1. Overview

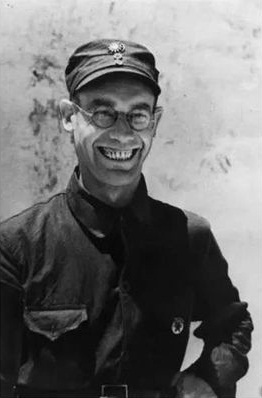

Otto Braun (Otto BraunGerman; 1900-1974) was a prominent German communist journalist and functionary whose career spanned several decades and continents. He is most widely recognized for his critical role as a Comintern agent dispatched to China in 1934, where he advised the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on military strategy during the Chinese Civil War. Operating under the Chinese name Li De (李德Lǐ DéChinese), Braun was the sole foreigner to participate in the arduous Long March and significantly influenced the early military campaigns of the Red Army. His strategic decisions, particularly his advocacy for conventional warfare against the numerically superior Kuomintang (KMT) forces, led to devastating losses for the CCP and ultimately sparked a pivotal shift in leadership at the Zunyi Conference, where Mao Zedong rose to prominence. After his time in China, Braun returned to the Soviet Union and later to East Germany, where he continued his work as a translator, editor, and writer, eventually publishing his influential memoirs, Chinese Notes. His life reflects a deep dedication to the revolutionary cause, yet his legacy remains a subject of historical debate, particularly concerning the effectiveness and human cost of his military advice in China.

2. Early Life and Education

Otto Braun was born on September 28, 1900, in Ismaning, Upper Bavaria, near Munich, Germany. Despite his mother being alive, he was raised in an orphanage from the age of six until thirteen.

2.1. Birth and Childhood

Braun's early life was marked by his upbringing in an orphanage, which shaped his formative years.

2.2. Education

He enrolled at a teachers' training college in Pasing, an area within Munich, in 1913. In June 1918, he was drafted into the ranks of the Bavarian Army, which was part of the Imperial German Army during World War I. However, the war concluded before he could be deployed to combat duty. Following the armistice, he returned to complete his studies at the teachers' training college, obtaining his teaching certificate in 1919. Despite qualifying as a primary school teacher, Braun chose not to pursue a career in education. Instead, he secretly joined the newly-founded Communist Party of Germany (KPD), having previously joined the Spartacus League, a precursor to the KPD, in 1917. He was also involved in the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. Embarking on a lifelong vocation in the communist movement.

3. Communist Activity in Germany

Braun's involvement with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) began early in his life, leading to various roles within the party and significant legal challenges.

3.1. Early Activities and Legal Issues

By 1921, Otto Braun had become a full-time, paid worker for the KPD. He was implicated in the theft of sensitive documents from Colonel Freyberg, a White Russian emigrant based in Berlin. In July 1921, Braun was detained by the police for his involvement in the incident. During his trial, he successfully concealed his communist affiliations, convincing the court that he was a "right-winger," which resulted in a lighter sentence due to the perceived bias in the Weimar Republic's judicial system. He avoided jail at that time and went into hiding. By 1924, Braun had become a core member of the KPD apparatus, regularly contributing articles to party newspapers and, after 1924, leading the party's "counter-espionage" efforts. He was also deeply involved in the party's militia and paramilitary activities. The police apprehended him again in September 1926. He first served his 1922 "Freyberg sentence" and was subsequently held in detention at Moabit Prison in Berlin.

3.2. Jailbreak and Exile to Moscow

On April 11, 1928, a group of communists, including his then-lover Olga Benário, orchestrated a daring jailbreak, freeing Braun from Moabit Prison. This audacious escape garnered worldwide publicity. Following their escape, Braun and Benário made their way to Moscow, Soviet Union, where they became deeply involved with the Communist International (Comintern).

4. Training in Moscow

Upon arriving in Moscow, Otto Braun and Olga Benário both enrolled at the International Lenin School, an institution operated by the Comintern for the training of international revolutionaries. Braun further pursued military education at the Frunze Military Academy, a prestigious Soviet military institution. While Braun was undergoing military training, Benário worked as an instructor at the Communist Youth International, initially in the Soviet Union, and later in France and England, where she coordinated anti-fascist activities. Braun and Benário eventually separated in 1931. Olga Benário went on to marry the renowned Brazilian revolutionary leader Luís Carlos Prestes and moved to Brazil. She was later arrested by the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship and extradited to Nazi Germany, where she was tragically killed in the gas chamber at the Bernburg Euthanasia Centre. She is widely remembered as a martyr by left-wing movements in both Brazil and Germany.

5. Activities in China

After completing his training in Moscow, Otto Braun was dispatched to China by the Comintern, where he played a controversial yet significant role within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

5.1. Dispatch to China and Early Work

In 1932, following his graduation from the Frunze Military Academy, the Fourth Directorate of Soviet Military Intelligence dispatched Braun to Harbin in Manchuria, China, at the request of Wang Ming. From Harbin, he traveled to Shanghai, where he joined the local Comintern bureau. In Shanghai, he worked under "General Kleber" (the nom de guerre of Manfred Stern) on military affairs, and under fellow German Communist Arthur Ewert on political issues. While some accounts suggest he was merely one of several advisors and not a direct representative of the Soviet Union, his influence was undeniable. However, Shanghai had become a challenging environment for the Chinese revolutionary movement after the Kuomintang (KMT) effectively crushed the local communist presence during the Shanghai massacre of 1927. Consequently, the CCP had retreated to the countryside, establishing their base in Jiangxi Province. In late 1933, Braun arrived in Ruijin, which served as the capital of the "Chinese Soviet Republic" established by the surviving Chinese Communists. There, he assumed the role of a military advisor. During his time in China, Braun adopted the Chinese name Li De (李德Lǐ DéChinese), and was also known as Litrof or Huafu (華夫HuáfūChinese). The exact circumstances of his appointment and his activities in the following years remain subjects of debate among historians, with his own memoirs, Chinese Notes, considered an important but "dubious" source.

5.2. Military Advisor and Strategy during the Civil War

In Ruijin, Otto Braun, alongside CCP General Secretary Bo Gu, exerted significant influence within the party. Bo Gu, who was only 26 at the time and had been appointed to lead the CCP Central Bureau with Comintern backing due to his Soviet study experience, was militarily inexperienced. Consequently, he granted Braun full authority over the military operations of the Red Army. From 1933 to 1934, Braun directly commanded these operations. During this period, the Kuomintang, led by Chiang Kai-shek, launched its Fifth Encirclement Campaign against the Chinese Soviet Republic, advised by German military consultant Hans von Seeckt. Braun, despite his limited practical military experience, advocated for conventional, positional warfare against the numerically superior and better-equipped KMT forces, rejecting Mao Zedong's preferred guerrilla warfare tactics. This strategy led to catastrophic losses for the Red Army, with its forces drastically reduced from approximately 86,000 to about 25,000 within a year. As Ruijin became untenable due to the KMT's advance, the CCP was forced to abandon its base and embark on the Long March in October 1934. Braun later claimed in his memoirs that he was merely an advisor without actual command authority and therefore not responsible for the defeat and withdrawal from Ruijin.

5.3. The Long March and the Zunyi Conference

Otto Braun, under his assumed name Li De, was the only foreigner to participate in the arduous Long March. Some historical accounts suggest he might have even been the original proposer of the idea to undertake such a march to reach safer interior regions of China. In late 1934, Braun, along with Zhou Enlai and Bo Gu, held a position of command within the early First Front Army, with authority over military decisions. However, during the Long March, particularly upon reaching Lipin, Braun and Zhou Enlai reportedly had fierce disagreements over strategy.

In January 1935, the CCP convened the Zunyi Conference in Guizhou Province. At this critical meeting, Mao Zedong and Peng Dehuai openly expressed their strong opposition to the military tactics employed by Braun and Bo Gu. Mao argued that Braun's direct attacks were causing excessive casualties and proposed that the smaller, less-equipped Red Army should instead utilize the guerrilla tactics for which Mao would become famous, focusing on evasion and surrounding the enemy. Mao had a long-standing distrust of European advisors from the Comintern, recalling past instances where advice from figures like the Dutch Henk Sneevliet had proven disastrous for the CCP in the 1920s. Other military leaders within the CCP agreed with Mao's assessment. Consequently, Braun and Bo Gu were relieved of their military command roles, and Mao Zedong emerged as the undisputed leader of the Long March. Following this conference, the influence of the Comintern within the CCP waned significantly, and "Native Communists" gained control of the party's direction.

Despite losing his military command, Braun remained in China until 1939 and continued to participate in the Long March alongside the CCP. His role shifted primarily to advisory work and teaching military tactics. By 1936, he was no longer invited to major party meetings, and he frequently requested permission from Moscow to return to the Soviet Union. However, he was not under house arrest and often hosted foreign and domestic supporters of the communist cause who arrived in Yan'an.

5.4. Personal Life in China

During his time in China, Otto Braun's personal life also saw significant changes. In 1933, he married Xiao Yuehua, a Chinese communist party member, though some accounts suggest she was more of a mistress than a wife. They had a son, but their marriage later ended in divorce when Braun developed a relationship with Li Lilian, a Chinese actress and fellow Communist Party member, whom he married in 1938. In Ruijin, Braun lived in a separate house with his interpreter, Wu Xiujuan, along with Wang Zhitao, security guards, a cook, and a stableman. He was noted for his preference for bread over traditional Chinese steamed buns (饅頭MántouChinese). Wu Xiujuan's later memoirs provided detailed, though sometimes exaggerated, accounts of Braun's life in Ruijin, including perceptions of a luxurious lifestyle and controversial personal choices, which stood out in the resource-scarce environment. Mao Zedong, in particular, viewed Braun as an "eyesore" due to his influence and perceived arrogance. In Yan'an, where the male-to-female ratio was significantly skewed (reportedly 18 males to 1 female), Braun's ability to marry Li Lilian was seen as a considerable advantage. On August 28, 1939, Braun departed for the Soviet Union. He attempted to bring his wife, Li Lilian, with him, but she was denied an entry permit. Zhou Enlai promised to send her later, but this never materialized, and Braun never saw Li Lilian again. Despite his departure, Braun maintained an interest in Chinese affairs for the remainder of his life.

6. Period in the Soviet Union and East Germany

After his departure from China, Otto Braun spent a significant period in the Soviet Union before eventually returning to East Germany, where he continued his work as a writer and public figure.

6.1. Activities in the Soviet Union

Braun arrived in the Soviet Union in 1939. This was a particularly perilous time for foreign communists in the USSR, as many, including German communists, faced imprisonment, torture, or execution by Joseph Stalin's secret police, the NKVD, despite their unwavering loyalty to the revolutionary cause. Braun, however, managed to avoid such a fate, although he encountered some political difficulties immediately upon his arrival. He found employment as an editor and translator at the Moscow Foreign Languages Press. He also became a member of the Free Germany National Committee until 1946, serving as a political instructor in various prisoner-of-war camps. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, his German background was utilized: he was appointed a "polit-instrukteur" (political instructor) tasked with influencing the loyalty of German officers captured by the Soviets. In this role, he used an old alias from the 1920s, "Kommissar Wagner." He later performed a similar role for captured Japanese officers. Between 1946 and 1948, Braun was based in Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast, where he lectured at the Antifascist Central School. He then had another period working at the Moscow Foreign Languages Press, and from 1951, he became a freelance writer. In 1945, he entered Berlin with the Soviet army.

6.2. Return to East Germany and Later Career

It was only after the death of Stalin in 1953 that Otto Braun was permitted to return to his homeland, after nearly three decades of exile. He arrived in the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) in 1954. There, Braun became a fellow at the Institute for Marxism-Leninism, which was maintained by the Central Committee of the ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), the official communist party of East Germany. His primary responsibility involved the publication of Vladimir Lenin's and Mikhail Sholokhov's writings in German, though few of these translations were ultimately published. From 1961 to 1963, he served as the First Secretary of the German Writers' Association under Erwin Strittmatter, after which he experienced a period of disfavor. Already in his mid-sixties, he became a pensioner, undertaking freelance translation work from Russian. His return to official favor became evident in 1964 when Neues Deutschland, the ruling party's official organ, published the revelation that the previously unknown Li De, a figure involved in the Chinese Long March of the 1930s, was in fact Otto Braun. During the Sino-Soviet split between 1959 and 1964, Braun frequently published articles criticizing China. His contributions and loyalty were recognized with several honors, including the Patriotic Order of Merit in 1967, the National Prize of the German Democratic Republic in 1969, and both the Karl Marx Order and the Lenin Medal in 1970 for his merits during World War II.

6.3. Writings and Memoirs

The public revelation of his identity in 1964 provided Braun with the opportunity and motivation to write his memoirs, Chinese Notes. These memoirs, titled Chinesische Aufzeichnungen (1932-1939) (Chinese Records), were written in the late 1960s while Braun was also a fellow at the Institute for Social Sciences. They were published in book form in 1973 and subsequently translated into Chinese, English (as A Comintern Agent in China 1932-1939), and other languages. The Japanese translation was titled The Inside Story of the Great Long March. His writings detail the bitter conflicts between Mao Zedong and the "International Faction" led by Wang Ming during the Yan'an period of the CCP. While researchers acknowledge that these memoirs contain interesting and valuable information, particularly for offering a perspective different from official CCP historiography, they are also considered far from objective or impartial. For a long time, the book was completely banned in China, but in recent years, regulations have eased, and Chinese historians now frequently cite it as an important source for understanding the early history of the Chinese Communist Party.

7. Death

Otto Braun died at the age of 74 on August 15, 1974, while on vacation in Varna, Bulgaria. He was buried in East Berlin, specifically at the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery. His death was publicly recognized with obituaries appearing in prominent newspapers such as Pravda (the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) and The New York Times.

8. Assessment and Legacy

Otto Braun's legacy is complex, marked by both his unwavering dedication to the communist movement and the significant controversies surrounding his strategic decisions, particularly during his tenure in China.

8.1. Positive Contributions

Braun was a dedicated communist revolutionary throughout his life. During his early period in China, from 1932 to 1933, he contributed to repelling attacks by Chiang Kai-shek's Kuomintang forces. He was the only foreigner to participate in the arduous Long March, a pivotal event in the history of the Chinese Communist Party. During the split of Zhang Guotao's army from the main communist forces in September 1935, Braun supported Mao Zedong's faction. His memoirs, Chinese Notes, are considered an important historical document, offering valuable insights into the early development of the CCP and the internal struggles between Mao Zedong and the Comintern-backed "International Faction." These writings provide a unique perspective that complements and sometimes challenges official Chinese historiography, making them a crucial resource for researchers studying the period.

8.2. Criticism and Controversy

Braun's time in China is often regarded as the most controversial part of his career. The precise circumstances of his appointment as a Comintern advisor and his activities in China remain debated, with his own memoirs acknowledged as a "dubious source" that is far from objective or impartial. His military strategies during the Chinese Civil War, particularly his insistence on conventional warfare against the numerically and technologically superior Kuomintang, led to "great casualties" and a drastic reduction in the Red Army's strength. This approach was heavily criticized by Chinese Communist leaders like Mao Zedong and Peng Dehuai, who advocated for guerrilla tactics better suited to their forces' capabilities. The disastrous outcome of his strategies ultimately led to his removal from military command at the Zunyi Conference. Accounts from his interpreter, Wu Xiujuan, and other Chinese sources, often portray Braun critically, highlighting his perceived arrogance, lack of understanding of Chinese conditions, and a somewhat luxurious lifestyle in resource-scarce environments like Ruijin. Mao Zedong reportedly viewed Braun as an "eyesore" due to his influence and the negative impact of his military advice. The controversies surrounding his decisions and their human cost continue to be a significant part of his historical assessment.