1. Overview

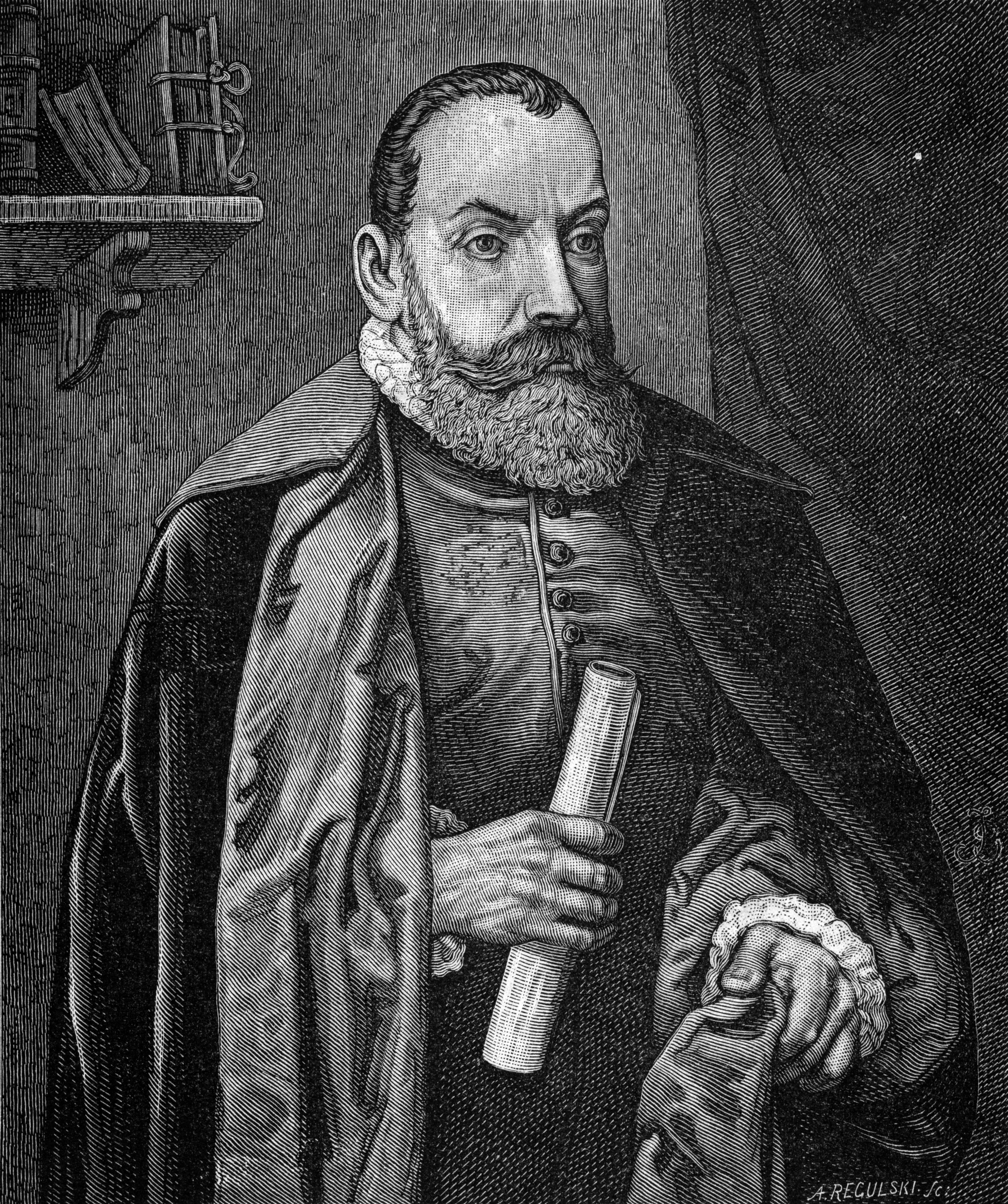

Jan Kochanowski (Jan KochanowskiPolish, Ioannes CochanoviusLatin; 1530 - 22 August 1584) was a preeminent Polish Renaissance poet and royal secretary who wrote extensively in both Latin and Polish. He is widely recognized for his pivotal role in shaping the Polish literary language and establishing poetic patterns that became fundamental to Polish literature. Often hailed as the greatest Polish poet before Adam Mickiewicz and one of the most influential Slavic poets prior to the 19th century, Kochanowski's contributions laid the groundwork for modern Polish verse forms and greatly enriched the national literary tradition.

His early life included extensive studies at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, the University of Königsberg, and the University of Padua in Italy, where he engaged with leading humanist scholars. He also traveled to France, meeting figures like Pierre de Ronsard. Upon his return to Poland, he served as a royal secretary to King Sigismund II Augustus, participating in significant political events such as the Union of Lublin. In 1569, he was present at the Sejm of 1569 in Lublin, which enacted the Union of Lublin, formally establishing the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Later, he retired to his family estate in Czarnolas, where he led the life of a country squire and produced some of his most profound works.

Kochanowski's literary output is vast and diverse, encompassing elegies, epigrams, odes, and the first tragedy written in Polish. His most celebrated works include the witty collection of short poems, Fraszki (Epigrams); the pioneering tragedy The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys (Odprawa posłów greckichPolish); and the deeply moving series of nineteen elegies, Treny (Laments), written in response to the death of his young daughter, Urszula. His translation of the Psalms, David's Psalter (Psalterz DawidówPolish), became a lasting part of Polish religious and cultural life. Kochanowski's work is characterized by its technical mastery, modern linguistic approach, and a unique blend of classical humanism with deep Christian faith. His enduring legacy is reflected in his continued study, numerous artistic adaptations, and the establishment of a museum dedicated to him at Czarnolas.

2. Early Life and Education

Jan Kochanowski's formative years were marked by a noble family background and an extensive, international education that deeply influenced his intellectual and poetic development.

2.1. Birth and Family

Jan Kochanowski was born in 1530 at Sycyna, a village near Radom, in the Kingdom of Poland. While his exact birth date remains unknown, his tombstone in Zwoleń, which states he died on 22 August 1584 at the age of 54, suggests his birth year was 1530. An alternative biography from 1612 indicates he was born in 1532. However, modern Polish literary historians, such as Janusz Pelc, consider 1530 to be the most reliable date.

He belonged to the Polish noble family, the szlachta, bearing the Korwin coat of arms. His father, Piotr Kochanowski, was a relatively wealthy landowner who served as the first bailiff (komornikPolish) of Radom and later as a judge in the Sandomierz area. His mother, Anna Białaczowska, hailed from the Odrowąż family. Jan was the second son among eleven siblings, including brothers Kasper, Piotr, Mikołaj, Andrzej, Jakub, and Stanisław, and sisters Katarzyna, Elżbieta, Anna, and Jadwiga. He also had half-siblings, Druzjanna and Stanisław, from his father's previous marriage to Zofia, daughter of Jan Zasada. His father, Piotr, died in 1547. The highly intellectual environment within his parents' home is believed to have significantly influenced Jan and his younger brothers, Mikołaj and Andrzej, who also became notable poets and translators. Mikołaj was a Renaissance poet, and Andrzej was known for his Polish translation of Virgil's Aeneid. Later, during the Baroque period, their nephew Piotr also engaged in translation work, further cementing the family's literary inclination.

2.2. Education and Travels

Little is known about Jan Kochanowski's earliest education. His name first appears in historical records in 1544, when he enrolled at the Kraków Academy (now Jagiellonian University) at the age of fourteen. Researchers speculate that he left the Faculty of Arts by 1547 without obtaining a degree, possibly due to the suspension of lectures on 12 June 1547 because of a plague epidemic, or due to his father's deteriorating health, who died that year.

Between 1547 and 1550, Kochanowski is believed to have studied at a German university or resided in the household of a prominent aristocrat. From 1551 to 1552, he attended the University of Königsberg in Ducal Prussia, which was a fiefdom of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The only surviving evidence of his presence there is two annotations in a copy of Seneca's "Tragedies." The first is a Latin quatrain, his earliest poetic attempt, dedicated to his friend Stanisław Grzepski (later a Jagiellonian University professor known for his geometry textbook), signed "I.K." and dated 9 April 1552. The second is a cryptic note, likely a code understood between Kochanowski and Grzepski. This copy is now held at the National Library in Warsaw.

A Latin dedication in his writings signaled his departure for Italy in 1552. He arrived in Padua, Italy, where his name is recorded in the student register of the University of Padua. He initially studied in the Faculty of Arts until 1555, even serving as an advisor for Polish university unions in July 1554, discussing independence issues with impoverished German students. He interrupted his studies around 1555 to travel to Rome and Naples with his friends Jan Krzysztof Tarnowski and Mikołaj Mielecki (a future military figure and politician), before returning to Poland. This interruption was likely due to financial difficulties and the need to secure patronage. He traveled back and forth between Italy and Poland at least twice during this period to obtain funding and attend his mother's funeral.

From 1555 to 1556, Kochanowski stayed at the residence of Duke Albert of Prussia in Königsberg. Duke Albert, a descendant of the Jagiellonian dynasty through his mother, who was the daughter of Sigismund I of Poland, acted as a patron to the Polish poet. The Duchy of Prussia, a vassal of the religiously tolerant Polish Kingdom, was a Lutheran state. Although Kochanowski did not receive payment in 1555 due to the conservative attitude of the household treasurer, he received 50 grzywna (a historical unit of weight, approximately 7.1 oz (200 g), also used as currency) in 1556. Surviving letters to his patron include one from 6 April 1556, where Kochanowski tearfully expressed his desire to travel to Italy to return to university, citing an eye condition. Duke Albert consented in a reply dated 15 April, granting him an additional 50 grzywna as a farewell gift.

To secure further travel funds, Kochanowski visited his family estate from Königsberg. On 16 July 1556, having returned from Italy, he declared in Radom County that he had borrowed 70 Polish florins from his distant relative Mikołaj Kochanowski, using his parents' land as collateral. On 11 March 1557, he submitted a promissory note to the court for 100 Hungarian ducats borrowed from his brother Piotr.

His subsequent journey to Italy was accompanied by Piotr Kłoczkowski (later Castellan of Zawichost). The poet likely visited Abano Terme, a spa town near Padua. His stay in Italy continued until February 1557, when he returned home upon receiving news of his mother's death. Kochanowski's final trip to Italy was in the winter of 1558, departing for France by the end of that year. The only surviving evidence of this journey is an elegy written in the form of a letter, which suggests he visited Marseille and Paris and traveled through Aquitaine in southwestern France, observing the Loire River, Rhône River, and Seine River. It is believed that the Flemish humanist Karel Utenhove (the younger) guided Kochanowski during his French travels. In May 1559, Kochanowski returned to Poland permanently.

3. Royal Service and Career

Upon his permanent return to Poland, Kochanowski embarked on a distinguished career that saw him deeply embedded in the country's humanist circles and royal court, culminating in significant public appointments.

3.1. Return to Poland and Court Life

In 1559, Jan Kochanowski permanently returned to Poland, where he quickly became an active figure as a humanist and a Renaissance poet. The period between 1559 and 1563 is not well-documented, but it is presumed that he established close contacts with the court of Jan Tarnowski, the Voivode of Kraków, and the influential Radziwiłł family. Legal documents indicate that on 11 July 1559, his parents' estate was divided among the siblings. Jan Kochanowski inherited half of Czarnolas, Ruda, a mill, a fish pond along the Grodzka River, and other appurtenances. The other half of Czarnolas went to his uncle Filip. His siblings, however, required him to pay 400 Polish florins in compensation. On 25 March 1560, Jan and Filip reached an agreement to lease the inherited property to their relatives for a total of 400 Polish florins, which Kochanowski used to pay off his debts to his siblings. A dispute between his uncle and his son-in-law was brought before the Royal Court of Parliament in Piotrków on 12 December 1562.

During this period, Kochanowski resided in various noble households, including those of Tarnowski, Tęczyński, Jan Firlej (a nobleman and Calvinist activist), and Filip Padniewski, the Bishop of Kraków.

3.2. Royal Secretary

Around mid-1563, Kochanowski entered the service of Piotr Myszkowski, the Vice Chancellor of the Crown and Bishop. Thanks to Myszkowski's support, Kochanowski received the title of royal secretary. While specific details of his duties at the royal court are scarce, his works from this period often reflect his engagement in political affairs, indicating his role in expressing the views of the royal court to members of the Sejm (parliament) and voters, effectively serving as a journalistic commentator before the advent of formal journalism.

Kochanowski served King Sigismund II Augustus until 1572. In 1567, he accompanied the King during a military demonstration near Radashkovichy (near Minsk) as part of the Lithuanian-Muscovite War, itself a component of the Livonian War. He also contributed significantly to the preparations for the 1568 Moscow expedition. In 1569, he was present at the Sejm of 1569 in Lublin, a momentous event that formally established the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by uniting Poland and Lithuania. Kochanowski commemorated this significant event, specifically the oath of allegiance sworn by Duke Albert Frederick of Prussia to Sigismund II, in his poem Proporzec albo hołd pruskiPolish (The Banner, or the Prussian Homage).

3.3. Benefices and Public Office

Through Piotr Myszkowski's influence, Kochanowski also acquired ecclesiastical benefices, which were incomes from parishes. On 7 February 1564, he was appointed provost of Poznań Cathedral, a position Myszkowski had previously held and renounced. He also obtained the rectory in Zwoleń.

After the death of Sigismund II Augustus, Kochanowski supported Henry of Valois's candidacy for the Polish throne, participating in the election in 1573 and attending his coronation at Wawel Cathedral in 1574. However, following Henry's sudden departure from Poland, Kochanowski largely withdrew from active court life. Although he later supported Stephen Báthory, he did not return to permanent royal service. He participated in the electoral parliament and benefited from the patronage of Jan Zamoyski, the royal secretary. The wars led by Stephen Báthory inspired several victory odes and the long poem Jezda do MoskwyPolish (Moscow Travel Journal), which described Duke Krzysztof Radziwiłł Piorun's daring expedition into Russia during the Polish-Russian War.

Despite urgings from close associates like Jan Zamoyski, Kochanowski chose not to actively participate in court politics. Nevertheless, he remained socially engaged at a local level, frequently visiting Sandomierz, the capital of his voivodeship. On 9 October 1579, King Stephen Báthory signed Kochanowski's nomination as the standard-bearer of Sandomierz in Vilnius. His connections with powerful magnate families such as the Tarnowskis, Tęczyńskis, Firlejs, and Radziwiłłs also remained significant throughout this period.

4. Later Life and Private Life in Czarnolas

The final decades of Jan Kochanowski's life were marked by a shift from public service to a more private existence on his family estate, where he focused on his family and literary endeavors.

4.1. Marriage and Family

From 1571 onward, Kochanowski began to spend increasing amounts of time at his family estate in the village of Czarnolas, located near Lublin. In 1574, following the departure of Poland's recently elected King Henry of Valois (whose candidacy Kochanowski had supported), he settled permanently in Czarnolas to embrace the life of a country squire.

In 1575, he married Dorota Podlodowska, daughter of Sejm deputy Stanisław Lupa Podlodowski, from Przytyk, bearing the Janina coat of arms. Together, they had seven children: six daughters and one son. The profound personal impact of his daughter Urszula's death, at the tender age of two and a half, deeply affected him and inspired one of his most memorable and enduring works, Treny (Laments).

4.2. Life as a Landowner

While living in Czarnolas, Kochanowski embraced the life of a landowner. In July 1575, he participated in the szlachta assembly in Stężyca, where the election of a new monarch was discussed. In November of the same year, at the electoral Sejm in Warsaw, he delivered a speech advocating for Maximilian II of the House of Habsburg as a candidate for the Polish throne.

Despite his retirement from active court politics, Kochanowski remained involved in local affairs and was a frequent visitor to Sandomierz, the capital of his voivodeship. This period of his life in Czarnolas was highly productive, witnessing the creation of his play The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys and his acclaimed translation of the Psalms, David's Psalter, published in 1579. His most famous work, Treny, a cycle of nineteen elegies written in 1579, was a direct expression of his grief and despair over the loss of his beloved daughter, Urszula. In 1583, he also penned Jezda do MoskwyPolish (Moscow Travel Journal), a long poem dedicated to Krzysztof Radziwiłł Piorun, describing his bold expedition into Russia during the Polish-Russian War under Stephen Báthory.

5. Major Literary Works

Jan Kochanowski's literary output is a cornerstone of Polish Renaissance literature, encompassing a wide range of genres and demonstrating his mastery of both Latin and Polish. His works are celebrated for their thematic depth, stylistic innovation, and lasting cultural impact.

5.1. Early Works and Latin Poetry

Kochanowski's earliest known work is likely the Polish-language Pieśń o potopiePolish (Song of the Deluge), possibly composed as early as 1550. His first published work was the 1558 Latin-language Epitaphium CretcoviiLatin, an epitaph dedicated to his recently deceased colleague Erazm Kretkowski. Works from his youthful Padua period primarily consist of elegies, epigrams, and odes, showcasing his early poetic voice and deep engagement with classical influences.

Upon his permanent return to Poland in 1559, Kochanowski's works generally shifted towards epic poetry. These included commemorative pieces such as O śmierci Jana Tarnowskiego, kasztelana krakowskiego, do syna jego, Jana KrisztofaPolish (On the Death of Jan Tarnowski, Castellan of Kraków, to his son, Jan Krzysztof, 1561) and Pamiątka wszytkimi cnotami hojnie obdarzonemu Janowi Baptiście hrabi na TęczyniePolish (Remembrance for the All-Blessed Jan Baptist, Count at Tęczyn, 1562-64). More serious works included ZuzannaPolish (1562) and Proporzec albo hołd pruskiPolish (The Banner, or the Prussian Homage, 1564). He also produced satirical social and political commentary poems like ZgodaPolish (Accord, or Harmony, ca. 1562) and Satyr albo Dziki MążPolish (The Satyr, or the Wild Man, 1564). His light-hearted works included Szachy (Chess, ca. 1562-66), described as the first Polish-language "humorous epic or heroicomic poem." Some of his works from the 1560s and 1570s can be seen as journalistic commentaries, expressing the views of the royal court and targeting members of parliament (the Sejm) and voters.

5.2. Fraszki (Epigrams)

Kochanowski's Fraszki (Epigrams, FraszkiPolish), a collection of 294 short poems, were composed during the 1560s and 1570s and published in three volumes in 1584. These witty and varied poems, reminiscent of Giovanni Boccaccio's The Decameron, became Kochanowski's most popular writings and inspired numerous imitators in Poland. The Polish Nobel laureate poet Czesław Miłosz described them as a "very personal diary, but one where the personality of the author never appears in the foreground." The collection covers a wide range of themes, from personal observations and everyday life to philosophical reflections and social commentary, showcasing Kochanowski's versatility and keen wit.

5.3. Treny (Laments)

The Treny (Laments, TrenyPolish), composed during the 1560s and 1570s and published in three volumes in 1584, represent a profound and innovative series of nineteen elegies. These poignant poems mourn the tragic loss of Kochanowski's beloved two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Urszula. The Laments are considered a pinnacle of Kochanowski's poetic art, achieving a unique place in world literature by applying a classical form to a deeply personal sorrow, particularly for a subject as "insignificant" (by contemporary standards) as a young child. This innovation scandalized some contemporaries but cemented its lasting impact. The Laments have been translated into English multiple times, including by Dorothea Prall in 1920, and by the acclaimed duo Stanisław Barańczak and Seamus Heaney in 1995. This work became a perennially popular wellspring for a new genre in Polish literature, expressing the poet's grief and despair with unparalleled emotional depth.

5.4. Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys)

Odprawa posłów greckich (The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys, Odprawa posłów greckichPolish), written around 1565-66 and first published and performed in 1578, is a pioneering blank-verse tragedy. Modeled after Homer, the play recounts an incident leading to the Trojan War. It holds significant historical and literary importance as the first tragedy written in Polish. Its central theme, the responsibilities of statesmanship and the consequences of moral decay in leadership, remains relevant to this day. The play premiered on 12 January 1578 at Ujazdów Castle in Warsaw, performed at the wedding of Jan Zamoyski and Krystyna Radziwiłł, both of whom were important patrons of Kochanowski. Czesław Miłosz praised it as "the finest specimen of Polish humanist drama." It was also the first book to be printed in Warsaw.

5.5. Songs (Pieśni) and David's Psalter (Psalterz Dawidów)

Kochanowski's Pieśni (Songs, Pieśni Jana Kochanowskiego księgi dwojePolish), written throughout his lifetime and published posthumously in 1586 in two volumes, reflect Italian lyricism and his deep attachment to antiquity, particularly to the Roman poet Horace. These lyrical poems have been highly influential for subsequent Polish poetry.

His translation of the Psalms, Psalterz Dawidów (David's Psalter, Psałterz DawidówPolish), published in 1579, was a free and influential rendition of the Old Testament's Book of Psalms. By the mid-18th century, at least 25 editions of this work had been published. Set to music, it became an enduring and integral element of Polish church masses and popular culture. It also gained significant international influence, being translated into Russian by Symeon of Polotsk, and into Romanian, German, Lithuanian, Czech, and Slovak.

5.6. Other Polish Poems and Prose

Kochanowski's extensive creative output includes other notable Polish works. The non-poetic political commentary dialogue, WróżkiPolish (Portents), further showcases his engagement with contemporary issues. Among works published posthumously, the historical treatise O Czechu i Lechu historyja naganionaPolish (Woven Story of Czech and Lech) offered the first critical literary analysis of Slavic myths, focusing on the titular origin myth about Lech, Czech, and Rus. In some of his works, Kochanowski utilized Polish alexandrines, a verse form where each line comprises thirteen syllables with a caesura following the seventh syllable.

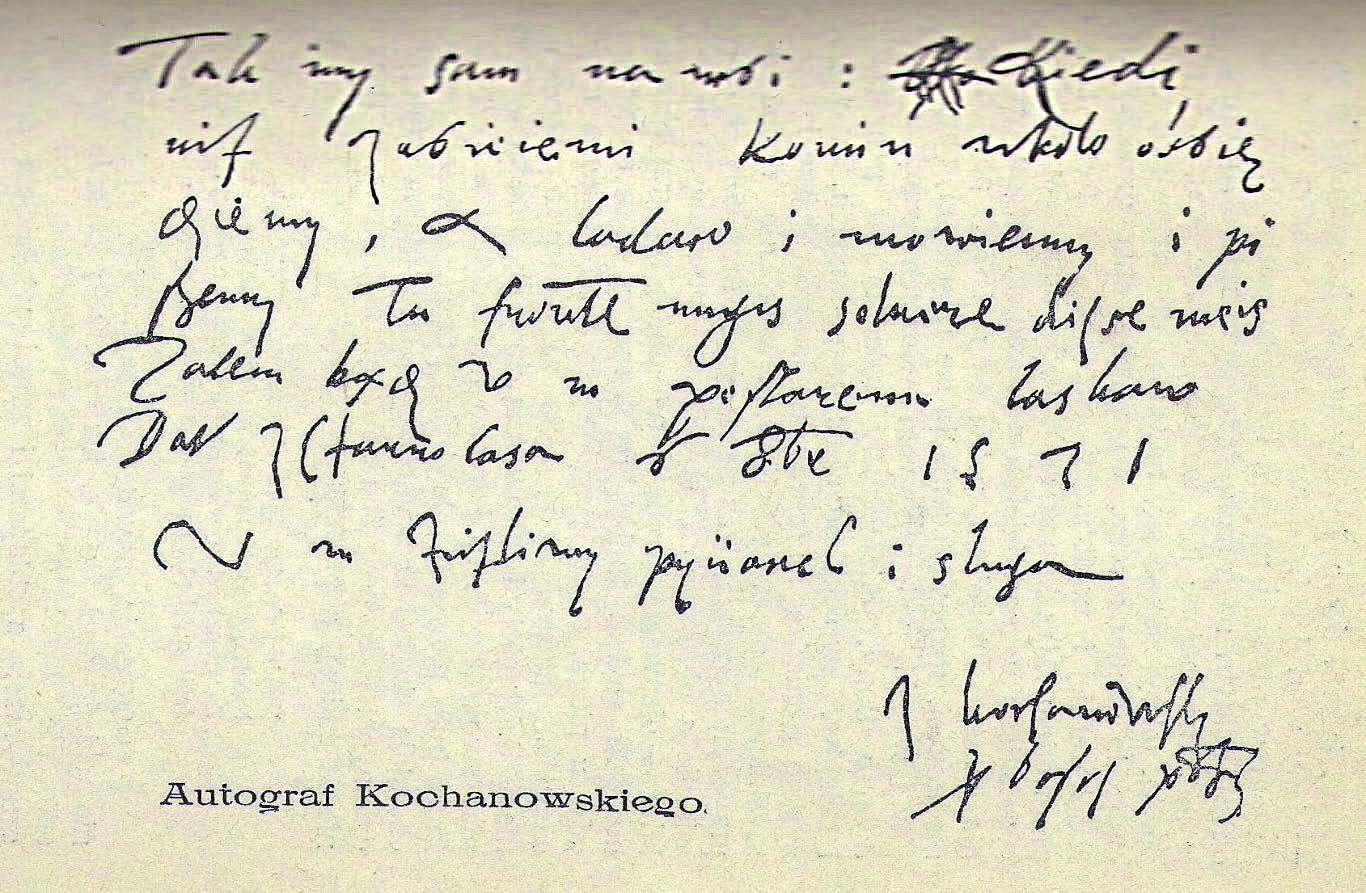

The poem Dryas ZamchanaPolish is the only known work by Jan Kochanowski in his own hand. As of May 2024, it is displayed at a permanent exhibition in the Palace of the Commonwealth in Warsaw.

5.7. Translations and Latin Works

Kochanowski also undertook significant translations of ancient classical Greek and Roman works into Polish, including the Phenomena of Aratus and fragments of Homer's Iliad, as well as fragments of Euripides' tragedy Alcestis.

His notable Latin compositions include Lyricorum libellusLatin (Little Book of Lyrics, 1580), Elegiarum libri quatuorLatin (Four Books of Elegies, 1584), and numerous occasional poems. These Latin poems were later translated into Polish by Kazimierz Brodziński in 1829 and by Władysław Syrokomla in 1851.

6. Philosophy and Thought

Jan Kochanowski's intellectual outlook was deeply shaped by his religious convictions, his commitment to religious tolerance, and the profound influence of humanism and various philosophical schools, which he skillfully integrated into his worldview.

6.1. Religious and Philosophical Stance

Kochanowski was a deeply religious man, and many of his works are inspired by his faith. However, he deliberately avoided taking sides in the intense strife between the Catholic Church and the Protestant denominations of his era. He maintained friendly relations with figures from both Christian currents, and his poetry was widely accepted by both Catholics and Protestants, a testament to his balanced and inclusive approach.

His philosophy is characterized by an eclectic blend of different schools of thought. He integrated elements of Stoicism, emphasizing virtue, reason, and emotional resilience; Epicureanism, which sought pleasure through tranquility and freedom from fear; and Renaissance Neoplatonism, which pursued ideal forms and spiritual beauty. Crucially, Kochanowski harmonized these ancient philosophical traditions with a deep, personal Christian faith, creating a unique synthesis that reflected a profound reverence for God. This philosophical synthesis allowed him to explore universal human experiences, such as joy, sorrow, and the search for meaning, through a lens that combined classical wisdom with Christian spirituality.

7. Influence and Legacy

Jan Kochanowski's influence on Polish language and literature is foundational, establishing him as a towering figure whose contributions continue to shape national cultural identity and artistic expression. His work also garnered significant recognition within broader European literary circles.

7.1. Influence on Polish Language and Literature

Kochanowski is widely regarded as the greatest Polish poet before Adam Mickiewicz and the foremost Renaissance poet not only in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth but across all Slavic nations. His preeminence remained unchallenged until the emergence of the 19th-century Polish Romantics, notably Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki, and Alexander Pushkin in Russia.

Polish literary historian Tadeusz Ulewicz credits Kochanowski with both creating modern Polish poetry and introducing it to Europe. The American Slavicist Oscar E. Swan similarly states that Kochanowski was "the first Slavic author to attain excellence on a European scale." Czesław Miłosz affirmed that "until the beginning of the nineteenth century, the most eminent Slavic poet was undoubtedly Jan Kochanowski" and that he "set the pace for the whole subsequent development of Polish poetry." The British historian Norman Davies ranks Kochanowski as the second most important figure of the Polish Renaissance, after Nicolaus Copernicus. Jerzy Jarniewicz, a Polish poet and literary critic, has called Kochanowski "the founding father of Polish literature."

A major achievement of Kochanowski was his creation of Polish-language verse forms, which made him a classic for his contemporaries and for posterity. He never ceased writing in Latin, yet he greatly enriched Polish poetry by naturalizing foreign poetic forms and imbuing them with a distinct national spirit. Davies notes that Kochanowski can be seen as "the founder of Polish vernacular poetry [who] showed the Poles the beauty of their language."

American historian Larry Wolf argues that Kochanowski "contributed to the creation of a vernacular culture in the Polish language." Elwira Buszewicz, another Polish literary historian, describes him as "the 'founding father' of elegant humanist Polish-language poetry." David Welsh, an American Slavicist and translator, considers Kochanowski's greatest achievement to be his "transformation of the Polish language as a medium for poetry." Ulewicz highlights Kochanowski's Songs as particularly influential in this regard, while Davies famously stated that "Kochanowski's Psalter did for Polish what Luther's Bible did for German." Kochanowski's works also significantly influenced the development of Lithuanian literature.

Scholars of medieval Polish emphasize that Kochanowski's language, in terms of technical skill, modernity, and conscious use of rhetoric, surpassed that of other 16th-century writers. Compared to the language of Mikołaj Rej, an earlier poet, Kochanowski's style was more modern. Many of his poems, epigrams, and elegies remain easily readable today due to their lack of archaic grammar (for instance, his use of the then-new ending '-ach' for masculine and neuter singular nouns in the prepositional case), restrained use of the dual form, and limited archaic vocabulary. Kochanowski skillfully varied his style according to the genre and theme, employing a high style for poems and elegies, while aiming for a "simple style" (incorporating elements of contemporary colloquial speech) in his epigrams. His language and style profoundly influenced the development of written Polish, serving as a model for subsequent writers until the late 18th century. Even in the late 18th century, Ignacy Krasicki proudly mentioned Kochanowski's works occupying his study in his poem "Mr. Podstoli." Adam Naruszewicz, an 18th-century poet and historian, adopted several motifs, themes, and even vocabulary from Kochanowski. During the Saxon Electorate (1697-1763), when the Polish language was somewhat neglected, Kochanowski's language was re-examined and valued for its beauty and correctness during the Enlightenment.

7.2. European Evaluation and Artistic Inspiration

Kochanowski's first published collection of poems was his David's Psalter (printed 1579). A number of his works were published posthumously, beginning with a series of volumes in Kraków from 1584 to 1590, concluding with Fragmenta albo pozostałe pismaPolish (Fragments, or Remaining Writings). This series included works from his Padua period and his Fraszki (Epigrams). A jubilee volume was published in Warsaw in 1884.

In 1875, many of Kochanowski's poems were translated into German by H. Nitschmann. In 1894, Encyclopædia Britannica referred to Kochanowski as "the prince of Polish poets." However, for a long time, he remained little known outside Slavic-language countries. The first English-language collection of his poems, translated by George R. Noyes et al., was released in 1928, and the first English-language monograph devoted to him, by David Welsh, appeared in 1974. As late as the early 1980s, Kochanowski's writings were often overlooked or given brief mention in English-language reference works. More recently, however, further English translations have appeared, including The Laments, translated by Stanisław Barańczak and Seamus Heaney (1995), and The Envoys, translated by Bill Johnston (2007).

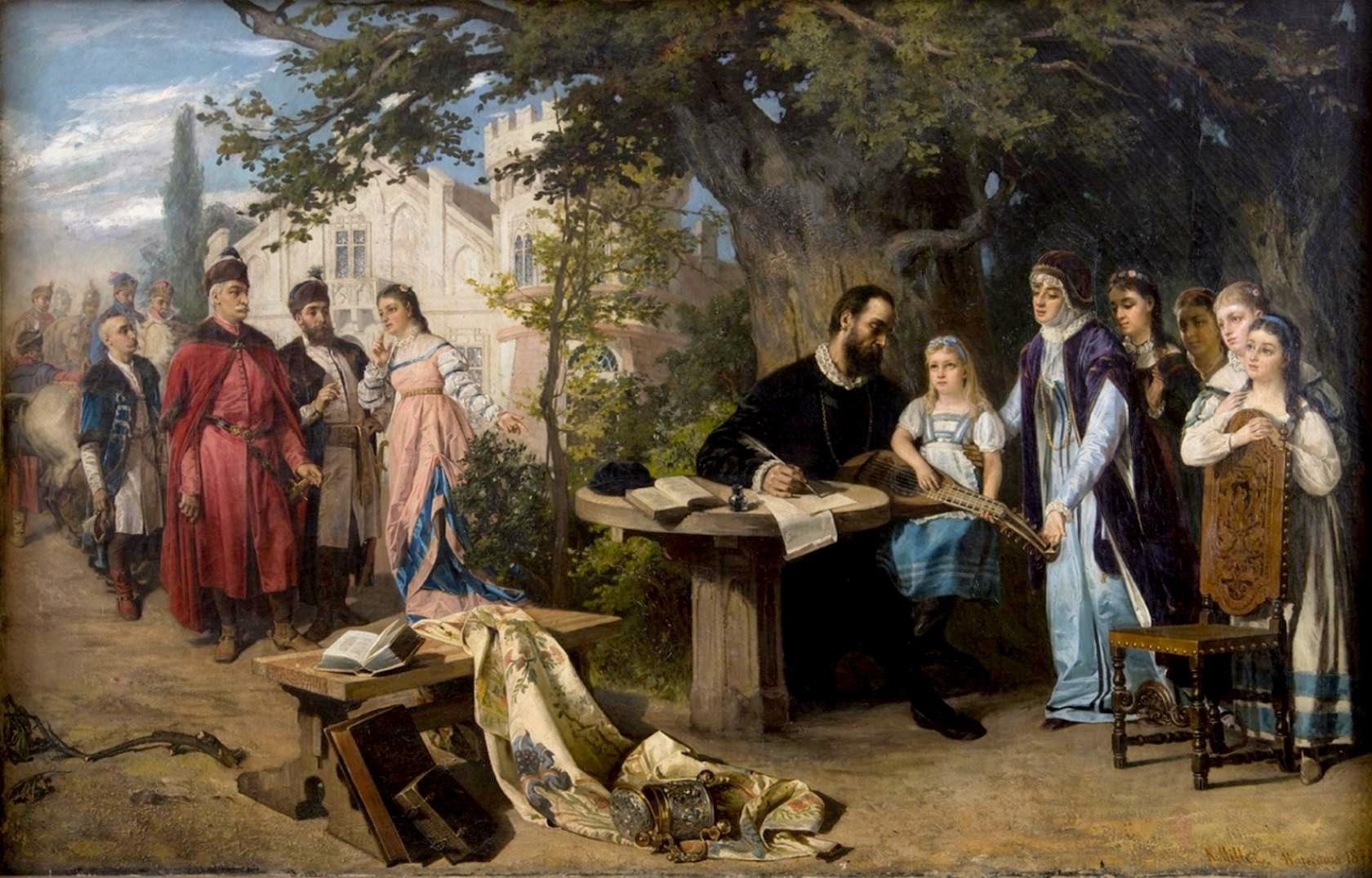

Kochanowski's complete works have served as a rich source of inspiration for modern Polish literary, musical, and visual arts. Fragments of his poetry were used by Jan Ursyn Niemcewicz in the libretto for the opera Jan Kochanowski, which was staged in Warsaw in 1817. In the 19th century, musical arrangements of his Lamentations and Psalter gained significant popularity. Stanisław Moniuszko composed songs for bass with piano accompaniment based on texts from Lamentations III, V, VI, and X. In 1862, the celebrated Polish history painter Jan Matejko depicted him in his painting Jan Kochanowski nad zwłokami UrszulkiPolish (Jan Kochanowski and his Deceased Daughter Ursula).

8. Death and Commemoration

Jan Kochanowski's death marked the end of an era for Polish literature, but his legacy has been meticulously preserved and celebrated through various commemorative efforts.

8.1. Death and Burial

Jan Kochanowski died suddenly in Lublin on 22 August 1584, at the age of 54, likely from a heart attack. He was in Lublin to present a complaint to the King regarding the murder of his brother-in-law, Jakub Podlodowski. According to historical accounts, he felt unwell on 20 September, possibly during or immediately after his audience, and passed away two days later.

He was buried in the crypt of the Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross (Kościół pw. Podwyższenia Krzyża ŚwiętegoPolish) in Zwoleń. In the early 17th century, Kochanowski's family erected a tombstone with his bust. Historical records indicate that at least two tombstones were created for Kochanowski, one in Zwoleń and another in Policzno, though neither survives today.

In 1791, on 29 April, the historian Tadeusz Czacki controversially removed Kochanowski's reputed skull from his tomb. Czacki kept the skull at his estate in Porycko (now Pavlivka, Ukraine) for several years. On 4 November 1796, he gifted it to Princess Izabela Czartoryska, who added it to the collection of the museum she was establishing in Puławy. After the November Uprising, the skull was transported to Paris and stored at the Hôtel Lambert on Île Saint-Louis. It has been housed in the Czartoryski Museum in Kraków since 1874. However, anthropological studies conducted in 2010 revealed that the skull is almost certainly that of a woman, possibly Kochanowski's wife, and its facial features do not match the bust in Zwoleń.

In 1830, the parish priest of Zwoleń removed all of the Kochanowski family's coffins from the crypt and moved them to a communal family burial ground near the church building. In 1983, the remains were returned to the crypt, specifically to a restored marble sarcophagus in the church's basement. On 21 April 1984, a commemorative reburial ceremony was held for the poet.

8.2. Legacy and Commemorative Activities

Kochanowski's sudden death prompted the publication of numerous literary works in his praise, including those by Andrzej Trzecieski (known for his Polish Bible translation), a cycle of 13 elegies by Sebastian Fabian Klonowic, and poems by Stanisław Niegoszewski, among many others. In 1584, the chronicler Joachim Bielski wrote, "Jan Kochanowski of the Korwin coat of arms has died. There is no such Polish poet in Poland anymore, and none can be expected to return."

Beyond his initial posthumous publications, which included works from his Padua period and his Fraszki, a jubilee volume was published in Warsaw in 1884. While his works were translated into German in 1875, Kochanowski remained relatively unknown outside Slavic-language countries for a long time. The first English-language collection of his poems appeared in 1928, and the first English monograph dedicated to him was published in 1974. However, more recent English translations, such as The Laments (1995) and The Envoys (2007), have increased his international recognition.

Kochanowski's oeuvre has continued to inspire modern Polish literary, musical, and visual art. In the 19th century, musical arrangements of his Lamentations and Psalter gained popularity, with Stanisław Moniuszko composing songs based on texts from the Lamentations. In 1862, the renowned Polish history painter Jan Matejko depicted him in his painting Jan Kochanowski and his Deceased Daughter Ursula. In 1961, a museum dedicated to Kochanowski, the Jan Kochanowski Museum in Czarnolas (Muzeum Jana Kochanowskiego w CzarnolesiePolish), was opened on his former estate, preserving his legacy and providing a place for scholarly and public interest in his life and work.