1. Overview

Publius Vergilius Maro, commonly known as Virgil or Vergil, was an influential ancient Roman poet who lived from 70 BC to 19 BC, during the late Roman Republic and early Augustan period. He is widely celebrated for his three monumental works in Latin literature: the pastoral collection Eclogues (also known as Bucolics), the didactic poem Georgics, and most notably, the epic Aeneid. The Aeneid, commissioned by Emperor Augustus, stands as the national epic of Rome, chronicling the mythical origins of the city through the journey of the Trojan hero Aeneas.

Virgil's poetic contributions not only revolutionized Latin verse but also exerted an unparalleled and enduring influence on subsequent Western literature, earning him the title of the "Roman Homer" and, later, the "poet of all Europe." His meticulous craftsmanship, profound philosophical insights, and evocative descriptions have ensured his status as a classical author whose works continue to be studied and admired for their universal value and artistic excellence, even when viewed through critical lenses regarding their historical or political context.

2. Life

Virgil's life, from his humble beginnings to his celebrated status as Rome's foremost poet, unfolded during a period of intense political upheaval and the subsequent establishment of the Roman Empire. While biographical accounts from antiquity exist, their reliability can be problematic due to reliance on allegorical interpretations of his poetry.

2.1. Biographical Sources

Primary biographical information about Virgil stems mainly from ancient texts known as *vitae* ('lives') of the poet, which often served as prefaces to commentaries on his works. Key figures providing these accounts include Probus, Donatus, and Servius. Donatus's biography is widely believed to be a close reproduction of a lost work by Suetonius on the lives of famous authors, a source Donatus explicitly credited in his commentary on Terence. Similarly, Servius's shorter account appears to be an abridgement of Suetonius's work, with only minor deviations.

Varius Rufus, a close friend of Virgil and one of his literary executors, is said to have written a memoir of the poet, which Suetonius likely drew upon, alongside other contemporary sources. A biography in verse by the grammarian Phocas, active in the 4th to 5th centuries AD, offers some differing details from Donatus and Servius. The life attributed to Probus may have independently used the same sources as Suetonius, though some scholars attribute it to an anonymous 5th or 6th-century author who synthesized information from Donatus, Servius, and Phocas. The Servian life was the principal source for medieval readers, while Donatus's account had more limited circulation, and the works of Phocas and Probus remained largely obscure.

Despite the wealth of factual information in these commentaries, modern scholarship notes that some evidence is based on allegorizing and inferences drawn from Virgil's poetry rather than direct historical records. Consequently, certain details about Virgil's life are considered to be somewhat problematic or subject to debate.

2.2. Birth and Early Life

Publius Vergilius Maro was born on October 15, 70 BC, during the consulship of Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus, in the village of Andes, near Mantua in Cisalpine Gaul. This region, located in northern Italy, was later incorporated into Roman Italy during Virgil's lifetime.

According to ancient *vitae*, his family background was modest, though accounts vary. The Donatian life suggests his father was either a potter or an employee of an apparitor named Magius, whose daughter he married. Phocas and Probus record his mother's name as Magia Polla. The family of his mother, *Magius*, and the misinterpretation of its genitive form (*Magi*) as "magician" in Servius's life, likely contributed to the medieval legends portraying Virgil as a magician. Despite claims of modest means, the details of his education and ceremonial assumption of the *toga virilis* suggest his father was a wealthy equestrian landowner.

The precise location of Andes has been a subject of historical debate. A tradition, accepted by Dante, identifies Andes with modern Pietole, about 2 mile or 3 mile southeast of Mantua. However, the ancient biography by Probus states that Andes was 30 mile from Mantua. Inscriptions found in Northern Italy, particularly near Calvisano, which is exactly 30 mile from Mantua, suggest it might be the true site. A tomb from Virgil's mother's family, the *gens Magia*, is located at Casalpoglio, only 7.5 mile (12 km) from Calvisano. Some modern studies claim that ancient Andes should be sought in the Casalpoglio area of Castel Goffredo.

The spelling of his name also underwent changes. By the 4th or 5th century AD, the original spelling Vergilius evolved into Virgilius, which then spread throughout modern European languages. Although the classical scholar Angelo Poliziano demonstrated Vergilius to be the original spelling in the 15th century, the spelling Virgil persisted. Today, both anglicizations, Vergil and Virgil, are considered acceptable. Some speculate that the Virgilius spelling arose from a pun on the Latin word uirga ('wand'), connecting him to medieval magic legends, or virgo ('virgin'), alluding to the "Messianic" Fourth Eclogue and its Christian interpretations.

2.3. Education and Youth

Virgil spent his early boyhood in Cremona, where he received his initial education, until his 15th year (55 BC), when he received the *toga virilis* (the toga of manhood). According to tradition, this coincided with the death of Lucretius. From Cremona, he moved to Milan and then to Rome, where he studied rhetoric, medicine, and astronomy. He initially considered a career in rhetoric and law, even appearing once in court, but his poor and hesitant speaking ability hindered his progress.

His health was generally poor throughout his life, suffering from headaches, stomach pains, and occasionally spitting blood, leading him to live somewhat like an invalid. Schoolmates perceived him as extremely shy and reserved, giving him the nickname "Parthenias" ("virgin") due to his social aloofness.

He later moved to Naples, where he deeply engaged with philosophy, particularly the Epicurean school led by Siro the Epicurean. This philosophical pursuit marked a turning point, as he abandoned his legal aspirations to dedicate his talents to poetry. The *Catalepton*, a collection of short poems possibly genuine, suggests he began writing poetry during his time at Siro's Epicurean school in Naples.

2.4. Early Poetic Career and Patronage

The biographical tradition suggests that Virgil began composing the hexameter Eclogues (or Bucolics) in 42 BC, with the collection thought to be published around 39-38 BC, although this timing remains controversial. A long-held tradition asserted that Virgil's motivation for composing the Eclogues stemmed from the confiscation of his family's land near Mantua by Octavian (later Emperor Augustus), who needed to pay off his veterans after the Battle of Philippi (42 BC). This narrative claimed Virgil used his poetry as a petition to regain his property. However, modern scholarship largely dismisses this as an unsupported inference derived from allegorical interpretations of the Eclogues. While Eclogues 1 and 9 indeed dramatize the contrasting emotions evoked by the brutality of land expropriations through pastoral idiom, they offer no definitive evidence of this specific biographical incident.

Sometime after the publication of the Eclogues, likely before 37 BC, Virgil joined the influential literary circle of Maecenas, Octavian's astute political agent. Maecenas actively sought to win over leading Roman literary figures to Octavian's side, countering pro-Antony sentiments among the elite. Within this circle, Virgil befriended many prominent literary figures of his era, including Horace, who frequently mentions Virgil in his own poetry, and Varius Rufus, who would later play a crucial role in editing the unfinished Aeneid. This patronage provided Virgil with financial security and a conducive environment for his poetic development.

2.5. Later Poetic Career and Imperial Patronage

At the insistence of Maecenas, according to tradition, Virgil dedicated the subsequent years (approximately 37-29 BC) to composing the long dactylic hexameter poem titled the Georgics. This didactic poem, whose Greek title means "On Working the Earth," was dedicated to Maecenas and aimed to revive interest in agriculture and rural life in Italy, which had suffered greatly from decades of civil war. It promoted Octavian's vision of national recovery and self-sufficiency.

Virgil embarked on his magnum opus, the Aeneid, during the last eleven years of his life (29-19 BC). This epic was commissioned by Emperor Augustus himself, who, according to the poet Propertius, desired a national epic that would glorify Rome and its new imperial dynasty. Augustus maintained a keen interest in the poem's progress, even sending letters from his military campaigns inquiring about its development. The Aeneid was intended to provide a mythical foundation for Rome's origins and a powerful narrative supporting the Augustan regime's ideals of peace, piety, and Roman destiny.

2.6. Death and Burial

In approximately 19 BC, Virgil traveled to the Roman province of Achaea in Greece with the intention of revising his unfinished Aeneid. While there, he met Emperor Augustus in Athens. Deciding to return to Italy, Virgil contracted a fever after visiting a town near Megara. Weakened by his illness, he completed his journey to Italy by ship, but died in Brundisium (in Apulia, modern-day Calabria) on September 21, 19 BC. Some late manuscripts of Servius, however, place his death in Taranto.

Before his death, Virgil expressed a strong wish for his unfinished manuscript of the Aeneid to be burned, fearing it was imperfect. However, Emperor Augustus intervened, ordering Virgil's literary executors, Lucius Varius Rufus and Plotius Tucca, to disregard this wish. Instead, Augustus commanded that the epic be published with as few editorial changes as possible, recognizing its immense cultural and political significance.

Virgil's remains were transported to Naples, where he was buried. His tomb, located near the Mergellina harbor in the Piedigrotta district, about 1.9 mile (3 km) from the center of Naples, was reportedly engraved with an epitaph he composed himself:

:Mantua me genuit; Calabri rapuere; tenet nunc Parthenope. Cecini pascua, rura, ducesLatin

:"Mantua gave me life, the Calabrians took it away, Naples holds me now; I sang of pastures, farms, and commanders."

Martial recounts that Silius Italicus later annexed the site to his estate, and Pliny the Younger noted that Silius "would visit Virgil's tomb as if it were a temple." The structure known as Virgil's tomb is found at the entrance of an ancient Roman tunnel (known as *grotta vecchia*). While already revered during his lifetime, Virgil's name became associated with miraculous powers in the Middle Ages, and for several centuries, his tomb became a destination for pilgrimages, continuing to attract visitors even today.

3. Works

Virgil's literary output, though relatively small in number of major works, profoundly shaped Latin literature and Western poetic tradition. His progression from pastoral to didactic to epic poetry demonstrates a remarkable artistic evolution and engagement with the political and social currents of his time.

3.1. Early Works (Appendix Vergiliana)

The Appendix Vergiliana is a collection of minor poems traditionally attributed to Virgil's youth. According to ancient commentators, these works were gathered by friends of the poet after his death. The collection includes approximately fourteen short poems, such as the Catalepton ("Trifles"), some of which are considered genuinely Virgilian by modern scholars. The Catalepton suggests that Virgil began writing poetry while studying Epicurean philosophy with Siro the Epicurean in Naples. Another notable piece in the *Appendix* is the short narrative poem Culex ("The Gnat"), which was attributed to Virgil as early as the 1st century AD, though its authenticity remains debated by modern scholars, who largely consider most works in the collection spurious. These early pieces often reflect stylistic influences of the neoteric poets, such as Catullus, with whom Virgil may have had some association.

3.2. Eclogues

The Eclogues (from the Greek for "selections"), also known as Bucolics, represent Virgil's first major published work. Composed in dactylic hexameter, these ten poems are largely modeled on the bucolic or pastoral poetry of the Hellenistic Greek poet Theocritus. While Theocritus rooted his pastoral scenes in specific Greek islands, Virgil elevated the pastoral setting of Arcadia into a timeless, idealized poetic landscape, influencing subsequent Western literature and visual arts profoundly.

The themes explored in the Eclogues offer a fresh perspective on traditional pastoral motifs. Eclogues 1 and 9 directly address the disruptive impact of land confiscations on the Italian countryside, reflecting the contemporary political climate following Octavian's victory at Philippi. Eclogues 2 and 3 delve into pastoral and erotic themes, depicting both homosexual and general attractions. Eclogue 4, famously known as the "Messianic Eclogue" and addressed to Asinius Pollio, uses imagery of a coming golden age associated with the birth of a child. The identity of this child has been a subject of extensive debate, with later Christian theologians interpreting it as a prophecy of Jesus's birth. Other poems like Eclogues 5 and 8 explore the myth of Daphnis through song contests, Eclogue 6 features the cosmic and mythological song of Silenus, Eclogue 7 depicts a heated poetic competition, and Eclogue 10 laments the sufferings of the elegiac poet Cornelius Gallus.

Virgil's innovative use of pastoral idiom, while rooted in Theocritus, established a distinct Latin pastoral tradition that influenced later writers such as Calpurnius Siculus and Nemesianus.

3.3. Georgics

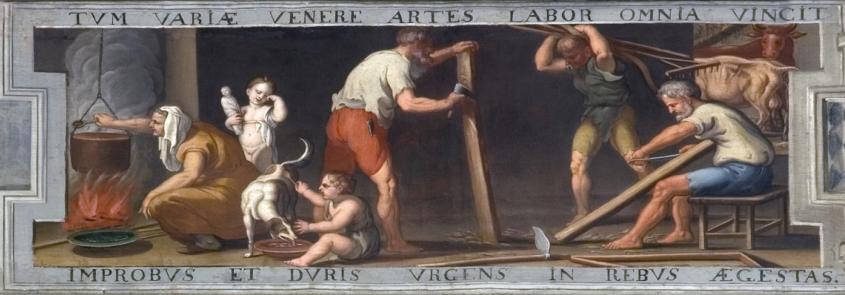

The Georgics, a didactic poem in four books composed in dactylic hexameter, was written between approximately 37 BC and 29 BC. Dedicated to Maecenas, the poem's ostensible purpose is to instruct readers on various aspects of farming. In this, Virgil follows the tradition of Greek didactic poets like Hesiod (author of Works and Days) and later Hellenistic poets.

The four books are structured thematically:

- Book 1:** Focuses on raising crops, including agricultural techniques and the challenges posed by weather and pests.

- Book 2:** Deals with the cultivation of trees, particularly grapevines and olive trees, celebrating the bounty and beauty of the Italian landscape.

- Book 3:** Discusses livestock and horses, offering advice on breeding, diseases, and their care. It includes a grim description of a plague affecting animals.

- Book 4:** Concentrates on beekeeping, detailing the social organization of bees, methods of cultivating honey, and their unique qualities. This book famously concludes with a long mythological narrative, an epyllion, recounting the discovery of beekeeping by Aristaeus and the tragic story of Orpheus's journey to the Underworld.

Notable passages include the beloved Laus Italiae (Praise of Italy) in Book 2, a vivid description of a temple in the prologue of Book 3, and the plague narrative at the end of Book 3. Ancient scholars, such as Servius, conjectured that the Aristaeus episode in Book 4 replaced an earlier, lengthy section praising Virgil's friend, the poet Gallus, who had fallen out of favor with Augustus and committed suicide in 26 BC.

The tone of the Georgics fluctuates between optimism, celebrating the dignity of labor and the pastoral ideal, and pessimism, acknowledging the harsh realities and uncertainties of rural life. This oscillation has led to ongoing critical debate about the poet's true intentions and underlying message. Despite this, the work served as a foundational model for subsequent didactic poetry in Western literature.

3.4. Aeneid

The Aeneid is universally considered Virgil's masterpiece and the national epic of ancient Rome. It is regarded as one of the most significant poems in Western literary history, with T. S. Eliot famously referring to it as "the classic of all Europe."

3.4.1. Content and Structure

The Aeneid is a 12-book epic poem composed in dactylic hexameter. Its central narrative follows the Trojan War hero Aeneas, a warrior fleeing the sack of Troy, as he embarks on a arduous journey to Italy to fulfill his destiny: to establish a new city from which Rome would eventually emerge, and from whose lineage Romulus and Remus would found the eternal city.

Virgil structured the Aeneid with clear influences from Homer's Greek epics. The first six books are modeled after the Odyssey, detailing Aeneas's travels, wanderings, and struggles across the Mediterranean. Book 1 opens with a storm stirred up by Aeneas's enemy Juno, driving his fleet to Carthage. There, Queen Dido welcomes him, and under divine influence, falls deeply in love. In Books 2 and 3, Aeneas recounts the fall of Troy and his subsequent wanderings. Book 4 sees Jupiter reminding Aeneas of his duty, prompting his departure from Carthage, which leads to Dido's tragic suicide and curse upon Aeneas, foreshadowing the Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage. Book 5 describes funeral games for Aeneas's father Anchises. The first half culminates in Book 6, where Aeneas consults the Cumaean Sibyl and descends into the Underworld, meeting the shade of Anchises, who reveals Rome's glorious destiny.

The latter six books parallel Homer's Iliad, focusing on Aeneas's battles and the establishment of his settlement in Italy. Book 7 marks Aeneas's arrival in Italy and his betrothal to Lavinia, daughter of King Latinus. This sparks conflict with Turnus, king of the Rutulians, to whom Lavinia was already promised, escalating into war. In Book 8, Aeneas allies with King Evander at the future site of Rome and receives new armor, including a shield depicting future Roman history and Augustus's victory at Actium. Books 9 to 11 narrate various battles, including the assault by Nisus and Euryalus, the death of Evander's son Pallas, and the death of the Volscian warrior princess Camilla. The epic concludes in Book 12 with the capture of Latinus's city, the death of Amata, and Aeneas's climactic duel with and merciless killing of Turnus, despite the latter's pleas for mercy. The final image is Turnus's soul fleeing to the underworld, leaving the poem with a stark, unsettling ending that contrasts with the earlier themes of Roman piety.

3.4.2. Composition and Incompleteness

The Aeneid was a commissioned work, specifically requested by Emperor Augustus, who envisioned a grand epic that would legitimize and glorify Rome's foundation and his own reign. Virgil dedicated the last eleven years of his life, from 29 BC to 19 BC, to its composition.

Despite this extended period of intense work, the poem remained unfinished at the time of Virgil's death. It is said that some lines were left metrically incomplete, and the entire text was unedited. Ancient sources claim that Virgil, on his deathbed, expressed a strong desire for the manuscript of the Aeneid to be burned, fearing it was imperfect. However, Emperor Augustus intervened, ordering Virgil's literary executors, Lucius Varius Rufus and Plotius Tucca, to disregard this wish. Instead, Augustus commanded that the epic be published with as few editorial changes as possible, recognizing its immense cultural and political significance.

Consequently, the existing text of the Aeneid may contain elements that Virgil intended to refine. While there are a few lines that are indeed metrically unfinished, some scholars argue that Virgil may have intentionally left these for dramatic effect. Other alleged imperfections are subjects of ongoing scholarly debate, contributing to the complex and multi-layered interpretations of the epic.

4. Thought and Literary Style

Virgil's works are permeated by a rich tapestry of philosophical thought and are distinguished by a highly refined and influential literary style.

Throughout his poetry, especially the Georgics and Aeneid, Virgil engages with various philosophical currents of his time. While influenced by the Epicurean teachings he studied in his youth, which advocated for peace of mind and detachment from political turmoil, his later works show a clear inclination towards Stoicism. This shift is evident in the Aeneid's emphasis on duty (*pietas*), fate, and the suppression of personal emotion for a greater cause, particularly in the character of Aeneas. Aeneas's struggles and ultimate sacrifice of personal happiness for the destined foundation of Rome reflect Stoic ideals of resilience and adherence to a divine plan.

Virgil's nationalistic perspective on Rome's greatness and destiny is a pervasive theme, particularly in the Aeneid. He crafts a powerful foundation myth that connects Rome to the heroic age of Troy, presenting the city's rise as a divinely ordained mission. The epic is replete with prophecies and historical allusions that link Aeneas's journey to the future glory of Rome and the reign of Augustus, thereby legitimizing the new imperial order. However, this nationalistic fervor is often tempered by a profound sense of human suffering and the heavy cost of empire, suggesting a complex and often ambiguous view of Rome's destiny.

Stylistically, Virgil's poetry is renowned for its elegance, musicality, and intricate craftsmanship. He meticulously employed dactylic hexameter, refining it to an unprecedented level of sophistication and flexibility. His narrative techniques include:

- Intertextuality**: Virgil frequently alludes to and subtly reworks themes, lines, and episodes from earlier Greek and Latin authors, especially Homer, Ennius, and Apollonius of Rhodes, creating layers of meaning and engaging in a dialogue with literary tradition.

- Allusion and Symbolism**: His poems are rich with subtle allusions to contemporary political events, Roman history, and mythology, often employing complex symbolism that allows for multiple interpretations.

- Pathos and Psychological Depth**: Despite the epic grandeur, Virgil excels at portraying the internal struggles and emotional complexities of his characters, particularly Aeneas and Dido, evoking deep empathy from the reader. His ability to convey human suffering and loss even amid triumph contributes to the poem's unique tone.

- Descriptive Power**: Virgil's vivid and evocative descriptions, whether of landscapes in the Eclogues and Georgics or battles in the Aeneid, create immersive and memorable imagery.

- Ambiguity**: A distinctive feature of his style, particularly in the Aeneid, is its pervasive ambiguity. The ending, with Aeneas's merciless killing of Turnus, leaves readers with questions about the nature of heroism and the morality of violence, reflecting a nuanced, sometimes pessimistic, undercurrent beneath the celebratory facade. This ambiguity contributes to the work's enduring appeal and its capacity to resonate with diverse critical interpretations, including those from a pacifist perspective.

5. Legacy and Reception

Virgil's works profoundly shaped Western literature, art, and thought for millennia, securing his status as one of the most influential poets in history.

5.1. In Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Almost immediately upon their publication, Virgil's works revolutionized Latin poetry. The Eclogues, Georgics, and especially the Aeneid rapidly became standard texts in Roman school curricula, familiar to all educated citizens. Subsequent Roman poets frequently engaged with Virgil's works intertextually, building upon his themes and stylistic innovations. Ovid, for instance, parodies the opening lines of the Aeneid in his Amores and offers a "mini-Aeneid" in Book 14 of his Metamorphoses, showcasing a significant post-Virgilian response to the epic genre. Lucan's epic, Bellum Civile, is often seen as an "anti-Virgilian" epic, deliberately departing from Virgilian conventions by omitting divine intervention and focusing on historical events. The Flavian-era poet Statius, in his 12-book epic Thebaid, openly acknowledged Virgil's supremacy, advising his own poem "not to rival the divine Aeneid, but follow afar and ever venerate its footsteps." Silius Italicus was another ardent admirer, with nearly every line of his epic Punica referencing Virgil, even acquiring Virgil's tomb and venerating him.

Virgil also gained early commentators, such as Servius (4th century AD), whose work drew upon Donatus. Servius's commentary provided valuable information about Virgil's life and sources, though modern scholars sometimes find its interpretations simplistic.

5.1.1. Magician Legends and Christian Interpretations

During the Middle Ages, Virgil's reputation evolved significantly, leading to numerous legends associating him with magic and prophecy. This transformation was partly fueled by the "Messianic" Fourth Eclogue, which describes the birth of a boy ushering in a golden age. From at least the 3rd century, Christian thinkers interpreted this eclogue as a premonition of Jesus's birth. Consequently, Virgil came to be seen as a precursor to Christianity, on a par with the Hebrew prophets of the Bible, lending him an aura of divine foresight.

The concept of the Sortes Vergilianae ("Virgilian Lots") emerged, where random passages from Virgil's poetry were chosen and interpreted for divination, a practice that persisted from the time of Hadrian into the Middle Ages. Macrobius, in his Saturnalia, lauded Virgil's work as the embodiment of human knowledge and experience, akin to the Greek reverence for Homer.

Beyond prophecy, Virgil was increasingly portrayed as a powerful magician. Legends about his magical abilities became widespread from the 12th century onward, particularly around Naples. These stories, sometimes called "Virgil in his basket" as part of the Power of Women literary topos, depicted him as capable of performing various feats of magic, such as creating a bronze fly statue to keep flies out of Naples or being humiliated by a woman who left him suspended in a basket for public ridicule. Medieval Welsh folklore even saw his name, Fferyllt or Pheryllt, become a generic term for a magic-worker, surviving in the modern Welsh word for pharmacist. The Jewish Encyclopedia also suggests that medieval legends about the golem might have been inspired by Virgilian tales of the poet's supposed power to animate inanimate objects. These legends highlight how Virgil's literary prestige morphed into a popular image of a supernatural figure in the medieval imagination.

5.2. In the Renaissance and Early Modern Era

The Renaissance witnessed a profound resurgence of interest in Virgil, establishing him as a primary model for epic poets. Edmund Spenser self-consciously styled himself as the "English Virgil," and John Milton's epic Paradise Lost was deeply influenced by the structure and themes of the Aeneid.

Perhaps one of the most significant testaments to Virgil's enduring influence is his prominent role in Dante's monumental Divine Comedy. In this allegorical epic, Virgil serves as Dante's wise and revered guide through the realms of Hell and the greater part of Purgatory. Dante explicitly pays homage to Virgil, proclaiming, "thou art alone the one from whom I took the beautiful style that has done honour to me." This portrayal solidified Virgil's image as a moral and literary authority for centuries.

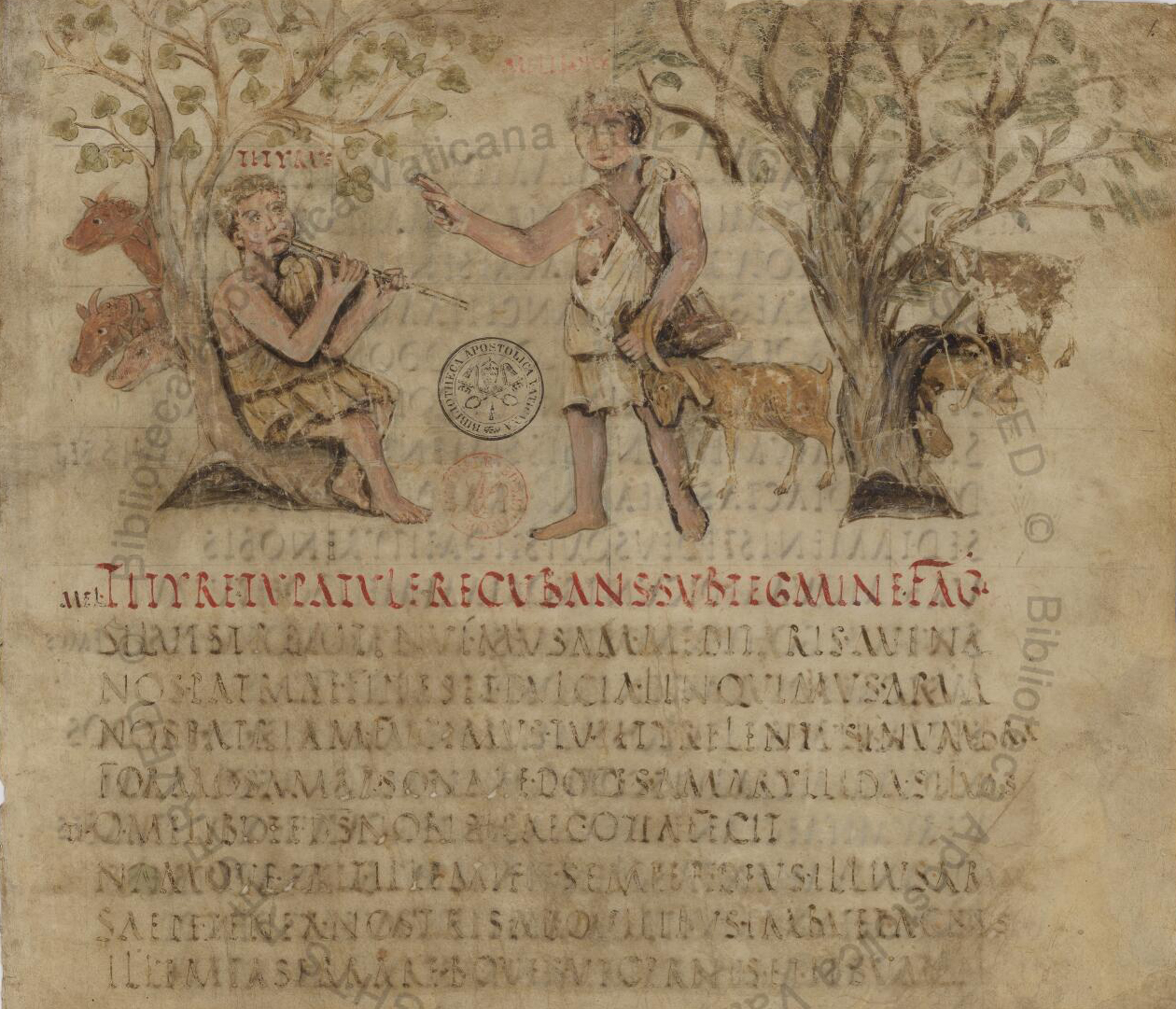

Virgil's inspiration continued into the modern era, influencing artists such as Hector Berlioz, whose opera Les Troyens adapts the Aeneid, and the novelist Hermann Broch, whose novel The Death of Virgil explores the poet's final moments. His works, particularly the Eclogues, also set the foundation for the concept of Arcadia as an idealized, timeless pastoral retreat in Western literature and art, and the Georgics laid the groundwork for environmental and agricultural themes in poetry. The preservation of his works through manuscripts like the 5th-century Vergilius Romanus, Vergilius Augusteus, and Vergilius Vaticanus further ensured his widespread influence.

5.3. Critical Interpretations of the Aeneid

Critical interpretations of the Aeneid have been diverse and often contested, particularly regarding its overall tone and its relationship with the Augustan regime. Some scholars view the poem as fundamentally pessimistic and subtly subversive to Augustus's political agenda, highlighting the sacrifices and human cost of empire. Others interpret it as a celebratory epic, glorifying the new imperial dynasty and Rome's divinely ordained destiny, seeing strong parallels between Augustus as the re-founder of Rome and Aeneas as its mythical founder. The poem's strong teleology, or forward drive towards a destined climax, with its numerous prophecies about Rome's future, Augustus's deeds, and the Punic Wars, supports this celebratory view. The shield of Aeneas, depicting Augustus's victory at Actium against Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII, further underscores the connection to imperial propaganda.

Another significant focus of study is the complex character of Aeneas. As the protagonist, Aeneas often appears to waver between his personal emotions and his unwavering commitment to his prophetic duty to found Rome. Critics note the breakdown of Aeneas's emotional control in the final sections of the poem, particularly his merciless slaughter of Turnus despite pleas for mercy. This act, by the otherwise "pious" and "righteous" Aeneas, has generated considerable debate. Post-Vietnam War interpretations, particularly in the 20th century, often adopt a pacifist perspective, arguing that Aeneas's final violent act reflects Virgil's underlying critique of war and its brutalizing effects, rather than a simple celebration of Roman victory. This unresolved ambiguity at the epic's conclusion contributes significantly to its enduring critical engagement and its ability to provoke varied scholarly discussions.

The Aeneid was an immediate success upon its publication. It is famously reported that Virgil recited portions, including Books 2, 4, and 6, to Augustus himself. Book 6, particularly the passage mourning the early death of Marcellus, Augustus's nephew, supposedly caused Augustus's sister, Octavia the Younger, to faint. While the historical accuracy of this anecdote is debated, it has served as a powerful basis for later art, such as Jean-Baptiste Wicar's painting Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus, Octavia, and Livia.

6. Monuments and Commemorations

Virgil's enduring legacy is also commemorated through various physical monuments and associated places.

The most famous site connected to Virgil is his supposed tomb in Naples, Italy. Located at the entrance of an ancient Roman tunnel (the *grotta vecchia*) in the Piedigrotta district, near the Mergellina harbor, this site has been a destination for pilgrims and travelers for centuries. Although the exact location of his burial has been debated, this particular tomb, with its associated inscription, became a focal point of veneration in the Middle Ages and continues to attract visitors as a significant cultural landmark.

Beyond his tomb, various statues and memorials dedicated to Virgil can be found, particularly in Italy. For example, a statue of Virgil stands prominently in Mantua, his birthplace, celebrating his connection to the region. These monuments serve not only as tributes to his literary genius but also as reminders of his profound and lasting impact on Western civilization.