1. Overview

Mohammad Karim Khan Zand, born around 1705, was the founder of the Zand dynasty, ruling almost all of Iran (except for Khorasan) from 1751 until his death in 1779. During his reign, he also exercised control over some Caucasian territories and occupied the city of Basra for several years. Karim Khan is widely regarded as one of the most just and benevolent rulers in Iranian history. He earned the unique title of Vakil e-Ra'aayaa (وکیلالرعایاRepresentative of the PeoplePersian or Representative of the Subjects), preferring it over the traditional title of Shah, which he never officially adopted.

Under Karim Khan's leadership, Iran experienced a remarkable recovery from the devastation of over four decades of continuous warfare, marked by civil conflict and foreign invasions. His rule brought a renewed sense of tranquility, security, peace, and prosperity to the war-ravaged nation. The period from 1765 until his death in 1779 is often considered the zenith of Zand rule. During this time, diplomatic relations with Great Britain were successfully restored, and the East India Company was permitted to establish a trading post in southern Iran. Karim Khan established Shiraz as his capital, where he initiated extensive architectural projects and urban development to beautify and rebuild the city. Following his death, the country plunged back into civil war, and none of his descendants were able to maintain the stability and effective governance he had achieved, ultimately leading to the Zand dynasty's collapse and the rise of the Qajar dynasty under Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. Karim Khan Zand is remembered through numerous tales and anecdotes that depict him as a compassionate monarch deeply concerned with the welfare of his subjects, and his legacy remains highly positive in Iranian collective memory.

2. Early Life and Background

Karim Beg, later known as Karim Khan Zand, was born around 1705 in the village of Pari, which was then part of the Safavid Empire. He was the eldest son of Inaq Khan Zand and had three sisters, a brother named Mohammad Sadeq Khan, and two half-brothers, Zaki Khan and Eskandar Khan Zand.

He belonged to the Zand tribe, a small and lesser-known tribe of the Laks, themselves a branch of the Lurs. Some historical accounts suggest the Zands may have originally been of Kurdish descent, and some Kurdish nationalists, such as Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou, have considered Karim Khan a Kurdish hero. The Zand tribe was primarily concentrated in the villages of Pari and Kamazan within the Malayer district but also roamed in the central Zagros Mountains and the countryside surrounding Hamadan.

The early 18th century was a period of immense turmoil for Iran. In 1722, the Safavid Empire was on the brink of collapse, with its capital Isfahan and much of central and eastern Iran seized by the Afghan Hotaks. Simultaneously, the Russians had conquered several northern Iranian cities during the Russo-Persian War (1722-1723), while the Ottoman Empire exploited Iran's weakness to conquer numerous western frontier districts. However, the Ottomans faced fierce resistance from local clans, including the Zands, who, under their chief Mehdi Khan Zand, successfully harassed Ottoman forces and prevented their further advance into Iran.

In 1732, Nader Qoli Beg, who had effectively restored Safavid rule and become the de facto ruler of the country, led an expedition into the Zagros mountains to subdue various tribes he deemed bandits. He first defeated the Bakhtiari and Feylis, forcing many to mass-migrate to Khorasan. Nader then lured Mehdi Khan Zand and his forces out of their stronghold at Pari, resulting in the death of Mehdi Khan and 400 Zand kinsmen. The surviving members of the tribe, led by Inaq Khan Zand and his younger brother Budaq Khan Zand, were compelled to migrate to Abivard and Dargaz, where the able-bodied, including Karim Beg, were conscripted into Nader's army.

By 1736, Nader had deposed the Safavid ruler Abbas III and ascended the throne as "Nader Shah," establishing the Afsharid dynasty. Karim Beg, then in his thirties, served as a cavalryman in Nader's army but held a low status and faced financial hardship. A well-known anecdote from this period illustrates his character: as a poor cavalryman, he once stole a gold-embossed saddle left for repair outside a saddler's shop. Upon learning the saddler was to be executed for the loss, Karim, conscience-stricken, secretly returned the saddle. He observed from concealment as the saddler's wife discovered it, falling to her knees and blessing the unknown thief who had a change of heart, praying for him to live and own a hundred such saddles. This incident, often recounted, highlights his innate sense of justice and compassion even in his early, humble life.

3. Rise to Power

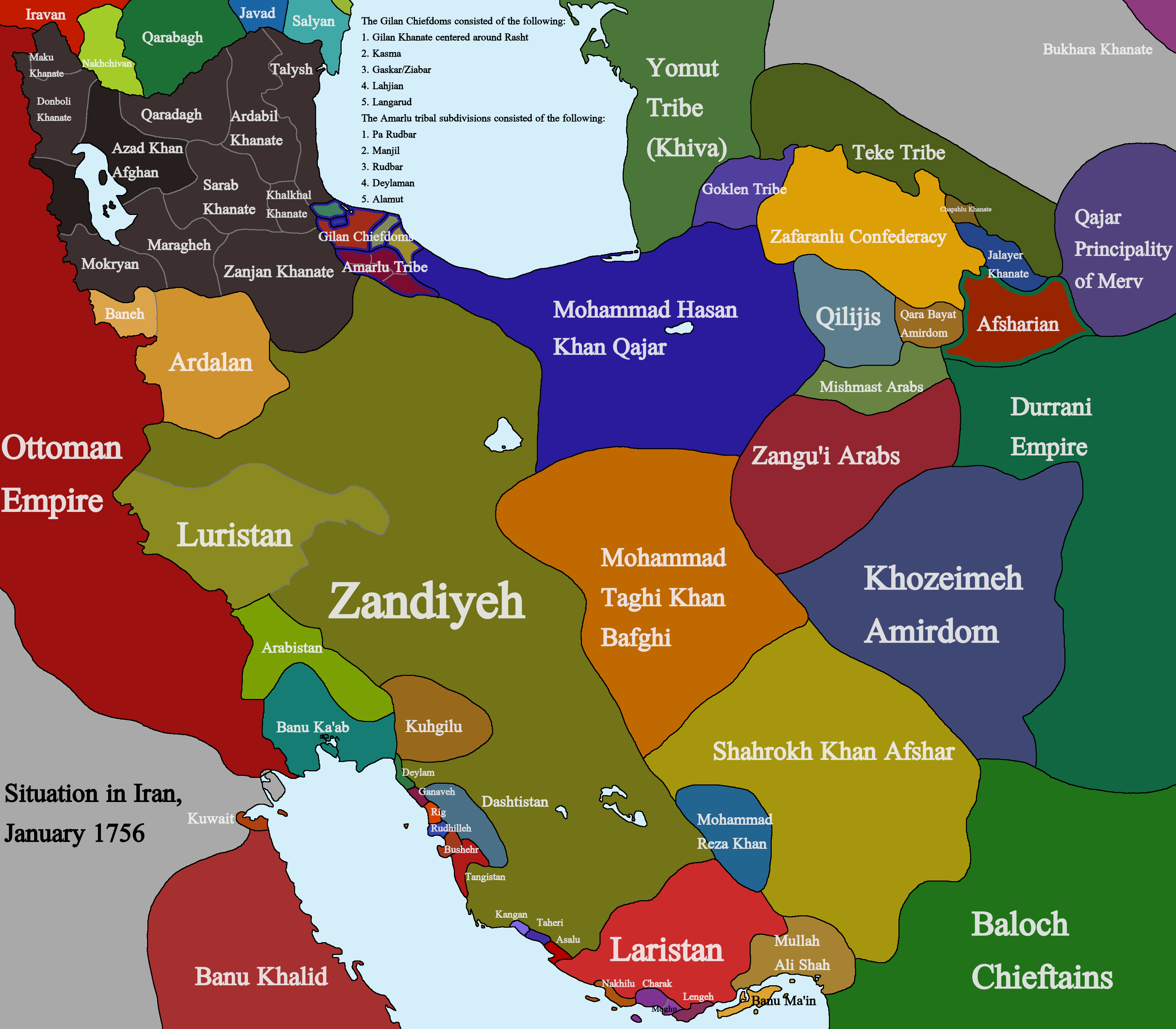

After Nader Shah's assassination in 1747, Iran plunged into a tumultuous period of civil war, creating an opportunity for the Zand tribe, under the leadership of Karim Khan, to return to their ancestral lands in western Iran.

3.1. Return to Western Iran and Early Alliances

In 1748 or 1749, Karim Khan forged an alliance with the military leader Zakariya Khan. They initially clashed with the powerful Bakhtiari chieftain Ali Mardan Khan Bakhtiari, whom they defeated in their first encounter. However, Karim Khan's forces soon suffered a setback and were compelled to withdraw from the strategically important town of Golpayegan, which Ali Mardan then seized.

In the spring of 1750, Ali Mardan attempted to capture the former Safavid capital, Isfahan, but was repelled at Murcheh Khvort, a town near the city. Following this defeat, he dispatched messengers from Golpayegan to his regional opponents, including Karim Khan and Zakariya Khan. Both leaders accepted Ali Mardan's terms, combining their forces to reach an impressive total of 20,000 men.

In May 1750, this allied force stormed the gates of Isfahan. Its governor, Abu'l-Fath Khan Bakhtiari, along with other prominent residents, initially gathered to defend the city's fortress. However, they agreed to surrender and collaborate after Ali Mardan presented reasonable proposals. Subsequently, Abu'l-Fath, Ali Mardan, and Karim Khan formed a tripartite alliance in western Iran, ostensibly to restore the Safavid dynasty. On June 29, a 17-year-old Safavid prince named Abu Turab was appointed as a puppet ruler, adopting the dynastic name of Ismail III and being declared shah.

Following this arrangement, Ali Mardan assumed the title of Vakil-e daulat (deputy of the state), effectively becoming the head of the administration. Abu'l-Fath retained his position as governor of Isfahan, while Karim Khan was appointed commander (sardar) of the army, entrusted with the crucial task of conquering the remaining parts of Iran. However, this alliance proved fragile. Just a few months later, while Karim Khan was on an expedition in Kurdistan, Ali Mardan began violating the terms of their agreement with the inhabitants of Isfahan. He dramatically increased his demands for tribute and imposed severe shake-downs on the city, with the Armenian quarter of New Julfa suffering the most. He further broke his agreements with the two chieftains by having Abu'l-Fath deposed and killed. Ali Mardan then appointed his own uncle as the new governor of Isfahan and, without consulting his allies, marched towards Shiraz, commencing the widespread pillaging of the Fars region. After plundering Kazerun, Ali Mardan began his return to Isfahan but was ambushed at the perilous passage of Kutal-e Dokhtar by local guerrillas led by Muzari Ali Khishti, the chieftain of the neighboring Khisht village. The guerrillas managed to seize Ali Mardan's plunder and killed 300 of his men, forcing him to withdraw to a more difficult passage to reach Isfahan. By winter, Ali Mardan's forces had further diminished due to desertions.

3.2. Consolidation of Power

The deteriorating situation for Ali Mardan worsened when Karim Khan returned to Isfahan in January 1751 and swiftly restored order in the city. A decisive battle between their forces soon erupted in Chaharmahal. During this engagement, Ismail III and Zakariya Khan, who was now serving as Ismail III's vizier, along with several prominent officers, deserted Ali Mardan and joined Karim Khan's side. Karim Khan ultimately emerged victorious, compelling Ali Mardan and the remnants of his forces, accompanied by the governor of Luristan, Ismail Khan Feyli, to retreat to Khuzestan.

In Khuzestan, Ali Mardan formed an alliance with Shaykh Sa'd, the local governor, who provided him with additional soldiers. In the late spring of 1752, Ali Mardan, joined by Ismail Khan Feyli, marched towards Kermanshah. Karim Khan's forces soon attacked their encampment but were repelled. Ali Mardan then advanced deeper into the Zand domains, leading to another confrontation with Karim Khan near Nahavand. However, Ali Mardan suffered yet another defeat and was forced to withdraw into the mountains, eventually seeking refuge in the Ottoman city of Baghdad.

A year later, in early 1753, Ali Mardan, along with a former Afsharid diplomat and a son of the deposed Safavid shah Tahmasp II, returned to Iran and began assembling an army in Luristan. They also secured the support of the Pashtun military leader Azad Khan Afghan. Months later, they marched into Karim Khan's territories. However, Tahmasp II's son, who had been proclaimed Sultan Husayn II, quickly revealed himself to be an unfit candidate for the Safavid throne. This hampered their advance and led to widespread desertion among their ranks.

Meanwhile, Ali Mardan's forces in Kirmanshah, after two years of siege by Zand troops, finally surrendered and were spared by Karim Khan. Karim Khan shortly clashed with Ali Mardan once more, defeating him and capturing Mustafa Khan. Although Ali Mardan managed to flee with Sultan Husayn II, he soon had the Safavid prince blinded and sent to Iraq, deeming him more of a burden than a useful ally. Through these strategic maneuvers and decisive military victories, Karim Khan established his supremacy and consolidated his control over most of Iran.

4. Reign

Karim Khan Zand's reign was characterized by a focus on domestic stability, economic recovery, and careful foreign policy, aimed at rebuilding Iran after decades of conflict. He chose the title Vakil e-Ra'aayaa (Representative of the People) instead of Shah, reflecting his genuine concern for the welfare of his subjects.

4.1. Domestic Policies and Administration

Karim Khan's approach to governance marked a distinct shift from his predecessors. He specifically avoided adopting the title of Shah, preferring to be known as Vakil e-Ra'aayaa (وکیلالرعایاRepresentative of the PeoplePersian). This choice underscored his dedication to the welfare of his subjects, a focus that became a hallmark of his rule. During his time in power, Iran experienced a significant recovery from 40 years of continuous warfare, leading to a period of remarkable tranquility, security, peace, and prosperity. The years between 1765 and his death in 1779 are widely considered the peak of Zand rule, marked by stability and flourishing conditions.

Karim Khan maintained a relatively small bureaucracy, a decision influenced both by his personal preference and the administrative chaos and collapse that had preceded his rule. Although he was supported by a vizier and a chief revenue officer (mustaufī), their actual influence and authority were minimal because Karim Khan rigorously managed political affairs himself.

Provincial administration under Karim Khan largely followed the model established by the Safavid dynasty. Provinces were governed by beglerbegis. Within cities, a kalantar and darugha held authority, while individual quarters were overseen by a kadkhuda. The governorships of provinces were largely entrusted to tribal chieftains from Fars and its surrounding areas. A minister, experienced in administration and tax collection, regularly accompanied each governor to ensure efficient management. Karim Khan also introduced two new official posts specifically to manage tribal affairs: an ilkhani was appointed as the paramount leader for all the Lur tribes, and an ilbegi was designated as the leader for all the Qashqai tribes roaming in Fars.

In terms of religious policy, Karim Khan diverged from the Safavids. Unlike the former dynasty, he did not actively seek the approval or validation of the ulama (clergy), who had previously served as crucial pillars of the shah's authority as viceroys of God and the Imams. This approach demonstrated his practical and secular-leaning governance, prioritizing administrative efficiency and public welfare over religious legitimization.

4.1.1. Military

Karim Khan maintained a formidable standing army during his reign, essential for securing internal stability and projecting power externally. His military was primarily composed of tribal contingents, reflecting the diverse ethnic groups within his domain. From 1765 to 1775, his standing army in Fars consisted of approximately 45,000 personnel, structured as follows:

| Troop Type | No. of personnel |

|---|---|

| Lur, Kurd (Laks, Feylis, Zand, Zanganeh, Kalhor, etc.; cavalry) | 24,000 |

| Bakhtiari (cavalry and tofangchi infantry) | 3,000 |

| Iraqi, i.e., from Persian Iraq (Persian tofangchi infantry) | 12,000 |

| Fars (including Khuzestan and Dashtestan: Persian tofangchi infantry, Arab and Iranian cavalry) | 6,000 |

| Total | 45,000 |

Following Karim Khan's death, his well-organized army unfortunately fragmented into various segments. These segments initially aligned with different Zand princes vying for the throne during the subsequent civil wars, but ultimately, the majority of the military contingents shifted their allegiance to the rising Qajar ruler, Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar.

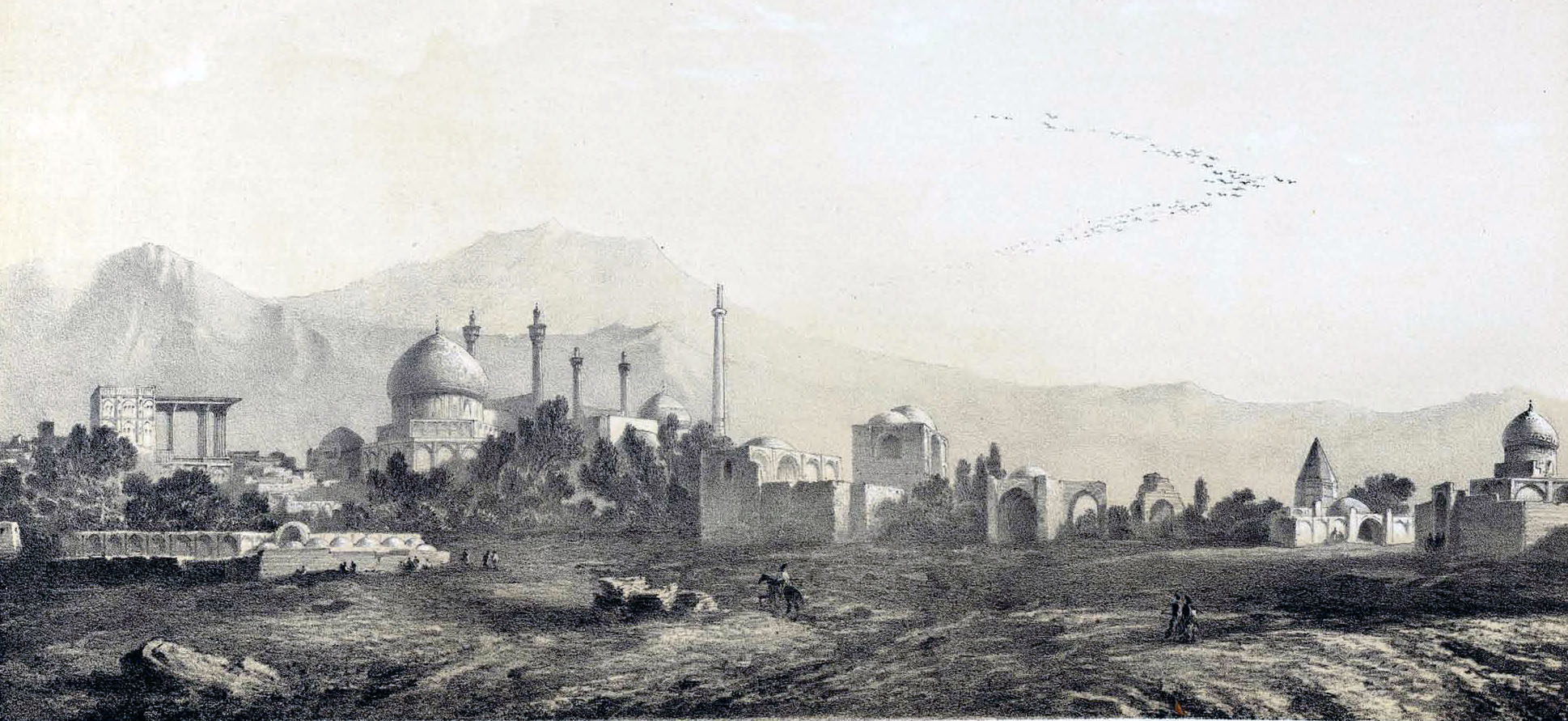

4.1.2. Construction

Karim Khan Zand embarked on an ambitious program of urban development and architectural construction, particularly in his chosen capital, Shiraz. He extensively rebuilt much of the city and ordered the erection of numerous new buildings, showcasing his commitment to restoring and beautifying Iran after years of conflict.

Among his most famous projects was the Arg of Karim Khan, a grand citadel that served as his royal residence. He also commissioned the construction of several gardens, mosques, a new city wall, various public baths, a caravanserai, and a prominent bazaar. Unfortunately, many of these structures were later destroyed, either during Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar's capture of Shiraz in 1792 or during the subsequent metropolitan restructuring in the 20th century.

Beyond new constructions, Karim Khan also undertook the renovation of the burial places of significant historical figures, including the prominent Muzaffarid ruler Shah Shoja Mozaffari (r. 1358-1384) and the celebrated Persian poets Hafez and Saadi.

His efforts also extended to social urban planning. Many pastoral Lur and Lak families were encouraged and assisted in settling and building homes in Shiraz. This initiative contributed significantly to the city's population growth, which reached an estimated 40,000 to 50,000, surpassing that of Isfahan. The revitalized and prosperous Shiraz attracted numerous poets, craftsmen, and even foreign traders from Europe and India, who were warmly received and contributed to the city's vibrant cultural and economic life.

4.2. Foreign Relations and Major Conflicts

During Karim Khan Zand's reign, Iran sought to re-establish its international standing and engage in diplomatic relations, notably restoring ties with Great Britain. He permitted the East India Company to establish a trading post in southern Iran, indicating a desire to promote commerce and stability. However, his rule was also marked by significant military engagements, including conflicts with the Dutch East India Company and the Ottoman Empire.

- War with the Dutch East India Company**

The Zand forces frequently clashed with the Dutch East India Company over influence and control of Kharg Island, an important strategic and trading point in the Persian Gulf. This ongoing tension reflected the broader competition for maritime trade routes and commercial dominance in the region.

- War with the Ottoman Empire (1775-1776)**

A major conflict during Karim Khan's rule was the war with the Ottoman Empire, which commenced in 1775 and lasted until 1776. The primary trigger for this war was the meddling of Omar Pasha, the Mamluk governor of the Ottoman province of Iraq, in the affairs of the vassal principality of Baban. Since the death of his predecessor Sulayman Abu Layla Pasha in 1762, Baban had increasingly fallen under the influence of the Zand governor of Ardalan, Khosrow Khan Bozorg. Omar Pasha exacerbated tensions by dismissing the Baban ruler, Muhammad Pasha, and appointing Abdolla Pasha as his successor.

Additional grievances fueled Karim Khan's decision to declare war. Omar Pasha had seized the remaining Iranian pilgrims who had died during a plague that ravaged Iraq in 1773. Furthermore, he exacted payments from Iranian pilgrims seeking to visit the holy Shia sites of Najaf and Karbala, which was deeply offensive to Karim Khan. Beyond these immediate causes, strategic and religious considerations also played a role. The holy Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad was not under Zand control, making free access to the sanctuaries in Iraq of greater significance to Karim Khan than it had been to previous Safavid and Afsharid shahs. The Zand army was also discontent, seeking to restore its reputation following Zaki Khan's humiliating blunders on Hormuz Island. Most importantly, Basra, a prominent trading port, had surpassed the competing city of Bushehr in Fars by 1769, after the East India Company had shifted its operations from Bushehr to Basra, making its control economically vital for the Zands.

The Zand forces, led by Ali-Morad Khan Zand and Nazar Ali Khan Zand, initially engaged Pasha's forces in Kurdistan, holding them at bay. Concurrently, Sadeq Khan, commanding an army of 30,000, laid siege to Basra in April 1775. The Arab tribe of al-Muntafiq, allied with the governor of Basra, quickly withdrew without attempting to prevent Sadeq Khan from crossing the Shatt al-Arab. Meanwhile, the Banu Ka'b and Arab communities from Bushehr provided Sadeq Khan with vital boats and supplies, facilitating his siege efforts.

Suleiman Agha, the commander of the Basra fort, fiercely resisted Sadeq Khan's forces, compelling the latter to establish a comprehensive encirclement that would last for over a year. During the siege, Henry Moore, representing the East India Company, attempted to hinder Sadeq Khan's operations by assaulting some of his stockpile boats and trying to blockade the Shatt al-Arab before departing for Bombay. A few months later, in October, a fleet of ships from Oman provided supplies and military aid to Basra, significantly boosting the morale of its defenders. However, their subsequent combined attack proved indecisive, and the Omani ships eventually chose to withdraw back to Muscat during the winter to avoid further losses.

Reinforcements from Baghdad arrived shortly afterward, but these were repelled by the Khaza'il, a Shia Arab tribe allied with the Zand forces. By the spring of 1776, Sadeq Khan's relentless encirclement had pushed the defenders of Basra to the brink of famine. A significant portion of the Basra forces deserted Suleiman Agha, and rumors of a potential uprising within the city further weakened his position, leading Suleiman Agha to surrender on April 16, 1776.

Despite the fact that the capable Ottoman Sultan Mustafa III (r. 1757-1774) had died and was succeeded by his less competent brother Abdul Hamid I (r. 1774-1789), and notwithstanding the recent Ottoman defeat to the Russians, the Ottoman response to the Ottoman-Iranian war was notably slow. In February 1775, even before news of the Basra siege reached Istanbul, and while the Zagros Mountains front was temporarily peaceful, the Ottoman ambassador, Vehbi Efendi, was sent to Shiraz. He arrived around the same time Sadeq Khan began besieging Basra but had not been granted authority to negotiate regarding this new crisis, leading to further delays in a diplomatic resolution.

In 1778, Karim Khan had engaged in discussions with the Russians for a cooperative offensive into eastern Anatolia. However, this planned invasion never materialized due to Karim Khan's death on March 1, 1779.

5. Personal Life and Relations with Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar

Mohammad Karim Khan Zand maintained a notably unusual and benevolent relationship with Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, who would later found the Qajar dynasty and ultimately overthrow the Zands. Agha Mohammad Khan had been brought to Shiraz as a virtual hostage, but Karim Khan treated him with remarkable kindness and honor, far from the typical treatment of a captive.

During his stay in Shiraz, Agha Mohammad Khan was not merely confined; Karim Khan actively sought his counsel on matters of state, acknowledging his political acumen. He even referred to Agha Mohammad Khan as his "Piran-e Viseh," a reference to the intelligent counselor of the legendary Iranian king Afrasiab, highlighting the respect Karim Khan held for his insights.

Karim Khan had successfully persuaded Agha Mohammad Khan's kinsmen to lay down their arms, after which he settled them in Damghan. In 1763, Agha Mohammad Khan himself, along with his brother Hosayn Qoli Khan, was sent to the Zand capital, Shiraz, where their paternal aunt, Khadijeh Begum, resided as part of Karim Khan's harem. Agha Mohammad Khan's half-brothers, Morteza Qoli Khan and Mostafa Qoli Khan, were granted permission to live in Astarabad, as their mother was the sister of the city's governor. His remaining brothers were sent to Qazvin, where they were also treated honorably. Two of Agha Mohammad Khan's brothers who had been in Qazvin were later also sent to Shiraz during this period, further consolidating the Qajar family's presence, albeit under Zand oversight.

In February 1769, Karim Khan appointed Hosayn Qoli Khan as the governor of Damghan. Upon reaching Damghan, Hosayn Qoli Khan immediately engaged in fierce conflicts with the Develu and other local tribes, seeking to avenge his father's death. However, he was killed around 1777 near Findarisk by some Turks from the Yamut tribe with whom he had clashed.

The unusual relationship between Karim Khan and Agha Mohammad Khan persisted until Karim Khan's death. On March 1, 1779, while Agha Mohammad Khan was out hunting, he received the news from Khadijeh Begum that Karim Khan had died after six months of illness. This moment proved pivotal, as Agha Mohammad Khan immediately fled Shiraz to pursue his own claim to power.

6. Death

Mohammad Karim Khan Zand died on March 1, 1779. He had been ill for approximately six months leading up to his death, with the suspected cause being tuberculosis. Three days after his passing, on March 4, 1779, he was interred in the "Nazar Garden" in Shiraz, which is now known as the Pars Museum. His death marked a significant turning point for Iran, ending a period of relative peace and stability.

7. Succession and Post-Death Instability

Karim Khan's death on March 1, 1779, immediately plunged Iran back into intense civil war, a stark contrast to the period of stability he had fostered. The Zand dynasty, which he had meticulously built, quickly fractured as various princes and claimants vied for power.

One faction, led by Zaki Khan in alliance with Ali-Morad Khan Zand, declared Karim Khan's youngest and arguably least capable son, Mohammad Ali Khan Zand, as the new Zand ruler. Simultaneously, another influential group, including Shaykh Ali Khan and Nazar Ali Khan, along with other prominent notables, rallied behind Karim Khan's elder son, Abol-Fath Khan Zand.

However, Zaki Khan, known for his ruthless tactics, soon lured Shaykh Ali Khan and Nazar Ali Khan out of the fortress of Shiraz and had them brutally slaughtered. This act of violence further destabilized the already fragile succession. None of Karim Khan's descendants or immediate successors proved capable of ruling the country with the same effectiveness or maintaining the cohesion that he had. The civil war that followed his death saw the Zand army, which had been unified under Karim Khan, disintegrate into several segments. These segments initially joined the various Zand princes fighting for the throne, but ultimately, the majority of the forces shifted their allegiance to the rising power of the Qajar dynasty under Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar.

The internal struggles and infighting among the Zand princes significantly weakened the dynasty, making it vulnerable to external threats. The last prominent descendant of Karim Khan, Lotf Ali Khan, valiantly attempted to restore Zand authority but was ultimately defeated and executed by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. This final act marked the complete collapse of the Zand dynasty and led to Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar becoming the sole ruler of Iran, subsequently founding the Qajar dynasty.

8. Legacy and Assessment

Mohammad Karim Khan Zand holds a unique and highly regarded position in Iranian history, particularly for his efforts to restore stability and prosperity after decades of turmoil.

8.1. Character and Benevolent Rule

Karim Khan is consistently praised for his generosity, modesty, and fairness, often to a greater extent than many other Iranian rulers. Historians and popular accounts frequently present him as a benevolent monarch with a sincere and deep interest in the welfare of his subjects, surpassing even figures like Khosrow I Anushirvan and Shah Abbas I the Great in terms of his compassionate governance, although these monarchs might exceed him in military fame and global reputation.

A wealth of tales and anecdotes depict Karim Khan as a genuinely compassionate ruler, truly concerned with the well-being of his people. Even in contemporary Iran, he is widely remembered by his compatriots as a respectable man who, despite rising to power, maintained his virtuous character. He was never ashamed of his modest origins and never attempted to fabricate a more distinguished lineage than that of a leader from a formerly little-known tribe that roamed the Zagros Mountains of western Iran.

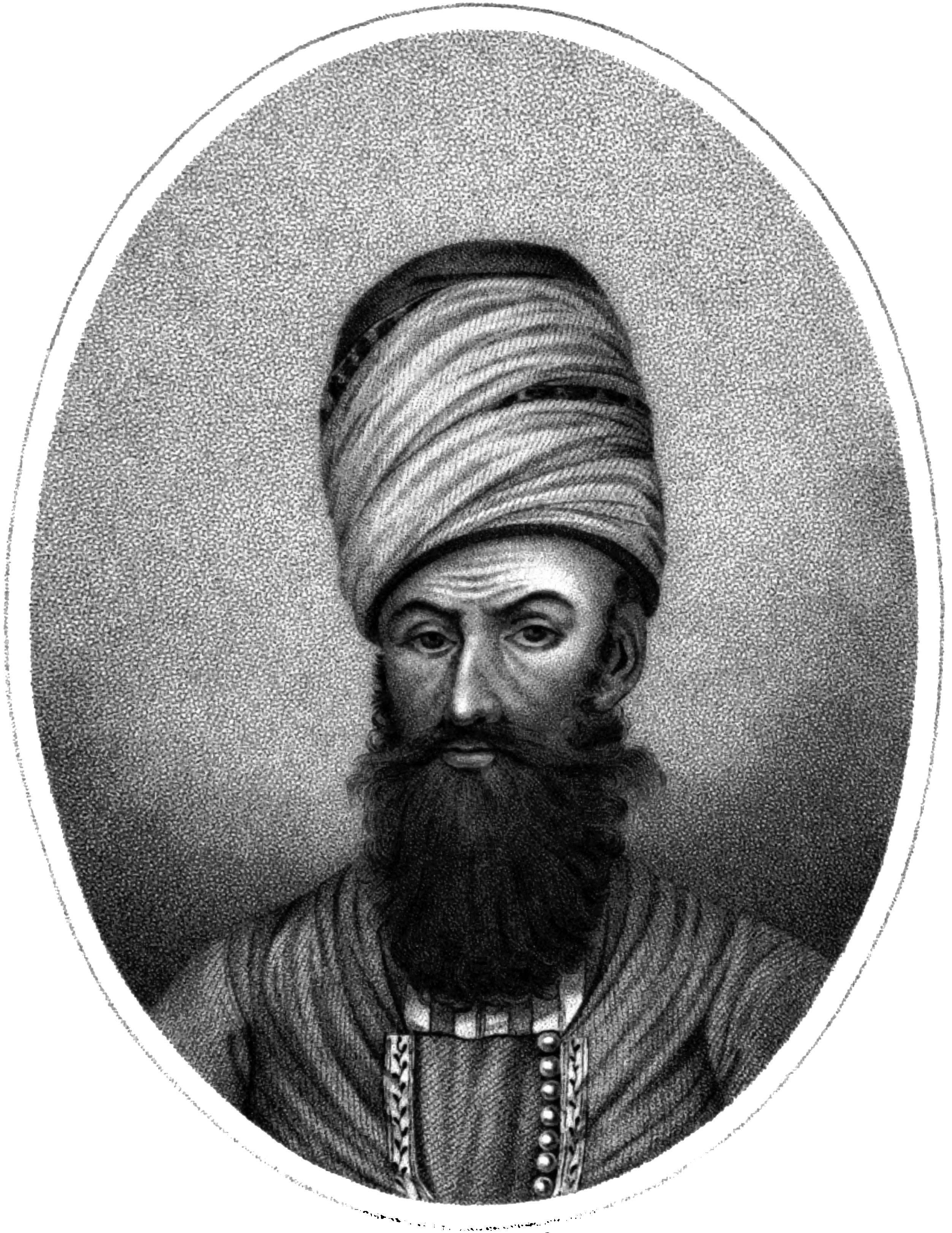

His personal preferences reflected his modesty: he favored simple clothes and furniture, often wearing a tall yellow cashmere Zand turban and sitting on an inexpensive carpet rather than an elaborate throne. He was known for having valuable jewels crushed into pieces and sold to stabilize the state treasury, demonstrating his commitment to fiscal responsibility over personal luxury. An interesting anecdote even highlights his unique personal habits, noting that he washed himself and changed clothes only once a month, a frugality that surprised even his own kinsmen.

8.2. Historical Impact and Enduring Legacy

During his reign, Karim Khan remarkably succeeded in fostering an unexpected degree of good fortune and harmony in a country that had suffered immense damage and turmoil under his predecessors. Although his integrity and positive image are considerably magnified when contrasted with the cruelty and authoritarianism of rulers like Nader Shah and Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar, his unusual blend of vitality, ambition, rationality, and goodwill created, for a brief but significant period in a notably fierce and anarchic century, a balanced and virtuous state.

According to The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, Karim Khan Zand holds an "enduring reputation as the most humane Iranian ruler of the Islamic era." His lasting positive image is so strong that following the Islamic Revolution of 1979, when the names of past rulers became taboo and many street names associated with the monarchy were changed, the citizens of Shiraz steadfastly refused to rename two main streets: Karim Khan Zand Street and Lotf Ali Khan Zand Street, demonstrating the deep respect and affection for his legacy.

The historian John Malcolm succinctly summarized Karim Khan's reign: "The happy reign of this excellent prince, as contrasted with those who preceded and followed him, affords the historian of Persia that kind of mixed pleasure and repose, which a traveler enjoys on arriving in a beautiful and fertile valley during an arduous journey over barren and rugged wastes. It is pleasing to recount the actions of a chief who, though born of an inferior rank, obtained power without crime, and who exercised it with a moderation that, for the times in which he lived, was as singular as his humanity and justice." This enduring praise underscores Karim Khan's significant contributions to the recovery and stabilization of Iran after decades of warfare, highlighting his role in fostering tranquility, security, peace, and prosperity that left a lasting positive impact on Iranian collective memory and culture.

9. In Art

Mohammad Karim Khan Zand has been immortalized in various artistic works, reflecting his significant cultural presence beyond mere historical accounts. Notably, he is the central character of a melodrama titled L'assedio di Sciraz (The siege of Shiraz), composed by the Italian musician Nicolò Gabrielli. This work first premiered at the prestigious La Scala theatre in Milan during Carnival in 1840, showcasing Karim Khan's story to a European audience.