1. Overview

Antigonus I Monophthalmus, born in Macedonia around 382 BC, was a prominent Macedonian Greek general and one of the most influential Diadochi, the successors who contended for control of Alexander the Great's empire after his death. Known as "the One-Eyed" (Ἀντίγονος ΜονόφθαλμοςAntigonos MonophthalmosGreek, Ancient) due to a battle injury, Antigonus was a figure of immense ambition and military genius. He initially served under Philip II of Macedon before becoming a key commander in Alexander's campaigns against the Achaemenid Empire. Following Alexander's unexpected death in 323 BC, Antigonus emerged as a dominant force in the ensuing Wars of the Diadochi, controlling vast territories across Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia, Mesopotamia, and Greece. His ultimate goal was to reunite Alexander's sprawling empire under his sole rule, a pursuit that led to relentless conflicts with other Diadochi. In 306 BC, he declared himself basileus (king), founding the Antigonid dynasty, which would later rule Macedonia. However, his expansive ambitions ultimately led to a grand coalition of rivals, culminating in his decisive defeat and death at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. His fall solidified the fragmentation of Alexander's empire into several independent Hellenistic kingdoms, fundamentally shaping the political landscape of the ancient world for centuries.

2. Early Life and Background

Antigonus I Monophthalmus's early life and background laid the foundation for his distinguished military and political career, though specific details remain somewhat scarce.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Antigonus was born in Macedonia around 382 BC. His father was a nobleman named Philip, though his mother's name is not known. While some historical accounts have speculated about his origins, suggesting he might have come from a peasant background or even been linked to the Macedonian royal house, the most reliable evidence indicates that his family was socially prominent and belonged to the Macedonian nobility. Little is known about his formal education, but his later military prowess and strategic acumen suggest a thorough grounding in Macedonian military traditions and perhaps broader intellectual pursuits common among the aristocracy of his time. He was described as having a deep ambition from a young age, which motivated his entry into the Macedonian military.

2.2. Early Career

Antigonus began his military service under Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great. During Philip II's reign, a period of significant Macedonian expansion and military innovation, Antigonus established himself as an important figure in the Macedonian army. He was active alongside other prominent generals such as Eumenes, Parmenion, Polyperchon, and Antipater. His importance at Philip's court is further indicated by the friendships he forged with Antipater, who would become viceroy of Macedonia, and Eumenes, two of Philip's chief lieutenants.

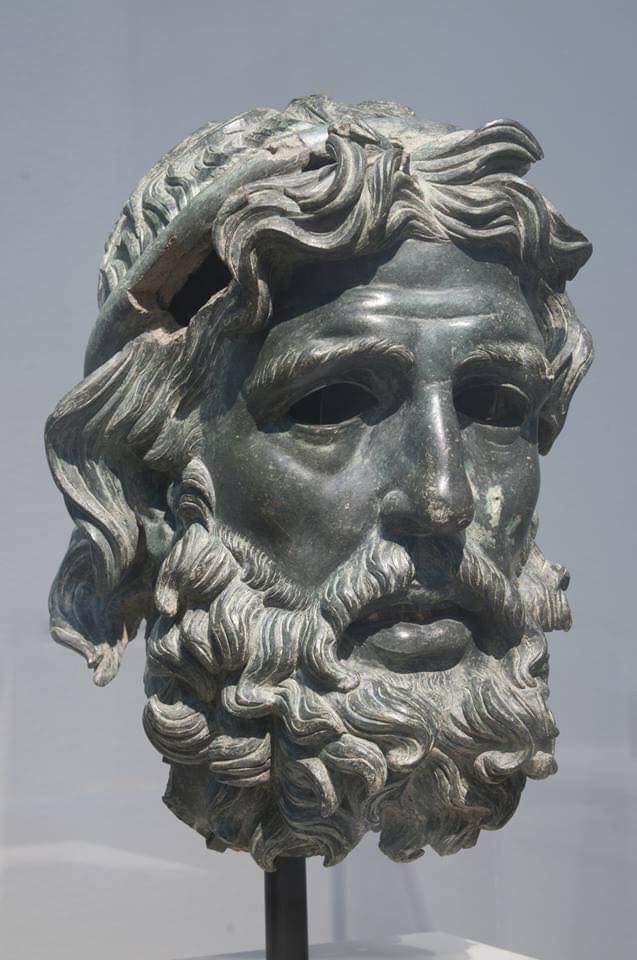

A notable incident in his early career occurred around 340 BC during the Siege of Perinthus. According to the ancient historian Plutarch, Antigonus lost an eye when a catapult bolt struck him. This injury earned him the enduring epithet "Monophthalmos" (ΜονόφθαλμοςMonophthalmosGreek, Ancient), meaning "the One-Eyed." It is speculated that he lost his left eye, a deduction made from portraits on coins that typically show him facing right. This physical characteristic, combined with his imposing stature, made his appearance even more formidable. The loss of his eye seemed to have left a psychological impact on him; Plutarch recounts an anecdote where a sophist named Theogrites was executed for satirizing Antigonus as a Cyclops, a one-eyed giant from Greek mythology.

3. Career under Alexander the Great

Antigonus's career under Alexander the Great marked his transition from a respected general of Philip II to a crucial figure in Alexander's grand campaign.

In 334 BC, at the outset of Alexander's invasion of the Persian Empire, the then 60-year-old Antigonus was appointed commander of the 7,000 allied Greek infantry. Although he did not participate in the Battle of the Granicus because Alexander, wary of his Greek infantry, left them behind, Antigonus was entrusted with a vital role. After Alexander marched eastward, he appointed Antigonus as satrap of Phrygia, a strategically important region in Asia Minor. Some sources also mention him briefly as Satrap of Lydia.

As Satrap of Phrygia, Antigonus's primary responsibility was to defend Alexander's lines of supply and communication, which stretched through the heart of Asia Minor, during the extended campaign against the Achaemenid Persian Empire. This was a challenging task, as Bithynia remained independent, and Paphlagonia, Cappadocia, Lycaonia, Isauria, and Pisidia were either under Persian satrapal control or did not recognize Macedonian authority. Furthermore, Memnon of Rhodes, loyal to Darius III, threatened Alexander's rear by leading a Persian fleet in the Aegean Sea.

Antigonus proved highly effective in this role. After Alexander's victory at the Battle of Issus, remnants of the Persian army, including a cavalry force of 20,000 under Nabazarnes, regrouped in Cappadocia and attempted to sever Alexander's supply lines. Antigonus successfully repelled these counter-attacks, defeating the Persian forces in three separate battles in Cappadocia and Paphlagonia in the spring of 332 BC. The death of Memnon of Rhodes further neutralized the Persian naval threat. Following these successes, Antigonus focused on conquering the remaining parts of Phrygia and ensuring the uninterrupted flow of supplies and communications for Alexander's ongoing conquests. His steadfast performance in this critical logistical and defensive role allowed Alexander to continue his deep penetration into the Persian Empire without fear of his rear being cut off.

4. The Wars of the Diadochi

The period following Alexander the Great's death plunged his vast empire into a series of protracted and brutal conflicts among his generals, known as the Diadochi. Antigonus I Monophthalmus played a central and often dominant role in these struggles, driven by his ambition to reunite the empire under his own rule.

4.1. After Alexander's Death and the First War of the Diadochi

Upon Alexander the Great's sudden death in Babylon in 323 BC, the issue of succession immediately arose. Alexander's wife, Roxana, was pregnant, and he had not named a clear heir. This uncertainty sparked a power vacuum among his leading generals. At the Partition of Babylon, an initial division of the empire, Antigonus's authority over Phrygia, Lycaonia, Pamphylia, Lycia, and western Pisidia was confirmed by Perdiccas, who was appointed regent for Alexander's infant son, Alexander IV of Macedon, and Alexander's half-brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus.

However, Antigonus soon incurred the enmity of Perdiccas. He refused to assist Eumenes in taking possession of his allotted provinces of Paphlagonia and Cappadocia, likely fearing Eumenes would become a rival in Asia Minor. Perdiccas viewed this as a direct challenge to his authority and personally led the royal army to conquer Cappadocia before turning towards Phrygia as a provocation against Antigonus. Recognizing the threat, Antigonus fled with his son, Demetrius, to Greece. There, he forged a powerful alliance with Antipater, the viceroy of Macedonia, and Craterus, one of Alexander's most respected generals, later joined by Ptolemy, the satrap of Egypt.

This coalition marked the beginning of the First War of the Diadochi. In 320 BC, Antigonus successfully secured Cyprus for the alliance. The war concluded later that year when Perdiccas, during an unsuccessful invasion of Ptolemy's satrapy in Egypt, was murdered by his own discontented officers, including Seleucus and Antigenes.

With Perdiccas's death, a new division of the empire was arranged at the Treaty of Triparadisus in 321 BC. Antipater was named the new regent, and Antigonus was appointed Strategos (Commander-in-Chief) of Asia, entrusted with the command of the war against the remaining members of the Perdiccan faction who had been condemned at Triparadisus. Antigonus, reinforced by Antipater's European troops, marched against Eumenes, Alcetas, Docimus, Attalus, and Polemon in Asia Minor. He first targeted Eumenes in Cappadocia, defeating him at the Battle of Orkynia despite being outnumbered, forcing Eumenes to retreat to the fortress of Nora. Leaving Eumenes under siege, Antigonus then swiftly moved against the combined forces of Alcetas, Docimus, Attalus, and Polemon near Cretopolis in Pisidia. He surprised and decisively defeated them at the Battle of Cretopolis. In two brilliant campaigns within a single season, Antigonus effectively annihilated the remnants of the Perdiccan faction, leaving only Eumenes contained in Nora.

4.2. The Second War of the Diadochi

The death of Antipater in 319 BC ignited the Second War of the Diadochi. Antipater had designated Polyperchon as his successor for the regency, bypassing his own son, Cassander. Antigonus and the other powerful dynasts refused to recognize Polyperchon's authority, viewing it as an obstacle to their own ambitions.

Antigonus initially entered negotiations with Eumenes, who was still besieged in Nora. However, Eumenes had already been swayed by Polyperchon, who offered him supreme authority over all other generals within the empire. Eumenes managed to escape Nora through cunning and began raising a small army, fleeing south into Cilicia. Antigonus could not immediately pursue Eumenes because he was occupied in northwestern Asia Minor, campaigning against Cleitus the White, who commanded a large fleet at the Hellespont. Cleitus initially defeated Antigonus's admiral Nicanor in a naval battle, but Antigonus and Nicanor launched a surprise double assault by land and sea on Cleitus's camp the next morning, completely overwhelming his forces at the Battle of Byzantium.

Meanwhile, Eumenes had consolidated control over Cilicia, Syria, and Phoenicia, forming an alliance with Antigenes and Teutamos, commanders of the elite Silver Shields and Hypaspists. He also began building a naval force for Polyperchon. However, when this fleet sailed west, it encountered Antigonus's fleet off the coast of Cilicia and defected to his side. With his affairs in Asia Minor settled, Antigonus marched east into Cilicia, intending to confront Eumenes in Syria. Eumenes, having advance knowledge of Antigonus's movements, marched out of Phoenicia, through Syria, and into Mesopotamia, seeking support from the upper satrapies.

Eumenes secured the support of Amphimachos, the satrap of Mesopotamia, and then moved his army into Northern Babylonia for winter quarters. During this winter, he attempted to negotiate with Seleucus, the satrap of Babylonia, and Peithon, the satrap of Media, for their assistance against Antigonus, but was unsuccessful. Antigonus, learning of Eumenes's departure, secured Cilicia and northern Syria before pursuing him into Mesopotamia. Eumenes, unable to gain the support of Seleucus and Peithon, left his winter quarters early and marched on Susa, a major royal treasury in Susiana. From Susa, Eumenes dispatched letters to all satraps north and east of Susiana, ordering them in the kings' names to join him with all their forces. With these reinforcements, Eumenes commanded a formidable army. He then marched southeast into Persia, gaining further reinforcements.

Antigonus, meanwhile, reached Susa and left Seleucus to besiege the city while he pursued Eumenes. At the Kopratas River, Eumenes surprised Antigonus during a river crossing, inflicting heavy casualties (4,000 men killed or captured). Faced with disaster, Antigonus abandoned the crossing and turned northward into Media, threatening the upper satrapies. Eumenes wished to march westward to cut Antigonus's supply lines, but his allied satraps refused to abandon their own territories, forcing Eumenes to remain in the east. In late summer 316 BC, Antigonus again moved southward, hoping to force a decisive battle. The two armies finally met in southern Media at the indecisive Battle of Paraitakene. Antigonus, having suffered more casualties, force-marched his army to safety that night.

During the winter of 316-315 BC, Antigonus attempted a surprise attack on Eumenes in Persia by marching his army across a desert. However, locals observed his movements and reported them to Eumenes. A few days later, the armies engaged in the Battle of Gabiene, which was as indecisive as Paraitakene. According to Plutarch and Diodorus, Eumenes had won the battle but lost control of his army's baggage camp due to the treachery or incompetence of his ally, Peucestas. This loss was particularly devastating for the Silver Shields, as the camp contained loot accumulated over 30 years of warfare, along with their families. Approached by Teutamus, one of their commanders, Antigonus offered to return the baggage train in exchange for Eumenes. The Silver Shields complied, arresting Eumenes and his officers and handing them over.

With Eumenes captured, the war concluded. Eumenes was held under guard while Antigonus convened a council to decide his fate. Antigonus, supported by his son Demetrius, was inclined to spare Eumenes, but the council overruled them, and Eumenes was executed. Some accounts suggest Antigonus, unwilling to personally harm his former friend, allowed Eumenes to be starved to death, or that Eumenes was secretly killed by Antigonus's subordinates during a march. Antigonus, however, arranged a lavish funeral for Eumenes and sent his ashes in a silver urn to his family. Following the Battle of Gabiene, Antigonus also had Peithon, the satrap of Media and his nominal ally, executed due to Peithon's ambitions for the eastern territories.

As a result of these victories, Antigonus now controlled the vast Asian territories of Alexander's empire, stretching from the eastern satrapies to Syria and Asia Minor in the west. He seized the treasuries at Susa and entered Babylon. However, Seleucus, the governor of Babylon, fled to Ptolemy and formed an alliance with him, Lysimachus, and Cassander, setting the stage for the next phase of the Diadochi Wars.

4.3. The Third War of the Diadochi

Antigonus's rapid expansion and consolidation of power in Asia led to the formation of a formidable coalition against him. In 314 BC, Ptolemy, Cassander, and Lysimachus sent envoys to Antigonus, demanding that he cede Cappadocia and Lycia to Cassander, Hellespontine Phrygia to Lysimachus, Phoenicia and Syria to Ptolemy, and Babylonia to Seleucus, and that he share the immense wealth he had accumulated. Antigonus's only response was to advise them to prepare for war, effectively initiating the Third War of the Diadochi.

Antigonus immediately began to counter his enemies. He dispatched Aristodemus with 1,000 talents to the Peloponnesus to raise an army and forge an alliance with his old enemy, Polyperchon, instructing them to wage war against Cassander in Greece. He also sent an army under his nephew, Polemaeus, through Cappadocia to the Hellespont to prevent Cassander and Lysimachus from invading Asia Minor. Antigonus himself invaded Phoenicia, which was under Ptolemy's control, and laid siege to Tyre. The siege lasted for a year. After securing Phoenicia, Antigonus marched his main army into Asia Minor, intending to eliminate Asander (the satrap of Lydia and Caria and an ally of Ptolemy and Cassander), leaving the defense of Syria and Phoenicia to his eldest son, Demetrius.

By 312 BC, Antigonus had successfully captured Lydia and all of Caria, driving off Asander. He then sent his nephews, Telesphorus and Polemaeus, against Cassander in Greece. While Antigonus was engaged in the west, Ptolemy exploited the situation and launched an invasion from the south. Ptolemy's forces met Demetrius's army at the Battle of Gaza, where Ptolemy achieved a stunning victory. Following this battle, Seleucus, who had been fighting alongside Ptolemy, made his way back to Babylonia. He quickly re-established control over his former satrapy and proceeded to secure the eastern provinces against Antigonus. Seleucus's conquests initiated the Babylonian War, during which he defeated both Demetrius and Antigonus, solidifying his control over the eastern territories. After the Babylonian War, which lasted from 311 BC to 309 BC, a peace treaty was concluded between Antigonus and Seleucus, allowing both to consolidate their power in their respective realms: Antigonus in the west and Seleucus in the east.

In the west, Antigonus had effectively worn down his enemies and forced them into a peace agreement. By this treaty, he reached the zenith of his power. Antigonus's empire and alliance system now encompassed Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia, and northern Mesopotamia.

4.4. The Fourth War of the Diadochi and the Battle of Ipsus

The peace agreement was short-lived, soon violated by Ptolemy and Cassander under the pretext that Antigonus had placed garrisons in some of the free Greek cities. This led to the renewal of hostilities and the commencement of the Fourth War of the Diadochi. Antigonus's son, Demetrius Poliorcetes, swiftly moved to wrest control of parts of Greece from Cassander.

In 306 BC, a significant personal blow struck Antigonus with the premature death of his youngest son, Philip, at the age of 26-28. This loss deprived Antigonus not only of a son but also of a valuable general for the impending campaigns.

Following Demetrius's decisive naval victory over Ptolemy at the Battle of Salamis in 306 BC, which also led to the conquest of Cyprus, Antigonus assumed the title of king (basileus). He also bestowed the same royal rank upon his son. This act was a clear declaration of Antigonus's independence from the nominal empire and his claim to supreme authority, a position that had been vacant since the death of Alexander IV in 309 BC. The other powerful dynasts-Cassander, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Seleucus-soon followed Antigonus's lead, each declaring themselves kings in their own right, thus formalizing the fragmentation of Alexander's empire into distinct Hellenistic kingdoms.

Antigonus then prepared a massive army and a formidable fleet, placing Demetrius in command, and launched an invasion of Ptolemy's dominions in Egypt. However, his invasion proved unsuccessful; he was unable to breach Ptolemy's defenses and was forced to retreat, though he inflicted heavy losses on Ptolemy's forces.

In 305 BC, Demetrius attempted to subdue Rhodes, which had refused to assist Antigonus against Egypt. The siege lasted for a year, during which Demetrius deployed immense siege engines, including the famous Helepolis. Despite his efforts, Demetrius encountered tenacious resistance and was ultimately compelled to conclude a peace treaty in 304 BC. The terms stipulated that the Rhodians would build ships for Antigonus and aid him against any enemy, with the crucial exception of Ptolemy, whom the Rhodians honored with the epithet Soter ("savior") for his aid during the lengthy siege.

The increasing power and territorial ambitions of Antigonus, now a declared king, prompted the most powerful dynasts of the former empire-Cassander (ruler of Macedonia), Seleucus (ruler of the eastern satrapies), Ptolemy (ruler of Egypt), and Lysimachus (ruler of Thrace)-to form a grand alliance against him. This alliance was often cemented through strategic marriages. Antigonus soon found himself at war with all four, largely because his vast territory shared borders with each of them.

In 304-303 BC, Demetrius had placed Cassander in a precarious position in Greece, having gained significant support from the Greek cities and repeatedly defeating Cassander's forces. Antigonus then demanded the unconditional submission of Macedonia from Cassander. In response, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and Ptolemy joined forces and launched a coordinated attack. Lysimachus, accompanied by Cassander's general Prepelaos, invaded Asia Minor from Thrace, crossing the Hellespont, and quickly secured most of the Ionian cities. Simultaneously, Seleucus marched his forces through Mesopotamia and Cappadocia. Antigonus was compelled to recall Demetrius from Greece, where his son had recently engaged in an indecisive encounter with Cassander in Thessaly. Antigonus and Demetrius then moved to confront Lysimachus and Prepelaos.

The decisive confrontation occurred at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, where the combined forces of Seleucus, Lysimachus, and Prepelaos faced the army of Antigonus and Demetrius. Antigonus, then in his eighty-first year, was struck by a javelin and died during the battle. Prior to Ipsus, he had never lost a major battle. His death marked the definitive end of any plans to reunite Alexander's vast empire. Antigonus's kingdom was subsequently divided among the victors, with most of his territories falling into the hands of Lysimachus and Seleucus. While the victorious kings followed Antigonus's precedent by assuming royal titles, they did not claim authority over Alexander's entire former empire or over each other. Instead, they established a troubled but ultimately enduring system of separate Hellenistic realms.

5. Rule and the Antigonid Dynasty

Antigonus I Monophthalmus's assumption of the royal title and his founding of the Antigonid dynasty were pivotal moments in the Hellenistic period, formalizing the fragmentation of Alexander's empire into distinct kingdoms.

In 306 BC, following his son Demetrius's victory at the Battle of Salamis in Cyprus, Antigonus declared himself basileus (king). This bold move was a direct challenge to the regency system that had nominally governed Alexander's empire and a clear assertion of his independent sovereignty. By taking the royal title, Antigonus effectively laid claim to the entirety of Alexander's former dominion. He also bestowed the same royal rank upon his son, Demetrius, solidifying their joint claim to a new dynastic rule.

This declaration by Antigonus prompted a cascade of similar actions from the other leading Diadochi. Within a short period, Cassander, Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Seleucus also proclaimed themselves kings, abandoning any pretense of a unified empire. This collective adoption of royal titles marked the official end of Alexander's empire and the beginning of the Hellenistic monarchies, each ruling over its own distinct territory.

Antigonus's kingdom, often referred to as the Antigonid Empire, was vast, encompassing Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia, and northern Mesopotamia at its peak. His administration was characterized by a centralized military and financial system designed to support his ambitious campaigns. He controlled key treasuries, such as the one at Susa, and commanded a formidable army and navy.

Despite Antigonus's death at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC and the subsequent division of his vast territories among his rivals, his dynastic legacy endured. His surviving son, Demetrius I Poliorcetes, managed to retain a significant portion of his father's naval power and influence in Greece. In 294 BC, Demetrius succeeded in seizing control of Macedonia after assassinating Alexander V of Macedon, Cassander's son. The Antigonid dynasty, founded by Antigonus, would continue to rule Macedonia, albeit with periods of interruption, until its final conquest by the Roman Republic after the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC. Thus, while Antigonus failed in his grand ambition to reunite Alexander's empire, he successfully established a powerful and enduring Hellenistic dynasty that played a central role in the political landscape for over a century.

6. Family and Personal Life

Antigonus I Monophthalmus's family connections and personal characteristics provide insight into his social standing and the challenges he faced throughout his life.

Antigonus was the son of a nobleman named Philip. While his mother's name is not recorded in historical sources, his family was part of the Macedonian nobility, suggesting a background of influence and privilege. He had an older brother named Demetrius and a younger brother named Polemaeus, who was the father of the general Polemaeus. Another nephew, Telesphorus, may have been the son of a third, unnamed brother. He also had a younger half-brother, Marsyas, from his mother's second marriage to Periander of Pella.

Antigonus was married to Stratonice, who was the widow of his older brother. This marriage was likely a strategic alliance, common among the Macedonian aristocracy, to consolidate family ties and influence. Together, Antigonus and Stratonice had two sons: Demetrius I Poliorcetes and Philip. Demetrius would become his father's most trusted general and successor, while Philip died prematurely in 306 BC, a significant loss for Antigonus.

Antigonus was known for his imposing physical presence. He was described as an exceptionally large man. His son, Demetrius, was noted for his "heroic stature," implying a large physique, but Antigonus was reportedly even taller. His most distinguishing physical feature, however, was his missing eye, which earned him the epithet "Monophthalmos." He lost this eye in battle, possibly during the Siege of Perinthus in 340 BC, when he was struck by a catapult bolt. This injury, while a mark of his military career, also became a defining characteristic, making him appear even more formidable.

7. Death and Legacy

Antigonus I Monophthalmus's death at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC marked a definitive turning point in the Wars of the Diadochi and had a profound impact on the subsequent development of the Hellenistic world.

Antigonus met his end on the battlefield of Ipsus, in Phrygia, at the age of 80 or 81. He was struck by a javelin during the decisive engagement against the combined forces of Seleucus, Lysimachus, and Cassander's general Prepelaos. His death was particularly significant because, prior to Ipsus, Antigonus had never lost a major battle, a testament to his military genius and strategic prowess.

With Antigonus's fall, his grand ambition to reunite Alexander the Great's empire under a single rule came to an abrupt end. His vast kingdom, which at its peak stretched across Asia Minor, Syria, Phoenicia, and northern Mesopotamia, was immediately divided among the victors. Lysimachus and Seleucus acquired the largest portions of his former territories. This division solidified the fragmentation of Alexander's empire into several independent Hellenistic kingdoms, each ruled by one of the Diadochi or their descendants. These new kings, having followed Antigonus's lead in declaring themselves monarchs, no longer claimed authority over the entire former empire but rather accepted their realms as distinct entities. This established a new, albeit often contentious, political order that defined the Hellenistic period.

Despite his ultimate defeat and the partition of his empire, Antigonus's legacy endured through his son, Demetrius I Poliorcetes. Demetrius, though defeated at Ipsus, managed to escape with a significant portion of his forces and fleet. He eventually succeeded in seizing control of Macedonia in 294 BC. The Antigonid dynasty, founded by Antigonus, continued to rule Macedonia intermittently until its final conquest by the Roman Republic following the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC. Thus, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, despite failing in his ultimate goal of imperial reunification, successfully established one of the most significant and long-lasting Hellenistic dynasties, profoundly influencing the political landscape and power dynamics of the ancient Mediterranean world for over a century.

8. Assessment and Historical Spotlight

Antigonus I Monophthalmus stands as one of the most compelling and consequential figures of the early Hellenistic period. His historical assessment highlights his exceptional military genius, relentless ambition, and complex political strategies, all of which had profound socio-political consequences.

Militarily, Antigonus was unparalleled among the Diadochi for much of his career. His tactical brilliance was evident in his ability to repeatedly defeat larger forces, such as his campaigns against the remnants of the Perdiccan faction at Orkynia and Cretopolis, and his sustained pressure on Eumenes. His strategic acumen allowed him to maintain Alexander's supply lines in Asia Minor, a critical but often overlooked task, and later to expand his own domain across vast territories. His record of never losing a battle before Ipsus underscores his formidable reputation as a commander.

However, Antigonus's defining characteristic was his ambition. He harbored the grand vision of reuniting Alexander's empire under his sole rule, a goal that set him apart from most other Diadochi who were content with establishing regional kingdoms. This ambition, while a driving force behind his successes, also became his undoing. His relentless expansion and refusal to compromise with his rivals led to the formation of powerful coalitions against him. The socio-political consequence of his ambition was not a unified empire, but rather its permanent fragmentation into independent Hellenistic states, each vying for power. His actions, therefore, inadvertently solidified the very division he sought to overcome.

Politically, Antigonus was a shrewd operator. He understood the importance of alliances, as demonstrated by his early coalition with Antipater and Ptolemy against Perdiccas. He was also capable of ruthless pragmatism, as seen in his eventual decision to execute Eumenes, despite initial inclinations to spare him, to eliminate a persistent threat and consolidate his power. His declaration of kingship in 306 BC was a bold political statement that not only asserted his sovereignty but also forced the hands of the other Diadochi, leading them to declare their own royal titles and formally acknowledge the new era of independent Hellenistic monarchies.

From a critical perspective, Antigonus's pursuit of a unified empire, while perhaps driven by a sense of loyalty to Alexander's legacy, ultimately contributed to decades of devastating warfare that cost countless lives and resources. His actions, though militarily brilliant, were primarily focused on personal power and territorial expansion, rather than on fostering stability or democratic institutions. The constant conflicts he initiated or engaged in created a volatile political landscape, delaying the establishment of stable governance in the regions he controlled. His reign, therefore, represents a period of intense upheaval and transition, where the ideals of a unified empire clashed with the realities of individual ambition, ultimately paving the way for the diverse and often warring Hellenistic kingdoms that followed.

9. Antigonus in Popular Culture

Antigonus I Monophthalmus, a pivotal figure in the tumultuous aftermath of Alexander the Great's empire, has been portrayed and interpreted in various modern cultural works, reflecting different facets of his historical persona.

In literature, Mary Renault's historical novel Funeral Games translates Antigonus's sobriquet directly into English as "One Eye," emphasizing his distinctive physical trait. L. Sprague de Camp features Antigonus, under the Greek form of his name (Antigonos), in his historical novels An Elephant for Aristotle and The Bronze God of Rhodes, which are set approximately two decades apart. These novels likely explore his strategic mind and his role in the broader Hellenistic world. Christian Cameron's historical novel A Force of Kings casts Antigonus as the main antagonist, suggesting a focus on his formidable and often ruthless pursuit of power. He also appears in the earlier chapters of Alfred Duggan's historical novel Elephants and Castles (published in the U.S. as Besieger of Cities), which centers on the life of his son, Demetrius, providing a glimpse into their complex father-son dynamic. Additionally, Antigonus is a supporting antagonist in Eric Flint's alternate history novel The Alexander Inheritance and its sequel, The Macedonian Hazard, indicating his enduring presence as a significant historical adversary.

In film, Antigonus is depicted in the 2004 movie Alexander, directed by Oliver Stone, where he is portrayed by actor Ian Beattie. These portrayals in popular culture contribute to the public's understanding and imagination of Antigonus, often highlighting his military prowess, his distinctive physical appearance, and his role as a key player in the dramatic power struggles of the Diadochi.