1. Overview

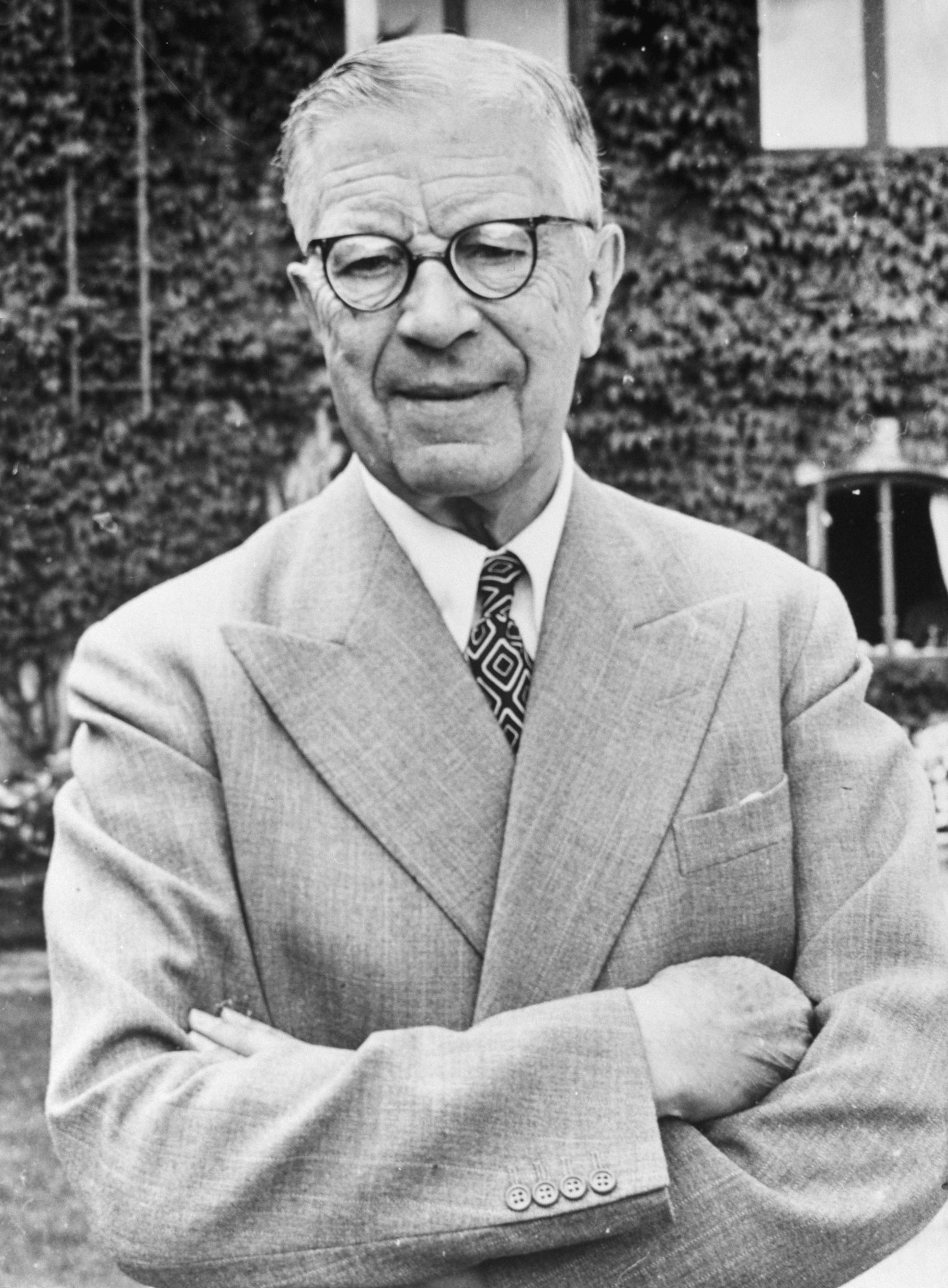

Tage Fritjof Erlander (1901-1985) was a prominent Swedish politician who served as Prime Minister of Sweden and leader of the Social Democratic Party for an unprecedented 23 years, from 1946 to 1969. His tenure is the longest of any head of government in a modern Western democracy. While Urho Kekkonen, President of Finland from 1956 to 1982, served for over 25 years, he was a head of state, whereas Erlander was a head of government. Kekkonen has also been described as an autocrat, distinguishing his leadership from Erlander's democratic context. Erlander played a pivotal role in transforming Sweden into one of the world's most advanced welfare states, solidifying the "Swedish Model" at the height of its international acclaim. Known for his moderation, pragmatism, and self-deprecating humor, Erlander skillfully navigated complex domestic reforms and Cold War foreign policy, often seeking consensus across the political spectrum. He oversaw the implementation of universal health insurance, comprehensive pension additions, and the expansion of the public sector, laying the foundation for a robust social safety net. Despite initial skepticism about his leadership, he became an immensely popular and unifying figure, affectionately known as "Sweden's longest Prime Minister" due to both his height and his enduring time in office. His legacy as the architect of modern Sweden's welfare state continues to be celebrated, though his era has also faced critical scrutiny regarding the perception of Sweden as a de facto one-party state.

2. Life and Education

Tage Erlander's early life was marked by humble beginnings and a strong family background that shaped his worldview, leading him to academic pursuits at Lund University where his political awakening began.

2.1. Early childhood and family background

Tage Fritjof Erlander was born on June 13, 1901, in Ransäter, Värmland County, Sweden, on the top floor of the house now known as Erlandergården, which today serves as a museum. Some biographers have spelled Erlander's middle name as Fritiof or Frithiof. His parents were Alma Erlander (née Nilsson) and Erik Gustaf Erlander, a teacher and cantor. His father, Erik Gustaf Erlander, originally named Erik Gustaf Andersson, later changed his surname to Erlander, a name his son Tage and his descendants retained. Tage had an older brother, Janne Gustaf Erlander (born 1893), an older sister, Anna Erlander (born 1894), and a younger sister, Dagmar Erlander (born 1904).

Erlander's paternal grandfather, Anders Erlandsson, worked as a smith at an ironworks, and his maternal grandfather was a farmer who held a public office in his home municipality. On his maternal grandmother's side, Erlander descended from Forest Finns, who had migrated to Värmland from the Finnish province of Savonia in the 17th century.

The Erlander family was initially poor, though Erik Gustaf supplemented their income by selling homemade furniture and exporting lingonberries to Germany. According to Erlander, his father was deeply religious, a supporter of universal suffrage, pro-free market, anti-trade union, and a liberal. Erlander also noted that his father became increasingly anti-socialist as he aged, speculating that his father was unhappy with his son's eventual election to parliament as a member of a socialist party.

2.2. Education

As a child, Erlander lived on the second floor of Erlandergården and attended school on the first floor. He later attended schools in Karlstad, residing in a boarding house for children of clergymen, and was reportedly a good student in high school.

From 1921 to 1922, Erlander completed his mandatory military service at a machine gun factory in Malmslätt, eventually becoming a reserve Lieutenant in the Signal Corps. In September 1920, his father enrolled him at Lund University instead of Uppsala University, as Lund was considered more affordable. As a student at Lund, Erlander became heavily involved in student politics and encountered many politically radical students. He was exposed to societal and economic injustices, which led him to identify with socialism. Beginning in the autumn of 1923, Erlander read the writings of Karl Marx. He met his future wife, fellow student Aina Andersson, and they began working together in the chemistry department in 1923. He also studied natural sciences with Torsten Gustafson, a future physicist who would later advise Erlander on nuclear affairs during his premiership. In addition to his scientific studies, Erlander also studied economics and was an active member of Wermlands Nation, where he was elected Kurator (head executive) in 1922. In 1926, he led student opposition to celebrations of the 250th anniversary of the Battle of Lund. He graduated in 1928 with a degree in political science and economics.

From 1928 to 1938, Erlander's first major job was as a member of the editorial staff of the encyclopedia Svensk uppslagsbok. In 1930, Tage and Aina married, despite both stating their opposition to the institution in his memoirs. They spent their first few years of marriage apart, with Erlander working in Lund and Aina in Karlshamn, seeing each other only on holidays. Their first son, Sven Bertil Erlander, was born on May 25, 1934, in Halmstad, and their second son, Bo Gunnar Erlander, was born in Lund on May 16, 1937.

3. Early Political Career

Tage Erlander's early political career saw his entry into the Social Democratic Party, his rise through local and national government, and his significant contributions to social policy and educational reform before he unexpectedly became Prime Minister.

3.1. Entry into politics and local government activity

Erlander joined the Social Democratic Party in 1928 and was elected to the Lund municipal council in 1930, serving until 1938. During his time on the council, he focused on improving poor city housing, lowering unemployment, and installing a new public bathhouse, demonstrating his early commitment to urban social welfare.

3.2. Member of Parliament and State Secretary

In 1932, Erlander was elected as a member of the Riksdag (parliament), representing Fyrstadskretsen until 1944. During this period, he began to forge important political connections, notably attracting the attention of Gustav Möller, a prominent Social Democratic politician and then Minister for Social Affairs. In 1938, Möller appointed Erlander as a state secretary at the Ministry of Social Affairs, leading Erlander and his family to relocate to Stockholm.

As a state secretary, Erlander became one of the most senior officials involved in the establishment of internment camps in Sweden during World War II. These camps were set up to house and detain refugees and foreigners, interned German and Allied military personnel, and to conscript pro-Soviet Communists and others deemed unreliable into work camps for infrastructure development, rather than military service. While Erlander later downplayed his knowledge of these camps in his memoirs, he was integral to their design and function, according to journalist Niclas Sennerteg. In 1941, Sweden's Population Commission was created under Erlander's leadership, where he served as chairman, putting forward proposals for grants and regulations concerning daycare centers and play schools. In 1942, Erlander and Möller initiated a nationwide census of the Swedish Travelers, a branch of the Romani people, with the stated purpose of protecting lower-class Swedes and solidifying a leftist base, though such lists in Norway were known to fall into Nazi hands during the occupation.

3.3. Minister in Hansson's government

Erlander joined Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson's World War II coalition cabinet in 1944 as a minister without portfolio, a position he held until 1945. Following the 1944 Swedish general election, he began representing Malmöhus County in the Riksdag.

In the summer of 1945, as part of Hansson's post-war cabinet, Erlander became minister of education and ecclesiastical affairs. It is suggested that he was chosen for this role due to his lack of prior experience with educational policies, which meant he was not associated with existing factional divides over Sweden's educational system. Despite initial skepticism about accepting the role, he grew accustomed to it, even though his tenure was brief.

Erlander largely delegated ecclesiastical matters to other politicians, focusing instead on tangible educational reforms. Influenced by his experiences at Lund University, he advocated for greater investments in research and higher education. He was a significant force behind successful legislation that provided free school lunches and textbooks. On October 29, 1945, Erlander met with Austro-Swedish nuclear physicist Lise Meitner to discuss Sweden's investment in nuclear physics and technology following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In 1946, Minister Möller introduced a new uniform pension proposal aimed at lifting all pensioners above the poverty line, which Erlander and Minister for Finance Ernst Wigforss opposed, but it ultimately passed in the Riksdag.

At the 1945 Social Democratic party conference, a motion to update Swedish schooling was presented, leading to a request for a special committee to develop school programs. This committee was divided on the issue of separating students by abilities, known as streaming, but drafted a proposal for nine years of universal mandatory education. In 1946, Erlander, as minister of education, created a second committee, the Schools Commission, which he chaired. This committee, composed mainly of appointed party members, also proposed nine years of mandatory schooling by 1948, although the debate over streaming continued.

4. Premiership and Party Leadership

Tage Erlander's 23-year tenure as Prime Minister and leader of the Social Democratic Party was a transformative period for Sweden, marked by extensive domestic reforms, a unique approach to Cold War neutrality, and significant political events.

4.1. Succession to Prime Minister and Party Leadership

The sudden death of Prime Minister Per Albin Hansson on October 6, 1946, unexpectedly propelled Erlander to leadership. Foreign Minister Östen Undén was appointed interim prime minister while a successor was chosen. Erlander and his wife were in Lund when Hansson died and were informed upon their return to the Grand Hôtel by Minister of Defense Allan Vougt.

On October 6, Hansson's cabinet and the Social Democratic executive committee met, scheduling a full board party meeting for October 9, as did the Social Democratic party caucus. Erlander first learned of his potential selection as prime minister and party leader on October 7. He was initially reluctant and had little interest in the position, stating he would only accept if the party's desire was strong enough.

At the October 9 meeting, the board voted 15 to 11 in favor of Erlander becoming prime minister, and the caucus voted 94 to 72 to make him party leader. This choice was considered surprising and controversial, as many, including Gustav Möller (who received the remaining 72 votes), believed Möller was Hansson's obvious successor. Erlander's selection has been attributed to younger party members' desire for a new generation of leadership and his perceived ability to foster cooperation between differing views. While there is no written confirmation, some verbal evidence suggests Hansson might have supported Erlander as his successor; for instance, his wife Sigrid claimed Hansson stated shortly before his death, "Now I know who is going to succeed me. It will be Tage Erlander."

Upon meeting Erlander at Drottningholm on October 13 and asking him to form a new government, King Gustaf V encouraged him, stating that a younger man was best for Sweden during difficult times and that they would get along, unlike the king's initial disagreements with the republican Hansson. Erlander asked all cabinet members to withdraw their resignations, thereby retaining Hansson's cabinet. In the two years leading up to the 1948 election, Erlander actively toured the country, visiting numerous Social Democratic organizations to solidify his support and explain party policies. Within his first 365 days in office, he made between seventy and eighty public appearances outside of Stockholm. While Social Democratic newspapers praised his speaking events, non-socialist newspapers initially dismissed him as irrelevant before criticizing him as an unreliable tactician. These perceived attacks inadvertently increased Erlander's popularity within the party.

4.2. First Cabinet (1946-1951)

Erlander's first cabinet largely consisted of ministers inherited from Hansson, totaling 14. He generally granted his cabinet ministers significant freedom, preferring not to be overly involved in daily coordination but maintaining oversight. Over his premiership, Hansson's original ministers gradually left the government. Minister of Commerce Gunnar Myrdal implemented policies such as selling machinery to the Soviet Union on a fifteen-year credit and a 17% appreciation of the Swedish krona. The former was seen as economically unattractive post-war due to stronger trading partners, and the latter worsened Sweden's trade deficit. Due to public backlash, Myrdal resigned in 1947, becoming the first minister to leave Erlander's government. Erlander appointed Josef WeijneSwedish to replace him as minister of education and ecclesiastical affairs.

In 1947, Karin Kock made history as the first woman in Sweden to hold a cabinet position, serving as a minister without portfolio before becoming minister of supply in 1948. Her appointment was suggested by Riksdag member Ulla Wohlin, who would later serve in Erlander's third cabinet. Kock left her post in 1949, and the Ministry of Supply was abolished the following year. When Weijne died in office in 1951, Erlander appointed Hildur Nygren as his successor, making her the second woman to become a cabinet minister in Sweden.

Leading into the 1948 Swedish general election, his first as party leader and prime minister, many Social Democrats, including Erlander's future protégé Ingvar Carlsson, anticipated a loss. The Liberal People's Party, led by Bertil Ohlin, was emerging as a major opposition force. Although Ohlin had served as Hansson's minister of commerce during the wartime coalition, he had opposed Hansson's social policy proposals. During Erlander's government, Ohlin generally supported many Social Democratic policies, but Erlander, still influenced by Ohlin's past opposition, harbored a strong dislike for the Liberals and their leader. Erlander frequently attacked the Liberals in speeches and Riksdag debates, accusing them of irresponsibility, opportunism, and irreconcilability. Their political rivalry is considered one of the most notable in modern Swedish history. Despite these tensions and internal fears, the Social Democrats won 46.13% of the vote, securing 112 out of 230 seats in the Andra kammaren (lower house) of the Riksdag. The Liberals came in second with 22.8%, one of their largest victories. Erlander himself was elected as a representative of Stockholm County after four years representing Malmöhus County. Following this election, the Social Democrats remained in power. To secure a long-term majority, they informally offered to form a coalition government with the Centre Party (then known as the Farmers' League, also previously the Agrarian Union or Agrarian Party, until 1957), but the offer was declined. This did not, however, impede Erlander's ability to form a government on time.

4.3. Coalition Government (1951-1957)

In 1951, Erlander formed a coalition government with the Centre Party, adding four Centrists to his cabinet. His working relationship with the Centre Party's leader, Gunnar Hedlund, was notably good. Despite some ideological differences, Erlander and Hedlund shared a common goal of outmaneuvering the Liberals and the Moderate Party (then the Right Party until 1969). The voter bases of both parties were also considered similar, with the Social Democrats rooted in the working class and the Centre Party among farmers and rural populations. Under the coalition, Hedlund became minister for home affairs.

One of the positions the Centrists demanded was the Minister of Education, which had been held by Hildur Nygren since earlier that year. Erlander used these negotiations as an opportunity to remove Nygren, with whom he did not get along. The coalition government was officially formed on October 1, 1951.

In the 1952 Swedish general election, the Social Democrats' vote share slightly decreased to 46%, while the Centrists also saw a decrease to 10.7%. The Liberals, however, gained, reaching 24.4%.

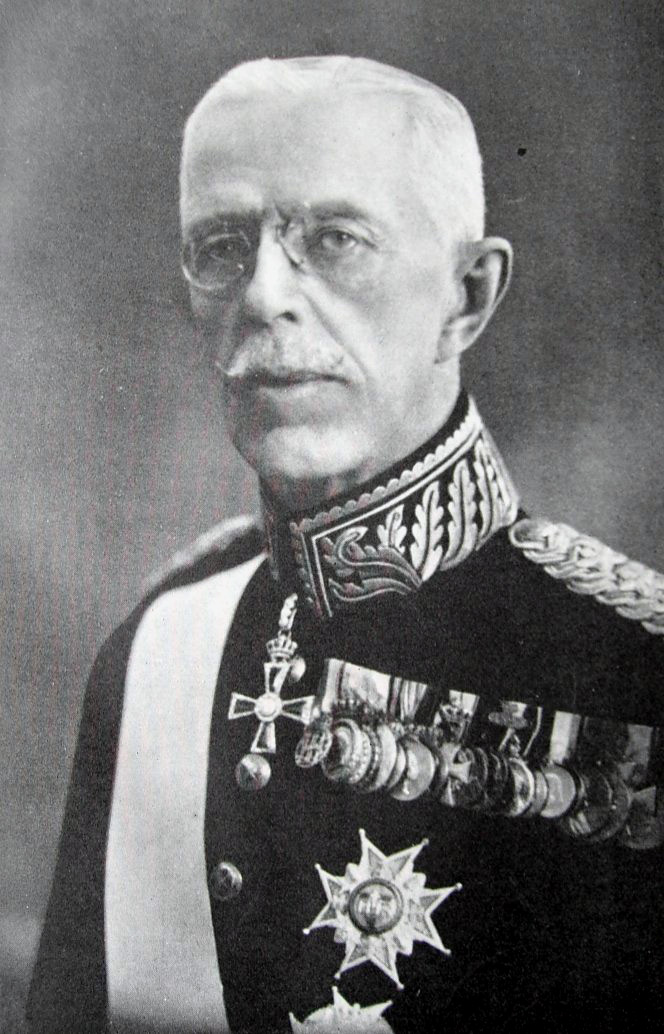

Erlander served under King Gustaf V for four years, and the two shared mutual respect. Gustaf V, who was 88 when Erlander became prime minister, was not very politically active. In 1950, upon his father's death, Crown Prince Gustaf VI Adolf ascended to the throne. Erlander was also on good terms with Gustaf VI, though he occasionally disapproved of the new king's more hands-on involvement in political matters compared to his father. During Gustaf VI's time as Crown Prince, Erlander had viewed him as a "rather stiff individual who lacked perspective."

In 1947, the Haijby scandal erupted when Kurt Haijby, who had been arrested multiple times on suspicion of homosexual acts, wrote a memoir claiming a sexual relationship with Gustaf V. The Stockholm police purchased most of the memoir's stock to prevent its distribution, and the government took charge of the affair. Erlander reportedly believed the allegations and later confided to journalist Maria SchotteniusSwedish that he was tormented for decades by the "Haijbyskiten" (Haijbyskiten"Haijby shit"Swedish).

In the 1956 Swedish general election, the Social Democrats' vote share decreased further to 44.58%. Erlander attributed this setback, in part, to "Christian anti-socialist agitation." Their coalition partners, the Centrists, garnered 9.45%.

Despite the ideological similarities between the Social Democrats and the Centrists, a major point of contention was Sweden's proposed pension system. Erlander advocated for a mandatory system for all citizens, while Hedlund preferred a voluntary one. A 1957 Swedish pensions system referendum was held, offering three proposals: one from the Social Democrats, one from the Centrists, and one from the right-wing parties. The Social Democrats' proposal won with 45.8% of the vote, while the right's garnered 35.3% and the Centrists' 15%. As a direct result of the referendum, the coalition dissolved that year. The king attempted to facilitate a four-party coalition with the three non-socialist parties, appointing Erlander as formateur/informateur. However, Erlander was reluctant, and when the Liberals and Moderates were designated formateurs, the Centrists refused to join, leading to the failure of a non-socialist government. Consequently, Erlander remained prime minister, leading a minority government into the next election.

4.4. Final Government (1957-1969)

By the end of Erlander's premiership, nine of the ten cabinet ministries he inherited from Hansson's cabinet still existed, and three additional ministries had been created, bringing his final cabinet to twelve ministries by 1968. In total, 57 individuals served in Erlander's cabinets throughout his long tenure.

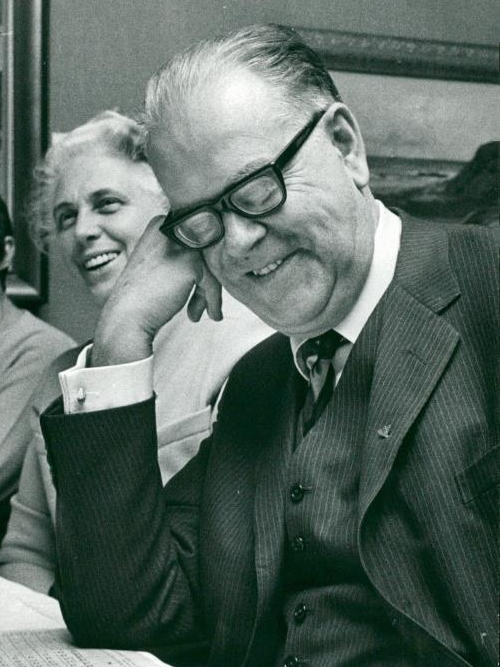

In August 1953, Erlander hired Olof Palme to serve as his personal secretary. Palme would later ascend to the cabinet as a minister without portfolio in 1963, become Minister of Communications in 1965, and then Minister of Education in 1967. Starting with Palme, Erlander began to hire a larger group of young Social Democratic personal staff, including typists and stenographers, such as Ingvar Carlsson and Bengt K. Å. Johansson. In the 1960s, Erlander affectionately referred to this group of young aides as "the boys." Erlander frequently consulted "the boys" on speeches, though he was reportedly rarely satisfied with their drafts, according to Olle SvenningSwedish.

Social Democratic efforts for a universal pension system continued after the 1957 referendum. In 1958, a bill proposing uniform, state-administered pensions for all Swedes over the age of 67 was put to a vote. Left-wing parties supported it, while right-wing parties opposed it. The bill was defeated in a vote of 117 against to 111 for. Following this defeat, Erlander asked the king to temporarily dissolve the Riksdag and called for a snap election. In the ensuing election, the Social Democratic party won 46.2% of the vote, an increase from the 1956 election. This marked the third, and as of 2024, last snap election in Swedish history. In the spring of 1959, the Social Democratic pension system was again voted on in the Riksdag. In the second chamber, the vote was evenly split, 115 for and 115 against. Ture Königson, a Liberal, cast the decisive vote in support of the Socialists' proposal. Königson preferred his party's pension plan but prioritized a secure future for Sweden's older workers, believing the Socialists' plan was better than a permanent political stalemate. Through this narrow margin, the pension plan passed. The system, called Allmän tilläggspension (Allmän tilläggspension"General supplementary pension"Swedish) or ATP for short, was successfully implemented in 1960.

In the 1960 Swedish general election, the Social Democrats' vote share further increased to 47.79%. Erlander described this election as an "ideological breakthrough" that paved the way for further reforms.

On June 20, 1963, Col. Stig Wennerström was arrested on his way to work and charged with espionage. He soon admitted to spying for the Soviet Union for 15 years, and it was later estimated that he had sold around 160 Swedish defense secrets to the Soviet government. Minister of Defence Sven Andersson had been informed of suspicions against Wennerström four years prior and had become personally suspicious two years earlier, as had Foreign Minister Undén. Erlander, however, was not aware of the suspicions until the day Wennerström was arrested. Foreign Minister Torsten Nilsson, Undén's successor, informed Erlander via telephone while he was on vacation in Italy with his wife, asking him to return immediately. Upon returning to Sweden, in response to criticism over the lack of government coordination, Erlander stated on television that "It is impossible for the government to be informed of every person who is under suspicion. We need more proof in a democratic society before we can take action." It later surfaced that twice in 1962, meetings were scheduled with Erlander to discuss Wennerström, but both were canceled due to illness or Erlander's full schedule. Opposition parties demanded a parliamentary investigation, with Bertil Ohlin leading the push for the censure of Sven Andersson and Östen Undén for negligence. In 1964, after two days of debate in the Riksdag, Andersson was not found guilty of gross negligence, and Ohlin dropped plans for a vote of censure. Simultaneously, the lower chamber voted 116 to 105 to clear Undén of negligence charges. Erlander stated that he would regard votes of censure as a question of confidence in his entire cabinet, and that it was "a tragedy" that Wennerström's arrest and trial became a political issue. Also in 1964, Wennerström was found guilty on three counts of gross espionage, stripped of his rank, and ordered to pay the government 98.00 K USD of the 200.00 K USD he was paid by the Soviet government. He was sentenced to life imprisonment but was pardoned and released in 1974. The entire arrest, trial, investigation, and scandal consumed much of Erlander's energy for almost a year.

In the 1964 Swedish general election, the Social Democrats won 47.27% of the vote, a slight decrease from 1960, but the party now secured a majority in the second chamber. The Social Democratic campaign slogan was, "You never had it so good." The Left Party (known as the Communist Party until 1967, when they changed their name to Left Party - The Communists, and in 1990 to their current name) made significant gains that year, winning 3 new seats in the second chamber (in addition to their previous 5) and being the only party to increase their percentage from the previous election.

In a 1955 Swedish driving side referendum, a proposal to switch Sweden from left-hand driving to right-hand driving was overwhelmingly rejected by voters, with 82.9% voting no and only 15.5% in support, though voter turnout was considered low. Despite the public's rejection, efforts continued into the next decade. In 1963, the Riksdag voted by a majority to switch traffic to the right side. In response to public backlash, Erlander stated, "The referendum was only advisory, after all." Following the 1963 Riksdag vote, the project, known as Dagen H, began. Olof Palme, then Minister for Communications (Transport), oversaw the project, which aimed to align Sweden with driving standards in most of Europe. Debates were held, with proponents arguing the change would reduce traffic accidents. A massive advertising campaign was conducted to shift public opinion. On September 3, 1967, Sweden began the drastic change, which required an estimated 360,000 street signs to be changed overnight. The final cost was expected to exceed 800.00 M SEK. Initially, the number of accidents decreased, but by 1969, they returned to pre-1967 levels.

In 1954, Erlander met Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Winston Churchill to discuss different electoral systems. Churchill expressed surprise that Sweden did not use a system of majority voting in single-member constituencies. Erlander explained that such a system would benefit the Social Democrats, to which Churchill famously replied, "A statesman must not hesitate to do the right thing, even if it benefits his own party." In March 1967, Sweden's political parties finally agreed to replace the bicameral Riksdag with a unicameral chamber that would be directly elected. The Första kammaren (upper house) voted to abolish itself on May 17, 1968, with 117 votes for and 13 against. The Riksdag fully became unicameral in 1971, after Erlander had retired from the premiership.

In 1963, actor Yngve Gamlin humorously declared himself president of the Republic of Jamtland, a breakaway state in Swedish territory. In 1967, Erlander invited Gamlin to Harpsund, the prime minister's country retreat. However, when discussions did not go as Gamlin hoped, he stole the plug from Erlander's boat, the HarpsundsekanSwedish.

In the 1968 Swedish general election, Erlander's final election as prime minister, his party achieved its largest victory under his leadership, winning 50.1% of the vote and securing an absolute majority. This was the last bicameral election in Sweden.

4.5. Popularity and public image

Erlander's initial ascent to the premiership was somewhat controversial, partly because he was not considered an obvious successor to Per Albin Hansson. When he became prime minister, many Swedes were unfamiliar with him, and he was often seen as being in Hansson's political shadow during the early years of his premiership. He was both praised and criticized for being a university graduate; critics felt he had not risen through traditional working-class ranks like Hansson. Liberal newspapers were optimistic, viewing his education and administrative experience as beneficial. His youth also sparked both praise and concern; while seen as a figure who could bring new energy with stronger left-leaning ideals, his being younger than several cabinet members raised fears about his ability to maintain party unity.

Despite initial concerns about party instability, Erlander increasingly became known as a unifying figure within his party throughout his premiership. He was viewed as a centrist who would occasionally employ both left-leaning and right-leaning policies, though the party as a whole moved further to the left. Erlander's nationwide support was strongest in the 1960s. While his "unpleasant" voice was criticized during radio broadcasts, his popularity surged with the rise of television, where his amiable and humorous personality shone through. Historian Dick Harrison points to a 1962 appearance on Lennart Hyland's popular talk show Hylands hörna, where Erlander told a humorous story about a priest, as the beginning of his widespread public appeal. His rising popularity was also attributed to an increased emphasis on his poverty-ridden childhood and less on his university education, enhancing his image as a "man of the people."

Erlander's debating style was controversial and criticized by many, including writer Stig AhlgrenSwedish. During debates, Erlander often shifted between serious and comical tones, frequently frustrating his opponents who struggled to keep pace.

In 1967, when standard public opinion polls began in Sweden, Erlander's approval within the Social Democratic Party was 65% in February, rising to 77% in November of that year, and reaching 84% in May 1968. After the 1968 Swedish general election, his approval within the party reached 95%. In 1969, 54% of the general population approved of him as prime minister, while 80% approved of his leadership of the Social Democratic Party.

Erlander earned several nicknames during his tenure. He became known as "Sweden's longest Prime Minister," referring to both his physical stature (76 in (192 cm)), tying him with Carl Bildt (Prime Minister from 1991 to 1994) as the tallest Swedish prime minister, and his record 23-year tenure (the Swedish word långSwedish means both 'long' and 'tall'). Political cartoons often exaggerated his height. By the 1960s, he was affectionately referred to simply as "Tage" within the Social Democratic Party, similar to how Per Albin Hansson was known as "Per Albin."

4.6. Resignation and succession

On October 1, 1969, Erlander resigned as prime minister at the age of 68, with the Social Democrats holding an absolute majority in the second chamber since 1968. He was succeeded by his 42-year-old protégé and friend, Olof Palme. Although Palme was considered more radical and controversial, he had been Erlander's student and was endorsed by him. When asked when Erlander first hinted at him as a successor, Palme stated, "It never happened." However, prior to the announcement, President of Finland Urho Kekkonen asked Erlander about his successor, and when Erlander did not give a concrete answer, Kekkonen asked if it would be Palme. Erlander reportedly responded, "Never, he is far too intelligent for a Prime Minister."

5. Domestic Policy

Under Tage Erlander's leadership, Sweden underwent profound domestic transformations, characterized by the expansion of its welfare state, strategic economic management, and significant social reforms that laid the groundwork for modern Swedish society.

5.1. Welfare State Development

Under Erlander, the central pillars of the Swedish welfare state were enacted between 1946 and 1947, a period often referred to as the Social Democratic "Harvest Time." In these two years, three major reforms were introduced: a basic pension, general child allowances, and sickness cash benefits. To support these initiatives, the National Housing Board was established as the central authority for providing subsidized loans and rent controls, while the National Labor Market Board was created to coordinate nationalized local employment offices and supervise union-controlled but state-subsidized unemployment insurance funds. From 1946 onwards, an extensive system of scholarships and fellowships was provided for higher education, alongside free lunches, school books, and writing materials for all primary and elementary school children.

Erlander coined the phrase "the strong society," which described a society with a growing public sector designed to meet the increasing demand for services generated by an affluent society. The public sector, particularly its welfare state institutions, expanded considerably during his premiership, while nationalizations remained rare. To maintain employment for his large electorate and preserve Swedish sovereignty as a non-NATO member, the armed forces were significantly expanded, reaching an impressive level by the 1960s.

5.2. Housing Policy (Million Programme)

Following World War II, Sweden faced an increasing housing shortage in its larger cities. In response, at the 1964 Social Democratic Party conference, the party adopted the Million Programme, an ambitious plan to construct one million homes within ten years. The proposal successfully passed through the Riksdag in 1965, with the motto, "A good home for everyone."

In 1966, during the early phase of the project, Erlander was famously asked in a debate what a young couple wishing to buy an apartment and start a family in Stockholm should do. He replied, "stand in the housing queue." This was intended as an honest answer, but it proved unpopular, especially as the wait for an apartment in Stockholm was reportedly ten years long. This comment is widely believed to have contributed to Social Democratic losses in the municipal elections that year.

Additionally, critics argued that the Million Programme inadvertently created a form of segregation and that the new housing was visually monotonous. More recent evidence suggests that creating uniformity and separating this housing from more high-quality housing was, in fact, part of the original plan. In 1965, Erlander defended the program against such criticism by arguing that American racial tensions and segregation did not exist and could not be reproduced in Sweden. He stated, "We Swedes live in an infinitely more fortunate situation. The population of our country is homogeneous, not only in regard to race, but also in many other aspects."

Despite these criticisms, the ambitious goal of building one million homes was successfully reached by 1974, with 1,006,000 homes constructed. This achievement largely solved the housing problem at the time, though not entirely. The Social Democrats were eventually able to recover from the municipal election losses.

5.3. Economic Policy

In 1947, a significant tax reform was implemented that reduced income taxes for low-income brackets, introduced an inheritance tax, and raised the marginal tax rate for higher tax brackets. Also in 1947, a special law was passed establishing principles for the construction and operation of homes for the aged.

In 1959, Erlander's government proposed raising the previously lowered income taxes, partly to provide funding for recently expanded welfare programs. Conservative parties opposed this proposal, but the Left Party abstained from voting in the Second Chamber, allowing the proposal to become law.

In 1962, Sweden joined the G10, becoming one of ten countries that agreed to provide an additional 6.00 B USD each in funding to the International Monetary Fund.

In 1964, Erlander's government proposed a new budget set to begin on July 1 of that year. The total budget was 4.86 B USD (in 1964), an increase of 475.00 M USD from the previous budget. The expected deficit was 180.00 M USD, and to prevent it from increasing, Erlander's government proposed ending deductions of old-age pension fees from taxable income. Approximately half of the budget was allocated to welfare-related benefits and programs.

On average, during Erlander's premiership, Sweden's GNP increased by roughly 2.5% per year. It saw a 5% rise in 1963 and 6% in 1964.

5.4. Social Policy

Under Erlander's leadership, Sweden significantly advanced its social policies, laying the foundation for its renowned welfare state. In 1948, a general child allowance was made payable to all persons in Sweden with at least one child under the age of 16. This built upon the introduction of housing allowances for families with children in 1947. In 1954, housing allowances were extended to pensioners, and in 1960, the income-test for the children's pension was abolished.

Educational reforms were also central to his social agenda. In 1950, a ten-year experimental period was established to develop a nine-year compulsory comprehensive school, replacing the old parallel system. A law passed in 1955 provided state subsidies for municipally organized vocational schools, and a 1958 law extended state subsidies to adult education centers. In 1962, a final decision was made to implement the nine-year comprehensive school over a ten-year period. Further educational reforms in 1964 revised upper secondary school and introduced special preparatory vocational schools (fackskolaSwedish) to complement the high school (gymnasium). The same year saw the expansion of higher education, with new decentralized universities and colleges established. In 1967, municipal adult education (vuxenutbildningSwedish) was instituted.

Healthcare and worker protections also saw significant advancements. In 1955, medical insurance that provided earnings-related benefits was introduced. The following year, the Social Democrats sponsored a law on "social help," which further extended social services. A maternity allowance was introduced in 1962, providing a six-month period of paid leave to new mothers. A reform of unemployment benefits in 1968 doubled their maximum duration from 30 to 60 weeks. Additionally, a number of laws concerning vacations, worker's safety, and working hours were introduced, significantly improving living standards and social security.

5.5. Nuclear Weapons Policy

The question of whether Sweden should acquire nuclear weapons as a means to deter a possible attack remained a divisive issue within Swedish society and among Social Democrats, prompting diplomatic agreements with the United States that guaranteed intervention in the case of an invasion. Erlander was initially in favor of acquiring nuclear weapons for defense but faced considerable criticism for this stance. Following a 1954 report by Supreme Commander Nils Swedlund, who advocated for Sweden acquiring nuclear weapons to maintain neutrality, Erlander sought to avoid public debate on the issue so his party could develop a unified position and then collaborate with the opposition.

However, the Social Democrats became split on the issue, while the Moderates publicly pushed for nuclear weapons. The strongest opposition within Erlander's party came from the Social Democrat Women's Organization (SSKF). The first government meeting on the issue occurred in November 1955, followed by a Social Democratic Party discussion in February 1956. Erlander had his anti-nuclear foreign minister Östen Undén discuss ongoing UN nuclear disarmament talks. Erlander also proposed delaying the decision until 1958, arguing that the government lacked sufficient knowledge about the technical prerequisites for nuclear weapons and that he did not want to complicate disarmament talks by producing nuclear weapons at that time. After Undén's presentation, SSKF chair Inga Thorsson publicly declared her organization's opposition to nuclear weapons, but the party board ultimately followed Erlander's proposed postponement.

During a March 1959 debate in the Riksdag, Erlander implied that he did not want to add to the "limited number of countries" with atomic weapons, pending the results of a nuclear summit. Sweden eventually signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 1968, effectively abandoning any pretense of developing a nuclear weapon. However, some nuclear reactors were kept secret from the IAEA until 1994, and small teams of theoretical physicists continued researching nuclear weapons after Erlander's premiership. Some international observers speculated that Erlander and future Swedish leaders maintained interest in a hypothetical nuclear system for defense, but did not take action to develop one. According to Erlander's memoirs, Swedish military chiefs believed in limited nuclear war, inspired by Henry Kissinger's advocacy of the policy, as it appeared to be a "defense strategy that appeared to be made for a small state's defense."

6. Foreign Policy

During the Cold War, Tage Erlander's foreign policy was defined by Sweden's commitment to neutrality, its complex relationships with major international powers, and its principled stands on global issues.

6.1. Cold War Neutrality and Alliances

Under Erlander's leadership, Sweden navigated the complexities of the Cold War by maintaining a unique foreign policy. While Sweden did not officially align with either the United States or the Soviet Union, its position was often described as "non-alliance" rather than strict "neutrality." Erlander once stated that Sweden shared an "ideological affinity with the Western democracies." Erlander and his foreign minister, Östen Undén, were seen as the leading figures upholding Sweden's firm stance on neutrality.

Erlander represented Sweden at the funerals of several foreign heads of state, including that of United States President John F. Kennedy in 1963 and West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer in 1967.

Negotiations for a Scandinavian defence union began in 1948, with Erlander and Danish Prime Minister Hans Hedtoft being its strongest proponents. However, the proposal ultimately failed and was shelved in January 1949 due to Norwegian resistance and that country's decision to join NATO, with Denmark and Iceland following suit. Despite this, Erlander stated during his 1952 United States tour that Sweden would not join NATO. He was generally considered a pro-Western leader, writing that America was providing a great service to Europe by increasing its arms for defense against the Soviet Union. In 1961, Erlander and President John F. Kennedy advocated for strengthening the United Nations and its Secretary General, Swedish politician Dag Hammarskjöld. Erlander was also a strong supporter of the proposed Nordic economic community Nordek, holding meetings on the subject with Finnish President Urho Kekkonen and Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto in 1969.

6.2. Relations with the United States

In 1952, as part of his U.S. tour, Erlander met United States President Harry S. Truman, marking the first time a Swedish Prime Minister and a U.S. president met. Erlander would later meet Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson.

In 1958, Sweden recognized South Vietnam, establishing diplomatic relations in Saigon in 1960, though without an official ambassador. In the 1960s, Erlander and the Swedish government became increasingly critical of the Vietnam War. Despite Erlander's personal opposition to the war and the uneasy nature of U.S.-Sweden relations at that point, William Womack Heath, the U.S. ambassador to Sweden during the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, found Erlander to be "completely pro-American" from 1967 until early 1968.

However, on February 21, 1968, Olof Palme participated in a torchlight parade through Stockholm with North Vietnam's ambassador to Moscow, Nguyễn Thọ Chân, to protest the Vietnam War. This event significantly soured Swedish relations with the United States and stirred controversy worldwide, leading to Ambassador Heath being recalled for "consultations" without an immediate successor appointed. Moderate leader Yngve Holmberg called for Palme's resignation from the cabinet, but the demand was not met. By March 1968, Sweden had accepted 79 draft-dodgers from the United States, and Erlander, soon followed by opposition party leaders, publicly stated his opposition to the Vietnam War.

6.3. Relations with the Soviet Union

In 1950, Erlander condemned the aggression of North Korea that began the Korean War, deeming it "a deed of violence calculated to imperil world peace." Sweden subsequently dispatched a field hospital to South Korea. In June 1952, during the war, the Soviet Union shot down two Swedish military aircraft in an event known as the Catalina affair.

Erlander and Hedlund planned a visit to the Soviet Union in 1956 to ease tensions, marking the first time a Swedish prime minister visited the country. However, Erlander was prepared to cancel the trip if the Soviet government refused to accept the information the Swedish government had collected on Raoul Wallenberg, a businessman and humanitarian who had served as Sweden's special envoy in Budapest and disappeared after his arrest by Soviet forces in 1945. Since 1952, the Swedish government had demanded Wallenberg's return, but the Soviet Union consistently claimed unfamiliarity with him. During the visit, Erlander questioned Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev about Wallenberg's status, presenting him with a large file of evidence connecting the Soviet Union to Wallenberg's disappearance. Khrushchev examined the file and stated that Swedish-Soviet relations would improve if the Wallenberg affair was dropped. Soviet documents claimed Wallenberg died in a cell in 1947 of a heart attack, but Erlander, the Swedish government, and international observers remained skeptical. Wallenberg biographer Ingrid Carlberg noted that Soviet documents declassified after the fall of the Soviet Union confirmed Wallenberg's presence, which Khrushchev had denied, and that his official Soviet prison card did not specify a crime.

In 1959, Khrushchev planned to visit Scandinavia and Finland, but negative reactions from the Swedish press and opposition led him to "postpone" it. Erlander and Undén expressed disappointment, to which Khrushchev responded in a Moscow speech that the decision was due to the Swedish government's failure to counter the negative press. Erlander stated that the government could not engage in polemics against such opinions, as it would give them undue importance. The government then avoided appointing the anti-Khrushchev Conservative leader Jarl Hjalmarson to Sweden's UN delegation. While traveling for his United States visit, Khrushchev sent Erlander a message of "friendship" to ensure the postponed visit was still possible.

In 1963, following the arrest of Stig Wennerström, Erlander stated that the case had seriously disturbed relations between Sweden and the Soviet Union. Nikita Khrushchev had planned a goodwill tour of Scandinavia in 1964, which was set to begin 10 days after Wennerström's life sentence. Erlander declined to comment on how the sentencing might affect Khrushchev's visit. During that 1964 visit, while hosting Khrushchev at Harpsund, Erlander famously took Khrushchev and his interpreter in an eka rowing boat called the Harpsundseka across the nearby 300-yard lake. This has since become a tradition for Swedish prime ministers and foreign heads of state visiting Harpsund. During this visit, Erlander was again unable to obtain information from Khrushchev regarding Raoul Wallenberg. Khrushchev continued to deny Wallenberg's presence in the Soviet Union, leading Erlander and the Swedish government to express "deep disappointment" over the lack of progress in the case. Anti-Khrushchev protests by Soviet exiles occurred in Sweden during his visit, and the Swedish press criticized him for his statements on Wallenberg and the stringent security (3,000 police officers upon his arrival) surrounding him. Both Khrushchev and Erlander ultimately expressed satisfaction with the visit, and Khrushchev departed for Norway on June 27 as part of his Scandinavian goodwill tour. Khrushchev did not mention the Wallenberg controversy or the negative press in his farewell address. After visiting the Soviet Union in 1965, Erlander stated that the case had to be closed.

In 1968, tensions rose between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union due to Czechoslovakia's implementation of political reforms. The Swedish public expected their government to support Czechoslovakia, given its opposition to the Vietnam War, but the government aimed to maintain neutrality. In July, Soviet politician Alexei Kosygin visited Stockholm, prompting Liberal leader Sven Wedén to deliver a speech rebuking Erlander's perceived neglect of Czechoslovak self-determination. In response, Erlander and Foreign Minister Torsten Nilsson cited a secret report from Agda Rössel, the ambassador in Belgrade, stating that Czechoslovak leaders desired Western silence. Although the government's response was not as strong as it had been to the Vietnam War, when the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia began, Erlander, the Social Democrats, and all opposition parties condemned it. The Social Democrats' opposition to the invasion likely contributed to their electoral success in 1968.

6.4. International Issues and Relations

Sweden, under Erlander, took principled stands on various international issues and maintained diplomatic relations with key nations.

In the 1960s, after Erlander delivered a speech to students at Lund University, South African Lund student and anti-apartheid activist Billy Modise personally requested that Erlander impose sanctions on South Africa in response to apartheid. Erlander stated he did not have the power to do so but advised Modise to publicly lobby for the policy. Olof Palme was also a strong advocate for sanctions against South Africa and became more outspoken on his opposition to apartheid after joining Erlander's cabinet in 1963. The Swedish South Africa Committee was created in 1961, and in 1963, the National Council of Swedish Youth launched a boycott against South African goods. Erlander and Palme were among the sponsors of the committee. Swedish donations to the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa (IDAF) increased significantly. In 1964, Sweden became the first industrialized Western country to donate public funds to the IDAF, contributing the equivalent of 100.00 K USD, ultimately becoming by far the largest donor.

In 1947, Sweden voted in favor of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. In 1948, Sweden recognized Israel, and an embassy was established in Israel in 1951. In 1962, Erlander became the first Swedish prime minister to visit Israel. During his visit, Erlander was famously photographed swimming in the Dead Sea. He met with Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. According to Erlander, no specific policies were discussed, though he hoped the visit would strengthen Israeli-Swedish relations. Erlander stated that he was "fascinated" by the country and invited Premier Ben-Gurion to visit Sweden, which he did later that year.

7. Later Life and Death

After concluding his record-breaking premiership, Tage Erlander transitioned from public office to focus on his memoirs and other public activities, remaining a respected national figure until his passing.

7.1. Resignation and retirement from Parliament

On October 1, 1969, Tage Erlander resigned as prime minister at the age of 68, having led the Social Democrats to an absolute majority in the second chamber in the 1968 election. He was succeeded by Olof Palme, who was 42 years old at the time. Palme, though more radical and controversial, had been Erlander's long-time protégé and was endorsed by him. Palme later stated that Erlander never explicitly hinted at him as a successor. However, Finnish President Urho Kekkonen recalled asking Erlander about his successor, and upon suggesting Palme, Erlander reportedly responded, "Never, he is far too intelligent for a Prime Minister."

After his resignation, Erlander and his wife lived in a house constructed at Bommersvik by the Social Democrats in his honor, owned by the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League. Erlander remained a member of the Riksdag for several years after it became unicameral. Following the 1970 Swedish general election, he changed constituencies, now representing Gothenburg, after 22 years as a Stockholm representative. He finally resigned from the Riksdag in 1973, concluding a parliamentary career that spanned over forty years.

7.2. Memoirs and Public Activities

After leaving his leadership roles, Erlander dedicated himself to sorting through his extensive personal papers, which he used as the basis for his political memoirs. In 1972, he wrote an article for Svenska Dagbladet explaining his motivations for undertaking this project. His memoirs were published in six volumes between 1972 and 1982. In the 1980s, Erlander granted writer Olof Ruin unlimited access to his diaries, which would serve as a primary source for Ruin's biography of Erlander. He continued to speak on political matters even after his retirement.

7.3. Death and Funeral

Tage Erlander died on June 21, 1985, in Stockholm at the age of 84, from pneumonia and heart failure. His passing was met with national mourning. His coffin, draped with a socialist flag and adorned with blue and yellow flowers (the colors of the Swedish flag), was carried through Stockholm. An estimated 45,000 Swedes lined the streets to pay their respects. A large, secular ceremony was held in Stockholm, where Olof Palme delivered Erlander's eulogy. At the end of the service, the audience sang the socialist hymn "The Internationale". Following the Stockholm ceremony, his funeral procession traveled across the country to his hometown of Ransäter, Värmland, in a triumphant procession for his final rest. His wife, Aina, who died in 1990, is buried beside him.

8. Ideology and Political Philosophy

Tage Erlander's political philosophy was rooted in a pragmatic approach to social democracy, emphasizing a strong public sector within a well-regulated capitalist framework, and a nuanced understanding of economic theory.

8.1. Social Democracy and Economic Views

Despite his familiarity with the writings of Karl Marx and his identification as a socialist, Erlander did not subscribe to full Marxism and notably did not support large-scale nationalization. Instead, he believed in fostering a strong public sector under a well-regulated capitalism that incorporated comprehensive social welfare programs. Drawing from his university studies, Erlander believed that Keynesian economics and Stockholm School economics were compatible with social democracy and could be effectively utilized to overcome economic downturns. Unlike many other left-leaning intellectuals of his time, Erlander did not sympathize with the Soviet Union, although he did endeavor to maintain positive Swedish-Soviet relations.

8.2. Pragmatism and Centrist Stance

Erlander was characterized by his moderation, self-deprecating humor, and exceptional skill in building consensus and navigating complex political landscapes. He famously stated that "A politician's job is to build the dance floor, so that everyone can dance as they please," reflecting his belief in creating a framework for societal well-being while allowing individual freedom.

While Erlander acknowledged the need for women to play a larger role in politics and hold cabinet positions, he reportedly had disputes or grievances with all the women who served in his cabinet. He maintained a good relationship with Moderate Party leader Jarl Hjalmarson, though he privately viewed Hjalmarson as a "political lightweight." In 1968, Erlander expressed a hope that the then-Moderate leader Yngve Holmberg would remain in office, attributing this to the disorganization of the opposition parties and Holmberg's perceived "clunkiness." Erlander admired the writings of Adlai Stevenson II, noting that Stevenson "expressed his views more deftly than he could himself."

Ingvar Carlsson stated in 2023 that Erlander was "completely unspoiled by power," noting that while power often corrupts, Erlander taught him to be humble and grateful for the opportunity to enact change.

9. Personal Life

Tage Erlander's personal life was marked by a harmonious family life, disciplined habits, and a deep appreciation for culture, which provided balance to his demanding political career.

9.1. Family and Marriage

Erlander met his future wife, Aina Andersson, while they were both students at Lund University. They married in 1930. Their marriage has been consistently described as "deeply harmonious" and "full of mutual trust," and Erlander's family life was considered "remarkably happy." For their first few years of marriage, they lived apart, with Erlander working in Lund and Aina in Karlshamn, seeing each other only on holidays. Their first son, Sven Bertil Erlander, was born on May 25, 1934, in Halmstad, and their second son, Bo Gunnar Erlander, was born in Lund on May 16, 1937. Sven Erlander later became a mathematician and was instrumental in publishing much of his father's diaries starting in 2001. Erlander's mother, Alma, died in 1961 at the age of 92, during her son's premiership. Through one of Erlander's Finnish ancestors, Simon Larsson (née Kauttoinen) (c.1605-1696), he is a distant relative of Stefan Löfven, the Social Democratic Prime Minister of Sweden from 2014 to 2021.

Carl August Wicander donated Harpsund to the Swedish government in 1953 as a country retreat for prime ministers. Erlander began using it as a vacation home that same year, a practice continued by all subsequent prime ministers. Erlander and his wife frequently spent Christmases, Easters, weekends, and summers vacationing at Harpsund. For most of his career, the Erlander family resided in an apartment in Bromma, Stockholm, until the summer of 1964, when they moved to an apartment in a high-rise complex in Stockholm's Gamla stan (Old Town) district. Earlier in his career, Erlander often traveled by subway to and from work rather than using a car. Eventually, he and Aina purchased a car, and Aina typically drove him to work, as he did not have a driver's license, dropping him off before driving to the school where she worked. When Aina was unable to drive him, neighbors in Bromma often offered him rides. Notably, Erlander did not have an official car for travel, and visiting foreign heads of state were often surprised to see him arrive at events alone.

9.2. Personality, Interests, and Habits

Erlander was known for his disciplined habit of diary writing, often making daily entries. These diaries served as crucial sources for his memoirs. He wrote on a wide variety of subjects, initially using the diaries to help him remember work-related details such as occurrences, arguments, and decisions, going into greater detail on matters he considered controversial. He also recorded observations about his family, his health, plays he attended, books he read, and his impressions of other people. Erlander would later frequently note that his diaries contained many exaggerations.

Erlander was often described as a "fatherly" or "avuncular" figure. Ingvar Carlsson stated that Erlander became like a second father or a guide to him. Biographers Dick Harrison and Olof Ruin noted that although Erlander was in power longer than any other Swedish leader, he didn't seek power for himself, a sentiment affirmed by Carlsson.

Erlander was an avid lover of literature and theatre, which often served as a source of recreation. His favorite novel was John Steinbeck's Cannery Row. Many contemporary Swedish writers were often surprised to learn that their prime minister had read their work. During his premiership, Erlander frequently visited his former college, Lund University, meeting the Värmland Student Association. At one of these meetings, Student Association members Olof Ruin and Lars BergquistSwedish proposed that Erlander should give annual speeches to Lund students, to which Erlander agreed. In total, he gave fourteen of these student addresses.

10. Legacy and Evaluation

Tage Erlander's enduring impact on Sweden is profound, as he is widely regarded as the principal architect of the modern Swedish welfare state. His long premiership shaped the nation's social and political landscape, leaving a lasting legacy in both policy and public perception.

10.1. Architect of the Swedish Welfare State

Erlander served as prime minister for 23 years, making him the longest-serving prime minister in Swedish history. His uninterrupted tenure as head of government is also the longest ever in any modern Western democracy. Two of Erlander's closest advisors, Olof Palme and Ingvar Carlsson, both went on to become prime ministers of Sweden, and together their tenures span more than 40 years.

Erlander has been dubbed a "political giant" who transformed Sweden's political climate and brought the nation together, often compared to other notable Swedish "political giants" such as Palme and Dag Hammarskjöld. Biographer Dick Harrison and journalist Per Olov Enquist have described Erlander as a "father of the country" (landsfaderSwedish). Olof Ruin noted that as Sweden encountered difficulties in the 1970s, nostalgia sometimes influenced positive views of Erlander, with his time as leader being looked upon by some as a "golden age" of Swedish history. During his premiership, despite disagreements between parties, particularly the Liberals and Moderates who supported lower taxes, Sweden's major political parties began to increasingly agree on the fundamental goal of developing Sweden as a welfare state.

10.2. Popular Perception and Influence

Upon his death, The Washington Post described Erlander as "one of the most popular political leaders." He was initially somewhat controversial, partly because he was not considered an obvious successor to Per Albin Hansson, and many Swedes were unfamiliar with him, often seeing him in Hansson's political shadow during the early years of his premiership. He was both praised and criticized for being a university graduate, with critics suggesting he had not risen through traditional working-class ranks like Hansson. However, his youth was also seen as a source of new energy and stronger left-leaning ideals for the party.

Despite initial concerns about party instability, Erlander became increasingly known as a unifying figure within his party throughout his premiership. He was viewed as a centrist who would sometimes utilize both left-leaning and right-leaning policies, though the party as a whole moved further to the left. Erlander's nationwide support reached its strongest point in the 1960s. While his "unpleasant" voice was criticized during radio broadcasts, his popularity surged with the rise of television, where his amiable and humorous personality was more apparent. A 1962 appearance on Lennart Hyland's popular talk show Hylands hörna, where Erlander shared a humorous story about a priest, is often cited as the beginning of his widespread public appeal. His rising popularity was also attributed to an increased emphasis on his poverty-ridden childhood and less on his university education, which improved his image as a "man of the people."

Erlander's debating style was controversial and criticized by many. He was known to frequently shift between serious and comical tones during debates, often frustrating his opponents who struggled to keep pace. When standard public opinion polls began in Sweden in 1967, Erlander's approval within the Social Democratic Party was 65% in February, rising to 77% in November of that year, and reaching 84% in May 1968. After the 1968 Swedish general election, his approval within the party reached 95%. In 1969, 54% of the general population polled showed approval of him as prime minister, while 80% approved of his leadership of the Social Democratic Party.

Erlander garnered a number of nicknames during his tenure. He became known as "Sweden's longest Prime Minister," referring to both his physical stature (76 in (192 cm)) and his record 23-year tenure (the Swedish word långSwedish means both 'long' and 'tall'). Political cartoons often mocked him by exaggerating his height. By the 1960s, he became generally affectionately referred to as "Tage" within the Social Democratic Party, similar to how Per Albin Hansson had become known as "Per Albin."

10.3. Criticism and Historical Evaluation

Some conservative and liberal analysts have argued that during Erlander's premiership, an impression of Sweden becoming a de facto one-party state developed. Critics of Olof Palme have also criticized Erlander for his role in Palme's ascension to the premiership. In general, following Sweden's economic crises in the 1970s, the "Swedish Model," and to some extent Erlander's premiership, faced increased scrutiny. Despite these criticisms, Left Party leader Nooshi Dadgostar praised Erlander in 2022, citing him as an inspiration who passed reforms laying the foundation of Sweden's welfare state.

11. Commemoration and Tributes

Tage Erlander's significant contributions to Sweden are recognized through various commemorations and tributes, preserving his legacy for future generations.

11.1. Erlander House Museum

The building that served as Erlander's childhood home and schoolhouse in Ransäter is now a museum named Erlandergården, dedicated to preserving his legacy and providing insights into his life.

11.2. Tage Erlander Prize

The Tage Erlander Prize, awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, is a prestigious award for research in natural sciences, technology, and mathematics, established in Erlander's name to honor his contributions.

12. Awards

Tage Erlander was a nominee for the 1971 Nobel Peace Prize, though he did not win. In 1984, he was awarded the Illis quorum, a Swedish government medal.

13. In Popular Culture

Tage Erlander's prominent role in Swedish history has led to his portrayal and references in various forms of popular media.

- In the 2013 comedy film The Hundred-Year Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared, Erlander was portrayed by Swedish actor Johan Rheborg.

- In the 2021 series En Kunglig AffärEn kunglig affärSwedish, which depicted the Haijby scandal, Erlander was portrayed by Swedish actor Emil Almén.

- In the 2022 Netflix series Clark, which depicted the life of Swedish criminal Clark Olofsson, Erlander was portrayed by Swedish actor Claes Malmberg.

14. Works

- Erlander, Tage (1959). Levande stad (in Swedish). Stockholm: Raben & Sjögren.

- Erlander, Tage (1961). Arvet från Hammarskjöld (in Swedish). Stockholm: Gummessons Bokförlag.

- Erlander, Tage (1972). Tage Erlander 1901-1939 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Tidens förlag.

- Erlander, Tage (1973). Tage Erlander 1940-1949 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Tidens förlag.

- Erlander, Tage (1974). Tage Erlander 1949-1954 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Tidens förlag.

- Erlander, Tage (1976). Tage Erlander 1955-1960 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Tidens förlag.

- Erlander, Tage (1979). Tage Erlander Sjuttiotal (in Swedish). Stockholm: Tidens förlag.

- Erlander, Tage (1982). Tage Erlander 1960-talet (in Swedish). Stockholm: Tidens förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2001). Dagböcker 1945-1949 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2001). Dagböcker 1950-1951 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2002). Dagböcker 1952 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2003). Dagböcker 1953 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2004). Dagböcker 1954 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2005). Dagböcker 1955 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2006). Dagböcker 1956 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2007). Dagböcker 1957 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2008). Dagböcker 1958 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2009). Dagböcker 1959 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2010). Dagböcker 1960 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2011). Dagböcker 1961-1962 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2012). Dagböcker 1963-1964 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2013). Dagböcker 1965 (in Swedish). Gudlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2014). Dagböcker 1966-1967 (in Swedish). Gidlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2015). Dagböcker 1968 (in Swedish). Gudlunds förlag.

- Erlander, Tage; Erlander, Sven (2016). Dagböcker 1969 (in Swedish). Gudlunds förlag.