1. Overview

Abu Nuwas, whose full name was Al-Ḥasan ibn Hānī 'Abd al-Awal al-Ṣabāḥ, Abū 'Alī (أَبُو عَلِي اَلْحَسَنْ بْنْ هَانِئْ بْنْ عَبْدِ اَلْأَوَّلْ بْنْ اَلصَّبَاحِ اَلْحُكْمِيِّ اَلْمِذْحَجِيAbū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan ibn Hānī ibn ʿAbd al-Awwal ibn al-Ṣabāḥ al-Ḥakamī al-MidḥajīArabic), also known as Abū Nuwās al-Salamī (أبو نواس السلميAbū Nuwās al-SalamīArabic), was a prominent classical Arabic poet who lived between approximately 747 and 816 AD. He is widely considered the foremost representative of the "muhdath" (modernist) poetry movement that emerged during the early Abbasid Caliphate. Of mixed Arab and Persian heritage, Abu Nuwas is celebrated for his bold and innovative poetic themes, particularly his vivid khamriyyat (wine poetry) and his candid love poetry, which often explored homoeroticism. His work was characterized by a satirical wit and a departure from traditional desert themes, focusing instead on urban life and pleasure. Abu Nuwas's enduring presence extends beyond literature into folklore, where he appears multiple times in One Thousand and One Nights as a witty companion to Harun al-Rashid and is widely recognized as a trickster figure in various cultural traditions.

2. Life and Background

Abu Nuwas's life and early career were shaped by his mixed heritage, his education in the intellectual centers of Iraq, and the influential figures who mentored him.

2.1. Birth and Family

Abu Nuwas was born in the province of Ahvaz (modern Iran) within the Abbasid Caliphate, either in the city of Ahvaz itself or one of its adjacent districts. His exact birth year is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 747 to 762 AD, though he is most commonly cited as being born between 756 and 758 AD. His father, Hani, was an Arab, likely from Damascus, who had served as a soldier in the army of Marwan II, the last Umayyad caliph. His mother, Gulban (also known as Gulnāz or Jullaban), was a Persian seamstress or weaver from Ahvaz. Hani had met Gulban while serving in the police force of Ahvaz. Abu Nuwas was only ten years old when his father died. Following his father's death, his mother took him to Basra in lower Iraq.

Abu Nuwas's full name was Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan b. Hāniʾ al-Ḥakamī (ابو علي الحسن بن هانئ الحكمي الدمشقيAbū ʿAlī al-Ḥasan ibn Hāniʾ al-Ḥakamī al-DimashqīArabic). The nisba "Hakami" is believed to derive from his paternal grandfather or great-grandfather, who served as a mawla (client) to Al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami, an Umayyad governor of Khorasan. The Banu Hakam were a South Arab (Yemeni) tribe. The origin of his popular name "Abu Nuwas" (meaning "father of the forelock" or "owner of the locks") has several theories: some suggest it refers to a mountain, others to his long, flowing hair, while a third theory posits he adopted it himself in emulation of Dhu Nuwas, the last king of the Himyarite Kingdom.

2.2. Education and Early Influences

Abu Nuwas received his formative education in the scholarly cities of Basra and Kufa. In Basra, he attended a Quran school at a young age and became a Hafiz, memorizing the entire Quran. His youthful appearance and charisma attracted the attention of Walibah ibn al-Hubab al-Asadi, a Kufan poet, who took Abu Nuwas to Kufa as an apprentice. Walibah recognized Abu Nuwas's poetic talent and encouraged him in this vocation. It is also believed that Walibah introduced Abu Nuwas to various pleasures and that their relationship may have been homoerotic, an experience that some scholars suggest mirrored Abu Nuwas's later relationships with adolescent boys.

After Walibah's death, Abu Nuwas became a disciple of the poet and translator Khalaf al-Ahmar. Khalaf al-Ahmar reportedly instructed Abu Nuwas to memorize thousands of lines of classical poetry and then, crucially, to forget them all before attempting to compose his own. This anecdote of "forced forgetting" is seen as symbolic of Abu Nuwas's poetic formation, emphasizing a break from rigid classical imitation. He also studied Arabic grammar under renowned grammarians such as Abu Ubaidah and Abu Zayd. To further refine and deepen his knowledge of Arabic literature and language, Abu Nuwas spent time among the Bedouin tribes in the desert.

3. Career in Baghdad

Abu Nuwas's professional life flourished in Baghdad, the newly established capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, where he gained patronage from the caliphs and developed his distinctive poetic style, which marked a significant departure from classical traditions.

3.1. Move to Baghdad and Court Life

After completing his education, Abu Nuwas moved to Baghdad with the intention of gaining favor with the caliphs through his poetry. Baghdad, at the time, was rapidly developing as the central hub of the vast Abbasid Empire. He successfully earned the patronage of the Abbasid caliphs Harun al-Rashid and his son, Al-Amin, becoming a celebrated court poet and a close companion, or nadim.

During this period, he befriended Aban al-Lahiqi, a court poet from the influential Barmakid family, which granted Abu Nuwas access to their circles. However, this connection may have been a strategic move by Al-Lahiqi to divert a potential rival from Harun al-Rashid's direct attention. When Harun al-Rashid purged the Barmakid family, Abu Nuwas briefly sought refuge in Egypt, where he composed panegyrics for the revenue chief who sheltered him. He soon returned to Baghdad and became a close confidant and drinking companion to the young Al-Amin, who later became caliph. Much of Abu Nuwas's poetry is believed to have been composed during Al-Amin's reign, from 809 to 813 AD. While they shared many adventures, Al-Amin also had Abu Nuwas imprisoned on occasion due to his excessive drinking.

3.2. Literary Style and Themes

Abu Nuwas is considered the foremost representative of the "muhdath" (modernist) movement in Arabic poetry. This movement, initiated by poets like Bashar ibn Burd in the early 8th century, sought to break away from the rigid structures and themes of classical qasida poetry. Abu Nuwas's contribution to this movement was profound; he focused on the vibrant urban life of Baghdad, its pleasures, and its social dynamics, rather than the traditional desert motifs.

His poetry was characterized by its witty and humorous tone, and an innovative use of language, often employing simpler vocabulary and freer forms compared to the classical style. A contemporary, Ismail bin Nubakht, remarked on Abu Nuwas's extensive learning despite his possessing very few books, noting that after his death, only a single quire of paper with rare expressions and grammatical observations was found in his house. Another contemporary, Abu Hatim Makki, praised Abu Nuwas for his ability to unearth deep meanings in his thoughts and express them eloquently. While his poetry was grammatically perfect and rooted in Arabic tradition, it was his bold departure from conventional themes that defined his unique style.

4. Major Works and Genres

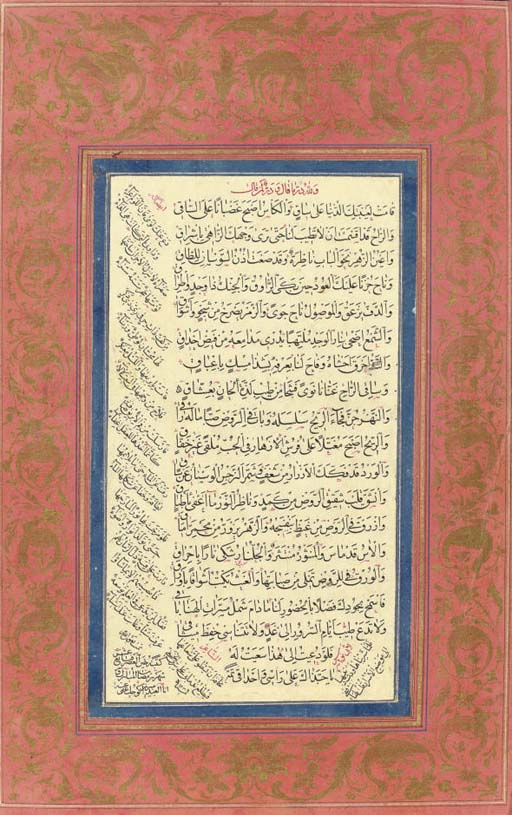

Abu Nuwas is renowned for his contributions across various poetic genres, often infusing them with innovative content and artistic merit that challenged the norms of his time. His collected works are known as his Diwan.

Abu Nuwas himself did not compile his Diwan, which led to the loss of many works, particularly those from his time in Egypt, and also resulted in numerous false attributions. However, many scholars dedicated themselves to editing his Diwan, including Abu Bakr al-Suli and Hamza al-Isfahani. Al-Suli's edition focused on poems believed to be genuinely by Abu Nuwas, while Al-Isfahani's compilation was more comprehensive, including both authentic and attributed works, alongside numerous anecdotes (akhbar) about the poet. Al-Isfahani's edition is significantly larger, containing approximately 1,500 works and 13,000 lines of poetry. Other early compilers and biographers included Yaḥyā ibn al-Faḍl, Ya'qūb ibn al-Sikkīt, Abū Sa'īd al-Sukkarī, Yūsuf ibn al-Dāyah, Abū Hiffān, Ibn al-Washshā' Abū Ṭayyib, Ibn 'Ammār (who also critiqued his work), and members of the Al-Munajjim family.

4.1. Khamriyyat (Wine Poetry)

Abu Nuwas was a pivotal figure in the development of khamriyyat, or wine poetry. This genre gained new prominence with the shift to the Abbasid dynasty, reflecting the spirit of a new age. His wine poems were likely composed to entertain the elite of Baghdad. The core of his khamriyyat lies in their vivid and exalted descriptions of wine: its taste, appearance, fragrance, and its effects on the body and mind.

He often incorporated philosophical ideas and imagery that glorified Persians and subtly mocked Arab classicism. For instance, in one of his khamriyyat, he describes wine being served in a silver jug adorned with Persian designs, featuring Chosroes on its base and hunting oryxes around its sides, emphasizing the prevalence of Persian imagery and language during this period. Abu Nuwas's wine poetry frequently carried both poetic and political undertones. Along with other Abbasid poets, he openly acknowledged his indulgence in wine and his disregard for religious prohibitions, often using wine as both an excuse and a symbol of liberation. A notable line from his khamriyyat contrasts the religious ban on wine with God's forgiveness, suggesting a facetious relationship with religious norms where his sins were justified within a religious framework. His poems celebrated the physical and metaphysical experience of drinking wine, defying traditional Islamic poetic conventions.

A recurring theme in Abbasid wine poetry, including Abu Nuwas's, was its association with pederasty, often because wine shops employed young boys as servers. His Diwan contains erotic sections where poems describe young servant girls dressed as boys drinking wine. Abu Nuwas explicitly explored the notion that homosexuality was introduced to Abbasid Iraq from the province where the Abbasid Revolution originated, stating that during the Umayyad Caliphate, poets exclusively focused on female lovers. His seductive poems often used wine as a central theme for blame and as a scapegoat. In his poem al-Muharramah, he describes being served by a Christian boy, glorifying the boy's beauty, and finding testimony in Christianity, using his literature to challenge religious and cultural norms by ridiculing heterosexual propriety, the condemnation of homosexuality, the alcohol ban, and Islam itself. Despite his many poems about affection for boys, he also famously related the taste and pleasure of wine to women. His preference for boys was not uncommon among men of his time, as homoerotic lyrics and poetry were popular among Muslim mystics.

4.2. Love Poetry

Abu Nuwas's poetry extensively explored themes of love and desire, including mujūniyyāt (poems about boys) and mudhakkarat (poems about male beauty). His erotic lyric poetry, predominantly homoerotic, comprises over 500 poems and fragments. These works delve into sensuality, homoeroticism, and social commentary, reflecting his personal life and challenging societal norms.

His affection for young boys was openly expressed in his verses and social conduct. He used his writing to critique conventional heterosexual propriety and the societal condemnation of homosexuality. While many of his poems detailed his love for boys, he also employed a distinctive technique of comparing the pleasure and taste of wine to women. His love poems often contain themes of sex, eroticism, power, and self-control, depicting lavish parties in desert bars filled with honeyed drinks, delicacies, and wine, surrounded by compliant lovers and fellow revelers.

4.3. Satirical Poetry and Other Genres

Abu Nuwas was a master of various poetic forms beyond wine and love poetry. He actively participated in the established Arabic tradition of satirical poetry, known as hijā, which often involved vicious poetic exchanges and insults between rival poets. He was acutely aware of his talent for satire.

He is also credited with inventing or perfecting the tardiyya, or hunting poem, elevating it to a distinct genre. While hunting themes existed in pre-Islamic poetry, Abu Nuwas's contributions solidified its status. His works also included panegyrics (madīḥ), poems of praise dedicated to figures of power, and poems of penitence, which he composed later in his life. His poetry also touched upon themes of freedom, as well as anxieties about death and aging.

4.4. Literary Innovations

Abu Nuwas made significant contributions to Arabic poetry, marking him as a key figure in the "muhdath" (modernist) movement. He is widely credited with inventing or perfecting the literary form of the mu'ammā, a type of riddle solved by combining the constituent letters of a hidden word or name. He also perfected the genres of khamriyya (wine poetry) and tardiyya (hunting poetry).

His work represented a conscious break from classical Arabic poetic traditions, particularly the rigid structure of the qasida. While classical qasidas typically began with lamentations over abandoned campsites, Abu Nuwas famously declared he would begin by asking for the nearest tavern. This playful defiance highlighted his rejection of outdated themes and his embrace of urban, contemporary subjects. He skillfully drew from older poetic forms while simultaneously severing ties with their conventional applications. His ability to use a free-flowing rhetoric to describe characters and scenes is considered a hallmark of the "muhdath" and early "badi'" styles.

His artistic output was influenced by two contrasting factors: the normative value of classical poetry established by grammarians and scholars, which influenced how poetry was appreciated, and the social function of poets, whose status often depended on patronage. This dual influence meant that while his panegyrics largely adhered to classical forms and vocabulary, his more innovative poems, such as those on wine and love, allowed for greater artistic freedom and reflected the changing times.

5. Thought and Beliefs

Abu Nuwas's poetry is a rich tapestry of philosophical, social, and cultural commentary, offering insights into his personal views and the broader context of the Abbasid era.

5.1. Poetic Themes and Philosophy

At the core of Abu Nuwas's poetry lies a strong current of hedonism, reflecting his personal inclination towards a life of revelry and indulgence in parties and drink. He was known for his heavy drinking, a theme frequently explored in his early works, which often celebrated wine, women, and love.

Beyond hedonism, his poetry engaged in a subtle yet potent critique of religious norms. He composed satirical verses that challenged Islam, often using wine as a means of both excuse and liberation. For example, he provocatively compared the religious prohibition of wine to God's capacity for forgiveness. In his poem al-Muharramah, he depicts being served by a Christian, glorifying the beauty of a young boy, and even suggesting a leaning towards Christianity, using these elements to ridicule heterosexual propriety, the condemnation of homosexuality, and the alcohol ban, effectively testifying against the prevailing religious and cultural norms of the Abbasid Caliphate.

However, a significant shift occurred in his later life, particularly after a period of imprisonment. His poetry transformed, becoming deeply religious and expressing profound repentance and submission to God's power. These later verses on repentance are seen as an articulation of his heightened religious sentiment, as exemplified by his poem "Forgiveness." Alongside these themes, his works also reflected on more universal aspects of human existence, such as the anxiety of death and the inevitability of aging.

5.2. Cultural Commentary

Abu Nuwas's works serve as a valuable mirror reflecting Abbasid society, particularly the lifestyle and values of the Baghdad elite. He intentionally incorporated Persian cultural elements and imagery into his poetry, a significant aspect given his mixed heritage and the strong Persian influence in the Abbasid court. This inclusion often went hand-in-hand with his critique of Arab classicism, which he viewed as outdated and overly focused on desert traditions.

His poetry offered a sharp commentary on religious norms and social conventions. He openly challenged the prevailing moral and religious standards, particularly regarding alcohol consumption and sexuality. His critical thought was frequently directed towards religious institutions, as he used his verses to express defiance against what he perceived as restrictive or hypocritical societal expectations. His embrace of urban themes and his rejection of traditional Bedouin motifs further underscored his role as a commentator on the evolving cultural landscape of the Abbasid era.

6. Imprisonment and Death

Abu Nuwas's life included periods of confinement, often due to the controversial nature of his poetry and lifestyle. The circumstances of his death are subject to differing accounts.

6.1. Imprisonment Experience

Abu Nuwas's frequent indulgence in drunken exploits and his controversial poetic content often led to his arrest and confinement. He was imprisoned during the reign of Caliph Al-Amin, shortly before his death. One notable incident involved a poem he composed that satirized the Caliph, which reportedly angered Al-Amin and led to Abu Nuwas's incarceration. This period of imprisonment is often cited as a turning point in his life, after which his poetry shifted from hedonistic themes to more religious and penitent verses.

Accounts also suggest an incident involving the Nawbakht family. It is believed that he was either poisoned by them after being framed with a satirical poem, or severely beaten by them for a satire falsely attributed to him. These incidents highlight the volatile nature of his life and the risks associated with his provocative artistic expression.

6.2. Death and Burial

Abu Nuwas died during the Great Abbasid Civil War, specifically before Al-Ma'mun's advance from Khurāsān. His death year is uncertain, with various sources providing conflicting dates: some suggest 806 AD, others 813 AD, and some state 814 AD. The most commonly cited period for his death is between 814 and 816 AD.

The cause of his death is also highly disputed, with four main accounts surviving:

- He was poisoned by the Nawbakht family, allegedly framed by a satirical poem.

- He died in a tavern, drinking until his final moments.

- He was beaten by the Nawbakht family for a satire falsely attributed to him, with wine playing a role in the heightened emotions of his last hours. This account appears to combine elements of the first two.

- He died in prison. However, this version contradicts numerous anecdotes stating that he suffered from illness and was visited by friends in his final days, implying he was not in prison.

The most probable scenario suggests he died of ill health, possibly while residing in the house of the Nawbakht family, which may have given rise to the myth of his poisoning. Abu Nuwas was buried in the Shunizi cemetery in Baghdad.

7. Legacy and Influence

Abu Nuwas's impact extends far beyond his lifetime, shaping literary traditions, influencing subsequent poets, and permeating popular culture and folklore across various regions.

7.1. Literary Influence

Abu Nuwas is considered one of the greatest poets in classical Arabic literature, and his influence on subsequent generations of writers was profound. He is noted for influencing Persian poets such as Omar Khayyam and Hafiz. Ibn Quzman, a 12th-century poet writing in Al-Andalus, greatly admired Abu Nuwas and has often been compared to him.

His collected poetry, the Diwan Abu Nuwas, has been compiled and printed in numerous editions and languages over centuries. The earliest anthologies and biographies of his work were produced by scholars such as Yaḥyā ibn al-Faḍl, Ya'qūb ibn al-Sikkīt, Abū Sa'īd al-Sukkarī, Abū Bakr ibn Yaḥyā aI-Ṣūlī, Ḥamza ibn al-Ḥasan al-Iṣfahānī, Yūsuf ibn al-Dāyah, Abū Hiffān, Ibn al-Washshā' Abū Ṭayyib, Ibn 'Ammār (who also critiqued his work), and members of the Al-Munajjim family. Notably, Ibn 'Ammār wrote a critique of Abu Nuwas's work, even citing instances of alleged plagiarism.

7.2. Cultural Presence and Folklore

Abu Nuwas's character has transcended his historical existence, becoming a prominent figure in folklore. He appears multiple times in One Thousand and One Nights as a witty and often roguish companion to Caliph Harun al-Rashid, sometimes portrayed as a jester or a humorous sidekick who embarks on adventures with the caliph.

His stories have spread widely, particularly in East Africa and Indonesia. In Swahili culture in East Africa, he is known as Abunuwasi or Kibunuwasi and is a popular trickster figure, sometimes even anthropomorphized as a hare. This transmission of his character into Swahili folklore was facilitated by historical trade links and the integration of Islamic tales into local oral traditions during the colonial era. Similarly, in Indonesia, Abu Nuwas is known as Abunawas and features in various folk stories, often highlighting interactions between ordinary people and the upper classes. He is sometimes mistakenly conflated with the satirical Sufi figure Nasreddin Hoja, though they were distinct individuals living in different eras.

Abu Nuwas has also been fictionalized in modern literature and media. He is the protagonist in Andrew Killeen's novels The Father of Locks (2009) and The Khalifah's Mirror (2012), where he is depicted as a spy working for Ja'far al-Barmaki. His love poetry is extensively quoted by a protagonist in Tayeb Salih's Sudanese novel Season of Migration to the North (1966) as a means of seduction. The Tanzanian artist Godfrey Mwampembwa (Gado) created a Swahili comic book titled Abunuwasi in 1996, drawing inspiration from both East African folklore and the fictional Abu Nuwas of One Thousand and One Nights. Furthermore, Pier Paolo Pasolini's 1974 film Arabian Nights adapted the "Sium" story based on Abu Nuwas's erotic poetry, incorporating his original verses into the scene.

7.3. Commemoration and Modern Reception

Abu Nuwas is commemorated in various ways, reflecting his lasting cultural significance. The city of Baghdad has several places named in his honor, including Abu Nuwas Street, which runs along the east bank of the Tigris River in a historically prominent neighborhood, and Abu Nuwas Park, a 1.6 mile (2.5 km) stretch between the Jumhouriya Bridge and the 14th of July Bridge in the Karada district. In 1976, a crater on the planet Mercury was named in honor of Abu Nuwas.

Despite his historical prominence, Abu Nuwas's works have faced censorship in modern times, particularly due to their explicit homoerotic content. While his writings circulated freely until the early 20th century, the first modern censored edition of his works was published in Cairo in 1932. In January 2001, the Egyptian Ministry of Culture ordered the burning of approximately 6,000 copies of his homoerotic poetry. Similarly, the Saudi Global Arabic Encyclopedia entry for Abu Nuwas omitted all mentions of pederasty. In contrast, the Abu Nawas Association, founded in Algeria in 2007, was named after the poet with the primary aim of decriminalizing homosexuality in Algeria, seeking the abolition of penal code articles that criminalize it. This highlights a contemporary re-evaluation and re-interpretation of his poetry and legacy in the context of human rights and social progress.