1. Life

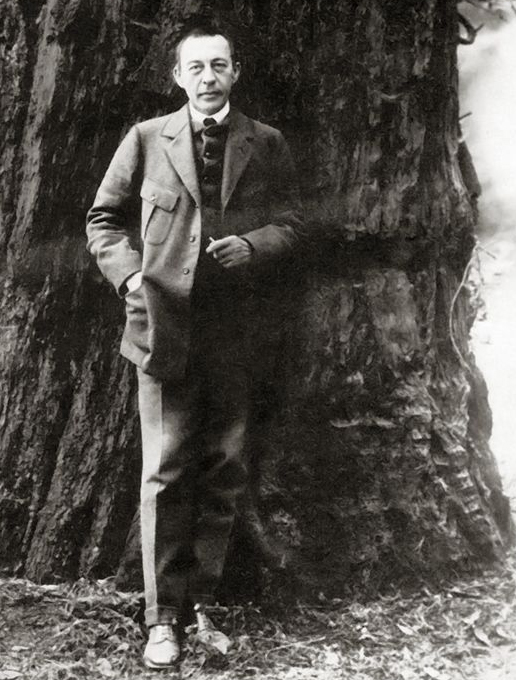

Sergei Rachmaninoff's life was marked by periods of intense creative output, personal setbacks, and significant geopolitical upheaval that ultimately led to his permanent departure from his homeland.

1.1. Birth and Early Years

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninoff was born on April 1, 1873, into a family of the Russian aristocracy in the village of Semyonovo, near Staraya Russa, Novgorod Governorate, in the Russian Empire. Family tradition claims his descent from a legendary Vasily, nicknamed "Rachman," supposedly a grandson of Stephen III of Moldavia. The Rachmaninoff family had strong musical and military inclinations. His paternal grandfather, Arkady Alexandrovich Rachmaninoff, was an amateur musician who had taken lessons from the Irish composer John Field. His father, Vasily Arkadievich Rachmaninoff (1841-1916), was a retired army officer and amateur pianist. He married Lyubov Petrovna Butakova (1853-1929), the daughter of a wealthy army general who provided five estates as part of her dowry. The couple had three sons-Vladimir, Sergei, and Arkady-and three daughters-Yelena, Sofia, and Barbara; Sergei was their third child. While his father possessed musical talent, he lacked the financial acumen to maintain the inherited estates, leading to the family's gradual decline.

After Sergei turned four, the family relocated to another property, the Oneg estate, about 112 mile (180 km) north of Semyonovo. Sergei spent his childhood there until the age of nine, and he mistakenly cited Oneg as his birthplace in later life. The Semyonovo estate was sold in 1879. Sergei began piano and music lessons at age four, organized by his mother, who noticed his remarkable ability to reproduce musical passages from memory without error. Upon hearing of his gift, his grandfather Arkady suggested hiring Anna Ornatskaya, a piano teacher and recent graduate of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, to live with the family and provide formal piano instruction. Rachmaninoff later dedicated his famous romance for voice and piano, "Spring Waters" from his Op. 14, to Ornatskaya.

His father, Vasily, initially wished for Sergei to be trained by the Page Corps and join the military. However, due to his financial incompetence and mounting debts, he had to sell the family's five estates one by one, making an expensive military career for Sergei unaffordable. His older brother Vladimir was sent to an ordinary military college. The last estate in Oneg was auctioned off in 1882, and the family moved to a small flat in Saint Petersburg. In 1883, Ornatskaya arranged for the then 10-year-old Rachmaninoff to study music at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory under her former teacher, Gustav Kross. Later that year, his sister Sofia died at the age of 13 from diphtheria, and his father left the family for Moscow. His maternal grandmother, Sofia Litvikova Butakova, a widow of General Butakov, stepped in to help raise the children and manage household expenses. She particularly focused on their religious life, regularly taking Rachmaninoff to Russian Orthodox Church services, where he first encountered liturgical chants and church bells, elements that would later permeate his compositions.

In 1885, Rachmaninoff suffered another significant loss when his sister Yelena died at age 18 from pernicious anaemia. Yelena had been an important musical influence, introducing him to the works of Tchaikovsky. As a respite from this tragedy, his grandmother took him to a farm retreat by the Volkhov River, where he developed a love for rowing. At the Conservatory, however, he adopted a relaxed attitude, played truant, failed his general education classes, and purposely altered his report cards. Despite performing at events attended by figures like Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich of Russia, Ornatskaya informed his mother that his admission to further education might be revoked due to his failing spring exams. His mother then consulted with her nephew, Alexander Siloti, an accomplished pianist and student of Franz Liszt. Siloti recommended transferring Rachmaninoff to the Moscow Conservatory to study with his own former teacher, the more strict Nikolai Zverev, a move that took place in 1885 and lasted until 1888.

1.2. Education

In the autumn of 1885, Rachmaninoff moved into Zverev's home, a common practice at the time, and resided there for nearly four years. During this period, he befriended fellow pupil Alexander Scriabin. While living at Zverev's, Rachmaninoff shared a bedroom with three other students, taking turns practicing the piano for three hours daily. Zverev instilled strict discipline in Rachmaninoff, laying the foundation for his piano technique. Many prominent musicians visited Zverev's home, and Rachmaninoff's talent was recognized and nurtured by Tchaikovsky.

After two years of tuition, the fifteen-year-old Rachmaninoff was awarded a Rubinstein scholarship. He graduated from the lower division of the Conservatory to become a pupil of Siloti in advanced piano, Sergei Taneyev in counterpoint, and Anton Arensky in free composition. He also attended Stepan Smolensky's lectures on Orthodox chants, which provided a foundation for his later sacred compositions.

In 1889, a rift formed between Rachmaninoff and Zverev, then his adviser, after Zverev rejected the composer's request for assistance in renting a piano and securing more privacy for composition. Zverev, who believed composition was a waste for talented pianists, refused to speak to Rachmaninoff for some time and arranged for him to live with his uncle and aunt, the Satins, in Moscow. It was during this time that Rachmaninoff experienced his first romance with Vera, the youngest daughter of the neighboring Skalon family. Although her mother objected and forbade direct correspondence, he continued to write to Vera by enclosing letters to her within letters to her older sister, Natalia. These letters provide valuable insights into Rachmaninoff's earliest compositions.

In 1890, Rachmaninoff spent his summer break with the Satins at Ivanovka, their private country estate near Tambov. The peaceful, bucolic surroundings became a significant source of inspiration for the composer, who returned there many times until 1917. Many compositions were completed at Ivanovka, including his Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 1, which he finished in July 1891 and dedicated to Siloti. That same year, Rachmaninoff completed the one-movement Youth Symphony and the symphonic poem Prince Rostislav.

When Siloti left the Moscow Conservatory after the 1891 academic year, Rachmaninoff requested to take his final piano exams a year early to avoid being assigned a different teacher. Despite Siloti's and Conservatory director Vasily Safonov's low expectations due to only three weeks of preparation, Rachmaninoff received assistance from a recent graduate familiar with the tests and passed each with honors in July 1891. Three days later, he passed his annual theory and composition exams. His progress was unexpectedly halted in the latter half of 1891 when he contracted a severe case of malaria during his summer break at Ivanovka.

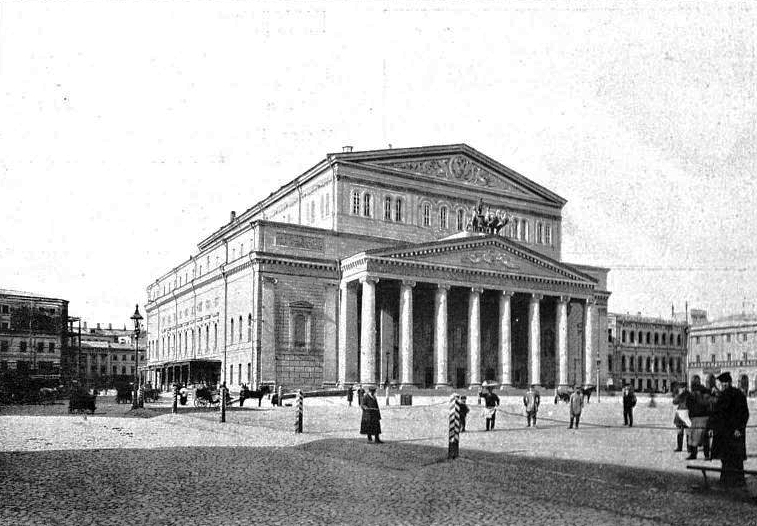

During his final year at the Conservatory, Rachmaninoff performed his first independent concert, premiering his Trio élégiaque No. 1 in January 1892, followed by a performance of the first movement of his Piano Concerto No. 1 two months later. His request to take his final theory and composition exams a year early was also granted, for which he wrote Aleko, a one-act opera based on Alexander Pushkin's narrative poem The Gypsies, in just seventeen days. It premiered in May 1892 at the Bolshoi Theatre; Tchaikovsky attended and praised Rachmaninoff for his work. Rachmaninoff, expecting it to "surely fail," was surprised by its success, leading the theatre to agree to further productions starring singer Feodor Chaliapin, who became a lifelong friend. Aleko earned Rachmaninoff the highest mark at the Conservatory and a Great Gold Medal, a distinction previously awarded only to Taneyev and Arseny Koreshchenko. Zverev, a member of the exam committee, presented the composer with his gold watch, ending years of estrangement. On May 29, 1892, at age nineteen, Rachmaninoff graduated from the Conservatory with highest honors in both composition and piano, officially becoming a "Free Artist."

1.3. Early Career and Setbacks

Upon graduating, Rachmaninoff continued to compose and signed a 500 RUB publishing contract with Gutheil, under which Aleko, Two Pieces (Op. 2), and Six Songs (Op. 4) were among the first works published. He had previously earned 15 RUB a month giving piano lessons at a girls' school. In the summer of 1892, he stayed at the estate of Ivan Konavalov, a wealthy landowner in the Kostroma Oblast, before moving back with the Satins in the Arbat District. Delays in payments from Gutheil led Rachmaninoff to seek other income sources, resulting in his public debut as a pianist at the Moscow Electrical Exhibition in September 1892. There, he premiered his landmark Prelude in C-sharp minor from his five-part piano composition Morceaux de fantaisie (Op. 3). He was paid 50 RUB for his appearance. The piece was enthusiastically received and became one of his most popular and enduring works, though its immense popularity later annoyed the composer. In 1893, he completed his tone poem The Rock, which he dedicated to Rimsky-Korsakov.

In 1893, Rachmaninoff spent a productive summer with friends at an estate in Kharkiv Oblast, where he composed several pieces, including Fantaisie-Tableaux (also known as Suite No. 1, Op. 5) and Morceaux de salon (Op. 10). In September, he published Six Songs (Op. 8), a collection of songs set to translations by Aleksey Pleshcheyev of Ukrainian and German poems. Rachmaninoff returned to Moscow, where Tchaikovsky agreed to conduct The Rock for an upcoming European tour. However, during a subsequent trip to Kyiv to conduct performances of Aleko, Rachmaninoff learned of Tchaikovsky's death from cholera. The news stunned him; later that day, he began work on his Trio élégiaque No. 2 for piano, violin, and cello as a tribute, completing it within a month. The music's somber aura reveals the depth of Rachmaninoff's grief for his idol. The piece debuted at the first concert devoted to Rachmaninoff's compositions on January 31, 1894.

Rachmaninoff entered a period of decline following Tchaikovsky's death. He lacked the inspiration to compose, and the management of the Grand Theatre lost interest in Aleko, dropping it from the program. To earn more money, Rachmaninoff returned to giving piano lessons, a task he disliked. In late 1895, he agreed to a three-month tour across Russia with Italian violinist Teresina Tua. The tour was unpleasant for the composer, and he quit before it ended, sacrificing his performance fees. In a desperate plea for money, he even pawned the gold watch given to him by Zverev.

In September 1895, before the tour began, Rachmaninoff completed his Symphony No. 1 (Op. 13), a work conceived in January and based on chants he had heard in Russian Orthodox church services. He had worked so intensely on it that he felt unable to return to composition until he heard the piece performed. This creative block lasted until October 1896, when a "rather large sum of money" belonging to someone else, but in Rachmaninoff's possession, was stolen during a train journey, forcing him to compose to recoup the losses. Among the pieces composed during this period were Six Choruses (Op. 15) and Six moments musicaux (Op. 16), his final completed composition for several months.

Rachmaninoff's fortunes took a severe turn following the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 on March 28, 1897, as part of the long-running Russian Symphony Concerts series. The piece was brutally panned by critic and nationalist composer César Cui, who likened it to a depiction of the seven plagues of Egypt, suggesting it would be admired by the "inmates" of a music conservatory in Hell. While other critics did not comment on the deficiencies of the performance, conducted by Alexander Glazunov, a memoir from Rachmaninoff's close friend, Alexander Ossovsky, suggested that Glazunov made poor use of rehearsal time, and the concert's program, which included two other premieres, was also a contributing factor. Other witnesses, including Rachmaninoff's wife, suggested that Glazunov, known for his alcoholism, might have been drunk. The fact that Saint Petersburg was a stronghold of the Nationalist School, which often clashed with the Moscow School to which Rachmaninoff belonged, may also have played a role in the harsh reception. Following the reaction to his first symphony, Rachmaninoff wrote in May 1897 that he was "not at all affected" by its lack of success or critical reaction, but felt "deeply distressed and heavily depressed by the fact that my Symphony... did not please me at all after its first rehearsal." He believed the performance was poor, particularly Glazunov's contribution. The piece was never performed again during Rachmaninoff's lifetime, though he revised it into a four-hand piano arrangement in 1898.

Rachmaninoff fell into a deep depression that lasted for three years, during which he experienced a severe writer's block and composed almost nothing. He described this time as "Like the man who had suffered a stroke and for a long time had lost the use of his head and hands." He made a living by giving piano lessons, which he disliked. A stroke of good fortune came when Savva Mamontov, a Russian industrialist and founder of the Moscow Private Russian Opera, offered Rachmaninoff the post of assistant conductor for the 1897-98 season. The cash-strapped composer accepted, making his opera conducting debut with Camille Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah on October 12, 1897. He met and formed a lifelong friendship with Feodor Chaliapin at this opera company. By the end of February 1899, Rachmaninoff attempted composition again, completing two short piano pieces, Morceau de Fantaisie and Fughetta in F major. Two months later, he traveled to London for the first time to perform and conduct, earning positive reviews. However, in late 1899, his depression worsened following an unproductive summer; he composed only one song, "Fate," which later became part of his Twelve Songs (Op. 21), and left compositions for a proposed return visit to London unfulfilled. In an attempt to revive his desire to compose, his aunt arranged for him to visit the esteemed writer Leo Tolstoy, whom Rachmaninoff greatly admired, hoping for words of encouragement. The visit was unsuccessful, doing nothing to help him regain his compositional fluency.

1.4. Recovery and Re-emergence

By 1900, Rachmaninoff had become so self-critical that, despite numerous attempts, composing had become nearly impossible. His aunt then suggested professional help, having herself received successful treatment from a family friend, physician, and amateur musician Nikolai Dahl. Rachmaninoff agreed without resistance. Between January and April 1900, Rachmaninoff underwent daily hypnotherapy and supportive therapy sessions with Dahl, specifically structured to improve his sleep patterns, mood, and appetite, and reignite his desire to compose. That summer, Rachmaninoff felt that "new musical ideas began to stir" and successfully resumed composition. He later stated that his recovery was thanks to Dahl's treatment, though there was a nearly three-month gap between the end of therapy and his resumption of composition, leading some to question the extent of the treatment's direct effect. During a concert tour with Chaliapin in Yalta, he met Anton Chekhov and formed a friendship, with Chekhov's praise providing significant encouragement.

His first fully completed work after this period, the Piano Concerto No. 2, was finished in April 1901 and dedicated to Dahl. After the second and third movements premiered in December 1900 with Rachmaninoff as the soloist, the entire piece was first performed in 1901 and was enthusiastically received, becoming one of his most popular compositions. The piece earned the composer a Glinka Award, the first of four he would receive throughout his life, and a 500 RUB prize in 1904.

Amid his professional career success, Rachmaninoff married Natalia Satina on May 12, 1902, after a three-year engagement. As they were first cousins, the marriage was forbidden under Canon law by the Russian Orthodox Church. Additionally, Rachmaninoff was not a regular church attendee and avoided confession, both necessary for a priest to sign a marriage certificate. To circumvent the church's opposition, the couple leveraged their military background and organized a small ceremony in a chapel at a Moscow suburb army barracks, with Siloti and cellist Anatoliy Brandukov as best men. They received the smaller of two houses at the Ivanovka estate as a wedding present and embarked on a three-month honeymoon across Europe. During this trip, he was inspired by Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle to compose his cantata Spring (Op. 20). Upon their return, they settled in Moscow, where Rachmaninoff resumed work as a music teacher at St. Catherine's Women's College and the Elizabeth Institute. By February 1903, he had completed his largest piano composition to date, the Variations on a Theme of Chopin (Op. 22). On May 14, 1903, the couple's first daughter, Irina Sergeyevna Rachmaninova, was born. During their summer break at Ivanovka, the family was struck with illness.

1.5. Conducting Activities

In 1904, Rachmaninoff made a career change, agreeing to become the conductor at the Bolshoi Theatre for two seasons. His tenure earned him a mixed reputation; he enforced strict discipline and demanded high standards of performance, leading some musicians to find him difficult, but critics praised his conducting. Influenced by Wagner, he pioneered the modern arrangement of orchestra players in the pit and the modern custom of standing while conducting. He also worked closely with each soloist on their part, even accompanying them on the piano. The theatre staged the premieres of his operas The Miserly Knight and Francesca da Rimini during his time there. He also performed as a soloist.

During his second season as conductor, Rachmaninoff began to lose interest in his post. The social and political unrest surrounding the Revolution of 1905 began to affect the performers and theatre staff, who staged protests and demands for improved wages and conditions. Rachmaninoff remained largely uninterested in the politics around him, and the revolutionary spirit made working conditions increasingly difficult. In February 1906, after conducting 50 performances in the first season and 39 in the second, Rachmaninoff submitted his resignation. He then took his family on an extended tour around Italy, hoping to complete new works, but illness struck his wife and daughter, prompting their return to Ivanovka. Financial issues soon arose following Rachmaninoff's resignation from his teaching posts, leaving him with only composition as an option for income.

1.6. Exile in Germany and First US Tour

Increasingly unhappy with the political turmoil in Russia and in need of seclusion from his lively social life to compose, Rachmaninoff and his family left Moscow for Dresden, Germany, in November 1906. The city became a favorite of both Rachmaninoff and Natalia, and they stayed there until 1909, returning to Russia only for their summer breaks at Ivanovka. Despite occasional periods of depression, apathy, and little faith in his work, Rachmaninoff began his Symphony No. 2 (Op. 27) in 1906, twelve years after the disastrous premiere of his first. In Paris, during the summer of 1907, he saw a black and white reproduction of The Isle of the Dead by Arnold Böcklin, which served as the inspiration for his orchestral work of the same name, Op. 29. He later saw the original painting in Leipzig, but found it disappointing, stating that his composition might not have been written had he seen the original first. His second daughter, Tatiana, was born in 1907.

While writing Symphony No. 2, Rachmaninoff and his family returned to Russia, but the composer detoured to Paris to participate in Sergei Diaghilev's season of Russian concerts in May 1907. His performance as the soloist in his Piano Concerto No. 2 with an encore of his Prelude in C-sharp minor was a triumphant success. Rachmaninoff regained his sense of self-worth following the enthusiastic reaction to the premiere of his Symphony No. 2 in early 1908, which earned him his second Glinka Award and 1.00 K RUB.

While in Dresden, Rachmaninoff agreed to perform and conduct in the United States as part of the 1909-10 concert season with conductor Max Fiedler and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He spent time during breaks at Ivanovka finishing a new piece specifically for the visit, his Piano Concerto No. 3, Op. 30, which he dedicated to Josef Hofmann. The tour included 26 performances, 19 as pianist and 7 as conductor, marking his first recitals without another performer on the program. His first appearance was at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts for a recital on November 4, 1909. The second performance of Piano Concerto No. 3 by the New York Symphony Orchestra was conducted by Gustav Mahler in New York City with the composer as soloist, an experience he personally treasured. Although the tour increased the composer's popularity in America, he declined subsequent offers due to the lengthy time away from Russia and his family.

Upon his return home in February 1910, Rachmaninoff became vice president of the Imperial Russian Musical Society (IRMS), whose president was a member of the royal family. Later in 1910, Rachmaninoff completed his choral work Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Op. 31, but it was banned from performance as it did not adhere to the format of a typical liturgical church service. For two seasons between 1911 and 1913, Rachmaninoff was appointed permanent conductor of the Philharmonic Society of Moscow; he helped raise its profile and increase audience numbers and receipts. In 1912, Rachmaninoff resigned from the IRMS when he learned that a musician in an administrative post was dismissed for being Jewish, demonstrating his commitment to artistic integrity over political expediency.

Soon after his resignation, an exhausted Rachmaninoff sought time for composition and took his family on holiday to Switzerland. After one month, they left for Rome for a visit that became a particularly tranquil and influential period for the composer. He lived alone in a small apartment on Piazza di Spagna, the same building where Tchaikovsky had stayed, while his family resided at a boardinghouse. While there, he received an anonymous letter containing a Russian translation of Edgar Allan Poe's poem The Bells by Konstantin Balmont, which affected him greatly, and he began work on his choral symphony of the same title, Op. 35, based on it. This anonymous sender was later identified as Thekla Russo. Rachmaninoff's period of composition ended abruptly when both his daughters contracted serious cases of typhoid and were treated in Berlin due to their father's greater trust in German doctors. After six weeks, the Rachmaninoffs returned to their Moscow flat. The composer conducted The Bells at its premiere in Saint Petersburg in late 1913.

In January 1914, Rachmaninoff began a concert tour of England which was enthusiastically received. However, he became afraid to travel alone following the unexpected death of Raoul Pugno from a heart attack in his hotel room. Following the outbreak of World War I later that year, his position as Inspector of Music at the Nobility High School for Girls prevented him from joining the army. Nevertheless, the composer made regular charitable donations for the war effort. In 1915, Rachmaninoff completed his second major choral work, All-Night Vigil (Op. 37). It was received so warmly at its Moscow premiere, held to aid war relief, that four subsequent performances were quickly scheduled.

Alexander Scriabin's death in April 1915 was a tragedy for Rachmaninoff, who embarked on a piano recital tour devoted to his friend's compositions to raise funds for Scriabin's financially struggling widow. This marked his first public performances of works other than his own. During a vacation in Finland that summer, Rachmaninoff learned of Taneyev's death, a loss that affected him greatly. By year's end, he had finished his 14 Romances, Op. 34, whose final section, Vocalise, became one of his most popular pieces.

1.7. Russian Revolution and Emigration

On the day the February Revolution began in Saint Petersburg, March 8, 1917, Rachmaninoff performed a piano recital in Moscow in aid of wounded Russian soldiers. He returned to Ivanovka two months later, finding it in chaos after a group of Social Revolutionary Party members seized it as their own communal property. Despite having invested most of his earnings in the estate, Rachmaninoff left the property after three weeks, vowing never to return. It was soon confiscated by the communist authorities and became derelict. In June 1917, Rachmaninoff asked Siloti to produce visas for him and his family so they could leave Russia, but Siloti was unable to help. After a break with his family in the more peaceful Crimea, Rachmaninoff's concert performance in Yalta on September 5, 1917, was to be his last in Russia. Upon returning to Moscow, the political tension surrounding the October Revolution found the composer keeping his family safe indoors and being involved in a collective at his apartment building where he attended committee meetings and kept guard at night. He completed revisions to his Piano Concerto No. 1 amidst gunshots and rallies outside.

Amidst such turmoil, Rachmaninoff received an unexpected offer to perform ten piano recitals across Scandinavia, which he immediately accepted, using it as an excuse to obtain permits so he and his family could leave the country. On December 22, 1917, they left Saint Petersburg by train to the Finnish border, from where they traveled through Finland on an open sled and train to Helsinki. Carrying what they could pack into their small suitcases, Rachmaninoff brought some sketches of compositions and scores to the first act of his unfinished opera Monna Vanna and Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Golden Cockerel. This minimal luggage suggested he intended to return soon. They arrived in Stockholm, Sweden, on December 24. He would never set foot on Russian soil again.

In January 1918, they relocated to Copenhagen, Denmark, and, with the help of friend and composer Nikolai Struve (1875-1920), settled on the ground floor of a house. In debt and in need of money, the 44-year-old Rachmaninoff chose performing as his main source of income, as a career solely in composition was too restrictive. His piano repertoire was small, which prompted him to begin regular practice of his technique and learning new pieces. Rachmaninoff toured between February and October 1918.

During the Scandinavian tour, Rachmaninoff received three offers from the United States: to become the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra for two years, to conduct 110 concerts in 30 weeks for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and to give 25 piano recitals. He was worried about such a commitment in an unfamiliar country and had few good memories from his debut tour in 1909, so he declined all three. Not long after his decision, Rachmaninoff reconsidered, recognizing the financial advantages of the United States, as he could not support his family through composition alone. Unable to afford the travel fees, he was sent an advance loan for the journey by Russian banker and fellow émigré Alexander Kamenka. Money was also received from friends and admirers; pianist Ignaz Friedman contributed 2.00 K USD. On November 1, 1918, the Rachmaninoffs boarded the SS Bergensfjord in Oslo, Norway, bound for New York City, arriving eleven days later. News of the composer's arrival spread, causing a crowd of musicians, artists, and fans to gather outside The Sherry-Netherland hotel, where he was staying.

1.8. Life in the United States and Later Years

Rachmaninoff quickly attended to business, hiring pianist Dagmar de Corval Rybner as his secretary, interpreter, and aide in navigating American life. He reunited with Josef Hofmann, who informed several concert managers that the composer was available and suggested he choose Charles Ellis as his booking agent. Ellis organized 36 performances for Rachmaninoff for the upcoming 1918-1919 concert season; the first, a piano recital, took place on December 8 at Providence, Rhode Island. Rachmaninoff, still recovering from a case of the Spanish flu, included his arrangement of "The Star-Spangled Banner" in the program. Before the tour, he had received offers from numerous piano manufacturers to tour with their instruments; he chose Steinway, the only one that did not offer him money. Steinway's association with Rachmaninoff continued for the rest of his life.

After the first tour ended in April 1919, Rachmaninoff took his family on a break to San Francisco. He recuperated and prepared for the upcoming season, a cycle he would adopt for most of his remaining life. As a touring performer, Rachmaninoff became financially secure without much difficulty, and the family lived an upper-middle-class life with servants, a chef, and a chauffeur. They recreated the atmosphere of Ivanovka in their New York City apartment by entertaining Russian guests, employing Russians, and continuing to observe Russian customs. Despite being able to speak some English, Rachmaninoff had his correspondence translated into Russian. He enjoyed personal luxuries, including quality tailored suits and the latest models of cars, particularly high-speed sports cars like Mercedes and Bugatti. He invested 5.00 K USD in the Sikorsky company, which was developing helicopters. After moving to the US, he hired a Russian chauffeur as he could not obtain a driver's license.

In 1920, Rachmaninoff signed a recording contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor), which earned him much-needed income and began his longtime association with RCA. During a family holiday in Goshen, New York, that summer, he learned of Struve's accidental death, prompting Rachmaninoff to strengthen his ties with those still in Russia by arranging with his bank to send regular money and food parcels to his family, friends, students, and those in need. In early 1921, Rachmaninoff applied for documentation to visit Russia, the only time he would do so after leaving the country, but progress ceased when he underwent surgery for pain in his right temple. The operation failed to relieve his symptoms, and relief only came after having dental work years later. After leaving the hospital, he purchased an apartment on 33 Riverside Drive on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, overlooking the Hudson River.

Rachmaninoff's first visit to Europe since emigrating occurred in May 1922, with concerts in London. This was followed by the Rachmaninoffs and the Satins reuniting in Dresden, after which the composer prepared for a hectic 1922-1923 concert season of 71 performances in five months. For a while, he rented a railway carriage fitted with a piano and belongings to save time with suitcases, though he quickly abandoned sleeping on it due to noise. In 1924, Rachmaninoff declined an invitation to become conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. On March 10, 1924, he was invited to the White House to perform for President Calvin Coolidge. In the following year, after the death of his daughter Irina's husband, Pyotr Volkonsky, who was with child at the time (their granddaughter would later be named Sophie Volkonsky), Rachmaninoff founded TAIR (Tatiana and Irina), a Paris publishing company named after his daughters that specialized in works by himself and other Russian composers.

Rachmaninoff's life as a touring performer, and the demanding schedules that came with it, caused his compositional output to slow significantly. In the 24 years between his arrival in the US and his death, he completed just six new pieces, revised some of his earlier works, and wrote piano transcriptions for his live repertoire. He admitted that by leaving Russia, "I left behind my desire to compose: losing my country, I lost myself also." In 1923, he wrote to a friend, "I have not composed for five years... I don't think I can do anything new until I 'wake up' or 'reborn'." When asked by Nikolai Medtner why he wasn't composing, he replied, "I haven't heard the rustling of rye or the murmuring of birches for years. How can I compose without melodies?" Nevertheless, in 1926, having concentrated on touring for the past eight years, he took a year off and completed the Piano Concerto No. 4, which he had started in 1917, and Three Russian Songs, which he dedicated to Leopold Stokowski.

Rachmaninoff sought the company of fellow Russian musicians and befriended pianist Vladimir Horowitz in 1928. The men remained supportive of each other's work, each making a point of attending concerts given by the other, and Horowitz remained a champion of Rachmaninoff's works, particularly his Piano Concerto No. 3. In 1930, in a rare occurrence, Rachmaninoff allowed Italian composer Ottorino Respighi to orchestrate pieces from his Études-Tableaux, Op. 33 (1911) and the Études-Tableaux, Op. 39 (1917), providing Respighi with the inspirations behind the compositions. However, Rachmaninoff was disappointed with the finished orchestrations and remained silent on their critical reception. By December 1931, his daughter was engaged to marry Boris Conus, with a second grandchild, Alexander Conus, born later to the couple. In 1931, Rachmaninoff and several others signed an article in The New York Times that criticized the cultural policies of the Soviet Union. The composer's music suffered a boycott in the Soviet Union as a result of the backlash in the Soviet press, lasting until 1933.

From 1929 to 1931, Rachmaninoff spent his summers in France at Clairefontaine-en-Yvelines near Rambouillet, meeting with fellow Russian émigrés and his daughters. By 1930, his desire to compose had returned, and he sought a new location to write new pieces. He bought a plot of land near Hertenstein on the banks of Lake Lucerne, Switzerland, and oversaw the construction of his home, which he named Villa Senar after the first two letters of his and his wife's names, adding the "r" from the family name. Rachmaninoff spent his summers at Villa Senar until 1939, often with his daughters and grandchildren, with whom he would drive his motorboat on Lake Lucerne, one of his favorite activities. In the comfort of his own home, Rachmaninoff completed Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in 1934 and the Symphony No. 3 in 1936.

In October 1932, Rachmaninoff began a demanding concert season that consisted of 50 performances. The tour marked the fortieth anniversary of his debut as a pianist, for which several of his Russian friends now living in America sent him a scroll and wreath in celebration. The frail economic situation in the US resulted in the composer performing to smaller audiences, and he lost money in his investments and shares. The European leg of this tour in 1933 saw Rachmaninoff celebrate his sixtieth birthday among fellow musicians and friends, after which he retreated to Villa Senar for the summer. In May 1934, Rachmaninoff underwent a minor operation, and two years later, he retreated to Aix-les-Bains in France to improve his arthritis. During a visit to Villa Senar in 1937, Rachmaninoff entered talks with choreographer Michel Fokine about a ballet based on Niccolò Paganini that was to feature his rhapsody. It premiered in London in 1939 with the composer's daughters in attendance. In 1938, Rachmaninoff performed his Piano Concerto No. 2 at a charity jubilee concert at London's Royal Albert Hall to celebrate Henry Wood, founder of the Promenade concerts and an admirer of Rachmaninoff's who wanted him to be the show's only soloist. Rachmaninoff agreed, so long as the performance was not broadcast on the radio, due to his aversion to the medium.

The 1939-40 concert season saw Rachmaninoff perform fewer concerts than usual, totaling 43 appearances, mostly in the US. The tour continued with dates across England, after which Rachmaninoff visited his daughter Tatyana in Paris, followed by a return to Villa Senar. He was unable to perform for a while after slipping on the floor at the villa and injuring himself. He recovered enough to perform at the Lucerne International Music Festival on August 11, 1939. It was to be his final concert in Europe. With World War II imminent, he returned to Paris two days later, where he, his wife, and two daughters were together for the last time before the composer left Europe on August 23. With financial help from Rachmaninoff, philosopher Ivan Ilyin was able to pay bail and settle in Switzerland. Rachmaninoff would support the Soviet Union's war effort against Nazi Germany from mid-1941 onwards, donating receipts from many of his concerts for the benefit of the Red Army. He directly handed the donations to the Soviet consul in New York.

Upon his return to the US, Rachmaninoff performed with the Philadelphia Orchestra in New York City with conductor Eugene Ormandy on November 26 and December 3, 1939, as part of the orchestra's special series of concerts dedicated to the composer in celebration of the thirtieth anniversary of his US debut. The final concert on December 10 saw Rachmaninoff conduct his Symphony No. 3 and The Bells, marking his first conducting performance since 1917. The concert season left Rachmaninoff tired, and he spent the summer resting from minor surgery at Orchard's Point, an estate near Huntington, New York on Long Island. During this period, Rachmaninoff completed his final composition, the Symphonic Dances, Op. 45, which was premiered by Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra in January 1941, with Rachmaninoff in attendance. In December 1939, Rachmaninoff began an extensive recording period which lasted until February 1942 and included his Piano Concerto Nos. 1 and 3 and Symphony No. 3 at the Philadelphia Academy of Music.

1.9. Health Decline and Death

In early 1942, Rachmaninoff was advised by his doctor to relocate to a warmer climate to improve his health after suffering from sclerosis, lumbago, neuralgia, high blood pressure, and headaches. After completing his final studio recording sessions during this time in February, a move to Long Island fell through after the composer and his wife expressed a greater interest in California, and initially settled in a leased home on Tower Road in Beverly Hills in May. In June, they purchased a home at 610 North Elm Drive in Beverly Hills, living close to Horowitz, who would often visit and perform piano duets with Rachmaninoff. Later in 1942, Rachmaninoff invited Igor Stravinsky to dinner, the two sharing their worries of a war-torn Russia and their children in France.

Shortly after a performance at the Hollywood Bowl in July 1942, Rachmaninoff was suffering from lumbago and fatigue. He informed his doctor, Alexander Golitsyn, that the upcoming 1942-43 concert season would be his last, in order to dedicate his time to composition. The tour began on October 12, 1942, and the composer received many positive reviews from critics despite his deteriorating health. Rachmaninoff and his wife Natalia were among the 220 people who became naturalized American citizens at a ceremony held in New York City on February 1, 1943. Later that month, he complained of persistent cough and back pain; a doctor diagnosed him with pleurisy and advised that a warmer climate would aid in his recovery. Rachmaninoff opted to continue with touring, but felt so ill during his travels to Florida that the remaining dates were canceled, and he returned to California by train, where an ambulance took him to hospital. It was then that Rachmaninoff was diagnosed with an aggressive form of melanoma, which had already metastasized throughout his body, though he was not informed of the diagnosis. His wife took Rachmaninoff home, where he reunited with his daughter Irina. His last appearances as a concerto soloist, playing Beethoven's First Piano Concerto and his Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, were on February 11 and 12 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Hans Lange, and on February 17, at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Tennessee, he gave his last recital as a pianist.

Rachmaninoff's health rapidly declined in the last week of March 1943. He lost his appetite, had constant pain in his arms and sides, and found it increasingly difficult to breathe. On March 26, the composer lost consciousness, and he died two days later at his home in Beverly Hills, at age 69, at 1:30 AM. A message from several Moscow composers with greetings had arrived too late for Rachmaninoff to read it. His funeral took place at the Holy Virgin Mary Russian Orthodox Church on Micheltorena Street in Silver Lake. In his will, Rachmaninoff wished to be buried at Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, where Scriabin, Taneyev, and Anton Chekhov were buried, but his American citizenship and the wartime situation made that impossible. Instead, he was interred at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. In 1958, Van Cliburn, after winning the first International Tchaikovsky Competition, brought soil from Tchaikovsky's grave in Moscow to place on Rachmaninoff's grave.

After Rachmaninoff's death, poet Marietta Shaginyan published fifteen letters they exchanged from their first contact in February 1912 and their final meeting in July 1917. The nature of their relationship bordered on romantic but was primarily intellectual and emotional. Shaginyan and the poetry she shared with Rachmaninoff have been cited as the inspiration for his Six Songs, Op. 38.

2. Musical Works

Sergei Rachmaninoff's musical output is characterized by its late Romantic style, rich melodic content, and profound emotional depth, often featuring the piano prominently.

2.1. Influences

A major influence on Rachmaninoff as a composer was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. This influence can be seen throughout Rachmaninoff's early compositions, such as in his Youth Symphony, which is reminiscent of Tchaikovsky's late symphonies; sections of his symphonic poem Prince Rostislav, which emulates The Tempest and Romeo and Juliet; and his youthful Three Nocturnes, the third of which contains a chordal section very similar to the opening of Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto. His first opera, Aleko, shows the influence of Tchaikovsky in both its harmonies and its allusions and references to Eugene Onegin. Tchaikovsky was also particularly influential on Rachmaninoff's melodic writing, though musicologist Stephen Walsh describes Rachmaninoff's melodies as lacking the range or length of Tchaikovsky's. Rachmaninoff dedicated his Suite No. 1 for two pianos to Tchaikovsky. When Tchaikovsky died suddenly in 1893, Rachmaninoff composed his Trio élégiaque No. 2 as a tribute, mirroring Tchaikovsky's own piano trio dedicated to Nikolai Rubinstein.

The influence of Anton Arensky, who taught Rachmaninoff for five years at the Moscow Conservatory, can be seen in the composer's early compositions. This influence is evident, for example, in his symphonic poem Prince Rostislav, dedicated to Arensky, and a number of compositions from his student years may have been written as exercises for his teacher. According to biographer Barrie Martyn, the "obviously Russian character" and "Tchaikovskian lyricism" of Arensky's music were elements also present in Rachmaninoff's compositional style. Sergei Taneyev, Rachmaninoff's teacher in counterpoint at the Moscow Conservatory, was also an influence on his early compositions. Rachmaninoff would bring his compositions to Taneyev for approval up until Taneyev's death in 1915. In his later style, the influence of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov can be seen in the increasingly chromatic harmonies and thinner orchestration in Rachmaninoff's compositions from his Third Piano Concerto onwards. Other Russian composers like Mily Balakirev and Modest Mussorgsky also influenced his work.

Rachmaninoff's love for the sound of church bells, which he heard frequently in Novgorod and Moscow during his childhood, deeply permeated his compositions. This "bell-like" sound is a distinctive feature, notably in his choral symphony The Bells, the Second Piano Concerto, the E-flat major Étude-Tableaux (Op. 33, No. 7), and the B minor Prelude (Op. 32, No. 10). He was also fond of Russian Orthodox chants, using them most perceptibly in his Vespers, but many of his melodies found their origins in these chants, such as the opening melody of the First Symphony.

2.2. Compositional Style

Rachmaninoff's style was initially influenced by Tchaikovsky. By the mid-1890s, however, his compositions began showing a more individual tone. His First Symphony has many original features. Its brutal gestures and uncompromising power of expression were unprecedented in Russian music at the time. Its flexible rhythms, sweeping lyricism, and stringent economy of thematic material were all features he kept and refined in subsequent works. Following the poor reception of the symphony and three years of inactivity, Rachmaninoff's individual style developed significantly. He started leaning towards broadly lyrical, often passionate melodies. His orchestration became subtler and more varied, with textures carefully contrasted. Overall, his writing became more concise.

Especially important is Rachmaninoff's use of unusually widely spaced chords for bell-like sounds. He also frequently incorporated Russian Orthodox chants, often as melodic foundations. The frequently used motif of the Dies irae, often just fragments of its first phrase, appears in many of his major works, including The Bells, The Isle of the Dead, and his symphonies.

Rachmaninoff had a great command of counterpoint and fugal writing, thanks to his studies with Taneyev. The occurrence of the Dies irae in the Second Symphony (1907) is a small example of this. Very characteristic of his writing is chromatic counterpoint. This talent was paired with a confidence in writing in both large- and small-scale forms. The Third Piano Concerto especially shows structural ingenuity, while each of the preludes grows from a tiny melodic or rhythmic fragment into a taut, powerfully evocative miniature, crystallizing a particular mood or sentiment while employing a complexity of texture, rhythmic flexibility, and a pungent chromatic harmony. His melodies often begin on the second beat, a notable characteristic compared to other composers.

His compositional style had already begun changing before the October Revolution deprived him of his homeland. The harmonic writing in The Bells, composed in 1913 but not published until 1920, became as advanced as in any of the works Rachmaninoff would write in Russia, partly because the melodic material has a harmonic aspect that arises from its chromatic ornamentation. Further changes are apparent in the revised First Piano Concerto, which he finished just before leaving Russia, as well as in the Op. 38 songs and Op. 39 Études-Tableaux. In both these sets, Rachmaninoff was less concerned with pure melody than with coloring. His near-Impressionist style perfectly matched the texts by symbolist poets. The Op. 39 Études-Tableaux are among the most demanding pieces he wrote for any medium, both technically and in the sense that the player must see beyond any technical challenges to a considerable array of emotions, then unify all these aspects.

The composer's friend Vladimir Wilshaw noticed this compositional change continuing in the early 1930s, with a difference between the sometimes very extroverted Op. 39 Études-Tableaux (the composer had broken a string on the piano at one performance) and the Variations on a Theme of Corelli (Op. 42, 1931). The variations show an even greater textural clarity than in the Op. 38 songs, combined with a more abrasive use of chromatic harmony and a new rhythmic incisiveness. This would be characteristic of all his later works-the Piano Concerto No. 4 (Op. 40, 1926) is composed in a more emotionally introverted style, with greater clarity of texture. Nevertheless, some of his most beautiful (nostalgic and melancholy) melodies occur in the Third Symphony, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, and Symphonic Dances. Music theorist Joseph Yasser, as early as 1951, uncovered progressive tendencies in Rachmaninoff's compositions, noting his use of an intra-tonal chromaticism that contrasted with the inter-tonal chromaticism of Wagner and the extra-tonal chromaticism of more radical twentieth-century composers like Arnold Schoenberg.

Rachmaninoff stated in a 1941 interview that he never consciously tried to be original, romantic, or nationalistic. He simply wrote down the music he heard in his mind as naturally as possible, aiming to express what was in his heart concisely and directly.

2.3. Major Works

Rachmaninoff's complete works include 45 opus-numbered compositions, with 39 of them written before the 1917 Russian Revolution. His complete works are copyrighted by Boosey & Hawkes.

2.3.1. Operas

Rachmaninoff completed three one-act operas: Aleko (1892), The Miserly Knight (1903), and Francesca da Rimini (1904). He started three others, notably Monna Vanna, based on the work by Maurice Maeterlinck, but dropped the project after completing Act I in piano vocal score in 1908 due to copyright issues. Aleko is regularly performed and has been recorded and filmed. The Miserly Knight adheres to Pushkin's "little tragedy." Francesca da Rimini was described by the composer as a "symphonic opera" because of its long interludes.

2.3.2. Symphonies

Rachmaninoff composed three numbered symphonies, widely spaced chronologically, representing distinct phases in his compositional development.

- Symphony in D minor (1891): A single-movement work, unfinished beyond its first movement, often referred to as the "Youth Symphony."

- Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 13 (1895): This work was a monumental failure at its premiere. The score was believed lost for many years after Rachmaninoff tore it up, but it was reconstructed after his death from orchestral parts found in the Leningrad Conservatory.

- Symphony No. 2 in E minor, Op. 27 (1906-1907): This symphony has been the most popular of the three since its first performance, with its third movement being particularly well-known for its lyrical melody.

- Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 44 (1936): Composed after he left Russia, this symphony is noted for its intense expression of longing for his homeland. Rachmaninoff himself recorded this work.

2.3.3. Piano Concertos and Rhapsody

Rachmaninoff wrote five works for piano and orchestra: four concertos and the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Of the concertos, the Second and Third are the most popular and are considered among the most challenging and significant works in the virtuoso Romantic piano concerto repertoire.

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 (1891, revised 1917): This was his first piano concerto, dedicated to Alexander Siloti.

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 (1900-1901): Dedicated to Nikolai Dahl, this concerto is one of his most famous and popular works, widely used in films like Brief Encounter and The Seven Year Itch.

- Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30 (1909): Dedicated to Josef Hofmann, this concerto is renowned for its technical demands and is a favorite among virtuoso pianists.

- Piano Concerto No. 4 in G minor, Op. 40 (1926, revised 1928 and 1941): This work, composed after his emigration, features a more emotionally detached style.

- Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in A minor, Op. 43 (1934): A set of variations on a theme by Paganini, its 18th variation, composed in inversion, is particularly famous for its lyricism.

2.3.4. Orchestral Works

Rachmaninoff also composed a number of works for orchestra alone.

- Scherzo in D minor (1887)

- Symphonic poem Prince Rostislav (1891)

- Symphonic fantasy The Rock, Op. 7 (1893)

- Caprice bohémien, Op. 12 (1894): A capriccio on Gypsy themes.

- Symphonic poem The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 (1909): Inspired by Arnold Böcklin's painting.

- Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 (1941): His last major composition, premiered by the Philadelphia Orchestra.

2.3.5. Solo Piano Works

As Rachmaninoff was a skilled pianist, a large portion of his compositional output consists of works for solo piano. These works are known for their technical difficulty and expressive depth. Only seven pianists have successfully recorded his complete piano works to date.

- Morceaux de fantaisie, Op. 3 (1892): Includes the famous Prelude in C-sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2, which brought him early fame.

- Morceaux de salon, Op. 10 (1894)

- Six moments musicaux, Op. 16 (1896)

- Variations on a Theme of Chopin in C minor, Op. 22 (1902-1903): Based on Chopin's Prelude in C minor (Op. 28, No. 20).

- 24 Preludes: Comprising ten preludes in Op. 23 (1901-1903) and thirteen in Op. 32 (1910), traversing all 24 major and minor keys.

- Piano Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 28 (1907): A large-scale and virtuosic work.

- Études-Tableaux, Op. 33 (1911) and Op. 39 (1916-1917): These "study pictures" are exceptionally demanding, both technically and emotionally. Ottorino Respighi orchestrated five of these.

- Piano Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36 (1913, revised 1935): Another monumental and virtuosic piano sonata.

- Variations on a Theme of Corelli in D minor, Op. 42 (1931)

- Works for two pianos, four hands, including two Suites (the first subtitled Fantasie-Tableaux), a version of the Symphonic Dances (Op. 45), and an arrangement of the C-sharp minor Prelude, as well as a Russian Rhapsody, and he arranged his First Symphony for piano four hands. Both these works were published posthumously.

2.3.6. Vocal and Choral Works

Rachmaninoff made significant contributions to choral and vocal music.

- Cantata Spring, Op. 20 (1902)

- Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Op. 31 (1910): A major a cappella choral work for the Orthodox Church, initially banned for not following traditional liturgical format.

- Choral symphony The Bells, Op. 35 (1913): Based on Edgar Allan Poe's poem, it features three soloists, choir, and orchestra.

- All-Night Vigil (also known as the Vespers), Op. 37 (1915): Another major a cappella choral work, considered one of his finest. Rachmaninoff requested its fifth movement be sung at his funeral.

- Three Russian Songs, Op. 41 (1927)

- 83 songs (románsy in Russian) for voice and piano, all written before 1917. Most were set to texts by Russian romantic writers and poets like Pushkin, Lermontov, Fet, Chekhov, and Aleksey Tolstoy. His most popular song is the wordless Vocalise, Op. 34, No. 14, which he later arranged for orchestra.

2.3.7. Chamber Music

Rachmaninoff, like many Russian composers of his time, wrote relatively little chamber music.

- Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor (1892)

- Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor, Op. 9 (1893): A memorial tribute to Tchaikovsky.

- String Quartet No. 1 (1889-1890, premiered 1945, published 1947)

- String Quartet No. 2 (1896, published same year as No. 1)

- Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 19 (1901): The piano tends to dominate the ensemble in his chamber works.

- Morceaux de salon for violin and piano, Op. 6 (1893)

3. Pianist

Rachmaninoff ranked among the finest pianists of his time, alongside Leopold Godowsky, Ignaz Friedman, Moriz Rosenthal, Josef Lhévinne, Ferruccio Busoni, and Josef Hofmann. He was famed for possessing a clean and virtuosic technique.

3.1. Performance Technique and Tone

Rachmaninoff's playing was marked by precision, rhythmic drive, notable use of staccato, and the ability to maintain clarity when playing works with complex textures. He applied these qualities in music by Chopin, including the B-flat minor Piano Sonata. Only Josef Hofmann and Josef Lhévinne shared this kind of clarity with him. All three men had Anton Rubinstein as a model for this kind of playing-Hofmann as a student of Rubinstein's, Rachmaninoff from hearing his famous series of historical recitals in Moscow while studying with Zverev, and Lhévinne from hearing and playing with him.

Rachmaninoff possessed unusually large hands, with which he could easily maneuver through the most complex chordal configurations. He could reportedly play a twelfth with his left hand (C, E-flat, G, C, and G) and his right hand could play C (index), E (thumb), G, C, and E. His hand span was approximately 12 in (30.5 cm), commensurate with his height of 6.5 ft (1.98 m). His left hand technique was unusually powerful. His playing was marked by definition-where other pianists' playing became blurry-sounding from overuse of the pedal or deficiencies in finger technique, Rachmaninoff's textures were always crystal clear.

Of Rachmaninoff's tone, Arthur Rubinstein wrote: "I was always under the spell of his glorious and inimitable tone which could make me forget my uneasiness about his too rapidly fleeting fingers and his exaggerated rubatos. There was always the irresistible sensuous charm, not unlike Fritz Kreisler's." Coupled with this tone was a vocal quality not unlike that attributed to Chopin's playing. With Rachmaninoff's extensive operatic experience, he was a great admirer of fine singing. As his records demonstrate, he possessed a tremendous ability to make a musical line sing, no matter how long the notes or how complex the supporting texture, with most of his interpretations taking on a narrative quality. With the stories he told at the keyboard came multiple voices-a polyphonic dialogue, not the least in terms of dynamics. His 1940 recording of his transcription of the song "Daisies" captures this quality extremely well. On the recording, separate musical strands enter as if from various human voices in eloquent conversation. This ability came from an exceptional independence of fingers and hands.

The size of his hands, along with his considerable height, slender frame, long limbs, narrow head, prominent ears, and thin nose, has led to speculation that he may have had Marfan syndrome, a hereditary disorder of the connective tissue. This syndrome could account for several minor ailments he suffered throughout his life, including back pain, arthritis, eye strain, and bruising of the fingertips. However, an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine pointed out that Rachmaninoff did not show many of the typical signs of Marfan syndrome and instead suggested that he may have had acromegaly, which, the article speculated, could account for stiffness he experienced in his hands, for the repeated periods of depression, and possibly even for his melanoma.

3.2. Interpretations and Recordings

Rachmaninoff's repertoire, excluding his own works, consisted mainly of standard 19th-century virtuoso pieces plus music by Bach, Beethoven, Borodin, Debussy, Grieg, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, and Tchaikovsky. The two pieces Rachmaninoff singled out for praise from Anton Rubinstein's concerts-Beethoven's Appassionata and Chopin's Funeral March Sonata-became cornerstones for his own recital programs. Rachmaninoff biographer Barrie Martyn points out similarities between written accounts of Rubinstein's interpretation and Rachmaninoff's audio recording of the Chopin sonata.

Regardless of the music, Rachmaninoff always planned his performances carefully. He based his interpretations on the theory that each piece of music has a "culminating point." Regardless of where that point was or at which dynamic within that piece, the performer had to know how to approach it with absolute calculation and precision; otherwise, the whole construction of the piece could crumble and the piece could become disjointed. This was a practice he learned from Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin, a staunch friend. Paradoxically, Rachmaninoff often sounded as if he was improvising, though he actually was not. While his interpretations were mosaics of tiny details, when those mosaics came together in performance, they might, according to the tempo of the piece being played, fly past at great speed, giving the impression of instant thought.

One advantage Rachmaninoff had in this building process over most of his contemporaries was in approaching the pieces he played from the perspective of a composer rather than that of an interpreter. He believed "interpretation demands something of the creative instinct. If you are a composer, you have an affinity with other composers. You can make contact with their imaginations, knowing something of their problems and their ideals. You can give their works color. That is the most important thing for me in my interpretations, color. So you make music live. Without color it is dead." Nevertheless, Rachmaninoff also possessed a far better sense of structure than many of his contemporaries, such as Hofmann, or the majority of pianists from the previous generation, judging from their respective recordings.

A recording that showcases Rachmaninoff's approach is the Liszt Second Polonaise, recorded in 1925. Rachmaninoff's performance is far more taut and concentrated than that of Percy Grainger, who had been influenced by the composer and Liszt specialist Ferruccio Busoni. The Russian's drive and monumental conception bear a considerable difference to the Australian's more delicate perceptions. Grainger's textures are elaborate, while Rachmaninoff shows the filigree as essential to the work's structure, not simply decorative.

Upon arriving in America, Rachmaninoff's poor financial situation prompted him in 1919 to record a selection of piano pieces for Edison Records on their "Diamond Disc" records, in a limited contract for ten released sides. Rachmaninoff felt his performances varied in quality and requested final approval prior to a commercial release. Edison agreed, but still issued multiple takes, an unusual practice that was standard at Edison Records. Rachmaninoff and Edison Records were pleased with the released discs and wished to record more, but Edison refused, stating the ten sides were sufficient. This, in addition to technical issues in the recordings and Edison's perceived lack of musical taste, led to Rachmaninoff's annoyance with the company, and as soon as his contract ended, he left Edison Records.

In 1920, Rachmaninoff signed a contract with the Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor). Unlike Edison, the company was pleased to comply with his requests and proudly advertised Rachmaninoff as one of their prominent recording artists. He continued to record for Victor until 1942, when the American Federation of Musicians imposed a recording ban on their members in a strike over royalty payments. Rachmaninoff died in March 1943, over a year and a half before RCA Victor settled with the union and resumed commercial recording activity.

When Rachmaninoff recorded his works, he sought perfection, often re-recording them until he was satisfied. Particularly renowned are his renditions of Schumann's Carnaval and Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 2, which many consider the finest performance of that work, along with many shorter pieces. He recorded all four of his piano concertos with the Philadelphia Orchestra; the first, third, and fourth concertos were recorded with Eugene Ormandy in 1939-41, and two versions of the second concerto with Leopold Stokowski in 1924 and 1929. He also made a recording of the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, soon after its first performance (1934) with the Philadelphians under Stokowski, in addition to three recordings he made as conductor with the Philadelphia Orchestra, playing his own Third Symphony, his symphonic poem Isle of the Dead, and his orchestration of Vocalise.

Rachmaninoff also recorded a number of piano rolls on the reproducing piano of the American Piano Company (Ampico), producing a total of 35 piano rolls from 1919 to 1929, 12 of which were of his own compositions. He began recording rolls for Ampico in March 1919, upon the suggestion of his friend Fritz Kreisler, and continued doing so, on and off, until around February 1929, though his last roll, of Chopin's Scherzo No. 2, was not published until October 1933. Of the works he produced piano rolls for, 29 he also made gramophone recordings of, and these provide evidence for Rachmaninoff's consistency of interpretation. In addition, there also survives an unpublished piano roll of the second movement of his Second Piano Concerto, and may be indicative of Rachmaninoff having made other rolls. In December 1931, Rachmaninoff participated in an experimental recording by Bell Telephone Laboratories in Philadelphia, where his performance of Liszt's Ballade No. 2 and the fourth movement of Weber's Piano Sonata No. 1 were transmitted via telephone line to New York for recording, though these recordings are not extant.

4. Conductor

Rachmaninoff was also a significant conductor, though his work in this role is often overshadowed by his achievements as a composer and pianist.

4.1. Conducting Activities

Apart from several early performances, including two of his opera Aleko in 1893, Rachmaninoff first began conducting professionally in 1897 and performed as a conductor every year until 1914. After leaving Russia permanently in 1917, Rachmaninoff prioritized performing as a pianist over conducting, giving only seven more recitals as a conductor until the end of his life.

Rachmaninoff was noted for his restraint in conducting and for the "simple and unpolished" manner in which he gestured to the orchestra. According to Alexander Goldenweiser, his performances as a conductor were much stricter and less rhythmically free than his performances on the piano. In Nikolai Medtner's estimation, he was "the greatest Russian conductor." Music critic Yuri Engel praised him as a "born genius conductor" comparable to Arthur Nikisch, Gustav Mahler, and Édouard Colonne.

In addition to his own works, Rachmaninoff conducted repertoire primarily from fellow Russian composers, such as Borodin, Glazunov, Glinka, Lyadov, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Tchaikovsky, as well as other composers such as Grieg and Liszt. Outside of Russia, Rachmaninoff conducted almost exclusively his own works.

5. Personal Life

Rachmaninoff's personal life was marked by a reserved demeanor, deep family ties, and a strong connection to his Russian heritage, even in exile.

5.1. Marriage and Family

Rachmaninoff married his first cousin, Natalia Satina, on May 12, 1902. Their marriage was initially opposed by the Russian Orthodox Church due to their familial relation, requiring special permission from the Emperor, which was eventually secured through the efforts of his aunt. The ceremony was a small, private affair. The couple had two daughters, Irina Sergeyevna Rachmaninova (born May 14, 1903) and Tatiana Sergeyevna Rachmaninoff (born 1907). His family life remained a constant amidst his demanding career and periods of exile. After the Russian Revolution, he made efforts to support his family and friends who remained in Russia by sending money and food parcels.

5.2. Character and Hobbies

Rachmaninoff was generally perceived as a serious, reserved, and melancholic individual. His personality was deeply shaped by early life traumas, including his family's financial ruin, his parents' divorce, and the deaths of his sisters. The sudden death of his idol, Tchaikovsky, also cast a shadow over his character. The disastrous premiere of his First Symphony was a decisive blow, leading him to write to a friend that he "became a different person" after returning from Saint Petersburg. After leaving Russia, he became even more withdrawn, opening up only to a select few. Igor Stravinsky famously described him as "a six-and-a-half-foot scowl." However, he was also known to laugh heartily at Feodor Chaliapin's anecdotes.

The lilac flower became deeply associated with Rachmaninoff, symbolizing his romanticism, particularly due to his popular song "Lilacs" (Op. 21, No. 5). White lilacs were mysteriously delivered to his concerts and residences, even after his emigration, by an anonymous admirer who was later identified as Thekla Russo.

Despite composing major liturgical works like Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and All-Night Vigil, Rachmaninoff was not considered a devout Orthodox Christian. His creation of such grand religious pieces surprised his contemporaries. However, he inscribed "Completed, glory to God" on the manuscripts of Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom and Symphonic Dances.

Rachmaninoff was known for his stubbornness regarding the interpretation of his own works. He refused to slightly quicken the first movement of his Piano Concerto No. 2 when asked by conductor Fritz Reiner during a performance with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. When performing his Piano Concerto No. 3 with the Berlin Philharmonic, he even bypassed conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler to directly instruct the orchestra, leading to Furtwängler's angry Russian reprimand.

While he left statements on how to improve piano playing, he strongly disliked teaching piano, especially to "untalented students," believing it was a waste of his time. He also disliked child prodigies. However, he was supportive and humorous in his guidance of young musicians whose talent he recognized, such as Gina Bachauer and Ruth Slenczynska. He emphasized "practicing relentlessly" as the key to improving performance and understanding music.

He disliked radio broadcasts due to the poor sound quality of the time and his belief that he could not perform well without an audience in a confined room. He also stated that "a certain tension is necessary when listening to music, and the essence of music cannot be understood on the radio, where one can comfortably listen to music in a cozy room."

Rachmaninoff was known for his generosity. After achieving financial success as a pianist abroad, he readily provided financial support to struggling artists and organizations in Russia after the Revolution, including the Mariinsky Theatre choir and the Moscow Art Theatre. When the Soviet Union faced dire circumstances during the Nazi invasion, he organized charity concerts to support the Soviet war effort, personally delivering the proceeds to the Soviet consul in New York.

Despite his aristocratic background and choice to live abroad after the revolution, Rachmaninoff had shown anti-establishment tendencies even before 1917. In 1905, he signed a "Free Artist Declaration," which drew the attention of the Imperial Russian authorities. During an interview shortly after his emigration, he stated that "successive Russian emperors contributed nothing to the development of Russian music." He generally kept his distance from the political activities of other Russian émigré groups. There were even plans by Joseph Stalin in his later years to invite him back to Russia.

Rachmaninoff had a pet dog named Levko. He was also fascinated by cutting-edge technology, investing 5.00 K USD (approximately 100.00 K USD today) in the Sikorsky company, known for its helicopters. He loved automobiles and in 1912 bought an early gasoline-powered car (a Leigh Company model) for his wife. He enjoyed driving at high speeds, acquiring fast sports cars like Mercedes and Bugattis, despite the scarcity of cars in Russia at the time. After moving to the US, he hired a Russian chauffeur because he could not obtain a driver's license.

6. Reputation and Legacy

Rachmaninoff's reputation as a composer initially generated varied opinions before his music gained steady recognition worldwide.

6.1. Critical Assessment

The 1954 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians notoriously dismissed Rachmaninoff's music as "monotonous in texture... consist[ing] mainly of artificial and gushing tunes" and predicted that his popular success was "not likely to last." To this, Harold C. Schonberg, in his Lives of the Great Composers, responded: "It is one of the most outrageously snobbish and even stupid statements ever to be found in a work that is supposed to be an objective reference." Schonberg argued that what matters for a composer is how well they express their individuality, the strength of their ideas, and in these aspects, Rachmaninoff surpassed most composers. As Deryck Cooke noted, "Because of the enthusiastic support from performers and audiences, Puccini and Rachmaninoff continue to live in our musical experience despite the barrage of negative reviews." The prediction of the 1954 Grove Dictionary did not come true. The 1980 edition of The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians described his music's characteristics as "notable lyricism, breadth of expression, structural ingenuity, and a rich and distinctive orchestral palette." In recent years, works that were previously less performed have gained attention, and his enthusiastic fan base continues to grow.

In May 2014, Rachmaninoff's handwritten score for his Symphony No. 2, spanning 320 pages, was auctioned at Sotheby's in London for 1.20 M GBP.

6.2. Influence

Rachmaninoff's influence extends to subsequent generations of pianists and composers, and his lasting place in the classical music canon is secure. He is considered one of the most successful musicians in history, excelling as both a composer and a pianist, a feat often compared to Franz Liszt. His piano concertos, especially the Second and Third, are among the most frequently performed and recorded works in the repertoire. His unique compositional voice, blending Russian Romanticism with his distinctive melodic and harmonic language, continues to captivate audiences worldwide.

6.3. Memorials and Honors

The Conservatoire Rachmaninoff in Paris, as well as streets in Veliky Novgorod (close to his birthplace) and Tambov, are named after the composer. In 1986, the Moscow Conservatory dedicated a concert hall on its premises to Rachmaninoff, designating the 252-seat auditorium Rachmaninoff Hall. In 1999, the "Monument to Sergei Rachmaninoff" was installed in Moscow. A separate monument to Rachmaninoff was unveiled in Veliky Novgorod, near his birthplace, on June 14, 2009.

A statue marked "Rachmaninoff: The Last Concert," designed and sculpted by Victor Bokarev, stands at the World's Fair Park in Knoxville, Tennessee, as a tribute to the composer's final performance. In Alexandria, Virginia, in 2019, a Rachmaninoff concert performed by the Alexandria Symphony Orchestra played to wide acclaim. Attendees were treated to a talk prior to the performance by Rachmaninoff's great-granddaughter, Natalie Wanamaker Javier, who joined Rachmaninoff scholar Francis Crociata and Library of Congress music specialist Kate Rivers on a panel of discussants about the composer and his contributions.

The minor planet (4345) Rachmaninoff is named in his honor. The 2015 musical Preludes by Dave Malloy depicts Rachmaninoff's struggle with depression and writer's block.