoldina's tenure as Queen of Portugal was short-lived, solidifying her primary identity as Empress of Brazil.

6. Personal Life and Family

Maria Leopoldina's personal life was marked by her deep commitment to her role as Empress and mother, alongside significant challenges arising from her husband's behavior. Her relationship with Emperor Pedro I became increasingly strained and overshadowed by his scandalous affair with Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo, Marchioness of Santos. This affair caused Maria Leopoldina profound humiliation, morally and psychologically. Dom Pedro publicly recognized his illegitimate daughter with Domitila, Isabel Maria de Alcântara Brasileira, born in May 1824, granting her the title of Duchess of Goiás with the style of Highness and the honorific "Dona." Adding to her distress, his mistress was even appointed as a lady-in-waiting to the Empress. Maria Leopoldina expressed her despair in a letter to her sister Marie Louise, stating: "The seductive monster is the cause of all my misfortunes."

Isolated and increasingly depressed, Maria Leopoldina focused primarily on her duty to provide an heir to the House of Braganza. Her pregnancies were frequent and often difficult, including several miscarriages.

Her children with Emperor Pedro I were:

- Maria da Glória (born April 4, 1819), later Queen of Portugal.

- A miscarriage in November 1819.

- A second miscarriage on April 26, 1820, a son named Miguel.

- João Carlos, Prince of Beira (born March 6, 1821), her first living son.

- Januária (born March 11, 1822).

- Paula (born February 17, 1823).

- Francisca (born August 2, 1824).

- Pedro, the long-awaited male heir (born December 2, 1825), who would become the future Emperor of Brazil.

Her ninth and final pregnancy tragically resulted in a miscarriage that proved fatal.

7. Health Decline and Death

Maria Leopoldina's final months were marked by a rapid decline in health, exacerbated by personal distress and culminating in her death, a period met with profound public grief and lasting historical debate regarding its precise cause.

7.1. Popular Commotion

Maria Leopoldina was immensely loved by the Brazilian people, and her popularity surpassed that of Dom Pedro. As her health declined rapidly in November 1826, marked by cramps, vomiting, bleeding, and delusions, worsened by a new pregnancy, Rio de Janeiro closely monitored her condition. The ambassador of the Kingdom of Prussia, Theremim, reported the widespread public demonstrations of affection for the Empress to the court of Berlin: "The consternation among the people was indescribable; never [...] has such an unanimous feeling been seen. The people were literally on their knees pleading with the Almighty for the preservation of the Empress, the churches were not empty and in the domestic chapels everyone was on their knees, the men formed processions, not of habitual ones that almost usually provoke laughter, but of true devotion. In a word, such unexpected affection, manifested without dissimulation, must have been a real satisfaction for the sick Empress."

On December 7, 1826, the Diário Fluminense reported the ongoing anxiety of the people of Rio de Janeiro, who ceaselessly sought news of the Empress's "afflictive state." The newspaper described crowds, rich and poor, nationals and foreigners, gathering with tears and downcast faces, all asking: "How is the Empress?" On the afternoon of December 6, numerous processions, carrying "the Sacred Images of the respective churches," proceeded to the Imperial Chapel. Father Sampaio, the official preacher, remarked: "Never was observed on the entrance of São Cristóvão such amount of people; the carriages were run over; everyone ran in tears, however, that in the city center the prayer processions revolved, with their images, and with the accompaniment of the whole clergy, either regular or secular. The people cannot see without public signs of piety the image of Nossa Senhora da Glória, who never left her temple, and who, for the first time, under a lot of rain, went like visiting the Empress, who appeared every Saturday at the feet of its altars...There was, in a word, no brotherhood that did not take the saints of the greatest devotion to the Imperial Chapel."

7.2. Cause of Death

The precise cause of Maria Leopoldina's death remains a subject of historical debate. Some authors attribute her passing to puerperal sepsis, particularly as the Emperor was away in Rio Grande do Sul inspecting troops during the Cisplatine War.

A widely propagated theory, supported by historians such as Gabriac, Carl Seidler, John Armitage, and Isabel Lustosa, suggests that Maria Leopoldina died as a direct result of physical assaults during a violent tantrum by her husband. This alleged incident occurred on November 20, 1826, when Maria Leopoldina was preparing to assume the regency while Dom Pedro traveled south for the war. To dispel rumors of his extramarital affairs and marital discord, Dom Pedro I planned a large farewell reception, demanding that both the Empress and his mistress, the Marchioness of Santos, appear together for the protocolary hand-kissing ceremony. Maria Leopoldina, refusing to officially acknowledge her husband's mistress, defied his orders and refused to attend. The Emperor, known for his volatile temper, reportedly had a bitter argument with his wife, allegedly dragging her around the palace and attacking her with words and kicks. He then attended the reception solely with the Marchioness of Santos before departing for the war. The only witnesses to this aggression were the three individuals involved, and suspicions regarding the assault were raised by the ladies-in-waiting and doctors who attended to Maria Leopoldina afterward. However, some argue that the accounts were exaggerated, with historian Pedro Calmon stating: "It was exaggerated, that Dom Pedro had kicked her, and this was the reason for her illness. The scene, witnessed by the Austrian agent [referring to Baron Philipp Leopold Wenzel von Mareschal], consisted of wild words. Maria Leopoldina lacked reasons for the disturbance of pregnancy, the failure of which she succumbed."

The Empress, who had suffered from severe depression for months and was in the twelfth week of pregnancy, experienced a profound deterioration in her health. It was reported that she dictated a final letter to her sister Marie Louise, in which she mentioned the "terrible attack" she had suffered from her husband in the presence of his mistress. However, recent studies, particularly by Paulo Rezzutti, suggest this letter may be a fabrication. The original French version has never been found, and the Portuguese copy, preserved in the Imperial Museum in Petrópolis, only surfaced on August 5, 1834, nearly eight years after her death, with witnesses who were significantly indebted to Maria Leopoldina.

New forensic analysis conducted between March and August 2012 by coroner Luiz Roberto Fontes provides an alternative explanation. Fontes stated that a "serious illness" caused Maria Leopoldina's miscarriage and subsequent death, dismissing the theory of a physical altercation. Tomography revealed no bone fractures, ruling out legends of falls or direct assault. According to Fontes, the first threat of miscarriage occurred on November 19, with a small bleed. Her condition worsened with fever and severe diarrhea, indicative of a dangerous intestinal hemorrhage for a pregnant woman. On November 30, she began experiencing delusions. Medical records show she miscarried a male fetus of about three months' gestation on December 2, days before her death. Even after the miscarriage, her health continued to decline with increasing delusions, fever, and hemorrhages, leading to a "clear septic picture, a picture of death."

7.3. Death and Preservation of Memory

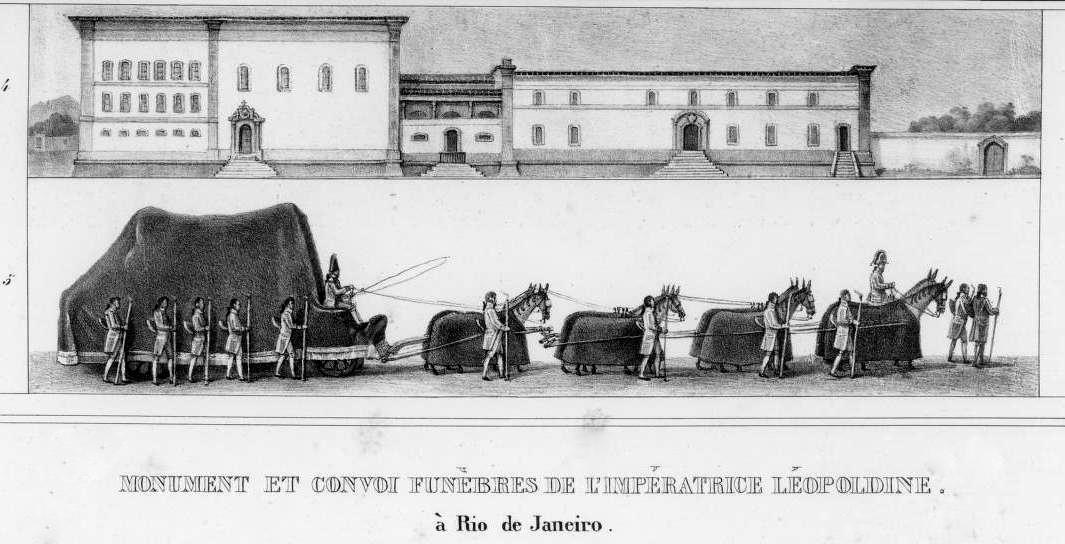

Maria Leopoldina died at the São Cristóvão Palace within the Quinta da Boa Vista, in the São Cristóvão neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, on December 11, 1826, just five weeks before her 30th birthday. Her funeral ceremony was presided over by Francisco do Monte Alverne, the official preacher of the Empire of Brazil. Her body, draped in the imperial mantle, was placed within three nested urns: the first of Portuguese pine, the second of lead (inscribed in Latin with a skull and crossed tibias, bearing the imperial silver coat), and the third of cedar.

She was initially buried on December 14, 1826, in the church of the Ajuda Convent, located in what is now Cinelândia. When the convent was demolished in 1911, her remains were transferred to the Santo Antônio Convent, also in Rio de Janeiro, where a mausoleum was built for her and other members of the imperial family. In 1954, her remains were definitively reinterred in a green granite sarcophagus adorned with gold, located in the Imperial Crypt and Chapel beneath the Ipiranga Monument in São Paulo.

During Maria Leopoldina's agony, various rumors circulated, including that she was imprisoned at the Quinta da Boa Vista or being poisoned by her doctor at the behest of the Marchioness of Santos. Domitila de Castro's already low popularity plummeted, leading to her house in São Cristóvão being stoned and her brother-in-law, a butler to the Empress, being shot twice. The Marchioness's right to attend the Empress's medical appointments, in her capacity as lady-in-waiting, was revoked, and palace officials advised her to cease attending court. The official statement issued to the Emperor on December 11 regarding his wife's death reported seizures, high fever, and delusions. Enjoying immense popular appreciation, Maria Leopoldina's death was widely mourned across the nation. Her passing significantly contributed to the decline in Dom Pedro I's popularity, compounding the problems of his reign. The writer and biographer Carlos H. Oberacker Júnior noted that "rarely has a foreigner been so dear and recognized by a people like her."

This version of events, particularly the rumors of abuse, spread to Europe and severely tarnished Dom Pedro I's reputation, making his subsequent attempts at a second marriage very difficult. It is said that Francis I of Austria, the first recipient of the Imperial Order of Dom Pedro I, received the decoration as an apology from his son-in-law, the Brazilian Emperor.

8. Legacy and Influence

While often historically portrayed as a melancholic woman humiliated by Dom Pedro I's scandals and extramarital affairs, recent historiography has asserted a more active and influential image for Maria Leopoldina in Brazilian national history. She played a significant political role in Brazil, both during the Portuguese court's return to Portugal and behind the scenes of the escalating tensions between Brazil and Portugal leading up to independence in 1822. Even as Dom Pedro I considered maintaining the United Kingdom with Portugal, Maria Leopoldina had already concluded that the most prudent path was Brazil's complete emancipation from the metropolis.

Her rigorous intellectual and political education, coupled with a strong sense of duty and sacrifice for the State, proved fundamental for Brazil, especially after King John VI was compelled to return to Lisbon under Portuguese pressure following the Liberal Revolution of 1820. Despite being an Archduchess of Austria, a member of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, and educated under an aristocratic and absolutist regime, Maria Leopoldina championed more representative forms of government for Brazil, influenced by principles of liberalism and constitutionalism.

Maria Leopoldina garnered immense respect and admiration from the Brazilian populace from the moment she arrived. She was exceptionally popular, especially among the poor and enslaved populations, who, upon her death, lamented with cries of: "Our mother died. What will become of us? Who will take sides with blacks?" Following her passing, petitions were made for the Empress to receive the title of "Guardian Angel of this nascent Empire," and she began to be affectionately called the "Mother of Brazilians." During her final illness, processions filled the streets of Rio de Janeiro, and churches and chapels overflowed with grieving people. The news of her death caused a profound stir across the city. Her popularity stood in stark contrast to Dom Pedro I's, whose public support declined considerably after her death, exacerbated by the problems of his reign. Carlos H. Oberacker Júnior, her biographer, remarked that "rarely has a foreigner been so dear and recognized by a people like her."

During her life, Maria Leopoldina actively sought ways to end slavery. In an effort to change the labor system in Brazil, she strongly encouraged European immigration to the country. Her arrival in Brazil directly fostered the beginning of German immigration, initially with Swiss settlers establishing Nova Friburgo in Rio de Janeiro. Subsequently, she encouraged Germans to populate southern Brazil. Maria Leopoldina's presence in South America served as effective "propaganda" for Brazil within Germanic circles.

Her significance on Brazilian soil is also attributed to the scientific mission that accompanied her from the Italian Peninsula, composed of European painters, scientists, and botanists. Given her personal interest in botany and geology, two notable German scientists, botanist Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius and zoologist Johann Baptist von Spix, accompanied her, along with the traveling painter Thomas Ender. The extensive research conducted by this mission resulted in groundbreaking works such as Viagem pelo Brasil and Flora Brasiliensis, a comprehensive compendium of approximately 20,000 pages that classified and illustrated thousands of native plant species. Together, these scientists journeyed over 6.2 K mile (10.00 K km) from Rio de Janeiro to the borders of Peru and Colombia.

Maria Leopoldina's steadfast refusal to return to Portugal remains a point of academic discussion. While some historians view her stance as a revolutionary act, others consider her primarily a strategist. Maria Celi Chaves Vasconcelos, a professor at UERJ specializing in the education of noblewomen, finds no evidence of rebellion in Maria Leopoldina's writings, suggesting her influence on the Proclamation of Independence stemmed from her deep knowledge of political history and her astute judgment of the opportune moment for independence. However, historian Paulo Rezzutti argues that regardless of her motivations, Maria Leopoldina must be interpreted as a revolutionary woman for being the first to engage in high-level political decision-making in Brazil. Her name is honored through the municipality of Santa Leopoldina and the palm genus Leopoldinia.

9. Depictions in Culture

Empress Maria Leopoldina's life and legacy have been frequently portrayed in various cultural mediums, cementing her place in popular historical narratives.

- Film:** She was played by Kate Hansen in the 1972 film Independência ou Morte.

- Television:** Maria Padilha depicted her in the 1984 miniseries Marquesa de Santos, Érika Evantini in the 2002 miniseries O Quinto dos Infernos, and Letícia Colin in the 2017 telenovela Novo Mundo.

- Samba Schools:** Her life indirectly inspired the name of the samba school Imperatriz Leopoldinense, which is based in the area of the Leopoldina Railway, named in her honor. In 1996, the school's carnival plot honored her, with support from the Austrian government. In 2018, both Maria Leopoldina and Imperatriz Leopoldinense were honored by the Tom Maior samba school at the São Paulo carnival.

- Musical Theater:** In 2007, actress Ester Elias portrayed Maria Leopoldina in the musical Império, by Miguel Falabella, which chronicles parts of the Empire of Brazil's history.

10. Titles and Honors

Maria Leopoldina held numerous significant royal titles and honors throughout her life:

- Dame Grand Mistress of the Order of Saint Isabel (United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves)

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa (United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves)

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I (Empire of Brazil)

- Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the Southern Cross (Empire of Brazil)

- Dame of the Order of the Starry Cross (Austrian Empire)

- Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa (Kingdom of Spain)

- Dame of the Order of Saint Elizabeth (Kingdom of Bavaria)

11. Children

Maria Leopoldina and Emperor Pedro I had seven children, all of whom played significant roles in the royal houses of Portugal and Brazil.

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maria II of Portugal |  | April 4, 1819 - November 15, 1853 | Queen of Portugal from 1826 until 1853. Maria II's first husband, Auguste de Beauharnais, 2nd Duke of Leuchtenberg, died a few months after their marriage. Her second husband was Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who became King Dom Fernando II after the birth of their first child. She had eleven children from this second marriage. Maria II was heiress presumptive to her brother Pedro II as Princess Imperial until her exclusion from the Brazilian line of succession by law no. 91 of October 30, 1835. |

| Miguel, Prince of Beira | April 26, 1820 | Prince of Beira from birth to his death, which occurred on the same day. | |

| João Carlos, Prince of Beira | March 6, 1821 - February 4, 1822 | Prince of Beira from birth to his death at 11 months old. | |

| Princess Januária of Brazil |  | March 11, 1822 - March 13, 1901 | Married Prince Luigi, Count of Aquila, son of Don Francesco I, King of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. She had four children from this marriage. Officially recognized as an Infanta of Portugal on June 4, 1822, she was later considered excluded from the Portuguese line of succession after Brazil became independent. |

| Princess Paula of Brazil |  | February 17, 1823 - January 16, 1833 | She died at the age of 9, probably of meningitis. Born in Brazil after its independence, Paula was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession. |

| Princess Francisca of Brazil |  | August 2, 1824 - March 27, 1898 | Married Prince François, Prince of Joinville, son of Louis Philippe I, King of the French. She had three children from this marriage. Born in Brazil after its independence, Francisca was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession. |

| Pedro II of Brazil |  | December 2, 1825 - December 5, 1891 | Emperor of Brazil from 1831 until 1889. He was married to Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies, daughter of Don Francesco I, King of the Two Sicilies. He had four children from this marriage. Born in Brazil after its independence, Pedro II was excluded from the Portuguese line of succession and did not become King Dom Pedro V of Portugal upon his father's abdication. |

12. Ancestry

Maria Leopoldina of Austria was born into a distinguished lineage, connecting her to some of Europe's most prominent royal houses. Her parents were Francis II, who also reigned as Emperor of Austria as Francis I, and Maria Theresa of Naples and Sicily.

Her paternal grandparents were Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor, and Maria Luisa of Spain. Leopold II was the son of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, and Maria Theresa of Austria, who was the renowned Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary and Bohemia. Maria Luisa of Spain was a daughter of Charles III of Spain and Maria Amalia of Saxony.

On her maternal side, her grandparents were King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies (also King Ferdinand IV & III of Naples and Sicily) and Maria Carolina of Austria. Ferdinand I was also a son of Charles III of Spain and Maria Amalia of Saxony, making Maria Leopoldina's parents double first-cousins. Maria Carolina of Austria was a daughter of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, and Maria Theresa of Austria.

This intricate web of marriages meant Maria Leopoldina was descended from both the ancient House of Habsburg-Lorraine and the House of Bourbon, ensuring her strong ties to the ruling dynasties across Europe.