1. Overview

Paul Claudel (Paul Claudelpɔl klodɛlFrench; 1868-1955) was a prominent French poet, dramatist, and diplomat, widely recognized as one of the most significant figures in French literature during the first half of the 20th century. His multifaceted career saw him serve extensively in the French diplomatic corps across various continents, while simultaneously producing a prolific body of literary work. Claudel is particularly celebrated for his powerful verse dramas, which often convey his profound Catholic faith and explore themes of sacrifice, divine love, and human longing. He developed a distinctive poetic style known as the "verset claudelien," a form of free verse that reflected his unique artistic vision. His personal life was marked by a pivotal religious conversion experience and a complex relationship with his elder sister, the renowned sculptor Camille Claudel.

2. Early Life and Education

Paul Claudel's formative years were shaped by his family background, early academic pursuits, and a transformative religious experience that profoundly influenced his worldview and artistic expression.

2.1. Birth and Family

Paul Louis Charles Marie Claudel was born on August 6, 1868, in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, a village in the Aisne department of northern France. His family had roots in farming and government service. His father, Louis-Prosper Claudel, worked in mortgages and banking, while his mother, Louise Cerveaux, came from a Catholic family of farmers and priests in Champagne. Paul was the youngest of four children, including his elder sister, Camille Claudel, who would become a celebrated sculptor. The family moved frequently due to his father's transfers as a tax collector, before settling in Paris in 1881.

2.2. Education and Religious Conversion

Claudel began his education in Champagne before attending the lycée of Bar-le-Duc. In 1881, following his family's move to Paris, he enrolled at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. He passed his baccalaureate in 1884 and advanced to a philosophy class, where he frequented concerts with his classmate, Romain Rolland. In 1885, he began studying law at the University of Paris.

A pivotal moment in Claudel's life occurred on Christmas Day 1886. Though an unbeliever in his teenage years, he experienced a profound religious conversion at the age of 18 while listening to a choir sing Vespers in Notre-Dame de Paris. He described this experience as instantaneous: "In an instant, my heart was touched, and I believed." This spiritual awakening transformed him into a fervent Catholic, a faith he actively practiced for the remainder of his life and which became central to his literary and philosophical outlook.

During this period, Claudel also discovered the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud, particularly *Illuminations* and *Une Saison en Enfer*, which deeply influenced him. From 1887, he began attending the "Tuesday meetings" of Stéphane Mallarmé, another significant literary influence. He dedicated himself to the "revelation through poetry, both lyrical and dramatic, of the grand design of creation." He also studied at the Paris Institute of Political Studies.

3. Diplomatic Career

Paul Claudel embarked on an extensive and distinguished career in the French diplomatic service, spanning from 1893 to 1936. Despite initially considering a monastic life, he chose diplomacy, which provided him with opportunities to travel the world and observe diverse cultures, profoundly enriching his literary work.

3.1. Major Postings and Activities

Claudel's diplomatic career began in April 1893 as a vice-consul in New York City, followed by a posting in Boston in December of the same year. From 1895 to 1909, he served as a French consul in China, with assignments in Shanghai (June 1895), Fuzhou (October 1900, as vice-consul), Hankou (as acting vice-consul), Beijing (as first secretary of the legation), and Tianjin (1906-1909, as consul). During a break from his Chinese postings in 1900, he spent time at Ligugé Abbey, considering entry into the Benedictine Order, but this was postponed.

After his final posting in China, Claudel served in a series of European cities leading up to World War I. He was in Prague (December 1909), Frankfurt am Main (October 1911), and Hamburg (October 1913). During this period, he showed interest in the theatre festival at Hellerau and the ideas of Jacques Copeau. He was in Rome from 1915 to 1916.

During World War I, Claudel served as ministre plénipotentiaire in Rio de Janeiro (1917-1918), where he oversaw the crucial provision of food supplies from South America to France. His secretaries during this mission included the composer Darius Milhaud, who later wrote incidental music for several of Claudel's plays. Subsequent postings included Copenhagen (1920), Tokyo (1921-1927), Washington, D.C. (1928-1933), where he became Dean of the Diplomatic Corps in 1933, and Brussels (1933-1936).

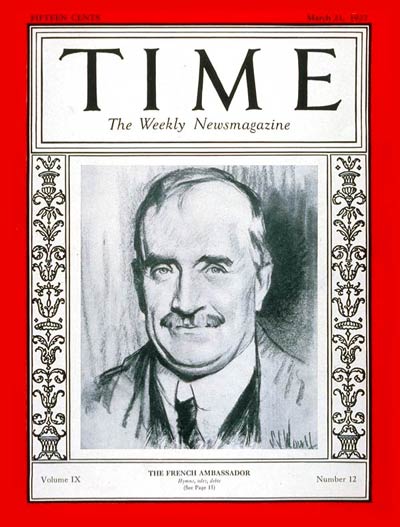

Early in his diplomatic career, Claudel often published his literary works anonymously or under a pseudonym, as permission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was required for publication. This meant he remained relatively obscure as an author until 1909. In that year, the founding members of the Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF), particularly his friend André Gide, were eager to recognize his work. Claudel sent them his poem Hymne du Sacre-Sacrement for their first issue, which was published under his own name without seeking official permission. This caused a stir, with Claudel facing criticism, including attacks based on his religious views. However, with the advice of his close friend Philippe Berthelot of the Foreign Ministry, he ignored the critics, and this incident marked the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration between Claudel and the NRF.

3.2. Ambassadorship in Japan

Paul Claudel's tenure as the French Ambassador to Japan, from November 19, 1921, to February 17, 1927, was a significant period in both his diplomatic and literary life. During this time, relations between France and Japan were relatively harmonious, with few conflicting issues. Claudel was sympathetic to Japan, which was increasingly isolated from the Anglo-American powers, and he sought to foster mutual understanding regarding their respective interests in East Asia, such as France's in French Indochina and Japan's in China. He also demonstrated international business acumen, anticipating Japan's increased focus on air power after the Washington Naval Treaty and promoting the sale of French aircraft.

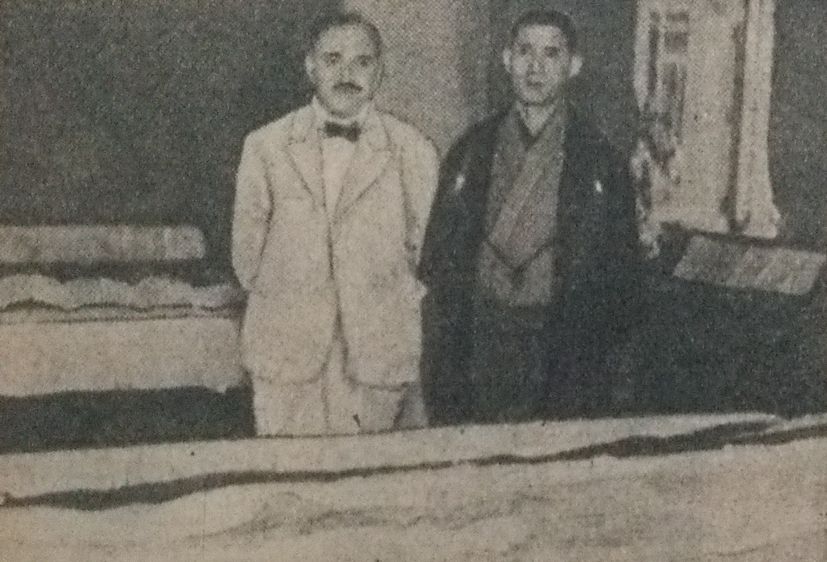

Influenced by his sister Camille's interest in Japonism, Claudel held a deep appreciation for Japanese art and culture. Despite his demanding official duties, he actively explored various parts of Japan, including Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and Fukuoka. He frequently lectured to students and immersed himself in traditional Japanese performing arts, attending performances of Bugaku (such as *Shun'ōraku* and *Nasori*), Bunraku, Kabuki (*Kanadehon Chūshingura*, *Ishikiri Kajiwara*), and Noh (*Dōjōji*, *Okina*, *Sumidagawa*, *Kinuta*). He visited numerous cultural sites, including Daitoku-ji, Daikaku-ji, Ryōan-ji, Hase-dera, Nijō Castle, Sanzen-in, and Nagoya Castle, and admired the *fusuma-e* paintings of the Kanō school. He cultivated friendships with prominent Japanese artists like Tomita Keisen, Yamamoto Shunkyo, and Takeuchi Seihō, as well as Kabuki actor Nakamura Fukusuke V and Nagauta musician Kineya Sakichi IV.

During his time in Japan, Claudel contributed articles in French, accompanied by Japanese translations, to magazines such as *Kaizō* and *Shincho*. He also published several poetry collections through Japanese bookstores, including *Sainte Geneviève*, *Shifūjō*, *Kijibashishū*, and *Hyakusenjō*. He wrote the dance-drama *La Femme et son Ombre*, which was staged at the Imperial Theatre by Matsumoto Kōshirō VII and Nakamura Fukusuke V.

Claudel was present in Tokyo during the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. He actively directed relief efforts, establishing temporary hospitals and nurseries. He was notably impressed by the disciplined behavior of the Japanese people, observing their calm and orderly queues for supplies, writing that he "did not hear a single complaint" and that people "all seemed to be quietly waiting, as if they were on the same small boat."

On March 7, 1924, Claudel collaborated with Shibusawa Eiichi to establish the Maison Franco-Japonaise (Nichifutsu Kaikan), a key institution for Franco-Japanese cultural exchange. In 1926, he also promoted the establishment of the Institut français du Japon - Kansai (Kansai Nichifutsu Gakkan) with Inabata Katsutarō, though its opening on October 22, 1927, occurred after he had departed for his ambassadorship in the United States.

Years later, in 1943, Claudel expressed his admiration for the Japanese people. According to Henri Mondor, Claudel stated at a duchess's evening party that he wished the Japanese people would "never be crushed," praising their "ancient civilization so interesting" and asserting that "no people deserves its prodigious expansion better." He acknowledged their poverty but emphasized their nobility despite their large population.

3.3. Diplomatic Stance and Views

Paul Claudel was a staunch conservative with views that reflected the traditional, often controversial, stances of conservative France, including elements of antisemitism. Following France's defeat in 1940 during World War II, he addressed a poem titled "Paroles au Maréchal" ("Words to the Marshal") to Philippe Pétain, commending him for attempting to salvage France's "broken, wounded body." As a devout Catholic, he expressed a sense of satisfaction at the fall of the French Third Republic, which he viewed as anti-clerical.

However, his personal diaries reveal a consistent contempt for Nazism, which he condemned as early as 1930 as "demonic" and "wedded to Satan," often referring to both communism and Nazism as "Gog and Magog." In 1935, he wrote an open letter to the World Jewish Conference, explicitly condemning the Nuremberg Laws as "abominable and stupid."

Despite his initial support for the Vichy regime, Claudel disagreed with Cardinal Alfred Baudrillart's policy of collaboration with Nazi Germany. When his daughter-in-law's sister's husband, Paul-Louis Weiller, was arrested by the Vichy government in October 1940, Claudel traveled to Vichy to intercede on his behalf, though without immediate success. Weiller later escaped, with authorities suspecting Claudel's assistance, and fled to New York. In December 1941, Claudel wrote to Isaïe Schwartz, expressing his opposition to the Statut des Juifs, the antisemitic laws enacted by the Vichy regime. In response, the Vichy authorities searched Claudel's home and kept him under surveillance. His support for Charles de Gaulle and the Free France forces ultimately culminated in a victory ode dedicated to de Gaulle upon the liberation of Paris in 1944.

4. Literary Activities and Works

Paul Claudel's literary output was extensive and deeply interwoven with his spiritual and philosophical convictions. He is renowned for his distinctive style and the profound influence of his Catholic faith on his creative process.

4.1. Literary World and Influences

Claudel often acknowledged Stéphane Mallarmé as his teacher, and his poetic approach has been seen as an extension of Mallarmé's, enriched by the idea of the world itself as a revelatory religious text. He rejected traditional prosody, instead developing his own form of free verse known as the verset claudelien (Claudelian verse). This innovative style was part of a broader movement of experimentation by followers of Walt Whitman, whose work deeply impressed Claudel. Other French poets, such as Charles Péguy and André Spire, also explored similar forms of verset. The influence of the Latin Vulgate on his verse, however, has been a subject of scholarly debate.

4.2. Major Dramas

Claudel's most celebrated works are his verse dramas, which often explore complex themes of human and divine love, sacrifice, and spiritual transformation. His plays are characterized by their epic scale, poetic language, and profound theological underpinnings, though their complexity often meant a delayed positive reception by audiences.

Notable plays include:

- Le Partage de Midi (The Break of Noon, 1906): This play explores themes of passionate, obsessive human love.

- L'Annonce faite à Marie (The Tidings Brought to Mary, 1910): A mystical drama focusing on themes of sacrifice, oblation, and sanctification, told through the story of a young medieval French peasant woman who contracts leprosy. It was first performed in 1912 by the "Théâtre de l'Œuvre" at the Malakoff Theatre, directed by Aurélien Lugné-Poë. Subsequent revised versions were published in 1940 and 1948, with the latter premiering at the Théâtre Hébertot.

- Le Soulier de Satin (The Satin Slipper, 1931): An expansive exploration of human and divine love and longing, set within the Spanish Empire during its Golden Age. Its complexity and scale made it challenging to stage, but an abridged version was successfully produced at the Comédie-Française in 1943, directed by Jean-Louis Barrault. A complete version was later premiered at the Festival d'Avignon in 1987, directed by Antoine Vitez.

- Jeanne d'Arc au Bûcher (Joan of Arc at the Stake, 1939): An oratorio with music composed by Arthur Honegger. It premiered in Orléans with Ida Rubinstein in the lead role.

- L'Histoire de Tobie et de Sara (The Story of Tobias and Sarah, 1942, revised 1953): This was his final dramatic work, first produced by Jean Vilar for the Festival d'Avignon in 1947.

Many of his plays feature romantically distant settings, such as medieval France or 16th-century Spanish South America. Other significant dramas include Tête d'or (Golden Head, 1890), La Ville (The City, 1893), L'Échange (The Exchange, 1901), Le Repos du septième jour (The Rest on the Seventh Day, 1901), L'Otage (The Hostage, 1911), and Le Pain dur (The Hard Bread, 1918). He also translated Aeschylus's *Oresteia* trilogy, including *Agamemnon* (1896), *Les Choéphores* (1920), and *Les Euménides* (1920), with music by Darius Milhaud.

4.3. Poetry and Poetry Collections

In addition to his dramas, Claudel was a prolific lyric poet. His major poetic works include:

- Cinq Grandes Odes (Five Great Odes, 1907): This collection is a prime example of his distinctive poetic expression. Boštjan Marko Turk's doctoral thesis, *Paul Claudel et l'Actualité de l'être* (2011), specifically examined the influence of medieval philosophy on this work.

- Connaissance de l'Est (Knowledge of the East, 1900, revised 1907, augmented 1952): This collection reflects his experiences and observations during his diplomatic postings in China.

- Poèmes de la Sexagésime (1905)

- Processionnal pour saluer le siècle nouveau (1907)

- La Cantate à trois voix (Cantata for Three Voices, 1913, published 1931)

- Corona benignitatis anni dei (1915)

- La Messe là-bas (1919)

- Poèmes de guerre (1914-1916) (1922)

- Feuilles de saints (1925)

- Cent phrases pour éventails (One Hundred Phrases for Fans, 1942): A collection of haikai-like poems, some of which were illustrated by Tomita Keisen and published in Japan as *Shifūjō*, *Kijibashishū*, and *Hyakusenjō*.

- Visages radieux (1945)

- Dodoitsu (1945): A collection inspired by Japanese *dodoitsu* short poems.

- Accompagnements (1949)

4.4. Other Writings

Claudel's literary output extended beyond drama and poetry to include a wide range of prose works, offering deep insights into his intellectual and spiritual life. These include:

- Critical essays and literary theory: Art poétique (Poetic Art, 1907), Positions et propositions (2 volumes, 1928, 1934), and L'Œil écoute (The Eye Listens, 1946), a collection of essays on painting.

- Travelogues and impressions: L'Oiseau noir dans le soleil levant (The Black Bird in the Rising Sun, 1929), a collection of his impressions of Japan, and Sous le signe du dragon (Under the Sign of the Dragon, 1948), a work on China.

- Philosophical and theological reflections: Conversations dans le Loir-et-Cher (1935), Figures et paraboles (1936), Seigneur, apprenez-nous à prier (1942), Emmaüs (1949), Une voix sur Israël (1950), Qui ne souffre pas... Réflexions sur le problème social (1958), Présence et prophétie (1958), La Rose et le rosaire (1959), and Trois figures saintes pour le temps actuel (1959).

- Biblical commentaries: Paul Claudel interroge l'Apocalypse (Paul Claudel Questions the Apocalypse, 1952), Paul Claudel interroge le Cantique des Cantiques (Paul Claudel Questions the Song of Songs, 1954), and L'Évangile d'Isaïe (The Gospel of Isaiah, 1951).

- Published diaries: His extensive diaries, *Journal. Tome I: 1904-1932* (1968) and *Journal. Tome II: 1933-1955* (1969), provide a detailed record of his thoughts and experiences.

- Extensive correspondence: Claudel maintained a vast network of correspondence with prominent literary and artistic figures, including André Gide (1899-1926), Jacques Rivière (1907-1924), André Suarès (1904-1938), Gabriel Frizeau and Francis Jammes (1897-1938), Darius Milhaud (1912-1953), Aurélien Lugné-Poë (1910-1928), Jacques Copeau, Charles Dullin, Louis Jouvet, Jean-Louis Barrault (1974), Romain Rolland (2005), and Gaston Gallimard (1911-1954). His diplomatic correspondence, such as *Correspondance diplomatique. Tokyo (1921-1927)* (1995) and *La crise: Correspondance diplomatique, Amérique 1927-1932* (1993), also offers valuable historical insights.

5. Thought and Philosophy

Paul Claudel's thought and philosophy were profoundly shaped by his unwavering Catholic faith, which served as the bedrock for his worldview and artistic creation.

5.1. Catholic Faith and Art

Claudel's deep and devout Catholicism was the central pillar of his life and work. After his conversion experience at Notre-Dame de Paris in 1886, his faith became an inseparable part of his identity and his literary mission. He famously stated that the Bible was his "pillow book" and that all his creative endeavors collectively formed a "new Bible." For Claudel, art was not merely an aesthetic pursuit but a means of spiritual revelation, a way to explore and express the divine order of creation. He believed that his writing served to praise God, transcending everyday measures in both style and subject matter. He was not concerned with "who people are" but rather "who they should become," taking on the role of a preacher through his works. This theological grounding informed his literary themes, aesthetic principles, and his unique poetic rhythm, which he believed reflected the natural cadence of the human heart and breath.

5.2. Social and Political Views

Claudel held deeply conservative political leanings, which sometimes led to controversial stances. He shared some of the antisemitic sentiments prevalent in conservative French circles of his era. His initial support for the Vichy regime after the fall of France in 1940, and his commendation of Marshal Philippe Pétain, stemmed partly from a satisfaction at the demise of the anti-clerical French Third Republic.

However, his views were complex and evolved. His diaries explicitly condemn Nazism as "demonic" as early as 1930, and he referred to both Nazism and communism as "Gog and Magog." In 1935, he publicly denounced the Nuremberg Laws as "abominable and stupid" in an open letter to the World Jewish Conference. During World War II, he actively opposed the Vichy regime's antisemitic policies, interceding for a family member arrested by Vichy authorities and writing to Isaïe Schwartz to express his opposition to the Statut des Juifs. This led to surveillance and a search of his home by Vichy authorities. Ultimately, Claudel aligned himself with Charles de Gaulle and the Free France movement, celebrating the liberation of Paris with a victory ode dedicated to de Gaulle. These actions demonstrate a nuanced and often contradictory political journey, marked by a strong sense of national identity and a deep-seated, if sometimes inconsistently applied, moral compass rooted in his faith.

6. Personal Life

Paul Claudel's private life, particularly his family relationships and significant personal experiences, played a crucial role in shaping his identity and artistic expression.

6.1. Marriage and Children

On March 15, 1906, Paul Claudel married Reine Sainte-Marie Perrin (1880-1973). She was the daughter of Louis Sainte-Marie Perrin (1835-1917), a prominent architect from Lyon known for completing the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Fourvière. Together, Paul and Reine had five children: two sons and three daughters.

Prior to his marriage, while serving in China, Claudel had a significant affair with Rosalie Vetch née Ścibor-Rylska (1871-1951). Rosalie was the wife of Francis Vetch, a Belgian businessman whom Claudel knew through his diplomatic work. They met on a sea voyage from Marseille to Hong Kong in 1900. Rosalie, who already had four children, became pregnant with Claudel's child. The affair concluded in February 1905, with Rosalie signaling its end during a meeting at a German border railway station with her husband and Claudel. Their daughter, Louise Marie Agnes Vetch (1905-1996), was born in Brussels. This passionate and obsessive relationship profoundly influenced Claudel's later dramatic works, notably Le Partage de Midi and Le Soulier de Satin.

6.2. Relationship with Sister Camille Claudel

Paul Claudel's relationship with his elder sister, the sculptor Camille Claudel, was complex and deeply troubled. Camille, a talented artist who had been the lover of Auguste Rodin, began to experience severe mental health issues. In March 1913, Paul Claudel, along with their mother, made the decision to commit Camille to a psychiatric hospital, where she would remain for the last 30 years of her life.

During this period, Paul visited his sister only seven times. Despite evidence from medical records indicating that while she had mental lapses, she was often clear-headed when working on her art, and doctors at times tried to convince the family that she did not need to be institutionalized, the family insisted on keeping her confined. This decision and Paul's limited engagement with her during her long confinement have been a source of significant criticism regarding his treatment of his sister. The tragic story of Camille's institutionalization and her relationship with Paul has been explored in various works, including Michèle Desbordes's 2004 novel La Robe bleue (The Blue Dress) and Jean-Charles de Castelbajac's 2010 song "La soeur de Paul," performed by Mareva Galanter.

7. Later Life and Retirement

After concluding his distinguished diplomatic career in 1935, Paul Claudel retired to Brangues in Dauphiné, where he had purchased a château in 1927. He continued to spend his winters in Paris.

During World War II, following the Battle of France in 1940, Claudel traveled to Algeria and offered his services to Free France. However, he did not receive a response to his offer and subsequently returned to Brangues. As noted earlier, while he initially supported the Vichy regime, he actively opposed its antisemitic policies and later aligned himself with Charles de Gaulle.

On April 4, 1946, Claudel was elected to the Académie française, taking the seat previously held by Louis Gillet. This election followed a notable rejection in 1935, when Claude Farrère was preferred over him, which was considered somewhat scandalous at the time. Over the years, Claudel was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature on six different occasions. In 1947, he suffered a heart attack. In 1948, at the request of Charles de Gaulle, he became a member of the French State Council. On October 17, 1951, he received the Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur. Despite increasing frailty, he continued his writing, travels, and involvement in theatre until his final days.

8. Reputation and Legacy

Paul Claudel's enduring impact on literature and culture is significant, though his legacy is also marked by critical evaluations and controversies surrounding his personal views and political affiliations.

8.1. Literary Evaluation

Claudel is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in French literature of the early 20th century. His unique dramatic and poetic style, particularly the verset claudelien, and the profound spiritual depth of his works, have earned him a lasting place in literary history. The British poet W. H. Auden acknowledged Claudel's literary prowess in his poem "In Memory of W. B. Yeats" (1939), stating that "Time that with this strange excuse / Pardoned Kipling and his views, / And will pardon Paul Claudel, / Pardons him for writing well." Literary critic George Steiner, in his work The Death of Tragedy, named Claudel as one of the three "masters of drama" in the 20th century, alongside Henry de Montherlant and Bertolt Brecht.

8.2. Social Impact

Claudel's works and ideas have resonated through different periods, influencing subsequent generations of writers and artists. His plays, initially slow to gain widespread theatrical acceptance due to their complexity and scale, eventually achieved significant recognition. For example, the second version of his play La Ville premiered posthumously at the Festival d'Avignon in 1955, directed by Jean Vilar. The complete version of Le Soulier de Satin also saw its acclaimed premiere at the Avignon Festival in 1987, directed by Antoine Vitez. The continued publication of his complete works and various collections ensures his ongoing presence in literary discourse. The Paul Claudel Society holds annual commemorative events at the Château de Brangues, his former residence, keeping his memory and works alive. Institutions like the Lycée Claudel, a French high school in Ottawa, Canada, are named in his honor, reflecting his broader cultural influence.

8.3. Criticism and Controversy

Despite his literary achievements, Claudel's legacy is not without its criticisms and controversies. His conservative political views, including his early support for the Vichy regime and his documented antisemitism, have been subjects of considerable debate and scrutiny. While his later opposition to Nazism and his support for Charles de Gaulle provided a more nuanced picture of his political evolution, these earlier stances remain a contentious aspect of his biography. Furthermore, his role in the institutionalization of his sister, Camille Claudel, and his subsequent limited contact with her during her three decades in a psychiatric hospital, have drawn significant criticism and continue to be a sensitive point in discussions of his personal life. Understanding Claudel's complex legacy requires acknowledging both his profound literary contributions and the problematic aspects of his personal views and actions.

9. Death

Paul Claudel died on February 23, 1955, at his home in Paris, at the age of 86. Just four days before his death, he was still actively involved in the production of his play L'Annonce faite à Marie at the Comédie-Française. A state funeral was held for him on February 28, 1955, at Notre-Dame de Paris. He was later buried on September 4, 1955, in a corner of the grounds of his château in Brangues.