1. Overview

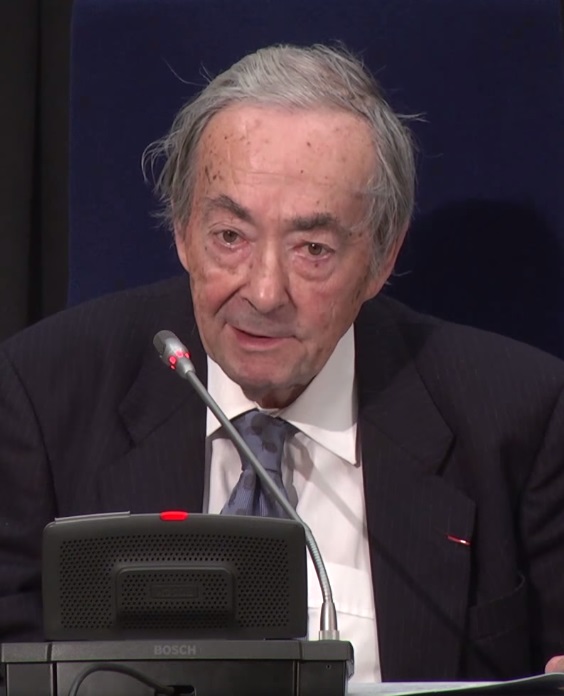

Francis George Steiner (April 23, 1929 - February 3, 2020) was a prominent Franco-American literary critic, essayist, philosopher, novelist, and educator. He wrote extensively on the intricate relationship between language, literature, and society, and profoundly explored the enduring impact of the Holocaust. Described as both a polyglot and a polymath, Steiner is credited with redefining the role of the critic by examining art and thought across national and disciplinary boundaries. English novelist A. S. Byatt lauded him as a "late, late, late Renaissance man," a "European metaphysician with an instinct for the driving ideas of our time," while former British Council literature director Harriet Harvey-Wood recognized him as a "magnificent lecturer" who could speak prophetically with minimal notes.

2. Early Life

George Steiner's formative years were deeply shaped by his Viennese Jewish heritage, a multilingual upbringing, and the profound impact of escaping Nazi persecution.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Francis George Steiner was born on April 23, 1929, in Paris, France. His parents, Else (née Franzos) and Frederick Georg Steiner, were Viennese Jewish immigrants. He had an elder sister, Ruth Lilian, born in Vienna in 1922. His mother, Else Steiner, was described as a Viennese grande dame. His father, Frederick Steiner, had been a senior lawyer at the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Austria's central bank, before becoming an investment banker in Paris. Five years before Steiner's birth, his father had moved the family from Austria to France to escape the escalating threat of anti-Semitism. Believing that Jews were "endangered guests wherever they went," Frederick Steiner ensured his children were equipped with languages. Consequently, Steiner grew up with three mother tongues: German, English, and French. His mother was notably multilingual, often beginning a sentence in one language and concluding it in another.

2.2. Education and Early Experiences

Steiner's education began at home, where his father, who emphasized classical education, taught him to read the Iliad in the original Greek at the age of six. His mother, who abhorred "self-pity," helped Steiner overcome a physical handicap he was born with, a withered right arm, by insisting he use it as an able-bodied person would. His first formal schooling took place at the Lycée Janson de Sailly in Paris.

In 1940, amidst World War II, Steiner's father, then in New York City on an economic mission for the French government, secured permission for his family to travel to New York as the Germans prepared to invade France. Steiner, his mother, and his sister Lilian departed by ship from Genoa. Within a month of their relocation, the Nazis occupied Paris. Of the many Jewish children in Steiner's class at school, he was one of only two who survived the war. This foresight by his father saved his family and instilled in Steiner a profound sense of being a survivor, which deeply influenced his later writings. He often remarked, "My whole life has been about death, remembering and the Holocaust." He considered himself a "grateful wanderer," stating, "Trees have roots and I have legs; I owe my life to that." He completed his school years at the Lycée Français de New York in Manhattan and became a United States citizen in 1944.

After high school, Steiner attended the University of Chicago, where he pursued studies in literature, mathematics, and physics, earning a BA degree in 1948. He then obtained an MA degree from Harvard University in 1950. Subsequently, he attended Balliol College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, where he completed his DPhil in 1955. His doctoral thesis later became his book, The Death of Tragedy.

3. Career

George Steiner's career was marked by extensive academic appointments at prestigious institutions and prolific contributions as a literary critic and journalist, spanning half a century.

3.1. Academic Appointments

From 1956 to 1958, Steiner served as a scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He also held a Fulbright professorship in Innsbruck, Austria, from 1958 to 1959. In 1959, he was appointed Gauss Lecturer at Princeton, a position he held for two years. In 1961, he became a founding fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge.

Steiner initially faced a cool reception from the English faculty at Cambridge. Some faculty members disapproved of his charismatic and "foreign accent" and questioned the relevance of the Holocaust, which he frequently referenced in his lectures. Bryan Cheyette, a professor of 20th-century literature, noted that at the time, "Britain [...] didn't think it had a relationship to the Holocaust; its mythology of the war was rooted in the Blitz, Dunkirk, the Battle of Britain." Although Steiner received a professorial salary, he was never granted a full professorship at Cambridge with the right to examine. He considered offers for professorships in the United States, but his father objected, arguing that Hitler, who had vowed that no one bearing their name would remain in Europe, would then have "won." Steiner remained in England, stating, "I'd do anything rather than face such contempt from my father." He was elected an Extraordinary Fellow of Churchill College in 1969.

After several years as a freelance writer and occasional lecturer, Steiner accepted the position of Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Geneva in 1974. He held this post for 20 years, notably teaching in four languages, adhering to Goethe's maxim that "no monoglot truly knows his own language." Upon his retirement in 1994, he became professor emeritus at the University of Geneva. In 1995, he was made an Honorary Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. He also served as the first Lord Weidenfeld Professor of Comparative European Literature and Fellow of St Anne's College, Oxford, from 1994 to 1995, and as Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University from 2001 to 2002.

3.2. Literary Criticism and Journalism

Steiner was widely regarded as an "intelligent and intellectual critic and essayist." During his time at the University of Chicago, he was active in undergraduate publications. Later, he became a regular contributor of reviews and articles to numerous journals and newspapers, including The Times Literary Supplement and The Guardian. He wrote for The New Yorker for over thirty years, contributing more than two hundred reviews, a role he took over from Edmund Wilson in 1966. While Steiner generally approached his work with great seriousness, he also possessed a deadpan humor. When once asked if he had ever read anything trivial as a child, he famously replied, Moby-Dick.

4. Thought and Views

George Steiner's intellectual framework was characterized by his polymathic approach, his deep engagement with language and culture, and his often provocative ethical stances.

4.1. Key Intellectual Contributions

Steiner was considered a polymath and is frequently credited with reshaping the role of the critic by exploring art and thought without being confined by national borders or academic disciplines. He championed generalization over specialization, insisting that the concept of being literate must encompass knowledge of both the arts and sciences. Central to Steiner's thinking was his profound "astonishment, naïve as it seems to people, that you can use human speech both to love, to build, to forgive, and also to torture, to hate, to destroy and to annihilate." The enduring impact of the Holocaust was a pervasive theme in his work, as he stated, "My whole life has been about death, remembering and the Holocaust." His experience as a survivor profoundly influenced his perspective, leading him to describe himself as a "grateful wanderer" who owed his life to mobility. He also emphasized the significance of multilingualism, living by Goethe's maxim that "no monoglot truly knows his own language," and his theories on translation, particularly articulated in After Babel, were seminal contributions to the field of translation studies.

4.2. Cultural and Ethical Perspectives

Steiner held strong views on various cultural and ethical issues. He believed that nationalism was inherently too violent to satisfy the moral imperative of Judaism, asserting "that because of what we are, there are things we can't do." In his autobiography, Errata (1997), Steiner revealed a sympathetic stance towards the use of brothels since his college years at the University of Chicago, recounting a "gentle" and "caring" initiation that "blesses me still."

His views on racism garnered both criticism and support. Steiner controversially suggested that racism is inherent in everyone and that tolerance is merely superficial. He was quoted as saying, "It's very easy to sit here, in this room, and say 'racism is horrible'. But ask me the same thing if a Jamaican family moved next door with six children and they play reggae and rock music all day. Or if an estate agent comes to my house and tells me that because a Jamaican family has moved next door the value of my property has fallen through the floor. Ask me then!" In his critical work In Bluebeard's Castle (1971), Steiner proposed the controversial idea that Nazism was Europe's revenge on the Jews for inventing conscience. Literary critic Bryan Cheyette observed that Steiner's fiction served as "an exploratory space where he can think against himself," contrasting its humility and openness with his increasingly "closed and orthodox critical work." Cheyette also noted that central to Steiner's fiction was the survivor's "terrible, masochistic envy about not being there - having missed the rendezvous with hell."

5. Major Works

George Steiner's literary and critical output spanned half a century, addressing the complexities of contemporary Western culture, the debasement of language in the post-Holocaust era, and the fundamental nature of language and literature.

5.1. Key Books and Essays

Steiner's primary field was comparative literature, and his work as a critic often delved into cultural and philosophical issues, particularly concerning translation and the essence of language and literature.

His first published book was Tolstoy or Dostoevsky: An Essay in Contrast (1960), a study comparing the ideas and ideologies of the Russian literary giants Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Death of Tragedy (1961) originated from his doctoral thesis at the University of Oxford and offered an examination of literature from the ancient Greeks to the mid-20th century.

His most widely recognized work, After Babel (1975), was an early and highly influential contribution to the emerging field of translation studies. This work was later adapted for television as The Tongues of Men (1977) and notably inspired the formation of the English avant-rock group News from Babel in 1983.

Steiner's works of literary fiction include four short story collections: Anno Domini: Three Stories (1964), Proofs and Three Parables (1992), The Deeps of the Sea (1996), and A cinq heures de l'après-midiFive O'Clock in the AfternoonFrench (2008). His controversial novella, The Portage to San Cristobal of A.H. (1981), depicted Jewish Nazi hunters discovering Adolf Hitler (the "A.H." of the title) alive in the Amazon jungle three decades after World War II. This novella explored ideas about the origins of European anti-semitism that Steiner had first articulated in his critical work In Bluebeard's Castle (1971).

Other significant works include:

- Language and Silence: Essays 1958-1966 (1967)

- In Bluebeard's Castle: Some Notes Towards the Redefinition of Culture (1971)

- Extraterritorial (1971)

- The Sporting Scene: White Nights in Leningrad (1973), an account of the 1972 World Chess Championship match between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky.

- Heidegger (1978)

- On Difficulty (1978)

- Antigones (1984)

- Real Presences (1989)

- No Passion Spent (1996), a collection of essays on diverse subjects such as Kierkegaard, Homer in translation, Biblical texts, and Freud's dream theory.

- Errata: An Examined Life (1997), a semi-autobiography.

- Grammars of Creation (2001), based on his 1990 Gifford Lectures delivered at the University of Glasgow, which explores a range of subjects from cosmology to poetry.

- The Lesson of the Masters (2003)

- My Unwritten Books (2008)

- The New Yorker's George Steiner (2012), a collection of 28 reviews he contributed to the magazine over approximately 30 years.

- His final book, A Long Saturday: Conversations, was a collaboration with Laure Adler; it was published in French in 2014 and in English in 2017.

5.2. Themes and Literary Significance

Recurring themes throughout Steiner's oeuvre include translation studies, literary theory, cultural criticism, and the profound implications of the post-Holocaust condition. His work consistently challenged conventional boundaries between academic disciplines and national literatures, advocating for a holistic understanding of culture and the humanities. Steiner's unique perspective, shaped by his multilingual background and his family's escape from Nazi persecution, brought a deep ethical and philosophical dimension to his literary analysis, particularly in his explorations of language's capacity for both creation and destruction, and the moral responsibilities of intellectual inquiry in the modern age. His contributions significantly influenced comparative literature and cultural theory, establishing him as a leading voice in 20th and early 21st-century intellectual discourse.

6. Personal Life

George Steiner's personal life was closely intertwined with his intellectual pursuits, notably through his marriage and family.

6.1. Marriage and Family

Between 1952 and 1956, while teaching English at Williams College and working as a leader writer for the London-based weekly publication The Economist, Steiner met Zara Shakow. Zara was a New Yorker of Lithuanian descent who had also studied at Harvard. They met in London through a suggestion from their former professors, who had made a bet that they would marry if they ever met. George and Zara married in 1955, the same year he received his DPhil from Oxford University. They had two children: a son, David Steiner, who served as New York State's Commissioner of Education from 2009 to 2011, and a daughter, Deborah Steiner, who is a Professor of Classics at Columbia University. George Steiner last resided in Cambridge, England.

7. Death

George Steiner's prolific life concluded in early 2020.

7.1. Circumstances of Death

George Steiner died at his home in Cambridge, England, on February 3, 2020, at the age of 90. His wife, Zara Steiner, passed away from pneumonia ten days later.

8. Awards and Honors

George Steiner received numerous accolades and recognitions throughout his distinguished career, reflecting his significant contributions to academia, literature, and culture.

| Year | Award/Honor | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Rhodes Scholarship | |

| 1970/1971 | Guggenheim Fellowship | |

| 1974 | Remembrance Award | For Language and Silence: Essays 1958-1966 |

| 1984 | Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur | Awarded by the French Government |

| 1989 | Morton Dauwen Zabel Prize | From The American Academy of Arts and Letters |

| 1992 | PEN/Macmillan Silver Pen Award | For Proofs and Three Parables |

| 1993 | PEN/Macmillan Fiction Prize | For Proofs and Three Parables |

| 1995 | Honorary Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford | |

| 1997 | JQ Wingate Prize for Non-Fiction | Joint winner with Louise Kehoe and Silvia Rodgers for No Passion Spent |

| 1998 | Truman Capote Lifetime Achievement Award | From Stanford University |

| 1998 | Prix Aujourd'hui | French literary prize |

| 1998 | Fellowship of the British Academy | |

| 2001 | Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities | |

| 2001 | Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres | French cultural honor |

| N/A | King Albert Medal | From the Belgian Academy Council of Applied Sciences |

| N/A | Honorary Fellow of the Royal Academy of Arts |

He also received honorary Doctorate of Literature degrees from numerous universities:

- University of East Anglia (1976)

- University of Leuven (1980)

- Mount Holyoke College (1983)

- Bristol University (1989)

- University of Glasgow (1990)

- University of Liège (1990)

- University of Ulster (1993)

- Durham University (1995)

- University of Salamanca (2002)

- Queen Mary University of London (2006)

- Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna (2006)

- Honoris Causa - Faculty of Letters - University of Lisbon (2009)

9. Relationship with Japan

George Steiner had notable interactions and connections with Japan, contributing to academic and cultural exchange.

9.1. Visit to Japan and Academic Exchange

In April 1974, George Steiner visited Japan at the invitation of the Keio University's Mantaro Kubota Fund. During his visit, he delivered lectures and engaged in dialogues and debates with prominent Japanese intellectuals. These discussions included figures such as Shuichi Kato, Yasuya Takahashi, Masao Yamaguchi, and Jun Eto. His visit facilitated significant international scholarly engagement and exchange of ideas.

9.2. Publications in Japan

Following his visit, a collection of his lectures, dialogues, and essays about Steiner was published in Japan under the title 文学と人間の言語 日本におけるG.スタイナーBungaku to Ningen no Gengo Nihon ni okeru G. Sutainā (Literature and Human Language in Japan: G. Steiner)Japanese. This volume was published by Keio University's Mita Literary Library (now Keio University Press) in 1974. The editorial leadership for this publication was attributed to Yasaburo Ikeda, with substantial contributions from Shinsuke Ando and Kimiyoshi Yura. Many of Steiner's other works have also been translated into Japanese, making his ideas accessible to a Japanese-speaking audience.