1. Overview

Amy Johnson was a pioneering English aviator who achieved international recognition as the first woman to fly solo from London to Australia. Throughout the 1930s, whether flying alone or with her husband, Jim Mollison, she set numerous long-distance flight records, cementing her status as a celebrated figure in aviation history. Her daring exploits inspired many, including the character portrayed by Katharine Hepburn in the 1933 film *Christopher Strong*. During the Second World War, Johnson contributed to the war effort as a pilot for the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), transporting aircraft across the country. Her life tragically ended on January 5, 1941, when her aircraft crashed into the Thames Estuary and she disappeared after bailing out. The exact circumstances of her death remain unknown, with theories ranging from drowning or hypothermia to being struck by a warship's propellers or even friendly fire, making her disappearance a subject of ongoing discussion.

2. Early life and Education

Amy Johnson's early life in Kingston upon Hull laid the foundation for her later groundbreaking career, which began with her education and early foray into aviation.

2.1. Childhood and Education

Born on July 1, 1903, in Kingston upon Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire, Amy Johnson was the eldest of three sisters, with Irene being a year younger. Her family was prominent in the area; her mother, Amy Hodge, was the granddaughter of William Hodge, a former Mayor of Hull, and her father, John William Johnson, was a fish merchant whose family owned the firm of Andrew Johnson, Knudtzon and Company. Johnson received her education at Boulevard Municipal Secondary School, which later became Kingston High School. She then attended the University of Sheffield, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics. After completing her studies, she moved to London, where she worked as a secretary for solicitor William Charles Crocker.

2.2. Entry into Aviation and License Acquisition

Johnson's interest in aviation began as a hobby, which quickly developed into a serious pursuit. She obtained her aviator's certificate, No. 8662, on January 28, 1929, followed by her pilot's "A" licence, No. 1979, on July 6, 1929. Both certifications were acquired at the London Aeroplane Club, where she received instruction from Captain Valentine Baker. In the same year, 1929, she further distinguished herself by becoming the first British woman to earn a ground engineer's "C" licence. Johnson also developed a close friendship and professional collaboration with Fred Slingsby, whose Yorkshire-based company, Slingsby Aviation of Kirbymoorside, North Yorkshire, grew to become the United Kingdom's most renowned glider manufacturer. Slingsby was instrumental in establishing the Yorkshire Gliding Club at Sutton Bank, and Johnson became an early member and trainee there during the 1930s, further honing her flying skills.

3. Aviation Career and Major Achievements

Amy Johnson's aviation career was marked by a series of pioneering flights and record-breaking achievements that captured global attention, often intertwined with her personal life.

3.1. England-Australia Solo Flight

In 1930, Amy Johnson achieved worldwide fame by becoming the first woman to fly solo from England to Australia. She secured the funds for her first aircraft from her father, who was a steadfast supporter of her ambitions, and from Lord Wakefield. With this support, she purchased a secondhand de Havilland DH.60 Gipsy Moth aircraft, registered G-AAAH, which she christened Jason in homage to her father's business trademark. On May 5, 1930, Johnson departed from Croydon Airport, Surrey, embarking on her historic journey. She successfully landed at Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia, on May 24, 1930, completing a distance of 11.00 K mile (11 K mile (18.00 K km)). Six days after her arrival, she sustained damage to her aircraft during a downwind landing at Brisbane airport. While Jason underwent repairs, she flew to Sydney with Captain Frank Follett. Subsequently, Captain Lester Brain flew the repaired Jason to Mascot, Sydney. Today, Jason is preserved and on permanent display in the Flight Gallery of the Science Museum, London.

In recognition of this monumental achievement, Johnson was awarded the prestigious Harmon Trophy and was appointed a Commander of the CBE in George V's 1930 Birthday Honours. Furthermore, she received the No. 1 civil pilot's licence under Australia's 1921 Air Navigation Regulations, a testament to her pioneering spirit.

3.2. Long-Distance Flight Records and Race Participation

Following her success in Australia, Johnson continued to pursue long-distance flight records. She acquired a de Havilland DH.80 Puss Moth registered G-AAZV, which she named Jason II. In July 1931, flying with co-pilot Jack Humphreys, she became part of the first team to complete a flight from London to Moscow in a single day, covering a journey of 1.76 K mile in approximately 21 hours. From Moscow, they pressed on across Siberia to Tokyo, establishing a new record time for the Britain to Japan route.

In July 1932, Johnson set a new solo record for a flight from London to Cape Town, South Africa, piloting the Puss Moth G-ACAB, named Desert Cloud. This achievement notably broke the record previously held by her new husband, Jim Mollison. Both the De Havilland Company and Castrol Oil prominently featured this flight in their advertising campaigns.

In 1934, the Mollisons participated in the England to Australia MacRobertson Air Race, flying a de Havilland DH.88 Comet named Black Magic. They set a record time for the flight from Britain to India during the race, leading until engine trouble forced them to retire at Allahabad.

On May 4, 1936, Johnson completed her final record-breaking flight, departing from Gravesend Airport and reclaiming her Britain to South Africa record in G-ADZO, a Percival Gull Six. In the same year, she was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Aero Club. She further developed her gliding skills, joining the Midland Gliding Club in Shropshire in October 1937, and remained an active flying member until gliding activities were suspended at the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1938, Johnson was involved in an incident where her glider overturned during a landing after a display at Walsall Aerodrome in England, but she sustained no serious injuries. Following this accident, she famously declared to reporters, "I still declare that gliding is the safest form of flying."

3.3. Marriage to Jim Mollison and Joint Flights

In 1932, Amy Johnson married fellow Scottish pilot Jim Mollison, who had proposed to her during a flight just eight hours after their initial meeting. Their marriage led to several joint aviation endeavors, including ambitious record attempts. In July 1933, Johnson and Mollison attempted a nonstop transatlantic flight from Pendine Sands, South Wales, aiming for Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York. They flew a de Havilland DH.84 Dragon I registered G-ACCV, which they named Seafarer. Their ultimate goal was to then fly Seafarer on to Baghdad to secure the record for the longest non-stop flight.

However, running low on fuel and flying in the dark, the couple decided to land short of New York. They spotted the lights of Bridgeport Municipal Airport (now Sikorsky Memorial Airport in Stratford, Connecticut) and circled it five times before crash-landing some distance outside the field in a drainage ditch. Both were ejected from the aircraft but fortunately sustained only cuts and gashes. After recovering from their injuries, the Mollisons were celebrated by New York society and were honored with a ticker tape parade down Wall Street.

3.4. Later Activities and Divorce

Amy Johnson and Jim Mollison divorced in 1937, after which she reverted to her maiden name. Following her divorce, Johnson began to explore diverse avenues for her livelihood, venturing into business, journalism, and fashion. She modeled clothes for the renowned designer Elsa Schiaparelli and even launched a travel bag under her own name. From 1935 to 1937, Johnson served as the President of the Women's Engineering Society, having previously been its vice-president since 1934. She succeeded Elizabeth M. Kennedy in this role and was later succeeded by Edith Mary Douglas. Johnson remained actively involved with the society until her death. In 1939, she found employment with the Portsmouth, Southsea and Isle of Wight Aviation Company, piloting short flights across The Solent and serving as a target for searchlight batteries and anti-aircraft gunners during practice drills.

4. Second World War Service

Amy Johnson's dedication to her country extended to her service during the Second World War, where she played a vital role in the Air Transport Auxiliary.

4.1. Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) Service

In March 1940, with the outbreak of the Second World War, the aircraft of the company employing Johnson were requisitioned by the Air Ministry. Consequently, Johnson, along with all other pilots in the company, received a notice of redundancy, as all aircraft were needed for the war effort. She was provided with a week's pay and an additional four weeks' pay totaling 40 GBP as a redundancy package.

Two months later, Johnson joined the newly established Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), an organization responsible for transporting Royal Air Force aircraft across the country. She quickly rose through the ranks, achieving the position of First Officer under the command of her friend and fellow pilot, Pauline Gower. Notably, her former husband, Jim Mollison, also flew for the ATA throughout the war. Johnson described a typical day in her ATA service in a humorous article that was posthumously published in 1941 in *The Woman Engineer* journal, offering a unique insight into her wartime contributions.

5. Death

Amy Johnson's life came to an abrupt and mysterious end during a wartime ferry flight, leading to enduring discussions and theories about the circumstances of her death.

5.1. Accident Circumstances and Final Flight

In her last known letter, written to her friend Caroline Haslett on New Year's Day 1941, Johnson expressed a hopeful yet poignant sentiment: "I hope the gods will watch over you this year, and I wish you the best of luck (the only useful thing not yet taxed!)". Just five days later, on January 5, 1941, Johnson was flying an Airspeed Oxford aircraft for the ATA, on a ferry flight from Prestwick via RAF Squires Gate to RAF Kidlington near Oxford. It is widely believed that she ran out of fuel while flying in severely adverse weather conditions.

Approximately five hours after her departure, a convoy of wartime vessels in the Thames Estuary observed a parachute descending, followed by the sighting of a person alive in the water, calling for help. Witnesses described the voice as female. The conditions at sea were extremely perilous: there was a heavy sea, a strong tide, falling snow, and intensely cold temperatures. Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher, the Captain of HMS Haslemere, bravely navigated his ship to attempt a rescue. The crew of the vessel threw ropes towards the person, but they were unable to reach them, and the individual was subsequently lost beneath the ship. Several witnesses reported seeing what they believed to be a second body in the water.

Fletcher, in a heroic act, dived into the frigid water and swam towards what was possibly a lump of yellow plywood. He rested on it for a few minutes before letting go. When a lifeboat finally reached him, he was unconscious. Tragically, he died in the hospital a few days later due to the severe cold. Amy Johnson's watertight flying bag, her log book, and her cheque book were later found washed ashore near the crash site. A memorial service for Johnson was held at the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields on January 14, 1941. Lieutenant Commander Walter Fletcher was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal in May 1941 for his valiant rescue attempt.

5.2. Disputed Causes of Death

The precise cause of Amy Johnson's death remains officially unknown and has been the subject of considerable speculation and controversy over the years. In 1999, reports emerged suggesting that her death might have been the result of friendly fire. Tom Mitchell, a resident of Crowborough, Sussex, claimed that he had shot down Johnson's aircraft. According to Mitchell, Johnson's plane twice failed to provide the correct identification code during the flight. He recounted how the aircraft was sighted and contacted by radio, but when a request for the signal was made, she gave the wrong one twice. Mitchell stated, "Sixteen rounds of shells were fired and the plane dived into the Thames Estuary. We all thought it was an enemy plane until the next day when we read the papers and discovered it was Amy. The officers told us never to tell anyone what happened."

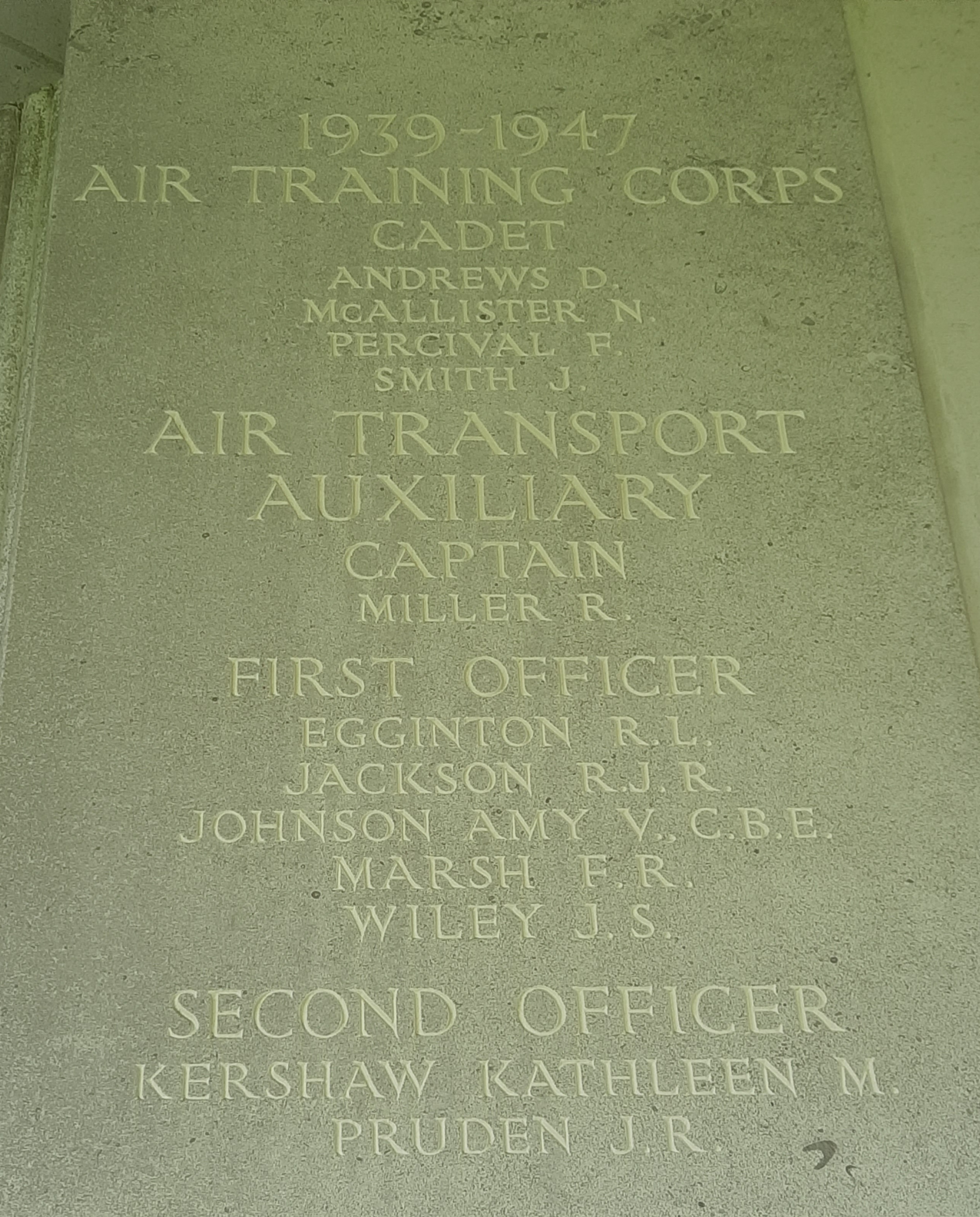

In 2016, historian Alec Gill put forth another theory, claiming that the son of a ship's crew member stated that Johnson had died because she was sucked into the blades of the ship's propellers. Although the crewman himself did not witness this event, he believed it to be true. As a member of the ATA, Amy Johnson has no known grave, and her body was never recovered. She is commemorated under the name of Amy V. Johnson by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission on the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede, alongside other personnel of the UK Air Transport Auxiliary who went missing and were presumed dead during the Second World War.

6. Honours, Tributes, and Impact

Amy Johnson's pioneering spirit and remarkable achievements have been recognized through numerous honours, memorials, and cultural depictions, leaving a lasting impact on aviation and inspiring future generations.

6.1. Awards and Commendations

For her groundbreaking achievements in aviation, Amy Johnson received several significant awards and official recognitions. She was awarded the prestigious Harmon Trophy and was appointed a Commander of the CBE in George V's 1930 Birthday Honours following her historic solo flight to Australia. Additionally, she was honored with the No. 1 civil pilot's licence under Australia's 1921 Air Navigation Regulations. In 1936, she was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Aero Club, further acknowledging her contributions to aviation.

6.2. Memorials and Places

Amy Johnson's legacy is preserved through various physical tributes across the United Kingdom and beyond. In June 1930, her flight to Australia inspired a popular song titled "Amy, Wonderful Amy", composed by Horatio Nicholls and recorded by several artists including Harry Bidgood, Jack Hylton, Arthur Lally, Arthur Rosebery, and Debroy Somers. In 1936, she was the guest of honour at the opening of the first Butlins holiday camp in Skegness.

A collection of Amy Johnson's souvenirs and mementos was donated by her father to Sewerby Hall in 1958, and the hall now features a dedicated room in its museum to her memory. In 1974, a statue of Amy Johnson by Harry Ibbetson was unveiled in Prospect Street, Hull, where a girls' school was also named after her (though the school closed in 2004). In 2016, to mark the 75th anniversary of her death, two new statues of Johnson were unveiled: one on September 17 at Herne Bay, near the site where she was last seen alive, and another on September 30, unveiled by Maureen Lipman near Hawthorne Avenue, Hull, close to Johnson's childhood home. The latter statue was listed by *The Guardian* in 2017 as one of the "best female statues in Britain".

Several plaques commemorate her: a blue plaque at Vernon Court, Hendon Way, in Childs Hill, London NW2; a green plaque on The Avenues, Kingston upon Hull; and another blue plaque in Princes Risborough, where she resided for a year.

Buildings and facilities named in her honour include:

- The "Amy Johnson Building", which houses the department of Automatic Control and Systems Engineering at the University of Sheffield.

- "Amy Johnson Primary School", located on Mollison Drive on the Roundshaw Estate, Wallington, Surrey, which is built on the former runway site of Croydon Airport.

- "The Hawthornes @ Amy Johnson" in Hull, a significant housing development by Keepmoat Homes on the site of the former Amy Johnson School.

- The "Amy Johnson Comet Restoration Centre" at Derby Airfield, where the Mollisons' DH.88 Comet Black Magic is undergoing restoration to flying condition.

- "Amy Johnson House" in Cherry Orchard Road, Croydon, a 20th-century building named for her, which was demolished in the mid-2010s.

- "Amy's Restaurant and Bar" at the Hilton hotels located at both London Gatwick and Stansted airports.

Other tributes to Johnson include a KLM McDonnell Douglas MD-11 aircraft named Amy Johnson, and after its retirement, a Norwegian Air UK Boeing 787-9 was named in her honour. "Amy Johnson Avenue" is a main road running northwards from Tiger Brennan Drive, Winnellie, to McMillans Road, Karama, in Darwin, Australia. "Amy Johnson Way" is a road connecting commercial premises in Blackpool, Lancashire, UK, adjacent to Blackpool Airport, and is also the name of a road in Clifton Moor, York. "Johnson Road" is one of the roads built on the site of the former Heston Aerodrome in west London.

In 2011, the Royal Aeronautical Society established the annual Amy Johnson Named Lecture to celebrate a century of women in flight and to honour Britain's most famous female aviator. Carolyn McCall, then Chief Executive of EasyJet, delivered the inaugural lecture on July 6, 2011, at the Society's headquarters in London. The lecture is held annually on or close to July 6 to commemorate the date in 1929 when Amy Johnson was awarded her pilot's licence. In February 2017, inmates of Hull Prison completed a full-size model of the Gipsy Moth aircraft used by Johnson for her solo flight to Australia, which was subsequently put on public display at Hull Paragon Interchange. In 2017, Google commemorated Johnson's 114th birthday with a Google Doodle. Also in 2017, the airline Norwegian painted a portrait of Johnson on the tail fin of two of its aircraft, recognizing her as one of the company's "British tail fin heroes", alongside figures like Queen singer Freddie Mercury and children's author Roald Dahl. A mural reading "QUEEN OF THE AIR" (a nickname given to Johnson by the British press) was painted in Cricklewood railway station to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of women obtaining the right to vote in the UK. In 2021, St Mary's Church in Beverley, East Yorkshire, announced plans to install a stone carving of Amy Johnson as part of a project celebrating women in the restoration of the medieval church's stonework. She will be featured alongside other notable women such as fellow engineer and Women's Engineering Society member Hilda Lyon, Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Seacole, Marie Curie, Rosalind Franklin, Helen Sharman, and Ada Lovelace.

6.3. Amy Johnson in Popular Culture

Amy Johnson's life and exploits have been widely depicted and celebrated across various forms of popular culture, though some portrayals have been more fictionalized than others. In 1942, a biographical film about Johnson's life, *They Flew Alone* (released in the US as *Wings and the Woman*), was produced and directed by Herbert Wilcox, starring Anna Neagle as Johnson and Robert Newton as Mollison.

In 1980, *Amy!* was released, an avant-garde documentary written and directed by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey and semiologist Peter Wollen. A 1984 BBC television film titled *Amy* featured Harriet Walter in the title role. In the 1991 Australian television miniseries *The Great Air Race*, also known as *Half a World Away*, which was based on the 1934 MacRobertson Air Race, Johnson was portrayed by Caroline Goodall. Johnson also received a passing mention in other works, such as the 2007 British film adaptation of Noel Streatfeild's 1936 novel *Ballet Shoes*, where the character Petrova is inspired by Johnson in her aspirations to become an aviator.

In radio, the 2002 BBC Radio broadcast *The Typist who Flew to Australia*, a play by Helen Cross, explored the theme that Johnson's aviation career was motivated by years of boredom in an unfulfilling secretarial job and a series of romantic adventures, including a seven-year affair with a Swiss businessman who ultimately married someone else.

Johnson's life also inspired several musical works. The song "Flying Sorcery" from Scottish singer-songwriter Al Stewart's album, *Year of the Cat* (1976), is a notable example. Other songs include *A Lone Girl Flier* and *Just Plain Johnnie* by Jack O'Hagan, sung by Bob Molyneux, and *Johnnie, Our Aeroplane Girl* sung by Jack Lumsdaine. *Queen of the Air* (2008) by Peter Aveyard is a musical tribute dedicated to Johnson. The indie pop band The Lucksmiths incorporated a clip of her Australia welcome speech as an introduction to their song "The Golden Age of Aviation."

More fictionalized portrayals include a *Doctor Who Magazine* comic story from 2013 titled "A Wing and a Prayer", in which the time-travelling Doctor encounters Johnson in 1930. The Doctor informs Clara Oswald that Johnson's death is a fixed point in time, leading Clara to realize that what matters is the appearance of her death. They proceed to save her from drowning and transport her to the planet Cornucopia. The character Worrals in the series of books by Captain W. E. Johns was modeled on Amy Johnson. In 2023, screenwriter Sally Wainwright, known for *Happy Valley*, expressed her interest in writing a drama about Johnson but stated that she "failed to convince" TV channels to greenlight the project.

6.4. Impact on Later Generations

Amy Johnson's life and career have had a profound and enduring influence, particularly as an inspiration for women in aviation and engineering. Her groundbreaking achievements, such as being the first woman to fly solo from London to Australia and her active participation in the Women's Engineering Society, served to challenge and break down gender barriers in fields historically dominated by men. She demonstrated that women were capable of extraordinary feats in technical and adventurous pursuits, inspiring countless individuals to pursue their dreams regardless of societal expectations. The numerous memorials, educational institutions, and cultural tributes in her name continue to highlight her legacy, encouraging new generations, especially young women, to enter aviation, engineering, and other STEM fields, ensuring her impact as a trailblazer remains relevant and celebrated.