1. Early Life and Background

David Ben-Gurion's formative years were deeply influenced by the Zionist and socialist ideologies prevalent in his Polish-Jewish community, laying the groundwork for his future leadership in the movement for a Jewish state.

1.1. Childhood and Education

David Ben-Gurion was born David Grün on 16 October 1886 in Płońsk, then part of Congress Poland within the Russian Empire, to Polish Jewish parents. His father, Avigdor Grün, was a "secret adviser" who helped clients navigate the Imperial legal system and co-founded a Zionist group called Beni Zion (Children of Zion) in 1896, which grew to 200 members by 1900. David was the youngest of three boys, with an older and younger sister. His mother, Scheindel (Broitman), died in 1897 from sepsis after her eleventh pregnancy, a stillbirth. Two years later, his father remarried. A birth certificate found in 2003 indicated he had a twin brother who died shortly after birth.

Between the ages of five and 13, Ben-Gurion attended five different heders, two of which were "modern" and taught in Hebrew rather than Yiddish, as well as compulsory Russian classes. His formal education ended after his bar mitzvah, as his father could not afford to enroll him in Płońsk's beth midrash. At 14, he and two friends formed a youth club called Ezra, promoting Hebrew studies and emigration to the Holy Land. The group ran Hebrew classes for local youth and in 1903 collected funds for victims of the Kishinev pogrom. One biographer estimated Ezra had 150 members within a year, while another suggested the group never had more than "several dozen."

1.2. Early Political Activities

In 1904, Ben-Gurion moved to Warsaw hoping to enroll in the Warsaw Mechanical-Technical School, but lacked sufficient qualifications. He took work teaching Hebrew in a Warsaw heder and, inspired by Tolstoy, became a vegetarian. He became involved in Zionist politics, joining the clandestine Social-Democratic Jewish Workers' Party, Poalei Zion, in October 1905. Two months later, he was the delegate from Płońsk at a local conference. While in Warsaw, the Russian Revolution of 1905 broke out, and he was arrested twice during the subsequent crackdown, once being held for two weeks before being released with his father's help.

In December 1905, he returned to Płońsk as a full-time Poalei Zion operative, working to oppose the anti-Zionist General Jewish Labour Bund and organizing a strike among garment workers over working conditions. He was known to use intimidatory tactics, such as extorting money from wealthy Jews at gunpoint to raise funds for Jewish workers. Ben-Gurion later reflected on his hometown, stating that antisemitic feelings had little to do with his dedication to Zionism, as Płońsk was remarkably free of it. He noted that Płońsk sent the highest proportion of Jews to Eretz Israel from any comparable town in Poland, driven by "the positive purpose of rebuilding a homeland," rather than negative reasons of escape. He described relations between the city's three main communities-Russians, Jews, and Poles-as generally amicable, though distant. In autumn of 1906, he left Poland for Palestine, his voyage funded by his father, traveling with his sweetheart Rachel Nelkin and her mother, and his comrade Shlomo Zemach.

2. Immigration to Palestine and Early Zionist Activities

Ben-Gurion's immigration to Palestine in 1906 marked a pivotal moment in his life, transitioning from a young activist to a practical laborer and a budding leader within the burgeoning Zionist community. His experiences shaped his understanding of the challenges and realities of establishing a Jewish homeland.

Immediately upon landing in Jaffa on 7 September 1906, Ben-Gurion set off on foot with a group of 14 to Petah Tikva, the largest of the 13 Jewish agricultural settlements. He worked as a day laborer, struggling to compete with local villagers who were more skilled and worked for less. He was shocked by the number of Arabs employed and, after catching malaria in November, was advised by a doctor to return to Europe. By summer 1907, he had worked an average of only ten days a month, often leaving him without money for food. He wrote long letters in Hebrew to his father and friends, but rarely revealed how difficult life was, unlike others from Płońsk who wrote of tuberculosis, cholera, and people dying of hunger.

Ben-Gurion was noticed by Israel Shochat, a Poale Zion follower who invited him to the founding conference of the Jewish Social Democratic Workers' Party in Jaffa in October 1906. There, Ben-Gurion was elected to the five-man Central Committee and the ten-man Manifesto Committee, also serving as chairman of the sessions, which he conducted exclusively in Hebrew. The conference was divided between a faction, the Rostovians, who advocated a single Arab-Jewish proletariat, and Shochat and Ben-Gurion, who opposed this. The Manifesto Committee produced "The Ramleh Programme," approved in January 1907, which called for the "political independence of the Jewish People in this country," with all activities in Hebrew, segregation of Jewish and Arab economies, and the establishment of a Jewish trade union. Ben-Gurion also helped establish three small trade unions and the Jaffa Professional Trade Union Alliance with 75 members, and mediated a strike at the Rishon Le Zion winery.

The arrival of Yitzhak Ben-Zvi in April 1907 revitalized local Poale Zion, leading to a conference where Ben-Zvi was elected to the Central Committee and Ben-Gurion's policies were reversed in favor of Yiddish and a united Jewish and Arab proletariat. Ben-Gurion, disappointed, moved to Rishon Lezion and later to Sejera in October 1907. There, he found work on an agricultural training farm where, despite being excluded from the "collective" of Bar Giora, he took turns patrolling the farm at night after a Circassian nightwatchman was sacked, leading to nightly shots being fired. In autumn 1908, he returned to Płońsk to avoid conscription into the Imperial Russian Army, then immediately deserted and returned to Sejera via Germany with forged papers.

In April 1909, two Jews were killed in Sejera during clashes with local Arabs. Later that summer, Ben-Gurion moved to Zichron Yaakov, from where he was invited by Ben-Zvi to join the staff of Poale Zion's new Hebrew periodical, Ha'ahdut (The Unity), in Jerusalem. This marked the end of his career as a farm laborer. He contributed 15 articles to the periodical, eventually settling on "Ben-Gurion" as his pen name, chosen after the historic Joseph ben Gurion.

2.1. Activities in the Ottoman Empire and Constantinople

In spring 1911, with the Second Aliyah facing collapse, Poale Zion's leadership decided on a strategy of "Ottomanisation." Ben-Zvi, Manya Shochat, and Israel Shochat planned to study law in Istanbul, and Ben-Gurion was to join them. He first spent eight months in Thessaloniki learning Turkish, concealing his Ashkenazi identity due to local Sephardic prejudices. Ben-Zvi obtained a forged secondary school certificate for Ben-Gurion to join him at Dar al-Funun. Ben-Gurion was entirely dependent on funding from his father and struggled with ill health, spending some time in hospital. He and Ben-Zvi were later expelled from Palestine in 1915 by Jemal Pasha for their political activities.

2.2. Activities in the United States

Ben-Gurion was at sea, returning from Istanbul, when World War I broke out. He was not among the thousands of foreign nationals deported in December 1914. Based in Jerusalem, he and Ben-Zvi recruited forty Jews into a Jewish militia to assist the Ottoman Army. Despite his pro-Ottoman declarations, he was deported to Egypt in March 1915, from where he made his way to the United States, arriving in May.

For the next four months, Ben-Gurion and Ben-Zvi embarked on a speaking tour to visit Poale Zion groups in 35 cities, attempting to raise a pioneer army, Hechalutz, of 10,000 men to fight on the Ottoman side. The tour was largely a disappointment, with small audiences and limited recruitment. Ben-Gurion was hospitalized with diphtheria for two weeks and spoke on only five occasions, recruiting 19 volunteers, compared to Ben-Zvi's 44. A second tour in December saw him speak at 19 meetings. Due to limited awareness of Poale Zion's activities in Palestine, they decided to republish Yizkor in Yiddish. The Hebrew original, published in Jaffa in 1911, consisted of eulogies to Zionist martyrs and included Ben-Gurion's account of his Petah Tikva and Sejera experiences. The first Yiddish edition, published in February 1916, was an immediate success, selling all 3,500 copies. A second edition of 16,000 was published in August.

A follow-up, Eretz Israel - Past and Present, was conceived as an anthology of work from Poale Zion leaders, but Ben-Gurion took over as editor, writing the introduction and two-thirds of the text. He suspended all his Poale Zion activities, spending most of the next 18 months in the New York Public Library. Published in April 1918, it was 500 pages long and an immediate success, selling 7,000 copies in four months, with second and third editions printed. Total sales of 25,000 copies made a profit of 20.00 K USD for Poale Zion, making Ben-Gurion the most prominent Poale Zion leader in America.

In May 1918, Ben-Gurion joined the newly formed Jewish Legion of the British Army and trained at Fort Edward in Windsor, Nova Scotia. He volunteered for the 38th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, which fought against the Ottomans in the Palestine Campaign, though he remained in a Cairo hospital with dysentery. In 1918, after guarding prisoners of war in the Egyptian desert, his battalion was transferred to Sarafand. On 13 December 1918, he was demoted from corporal to private and fined three days' pay for being absent without leave to visit friends in Jaffa. He was demobilized in early 1919.

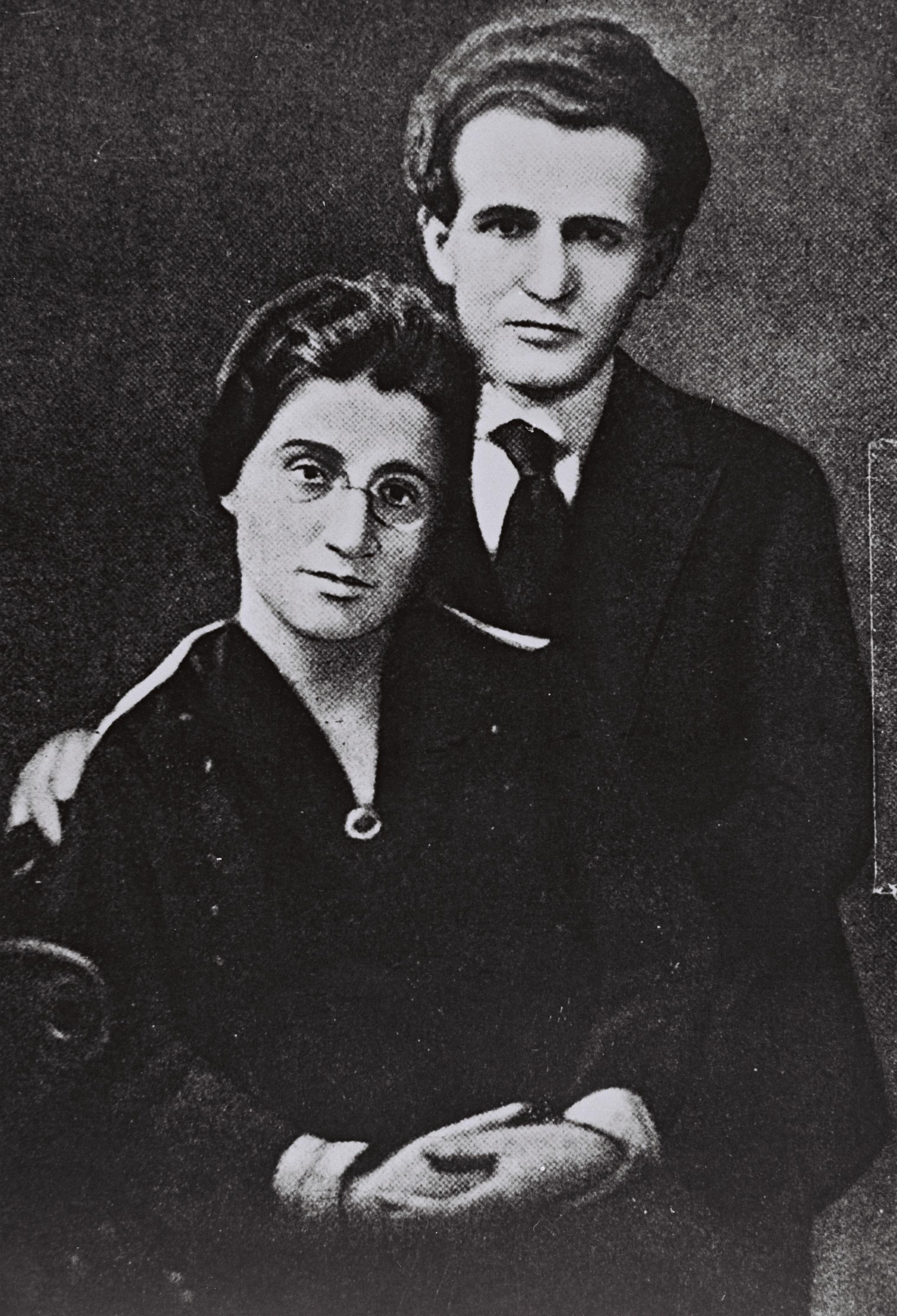

One of Ben-Gurion's companions when he made the Aliyah was Rachel Nelkin, whom he had met three years prior in Płońsk. Their expected relationship ended when he shut her out after her first day of laboring. While in New York City in 1915, he met Russian-born Paula Munweis, and they married in 1917. In November 1919, after an 18-month separation, Paula and their daughter Geula joined Ben-Gurion in Jaffa; it was the first time he met his one-year-old daughter. The couple had three children: a son, Amos, and two daughters, Geula Ben-Eliezer and Renana Leshem. Amos married Mary Callow, an Irish gentile who was pregnant with their first child. Although a Reform rabbi converted her to Judaism, neither the Palestine rabbinate nor Paula Ben-Gurion considered her a real Jew until she underwent an Orthodox conversion many years later. Amos became Deputy Inspector-General of the Israel Police and later director-general of a textile factory. He and Mary had six granddaughters from their two daughters and a son, Alon, who married a Greek gentile. Geula had two sons and a daughter, and Renana, a microbiologist at the Israel Institute for Biological Research, had a son.

3. Zionist Leadership and the Yishuv (Pre-State)

David Ben-Gurion's leadership was central to the development of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, during the British Mandate. His strategic vision and political acumen were instrumental in consolidating Zionist organizations and setting the stage for the establishment of the State of Israel.

3.1. Formation of Labor Zionist Parties

After the death of theorist Ber Borochov, the left-wing and centrist factions of Poalei Zion split in February 1919. Ben-Gurion and his friend Berl Katznelson led the centrist faction of the Labor Zionist movement, forming Ahdut HaAvoda with Ben-Gurion as its leader in March 1919. In 1930, Hapoel Hatzair (founded by A. D. Gordon in 1905) and Ahdut HaAvoda joined forces to create Mapai, a more moderate Zionist labor party. Mapai, although still a left-wing organization, was not as far-left as other factions, and it emerged under Ben-Gurion's leadership. In the 1940s, the left-wing of Mapai broke away to form Mapam. Labor Zionism became the dominant tendency in the World Zionist Organization, and in 1935, Ben-Gurion became chairman of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency, a role he maintained until the creation of the State of Israel in 1948.

3.2. Role in the Histadrut

In 1920, Ben-Gurion helped form the Histadrut, the General Federation of Laborers in the Land of Israel (the Zionist Labor Federation in Palestine), and served as its general secretary from 1921 until 1935. At Ahdut HaAvoda's 3rd Congress in 1924, veteran Poalei Zion leader Shlomo Kaplansky proposed supporting the British Mandatory authorities' plans for an elected legislative council in Palestine, arguing that a Parliament, even with an Arab majority, was the way forward. Ben-Gurion, already emerging as a leader of the Yishuv, successfully campaigned for the rejection of Kaplansky's ideas, demonstrating his early strategic stance on the future of Jewish self-governance. Ben-Gurion also played a role in the formation of self-defense organizations like the Haganah, which militarily countered attacks on kibbutzim by Arabs.

3.3. Leadership of the Jewish Agency

As head of the Jewish Agency from 1935, Ben-Gurion was the *de facto* leader of the Jewish community in Palestine, guiding the movement towards an independent Jewish state. In 1946, while staying at the same hotel in Paris, Ben-Gurion became friendly with North Vietnam's Politburo chairman Ho Chi Minh, who offered Ben-Gurion a Jewish home-in-exile in Vietnam. Ben-Gurion declined, stating his certainty that they would establish a Jewish Government in Palestine.

3.4. Policies during the British Mandate

During the 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Ben-Gurion instigated a policy of restraint (HavlagahHebrew) for the Haganah and other Jewish groups, dictating that they should not retaliate for Arab attacks against Jewish civilians, but focus solely on self-defense. In 1937, when the Peel Commission recommended partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab areas, Ben-Gurion supported this policy. This stance led to a conflict with Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who opposed partition, resulting in Jabotinsky's supporters splitting from the Haganah and abandoning Havlagah.

The British White Paper of 1939 stipulated that Jewish immigration to Palestine would be limited to 15,000 a year for the first five years, and subsequently contingent on Arab consent. Restrictions were also placed on the rights of Jews to buy land from Arabs. After this, Ben-Gurion changed his policy towards the British, stating: "Peace in Palestine is not the best situation for thwarting the policy of the White Paper." Believing that a peaceful solution with the Arabs was unlikely, he soon began preparing the Yishuv for war. According to historian Shabtai Teveth, through his campaign to mobilize the Yishuv in support of the British war effort, Ben-Gurion strove to build the nucleus of a "Hebrew Army," and his success in this endeavor later brought victory to Zionism in the struggle to establish a Jewish state.

During the Second World War, Ben-Gurion famously encouraged the Jewish population to volunteer for the British Army, telling Jews to "support the British as if there is no White Paper and oppose the White Paper as if there is no war." About 10% of the Jewish population of Palestine volunteered for the British Armed Forces, including many women. At the same time, Ben-Gurion assisted the illegal immigration of thousands of European Jewish refugees to Palestine during a period when the British placed heavy restrictions on Jewish immigration.

In 1944, the Irgun and Lehi, two Jewish right-wing armed groups, declared a rebellion against British rule and began attacking British administrative and police targets. Ben-Gurion and other mainstream Zionist leaders initially opposed armed action against the British. After Lehi assassinated Lord Moyne, the British Minister of State in the Middle East, Ben-Gurion decided to stop the insurgency by force. While Lehi was convinced to suspend operations, the Irgun refused. As a result, the Haganah initiated "The Saison" or "Hunting Season," supplying intelligence to the British to enable arrests of Irgun members, and abducting and often torturing Irgun members, handing some over to the British while detaining others in secret Haganah prisons. This campaign severely crippled the Irgun, which struggled to survive. Irgun leader Menachem Begin ordered his fighters not to retaliate to prevent a civil war. The Saison became increasingly controversial within the Yishuv, even within Haganah ranks, and was aborted by the end of March 1945.

At the end of World War II, the Zionist leadership expected a British decision to establish a Jewish state. However, it became clear that the British had no intention of immediately establishing a Jewish state and that limits on Jewish immigration would remain. Consequently, with Ben-Gurion's approval, the Haganah entered into a secret alliance with the Irgun and Lehi, forming the Jewish Resistance Movement in October 1945, and participated in attacks against the British. In June 1946, the British launched Operation Agatha, a large-scale police and military operation throughout Palestine to search for arms and arrest Jewish leaders and Haganah members. The British intended to detain Ben-Gurion during this operation, but he was visiting Paris at the time. The British stored captured documents from the Jewish Agency headquarters in the King David Hotel, which served as a military and administrative headquarters. Ben-Gurion agreed to the Irgun's plan to bomb the King David Hotel to destroy incriminating documents that he feared would prove Haganah's participation in the violent insurrection with Irgun and Lehi, with his and other Jewish Agency officials' approval. However, Ben-Gurion asked that the operation be delayed, but the Irgun refused. The King David Hotel bombing was carried out in July 1946, killing 91 people. Ben-Gurion publicly condemned the bombing, and subsequently ordered the dissolution of the Jewish Resistance Movement. From then on, while Irgun and Lehi continued their attacks, the Haganah rarely did so, and although Ben-Gurion and other mainstream Zionist leaders publicly condemned the attacks, in practice the Haganah rarely cooperated with the British in suppressing the insurgency.

Due to the Jewish insurgency, negative publicity over Jewish immigration restrictions, and Arab leaders' non-acceptance of a partitioned state, the British Government referred the matter to the United Nations. In September 1947, the British decided to terminate the Mandate. In November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution approving the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. While the Jewish Agency under Ben-Gurion accepted the plan, the Arabs rejected it, and the 1947-1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine broke out. Ben-Gurion's strategy was for the Haganah to hold every position without retreat or surrender, and then launch an offensive when British forces had evacuated sufficiently to preclude intervention. This strategy proved successful, and by May 1948, Jewish forces were winning the civil war.

4. Founding of Israel

David Ben-Gurion's leadership during the critical period leading to the establishment of the State of Israel was decisive, marked by the Declaration of Independence, his command during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and the profound, and often controversial, impact of his policies on the Palestinian population.

4.1. Declaration of Independence

On 14 May 1948, on the last day of the British Mandate, Ben-Gurion proclaimed the Israeli Declaration of Independence in Tel Aviv. In the declaration, he stated that the new nation would "uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race." A few hours later, the State of Israel officially came into being when the British Mandate terminated on 15 May, achieving UN membership on 11 May 1949.

4.2. Role in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War

Immediately after Israel's independence, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War began as numerous Arab nations invaded. During the first weeks of Israel's independence, Ben-Gurion oversaw the nascent state's military operations and ordered all militias to be replaced by one national army, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). He used a firm hand during the Altalena Affair in June 1948, involving a ship carrying arms purchased by the Irgun. Ben-Gurion insisted that all weapons be handed over to the IDF. When fighting broke out on the Tel Aviv beach, he ordered the ship to be taken by force and shelled. Sixteen Irgun fighters and three IDF soldiers were killed in this battle. Following the policy of a unified military force, he also ordered that the Palmach headquarters be disbanded and its units integrated with the rest of the IDF, to the chagrin of many of its members. His attempts to reduce the number of Mapam members in the senior ranks led to "The Generals' Revolt" in June 1948.

In his War Diaries in February 1948, Ben-Gurion wrote: "The war shall give us the land. The concepts of 'ours' and 'not ours' are peace concepts only, and they lose their meaning during war." He later confirmed this by stating, "In the Negev we shall not buy the land. We shall conquer it. You forget that we are at war." After the ten-day campaign during the 1948 war, the Israelis were militarily superior to their enemies. On 26 September, Ben-Gurion argued to the Cabinet for attacking Latrun again and conquering the whole or a large part of the West Bank. The motion was rejected by a vote of seven to five after discussions. Ben-Gurion qualified the cabinet's decision as bechiya ledorotHebrew ("a source of lament for generations"), considering Israel may have lost forever the Old City of Jerusalem. There is controversy around these events; some historians, like Uri Bar-Joseph, contend Ben-Gurion sought only a limited action on Latrun, not an all-out offensive, a view supported by David Tal who found no substantiation in Ben-Gurion's diary or Cabinet protocols for a full West Bank conquest plan.

The topic resurfaced at the end of the 1948 war, when General Yigal Allon also proposed conquering the West Bank up to the Jordan River as a natural, defensible border. This time, Ben-Gurion refused, despite knowing the IDF's military strength. He feared the reaction of Western powers and wished to maintain good relations with the United States and avoid provoking the British. Furthermore, he believed the war's results were satisfactory and that Israeli leaders should focus on nation-building.

4.2.1. Plan Dalet

Plan Dalet was a plan worked out by the Haganah in Mandatory Palestine in March 1948, requested by Ben-Gurion, consisting of a set of guidelines to take control of Mandatory Palestine, declare a Jewish state, and defend its borders and people, including the Jewish population outside of the borders, "before, and in anticipation of" the invasion by regular Arab armies. According to the Israeli Yehoshafat Harkabi, Plan Dalet called for the conquest of Arab towns and villages inside and along the borders of the area allocated to the proposed Jewish State in the UN Partition Plan. In case of resistance, the population of conquered villages was to be expelled outside the borders of the Jewish state. If no resistance was met, the residents could stay put, under military rule. The intent of Plan Dalet has been long debated by historians, with some asserting it was entirely defensive, while others contend it was a deliberate plan for expulsion or ethnic cleansing.

4.3. Palestinian Exodus

The 1948 Arab-Israeli War led to the mass expulsion and flight of the majority of the Palestinian Arab population. Israeli historian Benny Morris wrote that the idea of expulsion of Palestinian Arabs was endorsed in practice by mainstream Zionist leaders, particularly Ben-Gurion. Morris claims that Ben-Gurion did not give clear or written orders in that regard, but his subordinates understood his policy well: "From April 1948, Ben-Gurion is projecting a message of transfer. There is no explicit order of his in writing, there is no orderly comprehensive policy, but there is an atmosphere of [population] transfer. The transfer idea is in the air. The entire leadership understands that this is the idea. The officer corps understands what is required of them. Under Ben-Gurion, a consensus of transfer is created." Morris further asserts that if Ben-Gurion "had carried out a large expulsion and cleansed the whole country - the whole Land of Israel, as far as the Jordan River. It may yet turn out that this was his fatal mistake. If he had carried out a full expulsion rather than a partial one - he would have stabilized the State of Israel for generations."

In his War Diaries in February 1948, Ben-Gurion noted to the Mapai Council: "From your entry to Jerusalem, through Lifta, Romema [East Jerusalem]... there are no Arabs. One hundred percent Jews. Since Jerusalem was destroyed by Rome, Judaism has not been like it is now. In Arab neighborhoods, many in the west see none of the Arabs I do. Do not assume that this will change... What happened in Jerusalem... may happen in many parts of the country... in six, eight, or ten months of campaigning there will certainly be great changes in the population composition of the country." Morris has also stated that Ben-Gurion "covered up for the officers who did the massacres," citing cases like Saliha, Deir Yassin, Lod, Dawayima, Jaffa, and Arab al Muwassi. He suggests that in Operation Hiram (October 1948), there was an unusually high concentration of executions carried out "in an orderly fashion," implying a pattern.

David Ben-Gurion also oversaw and approved Israel's biological warfare poisoning operations, known as Operation Cast Thy Bread, against Palestinian Arab civilians during the 1948 war. These operations involved targeting dozens of Palestinian water wells with typhoid and dysentery bacteria, as well as aqueducts in Palestinian cities such as Acre, leading to typhoid epidemics and mass infections.

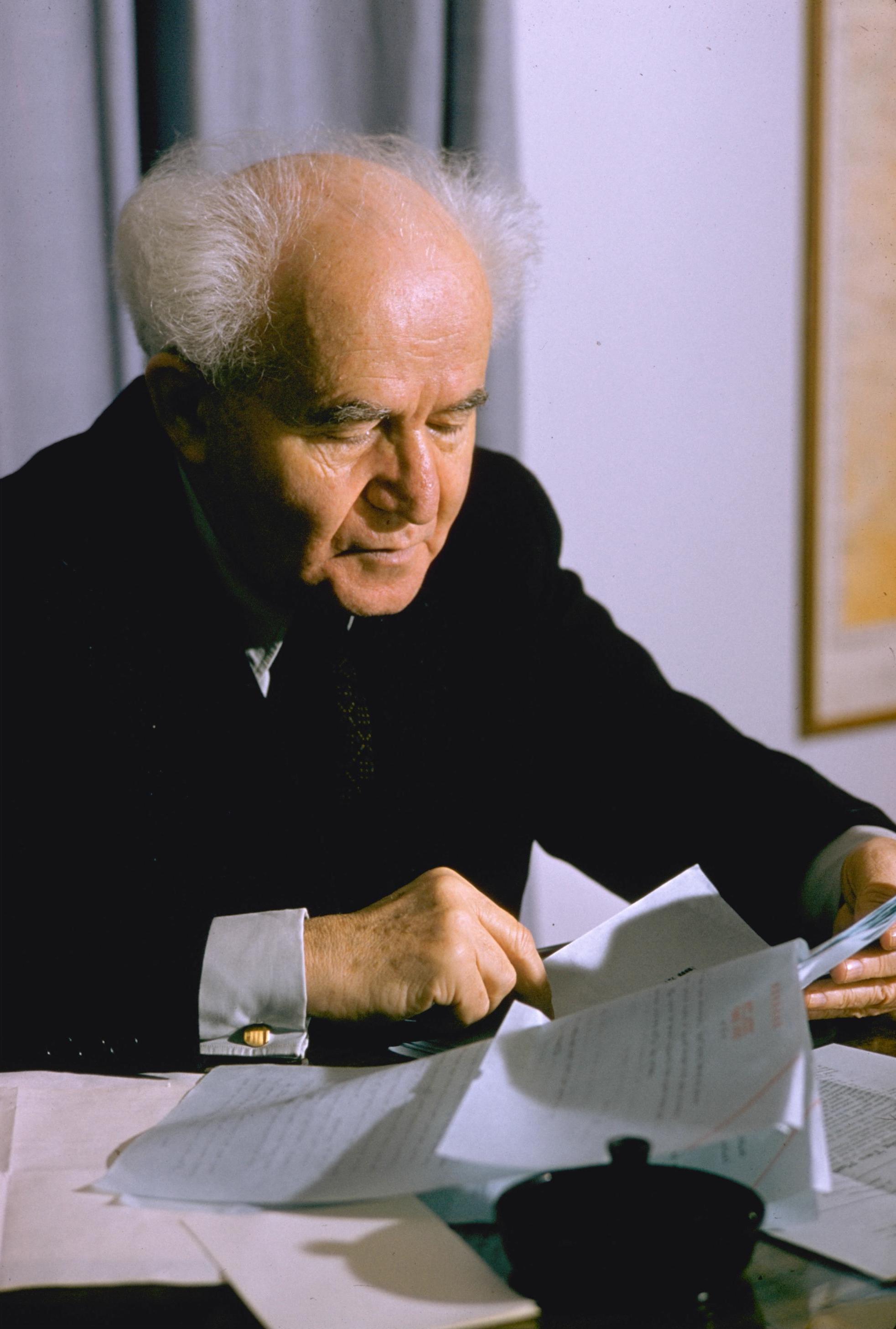

5. Prime Ministership

David Ben-Gurion's two terms as Prime Minister were characterized by intensive state-building efforts, ambitious national development projects, and a series of decisive, often controversial, military and foreign policy decisions that shaped the nascent State of Israel.

5.1. First Tenure as Prime Minister (1948-1954)

After leading Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Ben-Gurion was elected Prime Minister of Israel when his Mapai (Labor) party won the largest number of Knesset seats in the first national election, held on 14 February 1949. He remained in that post until 1963, except for a period of nearly two years between 1954 and 1955. As prime minister, he oversaw the establishment of the state's institutions and presided over various national projects aimed at the rapid development of the country and its population. These included Operation Magic Carpet, the airlift of approximately 45,000 Jews from Yemen and other Arab countries, the construction of the National Water Carrier of Israel, rural development projects, and the establishment of new towns and cities. He particularly called for pioneering settlement in outlying areas, especially in the Negev desert. Ben-Gurion believed that the sparsely populated and barren Negev offered a great opportunity for Jews to settle in Palestine with minimal obstruction of the Arab population and set a personal example by settling in kibbutz Sde Boker at the center of the Negev. He saw the struggle to make the Negev desert bloom as an area where the Jewish people could make a major contribution to humanity.

During this period, Palestinian fedayeen repeatedly infiltrated Israel from Arab territory. In 1953, after unsuccessful retaliatory actions, Ben-Gurion charged Ariel Sharon, then security chief of the northern region, with setting up a new commando unit designed to respond to fedayeen infiltrations. Ben-Gurion told Sharon, "The Palestinians must learn that they will pay a high price for Israeli lives." Sharon formed Unit 101, a small commando unit answerable directly to the IDF General Staff, tasked with retaliating for fedayeen raids. During its five months of existence, the unit launched repeated raids against military targets and villages used as fedayeen bases. These attacks became known as the reprisal operations.

One such operation, the Qibya massacre in October 1953, gained international condemnation of Israel after an Israeli army attack on the village of Qibya in the then Jordanian-ruled West Bank resulted in the massacre of 69 Palestinian villagers, two-thirds of them women and children. Ben-Gurion denied the army's involvement, falsely claiming the attack was carried out by Israeli civilians, and was seen as having protected involved subordinates in the military from accountability.

In 1953, Ben-Gurion announced his intention to withdraw from government and was replaced by Moshe Sharett, who was elected the second Prime Minister of Israel in January 1954. However, Ben-Gurion temporarily served as acting prime minister when Sharett visited the United States in 1955. During Ben-Gurion's tenure as acting prime minister, the IDF carried out Operation Olive Leaves, a successful attack on fortified Syrian emplacements near the northeastern shores of the Sea of Galilee, in response to Syrian attacks on Israeli fishermen. Ben-Gurion had ordered the operation without consulting the Israeli cabinet, and Sharett would later bitterly complain that Ben-Gurion had exceeded his authority.

5.2. Second Tenure as Prime Minister (1955-1963)

Ben-Gurion returned to government in 1955, assuming the post of defense minister and soon being re-elected prime minister. Upon his return, Israeli forces began responding more aggressively to Egyptian-sponsored Palestinian guerrilla attacks from Gaza. Egypt's President Gamal Abdel Nasser signed the Egyptian-Czech arms deal and purchased a large number of modern arms, while Israel responded by arming itself with help from France. Nasser blocked the passage of Israeli ships through the Straits of Tiran and the Suez Canal. In July 1956, the United States and Britain withdrew their offer to fund the Aswan High Dam project on the Nile, and a week later, Nasser nationalized the French and British-controlled Suez Canal.

In late 1956, the bellicosity of Arab statements prompted Israel to remove the threat of concentrated Egyptian forces in the Sinai. Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula during what became known as the Suez Crisis (also Sinai War). Other Israeli aims were the elimination of fedayeen incursions into Israel that made life unbearable for its southern population and opening the blockaded Straits of Tiran for Israeli ships. Israel occupied much of the peninsula within a few days. As agreed beforehand, within a couple of days, Britain and France also invaded, aiming to regain Western control of the Suez Canal and remove Nasser. However, pressure from the United States forced the British and French to back down and Israel to withdraw from Sinai in return for free Israeli navigation through the Red Sea. The United Nations responded by establishing its first peacekeeping force, the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF), stationed between Egypt and Israel, which maintained peace and stopped fedayeen incursions for the next decade.

In 1957, Ben-Gurion was injured by a grenade thrown into the Knesset plenum by a troubled Jewish immigrant from Syria, Moshe Dwek, who claimed that nobody was attentive to his needs. In 1959, Ben-Gurion learned from West German officials that the notorious Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, was likely living in hiding in Argentina. In response, Ben-Gurion ordered the Israeli foreign intelligence service, the Mossad, to capture Eichmann alive for trial in Israel. In 1960, the mission was accomplished, and Eichmann was tried and convicted in an internationally publicized Eichmann trial for various offenses, including crimes against humanity, and was subsequently executed in 1962.

Ben-Gurion was "nearly obsessed" with Israel's obtaining nuclear weapons, feeling that a nuclear arsenal was the only way to counter the Arabs' superiority in numbers, space, and financial resources, and that it was the only sure guarantee of Israel's survival and the prevention of another Holocaust. During his final months as premier, Ben-Gurion was engaged in a, now declassified, diplomatic standoff with the United States over the issue.

Ben-Gurion stepped down as prime minister on 16 June 1963. According to historian Yechiam Weitz, when he unexpectedly resigned, he was asked to reconsider by the cabinet, but no serious efforts were made to dissuade him, unlike his resignation in 1953. Weitz attributes his reasons to "his political isolation, suspicion of colleagues and rivals, apparent inability to interact with the full spectrum of reality, and belief that his life's work was disintegrating. His resignation was not an act of farewell but another act of his personal struggle and possibly an indication of his mental state." Ben-Gurion chose Levi Eshkol as his successor. A year later, a bitter rivalry developed between the two over the Lavon Affair, a failed 1954 Israeli covert operation in Egypt. Ben-Gurion insisted that the operation be properly investigated, while Eshkol refused. After failing to unseat Eshkol as Mapai party leader in the 1965 Mapai leadership election, Ben-Gurion subsequently broke with Mapai in June 1965 and formed a new party, Rafi, while Mapai merged with Ahdut HaAvoda to form Alignment, with Eshkol at its head. Alignment defeated Rafi in the November 1965 election, establishing Eshkol as the country's leader.

6. Later Political Career

After his second tenure as Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion remained a significant, albeit often critical, voice in Israeli politics. His later years were marked by reflections on the state's future, particularly concerning its borders and demography.

In May 1967, Egypt began massing forces in the Sinai Peninsula after expelling UN peacekeepers and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. This, together with the actions of other Arab states, caused Israel to begin preparing for war, a situation that lasted until the outbreak of the Six-Day War on 5 June. In Jerusalem, there were calls for a national unity government or an emergency government. During this period, Ben-Gurion met with his old rival Menachem Begin in Sde Boker, and Begin asked Ben-Gurion to join Eshkol's national unity government. Although Eshkol's Mapai party initially opposed the widening of its government, it eventually changed its mind. On 23 May, IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin met with Ben-Gurion to ask for reassurance. However, Ben-Gurion accused Rabin of putting Israel in mortal danger by mobilizing the reserves and openly preparing for war with an Arab coalition, stating that he should have obtained the support of a foreign power, as he had done during the Suez Crisis. Rabin was reportedly shaken by the meeting and took to bed for 36 hours.

After the Israeli government decided to go to war, planning a preemptive strike to destroy the Egyptian Air Force followed by a ground offensive, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan informed Ben-Gurion of the impending attack on the night of 4-5 June. Ben-Gurion subsequently wrote in his diary that he was troubled by Israel's impending offensive. On 5 June, the Six-Day War began with Operation Focus, an Israeli air attack that decimated the Egyptian air force. Israel then captured the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria in a series of campaigns. Following the war, Ben-Gurion was in favor of returning all the captured territories apart from East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, and Mount Hebron as part of a peace agreement.

On 11 June, Ben-Gurion met with a small group of supporters in his home. During the meeting, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan proposed autonomy for the West Bank, the transfer of Gazan refugees to Jordan, and a united Jerusalem serving as Israel's capital. Ben-Gurion agreed with him but foresaw problems in transferring Palestinian refugees from Gaza to Jordan, and recommended that Israel insist on direct talks with Egypt, favoring withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for peace and free navigation through the Straits of Tiran. The following day, he met with Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek in his Knesset office. Despite Kollek occupying a lower executive position, Ben-Gurion treated him like a subordinate.

Following the Six-Day War, Ben-Gurion criticized what he saw as the government's apathy towards the construction and development of Jerusalem. To ensure that a united Jerusalem remained in Israeli hands, he advocated a massive Jewish settlement program for the Old City and the hills surrounding the city, as well as the establishment of large industries in the Jerusalem area to attract Jewish migrants. He argued that no Arabs would have to be evicted in the process. Ben-Gurion also urged extensive Jewish settlement in Hebron.

In 1968, when Rafi merged with Mapai to form the Alignment, Ben-Gurion refused to reconcile with his old party. He favored electoral reforms in which a constituency-based system would replace what he saw as a chaotic proportional representation method. He formed another new party, the National List, which won four seats in the 1969 election.

7. Views, Ideology, and Philosophy

David Ben-Gurion's ideology was a complex blend of Zionism, socialism, and pragmatism, shaped by his early exposure to various political movements. His views on Arab relations, religion, and the state's future were often nuanced and, at times, contradictory.

Ben-Gurion deeply admired Lenin and intended to be a "Zionist Lenin." According to his biographer Tom Segev, Ben-Gurion admired Lenin's decisive nature, his ability to "disdain all obstacles, faithful to his goal, who knows no concessions or discounts, the extreme of extremes." Shimon Peres recalled Ben-Gurion preferring Lenin to Trotsky, not for intellect, but for decisiveness. Peres noted that Lenin would "cut the Gordian knot, accepting losses while focusing on the essentials," unlike Trotsky, who "manoeuvred." In Peres' opinion, the essence of Ben-Gurion's life work was "the decisions he made at critical junctures in Israel's history," especially his acceptance of the 1947 partition plan, a painful compromise that enabled Israel's establishment.

Ben-Gurion consistently viewed television as a medium that promoted ignorance, rejecting proposals by figures like Yigael Yadin to use it for national unity and education. Consequently, television only began to spread in Israel around the mid-1960s, after he had left the premiership.

7.1. Views on Arab Relations and Coexistence

Ben-Gurion published two volumes setting out his views on relations between Zionists and the Arab world: We and Our Neighbors, published in 1931, and My Talks with Arab Leaders, published in 1967. Ben-Gurion believed in the equal rights of Arabs who remained in and would become citizens of Israel. He was quoted as saying, "We must start working in Jaffa. Jaffa must employ Arab workers. And there is a question of their wages. I believe that they should receive the same wage as a Jewish worker. An Arab has also the right to be elected president of the state, should he be elected by all."

Ben-Gurion recognized the strong attachment of Palestinian Arabs to the land, but hoped this would diminish over time. In an address to the United Nations on 2 October 1947, he doubted the likelihood of peace: "This is our native land; it is not as birds of passage that we return to it. But it is situated in an area engulfed by Arabic-speaking people, mainly followers of Islam. Now, if ever, we must do more than make peace with them; we must achieve collaboration and alliance on equal terms. Remember what Arab delegations from Palestine and its neighbors say in the General Assembly and in other places: talk of Arab-Jewish amity sound fantastic, for the Arabs do not wish it, they will not sit at the same table with us, they want to treat us as they do the Jews of Bagdad, Cairo, and Damascus."

Nahum Goldmann, president of the World Jewish Congress, criticized Ben-Gurion for what he viewed as a confrontational approach to the Arab world. Goldmann wrote, "Ben-Gurion is the man principally responsible for the anti-Arab policy, because it was he who molded the thinking of generations of Israelis." Goldmann reported that Ben-Gurion had told him in private in 1956: "Why should the Arabs make peace? If I was an Arab leader I would never make terms with Israel. That is natural: we have taken their country. Sure, God promised it to us, but what does that matter to them? Our God is not theirs. We come from Israel, it's true, but two thousand years ago, and what is that to them? There has been anti-Semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz, but was that their fault? They only see one thing: we have come here and stolen their country. Why should they accept that? They may, perhaps, forget in time, in one or two generations, but for the time being there is no chance. So it is simple. We have to keep strong and maintain a powerful army."

Simha Flapan quoted Ben-Gurion as stating in 1938: "I believe in our power, in our power which will grow, and if it will grow agreement will come..." Ben-Gurion attempted to learn Arabic in 1909 but gave up. He later became fluent in Turkish, and used English, and to a lesser extent French, in discussions with Arab leaders.

7.2. Religious Beliefs and Status Quo

Ben-Gurion described himself as an irreligious person who developed atheism in his youth and demonstrated no great sympathy for the elements of traditional Judaism, though he quoted the Bible extensively. Modern Orthodox philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz considered Ben-Gurion "to have hated Judaism more than any other man he had met." Ben-Gurion was proud of having set foot in a synagogue only once in Israel, when independence was declared, at the request of Rabbi Bar-Ilan of the Mizrachi Party. He also worked on Yom Kippur and ate pork.

In later life, Ben-Gurion refused to define himself as "secular," regarding himself as a believer in God. In a 1970 interview, he described himself as a pantheist and stated, "I don't know if there's an afterlife. I think there is." In 1969, he combined his Zionism with a moderate religious view: "In 1948 the establishment of a Hebrew state and the independence of Israel were declared, because our people were sure that their prayer would be answered if they would return to the land." Two years before his death, in an interview with the leftist weekly Hotam, he revealed, "I too have a deep faith in the Almighty. I believe in one God, the omnipotent Creator. My consciousness is aware of the existence of material and spirit... [But] I cannot understand how order reigns in nature, in the world and universe-unless there exists a superior force. This supreme Creator is beyond my comprehension... but it directs everything."

In a letter to the writer Eliezer Steinman, he wrote, "Today, more than ever, the 'religious' tend to relegate Judaism to observing dietary laws and preserving the Sabbath. This is considered religious reform. I prefer the Fifteenth Psalm, lovely are the psalms of Israel. The Shulchan Aruch is a product of our nation's life in the Exile. It was produced in the Exile, in conditions of Exile. A nation in the process of fulfilling its every task, physically and spiritually... must compose a 'New Shulchan'-and our nation's intellectuals are required, in my opinion, to fulfill their responsibility in this."

To prevent the coalescence of the religious right, the Histadrut agreed to a vague status quo agreement with Mizrahi in 1935. In September 1947, Ben-Gurion decided to reach a formal status quo agreement with the Orthodox Agudat Yisrael party. He sent a letter to Agudat Yisrael stating that while being committed to establishing a non-theocratic state with freedom of religion, he promised that the Shabbat would be Israel's official day of rest, that in state-provided kitchens there would be access to kosher food, that every effort would be made to provide a single jurisdiction for Jewish family affairs, and that each sector would be granted autonomy in education, provided minimum curriculum standards were observed. This agreement largely provided the framework for religious affairs in Israel to the present day.

8. Personal Life

David Ben-Gurion's personal life, particularly his marriage and his decision to settle in the Negev, reflected his deep commitment to the Zionist project and his vision for Israel's future.

One of Ben-Gurion's companions when he made the Aliyah in 1906 was Rachel Nelkin, whom he had met three years previously in Płońsk. While it was expected their relationship would continue, he distanced himself from her after she was fired from her first day of laboring. While in New York City in 1915, he met Russian-born Paula Munweis, and they married in 1917. In November 1919, after an 18-month separation, Paula and their daughter Geula joined Ben-Gurion in Jaffa; it was the first time he met his one-year-old daughter. The couple had three children: a son, Amos, and two daughters, Geula Ben-Eliezer and Renana Leshem.

Amos married Mary Callow, an Irish gentile who was already pregnant with their first child. Although a Reform rabbi converted her to Judaism soon after, neither the Palestine rabbinate nor her mother-in-law, Paula Ben-Gurion, considered her a real Jew until she underwent an Orthodox conversion many years later. Amos became Deputy Inspector-General of the Israel Police and also the director-general of a textile factory. He and Mary had six granddaughters from their two daughters and a son, Alon, who married a Greek gentile. Geula had two sons and a daughter, and Renana, who worked as a microbiologist at the Israel Institute for Biological Research, had a son.

Ben-Gurion retired from politics in 1970 and spent his last years living in a modest home in Kibbutz Sde Boker, working on an 11-volume history of Israel's early years. Ben-Gurion believed that the sparsely populated and barren Negev desert offered a great opportunity for Jews to settle in Palestine with minimal obstruction of the Arab population, and he set a personal example by choosing to settle in Kibbutz Sde Boker in the center of the Negev. He also established the National Water Carrier of Israel to bring water to the area. He saw the struggle to make the desert bloom as a realm where the Jewish people could make a major contribution to humanity as a whole.

9. Controversies and Criticisms

David Ben-Gurion's career, while celebrated for establishing Israel, was also marked by significant controversies and criticisms, particularly concerning his prioritization of Zionist goals, conflicts with political rivals, and his role in the displacement of Palestinians.

Ben-Gurion was among the Zionist leaders who prioritized Zionist goals over rescuing Jews during the Holocaust. A prominent quote from him in 1938 summarizes this view: "If I knew that it would be possible to save all the children in Germany by transporting them to England, and only half of them by transporting them to Eretz Israel, I would choose the second - because we are not only accounting for these children, but also for the history of the Jewish people." While at the time he likely could not have imagined the full extent of the imminent tragedy, this ideology remained a cornerstone of mainstream Zionist thought throughout the Holocaust.

Ben-Gurion had great animosity toward Revisionist Zionist founder Ze'ev Jabotinsky, once reportedly calling him "Vladimir Hitler." When Jabotinsky died in 1940, his will stipulated that his remains be "transferred to the Land of Israel only at the express order of the Jewish government of that country." Ben-Gurion, then Prime Minister, consistently refused to allow Jabotinsky's reburial in Israel during his premiership, arguing that "Our country does not need dead people, only living ones." This policy persisted for over a decade until his retirement in 1963. Much later, Prime Minister Levi Eshkol gave permission for reburial in Jerusalem's Mount Herzl in 1964.

Conflicts with political rivals were frequent throughout his career. Beyond his rivalry with Jabotinsky, his relationship with Menachem Begin and the Irgun was fraught with tension, particularly during the King David Hotel bombing and the Altalena Affair. Later, after his first retirement, he developed a bitter rivalry with his chosen successor, Levi Eshkol, over the handling of the Lavon Affair, which ultimately led him to break away from Mapai and form a new party, Rafi.

10. Legacy and Commemoration

David Ben-Gurion's legacy is profoundly etched into the fabric of Israel, commemorating him as the nation's primary founder and a transformative leader whose vision and determination shaped its early decades.

10.1. Awards and Honors

Ben-Gurion received numerous awards and honors for his contributions to Zionism and the State of Israel:

- In 1949, he was awarded the Solomon Bublick Award of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in recognition of his contributions to the State of Israel.

- In both 1951 and 1971, he was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.

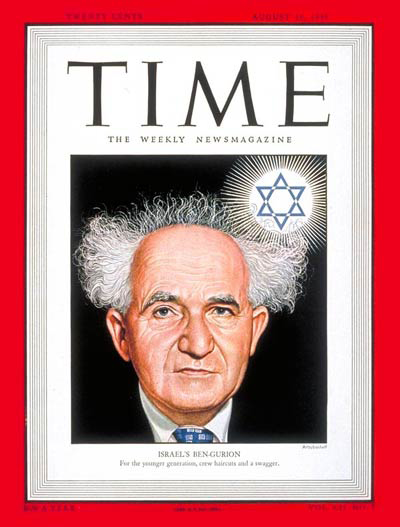

- Posthumously, Ben-Gurion was named one of Time magazine's "100 Most Important People of the 20th century."

10.2. Commemoration

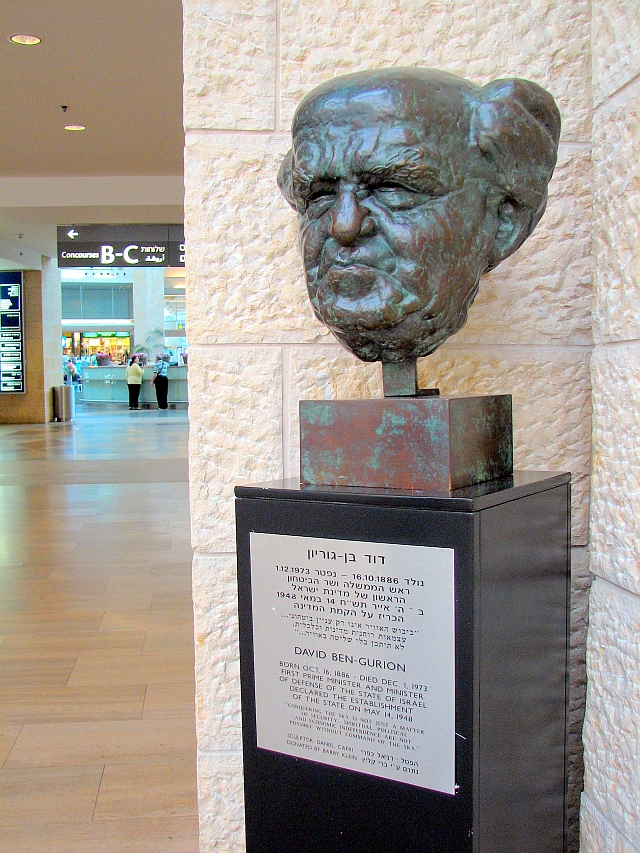

Ben-Gurion is widely commemorated in Israel and internationally, reflecting his enduring impact:

- Israel's largest airport, Ben Gurion International Airport, is named in his honor.

- One of Israel's major universities, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, located in Beersheba, is named after him.

- Numerous streets and schools throughout Israel have been named after him.

- An Israeli modification of the British Centurion Tank was named "Ben-Gurion" by Western media.

- Ben-Gurion's Hut in Kibbutz Sde Boker, where he lived his final years, is now a visitors' center, featuring a "Feet on the ground" statue of him by Rafael Maimon, depicting a yoga posture that Ben-Gurion, a yoga enthusiast, would often perform.

- A desert research center, Midreshet Ben-Gurion, near his "hut" in Kibbutz Sde Boker, has been named in his honor. Ben-Gurion's grave, where he is buried alongside his wife Paula, is located in the research center.

- An English Heritage blue plaque, unveiled in 1986, marks where Ben-Gurion lived in London at 75 Warrington Crescent, Maida Vale.

- In the 7th arrondissement of Paris, part of a riverside promenade of the Seine is named Esplanade Ben Gourion.

- His portrait appears on both the 500 lirot and the 50 (old) sheqalim banknotes issued by the Bank of Israel.

- His birthplace in Płońsk, Poland, is commemorated by the David Ben-Gurion Square, and the house where he grew up is also a notable site.

- In 1974, Israel issued memorial stamps featuring his likeness.

- He is often regarded as the "founding father" of Israel, akin to George Washington for the United States or Mahatma Gandhi for India.

- Ben-Gurion famously stated, "In Israel, in order to be a realist, you must believe in miracles."

- Regarding relations with Japan, Ben-Gurion stated on 1 July 1952, "Israel and Japan are located at opposite ends of Asia, but this fact does not separate them; rather, it connects them. The vast Asian continent is a connecting path between the two countries, and an awareness of Asia's destiny is a shared sentiment for both countries."