1. Overview

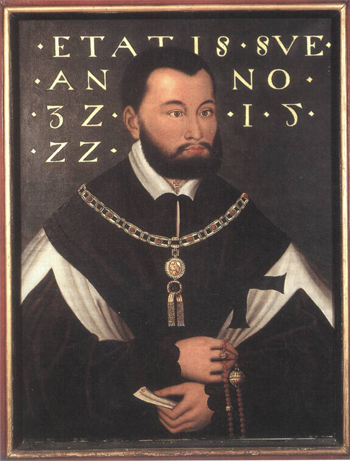

Albert of Prussia (Albrecht von PreussenAlbert of PrussiaGerman; May 17, 1490 - March 20, 1568) was a German prince who served as the 37th Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights from 1510 to 1525. After converting to Lutheranism, he became the first ruler of the Duchy of Prussia, a secularized state that emerged from the former Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights. Albert was the first European ruler to officially establish Lutheranism, and thus Protestantism, as the state religion of his lands. He was instrumental in the political spread of Protestantism in its early stages, governing the Prussian territories for nearly six decades.

A member of the Brandenburg-Ansbach branch of the House of Hohenzollern, Albert was a great-grandson of Jogaila, who had famously defeated the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald. His election as Grand Master was partly a diplomatic effort to improve relations with the Polish-Lithuanian union. Demonstrating skill in political administration, he managed to reverse the decline of the Teutonic Order. However, influenced by the teachings of Martin Luther, Albert rebelled against the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire by transforming the monastic Teutonic state into a hereditary Protestant duchy. This arrangement was formally recognized by the Treaty of Kraków in 1525, whereby he paid homage to his maternal uncle, Sigismund I, King of Poland, becoming his vassal.

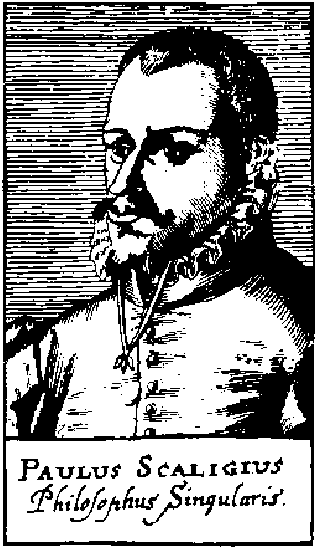

Albert's rule in Prussia was generally prosperous, marked by significant reforms in administration, education, and religion. He founded the University of Königsberg in 1544 and promoted culture and arts. However, his later years were marred by peasant unrest, increased taxation, and court intrigues involving figures like Johann Funck and Paul Skalić, leading to political and religious disputes. He died in 1568, succeeded by his son, Albert Frederick.

2. Early life and background

Albert's early life was shaped by his aristocratic lineage and an education that initially prepared him for a career within the Church, but his interests extended beyond religious dogma to encompass scientific and mathematical pursuits.

2.1. Birth and family

Albert was born in Ansbach in Franconia, a region within modern-day Bavaria, on May 17, 1490. He was the third son of Frederick I, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, and his mother was Sophia Jagiellon, a daughter of Casimir IV Jagiellon, who was Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland. His maternal grandmother was Elisabeth of Austria. Through his mother, Albert was a nephew of King Sigismund I of Poland. His great-grandfather was Jogaila, the last pagan ruler in Europe, known for defeating the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410. Albert's siblings included Casimir and George, Margraves of Kulmbach and Ansbach, respectively.

2.2. Ancestry

Albert belonged to the Brandenburg-Ansbach branch of the House of Hohenzollern, a prominent German dynasty. His paternal grandfather was Albrecht III Achilles, who was Elector of Brandenburg and Margrave of Ansbach. Albrecht III's first son, John Cicero, was a direct ancestor of later Prussian monarchs such as Frederick the Great and Wilhelm I. Albert's paternal great-grandfather, Frederick I, Burgrave of Nuremberg, received the Electorate of Brandenburg from Emperor Sigismund in 1415. The Hohenzollerns gained control over various territories through strategic inheritances and acquisitions, which shaped the dynastic landscape Albert inherited.

Albert's lineage also included complex intermarriages. His second wife, Anna Maria of Brunswick-Lüneburg, was a daughter of Eric I of Brunswick-Lüneburg. Eric I was a grandson of Cecilia, who was Albert's paternal great-great-aunt (daughter of Elector Frederick I). Eric I's wife, Elisabeth of Brandenburg, was a granddaughter of Albert's paternal great-uncle, John Cicero, and therefore Albert's first cousin once removed. This meant Albert's second wife was his second cousin once removed, and his mother-in-law was his first cousin once removed.

2.3. Education and early career

Albert's upbringing was initially geared towards a career in the Roman Catholic Church. He spent time at the court of Hermann IV of Hesse, the Elector of Cologne, who appointed him as a canon of the Cologne Cathedral. Despite his religious education, Albert developed a strong interest in mathematics and science. He was known to question Church teachings based on scientific theories, an uncommon stance for a cleric of his time. This interest was, surprisingly, sometimes supported by other Catholic clerics and institutions.

In 1508, seeking a more active life, Albert accompanied Emperor Maximilian I on a journey to Italy. After his return, he also spent some time in the Kingdom of Hungary. These early travels and experiences provided him with a broader understanding of European politics and culture, which would prove valuable in his later leadership roles.

3. Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights

Albert's tenure as the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights was a period of significant challenge, marked by ongoing conflicts with Poland and the profound influence of the nascent Reformation.

3.1. Election and tenure

In December 1510, Duke Frederick of Saxony, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, died. Albert was chosen as his successor in early 1511, becoming the 37th Grand Master. His selection was largely influenced by the hope that his familial connection to his maternal uncle, Sigismund I the Old, who was Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, would facilitate a peaceful resolution to the protracted disputes over eastern Prussia. This territory had been held by the Order under Polish suzerainty since the Second Peace of Thorn (1466). However, Albert's appointment came with the condition that he would not provide military assistance to Poland. He served as Grand Master for 16 years, from 1510 to 1525.

3.2. Relations with Poland and conflicts

Upon assuming his role, Albert was acutely aware of his duties to both the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy. Consequently, he refused to submit to the Polish Crown, escalating the existing tensions. As war over the Order's existence appeared inevitable, Albert diligently sought allies and engaged in lengthy negotiations with Emperor Maximilian I. The strained relations, exacerbated by the devastations caused by members of the Order in Poland, culminated in the Polish-Teutonic War, which commenced in December 1519 and severely ravaged Prussia. Facing dire circumstances, Albert secured a four-year truce in early 1521.

The dispute was then referred to Emperor Charles V and other German princes, but no lasting settlement was reached. Albert continued his efforts to secure aid in anticipation of a renewed conflict.

3.3. Influence of the Reformation

During his diplomatic efforts, Albert attended the Diet of Nuremberg in 1522. There, he made the acquaintance of the Reformer Andreas Osiander, whose influence proved pivotal in converting Albert to Protestantism. Osiander repeatedly encouraged Albert to actively participate in the Lutheran movement.

Later in 1522, Albert journeyed to Wittenberg to meet Martin Luther. Luther advised him to abandon the monastic rules of the Teutonic Order, to marry, and to convert Prussia into a hereditary duchy under his personal rule. This proposal, highly appealing to Albert, had already been discussed with some of his relatives. However, caution was necessary. Albert assured Pope Adrian VI that he intended to reform the Order and punish knights who had embraced Lutheran doctrines. Meanwhile, Luther actively promoted his teachings among the Prussians to facilitate the impending change, while Albert's brother, Margrave George of Brandenburg-Ansbach, presented the secularization plan to their uncle, Sigismund I of Poland.

4. Conversion to Protestantism and founding of the Duchy of Prussia

Albert's decision to convert to Lutheranism marked a revolutionary turning point, leading to the secularization of the Teutonic State and the establishment of the Duchy of Prussia under Polish suzerainty.

4.1. Embracing Lutheranism

On February 10, 1525, Albert officially converted to Protestantism, thereby relinquishing his status as a knight and priest and enabling him to marry and have legitimate heirs. His conversion was profoundly influenced by his discussions with Martin Luther, who encouraged him to abandon Catholic doctrine and establish a new secular state. This personal religious shift had monumental implications for his political identity and the future of Prussia.

4.2. Secularization of the Teutonic State

Albert transformed the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights into the secular Duchy of Prussia. This radical shift meant abandoning centuries of ecclesiastical rule and establishing a hereditary dukedom. The new capital of this duchy was Königsberg. Upon his return from Poland to Königsberg, Albert publicly declared his Protestant conversion. This move shocked the remaining Teutonic Knights, who openly opposed his decision and demanded he revert to Catholicism. Albert, however, had secured significant support from the citizens of Königsberg and responded by compelling the members of the Teutonic Order's Prussian branch to convert to Lutheranism. Although a few, like Erich von Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, the commander of Memmert, stubbornly adhered to Roman Catholicism, many high-ranking commanders, including the Grand Commander, Grand Hospitaler, Treasurer, and Draper of the Order, who had pledged loyalty to Albert after his resignation as Grand Master, abandoned him to maintain their Catholic faith. By the time of Albert's death, only 55 knights remained in the Teutonic Order. Those who stayed expressed their discontent with Albert's conversion and the perceived failure of Prussia to his successor, Walter von Cronberg. Albert also declared religious freedom and secular governance in his newly founded duchy, breaking from the European norm of rulers upholding state religions. This pioneering move influenced others, such as Gotthard Kettler, the head of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, who also secularized his territory into the Duchy of Courland in 1526.

4.3. Homage to Poland

After some deliberation, King Sigismund I of Poland assented to Albert's proposal, with the crucial provision that Prussia would be treated as a fief of the Polish Crown. This arrangement was formalized by the Treaty of Kraków on April 10, 1525. Following the treaty, Albert pledged a personal oath of allegiance to Sigismund I and was formally invested with the duchy for himself and his heirs. The Estates of the realm then convened at Königsberg and swore loyalty to the new duke, who immediately began promoting the doctrines of Luther.

This transition, however, was not without opposition. Albert was summoned before the Imperial Court of Justice of the Holy Roman Empire but refused to appear and was consequently proscribed. The Teutonic Order elected a new Grand Master, Walter von Cronberg, who received Prussia as a fief at the imperial Diet of Augsburg. However, as the German princes were preoccupied with the turmoil of the Reformation, the German Peasants' War, and the wars against the Ottoman Turks, they did not enforce the ban on Albert. The agitation against him gradually subsided. Emperor Charles V and Pope Clement VII sarcastically referred to this agreement as "the cow trade of Kraków," highlighting their disapproval of a Catholic monarch supporting a Protestant vassal.

5. Rule as Duke of Prussia

Albert's reign as the first Duke of Prussia was marked by significant administrative, educational, religious, and political initiatives, establishing a foundation for the nascent duchy.

5.1. Administration and governance

The early years of Albert's rule in Prussia were notably prosperous. Despite some initial challenges with the peasantry, the confiscation of vast lands and treasures from the Catholic Church allowed him to conciliate the nobility and cover the expenses of the newly established Prussian court. However, in his later years, as these church lands became depleted, Albert was compelled to raise taxes, leading to an increased burden on the populace and contributing to peasant unrest. From the outset of his reign, he weakened the power of the nobility by emancipating serfs. He implemented policies to improve their conditions and integrate them into the new societal structure.

5.2. Promotion of education and scholarship

Albert made significant contributions to the advancement of learning. He mandated the establishment of schools in every town, providing educational opportunities for freed serfs and their children. In 1544, despite some opposition, he founded the University of Königsberg, famously known as the Albertina. This institution was established in part as a rival to the Catholic-leaning Kraków Academy and became the second Lutheran university in the German states, after the University of Marburg. Albert appointed his friend Andreas Osiander to a professorship there in 1549. He personally covered the printing costs for German textbooks and Protestant catechisms. He also supported the translation and publication of astronomical works in 1549.

Albert was a prominent patron of arts and sciences. He supported the printing of the astronomical "Prutenic Tables", compiled by Erasmus Reinhold, and the creation of the first maps of Prussia by Caspar Hennenberger. Notably, Albert was one of the first rulers in Poland and Europe to officially endorse Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric theory. Copernicus, who served as a diplomat and physician to the Polish Crown, also treated Albert's close associates. Albert encouraged Lutheran astronomers within Prussia to use the Copernican system for their astronomical calculations, which influenced the calendar reforms of Pope Gregory XIII. He also founded a public library in Königsberg.

5.4. Political activities and diplomacy

Albert remained actively engaged in broader imperial politics. In 1526, he joined the League of Torgau, aligning himself with other Protestant princes. He was among the rulers who conspired to overthrow Emperor Charles V following the issuance of the Augsburg Interim in May 1548. However, due to various reasons, including financial constraints and personal inclination, he did not play a prominent military role in the operations of this period. He maintained extensive correspondence with many leading figures of his time, and many of his letters have been preserved.

6. Personal life

Albert's personal life included two marriages that provided dynastic continuity for the Duchy of Prussia.

6.1. Marriages and issue

Albert married his first wife, Dorothea (August 1, 1504 - April 11, 1547), in 1526. She was the daughter of King Frederick I of Denmark. This marriage was also a strategic alliance, as Denmark had a significant Lutheran population. They had six children:

- Anna Sophia (June 11, 1527 - February 6, 1591), who married John Albert I, Duke of Mecklenburg-Güstrow.

- Katharina (born and died February 24, 1528) who died at birth.

- Frederick Albert (December 5, 1529 - January 1, 1530) who died young.

- Lucia Dorothea (April 8, 1531 - February 1, 1532) who died in infancy.

- Lucia (February 3, 1537 - May 1, 1539) who died young.

- Albert (born and died March 1, 1539) who died at birth.

After Dorothea's death, Albert married his second wife, Anna Maria (1532 - March 20, 1568), in 1550. She was the daughter of Eric I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. They had two children:

- Elisabeth (May 20, 1551 - February 19, 1596), who died unmarried and without issue.

- Albert Frederick (April 29, 1553 - August 18, 1618), who succeeded him as Duke of Prussia.

7. Later years and controversies

The closing years of Albert's reign were marred by increasing internal challenges, including theological disputes, court intrigues, and social unrest, which significantly diminished his effective power.

7.1. Religious and political disputes

The appointment of Andreas Osiander to a professorship at Königsberg University in 1549 marked the beginning of significant troubles. Osiander's theological deviations from Luther's doctrine of justification by faith led him into a fierce quarrel with Philip Melanchthon, whose adherents were present in Königsberg. These theological disputes rapidly escalated, causing considerable uproar in the city. Albert strongly supported Osiander, expanding the scope of the controversy. As there were no longer church lands available to placate the nobility, and the burden of taxation grew heavier, Albert's rule became increasingly unpopular.

Following Osiander's death in 1552, Albert favored Johann Funck, a preacher who, alongside an adventurer named Paul Skalić, exerted immense influence over the Duke. Funck and Skalić accumulated substantial wealth at public expense. Funck also pressured Albert to condemn Osiander's teachings. The political and religious turmoil caused by these intrigues was compounded by the potential for Albert's impending death and the necessity of appointing a regent, as his only son, Albert Frederick, was still a minor. The situation reached a climax in 1566 when the Estates appealed to King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland, Albert's cousin, who dispatched a commission to Königsberg. Skalić managed to escape, but Funck was executed. The issue of the regency was resolved, and a specific form of Lutheranism was adopted and declared binding for all teachers and preachers.

7.2. Peasant unrest and internal strife

Albert faced considerable peasant unrest, particularly the "Samland Rebellion" in 1525. The revolt was fueled by peasant dissatisfaction with excessive taxation and forced labor imposed by the nobility, as well as general grievances against Albert's recent conversion to Protestantism and the secularization of the state. Led by a farmer from Kaimen and an innkeeper from Schacken, the rebels garnered broad support from Königsberg citizens. The peasant forces demanded an end to compulsory noble taxation, the abolition of all forms of noble-imposed taxes, a reduction of taxes to two marks, and the free distribution of one *Hufe* (a unit of land) to peasants. The rebels asserted that their resistance was against the nobility's harshness, not against Albert himself.

Albert convened a meeting with the peasant leaders to address their demands. During the negotiations, the two peasant leaders were executed for treason. However, Albert did concede to some of the peasants' conditions, which led to the gradual dissolution of the rebel forces. These incidents contributed to Prussia's reputation as a region characterized by Protestantism and factionalism.

8. Death

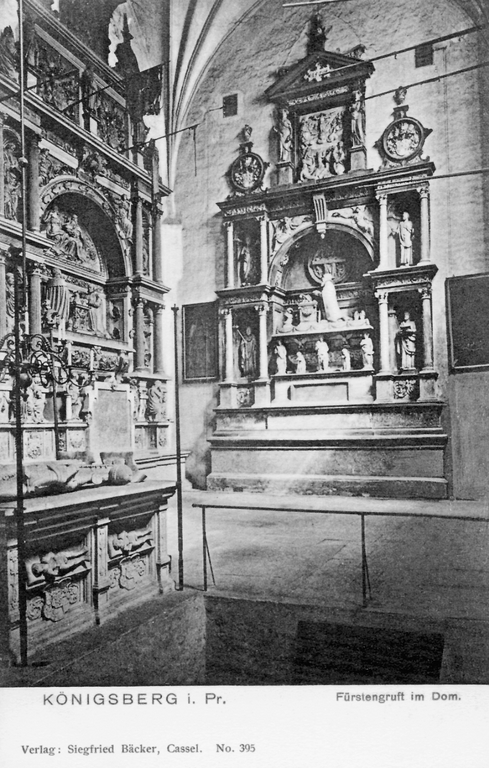

Albert lived for two more years after being virtually deprived of power due to the controversies of his later reign. He died at Tapiau on March 20, 1568. His death was attributed to the plague, and tragically, his second wife, Anna Maria, also succumbed to the same disease within 16 hours on the very same day. Albert's body was interred in Königsberg Cathedral, where his tomb was designed by the renowned artist Cornelis Floris de Vriendt.

9. Legacy and evaluation

Albert's legacy is multifaceted, reflecting his pivotal role in transforming the political and religious landscape of Prussia and his enduring impact on education and culture.

9.1. Positive contributions

Albert's most significant achievement was the establishment of the Duchy of Prussia in 1525, converting the long-standing monastic state of the Teutonic Knights into a secular, hereditary dukedom. This act laid the foundation for the future Prussian state. He was the first German noble to unequivocally support the ideas of Martin Luther and played a crucial role in the early political dissemination of Protestantism by making Lutheranism the official state religion of his territory.

His commitment to education and scholarship was profound. In 1544, he founded the University of Königsberg, known as the Albertina, which became the second Lutheran university in the German states, following the University of Marburg. He also established schools in every town and actively promoted culture and arts, patronizing scholars like Erasmus Reinhold and Caspar Hennenberger, and supporting Copernican astronomy. His initiatives contributed significantly to the intellectual and cultural development of Prussia.

9.2. Criticism and controversies

Despite his progressive reforms, Albert faced various criticisms and controversies during his reign. His handling of financial matters, particularly the reliance on confiscating church lands which eventually led to increased taxation, caused widespread discontent among the peasantry. His support for Andreas Osiander's theological views sparked major religious disputes within his duchy, causing instability and unrest. Furthermore, the undue influence of court favorites like Johann Funck and Paul Skalić led to accusations of corruption and further political turmoil, ultimately undermining Albert's authority in his final years.

9.3. Impact on Prussia and Protestantism

Albert's actions irrevocably shaped the political and religious landscape of Prussia. By secularizing the Teutonic Order's state and adopting Lutheranism, he created a unique entity in Europe-a Protestant duchy under the suzerainty of a Catholic Polish king. This pioneering move helped to solidify Protestantism in the region and contributed to its broader dissemination across Europe. His decision to declare the Duchy of Prussia a secular state, permitting religious freedom for various beliefs, was a significant departure from prevailing European norms. This influenced other rulers, such as Gotthard Kettler, who similarly secularized the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order to form the Duchy of Courland.

9.4. Commemoration and memorials

Albert of Prussia has been commemorated in various forms, reflecting his enduring historical significance. A relief of Albert, created by Andreas Hess in 1551 based on Christoph Römer's plans, is located over the Renaissance-era portal of Königsberg Castle's southern wing. Another relief by an unknown artist, depicting the duke with a sword over his shoulder, became the popular "Albertus," a symbol of Königsberg University. The original "Albertus" was moved to the Königsberg Public Library for preservation, with a duplicate created by sculptor Paul Kimritz for the wall. A version by Lothar Sauer was also placed at the entrance of the Königsberg State and Royal Library.

In 1880, Friedrich Reusch created a sandstone bust of Albert for the Regierungsgebäude, the administrative building for Regierungsbezirk Königsberg. Reusch also unveiled a famous statue of Albert at Königsberg Castle on May 19, 1891, bearing the inscription: "Albert of Brandenburg, Last Grand Master, First Duke in Prussia." Albert Wolff designed an equestrian statue of Albert for the new campus of the Albertina. The King's Gate in Kaliningrad also features a statue of Albert. In Königsberg's northern quarter of Maraunenhof, Albert was frequently honored: its main street was named Herzog-Albrecht-Allee in 1906, and its town square, König-Ottokar-Platz, was renamed Herzog-Albrecht-Platz in 1934 to match the nearby Herzog-Albrecht-Gedächtniskirche (Albert Memorial Church).