1. Early Life and Education

Jascha Heifetz's early life was marked by his prodigious musical talent, which was nurtured from a very young age in his native Lithuania.

1.1. Birth and Childhood

Heifetz was born into a Lithuanian-Jewish family in Vilnius, which was then part of the Russian Empire and is currently the capital of Lithuania. While his birth year is widely cited as 1901, some sources suggest he may have been born a year or two earlier, in 1899 or 1900. It has been speculated that his mother might have intentionally stated he was younger to enhance the perception of his extraordinary abilities. His father, Reuven Heifetz, was a local violin teacher and served as the concertmaster of the Vilnius Theatre Orchestra for one season before the theater closed. Early on, Reuven conducted a series of tests, observing his infant son's reactions to his violin playing. Convinced of Jascha's immense potential, his father acquired a small violin for him before he turned two and began teaching him basic bowing techniques and simple fingering.

1.2. Early Musical Training

At the age of three, Jascha Heifetz first picked up the violin. He began formal music lessons with Elias Malkin (also known as Ilya Malkin) at either age four or five at the local music school in Vilna. As a recognized child prodigy, he made his public debut at the age of seven in Kovno (now Kaunas, Lithuania), performing the Violin Concerto in E minor by Felix Mendelssohn. In 1910, he enrolled in the Saint Petersburg Conservatory to study violin under Ionnes Nalbandian, and later with the renowned Leopold Auer, a pivotal figure in Russian violin pedagogy. Auer would later document his teaching philosophy in his 1920 book, Violin Playing as I Teach It.

2. Early Career

Heifetz's early career saw his rapid ascent from a child prodigy to an internationally acclaimed violinist, culminating in a sensational American debut that cemented his reputation.

2.1. European Tours and Early Recognition

While still in his teens, Heifetz extensively toured much of Europe. In April 1911, he performed in an outdoor concert in St. Petersburg, drawing an audience of 25,000 spectators. The reaction was so overwhelming that police officers were required to protect the young violinist after the performance. He made his Berlin debut at the age of 12, invited by Arthur Nikisch. In May 1912, Heifetz met fellow violinist Fritz Kreisler for the first time at a private press matinee held at the Berlin home of Arthur Abell, a prominent music critic for the American magazine Musical Courier. After the 12-year-old Heifetz performed the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, Abell reported that Kreisler famously remarked to all present, "We may as well break our fiddles across our knees." In 1914, Heifetz performed with the Berlin Philharmonic under the baton of Arthur Nikisch, who expressed profound admiration, stating he had never heard such an excellent violinist.

2.2. American Debut and Establishment of Reputation

To escape the escalating violence of the Russian Revolution, Heifetz and his family departed Russia in 1917, traveling by rail through the Russian Far East and then by ship to the United States, arriving in San Francisco. On October 27, 1917, Heifetz made his highly anticipated American debut at Carnegie Hall in New York City, creating an immediate sensation.

In the audience, fellow violinist Mischa Elman quipped, "Do you think it's hot in here?" to which the pianist Leopold Godowsky, seated nearby, famously replied, "Not for pianists." In the same year, at just 16, Heifetz was elected an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, the national fraternity for men in music, making him one of the youngest individuals ever admitted to the organization. Heifetz decided to remain in the United States, becoming a naturalized citizen in 1925. A well-known anecdote recounts an exchange with one of the Marx Brothers (often attributed to Groucho Marx or Harpo Marx): when Heifetz mentioned he had been earning his living as a musician since the age of seven, he received the retort, "Before that, I suppose, you were just a bum." By the age of 18, Heifetz had already become the highest-paid violinist in the world. On April 17, 1926, he performed at Ein Harod, which was then a central location for the Mandatory Palestine's kibbutz movement.

In 1954, Heifetz began a long collaboration with pianist Brooks Smith, who served as his accompanist for many years until Heifetz's retirement, when Ayke Agus took over. He was also accompanied in concert for more than two decades by Emanuel Bay, another Russian immigrant and a close personal friend. Heifetz possessed such profound musicianship that he would often demonstrate to his accompanists how he desired passages to sound on the piano, even suggesting specific fingerings. After the 1955-56 concert seasons, Heifetz announced a significant reduction in his concert activity, stating, "I have been playing for a very long time." In 1958, he suffered a fall in his kitchen, fracturing his right hip. This incident led to hospitalization at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital and a nearly fatal Staphylococcus infection. Despite this, he was invited to perform Beethoven at the United Nations General Assembly and made his appearance leaning on a cane. By 1967, Heifetz had considerably curtailed his public concert performances.

3. Musical Technique and Interpretation

Jascha Heifetz was renowned for his distinctive violin playing, characterized by an unparalleled technical mastery and a deeply expressive interpretative approach across various musical genres.

3.1. Technique and Timbre

Lois Timnick of the Los Angeles Times described Heifetz as being "regarded as the greatest violin virtuoso since Niccolò Paganini." Music critic Harold Schonberg of The New York Times wrote that Heifetz "set all standards for 20th-century violin playing... everything about him conspired to create a sense of awe." Violinist Itzhak Perlman acknowledged Heifetz's enduring influence, stating, "The goals he set still remain, and for violinists today it's rather depressing that they may never really be attained again."

Despite initial criticisms from some, such as Virgil Thomson's characterization of his playing as "silk underwear music"-a phrase not intended as a compliment-other critics argued that Heifetz profoundly infused his playing with both deep feeling and a reverence for the composer's intentions. His unique playing style was highly influential in shaping the approach of modern violinists. Heifetz's use of a rapid vibrato, emotionally charged portamento, fast tempi, and superb bow control coalesced to produce a highly distinctive sound that made his playing instantly recognizable to aficionados. Itzhak Perlman, himself noted for his rich, warm tone and expressive use of portamento, vividly described Heifetz's tone as being like "a tornado" due to its sheer emotional intensity. Perlman also noted that Heifetz preferred to record relatively close to the microphone, which meant that a slightly different tone quality might be perceived when listening to him in a concert hall performance compared to his recordings.

Heifetz was extremely particular about his choice of strings. He consistently used a silver-wound Tricolore gut G string, plain unvarnished gut D and A strings, and a Goldbrokat medium steel E string. He applied clear Hill-brand rosin sparingly. Heifetz firmly believed that playing on gut strings was crucial for achieving an individual and unique sound. His bowing technique, rooted in the Auer (Russian) school, involved placing the right index finger deep on the bow beyond the PIP joint. He was known for his swift bow speed, relaxed grip, and meticulously precise bow changes, which were consistent in velocity. He was also a master of intricate techniques like down-staccato. His extraordinary virtuosity in left-hand positioning and fingering could be visually observed in his performance of Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto (first movement, abridged) in the film Carnegie Hall.

3.2. Repertoire and Interpretation

Heifetz's vast performing repertoire spanned numerous genres, from intimate short pieces and chamber music to grand concertos, all performed with his characteristic technical brilliance and interpretive depth.

3.2.1. Short Pieces and Chamber Music

The genre of short pieces was often considered Heifetz's true essence, showcasing his mastery. He recorded an exceptionally wide array of works from various periods and nationalities, skillfully differentiating the character of each piece. For example, he could evoke a majestic world in Vitali's Chaconne while effortlessly delivering the challenging Hora staccato by Grigoraș Dinicu, captivating audiences.

His most renowned chamber music activities involved the "Million Dollar Trio," a collaboration with cellist Emanuel Feuermann and pianist Arthur Rubinstein. While Heifetz and Rubinstein, both established figures, frequently experienced personality clashes and differing opinions despite their artistic successes, Heifetz cultivated an exceptionally strong relationship with Feuermann. Feuermann's premature death profoundly affected Heifetz, leading him to significantly curtail his enthusiasm for chamber music recordings. Following Feuermann's passing, Gregor Piatigorsky joined Heifetz and Rubinstein for later collaborations, with the trio recording works by Maurice Ravel, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and Felix Mendelssohn. Heifetz also recorded several string quintets with violinist Israel Baker, violists William Primrose and Virginia Majewski, and Piatigorsky. Among his solo works, his rendition of Richard Strauss's Violin Sonata became particularly notable due to the controversy it sparked during his 1953 tour of Israel.

3.2.2. Concertos

Heifetz extensively recorded numerous violin concertos, including those by Johann Sebastian Bach, as well as the widely recognized "Three Great Concertos" by Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. His repertoire also included concertos by composers such as Henryk Wieniawski and Henri Vieuxtemps. He notably premiered Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Violin Concerto at a time when many classical musicians avoided Korngold's compositions due to his work scoring films for Warner Bros., believing it diminished his standing as a "serious" composer. Heifetz's performances of both the Korngold concerto and Max Bruch's Scottish Fantasy (which he helped popularize globally) are still considered definitive recordings.

Key recordings of concertos include:

- The Beethoven Violin Concerto in 1940 with the NBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Arturo Toscanini, and again in stereo in 1955 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Charles Munch. A live, unofficial release exists of his April 9, 1944, NBC radio broadcast performance of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with Toscanini and the NBC Symphony.

- The Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in 1957 with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

- The Brahms Violin Concerto in 1955 with Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

- The Sibelius Violin Concerto in 1959 with Walter Hendl and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

- Alexander Glazunov's A minor Concerto in 1963 with Walter Hendl and the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra.

- Sergei Prokofiev's Violin Concerto No. 2 in 1959 with Charles Munch.

- The Brahms Concerto for Violin and Cello in 1960 with Gregor Piatigorsky (cello) and the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alfred Wallenstein.

- Bach's Concerto for Two Violins in 1961 with Erick Friedman and Sir Malcolm Sargent. He also produced a rare 1946 multi-track recording of this piece in Hollywood, where he played both violin parts himself, with accompaniment by the RCA Victor Chamber Orchestra conducted by Franz Waxman.

- Mozart's Violin Concerto No. 4 in 1961 with Sir Malcolm Sargent, and Violin Concerto No. 5 "Turkish" in 1963, which Heifetz conducted himself with a chamber orchestra.

Heifetz was approached by Arnold Schoenberg to premiere his Violin Concerto but declined, famously remarking that it "needed six fingers." He later expressed regret for this decision in his memoirs. Despite his exceptional technical prowess, Heifetz recorded relatively few works by Niccolò Paganini, a fact for which he never publicly stated a clear reason. Exceptions include recordings of Paganini's Caprices No. 13, 20, and 24, as arranged by Leopold Auer, and his youthful recording of Moto perpetuo.

4. Recording Career

Jascha Heifetz maintained an extensive recording career throughout his life, collaborating with major record labels and leaving behind a vast discography that showcases his unparalleled artistry.

4.1. Early Recordings

Heifetz made his very first recordings in Russia between 1910 and 1911 while still a student of Leopold Auer. The existence of these early recordings was not widely known until after his death, when several sides, including François Schubert's L'Abeille (The Bee), were reissued on an LP album that was included as a supplement to The Strad magazine. Shortly after his sensational Carnegie Hall debut, on November 9, 1917, Heifetz made his first recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company/RCA Victor, a label with which he remained for the majority of his distinguished career. On October 28, 1927, Heifetz was the starring act at the grand opening of Tucson, Arizona's now-historic Temple of Music and Art.

4.2. Collaborations with Major Record Labels

For several years in the 1930s, Heifetz primarily recorded for HMV/EMI in the United Kingdom. This shift occurred because RCA Victor had reduced its investment in expensive classical recording sessions during the Great Depression. These HMV discs were subsequently issued in the United States by RCA Victor.

Heifetz often enjoyed performing chamber music, though some critics suggested that his formidable artistic personality tended to overshadow his colleagues. His notable collaborations include his 1941 recordings of piano trios by Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms with cellist Emanuel Feuermann and pianist Arthur Rubinstein. A later collaboration saw him join Rubinstein and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky to record trios by Maurice Ravel, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, and Felix Mendelssohn. Both of these formations were colloquially referred to as the Million Dollar Trio. Heifetz also recorded several string quintets with violinist Israel Baker, violists William Primrose and Virginia Majewski, and Piatigorsky. He famously recorded Erich Wolfgang Korngold's Violin Concerto, a bold choice at a time when many classical musicians avoided Korngold's works due to his film scoring activities, which led some to question his standing as a "serious" composer.

4.3. Wartime and Later Recordings

From 1944 to 1946, Heifetz recorded with American Decca due to the American Federation of Musicians recording ban, which began in 1942. Decca had settled its dispute with the union in 1943, well before RCA Victor resolved theirs. During this period, Heifetz primarily recorded short pieces, including his own arrangements of music by George Gershwin and Stephen Foster; these were often performed as encores in his recitals. He was accompanied on the piano by Emanuel Bay or Milton Kaye. Among his more unusual discs was a collaboration with Decca's popular artist, Bing Crosby, on "Lullaby" from Benjamin Godard's opera Jocelyn and Where My Caravan Has Rested by Hermann Löhr, with Decca's studio orchestra conducted by Victor Young. Heifetz soon returned to RCA Victor, where he continued to make extensive recordings until the early 1970s.

His later recordings for RCA Victor, beginning in 1946, included numerous solo, chamber, and concerto performances, often with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Charles Munch and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Fritz Reiner. In 2000, RCA released Jascha Heifetz - The Supreme, a double CD compilation showcasing a selection of his major recordings. This compilation featured his 1955 recording of Brahms's Violin Concerto with Reiner and the Chicago Symphony; the 1957 Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto with the same forces; the 1959 Sibelius Violin Concerto with Walter Hendl and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra; the 1961 Max Bruch's Scottish Fantasy with Sir Malcolm Sargent and the New Symphony Orchestra of London; the 1963 Glazunov's A minor Concerto with Walter Hendl and the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra; the 1965 George Gershwin's Three Preludes (transcribed by Heifetz) with pianist Brooks Smith; and the 1970 Bach's unaccompanied Chaconne from the Partita No. 2 in D minor.

5. Major Activities and Tours

Heifetz's career was marked by significant performances and extensive international tours, some of which became notable for controversial incidents highlighting his strong convictions.

5.1. Wartime Service and Performances

During World War II, Heifetz actively contributed to the war effort. He commissioned several new pieces, including the Violin Concerto by Sir William Walton. He also arranged a number of existing works, such as Hora staccato by the Romanian gypsy composer Grigoraș Dinicu, whom Heifetz was rumored to have called the greatest violinist he had ever heard. Beyond his violin performances, Heifetz also played and composed for the piano. He performed "mess hall jazz" for Allied soldiers at camps across Europe under the auspices of the United Service Organizations (USO). Furthermore, using the alias Jim Hoyl, he composed a hit song titled "When You Make Love to Me (Don't Make Believe)," which was famously sung by Bing Crosby. In May 1945, Heifetz even performed with his son for distinguished military leaders Ivan Konev and Omar Bradley in Kassel, Germany.

5.2. International Tours and Controversies

Heifetz toured extensively throughout his career, but some of his international performances drew considerable attention due to social or political sensitivities.

5.2.1. Third Israel Tour and Richard Strauss Sonata Controversy

On his third concert tour to Israel in 1953, Heifetz chose to include the Violin Sonata by Richard Strauss in his recitals. At that time, many Israelis considered Strauss and a number of other German intellectuals to be Nazis or Nazi sympathizers, leading to an unofficial ban on their works in Israel, alongside those of Richard Wagner. This sensitivity was heightened by the fact that the Holocaust had occurred less than ten years prior. Despite a last-minute plea from Ben-Zion Dinur, the Israeli Minister of Education, a defiant Heifetz firmly stated, "The music is above these factors... I will not change my program. I have the right to decide on my repertoire." His performance of the Strauss sonata in Haifa was met with applause, but in Tel Aviv, it was followed by a chilling dead silence.

Following his recital in Jerusalem, Heifetz was physically attacked outside his hotel by a young man who struck his violin case with a crowbar. Heifetz instinctively used his bow-controlling right hand to protect his priceless violins. The attacker escaped and was never identified, though the incident has since been attributed to the Kingdom of Israel militant group. The attack made international headlines, and Heifetz defiantly announced that he would not cease playing the Strauss piece. However, threats persisted, and he ultimately omitted the Strauss sonata from his subsequent recital without explanation. His final concert on that tour was canceled after his swollen right hand began to cause him pain. Heifetz subsequently left Israel and did not return until 1970. Despite the controversy, he continued to perform the Strauss sonata, even including it in his farewell concert in 1972.

5.2.2. Visits to Japan

Jascha Heifetz had a unique connection with Japan, making several visits throughout his career. His first stop in Japan occurred in 1917, where he stayed for about two weeks while en route to the United States. He was scheduled to perform in Japan in September 1923, but during his voyage, he learned that Tokyo had been devastated by the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Upon hearing the news, Heifetz organized an impromptu concert on board his ship, raising 3.00 K JPY as a donation for the relief efforts. Although the September performances were postponed, he eventually arrived in November 1923, performing for three days at the Imperial Hotel. The day after, he held an outdoor benefit concert at Hibiya Park, collecting another 3.00 K JPY for earthquake relief. For his contributions, he was hailed as the "Benefactor of Imperial Capital's Restoration." Heifetz returned to Japan in 1931, performing from September to November at venues such as the Kabuki-za. His last concert tour to Japan took place in April 1954.

6. Personal Life

Beyond his demanding musical career, Jascha Heifetz's personal life included two marriages and a range of hobbies and interests that offered him respite from the stage.

6.1. Marriages and Family

Heifetz was married twice, with each marriage lasting approximately 17 years. His first wife was Florence Vidor, a silent film actress and the ex-wife of film director King Vidor. They married in August 1928, with Florence being 33 and Heifetz 27. Their union, between a Christian from Texas and a Russian Jew, drew comment from the Jewish media. Florence brought her nine-year-old daughter, Suzanne Vidor, into the marriage. With Florence, Heifetz had two children: a daughter, Josefa Heifetz, born in 1930, and a son, Robert Joseph Heifetz, born in 1932. Heifetz filed for divorce from Florence in late 1945 in Santa Ana, California.

His second marriage was to Frances Spiegelberg (1911-2000) in January 1947 in Beverly Hills. Frances was a New York society lady who also had a previous marriage and two children. Their son, Joseph "Jay" Heifetz, was born in September 1948 in Los Angeles. Heifetz divorced Frances in 1963, with temporary alimony ordered by the court in January and the divorce finalized in December of that year.

6.2. Hobbies and Interests

Outside of his intensive musical commitments, Heifetz pursued several hobbies and interests. He greatly enjoyed sailing off the coast of Southern California. He was also an avid stamp collector. For physical recreation, he played tennis and ping-pong. Intellectually, he maintained a personal library filled with books.

7. Later Life and Teaching Career

After retiring from active performance, Jascha Heifetz dedicated his later years to teaching and advocating for important social and environmental causes, leaving a lasting impact beyond the concert stage.

7.1. Retirement from Performance and Changes

Following a partially successful operation on his right shoulder in 1972, Heifetz made the decision to cease giving public concerts and making recordings. While his remarkable prowess as a performer remained evident, and he continued to play privately until the end of his life, the surgery had affected his bowing arm, preventing him from holding the bow as high as he once could. This physical limitation marked a significant change in his professional life, redirecting his energies toward other endeavors.

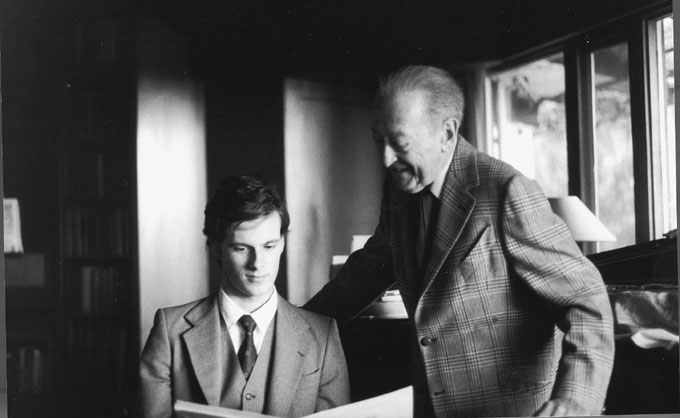

7.2. Dedication to Teaching

In his later life, Heifetz became widely recognized as a dedicated and influential teacher. He held prestigious master classes, initially at UCLA, and subsequently at the University of Southern California (USC). At USC, his faculty colleagues included the renowned cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and violist William Primrose. For a few years in the 1980s, Heifetz also conducted classes from his private studio at his home in Beverly Hills. His teaching studio, a source of inspiration for students, is now preserved and can be visited at the main building of the Colburn School in Los Angeles. During his extensive teaching career, Heifetz mentored numerous students who went on to achieve distinction, including Erick Friedman, Pierre Amoyal, Adam Han-Gorski, Rudolf Koelman, Endre Granat, Teiji Okubo, Eugene Fodor, Paul Rosenthal, Ilkka Talvi, Ayke Agus, and Simon Young Kim.

7.3. Social and Environmental Activism

Heifetz was also a passionate champion of various socio-political and environmental causes. He publicly advocated for the establishment of 9-1-1 as a universal emergency telephone number. Furthermore, he vigorously campaigned for clean air, actively protesting air pollution. In a notable demonstration of his commitment, he and his students at the University of Southern California protested smog by wearing gas masks. In 1967, demonstrating a pioneering spirit in environmentalism, Heifetz converted his Renault passenger car into an electric vehicle.

8. Death

Jascha Heifetz died at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, on December 10, 1987, at the age of 86. His death followed a fall in his home.

9. Legacy and Assessment

Jascha Heifetz left an indelible mark on the world of classical music, profoundly influencing violin playing, accumulating a collection of historically significant instruments, and earning widespread critical acclaim and enduring public perception.

9.1. Influence on Violin Playing

Heifetz is widely regarded as having a profound influence on 20th-century violin performance styles, setting new standards for the instrument. His impact on subsequent generations of violinists was so significant that Itzhak Perlman spoke of an "inferiority complex" or "Heifetz disease" that afflicted many of his contemporary violinists due to Heifetz's seemingly unattainable level of artistry.

While initially, during his lifetime, Heifetz faced some criticism for being a "cold violinist" who seemingly prioritized technical perfection over emotional expression, his musical depth and precision have been thoroughly re-evaluated and universally celebrated since his death. He is now firmly established as one of the definitive masters of the 20th century, often referred to as the "King of Violinists." Anecdotes from his early life further illustrate his extraordinary talent: it is said that as a young child, he would cry if his father played a note out of tune. Fritz Kreisler's famous remark after hearing the young Heifetz perform stands as a testament to his immediate and overwhelming genius. Beyond his musical attributes, Heifetz is also noted for his high intelligence and gifted intellect.

9.2. Owned Instruments and Memorials

Jascha Heifetz owned several historically important violins during his lifetime. Among them were the 1714 Dolphin Stradivarius, the 1731 "Piel" Stradivarius, the 1734 Stradivari, the 1736 Carlo Tononi, and the 1741 Guadagnini from Piacenza. The 1736 Carlo Tononi, which he used for his 1917 Carnegie Hall debut, was bequeathed in his will to his Master-Teaching Assistant, Sherry Kloss, along with "one of my four good bows." Kloss later co-founded the Jascha Heifetz Society and authored the book Jascha Heifetz Through My Eyes. The Dolphin Stradivarius is currently owned by the Nippon Music Foundation and is on loan to violinist Ray Chen.

Heifetz's most cherished instrument was the 1742 ex-David Guarneri del Gesù, which he preferred and kept until his death. This famed Guarneri is now housed at the San Francisco Legion of Honor Museum, as instructed by Heifetz's will, with the stipulation that it may only be taken out and played "on special occasions" by deserving violinists. It has recently been on loan to San Francisco Symphony's concertmaster Alexander Barantschik, who featured it in 2006 with Andrei Gorbatenko and the San Francisco Academy Orchestra. In 1989, Heifetz was posthumously awarded a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, a recognition of his enduring contribution to music.

9.3. Family Legacy

Heifetz's children and grandson have carried on his legacy in various fields. His first child, Josefa, is a distinguished lexicographer and the author of Dictionary of Unusual, Obscure and Preposterous Words; her married name is Josefa Heifetz Byrne. His second child, Robert Joseph Heifetz, inherited his father's love for sailing. He became an educator in urban planning at several colleges and universities and was a dedicated peace activist, protesting US military intervention worldwide and advocating for peace talks between Israel and Palestine. Robert Heifetz passed away from cancer in 2001.

Heifetz's third child, Joseph "Jay" Heifetz, pursued a career as a professional photographer. He held significant roles in the arts and entertainment industry, serving as the head of marketing for the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Hollywood Bowl, and as the chief financial officer of Paramount Pictures' Worldwide Video Division. He currently resides and works in Fremantle, Western Australia. Heifetz's grandson, Daniel Mark "Danny" Heifetz (born 1964), is a musician best known for his decade-long tenure as a drummer for the band Mr. Bungle from 1988 to 1999.

10. Filmography

Jascha Heifetz made notable appearances in films and television, bringing his musical artistry to a broader audience. He played a featured role in the 1939 film They Shall Have Music, directed by Archie Mayo and written by John Howard Lawson and Irmgard von Cube. In this movie, Heifetz played himself, stepping in to save a music school for underprivileged children from foreclosure, and his role included numerous performance scenes. He later appeared in the 1947 film Carnegie Hall, where he performed an abridged version of the first movement of Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto, with the orchestra led by Fritz Reiner. In 1951, Heifetz was featured in the film Of Men and Music. His teaching was captured in a televised series of his master classes in 1962. In 1971, Heifetz on Television aired as an hour-long color special, showcasing his performances of a series of short works, including Max Bruch's Scottish Fantasy and the Chaconne from Bach's Partita No. 2 in D minor, with Heifetz himself conducting the orchestra.