1. Early Life and Education

Arthur Nikisch's formative years were marked by early musical talent and comprehensive training that laid the foundation for his illustrious career.

1.1. Birth and Family Background

Arthur Augustinus Adalbertus Nikisch was born on October 12, 1855, in Mosonszentmiklós, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary. His father was of German-Slavic descent and worked as a bookkeeper for a baronial family, while his mother, Luise von Lobotz, was Hungarian. The family later moved, and Nikisch grew up in Bussowitz, Moravia, speaking German rather than Hungarian.

Nikisch displayed exceptional musical talent from a very young age. He began learning piano and basic music theory from a school teacher at age five, making rapid progress. In the same year, he also started playing the violin. By age seven, he encountered an orchestrion, an automatic musical instrument, and was able to perfectly reproduce the overtures of Gioachino Rossini's The Barber of Seville and William Tell, and Giacomo Meyerbeer's Robert le diable on the piano after hearing them just once. At eight years old, he gave his first public piano performance, already capable of playing piano arrangements of operas by Sigismond Thalberg. Nikisch also began composing, creating sonatas, quartets, cantatas, and symphonies. Recognizing his son's extraordinary talent, Nikisch's father decided against formal schooling, opting instead for private tutors. This allowed Nikisch to acquire a deep general education and become fluent in several languages. Music critic Werner Ehrhardt noted that Nikisch's writings revealed an exceptional level of culture.

1.2. Vienna Conservatory

In 1866, at the age of eleven, Nikisch enrolled in the Vienna Conservatory, where he studied composition, piano, and violin. He proved to be an outstanding student, quickly advancing to the advanced composition class, which was typically reserved for graduates. By age thirteen, he had won numerous awards, including first prize in composition for a string sextet, first prize in violin, and second prize in piano. At sixteen, he performed a violin solo with the Vienna Court Orchestra as a substitute.

During his student years, Nikisch actively participated as a member of various orchestras. In 1872, upon the recommendation of his teacher Joseph Hellmesberger, Jr., he played Beethoven's Symphony No. 3 under the baton of Richard Wagner. A week later, he performed Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Bayreuth Festival Theatre. Nikisch later stated that Wagner's conducting of these symphonies profoundly influenced his understanding of Beethoven and his orchestral interpretations, noting that Wagner's movements themselves were "music." In 1873, as a second violinist in the Vienna Court Orchestra, he performed Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 2 under the composer's own direction. Nikisch recalled being immediately moved by the symphony, an emotion that persisted for decades. At eighteen, he made his conducting debut at the Conservatory's graduation concert, leading his own Symphony No. 1. Although recognized as a composer, he later ceased composing, believing there was no need to "build a roof upon a roof."

2. Career as a Violinist

On January 1, 1874, Nikisch became a first violinist at the Vienna Court Opera. He performed under the direction of notable composers such as Franz Liszt, Johannes Brahms, Giuseppe Verdi, and Anton Rubinstein. Concurrently, he was also a member of the Vienna Philharmonic and played in the Bayreuth Festival orchestra during its inaugural season in 1876. However, Nikisch found orchestral life tedious. Between 1875 and 1876, he had eight unauthorized absences, often hiring substitutes with his own money, particularly when Italian bel canto operas were performed. This often left him in financial straits.

His composition teacher and court Kapellmeister, Felix Otto Dessoff, noticed Nikisch's dissatisfaction. When Dessoff learned from Angelo Neumann, director of the Leipzig Opera, that a chorus conductor position was available, he informed Nikisch. This opportunity prompted Nikisch to leave Vienna and pursue a career as a conductor.

3. Conducting Career

Arthur Nikisch's conducting career was extensive and highly influential, marked by his leadership of major orchestras across Europe and North America.

3.1. Early Conducting in Leipzig

In 1878, Nikisch moved to Leipzig and began his conducting career as the chorus conductor at the Leipzig Opera. Within four weeks, he was promoted to Kapellmeister. His conducting debut on February 11, 1878, leading an operetta from memory, was a resounding success, described as "orchestra and stage came under a spell." A year later, at just 24, he became the orchestra's principal conductor. During his first rehearsal as principal conductor, the orchestra members initially resisted, feeling he was "too young" to lead Tannhäuser. However, after the director, Angelo Neumann, sent a telegram allowing them to disperse if they disliked Nikisch's rehearsal, the musicians were so impressed by his conducting that they performed the entire opera.

For ten years, Nikisch dedicated himself to the Leipzig Opera, staging new productions of older works while also introducing contemporary pieces such as Wagner's Ring Cycle and Tristan und Isolde. Composers like Ignaz Brüll, August Bungert, and Viktor Nessler also appeared as conductors during his tenure, with Nessler's Der Trompeter von Säckingen receiving particular acclaim. Under Nikisch's leadership, the Leipzig Opera rose to become one of Germany's top opera houses. During this period, other talented conductors also joined the Leipzig Opera, including Alexander von Fielitz (1886-1887) and Gustav Mahler, who became vice-Kapellmeister in 1886. While Nikisch and Mahler both captivated audiences and held mutual respect, they never became personally close. After Mahler left Leipzig two years later, Nikisch also began to feel that Leipzig was too small for his ambitions.

Nikisch also conducted concerts with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, which served as the opera orchestra. In 1880, he led Schumann's Symphony No. 4, earning high praise from Schumann's widow, Clara Schumann. In 1884, he conducted the world premiere of Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 with the Gewandhaus Orchestra, a performance that proved to be a major success.

3.2. Boston Symphony Orchestra

In 1889, Nikisch left Leipzig to become the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, invited by its founder, Henry Lee Higginson. The Boston Symphony was a highly regarded orchestra, supported by wealthy patrons. Nikisch received an annual salary of 10.00 K USD, considered a princely sum, and was provided with a luxurious salon car for his extensive tours. Despite these comforts, the stress of traveling nearly 186 K mile (300.00 K km) across the United States led him to resign after approximately four years. His departure was marked by farewell concerts in several cities. Music critic Takanobu Uechi noted that Nikisch's tenure added significant weight to the early history of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Among the musicians who played under Nikisch in Boston was Otakar Nováček.

3.3. Budapest Royal Opera

Nikisch returned to Europe in 1893 and assumed the role of Music Director at the Budapest Royal Opera. However, he found the political intrigues and power struggles distasteful and resigned before his term ended. He reportedly stated that he "hated feeling Hungarian" during this period. Nevertheless, he assisted musicians, such as helping harpist Alfred Kastner secure a position at the Royal Academy.

3.4. Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

In 1895, following the retirement of Carl Reinecke after 35 years, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra selected Nikisch as his successor. He was enthusiastically welcomed by the Leipzig public and remained "the most popular person in Leipzig" for the next quarter-century. His contract with Leipzig, like his concurrent position in Berlin, continued until his death.

Nikisch significantly expanded the Gewandhaus Orchestra's repertoire. While Reinecke's era focused on classical works and Schumann, Nikisch introduced contemporary composers such as Franz Liszt, Anton Bruckner, Johannes Brahms, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Richard Wagner, and Richard Strauss to Leipzig audiences. In 1896, he invited Brahms to attend his performance of Brahms's Symphony No. 4. From 1919 to 1920, he conducted a series of continuous Bruckner symphonies. Nikisch also organized "worker concerts" without a fee and, in 1918, conducted Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 for the "Festival of Freedom and Peace" to celebrate the end of World War I for Leipzig's laborers. His popularity in Leipzig was legendary; during an electrical workers' strike, when a rumor spread that Nikisch was suffering a heart attack and his life-saving equipment was non-functional due to the power outage, the strike was immediately called off.

3.5. Berlin Philharmonic

In 1895, after the retirement of its first principal conductor, Hans von Bülow, the Berlin Philharmonic appointed Nikisch as its principal conductor. This dual appointment with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra lasted until his death in 1922.

Nikisch's tenure with the Berlin Philharmonic is often referred to as the orchestra's "second golden age." However, his initial period in Berlin was challenging due to his limited recognition there. His Berlin debut concert on October 14, 1895, was not as successful as his Leipzig debut just four days prior, with the hall only half-filled despite the distribution of free tickets. Critics initially dismissed Nikisch as "pretentious" and "flashy" and deemed his Beethoven interpretations "substandard." Nevertheless, Nikisch gradually earned a strong reputation. In 1897, he was entrusted with a major tour to Germany, Switzerland, and France, which proved highly successful. In Paris, thousands flocked to his concerts. During one Parisian concert, in response to a recent fire that caused many deaths, Nikisch changed the program to Beethoven's Symphony No. 3, having the orchestra stand during the second movement's funeral march.

The success abroad sparked interest in Nikisch and the Berlin Philharmonic among Berliners, leading to sold-out standing-room tickets. This demand prompted the construction of a "glass-roofed hall" in 1898, followed by the acquisition of land for the "Beethovensaal," a hall with 1,036 seats, the following year. The orchestra's premises expanded to include the Stern Conservatory. Nikisch led further major tours in 1899, 1901, and 1904. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, foreign tours became impossible, although neutral Scandinavian countries remained open. A planned 1917 concert in Oslo was canceled due to anti-German protests. Despite the war, Nikisch considered himself an "international artist," believing his mission was to build bridges of understanding and friendship through art.

During Nikisch's time, the Berlin Philharmonic featured prominent soloists such as Mattia Battistini, Teresa Carreño, Fritz Kreisler, Elena Gerhardt, Pablo Casals, Heinrich Schlusnus, and Jascha Heifetz. Notable orchestra members included concertmasters Václav Talich and Louis Persinger, and cellist Joseph Malkin. In 1903, the orchestra members established the Berlin Philharmonic Limited Company.

3.6. London Symphony Orchestra

Nikisch began conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in 1905 and served as its Principal Conductor from 1912 to 1914. He highly regarded the orchestra's principal horn player, Adolf Borsdorf, sometimes dropping his baton in admiration of Borsdorf's beautiful playing during rehearsals. In April 1912, Nikisch led the London Symphony Orchestra on a pioneering tour to the United States, marking the first time a European orchestra had toured there. However, with the outbreak of World War I, he was classified as an enemy alien by the British and had to step down from his position with the London Symphony Orchestra, largely confining his activities to Germany during the war.

3.7. Guest Conducting

In addition to his long-standing positions in Leipzig and Berlin, Nikisch significantly expanded his sphere of influence through frequent guest conducting engagements. In 1897, he became the conductor of the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra, a position he held until his death. From 1905 to 1906, he also served as director of the Leipzig City Theater and the director of the Leipzig Conservatory, where he taught a conducting class. He was a popular guest conductor with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam. He notably conducted Richard Wagner's Ring Cycle at Covent Garden in London.

Nikisch's schedule was famously demanding. For example, in the spring of 1903, he conducted a court concert in Altenburg on Thursday, his final regular concert in Hamburg on Friday, a concert in Hanover on Saturday, then took a night train back to Berlin for a public dress rehearsal on Sunday, followed by the concert itself on Monday. On Monday night, he would travel by train to Saint Petersburg for three concerts, then continue to Moscow for an equal number of performances. In 1921, he conducted several concerts at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, with his son, pianist Mitja Nikisch, appearing as a soloist in some of these performances. Despite his extensive international career, Nikisch never conducted at the Bayreuth Festival, reportedly because conductors with international reputations were considered unsuitable for Bayreuth at the time. Beyond conducting, Nikisch occasionally performed as a pianist, accompanying singers.

4. Repertoire and Interpretations

Nikisch's musical preferences and interpretive approach were highly influential, particularly in his championing of contemporary composers and his distinctive readings of established masters.

4.1. Championing Contemporary Composers

Nikisch believed it was his duty to repeatedly program works by composers who were not yet widely recognized. He actively embraced late Romantic and contemporary music. He introduced works by composers such as Franz Liszt, Anton Bruckner, Johannes Brahms, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg, Claude Debussy, Kurt Atterberg, Hans Pfitzner, Max Reger, Hugo Wolf, Jean Sibelius, Edvard Grieg, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Antonín Dvořák, César Franck, Camille Saint-Saëns, Vincent d'Indy, Edward Elgar, Frederick Delius, Eugen d'Albert, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, Hugo Kaun, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Anatoly Lyadov, Moritz Moszkowski, Joachim Raff, Emil von Reznicek, Xaver Scharwenka, Max von Schillings, Georg Schumann, Christian Sinding, Josef Suk, George Szell, Hermann Unger, Robert Volkmann, Felix Weingartner, and Friedrich Gernsheim. He also conducted the premieres of works by Wilhelm Stenhammar, Anton Averkamp, Yuri Konyus, Rudolf Nováček, Ferdinand Pfohl, and Viktor Nessler. During his tenure with the Berlin Philharmonic, there was never a season without a premiere performance.

Nikisch also programmed works by older composers such as Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, and Louis Spohr. However, he rarely conducted works by Joseph Haydn or Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with only a "Mozart Evening" in 1906 to commemorate the composer's 150th birth anniversary. Herbert Haffner noted Nikisch's preference for "mixed programs," often combining works like Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto with Bruckner's Symphony No. 8, or Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 1 with Bruckner's Symphony No. 9. Paul Bekker stated that Nikisch became famous for his interpretations of Tchaikovsky and Bruckner.

4.1.1. Anton Bruckner

Deeply moved by Bruckner's Symphony No. 2 as a second violinist in 1873, Nikisch later became a prominent conductor of Bruckner's works, conducting numerous performances and world premieres. During his time as Kapellmeister at the Leipzig Opera, Nikisch was encouraged by Franz Schalk to include Bruckner's yet-unperformed Symphony No. 7 in his "Evenings of Contemporary Music." Nikisch became captivated by the work and, after corresponding with the composer, conducted its world premiere on December 30, 1884. The concert was a great success, and Bruckner bestowed two laurel wreaths upon him, calling Nikisch "one of God's deputies."

Nikisch gradually integrated Bruckner's works into the Berlin Philharmonic's programs, building audience support. He began on October 26, 1896, with the second movement of Symphony No. 7 as a tribute to Bruckner, who had died earlier that month. He then systematically introduced other symphonies: No. 5 (1898), No. 2 (1902), No. 9 (1903, 1904), No. 3 (1905), No. 8 (1906), and No. 4 (1907), thereby establishing Bruckner's works as a regular part of the orchestra's repertoire. This gradual approach was a deliberate strategy by Nikisch, as Bruckner's music was often misunderstood by both audiences and critics at the time.

4.1.2. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Nikisch actively conducted works by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Unlike his gradual introduction of Bruckner's music, Tchaikovsky's compositions were a regular feature in his programs. His Symphonies No. 4, No. 5, and No. 6, as well as the Piano Concerto No. 1 and the Violin Concerto, frequently appeared in his concerts. Tchaikovsky himself was deeply grateful to Nikisch for the success of his Symphony No. 5, which had been poorly received at its own premiere. Tchaikovsky reportedly told Nikisch that he had intended to burn the score if it was rejected again, and embraced him amidst the audience's applause. Initially, the orchestra had refused to perform the symphony, but Nikisch reportedly insisted, threatening to cancel his guest appearance if the work was not included.

4.1.3. Richard Strauss

Nikisch held Richard Strauss's works in high regard, programming them from his very first season with the Berlin Philharmonic. He conducted major orchestral works such as Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Also sprach Zarathustra, Ein Heldenleben, Sinfonia Domestica, Festliches Präludium, and An Alpine Symphony four or more times each.

4.1.4. Gustav Mahler

Despite a somewhat strained relationship with Gustav Mahler during their time together at the Leipzig Opera, Nikisch frequently conducted Mahler's compositions. On November 9, 1896, he conducted the premiere of the second movement of Mahler's Symphony No. 3 with the Berlin Philharmonic, also performing it in Leipzig. In Berlin, he conducted Mahler's Symphonies No. 5, No. 2, No. 4, and No. 1, as well as Kindertotenlieder and Das Lied von der Erde. In 1907, Mahler himself conducted his complete Symphony No. 3 with the Berlin Philharmonic. However, most of Mahler's larger works were conducted only once by Nikisch, leading music critic Werner Ehrhardt to suggest that Nikisch maintained a certain distance from Mahler's music.

4.2. Interpretations of Beethoven and Liszt

Nikisch was considered an outstanding interpreter of the music of Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Liszt. His interpretations were marked by a willingness to adjust tempos for acoustic effect, and he frequently employed string portamento and fermata. He also made occasional score modifications and even altered the performance order of movements or overtures, such as swapping the order of Beethoven's Leonore Overture No. 2 and Leonore Overture No. 3. Werner Ehrhardt noted that Nikisch's sound production was fundamentally based on the strings, due to his own skill as a violinist, with the colors of other instruments layered upon this rich string "canvas."

5. Conducting Style and Philosophy

Arthur Nikisch's unique approach to conducting, characterized by his distinctive techniques and underlying musical philosophy, set him apart as a visionary leader on the podium.

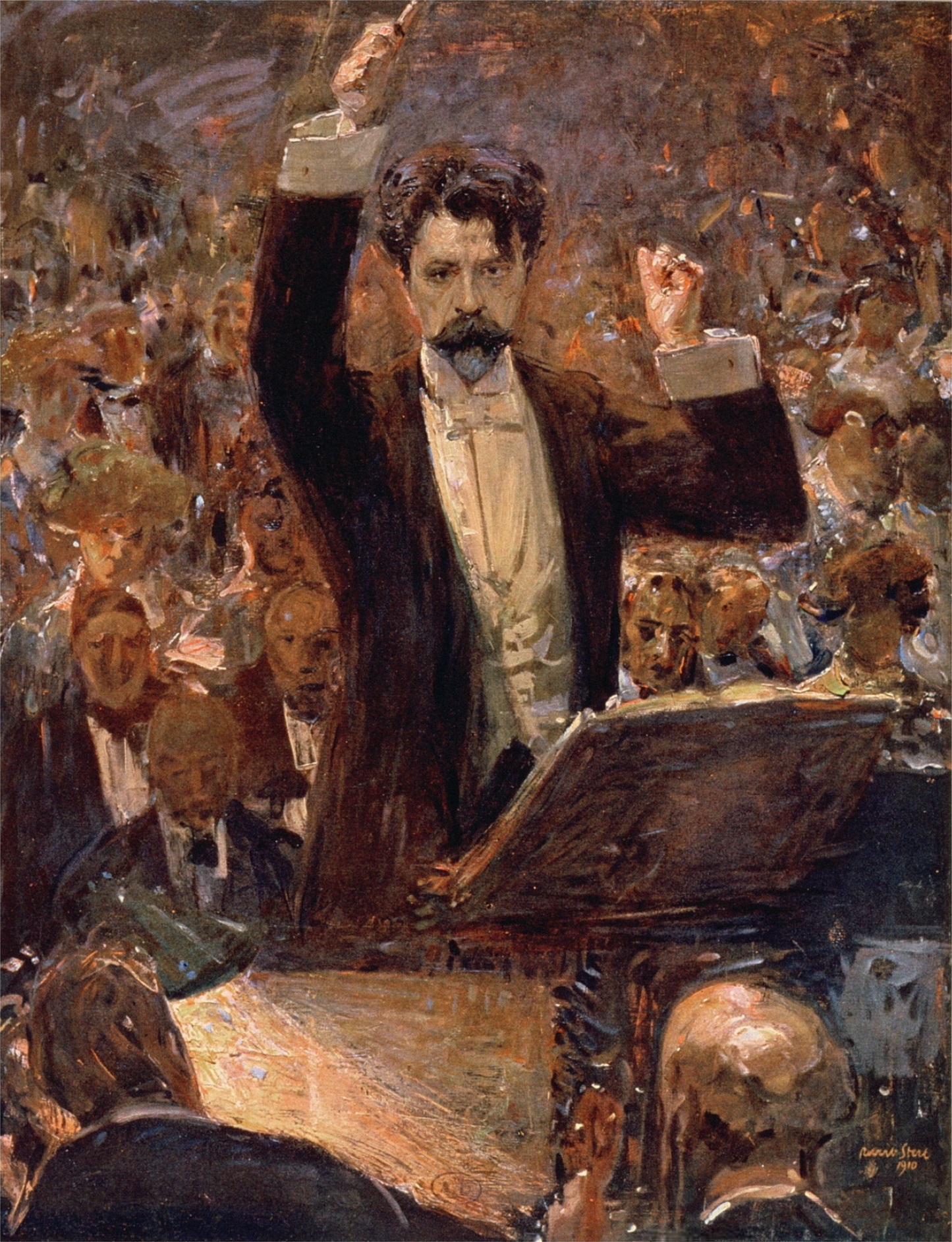

5.1. Minimalist and Charismatic Technique

Nikisch's conducting style was remarkably restrained. He held a long baton in his right hand, moving only its tip with a flick of his wrist, while his left hand subtly emphasized musical points. He was renowned for his expressive use of his eyes, which allowed him to guide the orchestra through difficult passages and communicate his intentions with minimal physical movement. Conductor Fritz Reiner famously quoted Nikisch as saying, "You should never wave your arms in conducting, and that you should use your eyes to give cues."

This minimalist technique allowed Nikisch to elicit an ideal sound from his orchestras. Musicians often testified that they produced the sound Nikisch desired without fully understanding how he achieved it. Conductor Sir Adrian Boult remarked that if Nikisch indicated a legato, it was impossible for a skilled musician to play staccato. Boult also observed that Nikisch consistently achieved his results with the simplest movements, creating immense beauty with very little effort, and that his extensive experience as an orchestral musician allowed him to accomplish feats that seemed impossible to most. The "magic" of his conducting was so profound that Nikisch himself admitted he didn't fully understand how he conveyed his feelings to the musicians, stating he was "carried away by the stimulating power of music" and that his interpretations constantly varied in detail according to the intensity of his emotions. Conductor Eugene Ormandy noted that Nikisch "never repeated the same performance." Nikisch believed that all conductors should learn the violin to develop flexible wrist movements. He also famously conducted from memory, a rare practice at the time that astonished both audiences and his colleagues.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky described Nikisch's conducting as the antithesis of Hans von Bülow's dramatic and visually stimulating style. Tchaikovsky noted that Nikisch was "quiet, restrained in unnecessary movements, but resolute, powerful, and always self-controlled." He added that Nikisch "does not conduct; he surrenders himself to some ineffable, mysterious magic. The audience hardly pays attention to him, nor does he try to draw their attention to himself. Nevertheless, the entire orchestra, in the hands of this strange master, becomes a single instrument, following his direction completely and as if hypnotized." Conversely, Richard Strauss reportedly described Nikisch's hand movements as "vigorous." Conductor Igor Markevitch observed that modern conductors require "far more flexible and far more extensive technique" than Nikisch or Arturo Toscanini due to the expanded orchestral forces used by composers.

Nikisch often emphasized that "the most important duty of a conductor is to create an atmosphere." He believed that even a superb performance of a symphony was incomplete if the conductor failed to create an expectant atmosphere for the next movement during pauses. He frequently recounted an anecdote where an audience member asked a friend, "Tell me when the magic begins," highlighting the captivating aura he created.

5.2. The Conductor's Role

Nikisch believed that the conductor's primary duty was not merely to act as a substitute for the composer, but to elevate the conductor's role to be on par with that of the composer. In rehearsals, he would first play through the entire piece, then focus on problematic sections, repeating them as needed. However, he avoided giving overly detailed instructions, preferring to allow individual musicians freedom in their interpretations. Nikisch valued the intuition that arose during performance, and this approach earned him the trust of his musicians, with no instances of uncooperative behavior reported in his rehearsals. He made an effort to remember the names of his musicians, often greeting those he recognized from his own time as a violinist. Nikisch famously stated, "If an orchestra works diligently, outstanding skill will develop from it. Every musician has their own individuality, their own thoughts. There is no need to know them personally to elicit the correct sound. Like any other profession, in music, the instrument makes the person. The conductor must, so to speak, put the entire orchestra on the tip of their tongue and produce a sound entirely different from the musicians' instruments. Only then does the conductor achieve their goal. Individual players perform as they wish, but the trick of conducting is to make them think, 'Well, I suppose I'll listen to the conductor for once.'"

Conductor Fritz Busch, who observed Nikisch's rehearsals, recounted his charming greetings and how he captivated the entire orchestra before even beginning. Nikisch would often tell guest orchestras that it had been his long-standing dream to conduct them, a line he delivered with natural affability. Busch recalled an instance where Nikisch, seemingly moved, extended his arm to an elderly viola player, exclaiming, "Mr. Scherz, to see you here! Do you still remember when we performed the Mountain Symphony in Magdeburg under Liszt?" Busch noted that remembering musicians' names was another of Nikisch's inimitable talents, and that he won over the entire orchestra before even starting to conduct.

Due to his exceptional memory and ability to grasp things instantly, Nikisch sometimes encountered a score for the first time during a rehearsal. Music critic Werner Ehrhardt described how Nikisch could immediately perceive the full scope of a piece and meticulously envision its nuances in his mind, without prior preparation. He believed that for Nikisch, music was sound, and sound was a medium of a vibrating world, rich in infinite colors, brightness, intensity, and nuance. There is an anecdote that when Max Reger was concerned Nikisch might not know his new work, Reger asked him to rehearse the final fugue first. Nikisch replied, "Where is that?" as the piece had no final fugue.

6. Recordings and Pioneering Activities

Arthur Nikisch made significant contributions to the early history of orchestral recording and played a pioneering role in international orchestral touring.

6.1. Early Recording Pioneer

On November 10, 1913, Nikisch conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in one of the earliest recordings of a complete symphony, Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. This landmark performance, despite some cuts or reductions due to the technical limitations of early recording technology, was the first complete symphony recorded with the instrumentation indicated in the score and the first recording for the Berlin Philharmonic. It was later reissued on LP and CD by Deutsche Grammophon and other labels. While some critics, including Arturo Toscanini, felt the recording did not fully capture Nikisch's artistry, others, like Tadashi Koishi, noted its historical value and the "surprisingly dignified performance" that hinted at why Toscanini so admired Nikisch.

Nikisch also made a series of early recordings with the London Symphony Orchestra, some of which feature the portamento characteristic of early 20th-century playing. These include the overtures to Beethoven's Egmont and Weber's Oberon (June 25, 1913), Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 1 (June 25, 1913, or June 21, 1914), Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro overture, and Weber's Der Freischütz overture (both June 21, 1914), all released by British Gramophone. In 1920, he recorded Berlioz's Roman Carnival Overture and Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 1 with the Berlin Philharmonic for Deutsche Grammophon. Koishi found the Liszt recording particularly interesting for its "Hungarian expression." Sam H. Shirakawa stated that Nikisch's recordings with the Berlin Philharmonic are more valuable as historical artifacts than as benchmarks of interpretive skill. A silent film of Nikisch conducting Tchaikovsky's Symphony was also made in 1920.

6.2. International Tours

Nikisch was a pioneer in international orchestral touring. In April 1912, he led the London Symphony Orchestra on a tour to the United States, marking the first time a European orchestra had undertaken such a tour. This pioneering effort opened new avenues for international musical exchange.

7. Personal Life

Arthur Nikisch's personal life was characterized by a captivating personality, a distinct public image, and a close family.

7.1. Marriage and Family

On July 1, 1885, Arthur Nikisch married Amélie Heussner (1862-1938), a Belgian soprano, singer, and actress who had previously performed with Gustav Mahler at the Kassel court theatre. Their son, Mitja Nikisch (1899-1936), became a noted pianist in his own right, often appearing as a soloist with the Berlin Philharmonic under his father's direction. While Mitja also pursued a career as a classical pianist, he gained more fame as a jazz band conductor. However, with the rise of the Nazis, jazz was condemned as "degenerate music," leading to the dissolution of his band. Mitja suffered from depression as a result and tragically committed suicide in Venice. Nikisch's daughter-in-law, Grete Merrem-Nikisch, also achieved recognition as a soprano.

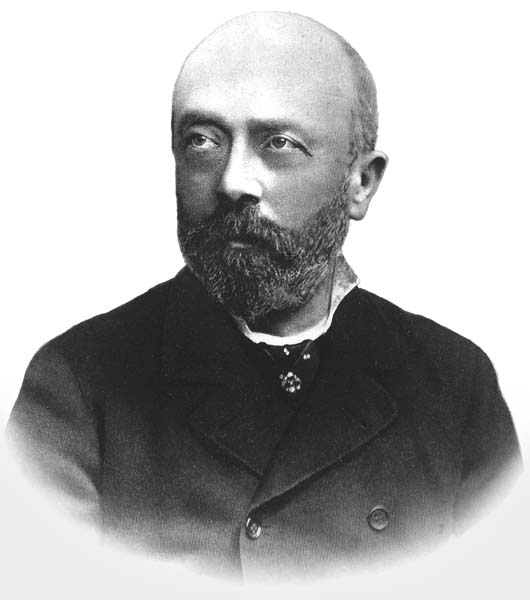

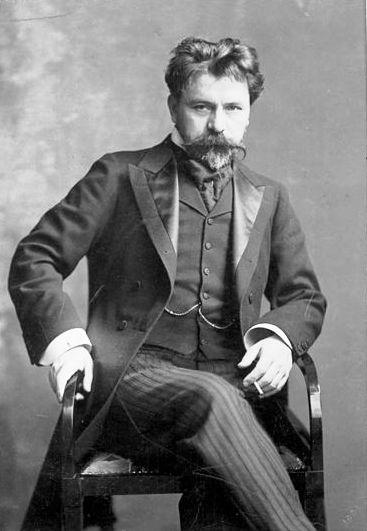

7.2. Personality and Appearance

Nikisch was known for his striking appearance and charismatic personality. He had blue eyes and black, curly hair, often complemented by a well-groomed beard. He dressed luxuriously, favoring fur coats, gold chain watches, kid leather gloves, and diamond rings. Even his ivory conducting baton was elaborately decorated. His biographer, Ferdinand Pfohl, described Nikisch as aristocratic in his speech, walk, and attire, presenting himself as a "gentleman" in both private and public settings. Werner Ehrhardt noted his "calm and graceful" demeanor, and his "natural elegance" that captivated people, contrasting him with the more intense Hans von Bülow.

Nikisch was immensely popular with women, with conductor Pierre Monteux remarking that he was famous for captivating female hearts across Europe and America. He was equally beloved by his audiences. At a concert celebrating his 25th anniversary as conductor in Berlin, when Nikisch asked the audience, "Do you still need me?", they responded with a resounding "As long as you live!" His popularity even extended beyond borders; a Russian officer held in a German prisoner-of-war camp during World War I reportedly asked his guards, "How is Nikisch doing?"

Despite his magical public image, Nikisch was said to enjoy a free-spirited lifestyle. He frequently played poker late into the night, sometimes gambling away his entire earnings. Eva Weissweiler noted that he preferred playing cards to reading. He also often visited the spa town of Bad Ischl, a popular gathering place for notable figures. On one occasion, after hearing Brahms's Clarinet Quintet performed by Richard Mühlfeld and the Kneisel Quartet in Brahms's presence, Nikisch was so moved that he knelt before the composer. Nikisch was generally robust, canceling Berlin concerts due to illness only twice, one of which was on the day of his death.

8. Death

Arthur Nikisch died in Leipzig on January 23, 1922, of a heart attack, while preparing for a concert. He was buried there. Immediately after his death, the square where he had lived was renamed Nikischplatz in his honor. In 1971, the city of Leipzig established the Arthur Nikisch Prize for young conductors as a further tribute.

His passing was widely mourned. Wolfgang Stresemann, then a gymnasium student, recalled that everyone felt Nikisch's death left an irreplaceable void in Berlin's musical life. Newspapers lamented the loss, with the Berliner Tageblatt stating, "This loss is irreparable... We still needed him..." and the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung remarking, "Looking across all our conductors, there is truly no one with such international authority and universality..." The Vossische Zeitung expressed, "We have no idea who could replace this master," and Gerhart Hauptmann hailed Nikisch as "a miracle in the musical world." Half-mast flags were displayed at the entrances of all major halls where Nikisch had performed.

Alongside the obituaries, newspapers speculated on his successor, mentioning names like Richard Strauss, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer, Felix Weingartner, and Siegmund von Hausegger. Ultimately, Furtwängler succeeded Nikisch in both Berlin and Leipzig.

9. Legacy and Influence

Arthur Nikisch's enduring impact on the field of conducting and the broader classical music world is profound, establishing foundational principles and inspiring generations of musicians.

9.1. Foundation of Modern Conducting

Nikisch is widely regarded as one of the founders of modern orchestral conducting. Alongside Hans von Bülow, he established essential elements of conducting, including thorough score analysis and a restrained conducting technique. Unlike Bülow, Nikisch actively championed and introduced works by Eastern European and Russian composers such as Bruckner and Tchaikovsky. His legacy is defined by his deep analysis of the musical score, his simple and controlled beat, and a charisma that allowed him to draw the full sonority from the orchestra and plumb the depths of the music. He was also a pioneer in early recording activities, making him one of the earliest conductors whose performances can still be heard today.

9.2. Influence on Successor Conductors

Nikisch's conducting style was greatly admired by many prominent conductors who followed him. Leopold Stokowski described Nikisch as a "truly great conductor." Arturo Toscanini, known for his critical nature, declared Nikisch to be a conductor who deserved an "unconditional 'excellent.'" While Toscanini initially called Nikisch a "dilettante" to violinist Nathan Milstein, he later told Milstein that Nikisch was "a great conductor! A master conductor!"

Conductors like Sir Adrian Boult, Fritz Reiner, Ervin Nyiregyházi, and George Szell (who called Nikisch "an orchestral wizard") were deeply influenced by him. Reiner recounted that Nikisch advised him, "You should never wave your arms in conducting, and that you should use your eyes to give cues." Henry Wood remembered Nikisch's "marvellous way of listening so intently to every phrase he directed," and how he would sing melodies to the orchestra with great emotional feeling, then tell them, "Now play it as you feel it." Wood believed no conductor surpassed Nikisch's emotional feeling and dramatic intensity.

Nikisch had a particularly profound impact on Wilhelm Furtwängler, who consistently considered Nikisch his sole model and expressed a desire to succeed him. Furtwängler praised Nikisch for his ability to "make the orchestra sing," a rare talent. Hans Knappertsbusch also held Nikisch in high regard, and Otto Klemperer was noted to be influenced by him. Igor Markevitch even referred to Nikisch's performances when revising Beethoven's symphonies.

Conductors who never met Nikisch, or were born after his death, also expressed admiration. Leonard Bernstein referred to Nikisch as his "musical grandfather." Herbert von Karajan was so impressed by a surviving film of Nikisch conducting that he reportedly said he would "pay a large sum" or "sacrifice his right arm" to see him conduct. Colin Davis, a student of Adrian Boult (who was Nikisch's student), was inspired by Nikisch's wrist-only conducting with a long baton. Herbert Blomstedt associated the "German sound" with Nikisch, Furtwängler, Busch, and Kleiber.

Nikisch's name is often invoked when praising conductors. In 1924, the Krasnaya Gazeta newspaper lauded Otto Klemperer as a "great conductor of his time," comparing him to Nikisch and Mahler. Joanna Fiedler described Valery Gergiev as possessing a "charismatic quality that cannot be expressed in words," a trait shared by many great conductors dating back to Nikisch and Toscanini. Conversely, critics also used Nikisch as a benchmark for criticism; James Huneker suggested that Toscanini did not always reach the peak achieved by Anton Seidl or Nikisch.

9.3. Accolades from Composers and Musicians

Nikisch's conducting philosophy, which aimed to elevate the conductor's role to be on par with the composer's, earned him widespread acclaim from composers. Johannes Brahms, after hearing Nikisch conduct his symphony, told him, "Your way is completely different from my ideas. But your way is correct, it must be so!" Richard Strauss noted Nikisch's "ability to draw sounds we could not even imagine."

Nikisch's dedication to promoting unrecognized composers also garnered their praise. Anton Bruckner hailed Nikisch as "one of God's deputies" after the successful world premiere of his Symphony No. 7. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, whose Symphony No. 5 had been poorly received at its own premiere, embraced Nikisch amidst applause after Nikisch conducted a highly successful performance, telling him he had intended to burn the score if it was rejected again. Even the notoriously critical composer Arnold Schoenberg was reportedly satisfied with Nikisch's conducting. Franz Liszt, after a concert in 1885, called Nikisch "a master among masters." Sergei Rachmaninoff considered Nikisch his most highly regarded conductor, particularly praising his interpretation of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5. However, Nikolai Medtner criticized Nikisch's "melancholy slow tempo" in the fourth movement of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5, arguing that it became the standard for Tchaikovsky's performances, even if it saved the work from complete failure.

Musicians who played under Nikisch also offered high praise. Chorus conductor Siegfried Ochs, who performed in Nikisch's orchestra, noted that Nikisch led musicians with "almost invisible movements," sometimes with seemingly incomprehensible gestures, yet the musicians always played as he wished, even if they didn't understand how. Members of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra also lauded Nikisch, with Hugo Burghauser describing how Nikisch seemed to emit a magnetic force from his "supple, pale hands," creating a magical aura around him. Even Carl Flesch, a violinist known for his disdain for conductors, acknowledged Nikisch as a rare conductor who could convey the "fundamental force" of rhythm, dynamics, and the hidden emotions behind the notes, stating that "a new era of conducting began with Nikisch." Pianist Claudio Arrau cited Nikisch, with whom he performed as a boy, as an influential figure in his artistic development.

Music critics also recognized Nikisch's unique impact. Julius Korngold, who attended Nikisch's concerts, described how the hall would turn "blood red" at dynamic climaxes, and sometimes the lights seemed to suddenly brighten. While early critics in Berlin initially dismissed him, they gradually became his supporters. Sam H. Shirakawa called Nikisch the "prototype of the modern superstar conductor." Rupert Streh observed that with Nikisch, the conductor, rather than the musical work, became the focus of audience interest, possessing a "mysterious aura" that captivated thousands, much like Niccolò Paganini and Liszt. Christian Merlan noted that Nikisch, along with Bülow and Mahler, belonged to the first generation of conductors who transformed into "maestro assoluto," living gods, becoming mythical figures and objects of almost religious worship.

However, some critics also offered critiques. Journalist Herbert Haffner suggested that Nikisch lacked Bülow's strict rationality, active engagement with musical problems, and educational mission. Haffner also noted that, like his successor Furtwängler, Nikisch became more conservative over time, eventually being overtaken by the currents of modernity. Werner Ehrhardt pointed out that Nikisch remained an artist of the "fin-de-siècle," showing little interest in the avant-garde musical movements of the early 20th century that challenged the traditional musical world.

10. Memorials and Honors

In addition to the renaming of the square where he lived to Nikischplatz and the establishment of the Arthur Nikisch Prize for young conductors by the city of Leipzig, the Leipzig City Council created the "Nikisch Memorial Ring" in his honor. This prestigious award, which Franz Endler compared to the "Iffland Ring" in the acting world, has been bestowed upon notable conductors such as Yevgeny Mravinsky, Franz Konwitschny, Karl Böhm, and Kurt Masur.