1. Overview

Konstantin von Neurath was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany from 1932 to 1938 and later as the first Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia from 1939 to 1943. Born into a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his diplomatic career in 1901, serving in various European capitals before his appointment as Foreign Minister. In the early years of the Nazi regime, he played a crucial role in legitimizing Adolf Hitler's aggressive foreign policy, which systematically undermined the Treaty of Versailles and facilitated Germany's territorial expansion in the prelude to World War II.

Despite his tactical reservations about Hitler's more radical war plans, Neurath's continued service and his later role as Reichsprotektor of the occupied Czech lands cemented his complicity in the regime's crimes. As Reichsprotektor, he implemented harsh policies, including censorship, suppression of dissent, and the persecution of Czechs and Jews, although his authority was later diminished due to perceived leniency. After World War II, Neurath was prosecuted at the Nuremberg trials as a major war criminal. He was found guilty on all four counts, including conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, and was sentenced to 15 years in prison. He was released in 1954 due to ill health and died two years later. His career is critically viewed as an example of how a traditional diplomat became an instrument of a totalitarian regime, contributing to severe human rights abuses and the erosion of international peace.

2. Early Life and Background

Konstantin von Neurath's early life was shaped by his aristocratic lineage and a strong tradition of public service within his family.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Konstantin Hermann Karl von Neurath was born on February 2, 1873, at the manor of Kleinglattbach, which is now part of Vaihingen an der Enz in Württemberg, then a kingdom within the German Empire. He pursued higher education in law, studying at the University of Tübingen and the Humboldt University of Berlin, where he earned a doctorate. After graduating in 1897, he initially joined a local law firm in his hometown, laying the foundation for his future career in public service.

2.2. Family Background and Noble Status

Neurath was the scion of a Swabian Freiherren (baron) noble family, which had a long-standing political dynasty within the Kingdom of Württemberg. His grandfather, Constantin Franz von Neurath, had served as Foreign Minister under King Charles I of Württemberg, who reigned from 1864 to 1891. His father, Konstantin Sebastian von Neurath, who died in 1912, was a member of the Free Conservative Party in the German Reichstag and held the position of Chamberlain to King William II of Württemberg. This distinguished family background and noble status provided Konstantin von Neurath with significant social and political connections, which greatly influenced his early life and career prospects.

2.3. Early Diplomatic Career

In 1901, Neurath entered the civil service, beginning his career at the Foreign Office in Berlin. His first international posting came in 1903 when he was assigned to the German embassy in London. He served there initially as Vice-Consul and, from 1909, as Legationsrat (legation counsel). In 1904, following a visit by the Prince of Wales to the Kingdom of Württemberg, Neurath, serving as Lord Chamberlain to King William II, was honored as an Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order. His diplomatic career was significantly advanced by Secretary of State Alfred von Kiderlen-Waechter. In 1914, he was transferred to the embassy in Constantinople.

3. World War I Service

During World War I, Konstantin von Neurath served as an officer with an infantry regiment, specifically the Grenadier Regiment "Queen Olga" of the 26th Division, until 1916, when he was severely wounded. In December 1914, he was awarded the Iron Cross for his service. He returned to German diplomatic service in the Ottoman Empire between 1914 and 1916. During this period, he notably authored a memorandum to German consulates in the Ottoman Empire concerning the Armenian genocide. This document aimed to justify the actions of the Ottoman government while simultaneously attempting to portray the German government as protesting against the "excesses" of the genocide. In 1917, he temporarily left the diplomatic service to assume the role of head of the royal Württemberg government, succeeding his uncle Julius von Soden, and served King William II closely until 1918.

4. Diplomatic Career (Pre-Nazi Era)

After World War I, Konstantin von Neurath resumed his diplomatic career, serving in several prominent European capitals, which established his reputation as an experienced and traditional diplomat.

4.1. Minister to Denmark, Italy, and Britain

In 1919, with the approval of President Friedrich Ebert, Neurath returned to the diplomatic corps and was appointed Minister to Denmark, serving at the embassy in Copenhagen. From 1921 to 1930, he held the position of ambassador to Rome, representing Germany in Italy. During his tenure in Italy, he observed the rise of Italian fascism but remained largely unimpressed by it. Following the death of Chancellor Gustav Stresemann in 1929, Neurath was considered a strong candidate for the post of Foreign Minister in the cabinet of Chancellor Hermann Müller by President Paul von Hindenburg. However, his appointment ultimately did not materialize due to objections raised by the governing parties. In 1930, Neurath was transferred once again, this time to head the German embassy in London, where he served as ambassador to Great Britain until 1932.

5. Political Career under the Nazi Regime

Konstantin von Neurath's political career under the Nazi regime was characterized by his initial role in lending an air of legitimacy to Adolf Hitler's foreign policy, followed by his gradual loss of influence due to his perceived moderation and tactical objections to the regime's increasingly aggressive plans.

5.1. Foreign Minister

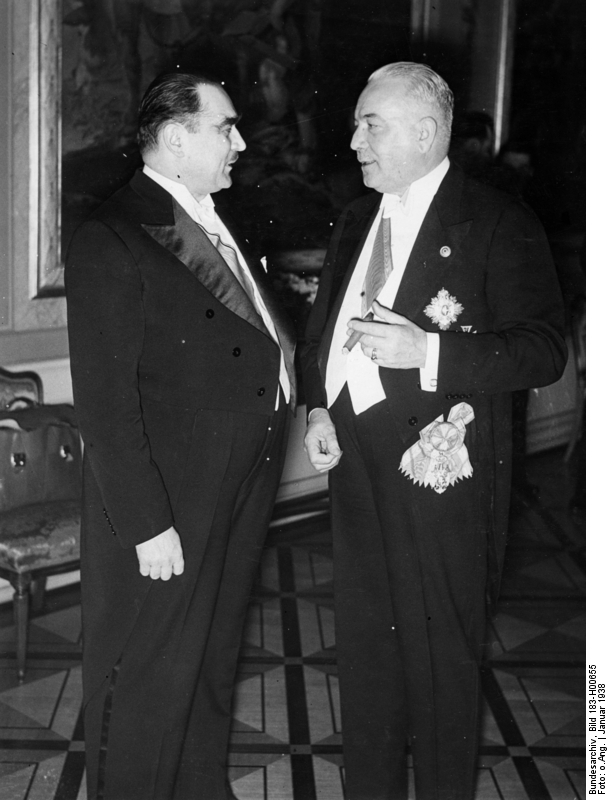

Neurath was recalled to Germany in 1932 and was appointed Reichsminister of Foreign Affairs as an independent politician within the "Cabinet of Barons" under Chancellor Franz von Papen in June. He retained this position under Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher in December and subsequently under Adolf Hitler following the Machtergreifung on January 30, 1933. In the early years of Hitler's rule, Neurath's presence, as a seasoned diplomat and a member of the nobility, provided an aura of respectability to Hitler's expansionist foreign policy on the international stage. In May 1933, an American chargé d'affaires noted that "Baron von Neurath has shown such a remarkable capacity for submitting to what in normal times could only be considered as affronts and indignities on the part of the Nazis, that it is still quite a possibility that the latter should be content to have him remain as a figurehead for some time yet."

Neurath was involved in key foreign policy initiatives of the early Nazi era. He facilitated Germany's withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933, participated in the negotiations for the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in 1935, and played a role in the diplomatic aftermath of the remilitarisation of the Rhineland in 1936. He was also made a member of Hans Frank's Academy for German Law. On January 30, 1937, to mark the fourth anniversary of the regime, Hitler decided to enroll all remaining non-Nazi ministers, including Neurath, into the Nazi Party and personally awarded them the Golden Party Badge. By accepting this, Neurath officially joined the Nazi Party (membership number 3,805,229). Furthermore, in September 1937, he was granted the honorary rank of an Gruppenführer in the SS, which was equivalent to a Generalleutnant (lieutenant general) in the Wehrmacht. On June 21, 1943, he was further promoted to the honorary rank of SS-Obergruppenführer, equivalent to a three-star general. On November 8, 1937, he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, Grand Cordon by Japan.

5.1.1. Role in Hitler's Foreign Policy

As Foreign Minister, Neurath was instrumental in implementing Hitler's initial foreign policy objectives, which aimed to dismantle the post-World War I international order. He played a significant role in Germany's decision to withdraw from the League of Nations on October 14, 1933, a move that signaled Germany's rejection of collective security and disarmament efforts. Following this, Hitler sought to conclude a non-aggression pact with Poland, and Neurath was tasked with these negotiations, resulting in the signing of a 10-year non-aggression treaty on January 26, 1934.

Neurath was also involved in the negotiations for the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in 1935, which allowed Germany to build a navy up to 35% of the size of the British fleet, effectively nullifying key naval restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles. Although Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler's private foreign policy advisor, increasingly overshadowed Neurath during these talks, Neurath's official position provided the necessary diplomatic facade. Furthermore, he managed the diplomatic fallout after the remilitarisation of the Rhineland on March 7, 1936, a direct violation of both the Treaty of Versailles and the Locarno Treaties, which further demonstrated Germany's disregard for international agreements.

5.1.2. Hossbach Memorandum and Opposition

On November 5, 1937, a pivotal conference took place between Hitler and his top military and foreign policy leaders, documented in the Hossbach Memorandum. During this meeting, Hitler explicitly outlined his plans for aggressive war, envisioning a series of localized conflicts in Central and Eastern Europe to secure Lebensraum (living space) and achieve autarky for Germany. He emphasized the urgency of these actions, stating that Germany must be prepared for war as early as 1938 and no later than 1943, before Western powers could gain an insurmountable lead in the arms race.

Neurath, along with War Minister Generalfeldmarschall Werner von Blomberg and Army Commander-in-Chief Generaloberst Werner von Fritsch, raised objections to Hitler's plans. Their concerns were primarily tactical rather than moral. They believed that any German aggression in Eastern Europe would inevitably trigger a war with France due to its alliance system, known as the cordon sanitaire. They further argued that such a conflict would quickly escalate into a broader European war, as Great Britain would almost certainly intervene rather than risk France's defeat. Moreover, they contended that Hitler's assumption that Britain and France would ignore these projected wars was flawed, given that these powers had begun their rearmament efforts later than Germany. Importantly, their opposition was not a moral stand against aggression or the annexation of Austria or Czechoslovakia, but rather a strategic assessment that Germany was not yet sufficiently rearmed for such a large-scale conflict and required more time.

5.2. Dismissal as Foreign Minister

In response to the reservations voiced at the Hossbach conference, Hitler moved to tighten his control over the military and foreign policy apparatus by removing those who had expressed doubts. On February 4, 1938, Konstantin von Neurath was dismissed as Foreign Minister, a decision that coincided with the removals of Blomberg and Fritsch in what became known as the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair. Neurath felt that his office had been marginalized and that his opposition to Hitler's aggressive war plans, based on his belief that Germany needed more time to rearm as detailed in the Hossbach Memorandum, had led to his dismissal.

He was succeeded by Joachim von Ribbentrop, a more fervent Nazi who was fully aligned with Hitler's expansionist vision. To mitigate any international concerns that his removal might cause, Neurath was retained in the government as a minister without portfolio. He was also nominally appointed president of the Secret Cabinet Council, which was presented as a super-cabinet designed to advise Hitler on foreign affairs. While this appeared to be a promotion on paper, the body existed only nominally and never actually convened. Hermann Göring later testified that the council "not for a minute." This effectively sidelined Neurath from any real influence over foreign policy.

6. Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia

Konstantin von Neurath's appointment as Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia marked a darker chapter in his career, as he became directly responsible for implementing Nazi policies in occupied territories, leading to significant human rights abuses.

6.1. Appointment and Role

In March 1939, Konstantin von Neurath was appointed Reichsprotektor of the occupied Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, serving as Hitler's personal representative in the territory. Hitler's decision to choose Neurath for this role was partly an attempt to pacify international outrage over the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. His initial responsibilities included governing the Protectorate and maintaining a semblance of order while integrating the region into the German Reich.

6.2. Rule and Persecution

Soon after his arrival at Prague Castle, Neurath began to implement strict Nazi policies. He instituted harsh press censorship and banned all political parties and trade unions, effectively suppressing any organized dissent. In October and November 1939, he ordered a severe crackdown on protesting students, which resulted in the imprisonment of 1,200 student protesters in concentration camps and the execution of nine of them. He also oversaw the systematic persecution of Czech Jews in accordance with the Nuremberg Laws, leading to widespread human rights violations and the systematic removal of Jews from public life and their eventual deportation. While these measures were undoubtedly draconian, Neurath's rule was considered relatively mild by Nazi standards, and he notably attempted to restrain the more extreme actions of his police chief, Karl Hermann Frank.

6.3. Loss of Authority

Despite his implementation of harsh measures, Hitler eventually deemed Neurath's rule to be too lenient. Consequently, in September 1941, Hitler effectively stripped him of his day-to-day powers. Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office, was appointed as his deputy. In reality, Heydrich, known for his extreme brutality, wielded the true power over the Protectorate, initiating a far more repressive regime. After Heydrich's assassination in 1942, Kurt Daluege succeeded him as acting Reichsprotektor, further diminishing Neurath's actual influence. Neurath officially remained as Reichsprotektor but his role became largely nominal. He attempted to resign in 1941, but his resignation was not accepted until August 1943, when he was formally succeeded by the former Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick. Towards the end of the war, Neurath reportedly had contacts with the German resistance.

7. Ideology and Party Affiliation

Konstantin von Neurath's political leanings were rooted in traditional German conservatism and diplomacy. Initially serving as an independent politician and a career diplomat from an aristocratic background, he did not initially align with the radical ideology of the Nazi Party. However, his acceptance of the Foreign Minister position under Adolf Hitler and his continued service within the Nazi government gradually implicated him in the regime's actions.

Despite his personal reservations regarding Hitler's more aggressive war plans, which were based on tactical rather than moral considerations, Neurath's presence in the cabinet provided a crucial veneer of legitimacy for the nascent Nazi regime on the international stage. He formally joined the Nazi Party on January 30, 1937, receiving the Golden Party Badge as a symbolic gesture from Hitler to integrate non-Nazi ministers. Furthermore, in September 1937, he was granted the honorary rank of Gruppenführer in the SS, equivalent to a Generalleutnant in the Wehrmacht. This honorary rank was later elevated to SS-Obergruppenführer on June 21, 1943. While he may not have been an fervent ideologue, his eventual party membership and SS ranks solidified his alignment with the regime's structure and its increasingly criminal activities, demonstrating his complicity through association and continued service.

8. Nuremberg Trials and Imprisonment

After World War II, Konstantin von Neurath was arrested by French forces and subsequently prosecuted by the Allies at the Nuremberg trials in 1946, facing charges as a major war criminal.

8.1. Trial and Guilty Verdict

Neurath was indicted on all four counts: "conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes and crimes against humanity". His defense, led by Otto von Lüdinghausen, attempted to argue that his successor, Joachim von Ribbentrop, bore greater responsibility for the atrocities committed by the Nazi state than Neurath did.

During his cross-examination on June 22, 1946, Neurath was questioned about Germany's unilateral abrogation of the Treaty of Versailles. He asserted that the treaty was unbearable for the German people and that he had advocated for its removal through peaceful means. Regarding the remilitarisation of the Rhineland in March 1936, he claimed it was not a violation of the treaty but a symbolic occupation with a single division, justified by the threat posed by the Franco-Soviet Mutual Assistance Treaty. When pressed on the Anschluss (annexation of Austria) in March 1938, he denied direct involvement, stating that Franz von Papen had made the decision in consultation with Hitler, bypassing him.

However, his testimony regarding his tenure as Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia proved more challenging. While Neurath claimed he had restrained Karl Hermann Frank's excesses, saved many Czechs from imprisonment, and even suggested to Hitler that Czechoslovakia should be granted independence, the British prosecutor, David Maxwell Fyfe, presented a damning report that Neurath had submitted to Hitler. This report advocated for the complete colonization of Czech lands, arguing that only Czechs racially compatible with Germans should remain, while others should be expelled or subjected to "special treatment." Neurath appeared flustered and initially claimed Frank had written it without his knowledge, but Fyfe then produced minutes of a meeting between Hitler, Neurath, and Frank, confirming Neurath's endorsement of the report's content. Unable to refute this, Neurath merely stated he had soon resigned and that all responsibility lay with his successor, Reinhard Heydrich. At the time of the trials, Neurath showed signs of early senile dementia, and his intelligence quotient (IQ) was measured at 125 in the Wechsler-Bellevue intelligence test administered by prison psychologist Gustav Gilbert.

The International Military Tribunal acknowledged that most of Neurath's crimes against humanity were committed during his relatively short tenure as the nominal Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, particularly in quelling the Czech resistance and in the summary execution of several university students. The tribunal concluded that Neurath had been a willing and active participant in war crimes. However, it also noted that he did not hold as prominent a position during the peak of the Third Reich's tyranny as some other defendants and was thus considered a "minor adherent" to the atrocities committed. He was found guilty by the Allies on all four counts and was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment. The judgment also considered mitigating factors, such as his interference with the Gestapo and Security Police to secure the release of many Czechs arrested after September 1, 1939, and many students arrested in the autumn of that year. It also noted Hitler's reprimand of Neurath in 1941 for his perceived leniency.

8.2. Imprisonment and Release

Konstantin von Neurath was held as a war criminal in Spandau Prison in Berlin from July 18, 1947, until November 1954. He was one of the seven war criminals sentenced to imprisonment at Nuremberg. According to the American prison director, Eugene K. Bird, Neurath made a polite and gentlemanly impression, always smiling even when speaking briefly. He was fond of chocolate and managed to obtain it secretly within the prison.

Neurath's health deteriorated significantly during his imprisonment. He eventually became unable to perform labor and developed aphasia. Prison doctors noted that it was dangerous for him to walk quickly and suggested that younger prisoners, such as Albert Speer or Baldur von Schirach, should support him when descending stairs. In July 1953, he suffered a severe heart attack, and on September 2, 1954, he experienced another critical heart attack, prompting preparations for his potential burial within the prison. However, his condition miraculously improved. The United States, United Kingdom, and France had long advocated for his early release due to his deteriorating health, but the Soviet Union had consistently opposed it. Following his second heart attack, the Soviet Union unexpectedly agreed to his release. Neurath was released on November 6, 1954, officially due to his ill health, in the wake of the London and Paris Conferences.

9. Personal Life

On May 30, 1901, Konstantin von Neurath married Marie Auguste Moser von Filseck (1875-1960) in Stuttgart. The couple had two children: a son named Konstantin, who was born in 1902, and a daughter named Winifred, born in 1904.

10. Death

After his early release from Spandau Prison in 1954, Konstantin von Neurath retired to his family's estates in Enzweihingen, West Germany. He died there two years later, on August 14, 1956, at the age of 83. His cause of death was an asthma attack.

11. Assessment and Impact

Konstantin von Neurath's life and career present a complex and controversial legacy, marked by his transition from a distinguished diplomat to a high-ranking official complicit in the crimes of the Nazi regime.

11.1. Historical Evaluation

Historically, Neurath is evaluated as a figure who bridged the gap between the traditional German diplomatic establishment and the radical foreign policy of Adolf Hitler. His long and respected career as a diplomat, serving in key European capitals like London and Rome, lent an initial veneer of international credibility to the nascent Nazi government. As Foreign Minister from 1932 to 1938, he played a central role in implementing Hitler's early foreign policy objectives, which systematically dismantled the Treaty of Versailles and paved the way for German expansionism. This included Germany's withdrawal from the League of Nations, the negotiation of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement, and the remilitarisation of the Rhineland. While his objections to Hitler's more aggressive war plans, as detailed in the Hossbach Memorandum, were rooted in tactical caution rather than moral opposition, his continued service and his formal integration into the Nazi Party and the SS underscored his complicity. His subsequent appointment as Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia further entangled him in the regime's oppressive machinery, even if his direct authority diminished over time. His conviction at the Nuremberg trials for conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity solidified his place in history as a participant in the Nazi regime's atrocities.

11.2. Criticism and Controversy

Konstantin von Neurath's actions and legacy are subject to significant criticism and controversy due to his profound complicity in the crimes of the Nazi regime. Despite his background as a traditional diplomat, he actively facilitated Hitler's aggressive foreign policy, which systematically undermined international agreements and contributed directly to the outbreak of World War II. His involvement in the withdrawal from the League of Nations and the remilitarization of the Rhineland were deliberate challenges to global peace and stability.

His tenure as Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia is particularly condemned. During this period, he implemented harsh administrative policies that directly impacted human rights and social control. These included severe press censorship, the banning of political parties and trade unions, and a brutal crackdown on student protests in October and November 1939, which resulted in the imprisonment of 1,200 students in concentration camps and the execution of nine. Furthermore, he oversaw the systematic persecution of Czechs and Jews in the Protectorate, enforcing the discriminatory Nuremberg Laws. While some sources note his perceived "leniency" by Nazi standards and his attempts to restrain figures like Karl Hermann Frank, these efforts were ultimately ineffective in preventing widespread oppression and suffering. The Nuremberg Tribunal's guilty verdict on all four counts, including crimes against humanity, unequivocally confirmed his responsibility for the regime's atrocities. Neurath's career serves as a stark historical warning about the dangers of technocratic complicity with authoritarian regimes and the devastating consequences for democracy, human rights, and vulnerable populations.