1. Early Life and Education

Chung Il-kwon's early life was shaped by the geopolitical complexities of Northeast Asia in the early 20th century, marked by poverty and a diverse educational background that included military training under Japanese influence.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Chung Il-kwon was born on November 21, 1917, in Ussuriysk, Primorsky Krai, Russia, then part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. His father, Jeong Gi-yeong (정기영Korean), a native of Kyongwon County, North Hamgyong Province (then part of Korea under Japanese rule), worked as an interpreter for the Imperial Russian Army. His mother was Kim Sun-bok (김순복Korean), originally named Kim Bok-sun (김복순Korean). The family's ancestral seat was Yeonggwang. Chung was the third son, but his two elder brothers died young, making him effectively the sole male heir. Following the October Revolution in 1917, his father was dismissed from the Russian military and the family returned to Kyongwon County in Korea in 1922, escaping the turmoil in Russia. However, in 1928, their cultivated land was confiscated under the pretext that his father was a "disloyal Korean," forcing the family to relocate to the Tumen River area and clear wasteland, plunging them into extreme poverty.

1.2. Childhood and Education in Manchuria

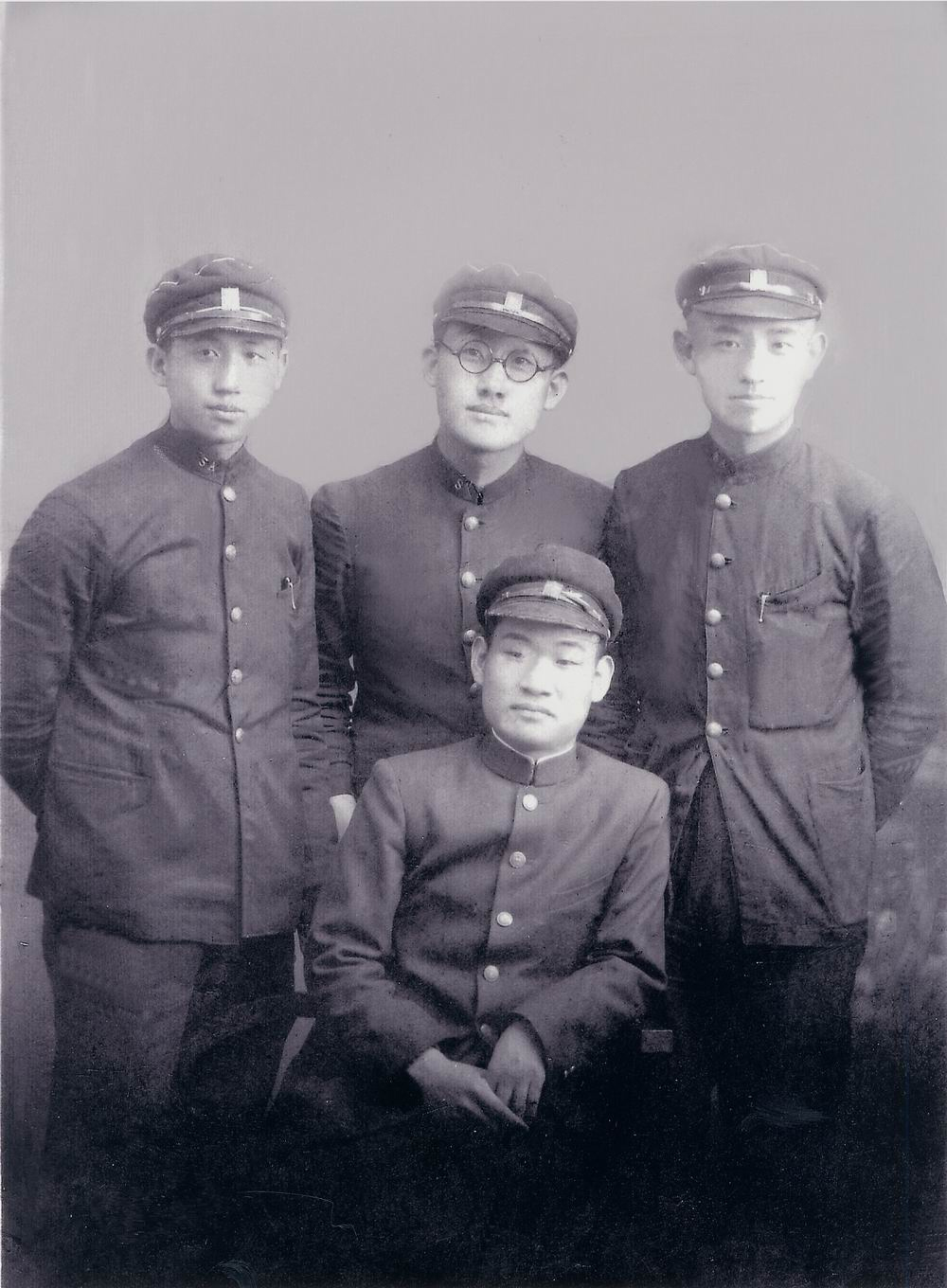

In 1930, his family moved to what is now Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Manchuria, where Chung grew up in extreme poverty. He attended Kyongwon Ordinary School in North Hamgyong Province from 1924. In 1930, he entered Yeongsin Middle School in Longjing, North Gando, Manchuria. During this period, he supported himself by selling newspapers, delivering milk, and carrying water for Japanese households. In 1934, Yeongsin Middle School merged into Gwangmyeong Middle School, from which he graduated the following year. During his time at Gwangmyeong Middle School, he befriended notable figures who would later become prominent social activists and intellectuals, including Jang Jun-ha, Mun Ik-hwan, and the anti-Japanese poet Yun Dong-ju.

1.3. Military Education

Due to his excellent academic performance, Chung was recommended by his English teacher and military instructor to enroll in the Manchukuo Imperial Army's primary officer training institution, the Central Military Training Academy (also known as Fengtian Military Academy). He was admitted in May 1935 and graduated as the top student of its 5th class in September 1937. As a top graduate, he was recommended for further study at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in Tokyo, following his classmate Kim Seok-beom. He specialized in cavalry operations and underwent a year-long cavalry training course at the Manchukuo Army Cavalry Training Center. He formally entered the Japanese Army Academy in 1939 and graduated from its 55th class (cavalry equivalent) in 1940. He also attended the Manchukuo Army Higher Military School in Xinjing (Changchun), established in 1943, as the only Korean among 25 successful candidates for its second class in 1944. His studies there were cut short by the end of the Pacific War.

After the liberation of Korea, he enrolled in the Military English School (1st class) in December 1945, graduating in January 1946. He later pursued further military education at the United States Army Command and General Staff College in 1951. Beyond military training, he also studied political science and international relations at prestigious institutions such as Harvard University and Oxford University, completing a master's degree in Political Science from Oxford in 1963.

2. Military Career

Chung Il-kwon's military career spanned service under the Japanese colonial administration, a brief period as a Soviet prisoner, and a distinguished but controversial command during the Korean War, culminating in his leadership of the Republic of Korea Army.

2.1. Service in Manchukuo and Japanese Armies

Upon graduating from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1940, Chung Il-kwon returned to Manchuria and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Manchukuo Imperial Army. He served as an instructor at the Jilin unit of the Manchukuo Army Military Police. He was involved in a special unit designed to blow up the Siberian Railway in case of conflict with the Soviet Union, undergoing three months of demolition training with Japanese special forces. He was then stationed in the Independent Military Police 3rd Regiment in Mohe, Heilongjiang Province.

In 1941, he was promoted to military police lieutenant and worked in the senior adjutant's office of the Manchukuo Army General Headquarters in Xinjing (Changchun). In 1942, he visited his alma mater, Gwangmyeong Middle School, and actively encouraged his juniors to enlist in the Manchukuo military, advocating that a military career offered the most promising future. After being promoted to military police captain, he served as the commander of the Gando Military Police Detachment in Yanji. At the time of Japan's surrender in August 1945, he held the rank of military police captain in the Manchukuo Imperial Army.

Historian Ryu Yeon-san asserted that Chung served as a Japanese Army Lieutenant Colonel and battalion commander of the Gando Military Police, making him the highest-ranking Korean in the Manchukuo military before liberation. He also claimed that Chung received multiple decorations from the Japanese Empire. These allegations have led to his inclusion in lists of pro-Japanese collaborators by South Korean research institutions, sparking ongoing historical debate regarding his actions during the colonial period.

2.2. Command during the Korean War

Following Japan's surrender, Chung Il-kwon quickly adapted to the changing political landscape. On August 15, 1945, he established the "Manchurian Korean Residents' Security Command" (later renamed "Northeast Area Restoration Army Command") in Xinjing, gathering approximately 400 Korean soldiers who had served in the Manchukuo and Kwantung Armies. This initiative was aimed at protecting Korean residents amid the chaotic post-war environment. However, in October 1945, he was apprehended by the Soviet intelligence agency KGB, which demanded he return weapons and join the establishment of a new military in North Korea after six months of re-education in Moscow. He attempted to escape Siberia-bound trains in December 1945 and successfully fled to Pyongyang, where he briefly stayed with his former military academy junior Paik Sun-yup, before making his way to Seoul.

In January 1946, he was commissioned as a captain (military number 5) in the newly formed South Korean National Defense Guard, serving as a company commander and later as a regiment commander. He was promoted to major in December 1946 and lieutenant colonel in 1947, serving as the Chief of Staff of the South Korean National Defense Guard and later as the head of the Korean Military Academy. In February 1949, he was promoted to brigadier general and appointed commander of the Jirisan District Combat Command on March 1, 1949. In this role, he participated in the suppression of South Korean Labor Party partisans in the Jirisan and other mountainous regions.

At the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, Chung was undergoing military training in Hawaii. He swiftly returned to Korea on June 30, was immediately promoted to major general, and replaced General Chae Byong-duk as the 5th Chief of Staff of the Republic of Korea Army. In July, he was also appointed the first Commander-in-Chief of the Republic of Korea Armed Forces, overseeing the Army, Navy, and Air Force. His initial responsibilities included regrouping the routed South Korean forces and coordinating with the United Nations Command. He played a crucial role as a tactical commander during the war, notably organizing South Korean soldiers for the Inchon Landing Operation in 1950, which significantly incapacitated the North Korean Army and established him as a war hero.

However, his tenure as Chief of Staff was marred by controversies such as the National Defense Corps Incident and the Geochang massacre, for which he was held accountable, leading to his resignation from both his Chief of Staff and Commander-in-Chief positions in June 1951. After further training in the United States, he returned in July 1952 but was demoted by President Syngman Rhee to a divisional command. Three months later, he was promoted to deputy commander of the U.S. IX Corps, commanding front-line UN forces. Three months after this, he was again promoted to command the ROK II Corps, which he held until the end of the war.

2.3. Post-War ROK Army Career

After the Korean War armistice, Chung Il-kwon continued his ascent within the Republic of Korea Army. In February 1954, he was promoted to general, becoming only the second general in the ROK Army, alongside Lee Hyung-geun. He was reappointed as the 8th Chief of Staff of the Republic of Korea Army in February 1954, succeeding Paik Sun-yup. In June 1956, he was appointed the 2nd Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He retired from active military service as a general in May 1957.

2.4. Military Influence and Factionalism

During the Syngman Rhee administration, Chung Il-kwon was a key figure in the military's internal power dynamics, often described as part of the "Three Great Generals" faction, alongside Paik Sun-yup and Lee Hyung-geun. He was also considered a leader of the "Manchukuo military faction," comprising officers who had served in the Manchukuo Imperial Army.

A notable conflict during his post-war military career was with Kim Chang-ryong, the head of the Army Counterintelligence Corps. In May 1954, as Chief of Staff, Chung appointed Gong Guk-jin as the new Military Police Commander, tasking him with eradicating corruption within the military. This led to frequent clashes between Gong and Kim Chang-ryong, who often overstepped his authority. Kim accused Gong of involvement in an ammunition shell smuggling scandal, attempting to remove him from office. Despite Chung's efforts to protect Gong, he was forced to dismiss him under pressure from Kim, who claimed to have direct orders from President Rhee.

Kim Chang-ryong further undermined Chung's authority by directly arresting Gong Guk-jin's aide, openly defying Chung's orders as Chief of Staff. Enraged by Kim's overreach, Chung Il-kwon and General Kang Moon-bong (a corps commander) personally appealed to President Rhee in October 1955, requesting Kim's transfer or study abroad. However, Rhee refused, reaffirming his trust in Kim. Kim retaliated by intensifying investigations into alleged corruption by Chung and Kang, which escalated into an extreme response: an alleged plot by Chung and Kang to assassinate Kim Chang-ryong. It was later revealed that President Rhee had secretly encouraged both Kim and Chung to investigate each other's alleged wrongdoings, a tactic that fueled internal military strife.

3. Diplomatic Career

After retiring from military service in May 1957, Chung Il-kwon embarked on a distinguished diplomatic career, serving as South Korea's ambassador to several key nations.

3.1. Ambassadorial Appointments

His first diplomatic posting was as the first Ambassador to Turkey in January 1957. In April 1959, he was appointed the first Ambassador to France, a position he held until 1960.

In May 1960, amidst the political transition following the April Revolution, Chung was designated Ambassador to the United States by the interim government, ahead of a planned visit by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He arrived in Washington, D.C. on June 5, presented his credentials to President Eisenhower on June 8, 1960, and served until September 1960. During his tenure as Ambassador to the U.S., he also concurrently served as ambassador to several South American countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, and Ecuador. He briefly returned to the U.S. as Ambassador from June 1961 to April 1963. While serving in Washington, he also acted as the Korean representative to the United Nations General Assembly.

During his diplomatic service in the United States, particularly after the May 16 coup in 1961, Chung Il-kwon played a crucial role in garnering support for the new military government under Park Chung Hee from the U.S. government and political circles. He toured various U.S. cities, advocating for the legitimacy of the military regime.

4. Political Career

Chung Il-kwon's transition from military and diplomatic service to a prominent political career was marked by his close alliance with President Park Chung Hee and his central role in key national policies, including the controversial normalization of relations with Japan.

4.1. Entry into Politics and Alignment

Following his diplomatic assignments, Chung Il-kwon returned to South Korean politics, aligning himself closely with President Park Chung Hee and the Democratic Republican Party. In December 1963, at Park Chung Hee's request, he was appointed Foreign Minister as the Third Republic of Korea was launched. During this period, he attempted to mediate conflicts between the ruling party's new cadres and Prime Minister Choi Du-sun, though without success.

4.2. Foreign Minister

Chung Il-kwon served two non-consecutive terms as Foreign Minister: first from December 1963 to July 1964, and again from December 1966 to June 1967, concurrently holding the Prime Minister position during his second term. In these roles, he was instrumental in the normalization of relations with Japan. He actively led negotiations and and played a key role in signing the Korea-Japan Normalization Treaty in June 1965, a move that was highly controversial and met with strong public opposition in South Korea due to lingering anti-Japanese sentiment from the colonial period and concerns over the terms of the agreement.

4.3. Prime Minister

On May 10, 1964, following the resignation of Prime Minister Choi Du-sun amidst widespread public protests against the Korea-Japan talks, Chung Il-kwon was appointed the 9th Prime Minister. He served for six years and seven months until December 20, 1970, making him the longest-serving prime minister in South Korean history. Upon his appointment, he pledged to swiftly resolve the Korea-Japan talks, increase food production, stabilize prices, and ensure transparent and efficient administration.

His tenure as Prime Minister was characterized by the Park Chung Hee government's focus on rapid economic development, often referred to as the "bulldozer cabinet" or "assault cabinet." However, it was also marked by significant political and social controversies. In 1966, his administration faced public outrage over the Saccharin Smuggling Incident involving the Samsung Group. This scandal led to the infamous "National Assembly Excrement Throwing Incident" in October 1966, where opposition lawmaker Kim Du-han threw excrement at the cabinet members, including Chung Il-kwon, during a parliamentary session, as a protest against government corruption and the handling of the incident.

4.4. National Assembly and Leadership

After his term as Prime Minister, Chung Il-kwon continued his political career as a member of the National Assembly. He was elected for three consecutive terms, serving from July 1971 to 1980, as a national proportional representative and later as a district representative for Sokcho, Inje, Goseong, and Yangyang in Gangwon Province, under the Democratic Republican Party.

From 1973 to 1979, he held the influential position of Speaker of the National Assembly during the Yushin period. Under the authoritarian Yushin system, the legislative branch was largely subservient to the executive, leading to public criticism that the National Assembly acted as a "maid" or "rubber stamp" for the administration. Despite holding a high parliamentary office, his role during this period is viewed critically as contributing to the erosion of parliamentary democracy and legislative independence. He also served as chairman of the Korean branches of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and the Asian Parliamentary Union (APU) in 1973. In 1979, he was appointed permanent advisor to the Democratic Republican Party's president and chairman of the Korea-Japan Parliamentarians' Union. He retired from politics in 1980.

5. Personal Life

Chung Il-kwon's personal life included multiple marriages and a complex family dynamic, as well as various names reflecting his diverse background.

5.1. Family and Marriages

Chung Il-kwon was married twice. His first wife was Yun Gye-won, with whom he had three daughters: Jeong Yeong-hye, Jeong Seong-hye, and Jeong Ji-hye. After Yun Gye-won's passing, he married Park Hye-soo. With his second wife, he had a son, Jeong Gi-hun (also known as Jeong Se-hun), and a daughter, Jeong Hui-jin. The birth of his children with his second wife, particularly his son, later became a point of contention and public discussion due to prior claims of sterility and his alleged involvement in the Jeong In-suk affair.

5.2. Names and Titles

Chung Il-kwon was known by several names throughout his life, reflecting his different cultural and historical affiliations:

- Birth Name**: His childhood name was 정일진Jeong Il-jinKorean (丁一鎭Korean).

- Art Name (Ho)**: He used the art name Chungsa (청사CheongsaKorean, 淸史Korean).

- Japanese Name**: During the Japanese colonial period, he adopted the Japanese name 中島一權Nakajima IkkenJapanese. He was also known by its Japanese pronunciation, Tei Ikken.

- Russian Notation**: In the Russian Far East during the 1930s, he was sometimes referred to as Ikken Tei (ИккЭн ТЭиIkken TeiRussian).

6. Controversies and Criticisms

Chung Il-kwon's career, while marked by high office and national service, is also associated with significant controversies that have drawn public and historical criticism, particularly concerning his actions during the Japanese colonial period and his alleged involvement in a high-profile scandal.

6.1. Collaborationist Accusations

One of the most persistent criticisms against Chung Il-kwon stems from his service in the Manchukuo Imperial Army and his alleged affiliation with the Japanese military during the colonial period. Historian Ryu Yeon-san claimed that Chung served as a Japanese Army Lieutenant Colonel and battalion commander of the Gando Military Police, and was the highest-ranking Korean in the Manchukuo military before liberation. He also claimed that Chung received multiple decorations from the Japanese Empire.

Due to this background, Chung Il-kwon was listed as a "pro-Japanese collaborator" by the Research Institute for Pro-Japanese Activities in 2008 for inclusion in its Dictionary of Pro-Japanese Collaborators. In 2009, he was formally designated as a "pro-Japanese anti-national collaborator" by the Presidential Committee for the Investigation of Pro-Japanese Collaborators. These designations highlight the ongoing debate in South Korea regarding the historical accountability of individuals who cooperated with the Japanese colonial regime, especially those who later held prominent positions in the independent Korean government.

6.2. The Jeong In-suk Affair

The Jeong In-suk murder case (1970) is one of the most sensational political scandals in South Korean history, with Chung Il-kwon allegedly at its center. On March 17, 1970, Jeong In-suk (정인숙Korean), a high-end hostess frequented by government officials, was found dead in Seoul's Mapo District, in what was initially staged as a traffic accident. The investigation quickly escalated into a major political scandal when a pocket notebook and ledger found in her home, inadvertently leaked to the press by police and prosecutors, revealed a list of dozens of high-ranking officials, including President Park Chung Hee, Prime Minister Chung Il-kwon, KCIA Director Kim Hyong-uk, Presidential Security Chief Park Jong-kyu, ministers, vice-ministers, generals, and heads of major conglomerates.

Rumors had long circulated that Jeong In-suk had a child with a powerful figure, with Chung Il-kwon, Park Chung Hee, or Lee Hu-rak (then Chief Presidential Secretary) frequently named as the father. Jeong In-suk's family, particularly her brother Jeong Jong-wook, later claimed that Chung Il-kwon was the father of her son, Jeong Seong-il, born in June 1968. Jeong Jong-wook stated that Chung frequently visited Jeong In-suk's home, expressed joy over the child, and even named him. It was alleged that Chung, fearing the scandal, advised Jeong In-suk to have an abortion but later encouraged her to give birth, subsequently arranging illegal passports for her to live abroad with financial support.

The scandal was widely satirized in popular culture, with lyrics mocking the situation, such as "If you ask who the father is, I'd say Mr. Jeong from the Blue House." The media's attempts to cover the story were often met with censorship. While President Park Chung Hee initially downplayed the affair, pressure from the opposition New Democratic Party intensified. Chung Il-kwon reportedly knelt before Park Chung Hee, who, fearing a greater scandal if he were immediately dismissed, advised him to resign voluntarily after Jeong Jong-wook's arrest. Chung resigned as Prime Minister on December 20, 1970, shortly after the scandal's peak.

In 1991, Jeong Seong-il filed a paternity suit against Chung Il-kwon, claiming he was his biological father. Jeong Seong-il stated that his maternal grandmother and uncle had told him since childhood that Chung had a relationship with his mother in 1967, leading to his birth the following year. Jeong Jong-wook, released from prison in 1989, publicly maintained that Chung Il-kwon was indeed the father and that he himself was innocent of his sister's murder. Sunwoo Ryeon, a former secretary to President Park Chung Hee, also claimed that Chung confessed to him in 1971 that Jeong Seong-il was his son. However, Chung Il-kwon himself denied paternity, claiming he had undergone a vasectomy and could not have fathered the child. This claim was later contradicted by the fact that he fathered two more children with his second wife after remarrying in 1977. Later, Jeong Seong-il appeared on a TV show in 1993, stating that Chung Il-kwon had told him he was "the son of the person I served," implying President Park Chung Hee.

Despite the conflicting claims, many close to the affair, including former politicians and family members, have stated that Chung Il-kwon was likely the father and provided significant financial support to Jeong Seong-il. The affair remains a symbol of the corruption and abuse of power by the ruling elite during South Korea's authoritarian period, highlighting the lack of social justice and accountability for high-ranking officials.

6.3. Criticisms of Political Tenure

Beyond the Jeong In-suk affair, Chung Il-kwon's political career, particularly his long tenure as Prime Minister and Speaker of the National Assembly under Park Chung Hee's rule, has drawn criticism for its role in supporting an authoritarian regime.

His administration's forceful push for the Korea-Japan Normalization Treaty in 1965, despite widespread public opposition and protests, is seen by critics as prioritizing political expediency and economic gains over national sentiment and historical justice. The government's suppression of these protests further underscored the authoritarian nature of the regime he served.

As Speaker of the National Assembly from 1973 to 1979, during the height of the Yushin system, he presided over a legislature that was largely stripped of its independence and power. Critics argue that the National Assembly under his leadership became a mere "maid" or "rubber stamp" for the executive branch, effectively undermining parliamentary democracy and legislative oversight. His actions during this period are viewed as contributing to the concentration of power in the presidency and the suppression of political dissent.

Furthermore, his involvement in the alleged power struggles within the military, such as the conflict with Kim Chang-ryong, also reflects a willingness to engage in factionalism and potentially unethical means to maintain influence, raising questions about his commitment to institutional integrity.

7. Death and Funeral

Chung Il-kwon's life concluded in the United States, followed by a state funeral in South Korea that drew comparisons with a contemporary democratic activist.

7.1. Illness and Passing

In March 1991, Chung Il-kwon traveled to Hawaii, United States, to receive treatment for lymphoma. Although he briefly returned to political activities in South Korea in 1992, supporting Kim Young-sam in the presidential election, his health deteriorated. In January 1994, he was re-hospitalized at Straub Hospital in Hawaii due to the worsening of his cancer. He passed away there on January 17, 1994, at the age of 77.

7.2. Funeral and Burial

His body was repatriated to South Korea by plane. A state funeral was held for him on the morning of January 22, 1994, in front of the National Assembly building in Seoul, presided over by National Assembly Speaker Lee Man-sup. Following the ceremony, his coffin was escorted by police to the Seoul National Cemetery in Dongjak-dong, Seoul, where he was interred in the generals' section.

His death on the same day as Mun Ik-hwan, a prominent democratic activist and his former middle school classmate, drew stark comparisons in the media. While Mun Ik-hwan, who had been imprisoned multiple times for his pro-democracy activities, received a massive public funeral attended by hundreds of thousands, Chung Il-kwon's funeral was a more formal state affair attended primarily by politicians at the national cemetery. This contrast highlighted the divergent paths their lives took, despite their shared beginnings, and left a lasting impression on the public.

8. Legacy and Evaluation

Chung Il-kwon's legacy in South Korean history is complex, marked by both significant contributions to national development and substantial criticisms regarding his political and military conduct.

8.1. Historical Assessment

Chung Il-kwon is often described as a "master of compromise" who was content with being second in command, never overtly seeking the highest power, and adapting to political realities rather than challenging them. He remained a loyal ally of President Park Chung Hee throughout his political career, often referring to Park with honorifics and praising him as a nationalist. He reportedly took pride in Park's consistent use of the honorific "senior" when addressing him.

He is recognized for his role in stabilizing the military after the Korean War and for his diplomatic efforts, particularly in the normalization of relations with Japan, which, despite its controversial nature, laid a foundation for South Korea's economic growth.

8.2. Contributions to National Development

Chung Il-kwon made notable contributions to South Korea's nation-building efforts, foreign policy, and political stability during a crucial period of its modern history. As a key military commander during the Korean War, he played a vital role in defending the nation, particularly during the Inchon Landing Operation.

In his diplomatic roles, he helped establish and strengthen South Korea's international standing, particularly through his ambassadorships to Turkey, France, and the United States. His efforts were crucial in securing international support for the nascent South Korean government.

As Prime Minister, he oversaw a period of rapid economic growth and development under the Park Chung Hee administration. While the policies were largely driven by President Park, Chung's role in implementing and managing the government's agenda contributed to the country's industrialization and modernization. He also initiated efforts for food production increase and price stabilization.

8.3. Critical Perspectives

Despite his achievements, Chung Il-kwon's career is subject to significant critical scrutiny, particularly concerning its impact on democracy, human rights, and social progress.

His service in the Manchukuo Imperial Army and alleged affiliations with the Japanese military during the colonial period have led to his official designation as a "pro-Japanese collaborator." This aspect of his past is viewed as a stain on his legacy, raising questions about his moral stance during a period of national oppression.

His alleged involvement in the Jeong In-suk murder case and the subsequent cover-up attempts highlight issues of corruption, abuse of power, and a lack of accountability among the ruling elite. The scandal underscored a system where powerful figures could seemingly operate above the law, undermining public trust and the principles of social justice.

Furthermore, his long tenure as a high-ranking official and parliamentary leader under the authoritarian Park Chung Hee regime and the Yushin system draws strong criticism. As Prime Minister and especially as Speaker of the National Assembly, he was seen as a key enabler of the authoritarian government, which suppressed political dissent, curtailed civil liberties, and concentrated power in the executive. His leadership of the National Assembly during this period is often cited as an example of the legislature's subservience to the executive, thereby hindering the development of genuine parliamentary democracy and human rights in South Korea.

9. Honors and Awards

Chung Il-kwon received numerous domestic and foreign decorations, as well as honorary academic degrees, recognizing his military and civilian service.

9.1. Domestic and Foreign Decorations

He was awarded several prestigious military and civilian honors from South Korea and other nations:

- South Korea**:

- Presidential Individual Commendation (June 1948)

- Chungmu Order of Military Merit (December 1950)

- Eulji Order of Military Merit

- Taeguk Order of Military Merit (October 1951)

- Taeguk Order of Military Merit (Gold Star)

- Blue Stripes Order of Civil Merit

- Order of Diplomatic Service Merit, Heungin Medal

- Order of Diplomatic Service Merit, Gwanghwa Medal (August 1970)

- Order of Military Merit (October 1969)

- United States**:

- Legion of Merit (Officer) (October 1950)

- Legion of Merit (Commander) (October 24, 1951)

- Silver Star (May 13, 1952)

- Distinguished Service Cross (November 3, 1953)

- Legion of Merit (Chief Commander) (April 29, 1957)

- Other Nations**:

- Ethiopia: Grand Star Order (April 1955), Order of the Holy Spirit (May 1968)

- Greece: Grand Cross Order (July 1955)

- France: Legion of Honour (July 1956)

- Philippines: Order of Merit (December 1956)

- Republic of China (Taiwan): First Class Order of Brilliant Star (October 1964), Special Grand Cordon Order of Brilliant Star (June 1974)

- Malaysia: Honorary Grand Commander of the Order of the Defender of the Realm (S.M.N.) (April 1965)

- Argentina: Grand Cross of the Order of San Martín (April 1966)

- Germany: First Class Grand Cross Order of Merit (March 1967)

- Thailand: Order of the White Elephant (April 1967), Knight Grand Cordon (Special Class) of the Order of the White Elephant (March 1978)

- El Salvador: Grand Silver Cross Order (October 1968)

- Tunisia: Grand Cordon Order (July 1969)

- Nigeria: Grand Cross Order (October 1969)

- Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (December 1969)

- Brazil: Grand Cross Order of Parliament (June 1974)

- Colombia: Special Gold Plate Grand Cross Order (June 1976)

- Mexico: First Class Order of Diplomatic Service Merit (October 1979)

9.2. Honorary Academic Degrees

Chung Il-kwon received several honorary doctorates from universities around the world:

- Honorary Doctor of Law, University of Malaya, Malaysia (October 1965)

- Honorary Doctor of Law, Chung-Ang University, South Korea (March 1966)

- Honorary Doctor of Law, Pusan National University, South Korea (June 1966)

- Honorary Doctor of Law, Saigon University, Vietnam (February 1967)

- Honorary Doctor of Law, Long Island University, United States (March 1967)

- Honorary Doctor of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand (September 1967)

- Honorary Doctor of Law, National Chengchi University, Republic of China (Taiwan) (February 1970)

- Honorary Doctor of Philosophy, Chinese Academy, Republic of China (Taiwan) (February 1971)

- Honorary Doctor of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand (February 1972)

- Honorary Doctor of Letters, University of Miami, Oxford College, United States (1988)

10. Works

Chung Il-kwon authored several publications, primarily his memoirs, which offer insights into his experiences and perspectives on the significant historical events he witnessed and participated in.

10.1. Writings and Memoirs

His notable published works include:

- War and Ceasefire (전쟁과 휴전Korean)

- Chung Il-kwon's Memoir (정일권 회고록Jeong Il-gwon HoegorokKorean (丁一權 回顧綠)) (published in 1991)