1. Early Life and Background

Jacques Anquetil's journey into professional cycling began in Normandy, France, where he was born and spent his formative years.

1.1. Childhood and Education

Anquetil was born on 8 January 1934, in a clinic in Mont-Saint-Aignan, a suburb of Rouen in Normandy. His parents were Ernest and Marie, and he had a younger brother named Philippe. His father, Ernest, was the grandson of a Prussian soldier named Ernst, who died in the Franco-Prussian War after an affair with Melanie Grouh, Ernest's grandmother. Melanie later married Frédéric Anquetil, who adopted her son Ernest Victor, Jacques' grandfather, who died in World War I, leaving Jacques' father Ernest as the head of the family at age 11. His mother, Marie, had been orphaned at age 2 and raised by nuns.

Anquetil received his first bicycle from his father at the age of four. In 1941, his father, a builder, refused work contracts for German occupying forces, leading to a lack of work. The family moved to Le Bourguet, near Quincampoix, to become strawberry farmers. There, young Anquetil attended school, excelling particularly in mathematics. His father's violent behavior after excessive alcohol consumption led his mother to move to an apartment in Paris, leaving her sons with their father. At 11, needing a new bike as his second one became too small, Anquetil successfully argued to replace a worker on the strawberry fields, earning enough money to buy a Stella bicycle.

At 14, he began attending Technical College in Rouen's southern district of Sotteville to become a metalworker. There, he met Maurice Dieulois, an amateur cyclist whose father presided over the local cycling club, AC Sottevillais. Through Dieulois, Anquetil joined the club in late summer 1950, under the guidance of André Boucher. Boucher recognized Anquetil's talent, providing him with two bikes (one for training, one for races), free tires, maintenance, and a performance bonus. By the end of 1950, Anquetil earned his diploma and, by January 1951, took a job in a Sotteville workshop for a meager 64 FRF an hour. When his employer refused him Thursday evenings off for club training, he quit in early March, returning to work on his father's farm to pursue cycling.

1.2. Amateur Career

Anquetil's amateur racing debut was on 8 April 1951, in Le Havre. While his friend Dieulois won, Anquetil finished in the main group. He secured his first victory in his fourth race, the Grand Prix Maurice Latour, on 3 May of the same year. He went on to win eight races that season, including the Normandy team time trial championships in July. The season concluded with his first individual time trial, which was also the final race of the season-long maillot des jeunes competition. Starting last as the competition leader, four minutes behind Dieulois, Anquetil initially hesitated to overtake his friend but eventually did, winning both the race and the overall competition.

In his second amateur season in 1952, Anquetil moved from junior to senior ranks, achieving eleven victories and five additional podium finishes. During the regional championship race for Normandy, rival riders from the powerful Caen cycling club closely marked him. Frustrated by their tactics 75 mile (120 km) from the finish, Anquetil considered retiring. However, Boucher urged him on. Anquetil then feigned untying his toe-straps, dropping back in the group, leading his opponents to believe he would abandon. He then launched a surprise attack from the back, leaving the competition behind, bridging a five-minute gap to the leading group, and ultimately winning the race. He also dominated the Grand Prix de France time trial, winning by a significant 12-minute margin. His first national appearance was at the qualification event for the 1952 Summer Olympics, where he finished third. Shortly after, he won the French amateur championships in Carcassonne, securing his place on the French squad for the Helsinki Olympic Games. On 3 August, he placed twelfth in the road race but performed better in the team race, earning a bronze medal alongside Alfred Tonello and Claude Rouer. He then competed in the amateur road race at the 1952 UCI Road World Championships in Luxembourg, featuring future stars like Charly Gaul and Rik van Looy. The flat course did not suit Anquetil, and he finished in the main bunch, ranked equal eighth.

For his final amateur season in 1953, Anquetil obtained an "independent" license, a category for riders transitioning between amateur and professional status, which was abolished in 1966. This allowed him to compete against young professionals. After winning the independent championship of Normandy, his first race against professional competition was the three-stage Tour de la Manche in August. He finished second on the first stage, 24 seconds behind future World Champion Jean Stablinski. The following day, Anquetil won the 24 mile (38.6 km) time trial by almost 2 minutes, taking the race lead. On the final stage to Cherbourg, rival teams attempted to dislodge him, even forcing him into a ditch. Maurice Pelé, another independent rider, disapproved of their tactics and helped Anquetil rejoin the group. Anquetil finished safely in the peloton, winning the overall race. In the amateur category, Anquetil was leading the season-long maillot des As competition, run by the newspaper Paris-Normandy. The final race, a 76 mile (122 km) time trial on 23 August 1953, saw Anquetil win by a remarkable nine minutes over second-placed Claude Le Ber, at an average speed of 26 mph (42.05 km/h), an unprecedented speed for an amateur. This prompted journalist Alex Virot from Radio Luxembourg to quip, "In Normandy there can only be 900 metres in a kilometre!". Following this exploit, Anquetil was invited to the Circuit de l'Aulne, France's most prestigious criterium race, which that year included Tour de France winner Louison Bobet. Anquetil finished in the leading group but was held by his jersey by an unknown rider during the final sprint, preventing him from victory, which went to Bobet.

2. Professional Career and Achievements

Jacques Anquetil's professional career was marked by groundbreaking achievements, intense rivalries, and a strategic approach that redefined Grand Tour racing.

2.1. Early Career and Grand Prix des Nations

Following his success at the Tour de la Manche, Anquetil received offers from several professional teams. Francis Pélissier, a former professional and sporting director of the La Perle team, offered him a contract to race in the Grand Prix des Nations in September 1953. This event was then considered the world's most prestigious time trial, often called the "unofficial world championship" for time trialists. As a minor, Anquetil needed his parents' consent to sign the two-month contract, which paid him 30.00 K FRF per month. This contract briefly caused conflict with his coach Boucher, who threatened legal action, but they reconciled in time for Boucher to assist Anquetil's race preparation.

The Grand Prix des Nations, held on 27 September, covered 87 mile (140 km) from Versailles to the Parc des Princes in Paris. Anquetil meticulously prepared, even sending himself postcards from various points along the route to describe the course. On race day, he started strongly despite a puncture and a bike swap within the first few kilometers. He ultimately won the time trial by a margin of almost seven minutes over Roger Creton. At just 19 years old, he came within 35 seconds of breaking the track record set by Hugo Koblet two years prior. This victory made Anquetil an instant sensation in the sports press, with Tour de France director Jacques Goddet publishing an article in L'Equipe titled: "When the Child Champion was Born."

Three weeks later, Anquetil secured another victory at the Grand Prix de Lugano in Switzerland. He was then invited to ride the prestigious Trofeo Baracchi, a two-man time trial in Italy. En route, Anquetil visited his idol, Fausto Coppi, then considered the era's best cyclist. Both competed in the Trofeo Baracchi, with Coppi winning alongside Riccardo Filippi. Anquetil and his partner, experienced rider Antonin Rolland, finished second. Rolland later remarked, "I was well prepared and in very good form. Nevertheless, Jacques assassinated me and for the last 30 kilometers I could not go through; I was clinging on by the skin of my teeth."

2.2. Military Service and Hour Record Attempt

Anquetil's first full professional season in 1954 began with the week-long Paris-Nice stage race. At 20, he won the time trial stage and finished seventh overall. Despite no victories, strong results secured him a spot on the French team for the World Championships in Solingen. 28 mile (45 km) from the finish, Anquetil was part of an elite front group including Bobet, Coppi, and Gaul. Though Anquetil soon dropped back, Bobet won the world title, and Anquetil finished a credible fifth, ahead of Coppi. Throughout the season, tensions grew between Anquetil and Pélissier, who felt Anquetil lacked discipline regarding diet and alcohol. When Pélissier chose to follow Hugo Koblet during that year's Grand Prix des Nations, Anquetil was enraged by this perceived lack of trust. On race day, he comprehensively beat Koblet. At the finish, Anquetil ignored Pélissier, drove to Pélissier's café outside Paris, and delivered the winner's bouquet to his director's wife.

Following an eleventh-place finish at Paris-Tours, Anquetil began his compulsory 30-month military service. He was transferred to the sportsman's battalion at Joinville, which allowed him significant freedom to train and continue his cycling career. At the Trofeo Baracchi, Anquetil partnered Bobet, but with only three hours of sleep and a late arrival in Italy, they finished second, again to Coppi and Filippi.

The 1955 season was the last for the La Perle team due to dwindling funds. In the spring, Anquetil finished 14th at Paris-Roubaix after a chain break and was forced to abandon the Critérium National after a crash. He gained more experience by placing 15th at the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré. At the French National Road Race Championships, he supported his teammate André Darrigade to beat Bobet for the title. Towards the season's end, Anquetil won the national individual pursuit championship on the track, finished sixth in the world championship road race, and secured a third consecutive victory at the Grand Prix des Nations.

Momentum in the press had been building, urging Anquetil, known for his time trial prowess, to attempt to break Coppi's hour record for the longest distance covered in an hour, set in November 1942. Anquetil eventually announced his attempt for 22 October 1955, at the Velodromo Vigorelli in Milan. He started at a very high speed, quickly outpacing Coppi's split times, but eventually slowed and grew exhausted, failing to break the record by 1969 ft (600 m). His final race of the season was again the Trofeo Baracchi, this time partnered with Darrigade, but they finished second to Coppi and Filippi once more.

Due to the ongoing Algerian War, every military service included a six-month stint in Algeria, which Anquetil had to begin in the second half of 1956. He decided to make another hour record attempt before his deployment. Prior to this, he won another national pursuit title but had to withdraw from Paris-Nice due to a crash. Now riding for the Helyett team, he won a stage at the Three Days of Antwerp. Anquetil made his second hour record attempt on 25 June, but again starting too fast, he abandoned with five minutes remaining. A third attempt was scheduled just four days later. This time, by maintaining a rigid schedule and avoiding an overly fast start, Anquetil finally succeeded, breaking Coppi's record with a distance of 29 mile (46.159 km), 1020 ft (311 m) further than Coppi's mark.

After setting the record, Anquetil continued his season by earning a silver medal in the individual pursuit at the Track Cycling World Championships. Another victory followed at the Grand Prix des Nations. Anquetil and Darrigade then traveled to Italy to compete for the first time in the Giro di Lombardia, one of cycling's monument classics, a race that Darrigade won. Anquetil was then posted to Algeria, concluding his season.

2.3. First Tour de France Victory (1957)

Anquetil was discharged from the army on 1 March 1957. His first race back was just one day later, at Genoa-Nice, where he finished second in the sprint to Bobet. This was impressive, as Anquetil had gained 22 lb (10 kg) during his military service. It took him one month and 0.7 K mile (1.20 K km) of training to return to his previous weight before starting Paris-Nice. In that race, he won the mountainous stage 5 time trial, which put him into the overall lead, a position he successfully defended until the end. In a last-minute decision, Anquetil again competed at the Track World Championships in the individual pursuit, but lost to eventual champion Roger Rivière.

By this point, Anquetil was considered a potential favorite for the Tour de France, the world's most prestigious cycling race. At this time, Tour riders competed in national teams rather than trade teams. The selection for the French team was challenging for its manager, Marcel Bidot. The previous year's race had been won by a relatively unknown French rider from a regional team, Roger Walkowiak, making him an automatic pick for the national team. Meanwhile, three-time Tour winner Bobet, and his teammate Raphaël Géminiani, were also expected to be selected. Anquetil and Darrigade publicly stated they would only ride if both were selected together. The selection ultimately favored Anquetil when Bobet announced during the Giro d'Italia that he would skip the Tour.

At the Tour, Anquetil was the only debutant on the French team. On stage 1, he was involved in a crash but was safely brought back into the main group. Anquetil's first stage win came on stage 3, finishing in his hometown of Rouen. On stage 5, into Charleroi, Anquetil escaped with another rider and gained the yellow jersey of the general classification leader for the first time in his career. He held the lead for two days, then attacked on stage 9, winning into Thonon-les-Bains to reclaim the yellow jersey, gaining 11 minutes on his principal rivals. Federico Bahamontes, another race favorite, retired on the following rest day due to an intense heat wave. On the first high-mountain stage into Briançon, Anquetil finished fourth, less than two minutes behind stage winner Gastone Nencini and Marcel Janssens, but retained his lead, 11 minutes ahead of Janssens. After some uneventful stages, Anquetil's rivals took advantage of him riding towards the back of the peloton to attack on stage 14, forming a seven-rider lead group, all within the top ten of the general classification. Darrigade dropped back and worked with Anquetil to close the gap. The following day, Anquetil won the time trial at the Montjuïc circuit in Barcelona to extend his overall lead. He lost small amounts of time on stage 18 but rebounded to win the stage 20 time trial, sealing his first Tour de France victory. His eventual winning margin over Janssens was almost 15 minutes. At 23, he was the youngest Tour winner since the end of World War II.

After the Tour, Anquetil competed in the World Championships in Waregem. The final part of the race was contested by a six-man group comprising three French and three Belgian riders. Rik van Steenbergen won the sprint ahead of Bobet and Darrigade, with Anquetil finishing sixth. He then won the Grand Prix des Nations again, beating Ercole Baldini. At the Six Days of Paris, he competed on the track with Darrigade and Italian Ferdinando Terruzzi, winning the event.

2.4. Challenges and Setbacks (1958-1959)

Anquetil faced significant challenges and setbacks in the years immediately following his first Tour de France victory, particularly in 1958 and 1959.

2.4.1. 1958: Année Terrible

In 1958, Anquetil started his season slowly. He won the time trial stage at Paris-Nice in March but only finished tenth overall, the same position he achieved at Milan-San Remo a couple of days later. After finishing twelfth at the Critérium National, he targeted Paris-Roubaix, a race he felt suited him. Still 124 mile (200 km) from the finish, he launched an attack, creating a 17-rider lead group, which quickly dwindled to just four due to Anquetil's relentless pace. However, the Belgian teams in the peloton never allowed the gap to exceed four minutes. Although Anquetil managed to rejoin the lead group after a puncture 8.1 mile (13 km) from the finish, the group was eventually caught 2.5 mile (4 km) before the line. His failure to win at Roubaix was noted by the public, as it was the first time he had started a classics race with the explicit intention of winning. Anquetil bounced back by winning the Four Days of Dunkirk. In preparation for the Tour de France, he then finished eighth at the national championships.

As the defending champion, Anquetil was the French team's top choice for the Tour de France. However, Bidot could not exclude three-time winner Bobet, leaving the team with two captains. Anquetil agreed but insisted that Bobet's close ally Géminiani be left off the squad. Bidot conceded, and as Bobet did not support Géminiani, their friendship became heavily strained. Géminiani entered the Tour as the leader of the Centre-Midi regional team and seized every opportunity to attack the main French squad. After an uneventful start, Géminiani attacked on stage 6, gaining ten minutes on Anquetil. Two days later, during the Tour's first time trial, Anquetil suffered another blow when Charly Gaul, typically known more as a climber than a time trialist, managed to beat Anquetil in his favored discipline, albeit by just seven seconds. On stage 18, a mountain time trial up Mont Ventoux, Anquetil lost over four minutes to Gaul. While he had predicted such a result before the Tour, as the climb suited Gaul more, it was still a significant loss given the time Anquetil had already conceded. Géminiani, meanwhile, did enough to secure the yellow jersey and gained more time on the following stage due to an untimely mechanical issue for Gaul. Heading into stage 21 to Aix-les-Bains, Géminiani led the overall standings, Anquetil was third, 7:57 minutes behind, while Gaul was fifth, over 15 minutes adrift. The stage featured five climbs, on the second of which Gaul attacked in rainy and cold conditions. Anquetil followed, only two minutes behind Gaul at the foot of the next climb, the Col de Porte. The weather then affected Anquetil, who had chosen to wear a light silk jersey instead of wool. He lost 22 minutes by the end of the stage and developed a chest infection. Géminiani fared little better, losing 15 minutes to Gaul, who would go on to win the Tour after winning the final time trial. Even with his infection, Anquetil decided to start the following stage to help the French team win the team classification, but after coughing up blood, he was hospitalized with a 105.08000000000001 °F (40.6 °C) fever and forced to abandon.

Anquetil took time to recover from his infection. He later described this period as the lowest point in his career, even contemplating retirement, but ultimately continued. The illness still hampered his efforts at the World Championships in Reims, where he abandoned. He recovered to win three end-of-season time trials: the Grands Prix in Geneva and Lugano, and the Grand Prix des Nations for the sixth consecutive time. He then finished twelfth at both Paris-Tours and the Giro di Lombardia before ending the road season with a second-place finish at the Trofeo Baracchi. On the track, Anquetil, Darrigade, and Teruzzi successfully defended their title at the Paris Six-Days, concluding the year at the Vélodrome d'Hiver for the last time the event was held there. Anquetil's biographer Paul Howard later described 1958 as his année terrible ("terrible year").

2.4.2. 1959: Failed Attempt at the Giro-Tour Double

By early 1959, Roger Rivière had emerged as a serious challenger to Anquetil. Rivière had not only beaten Anquetil to become World Champion in the individual pursuit but also broke Baldini's hour record and later improved it again, becoming the first man to cover over 29 mile (47 km) in an hour. The two riders first faced each other on the road at the 1959 Paris-Nice, which that year was called Paris-Nice-Rome, ending in Rome. Neither rider won, and Rivière finished higher in the overall classification, but Anquetil's teammate Jean Graczyk took the victory, and Anquetil was faster in the time trial.

For 1959, Anquetil set a goal to emulate his idol Fausto Coppi by winning both the Giro d'Italia and the Tour de France in the same year. Gaul, who had previously won the Giro in 1956, was also competing. Anquetil started the Giro strongly, taking the race leader's pink jersey after a short time trial on stage 2. He lost his lead to Gaul the following day on a hilltop finish. Gaul increased his advantage on stage 7 by winning the mountain time trial up Mount Vesuvius, extending his lead over second-placed Anquetil to 2:19 minutes. Anquetil managed to gain back 22 seconds on Gaul the next day in another time trial. During stage 12, which featured three ascents of Monte Titano in San Marino, he managed to distance Gaul, gaining one-and-a-half minutes and reducing his deficit to just 34 seconds. On stage 15, Anquetil escaped with several other riders on a downhill section and gained another two-and-a-half minutes on Gaul, reclaiming the pink jersey. While leading the race, Anquetil then won the stage 19 time trial to Susa. Riding at an average speed of 30 mph (47.713 km/h) (faster than Rivière's hour record speed), Anquetil still only gained 2:01 minutes on Gaul, who had started his effort one-and-a-half minutes ahead of Anquetil and had clung on to limit his losses after Anquetil passed him. After the time trial, Anquetil led Gaul by 3:49 minutes in the overall standings. The decisive stage came on stage 21 to Courmayeur, where Gaul attacked on the Col du Petit-Saint-Bernard and ultimately arrived at the stage finish almost ten minutes ahead of Anquetil to secure overall victory. Anquetil finished the Giro in second place, 6:12 minutes behind Gaul.

For the Tour de France, the French national team started with four potential contenders for overall victory: Anquetil, Bobet, Géminiani, and Rivière. While the latter two were riding on the same trade team and got along well, there was little sympathy and cooperation among the other riders. Bobet retired from what would be his last Tour on top of the Col de l'Iseran, while Géminiani was significantly weaker than the previous year and posed no threat for overall victory. The French team's main challengers came from Gaul, Spain's Federico Bahamontes, Italian Ercole Baldini, and Henry Anglade, a Frenchman riding on the Centre/Midi regional team. The first notable stage for the general classification was the stage 6 time trial, won by Rivière, 21 seconds ahead of Baldini and almost a minute faster than Anquetil. The following day, Anglade was part of a breakaway that gained nearly five minutes on the rest of the field. On stage 13, Anglade won ahead of Anquetil, with Baldini and Bahamontes also in the lead group. Gaul struggled on the stage and lost twenty minutes, effectively ruling him out of contention. Anglade was now second in the overall standings, over three minutes ahead of Baldini, Bahamontes, and Anquetil, while Rivière was over six minutes behind Anglade. Two days later, Bahamontes won the mountain time trial up the Puy de Dôme, taking over three minutes from Anglade's lead. Anquetil was now sixth in the standings, over five minutes behind second-placed Bahamontes. On stage 17 in the Alps, Bahamontes and Gaul escaped together; Gaul took the stage win while Bahamontes moved into the race lead, finishing three-and-a-half minutes ahead of the other challengers. The next stage was the decisive one, featuring several high mountain climbs. Following the Col de l'Iseran, Anquetil and Rivière found themselves in a lead group, having distanced Bahamontes and Gaul, but then allowed them to catch back on. On the descent of the following climb, the Col du Petit-Saint-Bernard, Anglade, Baldini, and Gaul attacked. Anquetil and Rivière both assisted Bahamontes in regaining contact with the others. Baldini would win the stage while Bahamontes remained in the lead, 4:04 minutes ahead of Anglade, who lost another minute the following day. In the time trial on the penultimate stage to Dijon, Rivière again won ahead of Anquetil, beating him by 1:38 minutes, while Bahamontes sealed overall victory. As the French riders entered the Parc des Princes during the final stage, they were booed by the crowd, who felt that Anquetil and Rivière had colluded with Bahamontes against their fellow Frenchman, Anglade. This decision might have been influenced by the fact that if another French rider had won the Tour, Anquetil's market value for participation money in the lucrative post-Tour criteriums would have been less. Anquetil made no secret that he embraced the hostile reaction of the crowd, later naming a boat he owned Sifflets '59 ("The Whistles of '59"). Anquetil eventually finished the Tour third overall, 17 seconds ahead of fourth-placed Rivière.

At the World Championships in Zandvoort, Anquetil finished ninth as his friend Darrigade won the title. In early September, he won the prestigious Critérium des As, a race run behind dernys. Anquetil ended his season with victories at the Grand Prix Martini and Grand Prix de Lugano time trials, but for the first time since his first victory in 1953, he did not compete in the Grand Prix des Nations, which was won by Aldo Moser ahead of Rivière. At the Trofeo Baracchi, Anquetil, paired with Darrigade, finished only third after missing the start time by over a minute, and they were also outridden by the pairing of Moser and Baldini.

2.5. Dominance: Tour de France 4-year consecutive wins and 5th win

Anquetil's career reached its peak with his unprecedented consecutive victories in the Tour de France, solidifying his status as a cycling icon.

2.5.1. 1960: Giro d'Italia Success

Following two years without a major stage race victory and with Rivière proving his match in time trials, Anquetil's star seemed to be fading at the beginning of 1960. Not wanting to share leadership of the French team with Rivière, Anquetil chose to focus solely on the Giro d'Italia that year. At Paris-Nice, in the team time trial on stage 2, Anquetil, who suffered mechanical issues, was dropped by his teammates and lost four-and-a-half minutes on his principal rivals. On stage 4, a large breakaway got clear, and Anquetil's team decided not to organize a chase. This allowed the leading group to finish over 23 minutes ahead of the field, making it virtually impossible for anyone not in it to compete for overall victory. Anquetil's poor form was further highlighted when he finished only fourth in the time trial on stage 6b, and he retired the following day. He then finished third at the Critérium National before coming in fourteenth at the Tour of Flanders.

In the first time trial of the Giro d'Italia, Anquetil finished second but then capitalized on a breakaway he was part of on stage 3 to take the overall lead. Anquetil then led the chase to Jos Hoevenaers, who had been part of a breakaway on stage 6. In the long time trial of the race on stage 14, Anquetil retook the lead, finishing 1:27 minutes ahead of Baldini and over six minutes on Gaul. His speed was so fast that if the organizers had applied the usual rules, 70 riders would have missed the time cut; however, the rules were loosened, and only two riders were eliminated. Ahead of the final mountain stages, Anquetil now led Nencini by 3:40 minutes, with Gaul in fifth, 7:32 minutes behind. Stage 20 included the Gavia Pass for the first time in the race's history. On the ascent, Nencini managed to establish a gap on Anquetil after the latter had a flat tire. More punctures and three bike changes followed on the dangerous descent, jeopardizing Anquetil's race lead. He teamed up with Agostino Coletto, whom he offered money to help him in the chase effort, to limit his losses. At the finish in Bormio, Gaul won ahead of Nencini, with Anquetil losing only 2:34 minutes and retaining the pink jersey by 28 seconds. Following a ceremonial final stage, Anquetil arrived in Milan as the winner of the Giro for the first time.

In Anquetil's absence, Rivière competed in the 1960 Tour de France as leader of the French team and was well placed when, on stage 14, he crashed while trying to follow Nencini on a steep descent. He fell 33 ft (10 m) down a ravine and broke two vertebrae, immediately ending his career. The great rivalry with Anquetil thus ended abruptly. Paul Howard later wrote that with Rivière's accident, "by late 1960 Anquetil was temporarily free from a serious adversary, at least within French cycling circles."

At the World Championships in East Germany, Anquetil arrived with little preparation but still managed to finish ninth. Another strong time trial performance followed at the Grand Prix de Lugano, where Anquetil was so fast that second-placed rider Gilbert Desmet owed his position to the fact that Anquetil overtook him and he followed him into the finish. He followed this up with another victory at the Critérium des As, breaking the record speed in the process. Having attacked 6.2 mile (10 km) into the race to test his legs, Anquetil decided he felt so good that he did not slow down and rode alone until the finish.

2.5.2. 1961: Tour de France Return

In early 1961, Anquetil took victory at Paris-Nice. At the Critérium National, he attacked with 0.9 mile (1.5 km) left to go and won ahead of Darrigade, who had switched teams to Alcyon-Leroux. It was Anquetil's first ever victory at a one-day road race. He then competed in the Tour de Romandie, winning the time trial and finishing tenth overall, in preparation for the Giro d'Italia.

At the Giro, Anquetil won the time trial on stage 9 and gained the pink jersey the following day, when he was part of a breakaway that reached the finish ahead of previous leader Guillaume van Tongerloo. On stage 14, a seven-rider breakaway got away, which included Arnaldo Pambianco, who was third overall. At the finish, they had a 1:42 minute advantage on the peloton containing Anquetil, putting Pambianco into the lead. Anquetil then lost another twenty seconds on stage 17 before the race reached the high mountains. On the decisive stage 20, which featured the climbs of the Penser Joch and the Stelvio Pass, Gaul won two minutes ahead of Pambianco, with Anquetil losing another three minutes (two of which were in time bonuses). Therefore, Pambianco won the Giro, 3:45 minutes ahead of Anquetil.

At the National Championship race before the Tour, Anquetil finished fourth, with the title going to Raymond Poulidor, who had earlier in the year won Milan-San Remo. Poulidor would emerge as Anquetil's new main rival, but was left out of the French team for the upcoming Tour de France as his team manager Antonin Magne did not want him to have to work for Anquetil. The Tour began in Anquetil's hometown of Rouen, and before the start, he announced that he planned to hold the race lead from the first day until the end. There were two stages run on the first day: a road stage to Versailles in the morning and then a time trial in the afternoon, with the yellow jersey only being awarded at the end of the day. Anquetil already got in the winning breakaway on the first stage, won by Darrigade, and then in the afternoon, he won the time trial by over three minutes from the rider in second place to move into the overall lead. Over the course of the race, Anquetil rode very passively, only chasing down attacks and limiting his losses, but never going on the attack himself. This led to a race that was considered dull by the public, with sales numbers of the organizing newspaper L'Equipe decreasing as the Tour progressed. Anquetil won the time trial on stage 19 to effectively seal his second Tour de France victory, finishing the course almost three minutes faster than second-placed Gaul. On the final stage into Paris, he attacked together with teammate Robert Cazala, who won the stage. Guido Carlesi used the same breakaway to distance Gaul and take over second place. Anquetil's winning margin over him was 12:14 minutes. Due to what the spectators considered a lack of excitement during the race, Anquetil was booed when they arrived at the Parc des Princes.

Following the Tour, Anquetil competed at the World Championships in Bern, finishing in the lead group in 13th place. He then rode the Grand Prix des Nations for the first time since 1958, taking victory in record time and beating second-placed Desmet by over nine minutes. Following victory at the Grand Prix de Lugano, he managed only fifth place at the Trofeo Baracchi, partnered by Michel Stolker, his worst position at the event during his career. Nevertheless, at the end of the season he was honored with the Super Prestige Pernod for the first time, an award given to the best rider of the year based on points given for high positions in prestigious races.

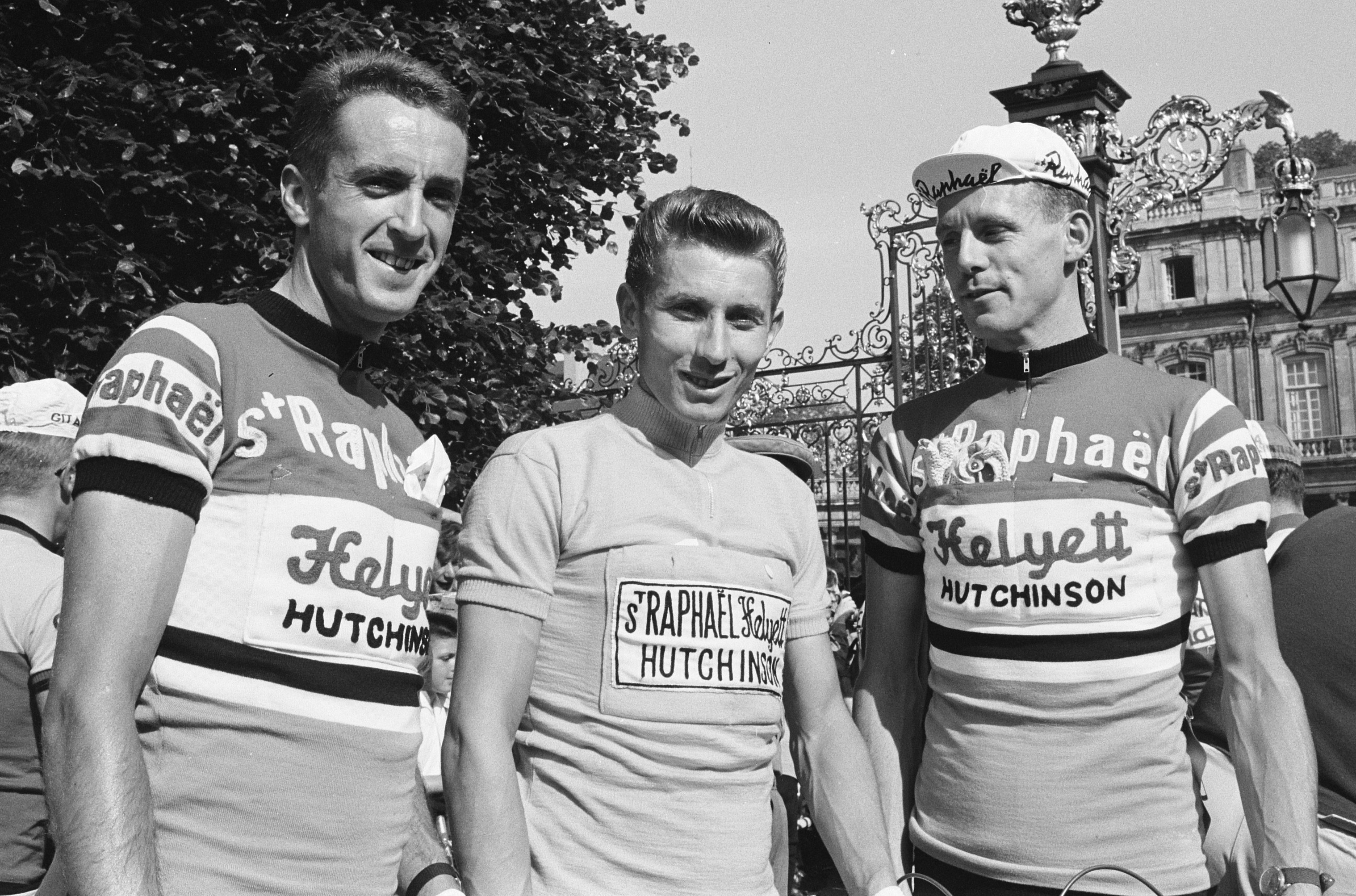

2.5.3. 1962: Third Tour de France Victory

For the new season in 1962, Anquetil's team Helyett folded and merged with the Saint-Raphaël team, whose sporting director was Géminiani, Anquetil's former rival, who had since retired. His early season results were not good, as he had to retire from both Genoa-Nice and Paris-Nice. Anquetil had set himself the goal to become the first rider to have won all three of cycling's Grand Tours, which meant that for 1962, he targeted the Vuelta a España. Here, he had to share team leadership with Rudi Altig. The race came down to the time trial on stage 15, which Altig won decisively. Anquetil then dropped out of the race following the stage, only to be diagnosed with viral hepatitis once back in France. Altig eventually won the Vuelta. Against the advice of his doctor, who felt that the illness had weakened Anquetil too much, he then raced in the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré in preparation for the Tour. He suffered during the fifth stage, where he lost 17 minutes, but managed to finish the race in 12th place overall.

For the 1962 Tour de France, the organizers dropped the provisions of national teams and allowed the riders to compete in trade teams, meaning that Anquetil rode for Saint-Raphaël. Poulidor was considered his main competition along with reigning World Champion Rik van Looy; both were riding their first Tour. A break within the peloton on the first stage, won by Altig, saw Poulidor lose almost eight minutes. Anquetil won the stage 8b time trial and moved into 12th place in the general classification, behind a number of riders who had been in an earlier breakaway but were not considered threats for overall victory. On stage 11, the first in the Pyrenees, van Looy was brought down when a motorbike caused a crash, leading him to abandon. After stage 12, also in the high mountains, Anquetil moved up into sixth place. The following day was a mountain time trial to Superbagnères. Anquetil finished the day third, behind stage winner Bahamontes and Jef Planckaert, the surprise of the Tour, who moved into the race lead, with Anquetil in fourth, 1:08 minutes behind. On stage 19, Poulidor escaped and went on to win the stage, while Anquetil finished with Planckaert, which left their time difference intact. However, Anquetil had moved up to second and Poulidor up to third. In the 42 mile (68 km) time trial on stage 20 to Lyon, Anquetil won with ease, catching Poulidor for three minutes at the half-way mark of the course and beating Planckaert by 5:19 minutes. This gave Anquetil a record-equalling third Tour victory, 4:59 minutes ahead of Planckaert, who showed sportsmanship when he did not attack Anquetil when the latter suffered a crash on the final day into Paris. After the Tour, it was discovered that Anquetil had ridden the entire event with a tapeworm.

While recovering from the worm, Anquetil placed only fifteenth at the World Championships in Salò, won by his friend and teammate Jean Stablinski. Still weakened, he then skipped most of the late-season time trials, except for the Trofeo Baracchi, which he attended together with Altig. Not having prepared well for the event, Anquetil suffered from the beginning and was unable to take turns at the front, forced to stay in Altig's slipstream and at some points suffering the humiliation of Altig having to push him in order to keep up. When they reached the finish, their time was taken at the entrance of the velodrome. As they entered the arena, Anquetil was unable to take the sharp right turn onto the track, drove onto the grass, and crashed into a crowd of spectators. The pair had won the event, in record time, but Anquetil was brought into hospital, his face covered in blood, while Altig took the victory lap on his own. Feeling humiliated by the experience, Anquetil prepared well for a similar two-man time trial event two weeks later in Altig's home country, in Baden-Baden. This time, it was Anquetil who set a high pace which Altig had a hard time following.

2.5.4. 1963: Vuelta-Tour Double

Early in 1963, Anquetil won Paris-Nice and the Critérium National in preparation for another attempt at the Vuelta. He lined up at the 1963 Vuelta a España in good shape. He won the stage 1b time trial on the first afternoon by 2:51 minutes on the second-placed rider, including the time bonus, he already held over three minutes advantage on his rivals. Anquetil's team managed to neutralize all the attacks during the difficult first week. The remaining stages were mostly flat and suited Anquetil. Even though he only finished second on the stage 12b time trial to Tarragona, suffering from stomach cramps, he eventually won the Vuelta easily, beating José Martín Colmenarejo by 3:06 minutes. With his victory, he became the first rider to have won all the Grand Tours.

To prepare for the Tour, Anquetil competed in the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré, where he won the time trial and the general classification. Thereafter, he helped Stablinski to victory at the National Championships, himself finishing third. The Tour de France became a fight between Anquetil and Bahamontes, who gained time when he got into a breakaway on the first stage. After winning the stage 6b time trial, Anquetil moved up into seventh place overall, behind a number of riders who had been in earlier breakaways, but over a minute ahead of Bahamontes and Poulidor. On stage 10, he managed to stay with Bahamontes and outsprinted him at the finish, gaining his first-ever victory on a mountain stage. On stage 17, Anquetil and Géminiani used a ruse, pretending to suffer a broken chain, to allow Anquetil to switch to a lighter bike for the ascent of the Col de la Forclaz, enabling him to stay with Bahamontes on the steep climb and again outsprint him at the finish. He had therefore moved into the race lead, extending his advantage in the final time trial. His eventual winning margin over Bahamontes was 3:35 minutes as he became the first rider to win the Tour four times.

At the World Championship road race in Ronse, Anquetil was leading alone with 0.6 mile (1 km) ahead of the chasing field, but eased his effort when he turned around to see the other riders approaching. After the finish, second-placed van Looy was irritated at Anquetil, stating that he had given up his chance at certain victory. Towards the end of the season, he competed in the Trofeo Baracchi, partnered with Poulidor, where they finished second. For the second time, he won the Super Prestige Pernod for the best rider of the season.

2.5.5. 1964: Giro d'Italia, a Fifth Tour de France, and the Duel with Poulidor

At the beginning of the 1964 season, Anquetil raced at Paris-Nice again, being beaten in the uphill time trial by Poulidor and finishing only sixth. When he lined up for the spring classic Gent-Wevelgem, few expected much of him, since Anquetil did not usually excel at one-day races. A few kilometers before the finish, Anquetil, unfamiliar with the course, asked another rider where the finish was. Given the answer that it was not far away, he broke away from the field for an unlikely victory, his first at a one-day road race outside of France. For 1964, Anquetil had again set himself the target to emulate Coppi by winning the Giro and the Tour in the same year. He started the Giro d'Italia strongly, winning the stage 5 time trial at a speed of over 30 mph (48 km/h), taking the race lead in the process. Though he was unable to add another stage victory, he would not lose the pink jersey until the finish in Milan, beating Italo Zilioli by 1:22 minutes.

The 1964 Tour de France would become a two-man fight between Anquetil and Poulidor. The latter lost 14 seconds after a crash on the first stage, but took some time back when he escaped in a group on stage 7, with Anquetil reaching the finish 34 seconds behind. The next day, Anquetil lost another 47 seconds, as Poulidor finished second and Anquetil suffered a puncture. On stage 9, finishing in Monaco, Poulidor sprinted for the stage victory and celebrated, only to realize there was another lap to run. The second time around, it was Anquetil who won the stage and with it a one-minute time bonus. The next day, Anquetil also won the time trial, taking another 46 seconds advantage on Poulidor. In the general classification, Anquetil now was second, with Poulidor third, 31 seconds behind. During the rest day in Andorra, Anquetil, known for his extravagant eating habits, was pictured eating a méchoui, an entire lamb. The next day, stage 14, Anquetil started badly, falling behind on the first climb and even contemplating retiring from the race. Being four minutes behind Poulidor, Bahamontes, and yellow jersey Georges Groussard, Anquetil found himself in a group of seven riders who worked well together and succeeded in bridging the gap. Poulidor then had to change bikes with 17 mile (28 km) to go, and fell into the ditch when his director pushed him too hard when he got going again. By the end of the stage, Poulidor had lost 2:37 minutes on Anquetil. Poulidor managed to record a strong solo victory on the following stage into Luchon, gaining enough time to close the gap on Anquetil in the general classification to just nine seconds. In the stage 17 time trial, Anquetil took victory, but Poulidor managed to reduce his losses to just 37 seconds, even though he suffered a puncture and a slow bike change, leaving him 56 seconds down on Anquetil overall. Stage 20 was the decisive leg of the race, ending on the Puy de Dôme climb. Poulidor attacked early in the stage, but was brought back by Anquetil with the help of Altig. As they reached the final climb, Bahamontes and Julio Jiménez escaped, while Anquetil and Poulidor made the ascent side-by-side. In what would become one of the Tour's most historic stages, the two opponents went up the climb elbow to elbow, until 2953 ft (900 m), Anquetil weakened, allowing Poulidor to slowly get ahead of him. By the finish, Poulidor had taken 42 seconds out of Anquetil's advantage, who remained in the yellow jersey. After crossing the finish line, Anquetil asked Géminiani how much time he had lost. When his sporting director answered "Fourteen seconds", Anquetil replied: "Well, that's thirteen more than I need." Anquetil then went on to win the final time trial into Paris, extending his eventual winning margin to 55 seconds over Poulidor. It was Anquetil's fifth Tour victory, and the fierce duel between him and Poulidor started a cycling boom in France. Anquetil became the first rider since Coppi to win both the Giro and the Tour in the same year.

Anquetil raced little after the Tour, finishing seventh at the World Championships in Sallanches and skipping all of the end-of-season time trials.

2.6. Later Career and other Grand Tour wins

Anquetil's later career saw him continue to achieve significant victories, even as he explored new challenges and faced evolving dynamics in the sport.

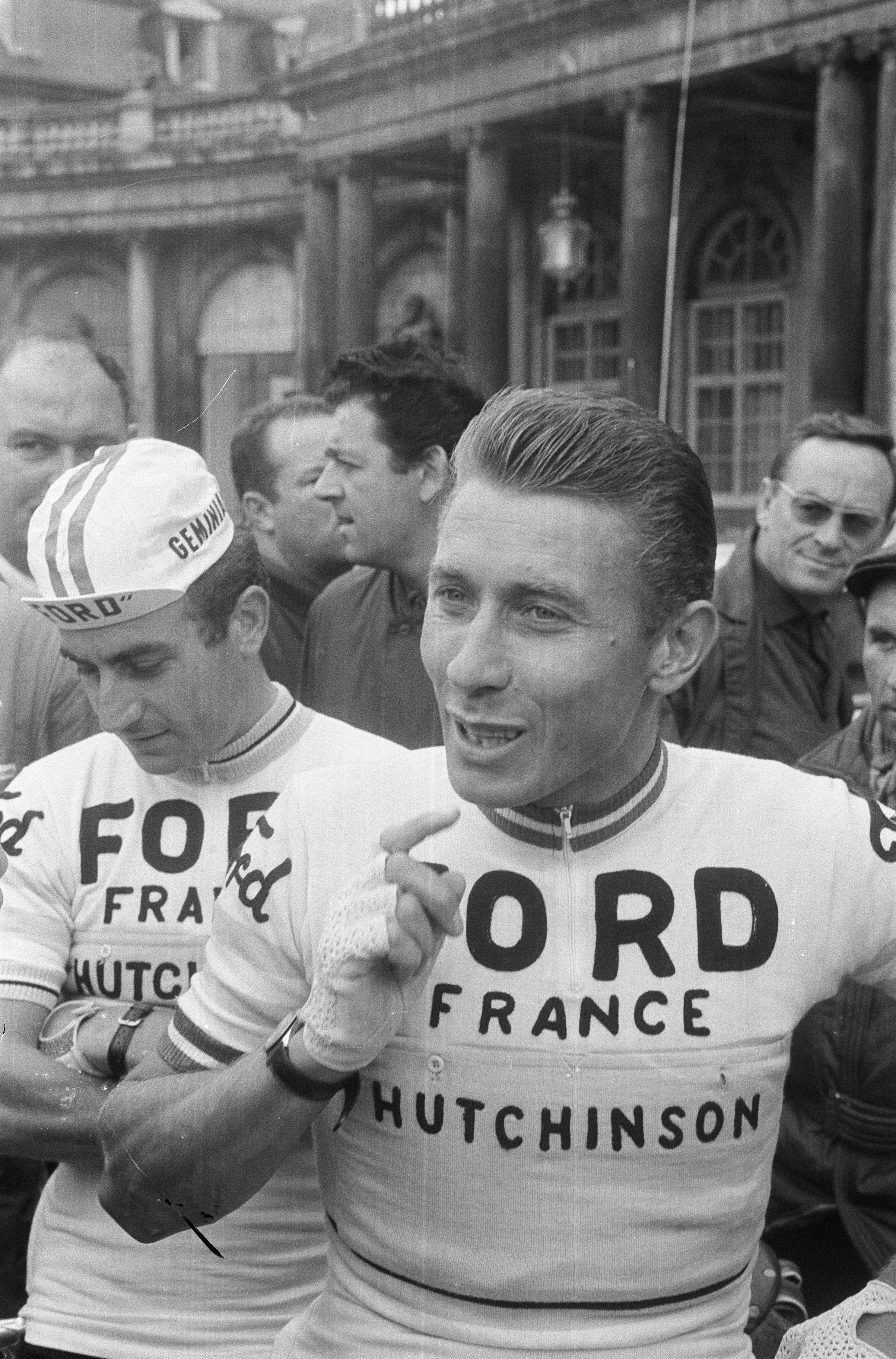

2.6.1. 1965: Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré and Bordeaux-Paris

For 1965, Saint-Raphaël ceased sponsoring Anquetil's team, which was then taken over by Ford France. In those days, the primary income for professional cyclists came from criteriums, small races held over laps in city centers, usually shortly after the Tour de France. Anquetil had realized that winning more Tours would not significantly increase his value in terms of start money, so he chose not to race any of the three Grand Tours in 1965. Early in the season, he won both Paris-Nice and the Critérium National and also participated for three days in the Monte Carlo Rally to appease his new sponsor, Ford.

Instead of the Grand Tours, Géminiani proposed another feat: the 1965 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré ended on the same day that the 348 mile (560 km) classic Bordeaux-Paris began, a race partly conducted behind dernys due to its excessive length. Géminiani pitched the idea to Anquetil's wife, Jeanine, who then convinced her husband to attempt to win both races. The announcement of this audacious attempt made headlines, bringing significant publicity to both events. The organizers of the Critérium du Dauphiné, initially reluctant, eventually aided the attempt by moving the start time of the final stage one hour forward to give Anquetil enough time to travel from Avignon (the Dauphiné's finishing town) to Bordeaux. At the Critérium du Dauphiné, Anquetil won narrowly, primarily through time bonuses at stage finishes and a slender victory in the time trial. He ultimately won the race by 1:43 minutes over Poulidor. Just 15 minutes after standing on the podium at 5 pm, Anquetil was in a car, being driven to a hotel for a bath and dinner, before heading to Nîmes airport to board a private jet that flew him to Bordeaux. The race to Paris started in the middle of the night, and Anquetil, having not slept, suffered at the beginning. Coming close to retiring in the early hours of the morning, he was convinced by his teammates to continue. He eventually joined a breakaway with Tom Simpson and Stablinski, then attacked on the Côte de Picardie climb, 5.0 mile (8 km) from the finish, and went on to win the race by 57 seconds ahead of Stablinski.

After failing to finish the World Championships in San Sebastián, Anquetil returned to the end-of-season time trials. He won the Grand Prix des Nations ahead of Altig and then beat Gianni Motta at the Gran Premio di Lugano. Anquetil then won his second Trofeo Baracchi, partnered with Stablinski. For the third time, Anquetil won the Super Prestige Pernod.

2.6.2. 1966: Grand Tour Return and Liège-Bastogne-Liège Victory

Anquetil started 1966 strongly with a victory at the Giro di Sardegna. At Paris-Nice, he was in the race lead but lost time to Poulidor on a hilly time trial because his bike was not fitted properly. Anquetil then formed an alliance with the Italian riders, including Gianni Motta, and their joint attacks pressured Poulidor, allowing Anquetil to win the stage and the overall race. In early May, he was on the start line for Liège-Bastogne-Liège, the oldest race on the cycling calendar and one of the sport's so-called monuments. Anquetil felt he had a chance of victory and escaped alone from a group containing Motta, Felice Gimondi, and a young Eddy Merckx. Although the trio worked well together to chase him, Anquetil's advantage continued to grow until the finish, where he won by almost five minutes. After the finish, while conducting interviews, he was approached and told he needed to provide a urine sample for doping control, but he ignored it and left. The next day, news broke that he had been disqualified by the Belgian cycling federation for his refusal. Following Anquetil's insistence that he had not been officially approached for the test, the authorities relented, and his victory was allowed to stand.

Unlike the previous year, Anquetil lined up for the 1966 Giro d'Italia. On the very first stage, he suffered two flat tires when an overenthusiastic fan tried to give him water, fell, and the glass bottle broke on the ground. A 22-rider group, containing all the other favorites, got away while Anquetil's tires were being attended to, and at the finish, he had lost 3:15 minutes. A second-place finish behind Vittorio Adorni in the stage 13 time trial brought him up to tenth place overall, but Anquetil no longer felt he could win the Giro and focused on preventing Gimondi from winning, as he considered the rising popularity of the young Italian a threat to his financial opportunities during the criteriums. After some strong riding in the mountain stages, Anquetil eventually finished third in the Giro, 4:40 minutes behind winner Motta.

The 1966 Tour de France was again expected to be a battle between Anquetil and Poulidor. On stage 9, Anquetil led a strike by the riders against the newly established anti-doping controls. Both Anquetil and Poulidor mainly marked each other, allowing Anquetil's teammate Lucien Aimar and Jan Janssen to gain time on stage 10. Poulidor won the time trial on stage 14b, seven seconds ahead of Anquetil. On stage 17, Aimar took advantage of the stalemate to break away from the lead group, win the stage, and take over the race lead. Anquetil, weakened by illness, helped Aimar by chasing down attacks from Janssen and Poulidor over the next stage before dropping out the following day. Aimar eventually won the Tour ahead of Janssen and Poulidor.

After the Tour, Anquetil competed at the World Championships held on the Nürburgring racing circuit. Late in the race, Anquetil and Poulidor were in a leading group with Motta, but both Frenchmen did not work together, allowing Altig to catch back up. In the final sprint to the line, Altig, by far the best sprinter, easily won, taking the title on home soil. Anquetil finished second, ahead of Poulidor, the highest position he would ever achieve in the World Championships. Anquetil then started and won the Grand Prix des Nations for the ninth time in his career, the final time he would ride the race. In the Super Prestige Pernod, Anquetil was highly placed going into the final race of the competition, the Giro di Lombardia. He finished fourth, earning him enough points to win the season-long competition for the fourth and last time in his career.

2.6.3. 1967-1969: Final Years and Invalidated Hour Record Attempt

With Ford France pulling out of sponsorship, Anquetil, like many of his teammates and director Géminiani, switched over to the Bic team. By 1967, Anquetil started to appear in fewer one-day races but lined up on short notice at the Critérium National, held in his hometown of Rouen, and won. Anquetil then again started at the Giro d'Italia, losing some time early on, before moving into the pink jersey with a fourth place in the stage 16 time trial, as all other favorites put in poor rides. He lost the lead the next day to Silvano Schiavon, who had shared a successful breakaway with Franco Balmamion. Having lost all but two teammates by the start of stage 20, Anquetil managed to limit his losses on the stage to regain the overall lead, albeit just 34 seconds ahead of Gimondi. During the following stage, he fended off several attacks, but eventually Gimondi managed to escape, gaining 4:09 minutes on Anquetil, relegating him to second place. On the penultimate stage on the final day, Anquetil made several attacks but was unable to break away from Gimondi. Thus tired, he proceeded to lose second place to Balmamion and finished the Giro in third. In 2012, it was revealed that former deputy race director Giovanni Michelotti admitted late in his life to having aided Gimondi on stage 21 by giving him the slipstream of the race organization's car as he was riding away from Anquetil. He allegedly did so to make up for the fact that he had annulled the result of stage 19 to Tre Cime di Lavaredo after many riders had been pushed up the climb by spectators. Gimondi had originally won that stage and gained the pink jersey before the result was taken back.

For its 1967 edition, the Tour de France reverted to national teams, and Marcel Bidot picked Poulidor as leader, while Anquetil stayed away. He instead decided that he would make an attempt at breaking Rivière's now eleven-year-old hour record. On 27 September, he made the attempt, again at the Velodromo Vigorelli, beating the record by 479 ft (146 m). After Anquetil finished his ride, he was approached by the doctor appointed by the sport's governing body, the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), to conduct his doping test. Géminiani protested that there was no lavatory on site at the velodrome and that Anquetil would not provide the urine sample out in the open. Since the doctor refused to travel with Anquetil to his hotel, no test was done, and Anquetil's record was therefore never ratified by the UCI. For the first time in his career, Anquetil was not chosen as part of the French team at the World Championships, but Anquetil managed a second place at the Trofeo Baracchi, partnering Bernard Guyot, to end his season. At the end of the year, Anquetil became chairman of the French Professional Cyclists Union, responsible for advocating the riders' interests towards the governing bodies and race organizers.

The final two seasons of Anquetil's career were relatively quiet. He did not race much in 1968, with his only victory coming at the Trofeo Baracchi, riding together with Gimondi. In 1969, he finished third at Paris-Nice and then won the Tour of the Basque Country, his last victory as a professional. His last professional race on the road was the World Championship road race in Zolder, where he placed 40th. He participated in a number of autumn criteriums and raced for the last time in Paris at the La Cipale velodrome at a track event; the venue would later be named after him. Anquetil's final outing was at a track event in Belgium on 27 December 1969.

2.7. Riding Style

Anquetil was known for his distinctive and elegant cycling technique, characterized by smooth pedaling, tactical brilliance, and exceptional performance in time trials. His riding style earned him the nickname "Maître Jacques."

According to American journalist Owen Mulholland, "The sight of Jacques Anquetil on a bicycle gives credence to an idea we Americans find unpalatable, that of a natural aristocracy. From the first day he seriously straddled a top tube, 'Anq' had a sense or perfection most riders spend a lifetime searching for. Between 1950, when he rode his first race, and nineteen years later, when he retired, Anquetil had countless frames underneath him, yet that indefinable poise was always there."

Mulholland further described his appearance: "The look was that of a greyhound. His arms and legs were extended more than was customary in his era of pounded post World War II roads. And the toes pointed down. Just a few years before, riders had prided their ankling motion, but Jacques was the first of the big gear school. His smooth power dictated his entire approach to the sport. Hands resting serenely on his thin Mafac brake levers, the sensation from Quincampoix, Normandy, appeared to cruise while others wriggled in desperate attempts to keep up." His ability to ride alone against the clock in individual time trial stages was exceptional, earning him the name "Monsieur Chrono."

3. Post-retirement Activities

After retiring from professional cycling, Anquetil dedicated his time to various endeavors, including managing his farm, engaging in business ventures, and remaining deeply involved in the cycling world through media and administrative roles.

Anquetil spent most of his post-retirement life tending to his own farm, though it was not profitable. He also owned several properties in Cannes and a gravel pit in Normandy. Beyond these business pursuits, Anquetil served as race director for both Paris-Nice and the Grand Prix du Midi Libre. He wrote columns for the L'Equipe sports newspaper and worked as a commentator during races, initially for Europe 1 radio and later for Antenne 2 television. In the early 1970s, Anquetil agreed to assist Richard Marillier, who had been his superior in the army in Algeria, in running the French national cycling team. While Anquetil did not fulfill many practical functions in this position, his presence helped lend a greater sense of authority to Marillier, who was relatively unknown in the cycling world. Anquetil continued in this role until the 1987 UCI Road World Championships, shortly before his death.

4. Rivalry and Social Significance

The intense and iconic rivalry between Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor transcended the sport, becoming a significant cultural phenomenon in France.

Despite Anquetil consistently beating Poulidor in the Tour de France, Poulidor remained more popular with the French public. The divisions between their fans became stark, emblematic of a split between "old France" and "new France," as noted by sociologists studying the Tour's impact on French society. The depth of these divisions is illustrated by a story, possibly apocryphal, told by Pierre Chany, who was close to Anquetil: "The Tour de France has the major fault of dividing the country, right down to the smallest hamlet, even families, into two rival camps. I know a man who grabbed his wife and held her on the grill of a heated stove, seated and with her skirts held up, for favouring Jacques Anquetil when he preferred Raymond Poulidor. The following year, the woman became a Poulidor-iste. But it was too late. The husband had switched his allegiance to Gimondi. The last I heard they were digging in their heels and the neighbours were complaining."

Jean-Luc Boeuf and Yves Léonard, in their study, wrote that those who identified with Jacques Anquetil admired his priority of style and elegance in his riding. Behind his fluidity and apparent ease was the image of a winning France, and those who took risks identified with him. Conversely, humble people saw themselves in Raymond Poulidor, whose face, lined with effort, represented the life they led working tirelessly. His common-sense declarations resonated with crowds, such as his remark that "a race, even a difficult one, lasts less time than a day bringing in the harvest." A large segment of the public thus identified with the one who symbolized bad luck and the eternal position of runner-up, an image that was far from true for Poulidor, whose record was particularly rich, including victories in races like Milan-San Remo, La Flèche Wallonne, the Vuelta a España, and Paris-Nice. Even today, the expression "eternal second" and the "Poulidor Complex" are associated with a hard life, as an article by Jacques Marseille in Le Figaro highlighted with the headline "This country is suffering from a Poulidor Complex."

5. Personal Life and Family Relations

Jacques Anquetil's personal life was notably complex, marked by unconventional relationships and family dynamics that extended beyond traditional norms.

In March 1957, Anquetil began an affair with Jeanine Boëda, the wife of his doctor and seven years his senior. They had known each other for several years prior to their relationship. Anquetil had just been discharged from the army, where, in Algeria, he had also begun an affair with Paule Voland, a ballet dancer at the Opera d'Algers. This affair caused a public sensation, and Voland traveled to Rouen in June 1957 to visit Anquetil's parents, believing he would propose marriage to her. He eventually had Jeanine deliver the news to Voland that he did not intend to do so.

In early 1958, Jeanine confessed the ongoing affair to her husband, who initially denied her a divorce. Anquetil then abandoned a training camp in the Mediterranean to travel to Normandy and appeared at the Boëdas' doorstep. Jeanine, dressed only in her night clothes, left with him for Paris. They lived together from that point on. Jeanine's two children, her daughter Annie and her son Alain, moved in with them two years later. Jeanine would accompany Anquetil to most of his races, which was unusual for a partner at the time. By the end of 1958, her husband granted Jeanine a divorce, and she and Anquetil were married on 22 December 1958. In late 1967, Anquetil purchased a château next to the farm he owned near Rouen. He prolonged his career by two years to be able to pay for it.

Following his retirement from professional cycling, Anquetil had a strong desire to father a child of his own; however, Jeanine was no longer able to conceive. Anquetil therefore suggested using a surrogate mother, someone they would pay to have their child. Jeanine, disliking the idea of a stranger whom they might deprive of their child, instead approached her 18-year-old daughter Annie, who consented to the idea of having a child with her stepfather. Even after their daughter, Sophie, was born in 1971, Annie and Anquetil remained in a sexual relationship while he remained happily married to Jeanine for another 12 years. While the general public was unaware of the situation surrounding Sophie's parentage, according to Jeanine, their close friends knew about it. Annie eventually met another man and ended her relationship with Anquetil, moving out in 1983, while Sophie initially remained with him and her grandmother. Several months later, in an apparent attempt to win back Annie by making her jealous, Anquetil seduced Dominique, wife of his stepson Alain, who both lived with the family. Anquetil's new affair broke the family apart, with Sophie moving in with Annie and Jeanine leaving to live in Paris shortly thereafter. Alain also left and remarried. Anquetil and Jeanine were eventually divorced in September 1987. Dominique and Anquetil had a son together, Christopher, born on 2 April 1986.

6. Doping and Controversies

Jacques Anquetil's career was marked by his open and unapologetic stance on doping, which generated significant controversy and sparked debates about ethics in professional cycling.

Anquetil never hid that he took drugs. In a debate with a government minister on French television, he famously stated that only a fool would imagine it was possible to ride Bordeaux-Paris on just water. He argued that he and other cyclists had to ride through "the cold, through heat waves, in the rain and in the mountains," and therefore had the right to treat themselves as they wished, adding: "Leave me in peace; everybody takes dope." There was implied acceptance of doping even at the highest levels of the state; Charles de Gaulle reportedly said: "Doping? What doping? Did he or did he not make them play the Marseillaise [the national anthem] abroad?"

Pierre Chany commented on Anquetil's candor: "Jacques had the strength - for which he was always criticised - to say out loud what others would only whisper. So, when I asked him 'What have you taken?' he didn't drop his eyes before replying. He had the strength of conviction." Anquetil argued that professional riders were workers and had the same right to treat their pains as, for example, a geography teacher. However, this argument found less support as more riders were reported to have died or suffered health problems due to drug-related incidents, including the death of Tom Simpson in the 1967 Tour de France.

Despite his open admission, there was significant support within the cycling community for Anquetil's argument that if rules and tests were to be implemented, they should be carried out consistently and with dignity. He asserted that it was professional dignity, the right of a champion not to be ridiculed in front of his public, that led to his refusal to take a test in the center of the Vigorelli track after breaking the world hour record in 1967. The Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) did not ratify the record due to his refusal. Anquetil was hurt that the French government had never sent him a telegram of congratulations for his record but sent one to the Belgian rider Ferdinand Bracke when he subsequently broke Anquetil's unratified time. This demonstrated the unacceptability of Anquetil's arguments to official bodies, and he was quietly dropped from future French teams.

7. Illness and Death

Jacques Anquetil's life came to an end in 1987 after a battle with cancer, marking the passing of a legendary figure in cycling.

Anquetil was diagnosed with an advanced form of stomach cancer on 25 May 1987. According to both his childhood friend Dieulois and fellow Tour winner Bernard Hinault, Anquetil delayed seeking proper medical treatment, prioritizing his commentating duties over the summer before finally going to the hospital. On 11 August, he underwent a surgical removal of his stomach. He died on 18 November 1987, at the Saint Hilaire Clinic in Rouen, surrounded by his daughter Sophie and Dominique, the mother of his youngest son.

8. Legacy and Evaluation

Jacques Anquetil's lasting impact on professional cycling is profound, solidifying his status as a pioneering figure whose strategic approach and numerous victories reshaped the sport.

Anquetil is celebrated as the first cyclist to win the Tour de France five times, a feat that cemented his legend. He was also the first rider to achieve overall victories in all three Grand Tours: the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia, and Vuelta a España. His exceptional ability in individual time trials, which earned him the nickname "Monsieur Chrono," revolutionized Grand Tour strategy, demonstrating that a rider could win major races by minimizing losses in the mountains and dominating against the clock. His elegant and smooth riding style, described as that of a "beautiful pedaling machine," further contributed to his iconic image, earning him another moniker, "Maître Jacques."

Posthumously, Anquetil has received numerous tributes. The 1997 Tour de France paid homage to him on the 40th anniversary of his first Tour victory and ten years after his death, by having the Grand Départ around Rouen, his hometown. A ceremony was held at his grave, and a pier in Quincampoix was renamed Quai Anquetil. His intense rivalry with Raymond Poulidor captivated the French public and became a cultural touchstone, symbolizing contrasting aspects of French society. Despite the controversies surrounding his open stance on doping, Anquetil's achievements and his candid honesty about the realities of professional cycling left an indelible mark on the sport's history.

9. Major Achievements and Awards

Jacques Anquetil's career was distinguished by an impressive array of victories across Grand Tours, major stage races, and one-day classics, alongside significant world records and prestigious awards.

Grand Tour General Classification Wins:

- Tour de France: 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964 (5 overall wins)

- Giro d'Italia: 1960, 1964 (2 overall wins)

- Vuelta a España: 1963 (1 overall win)

Other Major Wins:

- Grand Prix des Nations: 9 times (1953, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1961, 1965, 1966)

- Paris-Nice: 5 times (1957, 1961, 1963, 1965, 1966)

- Critérium National de la Route: 4 times (1961, 1963, 1965, 1967)

- Super Prestige Pernod International: 4 times (1961, 1963, 1965, 1966)

- Critérium des As: 3 times (1959, 1960, 1965)

- Gran Premio di Lugano: 3 times (1953, 1958, 1960, 1961, 1965)

- Trofeo Baracchi: 2 times (1962 with Rudi Altig, 1965 with Jean Stablinski, 1968 with Felice Gimondi)

- Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré: 1963, 1965 (2 overall wins)

- Four Days of Dunkirk: 1958, 1959 (2 overall wins)

- Giro di Sardegna: 1966 (1 overall win)

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège: 1966 (1 win)

- Gent-Wevelgem: 1964 (1 win)

- Bordeaux-Paris: 1965 (1 win)

- Volta a Catalunya: 1967 (1 overall win)

- Tour of the Basque Country: 1969 (1 overall win)

- Six Days of Paris: 1957 (with André Darrigade and Ferdinando Terruzzi)

World Records:

- Hour record: 29 mile (46.159 km) (29 June 1956, Velodromo Vigorelli, Milan)

- Anquetil also set a distance of 30 mile (47.493 km) on 27 September 1967 at the Velodromo Vigorelli, but this record was never ratified by the UCI following his refusal to take a post-race doping control.

Awards and Decorations:

- BBC Overseas Sports Personality of the Year: 1963

- Knight of the Legion of Honour (France): 1966

Championship Results:

- Olympic Games: Bronze medal in the Team road race (1952 Helsinki)

- UCI Road World Championships: Silver medal in the Road race (1966 Nürburgring)

- UCI Track Cycling World Championships: Silver medal in the Individual pursuit (1956 Copenhagen)

9.1. General Classification Results Timeline

Grand Tour general classification results Grand Tour 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 Vuelta a España Not held - - - - - - - DNF 1 - - - - - - Giro d'Italia - - - - - - 2 1 2 - - 1 - 3 3 - - Tour de France - - - - 1 DNF 3 - 1 1 1 1 - DNF - - - 9.2. Major Stage Race General Classification Results

Major stage race general classification results Race 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 Paris-Nice - 7 - - 1 10 11 DNF 1 DNF 1 6 1 1 16 10 3 Tirreno-Adriatico Not held - - - - Tour of the Basque Country Not held 1 Tour de Romandie - - - - - - - 8 10 - - - - - - - - Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré - - 15 - - - - - - 12 1 - 1 - Not held 4 Volta a Catalunya - - - - - - - - - - - - - 2 1 - - Tour de Suisse - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9.3. Classics Results Timeline

Monuments results timeline Monument 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 Milan-San Remo - - - 12 17 10 - 23 - - - - - - - - - Tour of Flanders - - - - - - - 14 - - - - - - - - - Paris-Roubaix - 53 15 31 25 14 24 8 60 31 - - 16 - - - - Liège-Bastogne-Liège - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 - 4 - Giro di Lombardia - - - - 23 12 21 34 17 - - - 8 4 - - - 9.4. Major Championship Results Timeline

1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 World Championships - 5 6 - 6 DNF 9 9 13 15 14 7 DNF 2 - 11 40 National Championships - - - DNF - - - - - - 3 - 3 - - - - Legend - Did not compete DNF Did not finish