1. Overview

Hani Motoko, born Matsuoka Motoko, 羽仁 もと子Hani MotokoJapanese, (1873-1957) is widely recognized as Japan's first female journalist, a pioneer who broke barriers in a male-dominated profession. Beyond her impactful journalism, she was a visionary educator and social reformer, co-founding the Jiyu Gakuen educational institution and the Fujin no Tomo publishing house. Her contributions extended to practical aspects of daily life, notably with the invention and popularization of the household ledger (kakeibo), a tool that empowered women in managing family finances and promoting economic independence. Throughout her life, Hani Motoko championed the enhancement of women's social roles and advocated for self-reliance and personal freedom, driven by her deep Christian faith and a commitment to social progress.

2. Early Life and Education

Hani Motoko's formative years were shaped by a blend of traditional upbringing and exposure to new educational opportunities, alongside the influence of her family and burgeoning Christian faith.

2.1. Birth and Family Background

Hani Motoko was born on September 8, 1873, in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture, as Matsuoka Motoko. She hailed from a family with a strong historical background, her grandfather, Matsuoka Tadataka, being a former samurai. Raised primarily by her grandfather and father, a lawyer, Hani developed a close bond with her father. In contrast, she perceived the other women in her household, including her grandmother and mother, as "naïve" due to their illiteracy, highlighting her early recognition of the limitations placed upon women. The divorce of her parents later caused her deep distress, leaving a lasting impact on her personal life. Her birth coincided with the establishment of Japan's modern public school system in 1872, a period when the Meiji government prioritized education to modernize the country. While the Meiji government promoted a male-centered society and the "good wife, wise mother" (ryōsai kenbo) ideal for women, the Taishō period (1912-1926) saw increased accessibility to women's education beyond elementary school, reflecting a global trend towards liberalism.

2.2. Schooling and Christian Baptism

Hani began her education at elementary school in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture. From an early age, she exhibited a competitive spirit, reportedly ranking herself among boys. In 1884, she received an award for academic excellence from the Ministry of Education. Benefitting from her grandfather's support, she was able to pursue higher education, transferring to the Tokyo Prefectural First Higher Women's School (Tōkyō Furitsu Daiichi Kōtō Jogakkō) in 1889. At this time, no colleges in Japan accepted women.

In 1890, while enrolled, she was baptized as a Christian, a faith she would uphold throughout her life, adopting a non-churchism stance that did not involve affiliation with a specific church. Although she failed the entrance examination for the Tokyo Women's Higher Normal School (Tōkyō Joshi Kōtō Shihan Gakkō) in 1890, her pursuit of knowledge continued. In 1891, she enrolled in the higher course of Meiji Women's School (Meiji Jogakkō), where Iwamoto Yoshiharu, the school's principal and editor of Jogaku Zasshi (a women's magazine), became her mentor. Her experience at Meiji Women's School, including assisting with proofreading for Jogaku Zasshi, provided her with foundational knowledge in magazine production. She withdrew from Meiji Women's School in 1892.

2.3. Early Career as a Teacher

Before embarking on her influential journalism career, Hani Motoko worked as a teacher. In 1892, she returned to her hometown region, securing positions as an elementary school teacher and at Morioka Jogakko (a girls' school) in Morioka. At the time, teaching was one of the most prestigious and lucrative careers available to women in Japan, with only a small percentage (5.9%) of teachers being female. This early professional experience provided her with insights into the importance of education and women's roles in society.

3. Journalism Career

Hani Motoko's pioneering efforts as Japan's first female journalist significantly shaped public discourse and paved the way for other women in the field.

3.1. Joining Hochi Shimbun and Pioneering Journalism

In 1897, Hani Motoko moved back to Tokyo and joined the Hochisha, which later became the Hochi Shimbun newspaper. She began her tenure as a copy editor, a role that allowed her to gain a deeper understanding of newspaper operations. Demonstrating her talent and initiative, she frequently submitted her own articles, earning recognition for her abilities. In April 1899, her talent was formally acknowledged when she was promoted to a reporting position, making her, at 24 years old, Japan's first officially recognized female journalist.

One of her early successes was a newspaper column titled "Fujin no sugao" (Portraits of Famous Women), which featured profiles of prominent married women in Japan. Hani took the initiative to cover this story, even though it was not formally assigned to her. Her interview with Lady Tani, the wife of Tani Kanjo, was an instant success, leading to widespread positive responses from readers and her subsequent promotion to reporter by Miki Zenpachi, the newspaper's president. As a reporter, Hani quickly gained a reputation for her ability to cover often-neglected social issues, including child care and orphanages, bringing crucial public attention to these areas. In her autobiography, she proudly referred to herself as "the first female newspaper reporter."

3.2. Emphasis on Women's Roles and Social Activism

In the 1920s, Hani Motoko actively engaged in discussions about women's roles, seeking to elevate their status in society. She navigated the complex debates between the ideas of absolute equality for women and the traditional view of female inferiority. Hani argued that women were equal to men, particularly within the domestic sphere, advocating for its significance and value. She played a key role in popularizing the virtues of the Western-style "housewife," not as a limiting role but as an empowered manager of the household.

She collaborated with bureaucrats to sponsor exhibitions focused on improving daily life and delivered lectures that emphasized Christian ideals, independence, self-esteem, and personal freedom. Hani Motoko was among several prominent female leaders of her time, including Ichikawa Fusae, Yoshioka Yayoi, and Shigeyo Takeuchi, who actively worked with the government to improve the lives of women in Japan. However, it is also notable that Hani, like many activists during a period of nationalistic fervor, utilized the escalating war with China in 1937 as an opportunity to elevate the position of Japanese women within the state, often referencing Western models. Her followers, notably led by her daughter Setsuko, actively assisted the wartime government in promoting economic austerity and rationalization of daily life among women.

4. Publishing and Educational Activities

Hani Motoko's impact extended significantly into the realms of publishing and education, where she established foundational institutions that continue to influence Japanese society.

4.1. Fujin no Tomo and the Popularization of Household Ledgers

After her second marriage, Hani Motoko and her husband, Hani Yoshikazu, left Hochi Shimbun. In 1903, driven by a vision to provide practical guidance for women, they founded a new women's magazine called 家庭之友 (Katei no Tomo, meaning "Home's Friend"). This publication marked a significant step in their joint mission to empower women through information.

A year later, in 1904, Hani Motoko made another groundbreaking contribution by inventing and publishing Japan's first modern household ledger (kakeibo). This simple yet revolutionary tool allowed women to track their family's income and expenses, fostering financial literacy and enabling more efficient household management. In 1908, the magazine was re-titled 婦人之友 (Fujin no Tomo, meaning "Women's Friend"), and the Fujin no Tomo Publishing house was formally established. This new name underscored their focus on women's empowerment beyond just the home. In 1914, they launched 子供之友 (Kodomo no Tomo, meaning "Children's Friend"), a sister magazine aimed at children. However, under the National General Mobilization Law during the wartime regime, most publications faced stringent control by the Japan Publishing Association, leading to the abolishment of Kodomo no Tomo, with only Fujin no Tomo allowed to continue. After the war, the title Kodomo no Tomo was later transferred to Fukuinkan Shoten, which continues to publish a children's magazine under that name.

4.2. Founding of Jiyu Gakuen

In 1921, recognizing the need for an education that nurtured independence and practical skills, Hani Motoko and Hani Yoshikazu co-founded Jiyu Gakuen (自由学園) in what was then old Mejiro, Tokyo (present-day Nishi-Ikebukuro). Initially established as a private school for girls, its primary aim was to provide a domestic education rooted in the values they promoted in their publications, particularly for the children of Fujin no Tomo readers.

The school's name, "Jiyu Gakuen" (Freedom School), was inspired by the New Testament verse, "The truth will set you free" (John 8:32), reflecting their philosophy of fostering genuine freedom through knowledge and self-reliance. A notable feature of Jiyu Gakuen's early days was the involvement of renowned American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who was visiting Japan at the time. Impressed by the Hani couple's vision for a family-centered school, Wright actively undertook the design of the school building, which is now preserved as the Jiyu Gakuen Myonichikan and designated an Important Cultural Property of Japan, open to the public. As the school expanded, it moved to Higashikurume, Tokyo, in 1925, with the funds for the new facilities largely generated by selling off surrounding land to related parties.

4.3. Establishment of the National Tomo no Kai

In 1930, a significant development occurred with the establishment of the National Tomo no Kai (全国友の会), a voluntary association composed of dedicated readers of Fujin no Tomo magazine. This organization served as a community for women who shared Hani Motoko's vision and applied her principles in their daily lives. The association fostered a network of support, practical learning, and social engagement among its members, further extending the reach and influence of Hani's philosophy beyond the pages of the magazine. This association continued to exist as of 1999, demonstrating its enduring legacy.

5. Philosophy and Beliefs

Hani Motoko's core philosophy was deeply intertwined with her Christian faith, profoundly influencing her views on women's roles and her approach to education.

5.1. Christian Faith and Non-Churchism

Hani Motoko's Christian faith, embraced in 1890 through baptism, was a lifelong guiding principle. Despite her strong belief, she adhered to a unique stance of non-churchism (Mukyōkai), meaning she did not formally belong to any specific Christian church or denomination. This approach allowed her to develop her spiritual life independently, emphasizing personal conviction and direct engagement with Christian ideals. Her faith instilled in her a strong sense of purpose, driving her commitment to social improvement and the empowerment of individuals. Many of her initiatives, including her work on women's roles and education, were imbued with Christian values of independence, self-esteem, and personal freedom.

5.2. Views on Women and Educational Philosophy

Hani Motoko's perspective on women, while rooted in the societal context of her time, advocated for the significant and equal role of women, particularly within the domestic sphere. She challenged the prevailing notion of female inferiority by emphasizing women's capacity for independence and the vital contribution they could make as managers of the household. While the Meiji government promoted the "good wife, wise mother" ideal, Hani pragmatically utilized and reshaped this concept, imbuing it with notions of modern efficiency, financial acumen, and personal development, thus redefining it beyond mere obedience and domesticity.

Her educational philosophy, most prominently realized in Jiyu Gakuen, focused on holistic development. It aimed to prepare women not just for marriage, but for leadership roles within their families and communities, promoting self-reliance and practical skills. The emphasis was on experiential learning, critical thinking, and the cultivation of a strong moral character. The school's name itself, "Freedom School," derived from a biblical verse, underscored her belief that true knowledge and self-awareness lead to personal liberation. This educational approach sought to empower women to lead meaningful and independent lives, contributing positively to society.

6. Personal Life

Hani Motoko's personal life, particularly her experiences with marriage, deeply influenced her views on women's independence and her dedication to public service.

6.1. Marriages and Family Life

Hani Motoko's first marriage occurred in 1892, but it was short-lived and ended in divorce. According to her autobiography, she married with the intention of reforming the man she loved from a lifestyle she considered "vulgar," hoping to change him. However, this endeavor proved unsuccessful, leading to the dissolution of the marriage. She kept the divorce a secret from her family, describing it as the second most painful emotional crisis of her life, surpassed only by the failure of her parents' marriage. Despite the personal anguish, she later reflected on this experience as a necessary liberation, stating, "I have always feared that this painful episode of my life, of which I am ashamed even today, might jeopardize the effectiveness of my public service. Not for a moment, however, do I regret my decision to liberate myself from the enslaving hold of emotion, for my life had been rendered meaningless by the selfish and profane love of another."

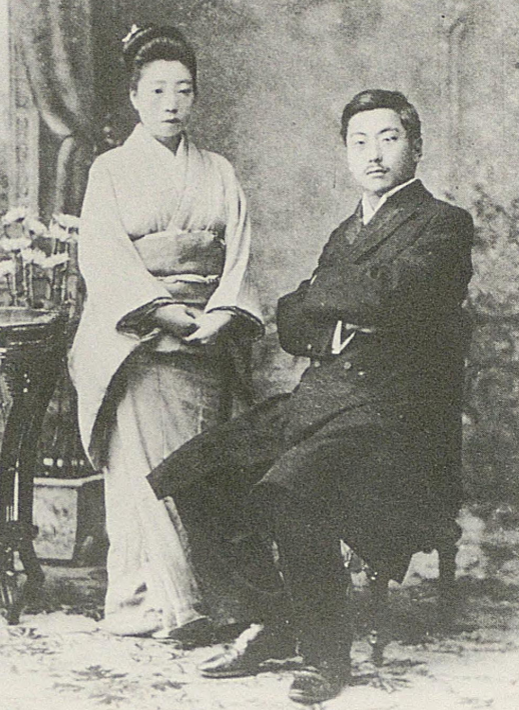

In 1901, she found a life partner in Hani Yoshikazu, a co-worker she had met at Hochi Shimbun. Their marriage marked the beginning of a profound personal and professional partnership. Shortly after their wedding, they both left Hochi Shimbun, with Yoshikazu taking a position at Takada Shimbunsha in Niigata, where they relocated. Their union formed the foundation for their collaborative efforts in founding Katei no Tomo (later Fujin no Tomo) in 1903 and Jiyu Gakuen in 1921. Yoshikazu later served as the head of Jiyu Gakuen, working alongside Motoko in their shared endeavors. Hani Motoko penned her autobiography, Speaking of Myself, in 1928, offering insights into her life experiences and philosophies.

7. Works

Hani Motoko was a prolific writer, and her works largely focused on themes of family, education, and women's roles, reflecting her broader philosophy. Her major publications include:

- Katei Kowabana (家庭小話, "Little Stories for the Home"), published in 1903 by Naigai Shuppan Kyokai.

- Ikuji no Shiori (育児之栞, "Bookmark for Child-Rearing"), published in 1905 by Naigai Shuppan Kyokai.

- Ikari ni Kakei o Seirisubeki ka (如何に家計を整理すべき乎, "How to Organize Household Accounts"), published in 1906 by Rokumeisha. This work was pivotal in popularizing the household ledger.

- Neru no Yuki (ネルの勇気, "Nell's Courage"), compiled as part of the Shojo Bunko (Girls' Library) series, published in 1907 by Aiyusha and others.

- Katei Mondai Meiryu Zadankai (家庭問題 名流座談, "Discussion on Family Issues by Notables"), compiled in 1907 by Aiyusha.

- Katei Kyoiku no Jikken (家庭教育の実験, "Experiments in Home Education"), published in 1908 by Katei no Tomosha and others.

- Jochu Kun (女中訓, "Maid's Instruction"), published in 1912 by Fujin no Tomosha.

- Akabo o Nakasezu ni Sodateru Hiketsu (赤坊を泣かせずに育てる秘訣, "Secrets to Raising Babies Without Crying"), published in 1912 by Fujin no Tomosha.

Beginning in 1927, Fujin no Tomosha began publishing the Hani Motoko Complete Works. A revised edition was released after World War II, initially comprising 20 volumes and later expanded to 21 volumes.

8. Death

Hani Motoko died on April 7, 1957. Her death was attributed to cerebral thrombosis followed by heart failure. She was laid to rest at Zōshigaya Cemetery in Tokyo, a tranquil resting place for many notable Japanese figures.

9. Legacy and Evaluation

Hani Motoko's life and work left an indelible mark on Japanese society, particularly in the spheres of journalism, women's empowerment, and education, though her legacy also includes aspects that invite critical discussion.

9.1. Positive Contributions

Hani Motoko's pioneering role as Japan's first female journalist opened doors for subsequent generations of women in the media. Her coverage of neglected social issues such as child care and orphanages demonstrated her commitment to social welfare and gave a voice to the vulnerable. Through Fujin no Tomo and her invention of the household ledger, she significantly improved the daily lives of countless Japanese women by promoting financial literacy, efficient home management, and a sense of empowerment within the domestic sphere. Her advocacy for the "Western-style housewife" concept, while seemingly conventional, was strategically reframed to emphasize independence, self-esteem, and personal freedom, challenging the prevailing notion of female inferiority and advocating for women's equal importance in society.

Furthermore, her establishment of Jiyu Gakuen laid the foundation for an innovative educational philosophy centered on holistic development, self-reliance, and the cultivation of strong moral character, providing girls with a unique learning environment that fostered leadership and practical skills. The enduring legacy of Jiyu Gakuen and the Fujin no Tomo Publishing House stand as testaments to her vision and enduring influence on Japanese education and publishing.

9.2. Criticisms and Controversies

While Hani Motoko is largely celebrated for her progressive contributions, some aspects of her activities have drawn critical perspectives. Notably, her cooperation with the government during the wartime regime, particularly in the lead-up to and during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937 onwards), is a point of debate. During this period, Hani and her followers, including her daughter Setsuko, actively participated in government initiatives aimed at urging women to "economize" and "rationalize" their daily lives. Critics argue that while this collaboration may have been driven by a desire to elevate women's position or a response to national pressures, it inadvertently lent support to a militaristic government and its policies. This cooperation, though framed by some as a pragmatic strategy to secure a better future for women within the state, highlights the complex choices made by public figures during times of national crisis and its potential implications for their broader social contributions.

10. Family and Relatives

Hani Motoko's family includes several notable individuals who made their own contributions to various fields.

- Husband: Hani Yoshikazu (羽仁吉一) - A key partner in her endeavors, he was an editor at Hochi Shimbun and later Takada Shimbunsha before co-founding Fujin no Tomo Publishing and serving as the head of Jiyu Gakuen.

- Sister: Chiba Kura (千葉くら) - The founder of Chiba Gakuen High School in Hachinohe, Aomori.

- Brother: Matsuoka Masao (松岡正男) - Held significant positions as president of Keijo Nippo, Mainichi Shinpo, and Jiji Shinpo. His daughter, Matsuoka Yoko (松岡洋子), became a renowned critic.

- Eldest Daughter: Hani Setsuko (羽仁説子) - Married to Hani Goro (羽仁五郎), a distinguished historian and Senator who played a crucial role in the establishment of the National Diet Library.

- Second Daughter: Hani Ryoko (羽仁凉子) - Tragically died at a young age due to illness.

- Third Daughter: Hani Keiko (羽仁惠子) - Remained unmarried and succeeded her parents as the second head of Jiyu Gakuen after their passing.

- Grandchildren:

- Hani Tatsuko (羽仁立子) - Also died in childhood due to illness.

- Hani Susumu (羽仁進)

- Hani Kyoko (羽仁協子)

- Hani Yuko (羽仁結子)

- Great-grandchildren:

- Hani Mio (羽仁未央) - A journalist.

- Hani Kanta (羽仁カンタ) - An environmental activist.