1. Overview

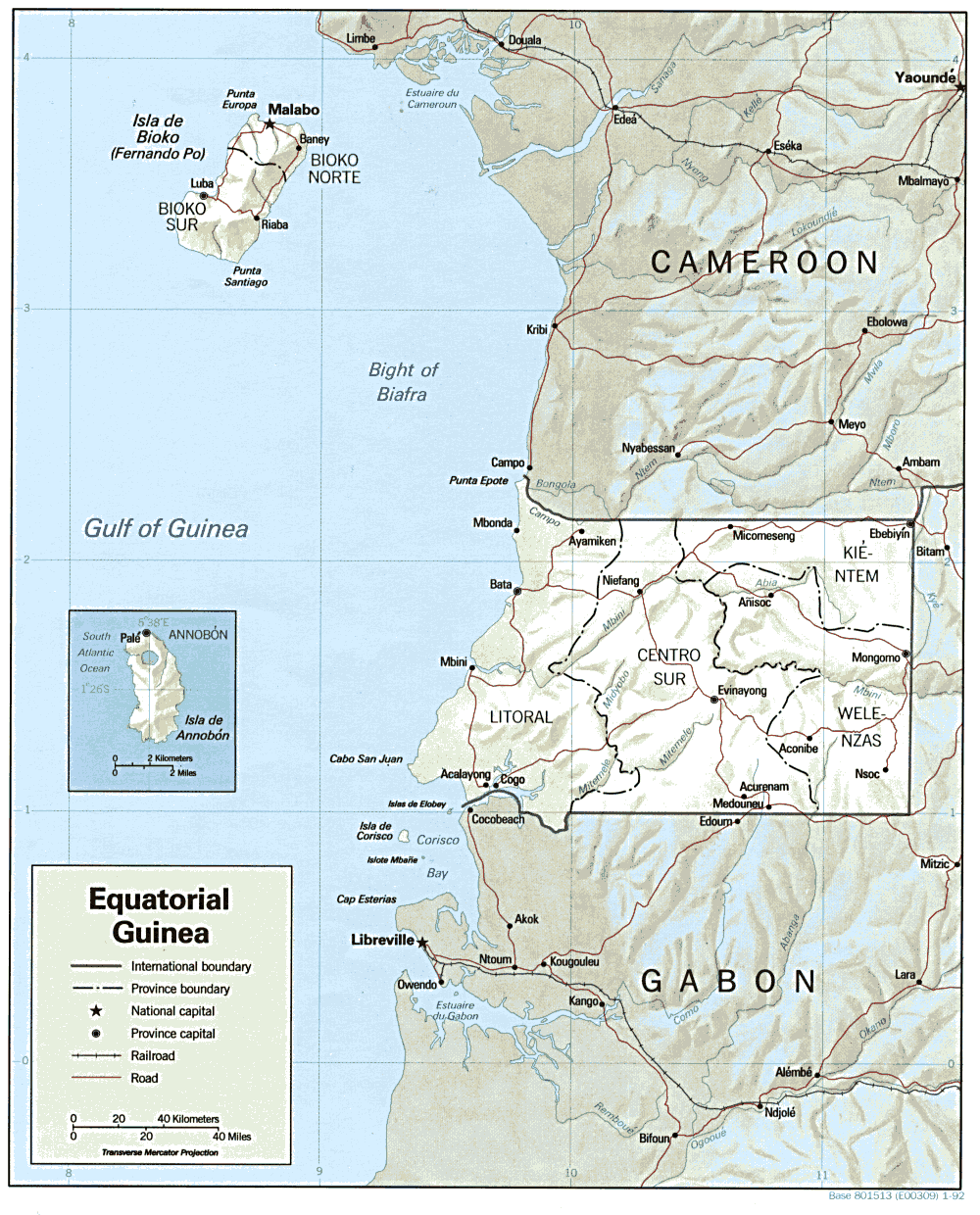

Equatorial Guinea (Spanish: Guinea EcuatorialEquatorial GuineaSpanish; French: Guinée équatorialeEquatorial GuineaFrench; Portuguese: Guiné EquatorialEquatorial GuineaPortuguese), officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (Spanish: República de Guinea EcuatorialRepublic of Equatorial GuineaSpanish; French: République de Guinée équatorialeRepublic of Equatorial GuineaFrench; Portuguese: República da Guiné EquatorialRepublic of Equatorial GuineaPortuguese), is a Central African nation comprising the mainland territory of Río Muni, bordered by Cameroon to the north and Gabon to the east and south, and several islands including Bioko (where the capital, Malabo, is located) and Annobón. Formerly a Spanish colony known as Spanish Guinea, it gained independence in 1968. The country's name reflects its proximity to both the Equator and the Gulf of Guinea, though no part of its mainland territory lies on the Equator. Spanish (EspañolSpanishSpanish) is the primary official language, unique in Africa. French (FrançaisFrenchFrench) and Portuguese (PortuguêsPortuguesePortuguese) also hold official status.

The nation's history is marked by a pre-colonial era of various indigenous groups, followed by Portuguese and then extensive Spanish colonization. Independence in 1968 led to the brutal dictatorship of Francisco Macías Nguema, characterized by severe human rights atrocities and economic collapse. He was overthrown in 1979 by his nephew, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who has ruled as president ever since. Obiang's regime, while overseeing significant economic growth due to large oil discoveries since the mid-1990s, is widely criticized for its authoritarian nature, pervasive corruption, severe human rights violations, and extreme wealth inequality. Despite having one of the highest per capita GDPs in Africa, a large portion of the population lives in poverty with limited access to basic services. This article examines Equatorial Guinea's geography, history, governance, economy, and society from a perspective that emphasizes social justice, human rights, and democratic development.

2. History

The history of Equatorial Guinea encompasses early inhabitation, Bantu migrations, European colonial domination by Portugal and Spain, a tumultuous independence, and a post-independence period marked by protracted authoritarian rule and the transformative discovery of oil.

2.1. Pre-colonial Era

The earliest inhabitants of the continental region now known as Equatorial Guinea were likely Pygmy peoples, remnants of whom are still found today in isolated pockets in southern Río Muni. Around 2,000 BC, migrations of Bantu-speaking peoples began from the region between southeastern Nigeria and northwestern Cameroon (the Grassfields). These groups, including the ancestors of the Bubi people and later the Fang people, gradually settled the mainland. By 500 BC, Bantu-speaking communities were established in continental Equatorial Guinea. The earliest archaeological evidence of settlements on Bioko Island dates to around AD 530. The Annobón population is believed to have originated from Angola, introduced by the Portuguese via São Tomé Island. These early societies developed their own distinct social and political structures prior to significant European contact.

2.2. European Colonization

The European colonial period in Equatorial Guinea was characterized by initial Portuguese exploration and claims, followed by a long period of Spanish rule that shaped the territory's future.

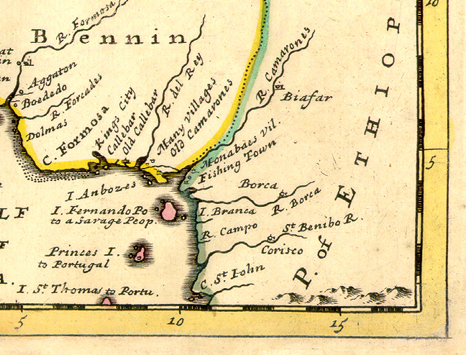

2.2.1. Portuguese Exploration and Early Claims (1472-1778)

The Portuguese explorer Fernão do Pó, while searching for a sea route to India, is credited as the first European to sight the island of Bioko in 1472. He named it "Formosa" (meaning "Beautiful"), but it soon became known by his own name, Fernando Pó. Portugal officially colonized Fernando Pó and Annobón Island in 1474. Recognizing the islands' potential with their volcanic soil and disease-resistant highlands, the Portuguese established their first factories (trading posts) around 1500. However, an initial attempt in 1507 to create a sugarcane plantation and town near present-day Concepción on Fernando Pó failed due to hostility from the indigenous Bubi people and the prevalence of fevers among the European settlers. The island's challenging climate, characterized by heavy rainfall, extreme humidity, and fluctuating temperatures, took a significant toll on early European settlers, and further colonization efforts were stalled for centuries.

2.2.2. Spanish Rule and British Lease (1778-1844)

In 1778, under the Treaty of El Pardo, Queen Maria I of Portugal ceded the islands of Fernando Pó (now Bioko) and Annobón, along with commercial rights to the Bight of Bonny (then Bight of Biafra) between the Niger River and the Ogoue River, to King Charles III of Spain. In exchange, Portugal received territories in South America, now part of western Brazil. Brigadier Felipe José, Count of Arjelejos, formally took possession of Bioko for Spain on October 21, 1778. However, after sailing to Annobón to also claim it, the Count died from a disease contracted on Bioko, and his fever-ridden crew mutinied. They landed on São Tomé Island, where they were imprisoned by Portuguese authorities, having lost over 80% of their men to sickness. This disaster made Spain hesitant to invest heavily in its new possessions. Nevertheless, the Spanish began to use the island as a base for slave trading on the nearby mainland. From 1778 to 1810, the territory that would become Equatorial Guinea was administered by the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, based in Buenos Aires.

Unwilling to commit significant resources to the development of Fernando Pó, Spain leased a base at Malabo on Bioko to the United Kingdom from 1827 to 1843. The British sought this base as part of their efforts to suppress the Atlantic slave trade. Without formal Spanish permission, the British moved the headquarters of the Mixed Commission for the Suppression of Slave Traffic to Fernando Pó in 1827, before returning it to Sierra Leone in 1843 under an agreement with Spain. Spain's abolition of slavery in 1817, at British insistence, had diminished the colony's perceived value to Spanish authorities, making the leasing of naval bases an attractive source of revenue from an otherwise unprofitable possession. An agreement for Spain to sell its African colony to the British was cancelled in 1841 due to opposition from Spanish public opinion and the Spanish Congress.

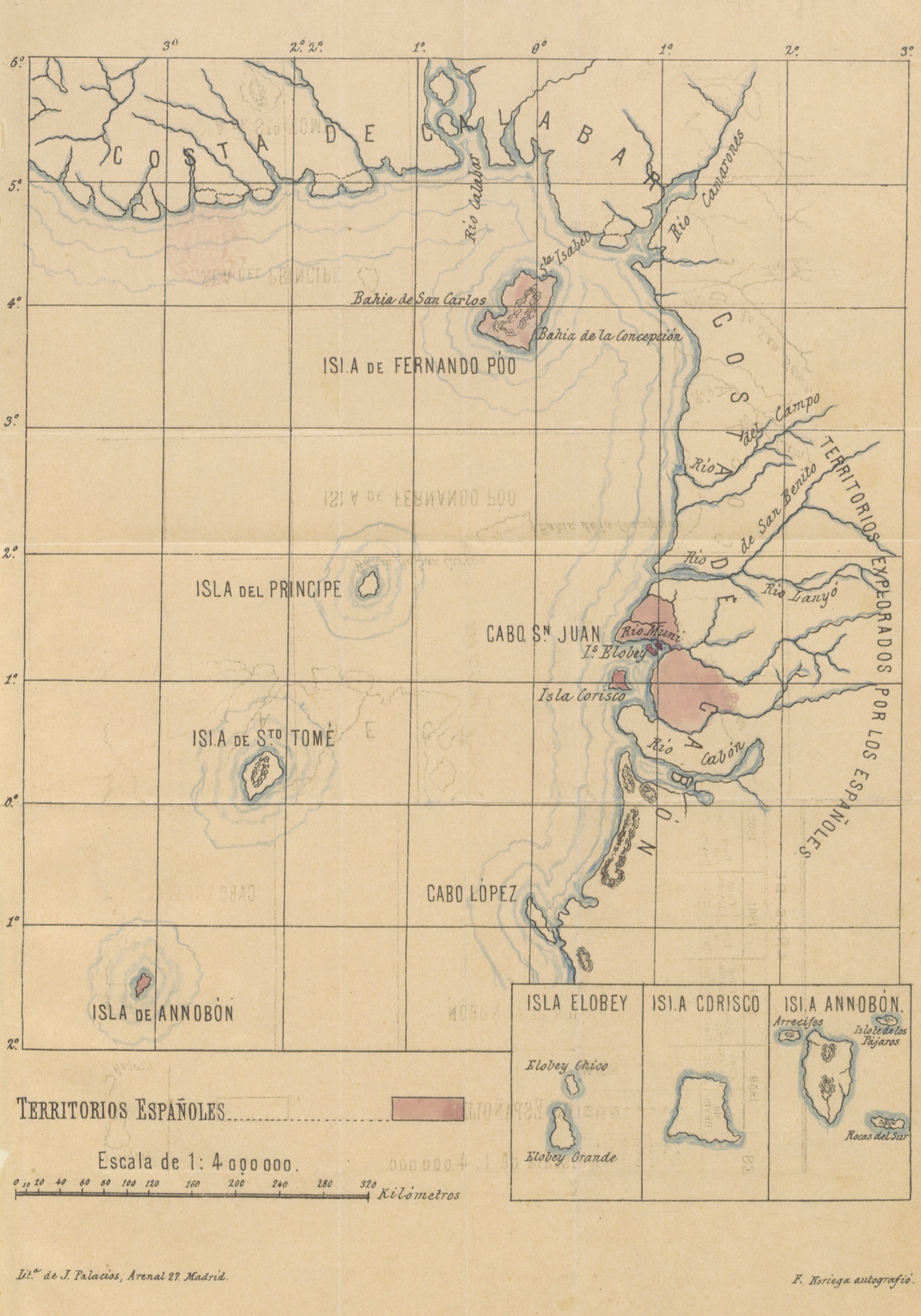

2.2.3. Consolidation of Spanish Colonial Rule (1844-1900)

In 1844, the British returned Fernando Pó (Bioko) to Spanish control, and the area became known as the "Territorios Españoles del Golfo de Guinea" (Spanish Territories of the Gulf of Guinea). Spain, however, did little to develop the colony, partly due to recurrent epidemics. In 1862, a severe outbreak of yellow fever killed many of the white settlers on the island. Despite these challenges, private citizens continued to establish plantations, primarily for cocoa and coffee, throughout the latter half of the 19th century.

The plantations on Fernando Pó were largely run by a Black Creole elite, later known as the Fernandinos. This group originated from about 2,000 Sierra Leoneans and freed slaves settled by the British during their lease period, supplemented by ongoing immigration from West Africa and the West Indies. Freed Angolan slaves, Portuguese-African Creoles, and immigrants from Nigeria and Liberia also settled in the colony and integrated into this new social stratum. Additionally, Cubans, Filipinos, Sephardic Jews, and Spaniards of various backgrounds, many of whom had been deported for political or other crimes, as well as some government-backed settlers, contributed to the diverse population.

By 1870, living conditions for Europeans on the island improved after recommendations to reside in the highlands. By 1884, much of the minimal colonial administration and key plantations had moved to Basilé, hundreds of meters above sea level. The explorer Henry Morton Stanley had criticized Spain for not "polishing this jewel" by failing to enact such a policy earlier. Despite these improvements, British traveler Mary Kingsley, who visited the island, still described Fernando Pó as "a more uncomfortable form of execution" for Spaniards assigned there.

There was also a continuous trickle of immigration from neighboring Portuguese islands, including escaped slaves and prospective planters. Although a few Fernandinos were Catholic and Spanish-speaking, by the eve of World War I, about nine-tenths were Protestant and English-speaking. Pidgin English became the island's lingua franca. Sierra Leoneans were particularly prominent as planters, benefiting from continued labor recruitment along the Windward Coast. The Fernandinos also established themselves as traders and intermediaries between the indigenous populations and the Europeans. William Pratt, a freed slave from the West Indies who had come via Sierra Leone, is credited with establishing the cocoa crop on Fernando Pó, which became crucial to the island's economy.

2.2.4. Early 20th Century (1900-1945)

Spain had not effectively occupied the large area in the Bight of Biafra to which it held treaty rights, and the French had been expanding their own colonial holdings at the expense of Spanish claims. Madrid only partially supported explorers like Manuel Iradier, who signed treaties in the interior extending towards Gabon and Cameroon. This left much of the land outside "effective occupation" as required by the 1885 Berlin Conference. Minimal government backing for mainland annexation resulted from a combination of shifting public opinion and the pressing need for labor on the plantations of Fernando Pó.

The Treaty of Paris (1900) ultimately left Spain with the continental enclave of Río Muni, an area of only 10 K mile2 (26.00 K km2), a fraction of the 116 K mile2 (300.00 K km2) extending east to the Ubangi River that the Spanish had initially claimed. The perceived humiliation of the Franco-Spanish negotiations, compounded by Spain's recent losses in the Spanish-American War (including Cuba), led Pedro Gover y Tovar, the head of the Spanish negotiating team, to commit suicide on his voyage home on October 21, 1901. Iradier himself died in despair in 1911; decades later, the port of Cogo was renamed Puerto Iradier in his honor.

Land regulations issued in 1904-1905 favored Spanish settlers, and most of the larger planters who arrived later came from Spain. To address labor shortages, an agreement was made with Liberia in 1914 to import cheap labor. However, due to severe malpractice and exploitation of Liberian workers on Fernando Pó, the Liberian government eventually terminated the treaty. This decision was heavily influenced by the Christy Report, which exposed the dire conditions of these workers and led to the downfall of Liberian President Charles D. B. King in 1930.

By the late nineteenth century, the indigenous Bubi people of Fernando Pó were somewhat protected from the demands of planters by Spanish Claretian missionaries. These missionaries became highly influential, organizing the Bubi into mission-controlled communities reminiscent of the Jesuit reductions in Paraguay. Catholic influence was further solidified following two small insurrections in 1898 and 1910, which protested the conscription of forced labor for plantations. The Bubi were disarmed in 1917 and became heavily dependent on the missionaries. Labor shortages were temporarily eased by a massive influx of refugees from German Kamerun during World War I, along with thousands of white German soldiers who remained on the island for several years.

Between 1926 and 1959, Bioko (then Fernando Pó) and Río Muni were united as the colony of Spanish Guinea. The economy relied on large cacao and coffee plantations and logging concessions. The workforce was predominantly immigrant contract labour from Liberia, Nigeria, and Cameroun. Between 1914 and 1930, an estimated 10,000 Liberians went to Fernando Pó under the labor treaty that was stopped in 1930. With Liberian workers no longer available, planters on Fernando Pó turned to Río Muni for labor. Campaigns were mounted to subdue the Fang people in the 1920s, coinciding with Liberia's cutback on recruitment. By 1926, garrisons of the colonial guard were established throughout the enclave, and the entire colony was declared 'pacified' by 1929.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a significant impact on the colony. A group of 150 Spanish whites, including the Governor-General and Vice-Governor-General of Río Muni, created a socialist party called the Popular Front in the enclave, opposing the interests of the Fernando Pó plantation owners. When the war broke out, Francisco Franco ordered Nationalist forces based in the Canary Islands to secure control over Equatorial Guinea. In September 1936, Nationalist forces, backed by Falangists from Fernando Pó, took control of Río Muni, which, under Governor-General Luiz Sanchez Guerra Saez and his deputy Porcel, had initially supported the Republican government. By November, the Popular Front and its supporters had been defeated, and Equatorial Guinea was secured for Franco. The commander in charge of the occupation, Juan Fontán Lobé, was appointed Governor-General by Franco and began to exert more direct Spanish control over the interior of the enclave.

Río Muni officially had a population of just over 100,000 in the 1930s, and escape into French Cameroun or Gabon was relatively easy for those seeking to avoid forced labor or colonial rule. Fernando Pó, therefore, continued to suffer from labor shortages. The French only briefly permitted recruitment in Cameroun. The main source of labor subsequently became Igbo people, who were often smuggled in canoes from Calabar in Nigeria. This new labor supply allowed Fernando Pó to become one of Africa's most productive agricultural areas after World War II.

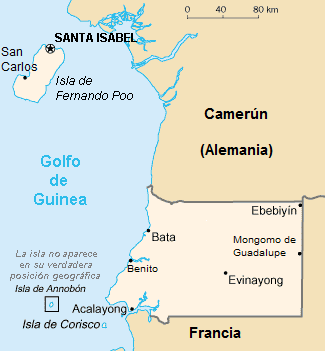

2.2.5. Late Spanish Rule and Path to Independence (1945-1968)

The post-World War II colonial history of Equatorial Guinea can be divided into three distinct phases. The first, lasting until 1959, saw its status elevated from "colony" to "province" of Spain, mirroring the approach of the Portuguese Empire in its territories. This phase was largely a continuation of previous policies, which closely resembled those of Portugal and France, notably in dividing the population into a vast majority governed as 'natives' or non-citizens, and a very small minority (along with whites) admitted to civic status as emancipados. Assimilation into metropolitan Spanish culture was the only permissible path for advancement for the African population.

The second phase, from 1960 to 1968, involved Madrid attempting a partial decolonisation aimed at keeping the territory as an integral part of the Spanish system. This "provincial" phase saw the beginnings of nationalism, primarily among small groups who had taken refuge from the Franco regime's paternalistic rule in neighboring Cameroun and Gabon. Two main nationalist bodies emerged: the Movimiento Nacional de Liberación de la Guinea Ecuatorial (MONALIGE), led by figures like Atanasio Ndongo Miyone, and the Idea Popular de Guinea Ecuatorial (IPGE).

By the late 1960s, much of the African continent had gained independence. Aware of this global trend, Spain began to increase efforts to prepare the country for self-governance. In 1965, the gross national product per capita was $466, the highest in Black Africa at the time. Spain had invested in infrastructure, constructing an international airport at Santa Isabel (Malabo), a television station, and improving the literacy rate to a reported 89%. By 1967, the number of hospital beds per capita in Equatorial Guinea was claimed to be higher than in Spain itself, with 1,637 beds across 16 hospitals. However, despite these material improvements, by the end of colonial rule, the number of Africans in higher education remained extremely low, only in the double digits, indicating a severe lack of investment in human capital and leadership development.

A decision on August 9, 1963, approved by a referendum on December 15, 1963, granted the territory a measure of autonomy and led to the administrative promotion of a 'moderate' group, the Movimiento de Unión Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial (MUNGE). This initiative proved unsuccessful in stemming the tide of nationalism. With growing pressure for change from the United Nations, Madrid was gradually forced to concede to nationalist demands. Two General Assembly resolutions were passed in 1965 ordering Spain to grant independence to the colony. In 1966, a UN Commission toured the country and recommended the same.

In response, Spain announced a constitutional convention on October 27, 1967, to negotiate a new constitution for an independent Equatorial Guinea. The conference was attended by 41 local delegates and 25 Spaniards. The African delegates were principally divided: the Fernandinos and Bubi from Fernando Pó feared a loss of their privileges and being overwhelmed by the Fang majority from Río Muni, while the Río Muni Fang nationalists sought a unified, independent state. At the conference, the leading Fang figure and later first president, Francisco Macías Nguema, gave a controversial speech in which he reportedly claimed that Adolf Hitler had "saved Africa." After nine sessions, the conference was suspended due to a deadlock between "unionists" and "separatists" who wanted a separate Fernando Pó. Macías traveled to the UN to bolster international awareness of the independence issue, and his speeches in New York contributed to Spain setting a date for both independence and general elections. In July 1968, virtually all Bubi leaders went to the UN in New York to try and raise awareness for their cause, advocating for autonomy or a separate status for Bioko, but the international community was largely uninterested in the specifics, focused instead on the broader goal of decolonization. The prevailing optimism of the 1960s regarding the future of former African colonies meant that groups perceived as close to European rulers, like the Bubi, were not viewed positively by many emerging African nations or international bodies.

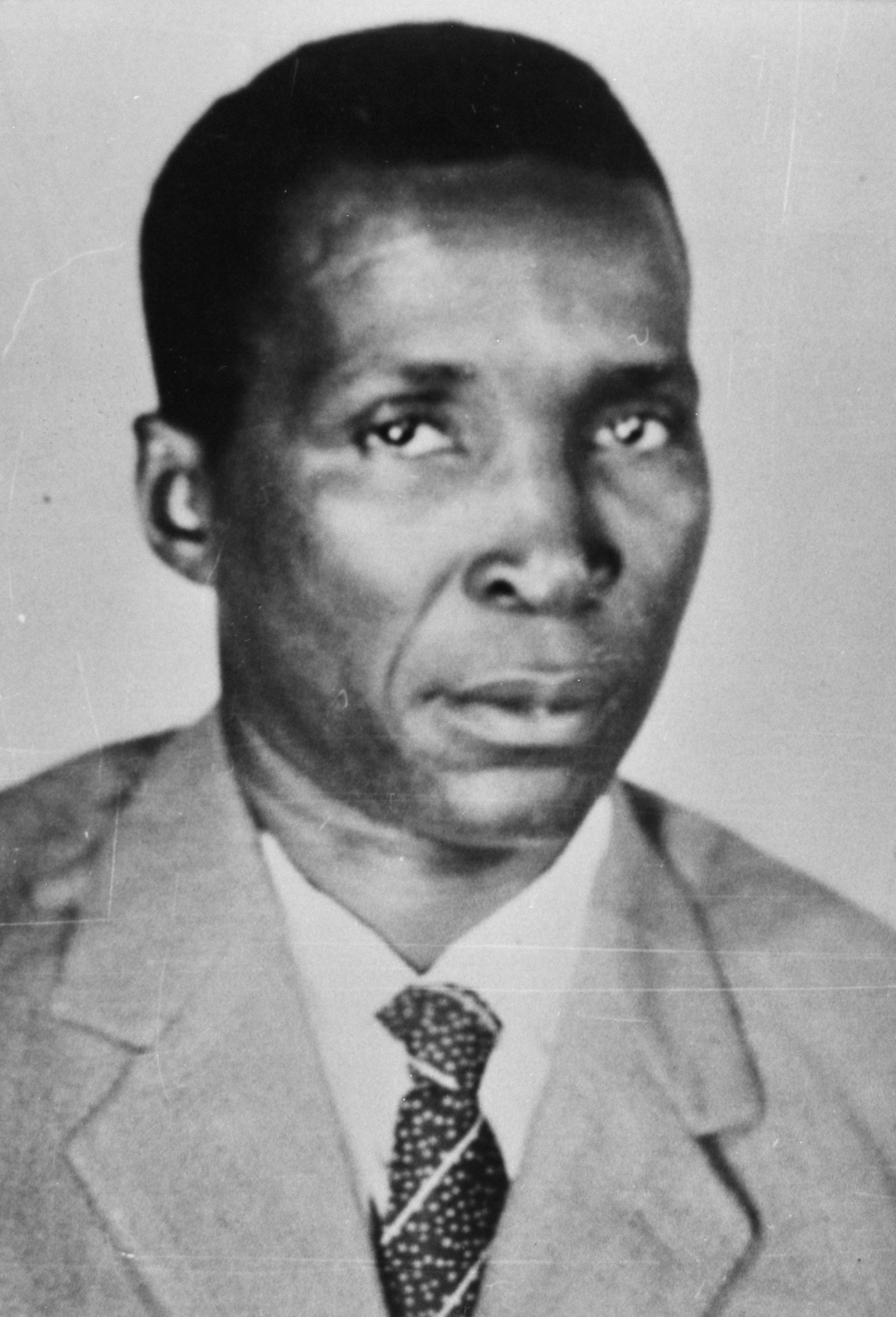

2.3. Independence and Macías Nguema Regime (1968-1979)

Equatorial Guinea gained independence from Spain on October 12, 1968. The new country became the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, and this date is celebrated as its Independence Day. Francisco Macías Nguema became president following the country's only free and fair election to date. The Spanish government under Francisco Franco had initially backed Macías, believing him to be manageable; much of his campaigning involved visiting rural areas of Río Muni and making populist promises. He won in the second round of voting.

Shortly after independence, during the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), Fernando Pó (Bioko) hosted many Biafra-supporting Ibo migrant workers, and numerous refugees from the secessionist state fled to the island. The International Committee of the Red Cross began running relief flights from Equatorial Guinea. However, Macías soon shut down these operations, reportedly refusing to allow them to fly in diesel fuel for their trucks or oxygen tanks for medical operations, contributing to the humanitarian crisis that ultimately led to Biafra's surrender.

Macías Nguema rapidly consolidated power and established a totalitarian dictatorship. After the Public Prosecutor complained about "excesses and maltreatment" by government officials, Macías had approximately 150 alleged coup-plotters, mostly political opponents, executed in a purge on Christmas Eve 1969. In July 1970, he outlawed all opposition political parties, establishing a one-party state under his National United Workers' Party. In 1972, he declared himself President for life.

His regime severed ties with Spain and Western countries, while paradoxically condemning Marxism as "neo-colonialist" yet maintaining special relations with communist states, notably China, Cuba, East Germany, and the Soviet Union. Macías Nguema signed a preferential trade agreement and a shipping treaty with the Soviet Union, which also provided loans. The shipping agreement granted the Soviets permission for a pilot fishery development project and a naval base at Luba. In return, the USSR was to supply fish. China and Cuba also provided various forms of financial, military, and technical assistance, gaining influence in the country. Access to the Luba base and later to Malabo International Airport proved advantageous for the USSR during the Angolan Civil War.

The Macías Nguema regime was characterized by extreme brutality and human rights atrocities. In 1974, the World Council of Churches affirmed that large numbers of people had been murdered since 1968 in an ongoing reign of terror. They reported that a quarter of the entire population had fled abroad, while "the prisons are overflowing and to all intents and purposes form one vast concentration camp." Out of a population of approximately 300,000, an estimated 50,000 to 80,000 were killed. Macías Nguema was accused of committing genocide against the ethnic minority Bubi people. He ordered the deaths of thousands of suspected opponents, closed down churches, and presided over the collapse of the economy as skilled citizens and foreigners fled the country. His rule earned Equatorial Guinea the grim moniker "the Dachau of Africa."

2.4. Obiang Regime (1979-present)

On August 3, 1979, Francisco Macías Nguema was overthrown in a bloody coup d'état led by his nephew, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, who had been serving as a military governor and head of the National Guard. Over two weeks of civil war ensued until Macías Nguema was captured. He was tried and executed shortly afterward, on September 29, 1979. Teodoro Obiang assumed the presidency, initially as head of a Supreme Military Council, and has remained in power ever since, becoming one of Africa's longest-serving leaders. While his regime has been less overtly violent than his uncle's in its early years, it is widely characterized as an entrenched authoritarian dictatorship with a dire human rights record and systemic corruption.

The discovery of significant offshore oil reserves by American company Mobil in 1995, and subsequent exploitation starting in the mid-1990s, dramatically transformed Equatorial Guinea's economy. The country became one of Sub-Saharan Africa's largest oil producers, leading to a massive increase in GDP and government revenue. It subsequently became the richest country per capita in Africa. However, this newfound wealth has been extremely unevenly distributed. While President Obiang, his family, and a small elite have amassed enormous fortunes, the majority of the population continues to live in poverty, with limited access to basic services such as clean drinking water, healthcare, and education. The country consistently ranks low on the United Nations Human Development Index. For example, in 2019, it ranked 144th, with reports indicating that less than half the population had access to clean drinking water and 7.9% of children died before the age of five. This stark contrast between high per capita income and poor social indicators exemplifies the "resource curse".

President Obiang's rule has been maintained through the dominance of his Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE), suppression of political dissent, control over the media, and elections widely regarded by international observers as fraudulent. Numerous alleged coup attempts have been reported over the decades, often followed by crackdowns on perceived opponents. Political freedoms are severely restricted, and space for civil society is minimal. Corruption is pervasive, with frequent accusations that oil revenues are systematically siphoned off by the ruling elite. Forbes magazine estimated President Obiang's personal wealth at 600.00 M USD in 2006. Investigations, such as the 2004 U.S. Senate inquiry into Riggs Bank, revealed large sums of money being diverted to accounts controlled by Obiang and his associates.

In 2011, the government announced plans for a new capital city, initially named Oyala, located in the rainforest of the mainland. The city was renamed Ciudad de la Paz ("City of Peace") in 2017 and is being constructed with substantial investment, though its development has also faced criticism for its cost and lack of transparency.

Despite consistent international criticism regarding human rights abuses, lack of democracy, and corruption from organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Reporters Without Borders (which has ranked Obiang among its "predators" of press freedom), Equatorial Guinea has maintained diplomatic and economic ties with various countries, particularly those involved in its oil sector. The country became a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council for the 2018-2019 term.

On March 7, 2021, a series of munition explosions at a military base near Bata, the country's economic hub, resulted in at least 98 deaths and over 600 injuries, highlighting issues of public safety and military infrastructure management. In November 2022, President Obiang was re-elected in the 2022 Equatorial Guinean general election with a reported 99.7% of the vote, amid widespread accusations of fraud and repression from the fragmented opposition. His long-standing rule continues to be a defining feature of Equatorial Guinea's political landscape, with little prospect for democratic reform or improved social justice under the current system.

3. Geography

Equatorial Guinea is located on the west coast of Central Africa. The country comprises a mainland territory, Río Muni, and an insular region consisting of several islands in the Gulf of Guinea.

3.1. Topography and Location

Equatorial Guinea consists of a mainland territory, Río Muni, and five main islands: Bioko, Annobón, Corisco, Elobey Grande, and Elobey Chico.

Río Muni makes up the continental portion, bordered by Cameroon to the north and Gabon to the east and south. Its coastline is on the Gulf of Guinea. The terrain is characterized by a coastal plain rising to interior hills and plateaus. Major rivers include the Benito River (Mbini) and the Muni River estuary on the southern border.

Bioko Island (formerly Fernando Pó) is the largest island, located about 25 mile (40 km) off the coast of Cameroon. It is volcanic in origin and mountainous, with Pico Basilé (formerly Mount Santa Isabel) being its highest point at 9.9 K ft (3.01 K m). The capital city, Malabo, is situated on Bioko's northern coast.

Annobón Island is a small volcanic island located about 217 mile (350 km) west-south-west of Cape Lopez in Gabon and about 96 mile (155 km) south of the Equator, making it the only part of Equatorial Guinea in the Southern Hemisphere.

Corisco Island and the smaller islands of Elobey Grande and Elobey Chico are situated in Corisco Bay, near the Muni River estuary and the border with Gabon.

Equatorial Guinea lies between latitudes 4°N and 2°S, and longitudes 5°E and 12°E. Despite its name, no part of the country's mainland territory lies on the Equator; the Equator passes between Río Muni and Annobón Island.

3.2. Climate

Equatorial Guinea has a tropical climate, characterized by high temperatures, high humidity, and significant rainfall throughout the year. There are distinct wet and dry seasons, though these vary between the mainland and the islands.

On the mainland (Río Muni), the dry season typically runs from June to August, while the rest of the year is wet. The average temperature is around 80.6 °F (27 °C). Rainfall is heavier along the coast than inland.

On Bioko Island, the pattern is reversed: it is wet from June to August and drier from December to February. Malabo, on Bioko, has an average annual rainfall of about 0.1 K in (1.93 K mm), with temperatures ranging from 60.8 °F (16 °C) to 91.4 °F (33 °C). The southern part of Bioko, particularly around Ureka, is one of the wettest places in Africa, with annual rainfall potentially exceeding 0.4 K in (10.92 K mm) due to monsoonal influences. Normal high temperatures on the southern Moka Plateau are cooler, around 69.8 °F (21 °C).

Annobón Island experiences rain or mist almost daily, and a completely cloudless day is reportedly never registered there. Overall, the climate supports lush tropical vegetation across the country.

3.3. Ecology and Wildlife

Equatorial Guinea possesses a rich biodiversity, spanning several distinct ecoregions due to its varied geography of mainland rainforests, volcanic islands, and coastal areas. The country's ecosystems face challenges from human activities, including resource extraction.

The mainland region of Río Muni lies primarily within the Atlantic Equatorial coastal forests ecoregion, characterized by dense rainforest. Patches of Central African mangroves are found along the coast, particularly in the Muni River estuary.

Bioko Island hosts parts of two ecoregions: the Cross-Sanaga-Bioko coastal forests cover most of the island and adjacent mainland areas in Cameroon and Nigeria, while the Mount Cameroon and Bioko montane forests ecoregion encompasses the highlands of Bioko and nearby Mount Cameroon. These montane forests are home to unique flora and fauna adapted to higher altitudes.

Annobón Island, along with São Tomé and Príncipe, forms part of the São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón moist lowland forests ecoregion, known for its high levels of endemism.

Equatorial Guinea's forests are home to a diverse range of wildlife, including primates such as gorillas, chimpanzees, and various monkey species. Other notable mammals include leopards, forest buffalo, various antelope species, forest elephants, and hippopotamuses (though populations may be diminished). Reptiles like crocodiles and various snakes, including pythons, are also present. The country's avifauna is rich, with many forest-dependent bird species.

Additional descriptive text related to these specific ecological areas and their features should be inserted here to enhance context and break the image sequence.

Further descriptive text regarding forest ecosystems, perhaps detailing specific flora or conservation challenges related to these depicted areas, should be added here.

The country has established national parks and protected areas, such as Monte Alén National Park in Río Muni and the Pico Basilé National Park on Bioko, in an effort to conserve its biodiversity. However, conservation efforts face significant challenges. Deforestation due to logging (both legal and illegal), expansion of agriculture, and infrastructure development pose threats to forest ecosystems. The oil and gas industry, while crucial to the economy, also presents environmental risks, including potential pollution and habitat disruption in coastal and marine areas. Bushmeat hunting is another pressure on wildlife populations. The country had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.99/10, ranking it 30th globally out of 172 countries, indicating that while significant forest cover remains, human pressures are evident.

The country's flora is rich, supporting a variety of animal species. Agricultural practices, as shown by soybean cultivation, also play a role in the ecological landscape.

The faunal diversity extends from small reptiles like chameleons to vibrant birdlife such as turacos.

4. Administrative Divisions

Equatorial Guinea is divided into provinces, which are the primary administrative subdivisions of the country.

4.1. Provinces and Major Cities

Equatorial Guinea is divided into eight provinces (provincias). The newest province is Djibloho, created in 2017, where the planned new capital, Ciudad de la Paz, is located. The provinces are further subdivided into 19 districts and 37 municipalities.

The eight provinces are (capitals in parentheses):

# Annobón (San Antonio de Palé) - An island in the South Atlantic.

# Bioko Norte (North Bioko) (Malabo) - Northern part of Bioko Island, location of the national capital.

# Bioko Sur (South Bioko) (Luba) - Southern part of Bioko Island.

# Centro Sur (Center-South) (Evinayong) - Central-southern part of Río Muni.

# Djibloho (Ciudad de la Paz) - A new province in central Río Muni, established to host the future capital.

# Kié-Ntem (Ebebiyín) - Northeastern part of Río Muni, bordering Cameroon and Gabon.

# Litoral (Coast) (Bata) - Coastal region of Río Muni, location of the country's largest city and economic hub.

# Wele-Nzas (Mongomo) - Southeastern part of Río Muni, bordering Gabon; hometown of President Obiang.

Major Cities:

- Malabo: Located on Bioko Island, it is the current national capital and a major commercial and financial center, particularly for the oil industry.

- Bata: Situated on the coast of Río Muni, Bata is the largest city in Equatorial Guinea by population and serves as the primary economic and transport hub for the mainland region.

- Ciudad de la Paz: Formerly Oyala, this city is under construction in the province of Djibloho in Río Muni and is planned to be the future capital of the country.

- Ebebiyín: A significant town in the northeast of Río Muni, near the borders with Cameroon and Gabon.

- Mongomo: A town in the east of Río Muni, known as the birthplace of President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo and featuring a large basilica.

- Luba: Located on Bioko Island, it is the capital of Bioko Sur province and has port facilities.

5. Government and Politics

Equatorial Guinea's political system is formally a presidential republic, but in practice, it operates as a highly centralized authoritarian state. The country has been dominated by President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo and his party, the Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE), since 1979. The political environment is characterized by a severe lack of democratic freedoms, systemic corruption, and significant human rights concerns.

5.1. Governmental Structure

According to the Constitution (revised most recently in 2011), Equatorial Guinea is a presidential republic.

The Executive Branch is headed by the President, who is both the head of state and head of government. The president holds extensive powers, including appointing and dismissing the prime minister and other cabinet members, making laws by decree, dissolving the legislature, negotiating and ratifying treaties, and serving as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has been in power since 1979. The 2011 constitution introduced a limit of two seven-year terms for the president, but it was stated this would not apply retroactively to Obiang's previous terms. The constitution also created the post of Vice President, often filled by a close relative of the president, such as his son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue.

The Legislative Branch is bicameral, consisting of:

- The Chamber of Deputies (lower house): Composed of 100 members elected by popular vote for five-year terms.

- The Senate (upper house): Introduced in the 2011 constitution, it has 70 members. Fifty-five senators are elected by the people, and the remaining 15 are designated by the president. Senators also serve five-year terms.

In practice, the legislature is dominated by the ruling PDGE party and has limited independent power, largely rubber-stamping presidential decrees and policies.

The Judicial Branch is nominally independent but is widely considered to be under the influence of the executive branch. The highest court is the Supreme Court. The judiciary often fails to provide due process, and political interference in legal matters is common, particularly in cases involving human rights or political opposition.

5.2. Political Landscape and Human Rights

The political landscape of Equatorial Guinea is overwhelmingly dominated by President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo and his Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (PDGE), which has been in power since its formation in 1987 (effectively since Obiang took power in 1979). The country is characterized by authoritarianism, systemic corruption, and a deeply problematic human rights record.

President Obiang maintains his grip on power through a combination of patronage networks fueled by oil wealth, control over state institutions (including the judiciary, security forces, and media), and the severe repression of dissent. Elections, both presidential and parliamentary, are regularly held but are consistently criticized by international observers and opposition groups as being neither free nor fair, often marked by irregularities, intimidation, and results showing overwhelming victories for Obiang and the PDGE. For instance, in the 2022 general elections, the PDGE reportedly won all 100 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and all elected seats in the Senate.

Political opposition is extremely weak and fragmented. Opposition parties exist legally, such as the Convergence for Social Democracy (CPDS), but they operate under severe restrictions. Their activities are often hampered by harassment, arrests, and the denial of permits for rallies or meetings. Many opposition figures operate in exile, primarily in Spain. There is virtually no space for independent civil society organizations or critical media. Most media outlets are state-controlled or owned by individuals close to the president, and self-censorship is widespread. Freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly are severely curtailed.

The human rights situation in Equatorial Guinea is dire and consistently ranks among the worst in the world. Reports from organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the U.S. Department of State document a wide range of abuses, including:

- Arbitrary arrests and detentions, often of political opponents, activists, and journalists.

- Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of detainees by security forces.

- Lack of due process and fair trial standards, with a judiciary susceptible to executive influence.

- Restrictions on political freedoms, including the rights to associate and express dissenting opinions.

- Harassment and intimidation of human rights defenders and independent journalists.

- Corruption is endemic at all levels of government and is a major factor in the mismanagement of the country's vast oil wealth. Transparency International consistently ranks Equatorial Guinea among the most corrupt countries globally. This corruption deprives the majority of the population of the benefits of oil revenue, leading to extreme wealth inequality. While a small elite connected to the regime enjoys immense wealth, a large percentage of Equatoguineans live in poverty, lacking access to adequate healthcare, education, clean water, and sanitation. This disparity highlights the profound social impact of governance failures and the inequitable distribution of state resources. Issues affecting minorities and vulnerable groups, while not always the primary focus of international reports, are also a concern within the broader context of rights suppression.

Despite signing an anti-torture decree and undertaking some prison renovations, substantive improvements in the human rights situation have not materialized. The government often dismisses international criticism as interference in its internal affairs.

5.3. Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of Equatorial Guinea (Fuerzas Armadas de Guinea Ecuatorial) are responsible for national security and defense. The total active personnel is estimated to be around 2,500 members. The military is divided into several branches:

- Army: The largest branch, with approximately 1,400 soldiers. Its primary role is land-based defense and internal security.

- Navy: Comprising about 200 personnel, the navy's responsibilities include maritime patrol, particularly important given the country's offshore oil installations in the Gulf of Guinea.

- Air Force: A small branch with around 120 members, operating a limited number of aircraft for transport and reconnaissance.

- Gendarmerie/Police: There is also a paramilitary police force of about 400 members, and a separate gendarmerie whose numbers are not precisely known. These forces play a significant role in internal security and maintaining public order, often implicated in human rights abuses.

The armed forces are primarily tasked with defending the nation's sovereignty, protecting its territorial integrity, and supporting internal security operations. Given the country's oil wealth, a key focus is the protection of offshore oil and gas infrastructure. The military leadership is closely tied to President Obiang's regime. There have been reports of foreign military assistance and training, including from countries like Morocco (historically providing presidential guard elements) and the US-based private military company Military Professional Resources Inc. (MPRI), which was contracted in the past to train police forces. Despite these efforts, the armed forces, like other state institutions, are often viewed as instruments for maintaining the current regime's power rather than solely serving national defense interests. The 2024 Global Peace Index ranked Equatorial Guinea as the 94th most peaceful country in the world.

5.4. Foreign Relations

Equatorial Guinea's foreign policy is primarily shaped by its economic interests, particularly its oil and gas sector, and its efforts to maintain the stability of President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo's long-standing regime. The country aims to cultivate relationships that support these objectives while navigating international scrutiny over its human rights record and governance issues.

Key aspects of its foreign relations include:

- Relations with Former Colonial Powers**: Spain and France, the former colonial powers, maintain significant, albeit sometimes complex, relationships with Equatorial Guinea. Spain is a key trading partner and a destination for many Equatoguinean expatriates and opposition figures. France also has economic and cultural ties, and Equatorial Guinea is a member of the Francophonie.

- Relations with Oil-Investing Nations**: The United States has been a major partner due to the involvement of American companies (like ExxonMobil, Marathon Oil, Chevron) in Equatorial Guinea's oil industry. Despite human rights concerns consistently raised by the U.S. Department of State, pragmatic engagement related to energy security and investment has often characterized the relationship. China has also become an increasingly important economic partner, involved in infrastructure projects.

- Regional Relations**: Equatorial Guinea is a member of the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). Relations with neighbors Cameroon and Gabon have historically included cooperation but also periods of tension, particularly over maritime border disputes and resource claims in the oil-rich Gulf of Guinea.

- Membership in International Organizations**:

- United Nations (UN): Equatorial Guinea is a UN member and served as a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council for the 2018-2019 term.

- OPEC: It became a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries in 2017, reflecting its status as a significant oil producer.

- CPLP (Lusophony): Equatorial Guinea was controversially admitted as a full member in 2014, despite Portuguese not being widely spoken. This move was seen as an attempt by the Obiang government to diversify its international alliances and improve its image. Membership required commitments to promote Portuguese and improve human rights, though progress on the latter has been minimal.

- Francophonie: Membership in this organization of French-speaking countries underscores its ties with France and other Francophone African nations.

- Central African Monetary and Economic Union (CEMAC): As a member, Equatorial Guinea uses the CFA franc and participates in regional economic integration efforts.

- International Scrutiny**: Equatorial Guinea faces persistent international criticism from human rights organizations (e.g., Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch), foreign governments, and international bodies regarding its poor human rights record, lack of democratic freedoms, widespread corruption, and the opaque management of oil revenues. The government typically dismisses such criticism as biased or an infringement on its sovereignty. Despite this scrutiny, the strategic importance of its oil reserves has often led many international actors to maintain engagement, balancing human rights concerns with economic and geopolitical interests.

6. Economy

The economy of Equatorial Guinea has been overwhelmingly dominated by its oil and gas sector since the mid-1990s, which transformed it from a small, agriculture-based economy into one of Africa's largest oil producers. However, this wealth has not translated into broad-based development or improved living standards for the majority of the population due to severe inequality and corruption.

6.1. Pre-Oil Economy

Before the discovery and large-scale exploitation of oil reserves, Equatorial Guinea's economy was primarily based on agriculture and forestry. The main export crops were cocoa, primarily grown on Bioko Island, and coffee, along with timber extracted from the mainland forests of Río Muni. These commodities were mostly exported to Spain, the colonial ruler, and to a lesser extent, Germany and the UK. Subsistence farming was the mainstay for much of the rural population. On January 1, 1985, Equatorial Guinea became the first non-Francophone African member of the franc zone, adopting the CFA franc as its currency, replacing the national currency, the ekwele, which had previously been linked to the Spanish peseta. The pre-oil economy was modest, and the country was relatively poor.

6.2. Oil and Gas Industry

The discovery of large offshore oil reserves in 1995/1996, notably the Zafiro field by Mobil (now ExxonMobil), and later other significant fields like Alba (gas and condensate) and Ceiba, dramatically reshaped Equatorial Guinea's economy. By the mid-2000s, the country had become the third-largest oil producer in Sub-Saharan Africa, with production peaking at over 360,000 barrels per day. This led to an extraordinary surge in government revenue and GDP growth, making Equatorial Guinea one of the richest countries in Africa on a per capita basis for a period. Major international oil companies, including ExxonMobil, Marathon Oil, Kosmos Energy, and Chevron, have been central to the development and operation of the hydrocarbon sector.

The oil and gas industry accounts for the vast majority of Equatorial Guinea's export revenues (around 97% in some years) and government income. While it has fueled significant infrastructure projects, particularly in Malabo and the planned new capital, Ciudad de la Paz, the benefits have been highly concentrated. The industry is capital-intensive and employs relatively few local citizens directly.

The environmental impact of oil and gas extraction includes risks of pollution in marine and coastal ecosystems. Social impacts have been complex; while generating immense wealth for the state and a ruling elite, it has also been linked to increased corruption, social inequalities, and the neglect of other economic sectors, a phenomenon often described as the "resource curse". Fluctuations in global oil prices also make the economy highly vulnerable.

6.3. Economic Structure, Inequality, and Challenges

Equatorial Guinea's economic structure is overwhelmingly dependent on its oil and gas sector, which, while generating substantial national income, has also created profound challenges, most notably extreme wealth inequality and systemic corruption. Despite having one of the highest GNI per capita figures in Africa (e.g., $21,517 GDP per capita in 2016 according to one UN report, though figures vary), this wealth is not reflected in the living standards of the majority of the population.

A significant portion of Equatoguineans live in poverty. Reports have indicated that up to 70% of the population lived on less than one dollar a day at certain periods during the oil boom. Access to basic services like clean water, sanitation, healthcare, and quality education remains severely limited for many. The country consistently ranks poorly on the United Nations Human Development Index (e.g., 145th out of 189 in 2019), underscoring the disconnect between oil wealth and human development. The Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality, has been reported as very high (e.g., 58.8 in 2022), indicating one of the most unequal distributions of income in the world.

Corruption is a pervasive issue, with numerous reports and investigations (such as the 2004 U.S. Senate investigation into Riggs Bank) suggesting that state oil revenues are systematically siphoned off by President Obiang, his family, and senior regime officials. This kleptocratic governance is a primary reason why oil wealth has not translated into broad-based societal benefits. Transparency International consistently ranks Equatorial Guinea among the countries with the highest perceived levels of public sector corruption (e.g., a score of 16 out of 100, ranking 174th out of 180 countries in its 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index).

The phenomenon of the "resource curse" is evident, where abundant natural resource wealth paradoxically leads to poor governance, lack of economic diversification, and social problems. The economy remains highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices. When oil prices fall, the country faces severe recessions, as seen in the period after 2014.

There is a critical need for economic diversification away from hydrocarbons to create sustainable development and employment. Investment in human capital through improved education and healthcare, strengthening governance, combating corruption, and implementing effective social programs to address the needs of vulnerable populations are major challenges. Equatorial Guinea attempted to become compliant with the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) to improve transparency in its resource revenues, obtaining candidate status in 2008, but did not complete validation by the deadline. The country is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA) and the Central African Monetary and Economic Union (CEMAC).

6.4. Other Sectors

While the oil and gas industry dominates Equatorial Guinea's economy, other sectors make smaller contributions and offer potential for diversification, though they have often been neglected.

- Agriculture**: Before the oil boom, agriculture, particularly the export of cocoa and coffee, was the mainstay of the economy. Today, agriculture is primarily for subsistence, with crops like cassava, plantains, sweet potatoes, and yams being important for local consumption. The production of traditional cash crops like cocoa and coffee has declined significantly from pre-independence levels. Agriculture provides employment for a significant portion of the rural workforce (around 52% of the total workforce and income for 57% of rural households, according to some estimates), but its contribution to GDP is small.

- Forestry**: Timber was historically an important export. Logging continues, but concerns about sustainable forest management and deforestation persist. The country has significant forest cover.

- Fishing**: Equatorial Guinea has coastal waters in the Gulf of Guinea with fishing potential, both for artisanal and commercial fishing. However, the sector is relatively underdeveloped compared to its potential.

- Services and Emerging Industries**: The services sector, including retail, telecommunications, and some financial services, has grown, partly driven by oil revenues and related activities. Tourism is minimal but has some potential given the country's natural landscapes and colonial architecture, though development is hampered by infrastructure limitations and political conditions. There have been efforts to develop infrastructure, such as ports and airports, which could support other industries if economic diversification becomes a priority.

Overall, these non-oil sectors are dwarfed by the hydrocarbon industry, and significant investment and policy focus would be needed to develop them into substantial contributors to a more diversified and equitable economy.

7. Transportation

Transportation infrastructure in Equatorial Guinea has seen some development, particularly since the oil boom, but challenges remain, especially in maintaining existing networks and ensuring accessibility across the country.

7.1. Road Network

Equatorial Guinea has approximately 1.8 K mile (2.88 K km) of highways. A significant portion of these roads were unpaved until the early 2000s. Since then, oil revenues have funded considerable road construction and improvement projects, particularly connecting major towns and cities. For example, a 175-km two-lane highway was built connecting Bata to President Obiang Nguema International Airport near Mongomeyen, with plans for extension to the Gabonese border. Main roads, especially in and around Malabo and Bata, are generally paved. However, in rural areas and during the rainy season, many secondary roads can become difficult to traverse without four-wheel-drive vehicles. Maintenance of the road network is an ongoing challenge. Public transport primarily consists of taxis and minibuses.

7.2. Air Transport

Equatorial Guinea has three main airports:

- Malabo International Airport (SSG)**: Located on Bioko Island, this is the country's primary international airport and serves as a hub for several airlines. It has direct connections to some European cities (e.g., Paris, Madrid) and major hubs in West and Central Africa.

- Bata Airport (BSG)**: Located in the mainland city of Bata, it serves domestic flights and some regional international connections.

- Annobón Airport**: A smaller airport serving Annobón Island.

- President Obiang Nguema International Airport**: A newer international airport built near Mengomeyén in the eastern part of Río Muni, intended to serve the planned new capital, Ciudad de la Paz.

National airlines have included CEIBA Intercontinental and Cronos Airlines. Historically, airlines registered in Equatorial Guinea have appeared on the list of air carriers banned from operating within the European Union due to safety concerns, though this status can change. Freight carriers also provide services, particularly to Malabo.

7.3. Maritime Transport

Equatorial Guinea relies heavily on maritime transport for international trade, especially for its oil and gas exports and the import of goods.

- Port of Malabo**: Located on Bioko Island, it is a major port handling general cargo, containers, and serving the offshore oil industry. It has undergone expansion and modernization.

- Port of Bata**: Situated on the mainland coast, Bata is the largest commercial port in terms of volume and serves as the primary gateway for Río Muni. It handles general cargo, timber exports, and other trade.

- Port of Luba**: Also on Bioko Island, south of Malabo, Luba has developed as a logistical base for the oil and gas industry, with a deepwater port.

There are also smaller port facilities and jetties along the coast. Passenger movement by sea is less common for international travel but occurs between the islands and the mainland.

8. Society

The society of Equatorial Guinea is shaped by its diverse ethnic composition, colonial history, the long-standing authoritarian rule, and the profound impact of oil wealth, which has exacerbated inequalities.

8.1. Population

| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 0.2 |

| 2000 | 0.6 |

| 2020 | 1.4 |

As of 2024, the population of Equatorial Guinea was estimated to be around 1.7 to 1.8 million people. The country has experienced significant population growth, partly due to high fertility rates and immigration related to the oil industry. Population density varies, with higher concentrations on Bioko Island (especially in Malabo) and in urban centers on the mainland like Bata, compared to more sparsely populated rural areas.

Key demographic indicators reflect the challenges despite oil wealth:

- Life expectancy** remains relatively low compared to global averages, though figures vary by source.

8.2. Ethnic Groups

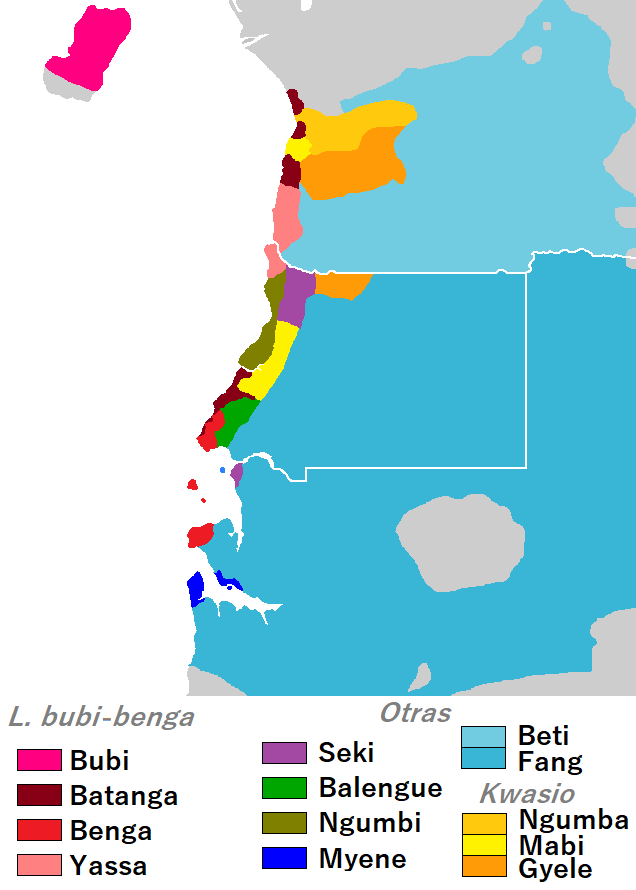

The majority of the people of Equatorial Guinea are of Bantu origin. The main ethnic groups include:

- Fang**: The largest ethnic group, constituting around 80-85% of the population. They are indigenous to the mainland (Río Muni) but significant migration to Bioko Island since the 20th century means they now also form a majority or large plurality there. The Fang are traditionally agriculturalists and are divided into numerous clans. Those in northern Río Muni speak Fang-Ntumu, while those in the south speak Fang-Okah; these dialects are mutually intelligible. Fang dialects are also spoken in parts of neighboring Cameroon and Gabon. President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo is of Fang ethnicity, and this group has dominated the country's political life.

- Bubi**: The second-largest group, making up about 6.5% to 15% of the population (estimates vary). They are the indigenous inhabitants of Bioko Island. Historically, the Bubi have had a distinct cultural and political identity and have sometimes experienced marginalization and repression, particularly under the Macías Nguema regime and to some extent under Obiang.

- Ndowe** (Playeros or "Beach People"): This is a collective term for several smaller coastal ethnic groups found on the mainland and smaller islands, including the Combes, Bujebas, Balengues, and Bengas. Together, they constitute around 5% of the population.

- Annobonese**: The inhabitants of Annobón Island, of mixed African (likely Angolan origin via Portuguese introduction) and European ancestry, speaking a Portuguese-based creole language.

- Fernandinos**: A Krio-speaking community on Bioko Island, descended from freed slaves and settlers from Sierra Leone and other parts of West Africa and the Caribbean during the 19th century.

- Other groups**: There are smaller communities of Europeans (largely of Spanish or Portuguese descent, some with partial African ancestry), though most ethnic Spaniards left after independence. A growing number of immigrants from neighboring Cameroon, Nigeria, and Gabon have come to the country, particularly since the oil boom. The Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations (2002) noted that 7% of Bioko islanders were Igbo from Nigeria. Asian communities, mostly Chinese and a small number of Indians, are also present.

Inter-ethnic relations have at times been strained, particularly concerning the political dominance of the Fang and the historical grievances of groups like the Bubi. The government's policies and resource allocation can sometimes be perceived through an ethnic lens, though overt ethnic conflict has not been a defining feature of recent decades in the way political repression has.

8.3. Languages

Equatorial Guinea has a unique linguistic landscape in Africa, with Spanish as its primary official and most widely spoken language.

- Spanish**: The main official language, a legacy of colonial rule. It is the language of government, education, business, and media, and serves as a lingua franca among the diverse ethnic groups. The local variant is known as Equatoguinean Spanish. According to the Instituto Cervantes, around 87.7% of the population has a good command of Spanish. Spanish has been an official language since 1844.

- French**: Adopted as the second official language in 1998, primarily to facilitate Equatorial Guinea's integration into regional economic blocs like CEMAC (Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa), whose founding members are French-speaking nations (two of which, Cameroon and Gabon, border Equatorial Guinea). French is not widely spoken locally, except in some border towns.

- Portuguese**: Adopted as the third official language in 2010. This move was largely driven by the government's desire to join the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), which it did in 2014. Like French, Portuguese is not widely spoken by the general population, though the Annobonese Creole (Fa d'Ambô) spoken on Annobón Island has Portuguese roots. Portuguese is also used as a liturgical language by some local Catholics.

- Indigenous Languages**: Aboriginal languages are recognized by the constitution as integral parts of the "national culture." These include:

Most African ethnic groups in Equatorial Guinea speak Bantu languages. The multilingual environment means many Equatoguineans are bilingual or trilingual, often speaking an indigenous language, Spanish, and sometimes Pichinglis or having some exposure to French.

8.4. Religion

The predominant religion in Equatorial Guinea is Christianity, adhered to by approximately 93% of the population.

- Roman Catholicism** is the largest Christian denomination, accounting for about 88% of the population. The Catholic Church has a long history in the country, dating back to the colonial era, and plays a significant role in social life and, to some extent, education.

- Protestant** denominations make up a smaller portion, around 5% of the population.

- Islam** is practiced by about 2% of the population, primarily Sunni Muslims, many of whom are immigrants from West African countries.

Freedom of religion is constitutionally guaranteed, but the government has at times placed restrictions on religious groups, particularly those perceived as critical of the regime. The relationship between the state and religious institutions, especially the Catholic Church, can be complex.

8.5. Education

Equatorial Guinea has made some strides in education since independence, particularly in increasing literacy rates, but significant challenges remain regarding access, quality, and equity, especially given the nation's oil wealth.

The literacy rate is relatively high for Sub-Saharan Africa; as of 2015, estimates suggested that 95.3% of the population aged 15 and over could read and write. This marks a significant improvement from the period under Francisco Macías Nguema, when education was severely neglected and illiteracy was rampant (around 73%). Under President Obiang, primary school enrollment reportedly rose from 65,000 in 1986 to over 100,000 by 1994. Education is officially free and compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 14.

The education system is structured into primary, secondary, and higher education levels.

- Primary Education**: Focuses on basic literacy and numeracy.

- Secondary Education**: Builds upon primary education, preparing students for higher education or vocational training.

- Higher Education**: The primary institution is the Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial (UNGE), established in 1995, with its main campus in Malabo and a Faculty of Medicine in Bata. The Bata Medical School has received support from Cuba, including Cuban medical educators. Spain's National University of Distance Education (UNED) also has branches in Malabo and Bata.

Despite official policies, the education sector faces numerous challenges:

- Quality of Education**: Shortages of qualified teachers, inadequate teaching materials, and overcrowded classrooms in some areas affect the quality of instruction.

- Access and Equity**: Disparities in access to education exist between urban and rural areas, and between different socio-economic groups. While primary enrollment may be high, dropout rates can be significant, particularly at the secondary level. Girls' education, while promoted, can face cultural and economic barriers.

- Funding and Resources**: Although the country has substantial oil revenue, investment in the education sector has often been criticized as insufficient or inefficiently managed.

- Curriculum**: The curriculum is largely based on the Spanish system. There have been efforts to adapt it to national needs, but relevance and modernization remain ongoing tasks.

The government has partnered with international organizations and corporations (e.g., Hess Corporation and the Academy for Educational Development - AED) on initiatives to improve teacher training and educational techniques, such as establishing model schools. However, systemic reforms and sustained investment are needed to ensure that the education system can effectively contribute to human capital development and provide equitable opportunities for all Equatoguineans.

8.6. Health

Despite significant oil wealth, Equatorial Guinea's public health indicators are generally poor, and access to quality healthcare is limited for much of the population, reflecting deep social inequalities.

Key public health issues and indicators include:

- Prevalent Diseases**: Malaria is a major public health problem and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially among children. Other infectious diseases common in tropical regions, such as respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, and HIV/AIDS, are also concerns. Tuberculosis is also present. Historically, polio was an issue, with an outbreak reported as recently as 2014.

- Maternal and Child Health**: Maternal and child mortality rates remain high for a country with Equatorial Guinea's per capita income. For example, in the early 2020s, the under-five mortality rate was reported at 7.9% (79 deaths per 1,000 live births). Limited access to prenatal care, skilled birth attendants, and postnatal care contributes to these poor outcomes.

- Healthcare Infrastructure**: While there has been some investment in constructing hospitals and clinics, particularly in urban areas like Malabo and Bata, the overall healthcare infrastructure is inadequate. Rural areas often lack accessible health facilities and trained medical personnel. Equipment and medical supplies can be scarce or outdated.

- Access to Medical Services**: Access to healthcare is often determined by socio-economic status and geographic location. Many citizens struggle to afford medical care, and the quality of public health services is often low. The elite frequently seek medical treatment abroad.

- Sanitation and Water**: Less than half the population has access to clean drinking water and improved sanitation facilities, contributing to the prevalence of waterborne diseases.

- Public Health Initiatives**: The government has undertaken some public health programs, occasionally with international support. For instance, malaria control programs involving indoor residual spraying (IRS), artemisinin combination treatments (ACTs), intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women (IPTp), and the distribution of long-lasting insecticide-treated mosquito nets (LLINs) reportedly achieved some success in reducing malaria infection and mortality in the early 21st century. However, sustained funding and comprehensive implementation of such programs are crucial.

Disparities in health outcomes and access to care are stark, with vulnerable populations, including those in rural areas and the urban poor, disproportionately affected. The significant oil revenues have not translated into a robust and equitable public health system for all citizens.

9. Culture

Equatorial Guinea's culture is a blend of indigenous traditions from its various ethnic groups, primarily Bantu-speaking, and the strong influence of Spanish colonialism. The long period of isolation under Macías Nguema, followed by the oil boom and increased international contact under Obiang, has also shaped contemporary cultural expressions.

In June 1984, the First Hispanic-African Cultural Congress was convened to explore and affirm the cultural identity of Equatorial Guinea, highlighting the interplay between its African heritage and Hispanic linguistic and cultural ties.

9.1. Media and Communications

The media landscape in Equatorial Guinea is heavily controlled by the state, with severe restrictions on freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

- Broadcast Media**: The principal means of communication are three state-operated FM radio stations. International broadcasters like the BBC World Service, Radio France Internationale, and Gabon-based Africa No 1 also broadcast on FM in Malabo. Televisión de Guinea Ecuatorial (RTVGE) is the state-operated television network and is the primary source of televised news and entertainment. Its international service, RTVGE Internacional, is available via satellite in Africa, Europe, and the Americas, and worldwide via the internet. Most broadcast media practice self-censorship and rarely criticize the government or public figures.

- Print Media**: There are few newspapers and magazines, and those that exist are often state-influenced or exercise caution in their reporting.

- Independent Media**: The presence of independent media is extremely limited. Reporters Without Borders consistently ranks Equatorial Guinea very low in its press freedom index, noting that the national broadcaster often obeys orders from the information ministry and that most media companies are under the directorship of the president's son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, or other close associates. A web-based radio and news source, Radio Macuto, known for its critical reporting on the Obiang regime, operates from outside the country.

- Telecommunications**: Landline telephone penetration is low, with only about two lines per 100 people in the past. Mobile telephone services are more widespread, with operators like Orange S.A. (formerly GETESA, in partnership with France Télécom) providing coverage, especially in Malabo, Bata, and other mainland cities. As of 2009, approximately 40% of the population subscribed to mobile telephone services.

- Internet**: Internet access has been growing, with over a million users reported by the World Bank by 2022. However, access can be expensive, and the government has been known to restrict access to social media or critical websites, particularly during times of political sensitivity.

The overall media environment significantly limits access to diverse and independent information for the citizens of Equatorial Guinea, reinforcing state narratives and curtailing public discourse.

9.2. Literature

Equatoguinean literature is primarily written in Spanish, making it unique in Sub-Saharan Africa. Its development has been influenced by both indigenous oral traditions and Spanish literary models, as well as the country's tumultuous political history. Key themes often include colonialism, identity, exile, social critique, and the experiences under dictatorial regimes.

Prominent writers often emerged from exile due to political repression. Some notable figures include:

- Juan Balboa Boneke**: A poet and politician.

- María Nsué Angüe**: Considered one of the most important female writers, known for her novel Ekomo.

- Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo**: A novelist, journalist, and historian, whose works often explore historical and contemporary issues.

- Raquel Ilonbé**: A poet.

- Trifonia Melibea Obono**: A contemporary writer known for addressing themes such as gender, sexuality, and tradition.

The context for literary expression within Equatorial Guinea itself has been challenging due to censorship and lack of publishing opportunities. Many works are published abroad, particularly in Spain. The documentary The Writer from a Country Without Bookstores highlights the difficulties faced by writers and intellectuals in the country.

9.3. Music

The music of Equatorial Guinea incorporates indigenous folk traditions, Spanish influences, and contemporary African popular music.

- Traditional Music**: Ethnic groups like the Fang, Bubi, and Combe have their own traditional musical forms, often featuring drums, xylophones, and vocal harmonies, used in ceremonies, storytelling, and social events. The balélé dance is a well-known traditional form.

- Popular Music**: Pan-African styles such as soukous and makossa from neighboring Congo and Cameroon are popular. Reggae, Latin trap, and rock and roll also have a following. Local artists blend these influences with indigenous rhythms.

- Spanish Influence**: Spanish musical styles, including flamenco and folk music, have had some impact, particularly in older generations or formal settings.

- Notable Artists**: While international recognition is limited, artists like Hijas del Sol (a Bubi duo who gained popularity in Spain) have brought Equatoguinean sounds to a wider audience.

Music plays an important role in social gatherings, celebrations, and cultural expression.

9.4. Cuisine

The cuisine of Equatorial Guinea is based on local staples and reflects both indigenous traditions and influences from Spanish colonial rule and trade with neighboring countries. Common ingredients include:

- Starchy Staples**: Cassava (yuca), plantains (both green and ripe), yams, and taro are fundamental. These are often boiled, fried, or pounded into a fufulike consistency.

- Proteins**: Fish and seafood are abundant along the coast and on the islands. Chicken is also common. Bushmeat (game) is consumed in some areas, though this raises conservation concerns.

- Vegetables and Fruits**: Okra, spinach, eggplant, tomatoes, and peppers are used. A variety of tropical fruits like mangoes, pineapples, bananas, and papayas are available.

- Sauces and Spices**: Dishes are often prepared with sauces made from peanuts (groundnut sauce), palm oil, or local greens. Spices like chili peppers, ginger, and garlic are used for flavoring.

Some typical dishes include:

- Pepe soup**: A spicy fish or meat soup.

- Groundnut soup/stew**: Meat or fish cooked in a rich peanut sauce.

- Bilolá**: A dish made with snails.

Palm wine is a common traditional beverage.

9.5. Sports

Football (soccer) is the most popular sport in Equatorial Guinea.

- National Teams**: The men's national team (Nzalang Nacional) and the women's national team have achieved some notable successes.

- The women's team won the African Women's Championship in 2008 (as hosts) and 2012, and qualified for the 2011 FIFA Women's World Cup in Germany.

- The men's team co-hosted the 2012 Africa Cup of Nations with Gabon, reaching the quarter-finals. They also hosted the 2015 edition on short notice and achieved a fourth-place finish, their best performance to date.

- Domestic League**: The country has a domestic football league, the Equatoguinean Primera División.

- Other Sports**: Basketball has been increasing in popularity. Equatorial Guinea has also participated in the Olympic Games since the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, though it has not yet won any medals. Swimmers Eric Moussambani ("Eric the Eel") and Paula Barila Bolopa ("Paula the Crawler") gained international fame for their perseverance despite slow times at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

- Hosting Events**: Besides the Africa Cup of Nations, Equatorial Guinea was chosen to host the 12th African Games in 2019 (though this was later moved).

Investment in sports infrastructure, particularly football stadiums, has occurred, often linked to hosting international tournaments.

9.6. Tourism

Tourism in Equatorial Guinea is relatively undeveloped but holds some potential due to its natural attractions and colonial heritage.

- Main Tourist Attractions**:

- Bioko Island**: Offers diverse landscapes, from volcanic peaks like Pico Basilé to beaches. The southern part of the island is known for hiking opportunities to waterfalls like the Iladyi cascades and remote beaches where sea turtles nest. The colonial architecture in Malabo is also an attraction. The resort area of Sipopo, near Malabo, was developed with luxury hotels and conference facilities.

- Río Muni (Mainland)**: Features lush rainforests, national parks like Monte Alén National Park, and diverse wildlife. The city of Bata has a shoreline promenade (Paseo Marítimo) and the Torre de la Libertad (Freedom Tower).

- Mongomo**: Known for the large Basilica of the Immaculate Conception, one of the largest Catholic churches in Africa.

- Ciudad de la Paz**: The planned new capital, with modern architecture emerging from the rainforest, presents a unique, if controversial, point of interest.

- Annobón Island**: A remote volcanic island with a unique culture and natural beauty, though difficult to access.

- Current State and Potential**: The tourism industry is still in its nascent stages. Challenges include limited infrastructure outside major urban areas, visa restrictions, high costs, and the country's political image. As of 2020, Equatorial Guinea had no UNESCO World Heritage Sites or sites on the tentative list, nor any heritage documented in UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme or Intangible Cultural Heritage List.

- Sustainability and Community Impact**: Future tourism development would need to consider aspects of environmental sustainability and ensure benefits reach local communities, which has been a challenge in other sectors dominated by centralized state control.

The government has expressed interest in developing tourism, particularly focusing on high-end and conference tourism, but significant investment in marketing, infrastructure, and human resources, along with improvements in governance and accessibility, would be required for the sector to flourish.

9.7. Public Holidays

Equatorial Guinea observes a number of national and public holidays, which include both secular and religious celebrations. Major public holidays include:

- January 1**: New Year's Day (Año Nuevo)

- May 1**: Labour Day (Día del Trabajo)

- June 5**: President's Day / Birthday of the President (Natalicio del Presidente de la República) - Celebrating Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo's birthday.

- August 3**: Freedom Day / Armed Forces Day (Día del Golpe de Libertad) - Commemorates the 1979 coup that brought President Obiang to power.

- August 15**: Constitution Day (Día de la Constitución)

- October 12**: Independence Day (Día de la Independencia) - Celebrates independence from Spain in 1968.