1. Overview

Saburō Sakai, born 坂井 三郎Sakai SaburōJapanese on August 25, 1916, was a distinguished Imperial Japanese Navy fighter pilot and flying ace during World War II. Officially credited with 28 aerial victories, a figure contested by his autobiography Samurai! and its ghostwriter Martin Caidin who claimed much higher numbers, Sakai became one of Japan's most famous surviving aces. His military career spanned the Second Sino-Japanese War and the entirety of the Pacific War, where he was renowned for his exceptional piloting skills, observational abilities, and tactical prowess, even after sustaining a severe head injury over Guadalcanal.

Following the war, Sakai transitioned to civilian life, eventually establishing a printing business. He gained international recognition through his widely translated autobiography, Samurai!, though the book has been subject to considerable controversy regarding its factual accuracy and the role of ghostwriters. His post-war public life was also marked by his involvement in a controversial pyramid scheme, as well as his candid and often critical reflections on wartime Japanese military leadership, the nature of conflict, and the responsibility for Japan's post-war societal trajectory. Despite the controversies, Sakai engaged in reconciliation efforts with former adversaries and continued to influence popular culture through various media, remaining a significant, albeit debated, figure in military history until his death in 2000.

2. Early Life and Background

Saburō Sakai's formative years were shaped by humble beginnings and personal hardship, which ultimately led him to a distinguished career in naval aviation.

2.1. Birth and Childhood

Saburō Sakai was born on August 25, 1916, in Saga Prefecture, Nishiyoka Village, Saga County, Japan (present-day Saga City's Nishiyoka-machi Rin-gai). His given name, literally meaning "third son," derived from his grandfather Katsusaburō. He was the second son of Hide and Haruichi Sakai, a farmer, and was one of seven children, having three older brothers and three sisters. His family had a historical affiliation with the samurai class, with ancestors who participated in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592-1598), but after the abolition of the han system in 1871, they were compelled to take up farming. When Sakai was five, his family left his grandfather's home in what was described as a nocturnal escape, leading to a life of poverty. His father, Haruichi, worked at a small rice mill, but passed away from illness at the age of 36 in the autumn of 1928, when Sakai was 11. This left his mother to raise six children in difficult circumstances.

Recognizing Sakai's academic promise and their dire situation, his maternal uncle, a transportation ministry official in Tokyo, took him in to finance his education. Sakai attended Aoyama Gakuin Junior High School in Tokyo, an institution founded by American missionaries. However, he struggled academically and was eventually expelled after his second year due to poor grades and unsatisfactory conduct, leading him to return to Saga. For approximately two years, he engaged in farm work back home, during which he began to seriously contemplate his future. He harbored a desire for speed and initially considered becoming a jockey, but this path was opposed by his main family. Inspired by seeing a seaplane piloted by Gorō Hirayama, a naval captain from his village who flew with the Sasebo Air Group, perform low-altitude maneuvers over his hometown, Sakai developed an admiration for aircraft as "fast objects." He attempted to join the Naval Aviation Cadet program twice but was unsuccessful.

2.2. Enlistment and Pilot Training

Despite initial setbacks, Sakai remained determined to pursue a career in the navy, aspiring to be close to airplanes even if he could only observe or touch them. On May 1, 1933, at the age of 16, he successfully passed the enlistment examination for the Imperial Japanese Navy and joined the Sasebo Marine Barracks as a Sailor Fourth Class (Seaman Recruit).

His early experiences as a naval recruit were extremely harsh, characterized by brutal discipline from petty officers. Sakai recounted being beaten with a large wooden stick for any breach of discipline or training error, often to the point of unconsciousness, only to be revived with cold water and forced to continue. He described counting up to 40 impacts on his buttocks during these punishments. In October 1933, he was assigned to the battleship Kirishima as a 15-centimeter secondary gunner. In May 1935, he successfully passed the competitive examinations for the Naval Gunners' School in Yokosuka. Graduating second in his class of 200 the following year, he was assigned to the battleship Haruna in May 1936, serving as a gunner in one of its main turrets.

During this period, despite the era of "big-gun battleships" being in its prime, Sakai's true ambition remained aviation. After witnessing the launch of an aircraft from the Haruna, he confided in a superior officer about his desire to become an aviator. He was advised that passing the academic examination was crucial. Although his role as a main gunner was prestigious, his aspiration led to his transfer to a strenuous position as an ammunition handler in the ship's hold. Undeterred, he took the pilot training examination, which was his last chance given his age, and passed.

On March 10, 1937, Sakai entered the Kasumigaura Air Group. He made his first flight on April 1. Despite not initially being a naturally skilled pilot (he was among the last in his class to be allowed solo flight), he diligently studied and trained. He was eventually selected to become a carrier-based fighter pilot, graduating first in his 38th class of pilot trainees on November 30, 1937. At his graduation ceremony, he received an honorary silver watch from Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu, representing Emperor Hirohito. Although he qualified as a carrier pilot, he was never assigned to an aircraft carrier. One of his classmates was Jūzō Mori, who later served on the Japanese aircraft carrier Sōryū flying Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers. After graduating, he received extended training as a fighter pilot at the Saiki Air Group, where he honed his skills through rigorous combat training with seniors like Kaname Harada. On April 9, 1938, he was assigned to the Ōmura Air Group. On May 11, he was promoted to Petty Officer Third Class. He was then assigned to the Takao Naval Air Group.

3. Military Career

Saburō Sakai's military career was characterized by extensive combat experience across the Pacific, marked by significant aerial victories, a severe injury, and controversial claims regarding his achievements and later war activities.

3.1. Sino-Japanese War Service

In September 1938, Sakai was assigned to the 12th Air Group, advancing to its station in Jiujiang, China. On October 5, 1938, he participated in the Hankou air raid, flying a Mitsubishi A5M Type 96 fighter as the third aircraft in Commander Takanori Aio's formation. This marked his first combat mission, during which he shot down one Polikarpov I-16 fighter from the Republic of China Air Force.

Promoted to Petty Officer Second Class in May 1939, he took part in operations from Jiujiang against Nanchang. In June, he advanced to the captured Nanchang base. On October 3, Hankou base was attacked by 12 Tupolev SB bombers. Sakai scrambled and single-handedly pursued one bomber for 26 K ft (8.00 K m) above Yichang, shooting it down. In November, he moved to the Shanghai base, and in May 1940, to Yuncheng, engaging in patrols.

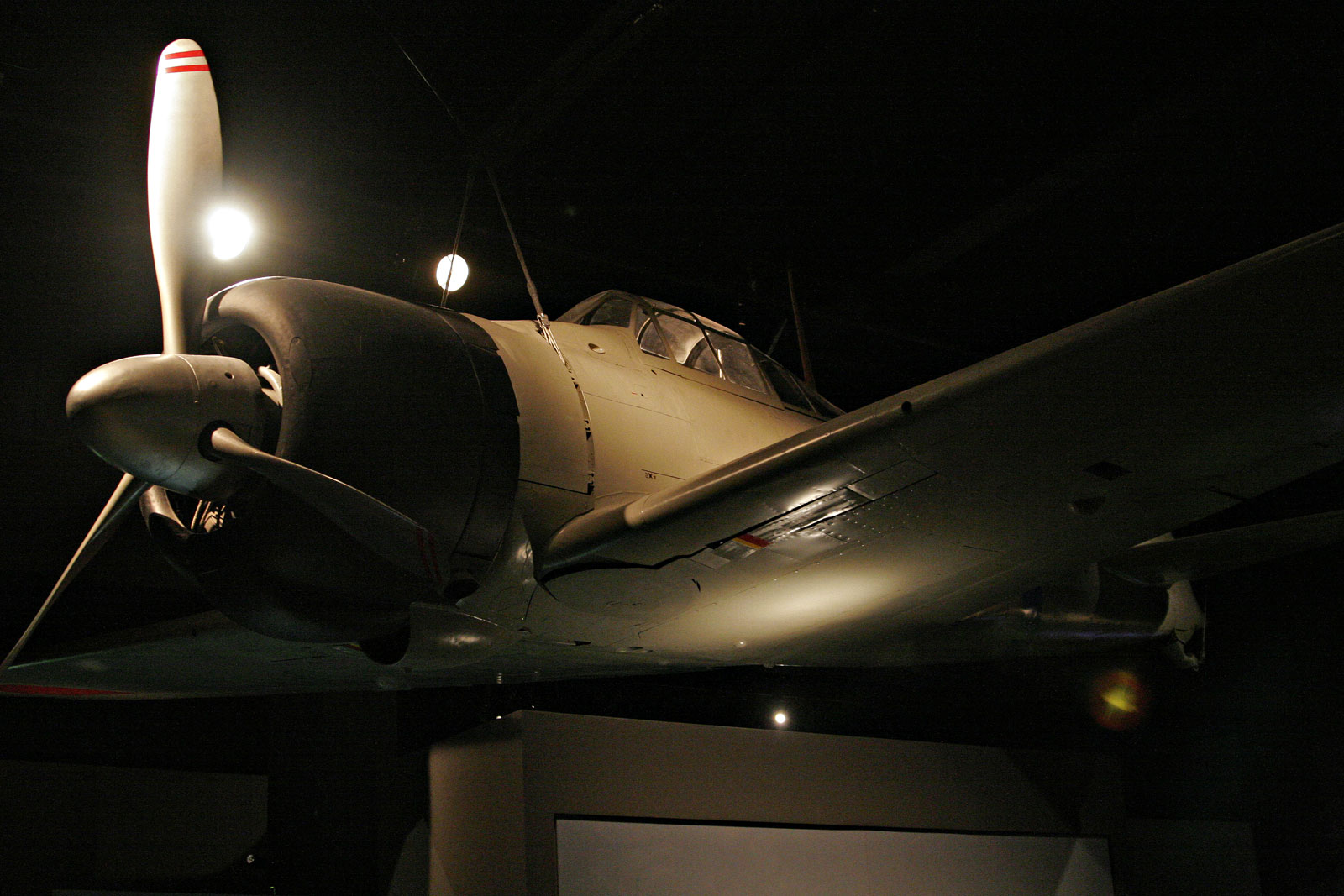

In June 1940, Sakai returned to Japan, assigned to the Ōmura Air Group. In August, at a new aircraft handling seminar at the Yokosuka Naval Air Group, he first saw the newly introduced Mitsubishi A6M Zero. On October 17, 1940, he was assigned to the Takao Naval Air Group. His aircraft changed from the Type 96 to the Zero. He ferried a Zero from Nagoya Airport via Kanoya Air Field to the Takao base, arriving on October 24. Sakai highly praised the Zero's maneuverability and its long range, which allowed pilots to focus on aerial combat without worrying about fuel. He was critical of the Zero Model 32, which had reduced wingspan for speed, considering it a degradation in terms of maneuverability.

In spring 1941, Sakai, as part of 18 Zeros from the Takao Air Group, advanced to the Sanya Base on Hainan Island. Then, 12 Zeros, including Sakai's, moved to Hanoi Airfield in response to the Japanese advance into northern French Indochina.

On April 10, 1941, Sakai was reassigned to the 12th Air Group, at the request of Captain Tamotsu Yokoyama, for renewed deployment to mainland China. From Hankou Base, he engaged in operations over Central China. On May 3, he participated in an attack on Chongqing. Promoted to Petty Officer First Class on June 1, he continued his activities in China, participating in attacks on Liangshan on July 9 and Chengdu on July 27. On August 11, he joined the Chengdu Dawn Raid, involving 16 Zeros and 7 Mitsubishi G3M land attack aircraft. Fighters moved to Yichang Airfield the day before and took off at night to rendezvous with the land attack aircraft from Hankou. During this mission, Sakai shot down one Polikarpov I-15 fighter of the Chinese Air Force, marking his first kill with the Zero. On August 21, during another Chengdu attack, he shot down another Polikarpov I-16. He then moved to Yuncheng Base as part of 18 Zeros dispatched to cut off the Soviet aid route (Northern Route). On August 25, he participated in an attack on Lanzhou Base with 7 Zeros, securing air superiority. A few days later, he joined an attack on Xining with 12 Zeros. On August 31, he participated in an attack on the Songpan Base in the Min Mountains, a difficult target due to its terrain, with 4 Zeros under Commander Hidenori Shingo. The mission was aborted due to bad weather. Sakai later recalled that he only had a few actual combat engagements during the Sino-Japanese War.

3.2. World War II Service

Saburō Sakai's service during World War II encompassed intense aerial combat across Southeast Asia, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, culminating in a severe injury and a return to the front lines amidst Japan's declining fortunes.

3.2.1. Southeast Asia and Dutch East Indies Campaigns

In October 1941, Sakai was assigned to the newly established Tainan Air Group at Tainan Airport in Taiwan, becoming a senior NCO pilot. He was reportedly the only NCO leading a flight, though other similar NCO-only flights existed within the unit. Sakai stated that he was asked by Commander Yasuna Kozono to provide combat training to newly assigned superior officer, Lieutenant Junichi Sasai. Sakai was also involved in disciplinary incidents, reportedly stealing chickens and pigs from local residents, which led to a reprimand from Kozono. He also admitted to smoking "Kanaka tobacco" (containing opium) and sharing it with other NCOs and enlisted men, defying Sasai's warnings and criticizing the superior tobacco ration given to officers.

On December 8, 1941, with the outbreak of the Pacific War, the Tainan Air Group participated in the attack on Clark Air Base in the Philippines. As flight leader of the third flight (Sakai, Yoko Kawano, Honda) of the First Squadron (commanded by Captain Hidenori Shingo), Sakai took off from Tainan Base. Protecting 27 Mitsubishi G4M bombers from the Takao Naval Air Group and 27 Mitsubishi G3M bombers from the 1st Air Group, Sakai engaged a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk from the US Army's 21st Pursuit Squadron over the smoking airfield at 1640 ft (500 m) altitude. He severely damaged the P-40 with a sharp left turn, a favored Zero maneuver, forcing it to crash-land. In May 1991, he met with Lieutenant Sam Gracio in Texas, and their recollections of the engagement matched. Sakai also claimed to have destroyed two B-17 Flying Fortresses by strafing them on the ground. He flew missions the next day during heavy weather.

On December 10, 1941, Japan claimed its first shootdown of a B-17. Sakai later told AP Tokyo Bureau Chief Russell Brines that he was the one who shot down the B-17 piloted by Captain Colin P. Kelly, but reported it as "unconfirmed victory" because he didn't witness its final crash. However, Sakai's name is not in the Tainan Air Group's records for engaging the B-17 that day. Combat reports indicate a joint victory by Mitsuo Toyota, Tsunahiro Yamagami, Toshio Kikuchi, Hideo Izumi, and Saburo Nozawa.

Starting December 25, the Tainan Air Group progressively advanced to Jolo Island in the Sulu Archipelago. On January 16, 1942, they moved to Tarakan Island in the Dutch East Indies. On January 24, while patrolling over Balikpapan, Borneo, Sakai discovered a formation of seven B-17 bombers from the US Army's 19th Bomb Squadron. Four Tainan Air Group Zeros (Sakai, Matsuda, Tanaka, Fukuyama) attacked for 20 minutes, severely damaging three of them. On January 25, Sakai advanced to Balikpapan Base. On February 5, Sakai took off from the base and shot down a P-40 from the US Army's 20th Pursuit Squadron over Surabaya, Java. On February 8, as commander of the second flight of nine planes (Shingo, Tanaka, Honda / Sakai, Yamagami, Yokoyama / Saeki, Nozawa, Ishii), he took off from Balikpapan Base. They engaged a formation of nine B-17s from the US Army's 19th Bomb Squadron over Kangean Island in the Java Sea, which were en route to bomb the Makassar area on Sulawesi, where the Japanese Army had begun landing. The Zero formation approached from behind and attacked the B-17s from the front, where their defensive fire was considered weaker. They jointly shot down two B-17s and severely damaged four others.

On February 18, over 13 K ft (4.00 K m) above Maospati Base in Java, Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia), Sakai jointly shot down a Fokker C.XI-W seaplane reconnaissance aircraft belonging to the Dutch East Indies Army. Sakai later recounted a notable incident during this period. While en route to attack an enemy base, he broke away from his formation to engage an enemy reconnaissance plane. After shooting it down, he encountered a large Douglas DC-4 transport plane, full of military personnel and civilians escaping the advancing Japanese forces, flying at low altitude over a dense jungle. Despite orders to shoot down all enemy aircraft in the area, regardless of whether they were armed or civilian, Sakai suspected the plane might be carrying important figures and decided to capture it. As he flew alongside to signal the pilot to follow him, he saw a blonde woman and a young child, along with other passengers, trembling in fear through the window. The woman reminded him of Mrs. Martin, an American who had kindly taught him English in middle school at Aoyama Gakuin. His resolve to fight vanished. He ignored his orders, flew ahead of the DC-4 pilot, and signaled him to escape, to which the pilot and passengers saluted him. Upon returning to base, he reported losing sight of the aircraft in the clouds. Earlier accounts by Sakai indicated he conducted warning shots to capture the transport, but it escaped. He later stated he changed his story for post-war publications during the occupation period to avoid being implicated as a war criminal. However, Japanese combat records for February 18 and 25 do not show Sakai encountering any transport planes during his missions. There have been unsubstantiated claims of an encounter with a Dutch nurse who was aboard the plane, but these lack specific details or verification.

On February 28, Sakai took off from Denpasar Base on Bali and, at 20 K ft (6.00 K m) above Malang, western Java, shot down a Brewster F2A Buffalo fighter (piloted by Ensign C.A. Fonk of the Dutch East Indies Army) with 160 rounds from a left vertical turn.

3.2.2. New Guinea and Rabaul Campaigns

On April 1, 1942, the Tainan Air Group was reorganized into the 25th Air Flotilla and transferred to the Rabaul area. On April 16, the unit advanced to Rabaul, New Britain, and on April 17, to Lae Base in eastern New Guinea, which served as a forward operating base. Due to its proximity to the Allied (US-Australian) Port Moresby base, the Tainan Air Group engaged in attacks on Port Moresby and intercepted Allied bombing raids on Lae. During this period, Sakai reportedly developed a tactic of stalking isolated, unsuspecting enemy aircraft from behind and below, using their blind spots to gain an advantageous position for a surprise attack, a method he playfully referred to as "picking up fallen ears of rice."

On May 27, 1942, Sakai participated in the Port Moresby attack with 18 Zeros under Flight Leader Major Tadashi Nakajima. After a minor dogfight, Sakai, along with his fellow aces Hiroyoshi Nishizawa and Toshio Ota, secretly agreed to break formation and perform three consecutive formation loops over the Seven Mile Airfield in Port Moresby. They claimed the enemy observed this with admiration and did not attack. Sakai later recounted that a letter of commendation from the enemy reached their base, leading to a reprimand from his superior, Sasai, for their "reckless" act. Sakai's autobiography, Samurai!, places this event on May 17. Martin Caidin, the co-author of Samurai!, claimed to have heard an account of this from a US soldier in Port Moresby after the war. However, combat records indicate that on May 17, 13 planes returned to Lae at 11:45 AM, and 2 to Salamaua. On May 27, 27 Zeros under Masao Yamashita departed Lae at 8:50 AM, engaged over Moresby, and all returned to Lae at 11:30 AM. Furthermore, Sakai was a flight leader, and the three pilots were not in the same squadron. No Japanese or Allied records confirm this separate maneuver on those dates or any other.

On June 9, 1942, Sakai participated in intercepting enemy bombers. Former US President Lyndon B. Johnson, then a Congressman, claimed his B-26 Marauder bomber was nearly shot down during this engagement. However, official records indicate Johnson's aircraft returned due to engine trouble and did not engage in combat.

3.2.3. Guadalcanal Campaign

On August 3, 1942, Sakai's air group was relocated from Lae to the airfield at Rabaul. On August 7, news arrived that US Marines had landed that morning on Guadalcanal. The initial Allied landings captured an airfield, later named Henderson Field by the Allies, which had been under construction by the Japanese. The airfield soon became the focus of months of fighting during the Guadalcanal Campaign, as it enabled US airpower to hinder the Japanese in their attempts at resupplying their troops. The Japanese made several attempts to retake Henderson Field that resulted in almost daily air battles for the Tainan Air Group.

US Marines flying Grumman F4F Wildcats from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal were using a new aerial combat tactic, the "Thach Weave", which was developed in 1941 by the US Navy aviators John Thach and Edward O'Hare. The Japanese Zero pilots flying out of Rabaul were initially confounded by the tactic. Sakai described the reaction to the Thach Weave when they encountered Guadalcanal Wildcats using it: "For the first time Lt. Commander Tadashi Nakajima encountered what was to become a famous double-team maneuver on the part of the enemy. Two Wildcats jumped on the commander's plane. He had no trouble in getting on the tail of an enemy fighter, but never had a chance to fire before the Grumman's team-mate roared at him from the side. Nakajima was raging when he got back to Rabaul; he had been forced to dive and run for safety."

On August 7, Sakai and three pilots engaged an F4F Wildcat flown by Lieutenant James "Pug" Southerland of Fighting Squadron Five (VF-5), who by the end of the war became an ace with five victories. Sakai recounted the duel in his autobiography, stating that he intervened to help his wingmen, Enji Kakimoto and Hitoshi Hatou, who were being pursued by a single Grumman. Sakai claimed he shot down the Wildcat after an extended one-on-one dogfight. Southerland, however, stated that his Grumman was hit by a land attack aircraft and was smoking with jammed machine guns when it was pursued by four Zeros, eventually catching fire and forcing him to bail out. Post-war investigations of the Grumman confirmed the jammed machine guns, corroborating Southerland's account. Japanese combat reports list Sakai, Hatou, and Ichirohei Yamazaki from another unit as joint victors.

Sakai was amazed at the Wildcat's ruggedness: "I had full confidence in my ability to destroy the Grumman and decided to finish off the enemy fighter with only my 7.7 mm machine guns. I turned the 20 mm cannon switch to the 'off' position and closed in. For some strange reason, even after I had poured about five or six hundred rounds of ammunition directly into the Grumman, the airplane did not fall, but kept on flying. I thought this very odd - it had never happened before - and closed the distance between the two airplanes until I could almost reach out and touch the Grumman. To my surprise, the Grumman's rudder and tail were torn to shreds, looking like an old torn piece of rag. With his plane in such condition, no wonder the pilot was unable to continue fighting! A Zero which had taken that many bullets would have been a ball of fire by now."

Not long after he had downed Southerland, Sakai was attacked by a lone Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bomber flown by Lieutenant Dudley Adams of USS Wasp (CV-7)'s Scouting Squadron 71 (VS-71). Adams sent a bullet through Sakai's canopy, narrowly missing the ace's head, but Sakai quickly gained the upper hand and succeeded in downing Adams. Although Adams bailed out and survived, his gunner, RM3/c Harry Elliot, was killed in the encounter. According to Sakai, that was his 60th victory.

3.2.4. Combat Skills and Tactics

Saburō Sakai was renowned for his exceptional combat skills, although his claimed aerial victories and accounts of combat have been subject to considerable scrutiny and controversy. Official Japanese records credit him with 28 aerial victories, a number significantly lower than the 64 claims made in his autobiography Samurai! and propagated by his ghostwriter, Martin Caidin. Sakai himself admitted in later interviews that he did not know the exact number of his kills, stating it might be "far fewer or even more than sixty-four," and that Caidin might have derived the number 64 from Miyamoto Musashi's sword duels.

Sakai often asserted that he never lost a wingman in combat and never had his own aircraft severely damaged. However, these claims are contradicted by official records. For instance, on May 12, 1942, his wingman Tamio Kobayashi crash-landed and his plane sank after being hit by enemy fire (Kobayashi sustained minor injuries). Also, on June 24, 1944, during an engagement over Iwo Jima, two of his wingmen, Petty Officer First Class Mio Kashiwagi and Petty Officer Jū Noguchi, did not return. Furthermore, his claim of never damaging his plane is false; his aircraft required repairs after being hit on December 12, 1941.

Regarding his combat philosophy, Sakai emphasized that a fighter pilot's ultimate reliance is on themselves. He believed that in dogfights, absolute perseverance was key, and those who pushed through the most difficult moments with a belief in victory would prevail. His iron will was critical, especially in desperate situations. He stressed the importance of vigilance, advocating a "two parts forward, nine parts backward" scanning method when entering combat airspace, and excelling at scanning above the horizon. His primary rule for aerial combat was to spot the enemy first and maneuver into a position to shoot without being targeted, likening the pilot's movement to that of a "sheepdog." He considered dogfighting as a last resort in desperate situations, preferring a "standing kill" achieved through overwhelming surprise attacks. He favored attacking from directly behind and below, exploiting the enemy's blind spot and causing them to expose themselves by tilting their wings. While his autobiography describes "left turn twists" for kills, Sakai later denied ever using this maneuver in actual combat. He attributed his ability to shoot down enemies without frequent dogfights to his exceptional eyesight, claiming he could see enemies 66 K ft (20.00 K m) to 82 K ft (25.00 K m) away. He also claimed to have improved his vision by looking at stars during the daytime.

Sakai had a mixed view of the Zero's 20mm cannon, calling it a "piss-ball" due to its slow muzzle velocity and low accuracy, and noting the danger of explosive ammunition if hit. However, he also acknowledged its devastating power, stating that "one hit on the enemy's wing root would split the wing in half." He claimed most of his kills were with the 7.7mm machine guns mounted in the nose. He expressed envy for American fighters' 13mm cannons.

Sakai held strong, critical views on the Japanese military's leadership and the Kamikaze special attack missions. He stated that he would tell kamikaze pilots "You're going sooner or later anyway, so you might as well hit your target. Listen to me: never go in too steeply." After the war, he described being ordered to undertake a kamikaze mission on Iwo Jima (though official records contradict this) as both an "honor" and a feeling of "why me?" He vehemently criticized the Imperial General Headquarters' claims that kamikaze missions boosted morale, calling it a "big lie" that severely depressed morale. He also criticized the practice of self-destruction orders issued to land attack crews who had been captured and returned, claiming such orders were given by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto and General Takijiro Onishi, despite factual inconsistencies in his account.

3.2.5. Injury and Recovery

Shortly after he had downed Southerland and Adams, Sakai spotted a flight of eight aircraft orbiting near Tulagi. Believing it to be another group of Wildcats, Sakai approached them from below and behind, aiming to catch them by surprise. However, he soon realised that he had made a mistake - the planes were in fact carrier-based bombers with rear-mounted machine guns. Despite that realization, he had progressed too far into the attack to back off, and had no choice but to see it through.

In Sakai's account of the battle, he identified the aircraft as Grumman TBF Avengers and stated that he could clearly see the enclosed top turret. He claimed to have shot down two of the Avengers (his 61st and 62nd victories) before return fire had struck his plane. The kills were seemingly verified by the three Zero pilots following him, but no Avengers were reported lost that day. However, according to US Navy records, only one formation of bombers reported fighting Zeros under these circumstances. This was a group of eight SBD Dauntlesses from Enterprise, led by Lieutenant Carl Horenberger of Bombing Squadron 6 (VB-6). The SBD crews reported being attacked by two Zeros, one of which came in from directly astern and flew into the concentrated fire from their rear-mounted twin 0.3 in (7.62 mm) .30 AN/M2 guns. The rear gunners claimed the Zero as a kill when it dived away in distress, in return for two planes damaged (one seriously).

Whatever the case, Sakai sustained serious wounds from the bombers' return fire. He was hit in the head by a .30 caliber bullet, which injured his skull and temporarily paralyzed the left side of his body. The wound is described elsewhere as having destroyed the metal frame of his goggles and "creased" his skull, a glancing blow that broke the skin and made a furrow, or even cracked the skull but did not actually penetrate it. Shattered glass from the canopy temporarily blinded him in his right eye and severely reduced vision in his left eye. The Zero rolled inverted and descended towards the sea. Unable to see out of his left eye because of the glass and the blood from his serious head wound, Sakai's vision started to clear somewhat as tears cleared the blood from his eyes, and he pulled his plane out of the dive. He considered ramming an American warship: "If I must die, at least I could go out as a samurai. My death would take several of the enemy with me. A ship. I needed a ship." Finally, the cold air blasting into the cockpit revived him enough to check his instruments, and he decided that by leaning the fuel mixture, he might be able to return to the airfield at Rabaul.

Although in agony from his injuries, Sakai managed to fly his damaged Zero in a 4 hour 47 minute flight over 560 nmi back to his base on Rabaul by using familiar volcanic peaks as guides. When he attempted to land at the airfield, he nearly crashed into a line of parked Zeros, but after circling four times and with the fuel gauge reading empty, he put his Zero down on the runway on his second attempt. He later recounted that one more circle would have led to a crash due to fuel exhaustion. After landing, he insisted on making his mission report to his superior officer, and then collapsed. Nishizawa drove him to a surgeon. Sakai was evacuated to Japan on August 12 and there endured a long surgery without anesthesia. The surgery repaired some of the damage to his head but was unable to restore full vision to his right eye. Nishizawa visited Sakai, who was recuperating in the hospital in Yokosuka. Junichi Sasai reportedly told Sakai, "Parting with you is harder than for you," and gave him a tiger belt buckle for good luck. Sakai was unaware of Sasai's death for six months, and upon learning, he expressed deep regret that he couldn't have saved him.

After his hospital discharge in January 1943, Sakai spent a year training new fighter pilots. He found the new generation of student pilots, who typically outranked veteran instructors, to be arrogant and unskilled. He admitted to striking poorly performing trainees with a bat, justifying it by the high casualty rates in Rabaul and the need for immediate improvement. His right eye had virtually no vision, and his left eye's vision had dropped to 0.7 (20/30 in American standard), with his left side still numb. Despite being told he would be unable to serve as a pilot or even a military officer, he was encouraged to become an acupuncturist or masseur. When transferred to Sasebo Hospital, he pleaded with Commander Yasuna Kozono of the reformed 251st Air Group (formerly Tainan Air Group), arguing he was more capable than inexperienced pilots, even with one eye. Kozono agreed to let him train, with a plan to make him an instructor if he couldn't fly.

3.2.6. Later War Activities

In October 1942, Sakai was promoted to Warrant Officer. In February 1943, he returned to flight status at Toyohashi Air Group for training, but in April, just before a planned deployment to Rabaul, he was transferred to Ōmura Air Group and assigned as an instructor.

On April 13, 1944, Major Tadashi Nakajima, Sakai's former superior from the Tainan Air Group, summoned him to the Yokosuka Naval Air Group. Nakajima believed Sakai's vision had recovered sufficiently for combat and that his presence would boost the morale of younger pilots. Thus, Sakai returned to the front lines despite his incomplete right eye recovery. The Yokosuka Air Group's detachment, tasked with Iwo Jima's defense and attacking US naval forces after the Battle of the Philippine Sea, was integrated into the "Hachiman Air Raid Force" with other units.

Sakai's autobiography claims he fought on Iwo Jima on June 24, July 4, and July 5. However, combat reports only confirm his participation in an interception and attack mission on June 24. On the morning of June 24, as the Hachiman Air Raid Force assembled, approximately 70 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters from US Navy Task Force 58 attacked Iwo Jima. Fifty-seven Japanese fighters, including 25 from Yokosuka Air Group, scrambled for interception. Sakai's flight, taking off later, engaged the Hellcats at 9.8 K ft (3.00 K m) beneath a thick cloud layer. Sakai claimed to have shot down two Hellcats, noting he fought with restricted vision in his right eye, forcing him to turn his head to compensate. At the end of this dogfight, Sakai, due to poor vision, mistakenly joined a formation of 15 returning Hellcats, believing them to be friendly Zeros, and was surrounded. He claimed to have escaped by performing only left turns. Witnesses, however, stated he maneuvered both left and right, and was surrounded by four Hellcats in a Lufbery circle. Sakai later claimed that a surviving US pilot told him that 100 Grumman fighters could not have shot him down with his flying style. However, two of Sakai's wingmen, Petty Officer First Class Mio Kashiwagi and Petty Officer Jū Noguchi, were lost during this morning engagement.

Combat reports indicate that on the afternoon of June 24, Sakai participated in an attack on the US task force, comprising 23 Zeros, 3 Suisei dive bombers, and 9 Tenzan torpedo bombers. In contrast, Sakai's book states that after the morning engagement, he was grounded for several days due to his injuries. He claims that on July 4, he was ordered to lead a kamikaze mission with 8 Tenzans and 9 Zeros against the US fleet, with orders not to engage in aerial combat but to crash into enemy carriers. This mission, he asserted, was tracked by US radar and attacked by Hellcats, leading to the destruction of many Tenzans. Sakai claimed to have shot down one Hellcat, then, having lost his wingmen and unable to locate the fleet in worsening weather, made a miraculous return to Iwo Jima after sunset using his intuition. He stated that upon reporting to Commander Miura, the latter only said, "Thank you for your hard work," which Sakai felt was an expression of Miura's discomfort with their survival. However, combat records indicate that the unit's overall losses on that mission included 10 Zeros and 7 Tenzans, with no mention of kamikaze orders for Sakai's unit. Furthermore, Commander Yamaguchi, whom Sakai claimed died in this attack, actually died on July 4 during a different engagement, and all remaining Japanese aircraft were destroyed by naval gunfire.

In August 1944, Sakai was commissioned an Ensign (少尉). In December of the same year, he was assigned to the 343rd Air Group (Tsurugi Unit) and its 701st Fighter Squadron (Ishinsō), where he instructed on the new Shiden-Kai fighter. He initially praised the Shiden-Kai's innovative design and excellent performance, despite its limited range, but later criticized it as a "half-baked fighter," neither a true air superiority nor an interceptor. His air combat lectures to young pilots were unpopular, often perceived as "old stories," and his use of violence drew resentment, particularly from Shoichi Sugita, an ace with more kills than Sakai, who had remained on the front lines after Sakai's injury. Sugita criticized Sakai's injury account, calling it "fake," and expressed a desire to "punch him." Flight Commander Yoshio Shiga, facing escalating tensions, decided to transfer Sakai to the Yokosuka Air Wing for flight testing, exchanging him with Kin-yoshi Muto. Yokosuka Air Wing initially resisted, but a 2-for-1 trade (Sakai and Takejiro Noguchi for Muto) was agreed upon. Muto's subsequent death in combat over the Bungo Strait made Sakai feel that Muto had died in his place.

Around the same time, Sakai married his cousin Hatsuyo, who asked him for a dagger so that she could kill herself if he fell in battle. His autobiography, Samurai!, ends with Hatsuyo throwing away the dagger after Japan's surrender and saying that she no longer needed it.

Saburō Sakai participated in the IJN's last wartime mission by attacking two reconnaissance B-32 Dominators on August 18, 1945, which were conducting photo-reconnaissance and testing Japanese compliance with the ceasefire. He initially misidentified the planes as B-29 Superfortresses. Both aircraft returned to their base at Yontan Airfield, Okinawa. One B-32 crewman was killed and two injured, marking the last American combat fatality of World War II. While Sakai claimed to have engaged them in his Zero, other pilots like Sadamu Komachi stated a Zero would have been ineffective against a B-32, implying Sakai did not effectively engage. However, Ryoji Ohara, another Petty Officer, claimed to have engaged a B-32 in his Zero Model 52 that day. This encounter was not included in Samurai!. After the war ended, Sakai was promoted to Sub-Lieutenant (中尉).

4. Post-War Life

After the end of World War II, Saburō Sakai faced significant challenges transitioning to civilian life.

4.1. Civilian Life and Business

Upon his discharge from the Imperial Japanese Navy after the war, Sakai became a Buddhist acolyte and made a vow never again to kill any living creature, not even a mosquito. He serenely accepted Japan's defeat, stating, "Had I been ordered to bomb Seattle or Los Angeles in order to end the war, I wouldn't have hesitated. So I perfectly understand why the Americans bombed Nagasaki and Hiroshima."

Times were difficult for Sakai in the immediate post-war period, and he struggled to find stable employment. In 1952, he remarried and established a printing shop. His post-war career was also marked by his association with controversial pyramid scheme organizations. He participated in the 'Tenka Ikka no Kai' (天下一家の会Tenka Ikka no KaiJapanese), a Ponzi scheme started by his former subordinate Kenichi Uchimura. Sakai became a prominent figure in the organization, inviting most of his former NCO pilots to join, which resulted in losses for many. As lawsuits mounted and the pyramid scheme became a major social problem, Sakai's image suffered. In 1976, his autobiography Ōzora no Samurai (Samurai!) was adapted into a film funded by 'Taikan-gu' (Taikan Production), a religious corporation associated with the 'Tenka Ikka no Kai'. This led to the temporary dissolution of the "Zero Fighter Pilots' Association," which then reformed to distance itself from Sakai, fearing association with the pyramid scheme. Sakai's public image and standing among his former comrades diminished significantly.

However, Sakai's popularity gradually recovered. He began writing a life advice column for Weekly Playboy magazine, and publishing professionals formed a support group called "Zero no Kai" to promote him. American naval personnel at Atsugi and Yokosuka naval bases initially showed little interest in Sakai compared to other Zero pilots like Ryoji Ohara, but Sakai's profile grew over time.

4.2. Personal Life and Family

Sakai's first wife, Hatsuyo, passed away in 1947. He remarried in 1952 to Haru. He had two daughters and one son. In a notable gesture, he sent his daughter to college in the United States "to learn English and democracy." His daughter, Michiko Sakai Smart, later confirmed that she was aware of the various criticisms and controversies surrounding her father, including the ghostwriting and the pyramid scheme, stating that he had told her about them himself.

5. Evaluation and Legacy

Saburō Sakai's life and career left a complex legacy, marked by both remarkable achievements and significant controversies, influencing popular culture and prompting reflections on war and military ethics.

5.1. Writings and Controversies

Sakai's autobiography, Samurai!, published in English, became widely known internationally. However, its authenticity and factual accuracy have been critically examined. It is widely alleged that the book was ghostwritten, primarily by Martin Caidin in collaboration with Fred Saito, based on Sakai's interviews. Japanese sources indicate that the Japanese version, Sakai Saburō Kūsen Kiroku, was written by Masayuki Fukubayashi based on Sakai's accounts and his own research. The Japanese version, Ōzora no Samurai, was then reportedly adapted by Kojinsha president Hajime Takashiro for a Japanese audience, in consultation with Sakai, to align with the American "air combat action" style of Samurai!. Sakai himself, when questioned by professor Kanichiro Kato, claimed he wrote every word himself, enduring multiple revisions, though he sometimes sought publishers' opinions on chapter order.

Despite Sakai's claims, numerous contradictions have been identified between his various published works and actual historical records, particularly concerning his claimed kill counts and specific combat incidents. The claimed 64 victories in Samurai! are significantly higher than the 28 officially recognized by Japanese records. Martin Caidin is believed to have inflated these numbers to boost book sales. Sakai himself later conceded that he did not precisely know his true kill count, suggesting it could be higher or lower than 64.

The book Samurai! gained significant cultural impact, with the Iraqi military reportedly making its Arabic translation mandatory reading for pilots to boost morale. However, within Japan's military aviation circles and among other Japanese pilots, Sakai's reputation was mixed. Aviation historian Yoji Watanabe expressed little interest in interviewing Sakai, implying that many other pilots had more significant contributions. The Japan Air Self-Defense Force reportedly advised against getting too close to Sakai, viewing him as overly self-promotional, a "mere craftsman," and someone who fought only for himself. They believed many other pilots were more skilled but less famous. Sakai, however, took pride in the "craftsman" label, stating it was their "pride" and "reason for existence."

Sakai's post-war criticisms of the Japanese military's high command were extensive, but these critiques often contained factual errors or falsehoods. For example, his assertion that Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto ordered land attack crews, rescued after forced landings, to self-destruct is contradicted by records indicating such orders came from the 11th Air Fleet, without Sakai's involvement. He also made initial-only criticisms of former superior officers, leading to unwarranted speculation about others with the same initials, and often alienated fellow NCO and enlisted pilots who resented his criticisms of their own admired officers and his perceived self-aggrandizement.

Sakai frequently asserted that Japan's failure to rigorously address the Emperor's war responsibility was the root cause of contemporary Japanese politicians and large corporations avoiding accountability for their mistakes. He also critically referred to Japanese people as "one hundred million parasites," arguing that Japan's post-war material prosperity was solely due to "parasitizing" America. He contrasted Japan's lack of "blood or sweat" in the post-war era with South Korea's sacrifices in the Korean War and Vietnam War, which he believed justified South Korea's request for financial aid from Japan.

A support group for Sakai, "Zero no Kai," composed of publishing industry professionals, actively promoted him and continued its activities even after his death.

5.2. Cultural Impact

Sakai's life and achievements have been portrayed in popular culture, contributing to his enduring legacy. The 1976 Japanese film Zero Pilot, starring Hiroshi Fujioka as Sakai, dramatized his experiences, with its screenplay based on his book Samurai!. In the year 2000, shortly before his death, Sakai served as a consultant for the development of Microsoft Combat Flight Simulator 2, a flight simulation video game. He worked alongside American Marine Corps fighter ace Joe Foss on the project. A planned in-game air combat between Sakai and Foss was anticipated but never materialized due to Sakai's passing before the game's completion.

5.3. Reconciliation and Encounters

Sakai's post-war life included notable efforts toward reconciliation with former adversaries. He visited the United States and met many American pilots he had fought against. A significant encounter was with Lieutenant Commander Harold "Lew" Jones (1921-2009), the SBD Dauntless rear-seat gunner (piloted by Ensign Robert C. Shaw) who had wounded him during the Guadalcanal campaign. They met on Memorial Day in 1982, with Sakai holding his tattered flight helmet from that fateful mission. He also met with Sam Gracio, the American P-40 pilot he had shot down in the Philippines, confirming their shared memory of the aerial combat. Sakai recounted meeting other American pilots who reportedly praised his evasion skills, claiming that even 100 Grumman Hellcats could not have shot him down.

In 1983, Sakai was invited to the Alabama Air Force's Bicentennial Aviation Festival, where he met Paul Tibbets, the pilot of the Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Sakai publicly lauded Tibbets for fulfilling his military orders, stating that he too would have carried out the atomic bombing if ordered to bomb American cities like Seattle or Los Angeles to end the war. This stance drew considerable criticism from atomic bomb survivors. However, Sakai clarified that he held President Harry S. Truman responsible for the moral implications of the atomic bombings, not Tibbets personally.

5.4. Views on War and Military Leadership

Throughout his post-war life, Saburō Sakai became an outspoken critic of Japanese military leadership during World War II, as well as an observer of modern Japanese society. He often presented himself as a researcher of the Pacific War.

Sakai strongly condemned the Japanese military's perceived disregard for human life and its emphasis on "spiritual power" over rational strategy. He famously criticized the kamikaze special attack missions as an "insane" plan that only served to demoralize troops, contrasting with the official narrative of boosted morale. He would often advise kamikaze pilots to aim for precision rather than simply sacrificing themselves, instructing them to maintain shallow attack angles to improve their chances of hitting targets.

Sakai's critical remarks extended to post-war Japan. He argued that the nation's economic prosperity was a result of "parasitizing" the United States, rather than Japanese diligence. He once famously responded to a question about whether cars or fighter planes were better by saying, "Cars are definitely better. Because cars can reverse." He also expressed disappointment in contemporary Japanese youth, describing them as lacking ambition and being undisciplined, though he tempered this view in a televised debate by acknowledging that older generations have always criticized younger ones. In his later years, he drove a first-generation Roadster, citing its good visibility, similar to a fighter plane.

He also provided advice to manga artist Shigeru Mizuki, telling him that "war stories must win" to sell. Mizuki, who served during Japan's period of military decline, found this difficult to implement given his own experiences of defeat. Sakai's critiques of former superiors, often using only initials, caused distress for others with the same initials and alienated many former NCOs who respected those officers. His daughter, Michiko, later confirmed that her father shared these controversial views with her privately, suggesting they were deeply held beliefs.

Sakai maintained his physical fitness well into old age, keeping an iron bar for pull-ups and hanging exercises at home, surprising many visitors with his ability to perform pull-ups even in his 70s.

6. Death

Saburō Sakai died on September 22, 2000, at the age of 84. He had been invited as a guest of honor to a change-of-command ceremony at Atsugi Naval Air Station, a US military base in Japan. After the formal dinner, he complained of feeling unwell and collapsed while returning home. He was taken to a US naval hospital, where he passed away later that night from a heart attack. His last words to his doctor were reportedly, "May I sleep now?"

His funeral was attended by only four of his former Zero pilot comrades, despite a larger gathering of about 30 former Zero pilots nearby. This low attendance from his peers reflected the long-standing resentment and controversies surrounding his post-war actions and statements, including the ghostwriting allegations and his involvement in the pyramid scheme. He was survived by his second wife, Haru, and his two daughters and a son.