1. Early Life and Education

Ume Kenjirō's early life and educational journey demonstrated exceptional intellect and laid the groundwork for his distinguished legal career.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

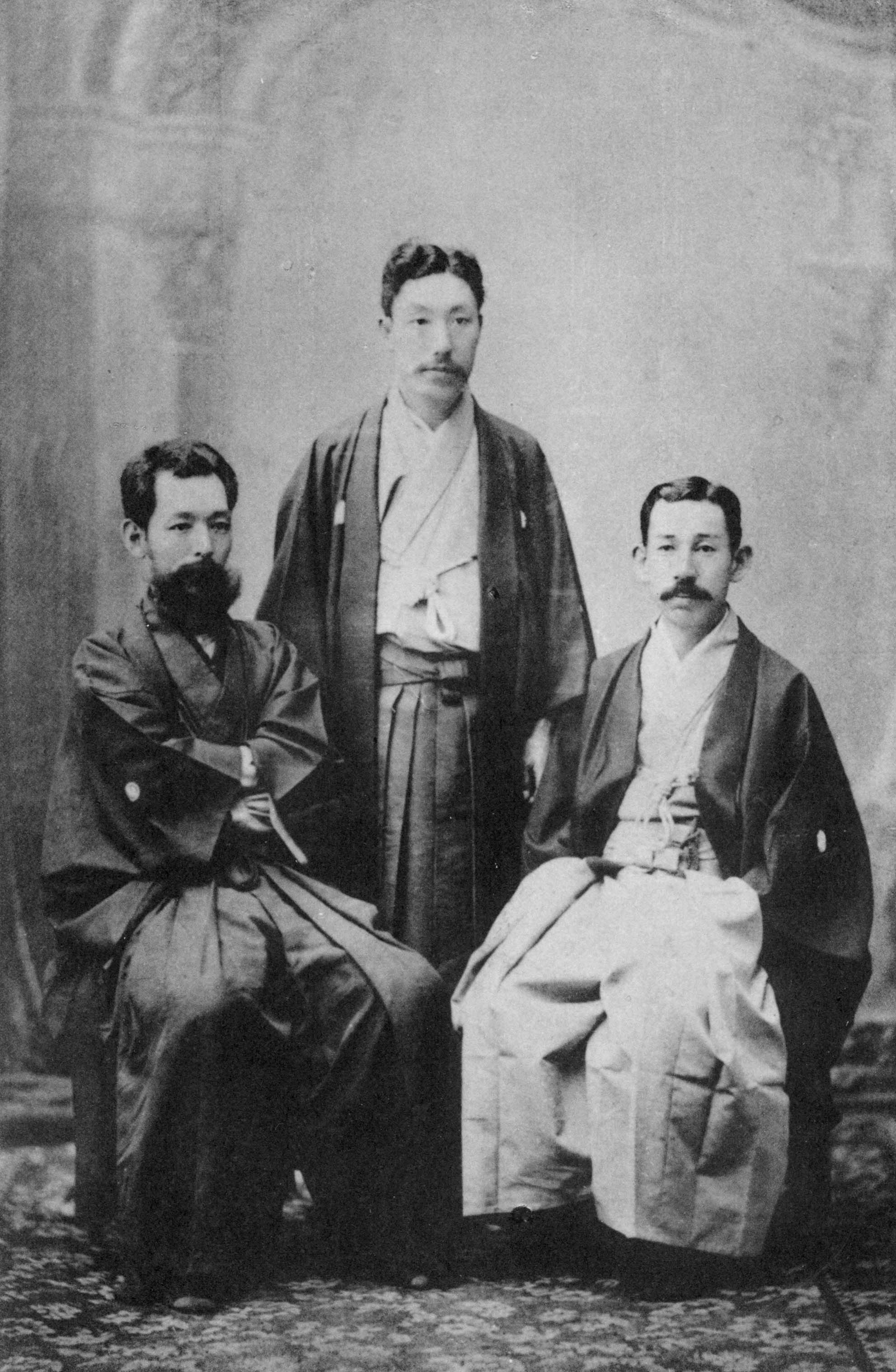

Ume Kenjirō was born on July 24, 1860, as the second son of Ume Kaoru, a domain doctor in the Matsue Domain (present-day Matsue City, Shimane Prefecture, Izumo Province). His family had a long lineage of physicians; his great-great-grandfather, Ume Dochiku, was the first to become a Matsue domain physician. His older brother, Ume Kinnojō (1858-1886), also achieved prominence as an ophthalmologist, becoming the first Japanese person to deliver lectures and conduct medical examinations in ophthalmology, and served as the first professor of ophthalmology at Tokyo Imperial University's Faculty of Medicine. Ume Kinnojō is believed to be the "Ume-bō" mentioned in Mori Ōgai's "German Diary."

1.2. Childhood and Early Talent

Ume Kenjirō exhibited remarkable academic brilliance from a young age. At just six years old, he could recite classical Chinese texts such as Daigaku and Chūyō from memory, earning him praise as the "reincarnation of Nichirō." Despite being frail, he possessed a strong will and excelled in debates. At the age of twelve, he delivered a lecture on the Nihon Gaishi (Unofficial History of Japan) before the domain lord, for which he received a commendation, further demonstrating his precocious talent.

1.3. Legal Education in Japan

His formal education continued to showcase his exceptional abilities. Ume Kenjirō graduated at the top of his class from the French Language Department of the Tokyo Foreign Language School (the precursor to the modern Tokyo University of Foreign Studies). Following this, he entered the Judicial Ministry Law School to study French law. From the outset, he consistently held the top position in his class. Although he could not take the final examination due to illness, he still graduated as valedictorian based solely on his regular academic performance. His instructor at the Judicial Ministry Law School was Georges Appert. Notably, Ume Kenjirō was initially rejected from the entrance examination for the second term of the Judicial Ministry Law School. However, he gained admission after Hara Takashi (who would later become Prime Minister of Japan), who had initially placed second, withdrew from the school due to his involvement in the "Wai Seibatsu" student protest over school management.

1.4. Overseas Studies and Degree

In 1886, Ume Kenjirō was granted a scholarship by the Ministry of Education to study abroad in France. He pursued doctoral studies (Doctorat) at the University of Lyon, where he advanced rapidly through the program by skipping grades. He earned his Doctor of Law degree, again graduating at the top of his class. His doctoral dissertation, titled De la transactionFrench (Theory of Settlement), received significant acclaim and was awarded the Vermeil Prize by the City of Lyon, leading to its publication at public expense. The dissertation was highly regarded internationally; it was reviewed in a German legal journal in 1891 and even cited in French legal encyclopedias, with its interpretations remaining relevant in French civil law to this day. After completing his studies in Lyon, he spent an additional year studying at Humboldt University of Berlin in Germany. He returned to Japan in August 1890, after which he was heavily relied upon by Itō Hirobumi as a key intellectual advisor.

2. Legal Career and Public Service

Ume Kenjirō's professional life was marked by extensive contributions to legal scholarship, public administration, and significant legal reforms.

2.1. Academic and Judicial Career

Upon his return to Japan in 1890, Ume Kenjirō became a professor at the Imperial University Faculty of Law (now the University of Tokyo Faculty of Law) and concurrently served as a counsellor for the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. While he initially intended to dedicate himself exclusively to his professorship at the Imperial University, he was persuaded to also teach at private institutions. This came about through the persistent requests of Tomii Masaaki (a colleague and brother-in-law of Satta Masakuni, a founder of Hosei University) and Motono Ichirō (then a lecturer at Wafutsu Law School, whom Ume had known during his studies in Lyon). They traveled to Yokohama Port to personally appeal to him upon his return, leading him to accept the concurrent position of Academic Supervisor at Wafutsu Law School. He also taught at Tokyo Senmon Gakkō (the precursor to Waseda University).

2.2. Role in Civil Code Drafting

Ume Kenjirō became deeply involved in the Civil Code controversy that was unfolding in Japan upon his return. He initially advocated for the immediate implementation of the Civil Code drafted by Gustave Emile Boissonade, a French foreign advisor to the Japanese government. His stance, known as the "dankō-ron" (immediate implementation theory), was driven by a desire to unify judicial practice and facilitate the revision of unequal treaties. However, he was also critically aware of the code's imperfections, stating that "the defects of the Civil Code are too numerous to count" and offering detailed academic critiques. Despite his criticisms of the initial draft, his fair and sincere academic approach was a key factor in his selection as a member of the new Civil Code drafting committee in 1893, following the postponement of the code's adoption in 1892. He had appealed to Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi to establish this new committee.

Ume Kenjirō is regarded as one of the three "fathers of Japan's civil law," alongside Hozumi Nobushige and Tomii Masaaki, who collectively saw the code into effect in 1898. He prioritized the swift completion of the code, even if it meant leaving minor imperfections for future revisions, a pragmatic approach that contrasted with Tomii's pursuit of perfection. According to Hozumi's Hōshōyawa, Ume possessed a sharp intellect and was remarkably quick in drafting legal texts. During drafting committee discussions, he was open to criticism from Hozumi and Tomii, willing to revise his own views. However, once a draft was finalized by the committee, he became a robust and eloquent defender of the original proposal within the larger Law Codification Committee, striving to maintain the agreed-upon text. This "outside-man" approach contrasted with Tomii's "inside-man" style, where Tomii would thoroughly deliberate on legal texts but be more flexible in the Codification Committee. Hozumi playfully noted that "Dr. Ume was a true Benkei," referring to the legendary warrior monk known for his strength and loyalty.

His rapid logical operations and speed were considered crucial for the completion of the Civil Code. While Hozumi and Tomii exerted greater influence over the structural organization of the code (Ume initially favored placing the family law section as the second book, contrary to the final version), Ume's frequent participation and extensive remarks in the Law Codification Committee indicate his significant role in accelerating the code's completion. Despite his intellectual brilliance, some critics noted that his arguments could sometimes be forced, and he struggled with providing unified, systematic explanations compared to Tomii. For instance, the section on mortgage law, which Ume primarily drafted, was criticized for its complexity and the impracticality of specific concepts like dejō (a system of redemption). Nonetheless, Itō Hirobumi, then President of the Law Codification Committee, held Ume in high regard, addressing him as "Ume-sensei" (Professor Ume) while referring to Hozumi and Tomii with less formal titles. Ume Kenjirō was hailed as an "unprecedented legislator" and a "born jurist," and remains the only Japanese legal scholar to be singularly featured on a Japanese postage stamp as part of the cultural figures series, underscoring his profound legacy in Japanese law.

2.3. Contribution to Commercial Code

In addition to his pivotal role in the Civil Code, Ume Kenjirō also played a significant part in the drafting of the Japanese Commercial Code. He collaborated on this endeavor with other prominent legal figures, including Tabu Kaoru and Okano Keijirō. His involvement ensured that the commercial legal framework also aligned with the modern legal principles being established in Japan.

2.4. Public Service Roles

Ume Kenjirō held numerous influential positions within the Japanese government and academia. In 1892, he served on the Civil and Commercial Code Enforcement Investigation Committee, which was chaired by Saionji Kinmochi. He became Dean of the Tokyo Imperial University Faculty of Law in 1897. The same year, he was appointed Chief of the Cabinet Legislative Bureau and concurrently Head of the Cabinet Pension Bureau. He also chaired the Higher Civil Service Examination Committee from 1897 to 1898 and served as a Councillor of the Law Association in 1897. In 1900, he took on the role of General Affairs Chief for the Ministry of Education. These diverse roles underscore his significant influence across legal, educational, and administrative spheres in Meiji Japan.

2.5. Legal Work in Korea

In 1906, Ume Kenjirō's expertise extended beyond Japan when he was asked by Itō Hirobumi, then the Resident-General of Korea (during the period of the Japanese protectorate), to serve as the supreme legal advisor to the Korean government. In this capacity, he contributed to the codification of laws for the Korean government, playing a direct advisory role in the development of its legal framework.

3. Hosei University Contributions

Ume Kenjirō's instrumental role in the establishment and development of Hosei University marks a significant chapter in his legacy.

3.1. Founding of Tokyo Law School

Ume Kenjirō was one of the key figures involved in the establishment of the Tokyo Law School in 1894, which later became Hosei University. Initially, he was hesitant to teach at private institutions, preferring to focus solely on his duties at Tokyo Imperial University. However, he was persuaded by Satta Masakuni, the founder of Hosei University, and his colleagues, particularly Tomii Masaaki and Motono Ichirō, who personally urged him to join. In 1890, he accepted the concurrent position of Academic Supervisor (学監) at Wafutsu Law School, the precursor to Hosei University. By 1899, he assumed the role of Principal (校長) of the school.

3.2. Leadership and Development of Hosei University

From 1903 until his death in 1910, Ume Kenjirō served as the first President (総理SōriJapanese) of Hosei University. He was the only person to be referred to as "Sōri" in the university's history; subsequent leaders were titled "Gakuchō" (President) and later "Sōchō" (Chancellor). Over two decades, his leadership as Academic Supervisor, Principal, and President was instrumental in the establishment and significant development of Hosei University, guiding its growth and educational direction during its foundational years. His commitment ensured the institution's solid academic footing and its lasting contribution to legal education in Japan.

4. Academic Thought and Writings

Ume Kenjirō's legal theories, his approach to legal interpretation, and his extensive published works demonstrate his profound impact on Japanese legal scholarship.

4.1. Legal Philosophy and Interpretation

Ume Kenjirō generally supported a "new natural law theory" that drew influences from figures like Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, and he had a strong affinity for French jurisprudence. He was notably influenced by the French exegetical school, which, while rooted in natural law principles, emphasized that enacted law, reflecting the general will, constituted natural law. For this school, legal interpretation revolved around discovering the legislator's intent and systematically annotating the legal code. However, Ume was a practical scholar who disliked deep philosophical idealism. His focus was on swiftly achieving substantively appropriate legal solutions within the framework of enacted law.

Hozumi Nobushige critiqued Ume's natural law approach, suggesting that by seeking the basis of natural law within existing legal provisions, it deviated from a "true" natural law. Ume himself often used the term "ideal law" instead of "natural law," yet some critics suggested his approach was fundamentally similar to Friedrich Carl von Savigny's pursuit of eternal legal principles rooted in Roman law.

Despite being often associated with the French legal tradition, Ume Kenjirō's views on legal interpretation were more complex. He explicitly stated that for the drafting of the Japanese Civil Code, the German Civil Code draft served as the most crucial model, not the French Civil Code. He also observed that the French Civil Code, being a century old and less complete, meant that its interpretative methods were not fully transferable to the Japanese context. He noted that the general approach to private law interpretation in Japan at the time aligned with the views of German legal scholars like Bernhard Windscheid and Heinrich Dernburg. However, Ume also expressed favor for French legal systems and used the Spanish Civil Code as an example, thereby refuting the common perception that the Japanese Civil Code was merely a copy of German law. This nuanced stance highlights his eclectic approach, drawing from various European legal traditions to shape modern Japanese jurisprudence.

4.2. Major Works and Scholarly Impact

Ume Kenjirō authored a voluminous body of legal works that significantly influenced Japanese legal scholarship and practice. His doctoral dissertation, De la transactionFrench, was a landmark publication. His other key single-authored books include:

- Japanese Sales Law (1891)

- Civil Law: Law of Secured Claims (1892-1893)

- Revised Commercial Law: Company Law, Negotiable Instruments Law, Bankruptcy Law (1893)

- Outline of Company Law (1894)

- Essentials of Civil Law (5 volumes, 1896-1900), a seminal work.

- Civil Law Lecture (1901)

- Outline of Bankruptcy Bill (1903)

- Principles of Civil Law (2 volumes, 1903-1904)

- Recent Case Criticisms (1906, continued in 1909), offering analysis of contemporary legal precedents.

- Civil Law General Provisions (1907)

- Civil Law Principles: General Provisions on Obligations (1992, posthumous publication)

- Civil Law (Meiji 29) Obligations (3 volumes, 1996, posthumous publication)

- Japanese Civil Law Reconciliation Theory (2001, posthumous publication)

- Japanese Civil Law Evidence Chapter Lecture (2002, posthumous publication)

- Japanese Commercial Law (Meiji 23) Lecture (2005, posthumous publication)

- Civil Law Obligations Chapter 2 to 5 (2023, posthumous publication)

He also co-authored Japanese Commercial Law Interpretation (5 volumes, 1890-1893) with Motono Ichirō and Opinion on Code Enforcement (1892). Additionally, he edited Legal Dictionary (3 volumes, 1903-1906). His complete works have been compiled and published in a CD-ROM edition in 2003, underscoring the enduring relevance and breadth of his scholarly contributions to Japanese law.

5. Personal Life

Beyond his professional accomplishments, Ume Kenjirō's personal life was marked by notable family connections and distinctive characteristics.

5.1. Family and Relatives

Ume Kenjirō married Kaneko, the third daughter of Matsumoto Rizaemon, a retainer of the Matsue Domain, who was also a distant relative of the Ume family. After fifteen years of cohabitation, they officially registered their marriage in 1905. The couple had several children:

- His eldest daughter, Ume, later married Itakura Sōichi, an architect and the eldest son of Itakura Matsutarō.

- His eldest son, Midori (1893-1937), dropped out of the English Literature Department at Tokyo Imperial University. Due to his parents not being officially married at his birth, he was initially registered as his maternal grandfather's child before being formally adopted into Ume Kenjirō's family register. His engagement to Itakura Matsutarō's third daughter, Umeko (who was his son-in-law's sister and Ume Kenjirō's adopted daughter), was later dissolved when Midori married his maternal cousin.

- His second son, Shin (1896-1970), graduated from the Tokyo Imperial University Faculty of Law. He worked for the Manchukuo Central Bank and was involved in its post-war liquidation. After returning to Japan, he served as president of Akita Lumber. His wife, Fumiko, was the granddaughter of Hiraoka Kōtarō and Saigō Tsugumichi.

- His third son, Toku (1897-1958), was a twin. He worked as a proofreader for Iwanami Shoten after dropping out of the elective course in the Literature Department at Tokyo Imperial University. He tragically died due to two separate traffic accidents.

- His fourth son, Hikari (born 1897), Toku's twin, graduated from Kyoto Imperial University's Faculty of Law and Economics. He initially ran a publishing company with his brother Toku, then worked for a company in Yokohama before moving to Taiwan and Manchuria.

Through his wife Kaneko, Ume Kenjirō was also related to Lafcadio Hearn's wife, Setsu (Kaneko's maternal uncle's wife and Setsu were cousins). This connection led Ume to become a confidant to Lafcadio Hearn when Hearn was dismissed from Tokyo Imperial University in 1903 (a position later filled by Natsume Sōseki). When Hearn died in September 1904, Ume Kenjirō served as the chairman of his funeral committee.

5.2. Anecdotes and Personal Traits

Ume Kenjirō was renowned for his extraordinary memory and sharp intellect. During his time at the Judicial Ministry Law School, he famously memorized a 300-page French textbook within a week and reproduced it flawlessly in an examination. This feat was so astonishing that it led to a grade reduction by his instructors, who considered it to be beyond human capability. Similarly, he had memorized every single article of the Japanese Civil Code.

At the University of Lyon, his academic excellence was so profound that other Japanese students reported feeling awe and caution from local students, who believed that "Japanese people have legal deities like Tomii and Ume." He was granted the privilege to take his final examination after only three and a half years of study, rather than the usual five. During this exam, he astounded his professors by flawlessly reciting a three-page dissertation verbatim in fluent French, a demonstration of memory that left them in disbelief.

In his personal habits, Ume Kenjirō harbored a notable fondness for unagi (eel). This preference was so strong that eel dishes became a customary meal at Hosei University board meetings. When he traveled to Korea to advise the government, the expenses for eel at the Resident-General's office significantly increased, reflecting his consistent culinary delight.

6. Death and Legacy

Ume Kenjirō's sudden death marked the end of a prolific career, but his profound impact on Japanese law and education continues to be recognized.

6.1. Death

Ume Kenjirō died suddenly in Keijō (present-day Seoul, Korea) on August 25, 1910, at the age of 50. The cause of his death was typhoid fever. His funeral was held as a Hosei University funeral at Gokoku-ji temple in Tokyo, where he is interred.

6.2. Honors and Historical Significance

On August 25, 1910, the very day of his death, Ume Kenjirō was posthumously awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, First Class, one of Japan's highest honors. He had received various other accolades throughout his career, including:

- Junior Seventh Rank (1891)

- Junior Sixth Rank (1894)

- Senior Sixth Rank (1896)

- Senior Fifth Rank (1897)

- Junior Fourth Rank (1900)

- Senior Fourth Rank (1906)

- Junior Third Rank (1910)

- Order of the Rising Sun, Third Class, with Cordon (1898)

- A set of gold cups (1903)

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, Second Class (1906)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (1907)

He also received foreign decorations, including the Officier de l'Instruction Publique (Officer of Public Instruction) from the French Third Republic in 1896. From the Korean Empire, he was awarded the Emperor Sunjong's Enthronement Commemorative Medal in June 1908 and the Order of the Eight Trigrams, First Class, in November 1908.

Despite his immense contributions, Ume Kenjirō was not granted the title of danshaku (baron), unlike his fellow Civil Code drafters Hozumi Nobushige and Tomii Masaaki. This is often attributed to his untimely and early death, which prevented his achievements from being fully recognized by the time such honors were typically bestowed. Nevertheless, he is widely celebrated as the "father of the Japanese Civil Code." His unique distinction as the only Japanese legal scholar to be featured individually on a postage stamp in Japan, as part of the Cultural Figures Series, further highlights his unparalleled recognition and historical importance within the nation's legal landscape.