1. Overview

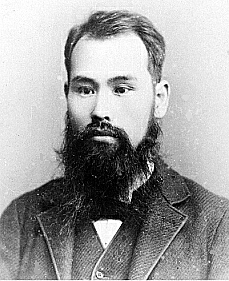

Iwamoto Yoshiharu, also known as Iwamoto Zenji, was a prominent Japanese educator, journalist, and social reformer during the Meiji era. Born on July 30, 1863, he became an early and influential advocate for women's education and expanded civil rights for women in Japan. He is best known for founding and editing influential magazines such as Jogaku Zasshi and for his significant role in the establishment and administration of Meiji Girls' School. His career was marked by a strong commitment to Christian principles and Western liberal thought, which he applied to his reform efforts, advocating for marriages based on love and respect. However, his legacy is complex and controversial; he faced accusations of womanizing and fraudulent activities, which severely impacted his reputation and contributed to the eventual closure of Meiji Girls' School. Despite these criticisms, his extensive literary output and pioneering work laid important groundwork for the advancement of women's roles in modern Japanese society.

2. Early Life and Education

2.1. Background and Family

Iwamoto Yoshiharu was born on July 30, 1863 (Bunkyū 3, 6th month, 15th day, in the old lunar calendar), in Izushi, Izushi Domain, which is now part of Toyooka City, Hyōgo Prefecture. He was the second son of 井上藤兵衛Inoue TōbeiJapanese, a Confucian scholar. In 1868 (Keiō 4), at the age of six, he was adopted into his maternal line by his uncle, 巌本範治Iwamoto HanjiJapanese, who was a chief retainer of the Fukumoto Domain.

2.2. Education and Intellectual Influences

In 1876 (Meiji 9), Iwamoto moved to Tokyo and began his formal education at Nakamura Masanao's Dōjinsha school. There, he engaged in intensive studies of English, Chinese classics, and liberalism. During this period, he was significantly influenced by the ideas of Western thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer.

In 1880 (Meiji 13), he advanced his studies at Tsuda Sen's Gakunōsha Nōgakkō, an agricultural school, where he focused on agriculture. From the following year, he began contributing short essays to the school's publication, 農業雑誌Nōgyō ZasshiJapanese (Agricultural Magazine). He was also a devoted reader of Ninomiya Sontoku's Hotokuki. In 1884 (Meiji 17), he was baptized by the pastor Kimura Kumaji at Shitaya Church, which is now known as the Japan Evangelical Lutheran Church Toshimaoka Church. After completing his studies at Gakunōsha, he became involved in editing 農業雑誌Nōgyō ZasshiJapanese and contributed articles to 基督教新聞Kiristokyō ShinbunJapanese (Christian Newspaper).

3. Career and Advocacy

Iwamoto Yoshiharu dedicated a significant portion of his career to promoting social reform and women's rights through education and publishing.

3.1. Advocacy for Women's Education and Social Reform

Iwamoto was a forceful advocate for fundamental changes in Japanese society concerning women's roles. He passionately called for improved education for women, the expansion of their civil rights, and the establishment of marriage on the basis of mutual love and respect between husband and wife. However, his progressive views were tempered by traditional expectations regarding women's domestic roles. He maintained that women's primary place was in the home, and their education should prepare them to manage efficient, hygienic, and economical households, thereby enabling them to raise intelligent, moral, and service-minded children. He was also a committee member of the Tokyo Prostitution Abolition Society, established in 1890, and campaigned against prostitution in various regions.

3.2. Publishing and Journalism

In 1884, Iwamoto collaborated with Kondō Kenzō to launch the magazine 女学新誌Jogaku ShinshiJapanese (New Magazine for Women's Studies). The term "Jogaku" itself was defined by Iwamoto as "studies for improving women's status, rights, and happiness." Although this initial venture lasted only one year, it laid the groundwork for their more enduring publication.

In 1885, Iwamoto and Kondō founded Jogaku Zasshi (女学雑誌Jogaku ZasshiJapanese, Women's Studies Magazine), which became a highly influential publication. Iwamoto wrote extensively for the magazine under various pen names, including Gessha Shujin, Gessha Shinobu, Zekū-shi, Midori, Momiji, and Kasumi. In the same year, he became the chief editor of 基督教新聞Kiristokyō ShinbunJapanese. Following Kondō Kenzō's sudden death in May 1886, Iwamoto took over as the editor of Jogaku Zasshi. In June 1887, he also became the nominal editor of 東京婦人矯風雑誌Tōkyō Fujin Kyōfū ZasshiJapanese (Tokyo Women's Temperance Magazine), published by the Tokyo Christian Women's Temperance Union. In 1890, he co-founded 女学生JogakuseiJapanese (Girl Student) with Hoshino Tenchi, a magazine that featured contributions from students of 18 Christian girls' schools. He eventually stepped down as editor of Jogaku Zasshi at the end of 1903.

3.3. Role in Meiji Girls' School

Beginning in 1885, Iwamoto played a pivotal role in the establishment and operation of Meiji Girls' School (明治女学校Meiji JogakkōJapanese) in Kōjimachi, Tokyo. He was among the key founders, alongside figures such as Tsuda Umeko, Kimura Kenzō, Shimada Saburō, and Tada Umachi, and also served as a teacher. After the sudden death of Kimura Abiko, Kimura Kenzō's wife and a director of the school, in August 1886, Iwamoto became the head teacher (教頭kyōtōJapanese) in March 1887, taking on significant administrative responsibilities. In 1892, he was appointed principal of the school.

The school faced financial difficulties due to a lack of economic aid from churches and missionaries. In February 1896, a devastating fire destroyed most of the school buildings, including the main schoolhouse, dormitory, and teachers' residences. This tragedy was followed shortly by the death of his wife, Wakamatsu Shizuko, who had been suffering from lung disease. Iwamoto worked to rebuild the school, but in the spring of 1904, he retired from his position as the school owner (校主kōshuJapanese). The school eventually closed in 1909, with some critics attributing its downfall to controversies surrounding Iwamoto's personal life.

3.4. Literary and Intellectual Debates

Iwamoto was an active participant in the intellectual discourse of the Meiji era. On April 11, 1889, he published an essay titled "Literature and Nature" in Jogaku Zasshi, influenced by Ralph Waldo Emerson. In this essay, he argued that "the best literature reflects nature as it is." This view sparked a notable debate with Mori Ōgai, a prominent literary figure, who countered in the May 11 issue of 国民之友Kokumin no TomoJapanese that beauty in literature emerges only through "idea." Iwamoto responded by asserting that human nature naturally follows nature, but Mori continued his rebuttal. The debate persisted until Iwamoto's final response on June 11.

His influence also extended to the literary Romanticists associated with Meiji Girls' School and Jogaku Zasshi, including Hoshino Tenchi, Kitamura Tōkoku, Shimazaki Tōson, and Hirata Tokuboku. However, these writers eventually found it difficult to continue working under Iwamoto's direction and, in 1893, went on to found their own influential literary magazine, 文学界BungakukaiJapanese.

3.5. Business Ventures and Overseas Activities

Beyond education and journalism, Iwamoto engaged in various business and overseas activities. In 1905, as a member of the 大日本海外教育会Dainippon Kaigai KyōikukaiJapanese (Great Japan Overseas Education Association), he traveled to Korea with Oshikawa Masayoshi. He became involved with the 皇国移民会社Kōkoku Imin GaishaJapanese (Kōkoku Immigration Company), which handled Japanese immigrants to Brazil. By 1907, he was a central figure in the 明治殖民会社Meiji Shokumin GaishaJapanese (Meiji Colonization Company), which managed immigration to Peru. He traveled to Peru the following year. However, the Meiji Colonization Company became embroiled in controversy, facing accusations of illegal distribution and issues with delayed or undelivered remittances for immigrants in 1908 and 1909, leading to its suspension and eventual dissolution.

In 1912, Iwamoto was involved in the founding of Cafe Paulista, a coffee direct import company established by Mizuno Ryū of the Kōkoku Immigration Company, and served as a director. In 1916, he established a trust partnership company on the former site of Meiji Girls' School. Later, in 1924, he became a director of Nikkatsu, a major Japanese film studio.

4. Personal Life and Family

In 1889 (Meiji 22), Iwamoto Yoshiharu married Wakamatsu Shizuko (若松賤子Wakamatsu ShizukoJapanese), an assistant teacher at Ferris Girls' School, at the Yokohama Kaigan Church. However, Shizuko died prematurely shortly after the devastating fire at Meiji Girls' School in 1896. Following her death, her younger sister, Miya, took on the responsibility of raising Iwamoto's children.

Iwamoto and Shizuko had three children: a daughter, Kiyoko (清子KiyokoJapanese), a son, Masahito (荘民MasahitoJapanese), and another daughter, Tamiko (民子TamikoJapanese). Their son, Masahito, later studied in the United States and worked at the U.S. Embassy in Japan. Masahito and his American wife, Marguerite Iwamoto (who became an English lecturer at Tokyo Woman's Christian University after coming to Japan), had a daughter named Iwamoto Mari, who became a renowned violinist. Iwamoto's daughters also married into notable families: Kiyoko's husband was Nakano Tomio, a legal scholar, and Tamiko's husband was Matsuura Kaichi, a scholar of English literature.

His younger brother, Iwamoto Sōji (巌本捷治Iwamoto SōjiJapanese, 1885-1954), was a graduate of the Tokyo School of Music. Sōji worked as a staff member at Meiji Girls' School and, in 1901, became the chief editor of 音楽之友Ongaku no TomoJapanese (Music Friend), a prominent music magazine. He later served as an auditor for Matsumoto Musical Instrument Manufacturing Company.

5. Controversies and Criticisms

Despite his public image as a Protestant reformer and women's enlightener, Iwamoto Yoshiharu was plagued by persistent and damaging rumors, particularly concerning his personal conduct and financial dealings.

He was widely accused of womanizing, with reports indicating that his wife, Wakamatsu Shizuko, had spoken about his infidelity. These accusations were further corroborated by former students of Meiji Girls' School. Sōma Kokkō, a student at the time, explicitly criticized Iwamoto for preying on his female students and even named victims who were allegedly driven to suicide as a result of his actions. Another graduate, Nogami Yaeko, later reflected on Iwamoto's downfall as one of the three most significant and formative events in her life.

Beyond personal misconduct, Iwamoto was also accused of fraudulent activities by contemporaries such as Hoshino Tenchi and Hirata Tokuboku. Following his loss of public standing, he was pejoratively labeled as a "hypocritical saint" and a "hypocrite." While Iwamoto himself maintained silence in response to these widespread accusations, his controversial behavior became a subject of literary commentary. Shimazaki Tōson's short story 黄昏TasogareJapanese (Twilight) is believed to have been modeled after Iwamoto.

The controversies surrounding Iwamoto had severe consequences for his reputation and for Meiji Girls' School. Hani Motoko, a prominent educator and former admirer of Iwamoto, critically assessed his spiritual life, stating that he "was not serious about serving God." She directly attributed the closure of Meiji Girls' School in 1909 to Iwamoto's "women's issues," describing the school as having been "taken to the land of demons" due to his actions and holding him responsible for its demise.

6. Later Life and Death

6.1. Later Activities and Ideology

Even after retiring from his direct role at Meiji Girls' School, Iwamoto continued to engage in religious and political activities. In 1899, shortly after the death of Katsu Kaishū, a prominent statesman of the late Edo period and early Meiji era, Iwamoto compiled and published 海舟余話Kaishū YowaJapanese (Remaining Tales of Kaishū), which consisted of conversations he had serialized in Jogaku Zasshi. He later revised and re-published this work as Kaishū Zadan (海舟座談Kaishū ZadanJapanese, Kaishū's Discourses) in 1930, further expanding it in 1937. His close relationship with Katsu Kaishū, whom he frequently visited, began when he sought an introduction for Kimura Abiko Shōden in 1887.

In his later years, Iwamoto became involved in political circles, even intervening in the cabinet formation of Hayashi Senjūrō. He named his own residence "神政書院Shinsei ShoinJapanese" (Divine Government Academy) and actively promoted State Shinto. He notably wrote a preface for the book 大日本は神国なりDainippon wa Shinkoku nariJapanese (Great Japan is a Divine Nation), reflecting his embrace of nationalist and Shinto ideologies.

6.2. Death

Iwamoto Yoshiharu passed away on October 6, 1942 (Shōwa 17), at his home in Nishi-Sugamo, Toshima Ward, Tokyo. He is buried in Somei Cemetery.

7. Legacy and Evaluation

Iwamoto Yoshiharu's legacy is a complex tapestry woven with pioneering achievements and significant controversies. He stands as a foundational figure in the history of women's education in Meiji Japan, having strenuously advocated for expanded educational opportunities and civil rights for women. Through his influential magazines, particularly Jogaku Zasshi, he provided a crucial platform for intellectual discourse on women's roles, marriage reform, and social progress, reaching a wide audience and shaping public opinion. His involvement in the establishment and administration of Meiji Girls' School further solidified his commitment to practical educational reform.

However, his contributions are overshadowed by serious criticisms regarding his personal conduct and alleged financial improprieties. Accusations of womanizing and the impact of these actions on his students and the school's reputation, as detailed by contemporaries like Sōma Kokkō and Hani Motoko, present a stark contrast to his public image as a moral reformer. The eventual closure of Meiji Girls' School is often directly linked to the controversies surrounding him, highlighting the detrimental effects of his personal failures on his institutional endeavors.

Despite these significant criticisms, Iwamoto's early and persistent efforts to challenge traditional gender roles and promote a more enlightened view of women's capabilities undeniably contributed to the broader movement for women's empowerment in Japan. His extensive writings and journalistic ventures introduced Western liberal ideas and fostered a critical environment for social change. His work on compiling Kaishū Zadan also preserved important historical insights from Katsu Kaishū. Ultimately, Iwamoto Yoshiharu remains a pivotal, albeit deeply flawed, figure whose life reflects the tensions and transformations of Meiji Japan's modernization process.

8. Publications

Iwamoto Yoshiharu was a prolific writer, editor, and translator. His works spanned educational theory, social commentary, and literary criticism, reflecting his diverse intellectual interests and his commitment to women's education and social reform.

8.1. Books

- 吾党之女子教育Wagatō no Joshi KyōikuJapanese (Our Party's Women's Education), Meiji Girls' School, 1892.

- 教育学講義Kyōikugaku KōgiJapanese (Lectures on Pedagogy), Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1893.

- 偉人物IjinbutsuJapanese (Great Figures), Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1894.

- Takahashi Dengorō, Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1895.

- 女学雑誌集 巌本善治 篇Jogaku Zasshi-shū Iwamoto Yoshiharu-henJapanese (Jogaku Zasshi Collection: Iwamoto Yoshiharu Volume), in Meiji Bungaku Zenshū 32 (Complete Works of Meiji Literature Vol. 32), Chikuma Shobō, 1973. This collection includes various essays he published in Jogaku Zasshi, such as:

- "小説論Shōsetsu-ronJapanese" (Theory of Novels), Issues 82-84.

- "文人記者の伉儷Bunjin Kisha no KōreiJapanese" (Marriages of Literary Journalists), Issues 94-95.

- "理想之佳人Risō no KajinJapanese" (Ideal Beautiful Woman), Issues 104-108.

- "女学の解Jogaku no KaiJapanese" (Explanation of Women's Studies), Issue 111.

- "小説家の着眼Shōsetsuka no ChakuganJapanese" (Novelist's Point of View), Issue 154.

- "国民之友第四十八号 文学と自然Kokumin no Tomo Dai Yonjūhachi-gō Bungaku to ShizenJapanese" (Kokumin no Tomo No. 48: Literature and Nature), Issue 159.

- "此の大沙漠界に、一人の詩人あれよKono Daisabaku-kai ni, Hitori no Shijin AreyoJapanese" (In This Great Desert World, Let There Be One Poet), Issue 161.

- "風流を論ずFūryū o RonzuJapanese" (On Elegance), Issue 210.

- "婚姻論Kon'in-ronJapanese" (On Marriage), Issues 273, 275, 277.

- "非恋愛を非とすHi-Ren'ai o Hi to SuJapanese" (To Deny Non-Love), Issue 276 (a rebuttal to Tokutomi Sohō's "Hi-Ren'ai" in 国民之友Kokumin no TomoJapanese Issue 125).

- "演劇の改良Engeki no KairyōJapanese" (Improvement of Drama), in Kindai Bungaku Hyōron Taikei 9 (Compendium of Modern Literary Criticism Vol. 9), Kadokawa Shoten, 1972.

8.2. Edited Works

- 木村鐙子小伝Kimura Abiko ShōdenJapanese (A Short Biography of Kimura Abiko), Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1887. (Includes a letter from Toyama Masakazu).

- 偉人物IjinbutsuJapanese (Great Figures), Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1894.

- Takahashi Dengorō, Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1895.

- In memory of Mrs. Kashi Iwamoto, with a collection of her English writings, Z. Iwamoto, Tokyo, 1896. (Reprinted by Ōzora-sha, 1995, supervised by Yamazaki Tomoko).

- 海舟余波Kaishū YowaJapanese (Remaining Waves of Kaishū), Jogaku Zasshi-sha, 1899. (Dictated by Katsu Kaishū).

- Kaishū Zadan (海舟座談Kaishū ZadanJapanese, Kaishū's Discourses), Iwanami Shoten, 1930. (A revised edition of 海舟余波Kaishū YowaJapanese).

- Kaishū Zadan (増補ZōhoJapanese, Enlarged Edition), Iwanami Shoten, 1937. (An expanded edition of the 1930 version).

- Kaishū Zadan (新訂ShinteiJapanese, Newly Revised, annotated by Katsube Shincho), Iwanami Shoten, 1983. (A new revision of the 1937 edition).

- Kaishū Zadan (ワイド版Waido-banJapanese, Wide Edition), Iwanami Shoten, 1995. (A wide-format edition of the 1983 revision).

8.3. Supervised Works

- 廃物利用Haibutsu RiyōJapanese (Waste Utilization), by Takahashi Yōryō, Keizai Zasshi-sha, 1885 (Volume 1) and 1886 (Volume 2). (Also known as Keizai Hihō Haibutsu Riyō Sutaremono Yōikata).

- 廃物利用 経済秘法 すたれ物用ゐ方Haibutsu Riyō Keizai Hihō Sutaremono YōikataJapanese, by Kondō Kenzō, Keizai Zasshi-sha, 1887.

8.4. Translations

- 女の未来Onna no MiraiJapanese (Woman's Future), by Frances King Carey, Yoron-sha, 1887.

- "人肉質入裁判Ninjū Shitsuirei SaibanJapanese" (The Trial of Human Flesh Pawning), a translation of William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, published in Bungaku Sōshi, 1885. (Included in Meiji Hon'yaku Bungaku Zenshū Shinbun Zasshi-hen 1 (Shakespeare-shū 1), Ōzora-sha, 1996).

- "不思議の新衣裳Fushigi no Shin IshōJapanese" (The Emperor's New Clothes), a translation of Hans Christian Andersen's story, published in Jogaku Zasshi, 1888. (Included in Meiji Hon'yaku Bungaku Zenshū Shinbun Zasshi-hen 46 (Andersen-shū), Ōzora-sha, 1996).

- "三人の姫Sannin no HimeJapanese" (Three Princesses), a translation of a work by William Shakespeare, published in Jogaku Zasshi, 1887. (Included in Meiji Hon'yaku Bungaku Zenshū Shinbun Zasshi-hen 2 (Shakespeare-shū 2), Ōzora-sha, 1996).